SEVENTEEN

Einstein

1

THE YEAR 1987 WAS THE START OF THE GREAT FALL OF TELEVI-sion evangelists, with Jim Bakker accused of cavorting with Jessica Hahn and paying for her secrecy. Along with him, the Dow reached a record low, Andy Warhol died, and Gary Hart challenged the media to find a black spot on his reputation, which they did with Donna Rice, causing him to withdraw from the presidential race.

After finishing Strangers, Dean turned in another Leigh Nichols book, Shadowfires. He had moved from Pocket when, by the fourth book, it was apparent from the lack of support that they had lost interest in promoting the Leigh Nichols name. Avon had bought it in an auction. It was Dean’s fifth and last book under this pen name, although at that time in the late eighties, he still believed he might keep it going.

He dedicated Shadowfires to his friend and fellow author, Richard Laymon, and to Richard’s wife and daughter. He also framed it with several poems from The Book of Counted Sorrows. This novel, Dean felt, was one of the most frightening he had written to date. In light of how it turned out, he stated thereafter that he would include in his Leigh Nichols books a stronger scare factor. Then Avon identified him to their accounts as the true author behind Nichols, so it seemed pointless to write under two names when he could pour all his energy into one. He wished he had placed Shadowfires under his own name.

In an Afterword to his 1995 revision of The Key to Midnight, Dean explained that there would be no more Leigh Nichols novels, because Leigh had suffered a tragic end. (Actually, Dean proposed several tragic fates for this author — killed in an explosion at a jalapeno processing plant, a rickshaw pile-up in Hong Kong, and a freak limbo incident.)

Told from multiple points of view, Shadowfires’s plot involves a Frankenstein-like inventor, geneticist Eric Leben (the German word for “life”), who makes himself into his own monster. As with the Mary Shelley story, tampering with the human condition for the wrong reasons can have dangerous results. Leben attempts to discover the secret of immortality through manipulation of genetic structures, and when he’s too eager for success, he performs trial runs on himself, despite evidence that some of the experimental mice have become violent. Believing from his parents that he will go to hell when he dies, he is determined to avoid this fate by the simple expedient of living forever! He is also obsessed with youth and control. His inner life is toxic intimacy at its worst: a poisoned soul that cannot heal.

When a garbage truck hits Leben in the very first chapter and kills him, his ex-wife, Rachel, hopes she is finally free of him. She knows about his experiments, however, and certain clues, such as Leben’s missing corpse, lead her to believe he has accomplished his goal. Though he was apparently dead, he is now alive again. Rachel flees with her lover, Ben Shadway, a real estate broker and Vietnam vet (who bears many similarities to Ben Chase). In pursuit are two police officers who are determined to find the connection between the disappearance of Leben’s corpse and a series of murders. Leben’s partner is also trying to find Rachel, as is a government agency (Defense Security Agency), led by sadist Anson Sharp, who hates Ben and who covets Leben’s research. His obsessions associate him with Leben as two parallel images of evil: people of like-minded values are joined in a brotherhood. Against them stand people who oppose chaos, obsession, and destruction. Both types are family, one dysfunctional, the other the ideal of what a human family can be.

The most dangerous of Rachel’s pursuers is Leben himself. Intending to hide out in Las Vegas, Rachel sets out by car across the desert, unaware that Eric is in the trunk. His genetic structure is breaking down and he is transforming into a chaos of primitive evolutionary forms that become progressively more monstrous and bloodthirsty. She manages to escape him, but all parties converge at an abandoned, decaying motel in Las Vegas, where everyone witnesses what Leben has become. They try to destroy him with fire, but it is his own need that brings him down: The mutation process requires more energy than he can feed it. His body cannibalizes itself as his metabolism races out of control — a metaphor of how his obsessions had destroyed him psychologically — until there is nothing left.

This novel expresses the belief that all people must unite against anything — monster, fanatic, dysfunctional family, corrupt government, illicit research — that threatens our humanity. Dean links child abuse to adult deviance, and shows love to be the most compelling healing force. The character types venerated in these pages are intelligent, optimistic, connected to other people, and committed to traditional values. They can grapple successfully with moral dilemmas because they are anchored in a clear sense of self and duty.

Dean’s former Freudian approach to literary development returns when he places Leben’s secret documents in a cellar — the prototypical symbol of the unconscious. Leben’s work throws him back to the most primal id-type aggressions. He has some of Dean’s father’s traits: He relishes struggle but dislikes being deprived; he sees himself as favored by fate; and his intense need is embodied in the most reptilian states — a need that dehumanizes. Like Eric, Ray seemed to Dean to be chaos incarnate.

Rachel has traits that Dean sees in Gerda: She has a fondness for black humor; mocks the absurdities of life; is beautiful, smart, self-controlled, and resourceful. Ben feels good with her, as Dean does with his wife. “By some magic that he could not understand, the sight of her also relaxed him and made him feel that all was right with the world and that he, for the first time in his often lonely life, was a complete man with the hope of lasting happiness.”1 It is perhaps no surprise that Ben shares Dean’s physical appearance: He is five foot eleven, with brown hair and eyes, about one hundred fifty pounds, and he hides a secret past.

The predominant literary images in this novel involve hellfire, the devil, and disintegration. Trying to cheat the devil only turns one into the devil. Dean also uses weather: Rain is a sign of increased emotional intensity.

Shadowfires made it to the bestsellers list, but not until 1993, when Berkley reissued it under Dean’s name. It went to number one at that time in its second week on the list and remained a bestseller for eight weeks. Berkley had paid more than four times the original advance for reprint rights.

