Told to me in Bemba by Godfrey Chanda, a subsistence farmer near Kalamazi rose farm, outside Lusaka, Zambia

Once, a long time ago, the earth was perfectly stocked with food and water. Every river ran clear and sweet. Every tree hung with fruit. Every blade of grass was green and crisp. There were treats around every riverbend and every mountain top for the animals to eat and every creature on earth was fat and happy.

There was so much food that, one day, King Lion decided to celebrate with a feast. ‘Gather your favourite foods and let’s meet this afternoon under the fig tree,’ he announced. ‘This will be the greatest of all feasts.’ The jungle was a mass of moving animals as everyone hurried about, gathering their favourite titbits: marula berries for Elephant, river-grass for Hippo, sausage tree fruit for Giraffe and soft roots for Hare.

At sunset, everyone met under the fig tree and began munching and crunching with gusto, from the tall giraffe crunching his succulent sausage fruit to the tiniest bat softly sucking its guava. By midnight, everyone had had a marvellous time – except one poor old creature: Tortoise. The slow fellow had taken so long to gather his favourite cabbage leaves that by the time he arrived, the party was over and his friends were burping and barking and heaving their fat bellies off to their beds.

Tortoise was very upset. As he sadly trundled home, he passed some birds in a tree. ‘What’s wrong, Tortoise?’ they asked, chirruping and cheeping. ‘Why are you crying?’

‘The animals had a feast today, and I am so slow I missed it,’ wept the tortoise. ‘I was looking forward to a chat over a bit of wild cabbage, but when I arrived, no one wanted a nibble or a natter.’

The birds felt very sorry for Tortoise. His face was so tear-stained and his mouth looked so downturned that there was only one thing they could do: hold their own party the next day. ‘And you will be our guest of honour, Tortoise,’ they smiled. Tortoise was very excited. He had never been to a birds’ party before. Then his face went glum again. ‘Birds usually have their parties up in the sky,’ he complained gloomily, ‘and I am a big heavy tortoise. How I am I going to get up there?’

He had a point. How were they going to fly him up to their favourite cloud, the birds asked. Then Kingfisher piped up. ‘I’ve got an idea,’ he chirruped cheekily. ‘What if we birds each donated a feather to Tortoise, and the bees gave some wax to stick them on? Wouldn’t he then be able to fly up to the sky?’

The birds all agreed that was a marvellous idea and one by one they flew down to give the shelled creature a feather. First came King Eagle with a big glossy one, then Vulture with a speckled one, followed by Hawk, then Bulbul, then Sparrow, then Weaver, then Ibis, and Stork, and flocks and flocks of tiny, rainbow-shaded birds. Before long, in front of Tortoise’s scaly head, lay a magnificent array of green, blue, black, white, yellow, red, striped, speckled and dotted feathers – gifts from the smallest finch to the largest ostrich.

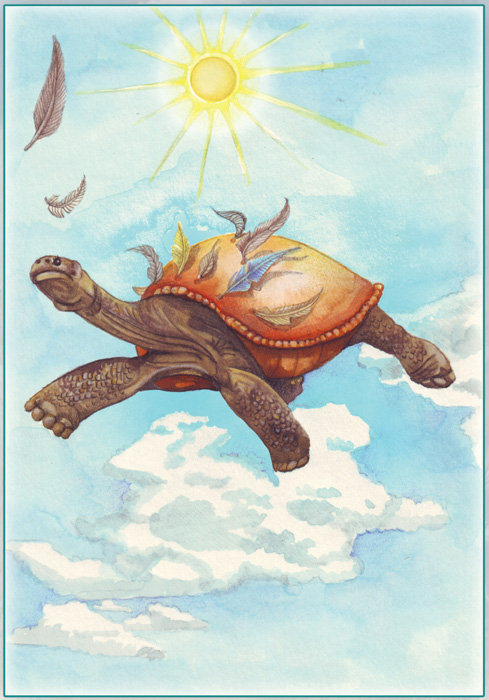

Tortoise had never had so many gifts before, and once his friends, the bees had kindly spread their yellow wax onto his shell and his legs, and buzzed about sticking the feathers down, a great grin spread across his face. With a run, a jump and a flap of his little legs, Tortoise was soon airborne, and whizzing up high towards the birds’ cloud in the sky.

When he reached the cloud, he couldn’t believe the feast the birds had assembled. There were green grasshoppers and geckoes. Plates of red ladybirds and wriggly worms. Crawly caterpillars and traily snails. And trays and trays of leaves, and cabbages, and grass, and fruit. What a feast!

