In my youth, Leonardo da Vinci seemed the greatest genius of all time. An extraordinary inventor of every sort of machine, a magnificent sculptor, one of the world’s greatest painters, and the finest illustrator and draftsman who ever lived. When our daughters were young, Marcella and I made a point of taking them to as many exhibitions of Leonardo’s work as we could—in London, Paris, Rome, Milan, Le Clos Lucé, and Amboise.

Then, as my knowledge of Chinese inventions slowly expanded, particularly with information provided by friends of our website, I began to wonder. More and more of Leonardo’s inventions appear to have been invented previously by the Chinese. I began to question whether there might be a connection—did Leonardo learn from the Chinese? The 1421 team and I examined the subject for years but came to no conclusions.

Leonardo drew all the essential components of machines with extraordinary clarity—showing how toothed wheels, gear wheels, and pinions were used in mills, lifting machines, and machine tools. He described how and why teeth could transfer power, the efficacy of antifriction teeth, the transmission of power from one plane to another, and continuous rotary motion. He drew and described ratchets, pins, axles, cams, and camshafts. Pulleys were an integral part of many of his mechanisms; he produced different systems and applications for them.

Some of the earliest known examples of gear wheels in China have been dated to ca. 50 B.C.

A toothed gear wheel, as drawn by Leonardo in the Madrid Codices.

All these devices had been used in China for a very long time. In the Tso Chuan are illustrations of bronze ratchets and gear wheels from as early as 200 B.C. that have been discovered in China.

Axles from the third and fourth centuries B.C. have been excavated from the royal tombs at Hui Hsien. By the second century B.C., in the Han dynasty, complex forms of cam-shaped rocking levers for the triggers of crossbows were in use. The Hsun I Hsiang Fa Yao, written in about A.D. 1090, illustrates a chain drive. By the eleventh century A.D. flywheels were used in China for grinding. The earliest archaeological evidence of a pulley is a draw well representing a pulley system of the Han dynasty.

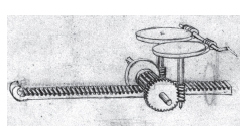

One of Leonardo’s best-known inventions was the paddle-wheel boat. The paddle-wheel mechanism was fundamental to China’s early naval supremacy. The sight of a boat traveling forward at great speed seemingly without oars or sails was terrifying to those in its path. The first record of the existence of paddle-wheel boats occurs in a Chinese account of a naval action under the command of Wang Chen-o, an admiral of the Liu Sung dynasty in A.D. 418.1 “These vessels later reached enormous proportions: one monster from the Southern Sung dynasty was said to have been 300 feet long. It was crewed by 1000 men and powered by thirty-two paddle wheels.”2

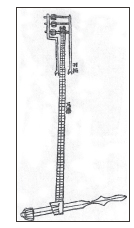

The oldest known illustration of an endless power-transmitting chain drive from Su Sung’s Hsun I Hsiang Fa Yaoch drawn in A.D. 1090.

Leonardo da Vinci’s illustration of a chain drive (Madrid Codices).

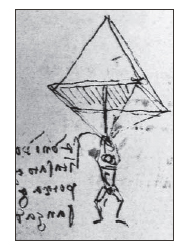

Leonardo is renowned for his drawings of different forms of manned flight, notably his helicopter and parachutes and his attempts at wings. By Leonardo’s day, the kite had been in use for hundreds of years. “China is the homeland of the kite…the oldest heavier-than-air craft that gains lift from the wind. It is believed that the kite was invented some 3000 years ago by Lu Ban…c.507–444 bc a Chinese master carpenter of the Lu State in the Spring and Autumn period. It was said that Lu Ban made a magpie out of bamboo pieces, which could fly. The master carpenter was also the first to use the kite in military reconnaissance.”3

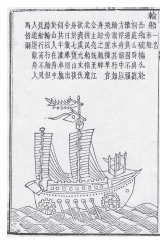

Drawing of a Sung paddle-wheel warship.

Along with the other Renaissance engineers Leonardo penned his own version of the paddleboat.

Parachutes were in use in China fifteen hundred years before Leonardo.