Charles de Lint in Fantasy Review called this novel a “top-notch thriller.” Aware that Dean Koontz was the author, he admired the “lean prose,” the “crackling pace,” and the “strong character portrayals.” Another critic, Dale Walker, thought Eric Leben one of the scariest characters Koontz had ever created. “Shadowfires is very strong stuff,” he writes. “There are passages in it more revolting than the worst scenes in the scummiest slasher films — but the violence and blood-letting is offset by the Koontz trademark: a solid love story.”

“The writing is as startling as a banshee’s scream,” was the comment in Parker, Colorado’s Daily News-Press, “and the horror mounts as the pages turn.” That reviewer had trouble visualizing Leben’s monstrous form, but thought the terror quite compelling.

Dean was aware that critics often mentioned the violence in his books. To set the record straight, he addressed this in an interview. To fellow writer Joe Lansdale, he said, “I do believe violence in a novel should have moral purpose. It should not be used merely to titillate, but to show that violence is only a last resort and those who turn to it without compunction are sick.”2 There is a difference, he felt, between using violence to heighten the moral context and using it merely for startling effect, but showing the deleterious effects of violence on society is better than pretending that violence does not exist in our world. To call attention to violence used in a book without making that distinction he thought irresponsible.

2

After Strangers, Dean signed a contract with Putnam for two more novels, getting an advance of $850,000 for the pair. One was to be called Guardian, later changed to Watchers because Berkley had an action series called “Guardians.” The other was Lightning Road, later changed to Lightning when Putnam wanted a one-word title.

Phyllis Grann promised a large advertising budget for the two books with verification that the money was actually spent. Few authors got as keenly involved in the marketing and production of a book as Dean, but he understood the business well enough to know that promises could be made that would never be fulfilled. Ad support was as important an issue as the advance, because it indicated the degree of the publisher’s commitment and helped the author to reach new audiences.

“Dean always wants to know who he’s dealing with,” says Gerda, “so he makes a point of getting to know everyone involved in his production. He wants not merely to know them as business associates but as people, and to feel good about them in both senses.”

The ideas for both Watchers and Lightning had occurred to Dean as he was writing Strangers. He was working seventy-hour weeks and longer on that book, and expected it to take six months to write. When he was six months into it, he realized that he was only half done. He was writing it entirely on spec, money was tight, and he worried. “One day, I was sort of depressed by how long Strangers was taking — and my mind gave me a break from it by suddenly giving me three good novel ideas in half an hour, including Watchers and Lightning. My spirits were buoyed, and I was able to go on with Strangers.”

Ideas might also have come to him so easily because of all his background reading — not just during the writing of Strangers, but daily for years. He read widely in many different fields, from physics to medical technology to psychology, and subscribed to as many as seventy publications per month. He never ran out of ideas for stories, and he believed it was because he fed his subconscious such a rich diet. “I never take notes or consciously look for ideas,” he says. “I dump all this information in and let the ideas boil up, and they’re better than those I might come up with if I were to consciously manipulate the material. I don’t force it.

“Look at the origins of something like Watchers,” he says. He had encountered a quote from Jung, which he used at the front of Watchers: “The making of two personalities is like the contact of two chemical substances. If there is any reaction, both are transformed.” It got him thinking. Likewise, a quote from Teilhard de Chardin, also cited in the book: “Love alone is capable of uniting living things in such a way as to complete and fulfill them, for it alone takes them and joins them by what is deepest in themselves.” About those sentiments, Dean says, “I began to think about the idea that if anyone changes you dramatically, you have an effect on that person as well, and to some extent both people have changed each other. But changing who we are, how we think, what we believe — that is very hard. So the thrust of the book is how difficult it is to change.

“I started with that premise — that change is accomplished not so much on your own, but by finding another person who brings something to you. That person has something you need and you have something that he or she needs in terms of emotional or intellectual interaction. Together you can to some degree transform yourselves, your future, your destiny.

“Then I had a premise about an experiment in a lab, working with enhanced intelligence. A dog that escapes with a human-level intellect. That was my whole premise for the book, along with the idea that it would be about the difficulty of change in the human heart. Then I tried to imagine what sort of character would be most interesting to watch come into contact with this dog, because originally I supposed it would be the wonder of this dog that would change someone’s life. That’s where Travis came from. In the opening scene, he needed to be in a deep state of depression — so that meeting the dog begins the process of change and transcendence for him.

“I was into the book a couple of chapters when the thought occurred to me that something else had to escape from that lab, so I backed up. Then I saw that I’d already created an ominous mood. I had thought I was establishing that people were chasing the dog, but then I realized it wasn’t people, it was something else — some thing else. I had thought that I would have to go back through these early manuscript pages and revise them to accommodate this new idea, but I discovered that the scene was already composed in such a way as to make it explicitly clear that something more fearsome than mere people was chasing the dog. I only had to add a line or two to heighten this.

“For me, this makes it clear that there’s a subconscious at work at all times. I’ve also had the uncanny experience, two-thirds of the way through the writing of a book, of suddenly realizing that other themes can be woven around the central theme to great effect. All I needed to do was go back and implant them. But when I went back, I saw that they were already integrally woven ! When that happens, it gives me a little shiver. And it tells me, if nothing else, that there are deeper levels of consciousness at work at all times.”

Dean took eight months to write this novel, his fiftieth by his count. When he turned it in, Phyllis Grann was delighted with the story. “She loved Watchers,” says Dean. “That was our best experience. We didn’t have any disagreement about it.”

Alan Williams was again the editor. He had met Dean by this time, had heard the stories of Dean’s climb from poverty, and had grown to respect him. He read through the manuscript and felt it was tight. Little revision was needed, and Dean worked no more than a day or two on it.