Tortoise’s mouth started drooling. But before anyone was allowed to eat, King Eagle asked them all to introduce themselves to their new guest. ‘I am Kingfisher,’ said the kingfisher, flying forward and flashing his emerald wings. ‘I am Warbler,’ sang the sweet-voiced warbler. ‘I am Egret,’ fluttered the dainty white egret. Then the sparrow stepped forward. ‘And who exactly are you?’ he asked Tortoise.

Tortoise looked confused. ‘Well, I have everybody’s feathers on my back, so I suppose I am Everybody,’ he said. Then King Eagle stepped forward. ‘Now the introductions are over, I open the feast. It is for everybody, so everybody tuck in.’

The birds looked confused. Was it for them? Or was it for Everybody the tortoise? Politely they held back, and watched as their guest tucked into the wonderful feast. Head down, eyes to the floor, Tortoise munched and crunched, without looking up once. First he gobbled all of the birds’ favourite foods, which he didn’t normally eat: the grasshoppers, then the geckoes, then the ladybirds and wriggly worms. Then he crunched his way through the caterpillars and snails. And once he had devoured that, he started munching on the all of his own favourites: piles and piles of lovely lush leaves.

The birds weren’t pleased with Tortoise’s rudeness – especially when he casually announced he was going. ‘At least you could say thank you,’ muttered grizzly Owl. ‘Or offered to share a worm, which we know you don’t even like,’ muttered Crow. ‘Or halved a caterpillar,’ grunted Egret. But, no. Tortoise was selfish. He was used to living alone, and not sharing, and so, when he finished his feast, he licked his lips and turned around to fly home off the edge of the cloud.

The birds were furious. How dare Tortoise eat all their food and not say thank you? If he was going to be so rude, they decided, they were all going to take their feathers back from him. So, in a great flock, the birds all swooped on Tortoise, each pecking their feather off his back. And slowly, Tortoise felt himself sinking deeper and deeper into the cloud.

‘Help!’ he cried, as he sunk into the whiteness. ‘Help, someone!’ But not a single bird came. ‘If you think you are Everybody, then help yourself!’ they squawked, flying away crossly to their nests.

Of course, without feathers, the heavy Tortoise fell to the earth with a tremendous thud. The landing was sore and very undignified. But even worse than that – it had ruined his shell. His once beautiful, glossy, glamorous outer layer was gone, and in its place was a shattered mess of a hundred tiny squares.

Today, if you look at a tortoise, its shell is still cracked. The gods left it that way as a reminder to all creatures – of what happens when you take your friends for granted. Love them and you will fly high. Forget them and you will fall. Just like Tortoise did.

Told to me in Ndebele by Lindani Nlotshwa in Bulawayo, Zimbabwe, and in Bemba by Godfrey Chanda in Zambia

Once upon a time, long back, when animals could talk and Hare had a long tail, there was a terrible drought. The leaves shrivelled up. The puddles turned to dust. And the waterholes slowly dried and cracked, leaving the animals with nothing to drink. Even when they prayed to the great Rain God, the air remained empty and dry, without a single cloud in the sky.

King Elephant became desperate. He hadn’t had a drink for two days, or a mud bath for a month. So he decided to call a meeting. ‘Cheetah!’ he trumpeted to his chief messenger, who was lying in the shade, trying to keep cool. ‘Go and call all the animals. We must meet.’

Being the fastest animal on earth, it didn’t take Cheetah too long to relay the king’s message. He ran from river to rock, from grassland to grotto, and from treetop to mountain top until, by the end of the day, the animals had all gathered under the great baobab tree.

When they had all quietened down, the Elephant began. ‘Subjects,’ he trumpeted, swaying his body importantly from side to side. ‘We are in grave danger. Our waterholes are almost dry, and soon we will die of thirst. Either we must move to a wetter area, or we must make a plan. I’ve given up on my ideas. So if anyone else has one, would he please step forward.’

At first no one said anything. Then Impala and Gemsbok, the shy little buck of the bush, started to whisper to each other. ‘Speak up, speak up!’ thundered Elephant. ‘If you’ve got something to say, trumpet it out, trumpet it out!’

‘Well, Your Majesty,’ whispered Impala, his skinny front legs shaking with nerves, ‘what about digging a well? If all of us helped, it wouldn’t take long. We could take it in turns to guard it, day and night. And then we might have water for ever.’

