72

Follow-up of high-risk infants

Goals

The goals of high-risk follow-up are:

- early identification of disability or developmental or behavior problems

- management of ongoing medical issues

- facilitation of early intervention, with referral if necessary

- family support

- monitoring of neonatal outcomes.

Criteria

High-risk infants include:

- very preterm (usually <1500 g or <32 weeks of gestation)

- neurologic abnormality, including:

- – neonatal seizures

- – hypoxic−ischemic encephalopathy

- – neonatal meningitis

- mechanical ventilation/nitric oxide therapy/ECMO

- severe IUGR (intrauterine growth restriction)

- congenital malformations (significant)

- maternal drug misuse

- significant parental psychosocial problems.

Organization and timing

Timing of visits will vary with different programs and with the extent of pediatric neurodevelopmental expertise available to the family locally. It will also depend on whether neurodevelopmental outcome is being monitored at standard times. A typical program for clinic visits and reason for their timing is shown in Fig. 72.1.

Fig. 72.1 An example of a high-risk follow-up program.

Who should conduct neonatal follow-up?

Many neonatologists provide neonatal follow-up with or without support from other physicians. This has the advantage of continuity of care for the parents. It also gives direct feedback on the sequelae of neonatal care but demands out-of-service referral if specialist help is required.

Good follow-up programs are multidisciplinary and include:

- developmental specialists − particularly for older children, when developmental assessment and management become more specialized and complex; in some programs all follow-up is performed by developmental specialists

- community nursing team − if involved with the family

- dietitian

- therapists

- psychologist

- social services.

The family practitioner/pediatrician provides general pediatric care and other pediatric specialists may be required for specific problems such as pulmonary or ophthalmology.

Components

- Growth monitoring.

- Neurologic and developmental assessment, including behavior.

- Vision and hearing.

- Social/family integration.Monitor chronic health conditions.School performance.

Outcome measures

Evaluation is tailored to the child’s age. Most follow-up programs conduct formal data collection at 18−24 months of age corrected for prematurity, including a disability assessment, neurologic evaluation and a developmental assessment using a standardized assessment (see Chapter 38).

Widely used developmental assessments at this age are the Bayley Scales or the Griffiths Scales (Table 72.1). They are standardized to a population mean of 100 with a standard deviation of 15 points. Children with scores <55 (−3 standard deviations) have severe developmental impairment likely to persist, children with scores 55−70 have moderate impairment and are highly likely to have low scores at later ages, while children with scores 70−85 have milder impairment and may catch up.

Table 72.1 Widely used developmental assessments.

| Bayley Scales of Infant Development (3rd edition) | Griffiths Mental Development Scales − Revised |

| Age range: 0–42 months | Age range: 0–24 months (Baby scales) 24–96 months (Extended) |

Subscales:

|

Subscales:

|

A formal classification of disability at 2 years is shown in Table 38.1. Such definitions are useful for comparing outcomes between centers and for evaluating the results of trials.

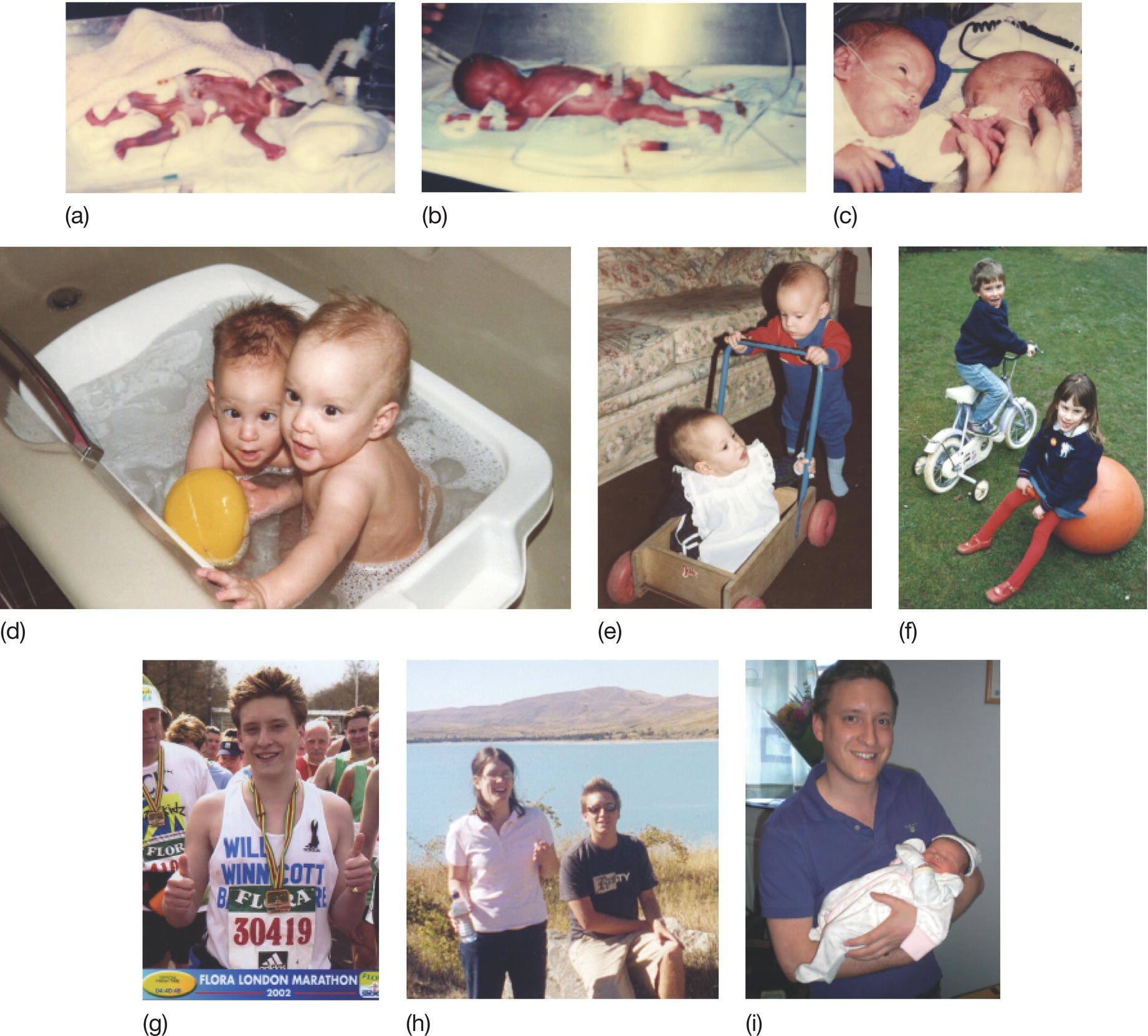

Follow up of older children (Fig. 72.2) is outside the remit of most neonatal follow-up programs because it requires formal IQ and behavioral screening. School evaluation by the class teacher is valuable for identifying need for support.

Fig. 72.2 Tiny preterm babies do grow up! Sally and William, from birth at 26 weeks to adulthood. (a) Sally at a few hours in intensive care. (b) William shortly after extubation. (c) Together at last at 4 weeks! (d) At a year. (e) Just walking. (f) At 5 years. (g) At 18 years, William completing the London marathon. (h) At 19 years, Sally and William on vacation in New Zealand. (i) The next generation has arrived, rather larger at birth than her father! (With thanks to Sally and William for permitting the use of these photographs.)