Watchers refers to what people must be for each other: “We have a responsibility to stand over one another, we are all watchers, all of us, guarding against darkness.”3

3

Travis Cornell, thirty-six and a former member of the U.S. Delta Force, is a man who has lost all the people he loves. He hikes into a wilderness area in Orange County — apparently with the intention of taking his own life. He encounters a golden retriever whose behavior is so unusual and compelling that Travis is drawn out of his depression. When he gradually discovers that the dog is highly intelligent, Travis names him Einstein. The dog then saves a woman, Nora Devon, from a rapist and brings her together with Travis. Although Nora is a timid woman with low self-esteem, Travis helps her to experience her beauty; in so doing, he discovers a reason to live. Together they prove that they can overcome just about anything.

They discover that Einstein is the product of the Banodyne research laboratory, which is involved in recombinant DNA research. The dog can think and communicate at a human level — except that it cannot speak — so they devise clever ways, including the use of a scrabble board, to help him get his messages across. The dog knows that another creature, The Outsider, has also escaped from the lab, and that this aggressive mutant creature was intended to be a killing machine on future battlefields. The Outsider is subtly psychically linked to Einstein, so there is no escape. Researchers from Banodyne are trying to capture both creatures, as are the FBI and a Soviet-hired hitman named Vince Nasco.

Travis and Nora change identities and flee for their lives with the dog they have come to love. When Einstein contracts distemper, they must seek a vet. The vet has an FBI bulletin, but Travis and Nora persuade him of the dog’s abilities and enlist his help. Nasco tries to kill them, but they kill him instead. At the same time, The Outsider arrives and seizes Einstein. Travis corners it and recognizes that it deserves sympathy because it was bred to be evil and wants only to be accepted. In fact, it had ripped out the eyes of its victims because it viewed itself as ugly and could not tolerate the thought that its image alone conjured such terror in its victims. Even so, Travis tries to kill it. Einstein survives, and Nora and Travis find him a mate.

This novel quickly became Dean’s favorite, partly for its theme of remaking families from wounded souls. He later stated, tongue in cheek, that the dog character was modeled on himself. “I like to think that, if I were a dog, I would be as good a dog as he was.” What he especially liked about creating this character, a dog with this kind of intelligence, was that he could make affectionate, bewildered comments about human society and behavior that might seem mean-spirited when coming from a human character.

The novel indicts governmental secrecy, affirms that individuals are morally superior to governments, and emphasizes that while genetic research is necessary for progressively enhancing the quality of life, without ethical accountability, there can be negative consequences.

Dean often remarked that, should he ever write a sequel to one of his novels, it would be Watchers. This book was also one that Gerda especially liked, along with Whispers. “I like them all,” she says, “but those are my favorites.”

Philosophically, Dean examined the concept of personhood in this novel: He had devised an intelligent, loving, protective dog who has all the qualities of the best people, yet still must be treated as a dog. This is a throwback to science fiction days, where a central topic concerned whether aliens or androids could be regarded as persons and thus be given the same rights and privileges as human beings. Where Dean stands on this issue is quite clear: Einstein has a soul, a sense of freedom and courage, and an obvious selflessness. He is more of a “person” than Vince Nasco, and can help create family every bit as much as Travis and Nora.

This novel, along with Shadowfires, which was written at the same time, played with the Frankenstein myth: A scientist believes he can push the envelope, become like God, and create life. However, his experiment goes awry and his creature gets beyond his control. He has foolishly failed to foresee the possible dangers until it is too late.

In addition, there is a strong element of the Jekyll/Hyde motif. Einstein and The Outsider present the disparate parts of an entity, in this case of a laboratory. One exhibited the best traits, the other the worst. Each is merely an extension of human potential and both arise from the same source. The dog’s fear of The Outsider is a person’s fear of his or her own dark side — the destructive potential within, possibly genetically based. Yet the dog’s potential displays what we can become. In a letter to a fan, Dean wrote, “In Watchers, men seek to take on God’s role as creator, and the point is made, both on the surface of the story and on deeper levels, that this is a fitting thing, and that God’s ultimate purpose for us may be to become His equal.”

The first printing for Watchers was 75,000, but by the time it hit the stores, it had gone into several more printings, and had in excess of 100,000 copies in print. It was a Literary Guild Main selection. On February 15, 1987, Watchers entered The New York Times bestsellers list at number fourteen, and it spent eight weeks on the Publishers Weekly hardcover list, getting as high as number eight. Dean was happy and relieved. He had had the impression that the people at Putnam thought his success with Strangers had been a fluke, and now they could see that readers were truly responding.

Simon & Schuster bought the audio rights, and film rights were sold to Roger Corman at New Horizons for $100,000. Dean was to regret the latter decision many times over.

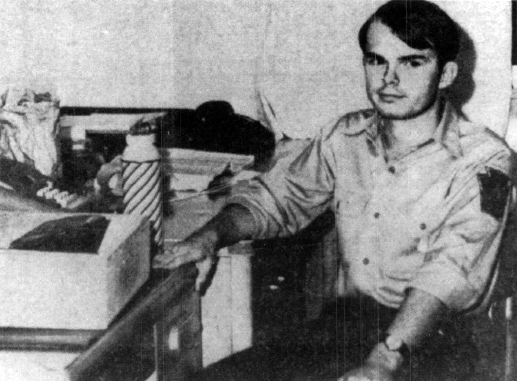

Dean as a Ranger at Shawnee State Park, the day after he was robbed at gunpoint. (Courtesy of the Bedford Daily Gazette.)

Old Main at Shippensburg University. Dean lived in this budding his first year at college. (Courtesy of the author)

Dean and Gerda’s wedding photo, 1966.