The animals couldn’t quite believe that such a big idea had come from such a small creature. ‘You are quite brilliant!’ said the king proudly. ‘Tomorrow, as you have suggested, we will start digging. And you will be the first to be rewarded with the sweet water when the well is finished.’

The next day, as agreed, all the animals gathered in a sandy spot by the riverbank to dig. Every animal, that is, but lazy Hare. ‘Me?’ Hare said, flicking his beautiful, long, fluffy tail. ‘Why should I want to drink from your silly well? I have juicy roots to gnaw in my burrow, and an underground spring to sip from. Thanks, but I’d rather have a snooze here in the shade.’

Digging a well took a whole day, but at the end of it, the animals heard a wonderful sound coming from the bottom. ‘Water!’ Python gurgled, as he slowly floated up on a bubbling pool of liquid. Excitedly, the bucket was passed to the front, and as promised, when the first bucket was drawn Impala was given the first sip. The water was not only cold. It was sweet, pure and clear – the nicest water anyone had ever tasted.

Over the next weeks, as the earth became drier and drier, the animals congratulated themselves on their magnificent well. Only Hare wasn’t happy. The spring had disappeared from its underground spot, and the roots had shrivelled and dried.

But whenever he tried to get to the well, some fierce creature was guarding it. And the animals all said the same thing. ‘Sorry, Hare, but you didn’t help us to dig, so you can’t drink either. Goodbye.’

Hare was becoming very cross. He couldn’t be bothered to dig his own well. He didn’t fancy pleading with the king for water. So there was only one thing left, he decided to steal it.

That night, he crept quietly behind the well, and with just a little hop, he was at the bottom, sipping lovely cool, sweet water. ‘Hahaha, you are a clever chap!’ he laughed to himself, as he inched his way back up. But Hare was not quite as clever as he thought. The watchful guard had spotted him leaping in, and immediately called the animals. Just as Hare got to the top, he was caught. Then a great roar erupted into the night. ‘Hahaha,’ laughed Hyena. ‘Hisssssshissss,’ hissed Python. ‘Snortttttt, snortttt,’ huffed Hippo. ‘We have caught the water thief!’

Even King Elephant had a triumphant trumpet, before quietening the animals for Hare’s formal dressing down. ‘Hare, you are a disgrace to the animal kingdom,’ he harrumphed haughtily. ‘Not only have you been lazy, and failed to help us dig the well, but you have stolen water that doesn’t belong to you. You must be punished.’

Hare’s long tail started to quiver with terror. ‘King, oh, King,’ he said. ‘I know I have done wrong. But whatever you do, please don’t swing me by my ears and tail and throw me onto the sand. That’s what every hare dreads.’

Elephant surveyed him with a frown. ‘If that is what hares dread, then that is what we must do,’ he said. He called for the sharp-toothed dog to hold Hare’s long tail and Hyena to hold the rabbit’s ears. Then, as the animals roared and snorted, they swung Hare into the air and thumped him onto a pile of yellow sand. When he lay there quite still, there was a rumbling cheer. ‘Justice has been done!’ the animals yelled. ‘Let’s go and celebrate.’

But as usual, Hare had tricked his fellow creatures. No sooner had they turned their backs than he leapt up, gave a gleeful shout and then hopped for his life. ‘Silly animals,’ he giggled as he bounced this way and that. ‘Don’t they know how soft sand is? It’s like a pillow to us hares!’

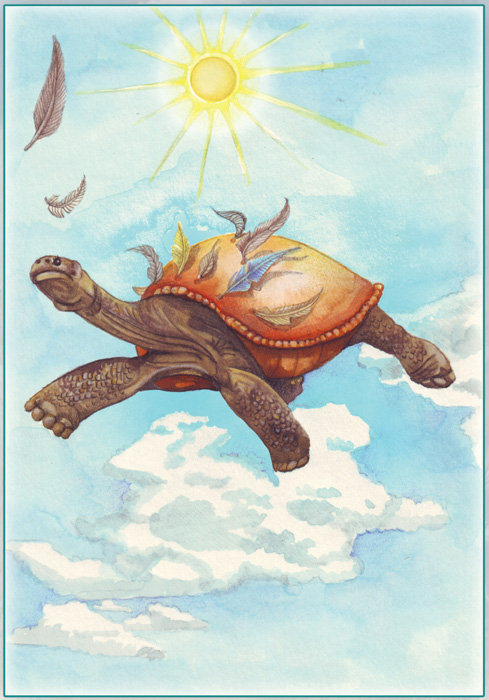

The animals hated being tricked once. But being tricked twice was really out of order. ‘After him!’ trumpeted Elephant furiously, as the paths pounded with creatures in pursuit. Lion was at the front, but before he could even yell ‘Burrow!’ Hare was down one, his long tail slinking swiftly down the hole. Sadly, it didn’t slink down quite fast enough, and with a pounce Lion caught it and bit it off sharply between his teeth.

