70

Palliative and end-of-life care

The aim of palliative care is to provide comfort to the baby who is dying or has a life-limiting condition and holistic support for the family. Extreme prematurity, congenital malformations, neonatal encephalopathy and infection account for most neonatal deaths. The decision to offer palliative care may be made antenatally, soon after delivery or later during neonatal care. It should involve the multidisciplinary team caring for the baby, together with the family. National guidelines on end-of-life care are available (see Chapter 68). Discussions should be led by the senior clinician in a private and quiet environment. Parents should be offered the chance to involve extended family or friends. These decisions are difficult and parents must be given time to consider the issues. Involving religious or cultural representatives or a second opinion from an independent clinician may be helpful.

Care Plans

When it becomes clear that the baby is unlikely to survive and treatment aimed at prolonging life is no longer appropriate, a care plan focusing on palliative care should be developed to ensure that the baby dies free of pain or discomfort and with dignity. Pediatric palliative care services may assist.

Regular assessment of comfort, pain and physiological status should be undertaken. Physical care, including positioning, mouth care and skin-to-skin contact, should be offered. Analgesia should not be reduced for fear that it might hasten death; it may need to be increased for pain or distress. Other forms of treatment, such as antibiotics, oxygen, anticonvulsants and antireflux medication, may be required for symptom control. Electronic monitoring is not usually recommended.

The aim of feeding in palliative care is to provide comfort and reduce hunger, not to achieve growth. A baby who can feed orally should do so. Breast-feeding may be comforting even when non-nutritive. Gavage (nasogastric) feeding may be appropriate for a baby who cannot feed orally but shows signs of hunger. Parenteral nutrition is rarely indicated.

Place of care

When death is expected, the baby should be cared for in a private area with the family. This may be in the hospital, their home or a hospice, depending on preference, available support and how long the baby is expected to live. If mechanical ventilation is withdrawn, extremely preterm infants usually die shortly afterwards, but mature infants may live for a considerable period. Parents need to be forewarned, and the place of care may change if the baby survives longer than expected. If parents are taking their baby home for end-of-life care, appropriate support must be in place, including medications not only for current but also potential symptoms, information about who to contact for routine and emergency problems, and what to do after the infant has died.

Support for the parents, siblings and family

The needs of each member of the baby’s family should be considered, including parents, siblings, grandparents and extended family. It is now uncommon for people to have experience of death or to have seen a dead person, and many have fears about what will happen around the time of death. This needs to be discussed.

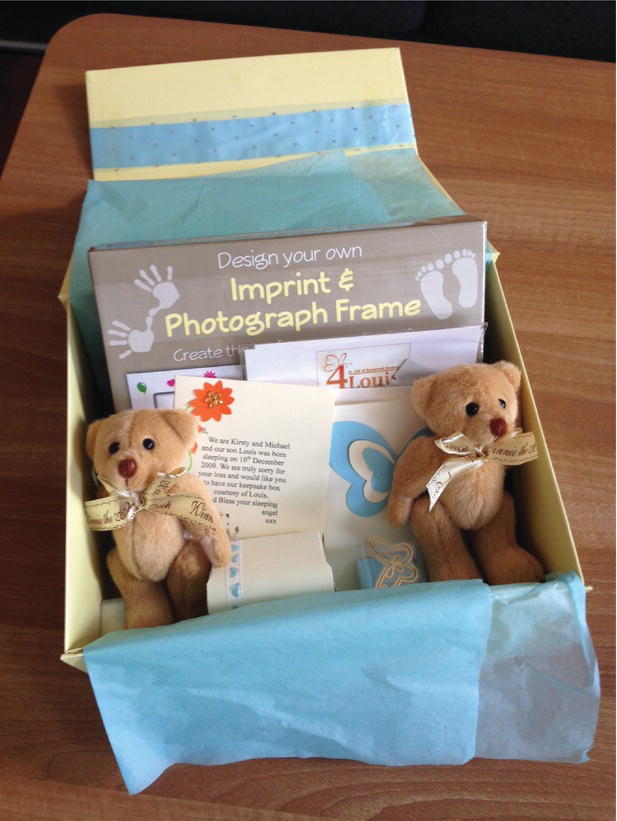

The family should be given the opportunity to create and collect mementoes before the baby dies and siblings can help with this. For example, a ‘journey’ or ‘memory’ box can be provided (Fig. 70.1). Mementoes might include antenatal scan pictures, photographs, foot and hand prints, a lock of hair and name tags. Religious ceremonies including blessings and baptisms should be supported.