(Above) St. Thomas Catholic Church where they were wed.(Courtesy of the author) (Below) Inside St. Thomas Catholic Church. (Courtesy of the author)

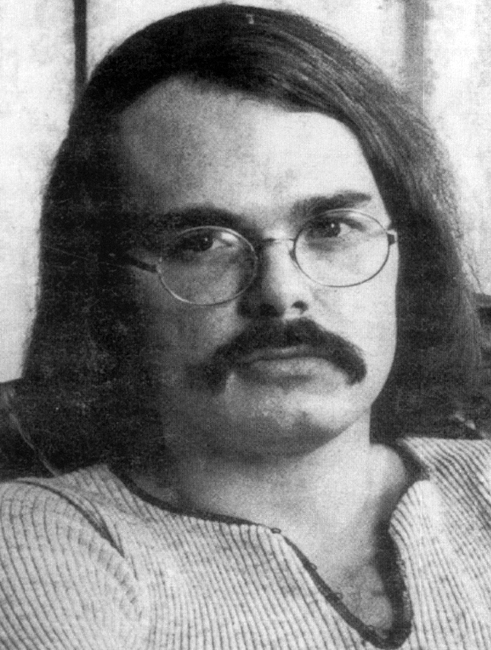

Dean in 1972 promotional photo for Writing Popular Fiction. (Bryson Leidich)

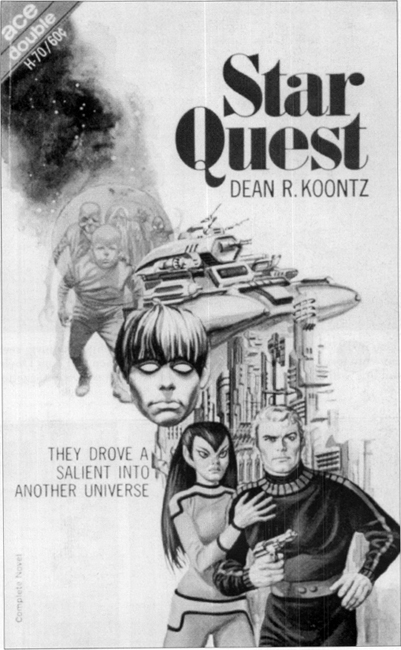

Cover of Dean’s first published novel, Star Quest.

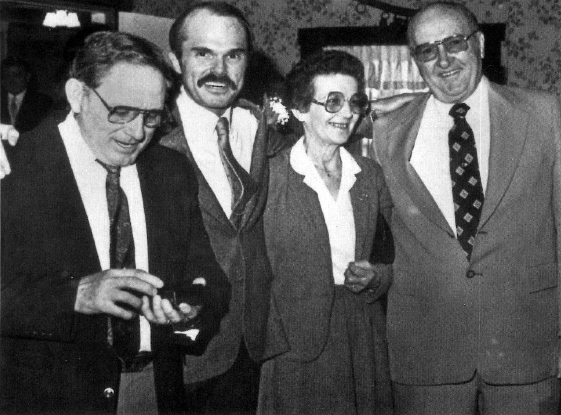

Dean in 1989 when he returned to Bedford and Shippensburg; seen here with former high school teachers, David O’Brien and Tom Doyle, standing with his wife, Marie. (Courtesy of the Bedford Daily Gazette)

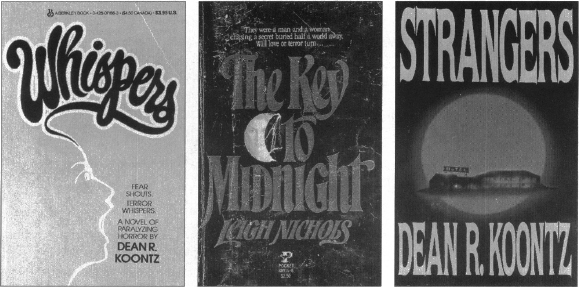

Covers from novels that were pivotal in Dean’s career.

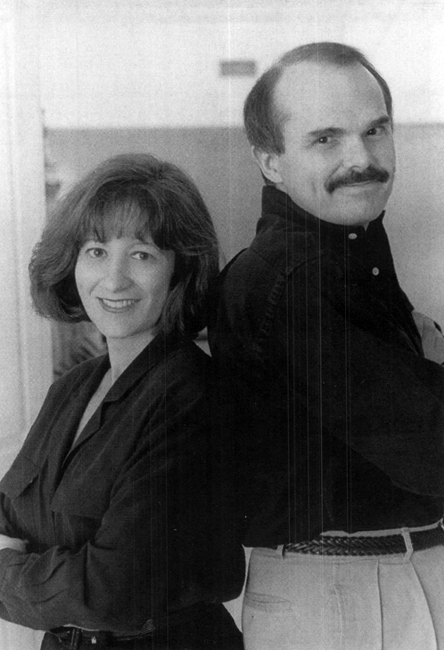

Dean and Gerda, 1995. (Jerry Bauer)

Dean, 1997. (Jerry Bauer)

Reviewers were mostly agreed that this novel had human warmth and merit. Kirkus called Watchers a fable about love and trust, “an imagistic and unusual blend of suspense and sentiment.” One reviewer thought it drew heavily on the plot of the movie Alien, but failed to explain how, while a few thought it lacked plausibility. Publishers Weekly gave it very high marks and called it a cross between “Lassie,” ET, The Wolfen, and The Godfather. Katharine Weber in The New York Times saw Einstein as a rich character and said, “Koontz really hits his stride.” Charles de Lint in the Ottowa Citizen described it as “head and shoulders above standard thrillers,” and noted Dean’s “enviably invisible writing style that propels the story without his voice intruding.” He also mentioned the strong sense of optimism. Jack Pyle called it “as refreshing as an ice cream cone in hell,” while The San Francisco Examiner pronounced the novel “a winner,” giving it a “straight 10 across the board.”