According to the historical records by Sima Qian of the Western Han dynasty, Shun, a legendary monarch in ancient China was deeply hated by his father, a blind old man. When Shun was working on top of a high granary, his father set fire to the granary from below, intending to kill Shun. Holding two cone-shaped bamboo hats in his hands, Shun flew down and landed safely. This book also describes how more recently (in 1214) a thief managed to steal the leg of a statue from the top of a mosque. When caught he admitted to using two umbrellas as a parachute to save himself from injury on his descent.4

The parachute is a small detail on a folio of the largest collection of da Vinci’s notebooks, the Codex Atlanticus.

Hot-air balloons were known in the second century A.D. in China. The contents of an egg were removed from the shell, then a little mug-wort tinder was ignited inside the hole so as to cause a strong air current. The egg rose up in the air and flew away.”5

The Chinese had made use of the essential principle of the helicopter rotor from the fourth century A.D., a fact noted by the philosopher and alchemist Ko Hung. By then, helicopter toys, like whirligigs, were popular in China, a common name being “bamboo dragonfly.” The toy was a bamboo with a cord wound around it and with blades sticking out from the bamboo at an angle. When the cord was pulled, the bamboo and blades rotated and the toy ascended as the air was pushed downwards. Needham describes a number of examples of rotating blades being used for flight, often in the form of flying cars.6

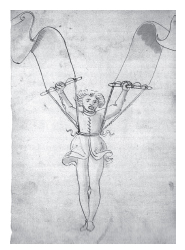

Leonardo devoted much time to the possibilities of manned flight. The earliest Chinese description of the concept occurred in the accounts of the short-lived and obscure Northern Chi dynasty (ninth century B.C.), when the emperor Kao Yang “caused many prisoners condemned to death to be brought forward, had them harnessed with great bamboo mats as wings, and ordered them to fly to the ground from the top of the tower…. All the prisoners died but the emperor contemplated the spectacle with enjoyment and much laughter.”7

A pictorial version of the aerial car, from the Shan Hai Ching Kuang Chu. “The skill of the Chi-Kung people is truly marvellous; by studying the winds they created and built flying wheels, with which they can ride along the paths of the whirlwinds….” “The artist here has drawn the aerial car with two wheels, but both seem to be intended to represent screw-bladed rotors….” (Text of the-2nd century, or earlier, plus 17th-century commentary).

A later description comes from Marco Polo in the Z manuscript.

And so we will tell you how when any ship must go on a voyage, they prove whether her business will go well or ill. The men of the ship will have a bundle or a grating of willow stem and at each corner and side of this framework will be tied a cord and they will all be tied at the end of a long rope. Next they will find some fool or drunkard and will bind him on the hurdle, since no-one in his right mind or with his wits about him would expose himself to that peril. And this is done when a strong wind prevails. Then the framework being set up opposite the wind, the wind lifts it and carries it up into the sky, while the men hold on by the long rope. And, if while this is in the air, the hurdle leans towards the way of the wind, they pull the rope to them a little so that it is set again upright, after which they let out some more rope and it rises higher. And if again it tips, once more they pull on the rope until the frame is upright and climbing, and then they yield rope again, so that in this manner it would rise so high that it could not be seen, if only the rope were long enough. The augury they interpret thus: if the hurdle going straight up makes for the sky they say the ship for which the test has been made will have a quick and prosperous voyage…. But if the hurdle has not been able to go up, no merchant will be willing to enter the ship.8

The idea of a man using wings for flight existed in Chinese legend hundreds of years before this fifteenth century Sienese flying man.

One of the many weapons mastered by China before Europe was the cannon.

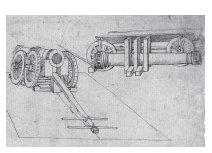

The dismountable cannon appears in da Vinci’s notebook and in those of many other Renaissance engineers.

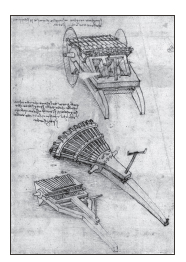

Leonardo drew an array of gunpowder weapons, including three variations of the machine gun, which can be seen in the fire lances used in China since A.D. 950.