Hare howled and cried, and hopped up and down with agony, but it was too late. His beautiful long tail was gone – lopped off by Lion. Look at it today, and see how stumpy it is – a constant reminder that Hare had cheated – and lost.

Told to me in Tonga by Mafuta Siabwanda in Bulawayo, Zimbabwe

Once upon a time there lived a woman called Lefu, who was loved by everyone in her village. Lefu was poor, but she was generous, kind and always smiling, especially when she was with her daughter Minni. She loved Minni. Every day, when they’d take their clay pots to get water from the river, she would sing a song to thank the god Mulungu for such a happy life. ‘Thank you Mulungu for food, sun and water, and thank you for giving me my precious daughter,’ she sang sweetly, as her friends the birds whistled along.

In the same village lived three women, who had plenty of earthly riches, but were terribly mean. They never shared anything – their food, their conversation, or their song – preferring, rather, to sit in their huts, counting their pieces of cloth, admiring their goats, stuffing their fat bodies with porridge, and complaining.

Complaining was their favourite hobby, particularly if it was about Lefu. ‘Why should she be loved more than us by the rest of the village?’ they would gripe through their mean mouths. ‘We are much richer than she is. All she has is that silly smile on her face.’

One day their jealousy became so great that they could not stand Lefu’s smile any longer. They came up with a horrible trick to play on her. At the hottest part of the day, when Lefu and Minni were gathering water at the river, the three women appeared from behind a tree. ‘Hello, Lefu,’ said the first woman, a fake smile lighting up her normally mean face. ‘The sun is so hot today that all three of us have thrown our children in the river. They are so happy and cool now. Why don’t you throw Minni in? The poor girl looks boiling!’

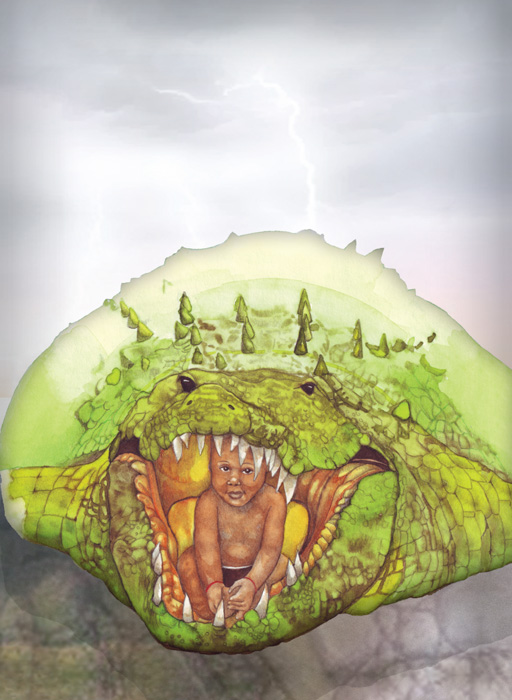

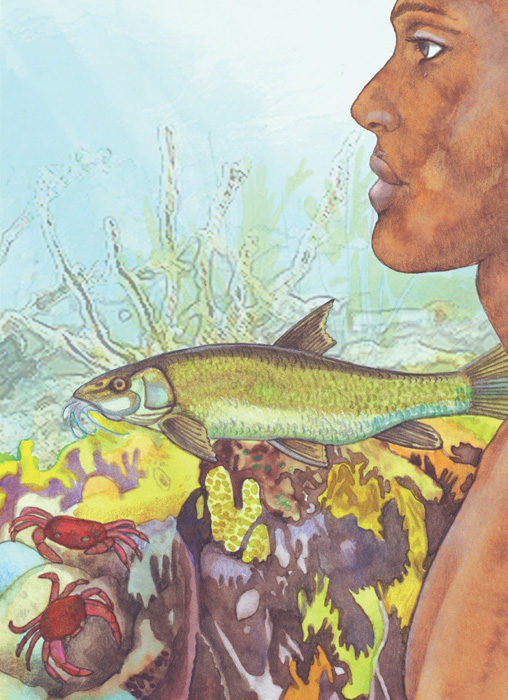

Lefu was a bit apprehensive, but her daughter looked so hot, and the women seemed so unusually helpful, she agreed. But the minute that Minni’s body splashed into the water, the three women began to cackle through their yellow, cracked teeth. ‘You love making people happy, Lefu,’ hooted one noisily, ‘and today you will have made Crocodile’s day. He doesn’t usually get plump young girls for his dinner.’ Before Lefu could even cry out, Crocodile had risen from the river bed, snapped up Minni and vanished under the water.