In the Orange County Register, Vern Perry noted the point that Dean made about science and scientific research. “It isn’t what science learns that is good or bad … but rather how that knowledge is applied.” Einstein and The Outsider, he points out, show the two extremes of scientific application.

4

Although money had never been the driving motivation behind Dean’s writing — “And a good thing it wasn’t, because for a long time I made none!” — financial and marketing considerations had limited his creativity through the early years. Once he had felt more secure, he had quickly branched out to test the waters, writing under pseudonyms to explore genres to determine where his greatest skills might lie. Even as he wrote Watchers, he had other irons in the fire. Yet, as with Strangers, he had taken much time developing character and setting. He was happy to finally have the opportunity to thoroughly polish his work. Part of that meant shifting his sense of character from the superficial cause-effect models of much American fiction to what he felt was a deeper, more abiding character development. From the moment he began to write Watchers, he knew that everything was changing for him — his career path, his view of what motivates human behavior, and his experience with the writing process itself.

As he had fully immersed, he had experienced a heightened feeling of productivity. As always, the book had been difficult to write, but toward the last third, when he had gained a clear sense of direction and simultaneous feelings of control and spontaneity, he had an incredible experience. Most of this book had taken eight months, but the last part moved quickly. “It just flew,” Dean says.

It began in Part Two, Section Nine, where Einstein grew ill. Dean began to write and did not stop, save for one break, for two days. “I got up one morning and went to work. I ate a sandwich at my desk, kept going, worked around the clock, and finally fell into bed the next evening, totally exhausted. I slept that night, and the next morning got up and worked twenty-four hours straight. In the first session, which was about thirty-six hours, I wrote something like forty pages. In the second session, I wrote around forty pages in even less time. That’s about thirty thousand words in two sessions, and it needed almost no revision.”

What Dean had experienced is what University of Chicago professor and psychologist Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi calls “Flow.” He had first studied the phenomenon of intrinsically motivated experiences with surgeons and mountaineers who reported a feeling of great joy from complete immersion in what they were doing. He then expanded it to creativity studies. “Action follows upon action,” Csikszentmihalyi stated, “according to an internal logic that seems to need no conscious intervention by the actor. He experiences it as a unified flowing from one moment to the next, in which he is in control of his actions, and in which there is little distinction between self and environment, between stimulus and response, or between past, present, and future.”4

Closely associated with Japanese Zen practices, it is what athletes called being “in the groove,” “playing out of one’s head,” or being “pumped up” or “wired.” Others have called it “peak performance,” the “optimum performance state,” “the zone,” or the “white moment.” It is the context for excellence, involving a sense of effortlessness which results in one’s best work. A tennis player might reach an “impossible” ball or an artist turn out a painting in hours that might usually have taken days or weeks. There is a difference between this experience and simply writing hack work quickly. It has to do with state of mind, combined with skill, confidence, and experience.

Creativity and energy feed each other at such times, minimizing external distractions to the point of perceptual nonexistence. The person in Flow can perform for hours without noticing hunger, external noises, or room temperature. Time seems simultaneously to be faster and slower. The individual feels utterly unified with the task at hand. He is totally present. “The dancer becomes the dance,” said author Louis L’Amour. “I am the writing.”

Flow stretches a person beyond his usual limits. It bonds him with his work, and yields both euphoria and stamina. “Flow,” wrote Csikszentmihalyi, “is the way people describe their state of mind when consciousness is harmoniously ordered, and they want to pursue whatever they are doing for its own sake.”5 Although it appears to be effortless, it evolves from discipline. The best conditions come from a good balance of focus, motivation, organization, vision, energy, and the ability to allow inner resources to be freely expressed.

Centering attention on the merging of action and awareness distorts one’s perception of time and blocks self-consciousness. An easy, yet intense, rhythm develops. Thought and motion become single-minded intention. The individual just lets go and operates as if on automatic pilot. He is an instrument of the work. People in Flow report feeling “most alive” or “at full throttle” — a sense of having been transported into a new, sharper reality.

“If I could do that all the time,” says Dean, “I could write a book in ten days and it would be of higher quality than what comes with endless struggle. You look at something like what happened with Watchers and say it’s uncanny. How is it possible for me to write at the same level on those pages when I struggled with all these other pages at the rate of two or three a day? When I look at the results, it’s actually better than stuff that I worked on for a longer period of time.

“Those are the moments that seem like a form of meditation, or a connection with something else. It’s phenomenal. Time ceases to have meaning. I worked all day and right through the night and into the following afternoon — yet it was only in the last hour or two that I began to feel tired. Then I crashed totally. There was no sense of weariness, no sense of time passing. You look at your watch and think it’s been two hours and it’s been ten or twelve. That is definitely an altered state of consciousness. You have this ebullient, joyful feeling.

“It always looks self-destructive, working like that, and I could never make people — even most other writers — understand that it was not something you totally controlled. Everything is coming to you in an avalanche and you’re not able to get up and walk away. You’re so into it that you don’t even realize how long you’ve been there. It doesn’t happen as often as I’d like. When it does happen, you have to take advantage of it. Stay on the sleigh ride as long as it lasts! Pretty soon, the longer you do it, the greater the momentum, and you remain in that state.”

5

In England, Tim Hely Hutchinson had started Headline Book Publishing in 1986 with two colleagues. “We had known of Dean Koontz’s work for some time,” he says, “and he was very much on our ‘wish list’ of authors we would love to publish, if only we had the chance. To our delight, Dean’s agent sent us the typescript of Watchers only months after Headline had opened its doors for business. This was extraordinary, because Dean’s books were already selling well for his existing publisher, W.H. Allen. We later came to understand that W.H. Allen had rejected Watchers on the basis that it was different from his previous novels and could therefore alienate his established readership.”