Fig. 70.1 Memory boxes can be used to collect mementoes of the baby’s life.

Care after death

Parents should be encouraged to hold the baby before death and afterwards, if they want to. They may wish to bathe and dress their baby. Give unhurried, sympathetic care of the body after death, and provide unrestricted access for family. Cultural and religious rituals should be respected. Many parents value photographs of them and their baby at this time, especially if this is the first occasion they have held their baby without tubes, lines and monitors. ‘Cold cots’ can extend the amount of time available for the family to be with their baby after death (Fig. 70.2). Some families may wish to take the baby home and this should be facilitated. Information about registering the death and funeral arrangements should be provided. Inform the family practitioner or pediatrician, health visitor, obstetrician and other professionals involved that the baby has died. Some units have remembrance books and hold memorial services.

Fig. 70.2 Cold mattresses can be used with traditional cribs (cots) to prolong the time that family can spend with the baby after death.

Grief is a normal response to an infant’s death. Parents and staff need to know that it is normal to show emotion and be given the opportunity to express their feelings. Grief may include shock, denial, anger, sadness or relief. There may be physical symptoms of anxiety, depression, tearfulness, loss of appetite, fatigue, insomnia and inability to concentrate. Grief may last years but is highly individual; in many it is most intense in the first few months. Parents may need advice about supporting siblings and other family members. Each parent may have a different pattern of grief and this may place stress on their relationship. Provide information about professional resources and self-help groups for bereavement support and counseling.

Families often find it helpful to have ongoing communication with the health-care team. A meeting arranged a few weeks after the child has died provides an opportunity to discuss the circumstances and to answer any questions and address any unresolved issues. It may be helpful if the obstetrician is also present. Health-care providers must be good listeners, in order to learn how the family is feeling. If there are concerns about abnormal grieving, professional assessment and support are recommended.

Caring for staff

The death of a baby may be distressing for staff, especially after protracted periods of intensive care, during which staff and parents become closely involved. The infant’s death may be perceived as a failure. Open discussion between all members of staff is crucial, so that all are fully informed and are able to express their feelings and concerns. Dialogue is especially important when withdrawal of life support is being considered. Many units provide personal psychological support for staff.

Organ donation

Donation of a baby’s tissue or organs may provide hope to families in an otherwise hopeless situation. Until recently, neonatal whole organ transplant was not widely available in the UK as guidelines on the diagnosis of death by neurological criteria in neonataes had not been published. However, donation of tissues or organs from neonates after circulatory death has sometimes been possible. This includes, but is not limited to heart valves. The US does have published criteria for the determination of brain death in term infants, and also protocols for donation. This has allowed transplantation of a number of organs, including heart, lung, kidney, liver and small bowel.

Autopsy

Why is it performed?

An autopsy should be offered, even if the cause of death is thought to be known. Advanced imaging and genetic tests mean that clinicians and families sometimes feel that autopsies are unnecessary and the autopsy rate has fallen markedly in the US and UK in the past 20 years. However, autopsy findings differ from the clinical diagnosis in 10 − 32%. Autopsy can be a legal requirement, e.g. after a sudden unexpected death or recent surgery, or if unnatural causes are implicated. Usually, it is performed to:

- help parents understand why their baby died,

- aid genetic counseling and planning future pregnancies

- help clinicians audit their management

- confirm the diagnosis or identify diagnoses that were missed.

- contribute to medical education and research. It should be performed by a pediatric pathologist.

What is involved in an autopsy?

Imaging:

- Photographs (particularly helpful for dysmorphology).

- X-rays (and MRI if indicated) for skeletal and other pathology not evident on clinical examination.

External and internal examination:

- Involves a full-length incision, which should be invisible when clothed.

- All organs are removed, inspected and weighed. Samples are taken for microbiological and histological analysis.

Organ retention:

- Some organs may need to be retained temporarily for fixing, mainly the brain and heart.

- For teaching or research. This requires explicit consent.

Consent

Detailed consent must be obtained unless the autopsy is legally required. All procedures must be described, and agreement reached about retention and disposal of tissues in a lawful and respectful way, or whether tissues should be returned for burial. Even if autopsy is legally required, parents should be informed about the procedure.

Are there alternatives to autopsy?

Post-mortem MRI, focused autopsy or specific tissue biopsy may be performed, but may miss diagnoses such as infection and metabolic disorders; conventional autopsy remains the gold standard.