The Genius of China states:

Fire lances with several barrels were frequently used and they were built so that when one fire-tube had exhausted itself, a fuse ignited the next, and so on. One triple barrelled fire lance was called the “triple resister” and another was called “the three eyed lance of the beginning of the dynasty…” One curious weapon was the “thunder fire whip” a fire lance in the shape of a sword, three feet two inches long tapering into a muzzle. It discharged three lead balls the size of coins…. There were also huge batteries of fire lances which could be fired simultaneously from mobile racks…a great frame with several wheels would hold many layers of sixteen fire lances one after the other…. When the enemy approaches the gate, all the weapons are fired in a single moment, giving the noise like a great peal of thunder, so that his men and horses are all blown to pieces. You can then open the city gates and relaxing, talk and laugh as if nothing had happened; this is the very best device for the guarding of cities.9

Leonardo’s multibarreled machine gun was essentially a reworking of a concept that had been used by the Chinese for centuries beforehand.

Leonardo also drew different types of cannons, mortars, and bombards. The Chinese use of bombards is well catalogued throughout the ages.10

Leonardo designed many different types of bridges, including suspension bridges. The first mention of a suspension bridge with cables and planking appears in 25 B.C. “Travellers go step by step here, clasping each other for safety and rope suspension bridges are stretched across the chasms from side to side.”11

By the seventh century China had segmental arch bridges. The Ponte Vecchio in Florence is a copy of a bridge in Quanzhou.

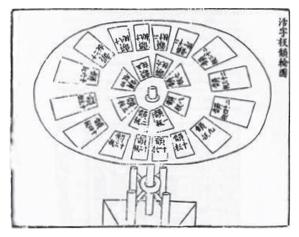

Leonardo was extremely curious about printing. He was eager to reproduce his drawings faithfully while saving time and labor through increased automation. The printing press by his time was in use all over China. Moveable type, however, was a relatively recent development; we shall return to this in later chapters.

Comparisons of the machines of Leonardo with earlier machines from China reveal close similarities in toothed wheels and gear wheels, ratchets, pins, and axles, cams and cam-shaped rocking levers, flywheels, crankshaft systems, balls and chains, spoke wheels, well pulleys, chain devices, suspension bridges, segmented arch bridges, contour maps, parachutes, hot-air balloons, “helicopters,” multibarreled machine guns, dismountable cannons, armored cars, catapults, barrage cannons and bombards, paddle-wheel boats, swing bridges, printing presses, odometers, compasses and dividers, canals and locks.

Even the most devoted supporter of Leonardo (like my family and I!) must surely wonder whether his work’s amazing similarity to Chinese engineering could be the product of coincidence.

A revolving-type table printing press found in the Nung Shu, 1313. The Nung Shu was printed using a similar device.

Was there any connection between the Chinese visit of 1434 and Leonardo’s designs sixty years later? For many years I searched for clues in Leonardo’s life but could find none. He was extraordinarily observant and inquisitive and certainly was fascinated by Greek and Roman art and architecture, literature, and science, including the works of Aristotle and Ptolomy. He is said to have slept with copies of Vitruvius’s works beneath his pillow. But illustrated examples of the Greeks and Romans did not account for a quarter of Leonardo’s engineering devices shown on the 1434 website.

Moreover, whether Leonardo appreciated it or not, he was surrounded by evidence of the Chinese impact on the Renaissance, such as Alberti’s books on perspective in painting and architecture. The basis of Alberti’s work was the mathematics he had acquired from the Chinese explanation of the solar system. Replacing the ecliptic coordinate system used by the Arabs, Greeks, and Romans with the Chinese equatorial system was a fundamental break with the old world, overturning the authority of Aristotle and Ptolomy.

However, that is a far cry from claiming that Leonardo copied existing Chinese inventions. One thing we can be sure of: Leonardo did not meet anyone from Zheng He’s fleets when they visited Florence in 1434. So it appeared that the similarities noted above were due to an extraordinary series of coincidences. Years of research by the 1421 team had apparently been fruitless.