As group chief executive, Hutchinson had the opposite opinion. “Watchers was indeed different,” he affirms, “but even better and, far from being the book to sink him, it was the book with which to break him through onto mainstream bestseller lists. It was polished, sophisticated, and grippingly page-turning. It had a brilliant ‘combination punch’ and wholly satisfying ending. Headline bid in the usual British publishing telephone auction — and won.”

Hutchinson found that Watchers performed exactly as he had predicted, which boosted the standing of Headline. “The importance of this for a small start-up publishing company (now one of Britain’s largest) cannot be overestimated.”

Headline went on to publish Dean’s subsequent novels, often getting them into print quickly. They also published a number of novels from Dean’s backhst.

“Dean Koontz,” says Hutchinson, “is a most delightful author with whom to work. To me, he is warm, funny, charming, and profoundly thoughtful. He is immensely well read. Charles Dickens has a special place in his literary pantheon and Dickens’ influence is traceable in a number of ways. I am thinking of the importance of relationships, the intrusion of humor into almost every circumstance, the compelling narrative, and the flashes of pure poetry.”

6

Dean had two articles on writing that year in J. N. Williamson’s nonfiction anthology, How to Write Tales of Horror, Fantasy, and Science Fiction. In one, “Keeping the Reader on the Edge of His Seat,” Dean discusses how to prolong suspense and plant subliminal images to inject more emotional impact into a story. In the other, “Why Novels of Fear Must Do More than Frighten,” he emphasizes the importance of developing character and evoking a range of emotions.

7

Dean urged his agent to approach Pocket to repurchase the rights to his Leigh Nichols novels. The first Leigh Nichols book had been bought by Phyllis Grann when she was at Pocket Books, but she had left, and other editors were less enthused. Shipping problems had taken the edge off sales on The Eyes of Darkness, and the executives at Pocket gradually had lost interest in promoting Leigh Nichols. By the time Dean looked into buying back the rights, Pocket was disinterested enough to hand them over without compensation. “They really aren’t worth anything,” he was told. Insulting as this was, Dean capitalized on it by reselling the rights to Berkley for paperback and to Dark Harvest for hardcover, reissuing them under his own name. “We got the books back,” he says, “and I don’t think it was more than two years later that Berkley bought all these for half a million per book. The first one they reissued was The Servants of Twilight, which spent six weeks at number one on the paperback bestsellers list. That was an enormously satisfying moment. And it’s an instructive lesson to young writers. First, always consider your copyrights as valuable properties. Second, don’t assume that publishers have any idea of what is valuable and what is not.”

8

To the 120,000-word Twilight Eyes that Dean had written for Chris Zavisa’s Land of Enchantment Press in 1984, he added an 80,000-word sequel.

Juxtaposing events and music from 1964 with the characters’ moods, the second part opens with Slim learning about the Kitty Genovese murder in New York, in which thirty-eight people had turned deaf ears to her screams for help, had even watched from their windows as she was repeatedly stabbed. This self-protective, self-centered inhumanity seems unbearable to Slim. He and Rya decide that their work against the goblins is not over. Like the neighbors of Kitty Genovese, if they know of the murderous evil in their midst and do nothing to stop it, they are guilty of the crime of passivity. So they return to Yontstown, Pennsylvania, to kill more goblins. They discover that the Lightning Coal Company is the central nest, and with the help of sevenry-four-year-old Horton Bluett, they infiltrate and blast it open. Five hundred goblins die, but their attackers recognize that this is only one of many such goblin centers. The goblins have built shelters against a nuclear holocaust that they plan to launch against humanity. They then intend to destroy themselves.

On their way out of the tunnels leading from the demolished shelter, Slim and Rya are injured. Slim believes that Rya is dead, but he carries her as far as he can. Bluett rescues them and Rya returns to life. Slim thinks he may have healed her with powers inherited from his mother. He decides that, rather than risk Rya again, he will leave the goblins alone for now.

Given the healing power of Slim’s mother, there seems little doubt that Twilight Eyes is indeed a story of Dean’s inner cleansing. Having purified his father’s image via transforming Rya (Ray), he now uses his mother’s legacy of love and kindness to make her whole. He can thus retain hope as a pillar of life — for himself and in his general outlook. Just as the sixties generated both tragedy and bubbly music, so too does Slim’s life show how darkness and light can coexist, how terror and hope are constant companions. “Hope … is the most pathetic and noblest thing about us, the most absurd and most admirable quality we possess, for as long as we have hope, we also have the capacity for love, for caring, for decency.”6

Twilight Eyes spent six weeks on the paperback bestsellers list, beginning on April 30, and got as high as number nine.

9

Four of Dean’s short stories came out in 1987, one in Dave Silva’s The Horror Show. The other three were collected together in Dark Harvest’s Night Visions 4.

The Horror Show devoted another issue to Dean in which they printed an amusing interview of him by his own pseudonym, Leigh Nichols. Dean also revised his 1972 “Ollie’s Hands,” and provided a new story, “The Interrogation.” In this tale, the police interview a man who has murdered his wife — again! She is an immortal succubus who is stealing his essence. He describes the various forms of symbiotic relationships and claims that she is a parasite. He wants to be free of her, but fears she will suck him dry.

“Miss Atilla the Hun” is about a valiant schoolteacher, Laura Caswell, and a boy from a bad home who has a crush on her. Laura saves her students from an ancient, life-sucking, chaos-wreaking, plant-like alien called “Seed.” She is like the guardians in Dean’s young life — his mother, Winona Garbrick, Gerda — whose strength and caring had saved him from being devoured by chaos. Laura tells the boy that no matter what kind of home he is from, he always has the capacity to do better. When they defeat the alien, Laura retrieves from it the power to heal. Dean revised this and the other two stories in Night Visions 4 for his 1995 collection, Strange Highways.

“Hardshell” is another disguised struggle between father and son. Detective Frank Shaw has the reputation of having a hard shell but a soft heart. He gets drawn into a battle with Skagg, an unusual type of serial killer: an alien that is seemingly invincible. In a plot that is almost a dress rehearsal for Dark Rivers of the Heart, the two of them are linked by virtue of being of the same species, but Frank lives in peace with humankind, while Skagg is a mad degenerate. Frank knows that existence without self-control is only chaos, and that love, which cannot coexist with chaos, is the force of stability and order. Frank uses his wiles to absorb and defeat Skagg, as Dean would do repeatedly in his fiction to the part of himself that linked him to his father.

The title of “Twilight of the Dawn” came from the H. G. Wells quote that Dean had used for Strangers (and mentioned within the story). He considers this tale to be semiautobiographical in that it features a protagonist who goes through various attitudes toward religion and who, via an experience of the uncanny, ultimately comes to understand the possibility of greater spiritual dimensions. Dean himself had gone from Protestant to Catholic to atheist to agnostic, ultimately believing in the existence of God.

The protagonist, architect Pete Fallon, has frequent arguments with his wife, Ellen, over how he treats his seven-year-old son’s desire to believe in things like Santa Claus, angels, and heaven. Ellen thinks Benny should be allowed his fantasies, but Pete believes firmly in a rational, mechanistic universe and wants to raise the boy as a realist. Religion, he insists, is for the weak-minded, a cult of ignorance and irrationality. Faith in God is tantamount to a stain, stealing self-reliance and intellectual integrity.

Then Ellen dies in a car accident and Benny wants to believe she has gone to heaven. Pete is determined to steer the boy in the right direction. When Benny is afflicted with bone cancer, Pete at last must confront how important it can be to envision a higher power. Even so, he stubbornly refuses to yield, even as Benny begs from his deathbed for his father to look for them in heaven.

Alone, Pete gives up his work, feeling the loss of any purpose. He goes out to a cherry tree where he had once spent time with Benny, and suddenly the tree drops its blossoms — all of them at once. As if that is not strange enough, the next morning, the blossoms are back on the tree and they fall again. In that moment, Pete knows that Benny has sent him a sign; death is not the end.

The innocence of the boy has brought the father into the promise of redemption, although he still cannot take the final step of total belief. Like Dean with Ray, no matter how much the boy wants his father to be like him, no matter how much he himself believes it could happen, there is something in the father that cannot give in. Yet the boy never gives up. He cannot. Neither could Dean. Angry as he was at his father, he was attached by blood to this man and he needed to invite him, at least psychologically, into a realm where change and redemption were possible. Benny could do this with an uncanny experience; Dean was left with only the need to act in a manner different from his father. Keeping Ray in his care at least modeled for his father a kindness that was possible, even if Ray could never comprehend what this might mean.

One of the interesting psychological angles in this story is Dean’s awareness of how a person’s firm struggle to resist becoming just like a parent can result in exactly the thing he or she wants to avoid. Pete had so detested the fanatical religion of his parents that he had become just as fanatical an atheist. Because he was so sure he was opposing them, he was blind to how like them he was. This part of the story serves as a double mirror: to those who believe that it is a simple thing to escape family influence, and to those atheists who believe that their behavior has no similarity to people who are religious.

“It’s always been interesting to me,” Dean says, “that of all the atheists I’ve ever known, I have seen them react to issues as if they believe there’s a God. And I’ve never seen an atheist who fails to have a sense of the uncanny, but they never recognize it as being at odds with their professed lack of belief. They have an appreciation at the unconscious level of the wonder of the universe that is hard to explain in a mechanistic manner. I’ve heard atheists, enraptured, talk about the wonders of nature, using words like ‘miraculous.’

“I’m always amazed at how many people will argue against God by saying that evolution proves there is no God. I don’t discount the theory of evolution, but I don’t think it throws out the idea of a created universe. Evolution could be the mechanism by which God works.

“Likewise, it amazes me when someone says, well, if God was beneficent the world wouldn’t be full of suffering. This assumes that one can know the meaning of life and can know that suffering is without value or purpose. But look how often we learn from our pain, how often we grow and change and mature because of our suffering. Ultimately, you take it on faith or not, but you can’t argue against God’s existence with those flimsy issues.

“Part of the power of the story is the redemption of the father through the son’s innocence. The little boy is the teacher that the father needs, but he’s not just going to grab at faith when he needs it, and in the end he’s still resisting. He believes that he is going to meet his wife and son again, but he won’t take that final step and admit there’s a God. I think the story works because he bullheadedly retains a degree of skepticism.”

When Dean finished this story, he told himself that he would one day base an entire novel on this sense of the uncanny. That book, Sole Survivor, would not be published for ten more years, but when he finally wrote it, the story was more ambitious than he had originally envisioned.

10

While Dean and Gerda were going through a trying time with Ray and his incessant demands, Gerda ran across an article in a woman’s magazine about fertility experiments. She noted that the first artificial insemination experiments had been conducted in 1944, the year before Dean had been born, and that some of the initial trials were conducted through a university hospital in Maryland. Because the nature of these experiments was controversial, the physicians had used couples who were likely to be discreet: those with no more than a high school education, childless, in the lower economic classes, and living in rural areas in Pennsylvania. Such women, profiles predicted, would be most likely to honor confidentiality clauses.

Gerda felt it was a perfect description of Dean’s own mother. She brought it to Dean’s attention, and began to think more seriously about the possibility that Ray might not be Dean’s biological father. His parents had always called him a “miracle child,” because they had been told they could not have children; his father had not fathered other children in all his adulterous liaisons (Dean did not know then about his mother’s numerous miscarriages); Dean bore no physical resemblance to Ray; the sperm donors had been highly creative people, such as composers and writers, while no one in Dean’s family had shown this kind of talent; Florence had tried to tell Dean something before she died about his father — something he “had to know.” Perhaps that he was not Dean’s father after all? It all seemed logically to add up.

“What I found interesting,” says Dean, “was that my mother couldn’t seem to have a baby until she went to a certain doctor. He was a GP, but GPs didn’t have procedures in those days to help women get pregnant. Yet if it was by artificial insemination, the institution would have needed local doctors to liaison between them and their patients.”

Yet if Florence had indeed volunteered for such a procedure, she kept it even from her sisters. Nancy Eckard, who listened to Dean’s Aunt Kate talk about all of Florence’s birth difficulties, claims she never said a word about this possibility.

The idea continued to intrigue Dean, but he also had not given up the idea that his Uncle Ray might be his father. He had not forgotten the mysterious conversation he had heard between Uncle Ray and his mother.

11

After Watchers was published, People magazine featured an article on Dean. They sent a photographer, Jim McHugh, who spent three days taking pictures from various angles. After the first hour of the first shooting session, he said to Dean, “You’re a child of an alcoholic, aren’t you? I can tell because you need to be in control.”

There followed a conversation about adult children of alcoholics — a cultural awakening that was sweeping the country via group therapy, books, and workshops. Dean listened to what the photographer had to say and began to better understand his obsessive-compulsive drive, his need to create a stable environment, his fear of flying, and his inability to believe that his success had a firm foundation. McHugh explained to him the traits that many people who have come from such homes share, and Dean’s subsequent reading provided the rest: they often block out pain with some other addiction; they excel at things they can control; frequently they feel insecure; they tend to hope for the best but expect the worst; they take care of others before themselves; they find self-worth largely through work; they allow others to demand too much of them; they have a need to appear picture-perfect; they are survivors; and they tend to fear a return to the chaos and desperation that they once had known. Yet, often, they set themselves up to do just that.

Dean understood that his father’s addictions and mental illness had affected him profoundly. His father’s periods of rage or tense silence, the uncertainty, the emotional abuse — all of these had influenced who he was and who he could become unless he shaped his own life with an iron will. To be driven and addicted to his work was not a bad thing, as long as he found some balance: to keep some semblance of control, to excel, to be a survivor. These were positive things if kept in perspective. The difficulty was to avoid giving in to the negative forces spawned by that background. He knew he would struggle against those the rest of his life.

He realized that he and his mother both had been codependent through those years of hardship, enabling Ray to continue with his behavior by rescuing him from bars, not expressing their own needs, and generally allowing the situation to persist. To some extent, Dean thought, even now as an adult, his care for Ray might have an element of codependence.

Not long afterward, Dean had cause to see how dangerous his father really was. Ray had suffered a stroke a few years earlier and was aphasic, but he was still capable of living on his own and was still physically powerful. Through the years, he had continued with his habit of calling Dean and Gerda at night to take him to the hospital. Finally Dean decided to try to put a stop to this by going over to Ray’s apartment one night and just sitting there with him. If he really needed a doctor, then Dean would take him, but otherwise, he was not going anywhere. Ray insisted on going to the hospital, but Dean refused. He knew that what his father was after was the attention he got from the hospital staff, but he did not want to take the chance that the one time he decided not to come would be the time something was really wrong. So to cure Ray of these incessant calls that amounted to nothing, Dean drove him crazy by just coming over and being with him. That was not what Ray wanted.

Dean waited until dawn, and then went home to sleep. The following day, on September 6, 1987, Gerda went over on her own. Ray again asked to go to the hospital and she refused. He grew angry, and at one point, he got out the butcher knife for no apparent purpose. Immediately she left to go pay his rent. She alerted Dean to this event, and when they went back later together, they were watchful. Dean reluctantly agreed to take Ray yet one more time to the hospital. “But if it turns out, as always,” he said, “that your symptoms are psychological, then you’ll have to move from this apartment to a retirement home with closer supervision.”

The problem was that Ray often overdosed — or sometimes simply did not take his medication. Eager to get to an emergency room and be the center of the nurses’ attention, Ray agreed to the terms.

Dean turned toward the door, but out of the corner of his eye, he saw Ray’s hand stray to check his pants pocket. “When I looked back, he still had his hand there and between two spread fingers, I could see this shape. I asked him what was in his pocket.”

Ray pulled out a yellow-handled fishing knife with obvious violent intent, and Dean had to wrestle it away from him. Dean and Gerda then took Ray to be evaluated. He was in the hospital for ten days, and they learned that he was suffering from degenerative alcohol syndrome. He would need to start taking antipsychotic medicine.

At that time, Dean considered asking the doctors to run a DNA analysis, to determine if he really was Ray’s son. Even if he was not, he knew he would continue to care for this man because someone had to do it. Gerda encouraged him, but he put it off.

They were faced with having to move Ray to a more secure place, so they chose Casa Orange Retirement Home. The ordeal, however, was far from over.

1Dean Koontz writing as Leigh Nichols, Shadowfires (New York: Avon, 1987), p. 32.

2Joe R. Lansdale, “Dean of Suspense,” The Twilight Zone, (December 1986), p. 23.

3Dean R. Koontz, Watchers (New York: Putnam, 1987), p. 419.

4Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi, Beyond Boredom and Anxiety (San Francisco: Jossey-Bass, 1975), p. 36.

5Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi, Flow: The Psychology of Optimal Experience (New York: Harper & Row, 1990), p. 6.

6Dean R. Koontz, Twilight Eyes (New York: Berkley, 1987), p. 183.