Lefu was distraught, and ran back to the village crying out for the village warriors to come and help her. They took their spears to hunt the great beast. But it was too late – Crocodile had vanished, with Minni in his belly. ‘Oh God Mulungu, who gives me food and water,’ wept Lefu under a tree by the riverbank. ‘Please help me to get back my precious daughter.’

Leopard, who had been lying eating an antelope on a branch above Lefu’s head, took pity on the weeping woman who usually sang so sweetly. ‘Lefu, climb up here,’ he purred softly, ‘and I will help you find your way to the great god Mulungu. It is a long journey into the sky, but if you climb my tree, at least you’ll be nearer the clouds.’

So, with Leopard’s help, Lefu climbed the tree to the tips of its strong branches. When she got to the top, her friends the birds offered her further assistance. ‘Come with us, sweet Lefu,’ they sang, lifting the woman onto their wings and flying her into the sky. When they reached the stars, the great fishes of the sky, the Mazomba, took over. They lifted Lefu from the birds, and swam her through the stars in the great Lake Sky. Eventually she reached the village where the great god Mulungu lived.

When Mulungu heard her sweet voice, the god immediately recognised the sweet woman who sang praises to him every day, and took pity on her. At once he ordered Crocodile to come and see him.

‘I know Minni was your supper, Crocodile,’ said Mulungu, ‘but Lefu needs her beloved daughter back. I promise that, if you obey me, I will see that you have plenty of food to make up for that snack of little Minni.’

This sounded like a good deal to Crocodile. So he belched, and his tummy squelched, and out of his long, toothy mouth popped a slightly wet, and squashed-looking, Minni. ‘Oh thank you, Mulungu,’ cried Lefu happily, hugging her daughter and drying off Crocodile’s saliva. Then the two of them set off home again – this time with their new friend the Crocodile, and a great bundle of gifts from the god for their journey.

When they got home, the villagers prepared a celebratory feast and Lefu sat round the fire and told them of her great adventure in the sky. When she showed them Mulungu’s gifts: cloth and food and gold, the villagers were delighted for the sweet Lefu – except, of course, for the three greedy old women. ‘Why should that silly, smiley Lefu have those gifts?’ they complained. ‘If she can trick Mulungu into giving her all that, surely we could have even more?’

So the next day, the three women threw their own three children into the river, and, huffing and puffing, hauled their fat bodies up the tree where Leopard lived to make the long journey to the great god Mulungu. The trip took them much longer than Lefu’s, as none of the animals wanted to help such miserable, miserly old women. But after a few days of beating and prodding the reluctant birds and beasts, the three women arrived at the god’s village.

Mulungu was not pleased. After all, gods don’t like to be ordered about. They don’t like their animals being maltreated. And they especially don’t like lazy, malicious, mean old women coming to lie to them. At first Mulungu listened patiently to the women’s sob story, of how they had mistakenly lost their beloved children in the river, and how their dear friends the animals had helped them reach the village.

But slowly his face darkened, and his voice turned to thunder. ‘Old women,’ he bellowed, as the rain clouds around him turned black.

‘Have you not learnt any lessons in life? You have done every bad thing a woman can do – fooling a mother into killing her daughter, lying, throwing your children into the river, and now trying to trick me into giving you things. Well, if you want things, you will get things. But it will be things that you deserve!’

The god then raised his hand furiously into the sky. As he did, the clouds blackened, the wind started to blow, and a monstrous bolt of lightning shot from his palm, striking all three women down and throwing their bodies down through the sky into the river for the hungry crocodile to eat.

The village was glad to be rid of the three wicked women, and to welcome home Minni and Lefu. But no one will ever forget that day: the time that Mulungu took the liars and sent them back to earth in lightning. Whenever there is lightning, liars look particularly nervous. For they know it is a sign that the great god Mulungu is watching for wickedness from above.

Told to me in English by Aubrey Mbewe, a game guide at Kisani Lodge in the Luangwa Valley, Zambia

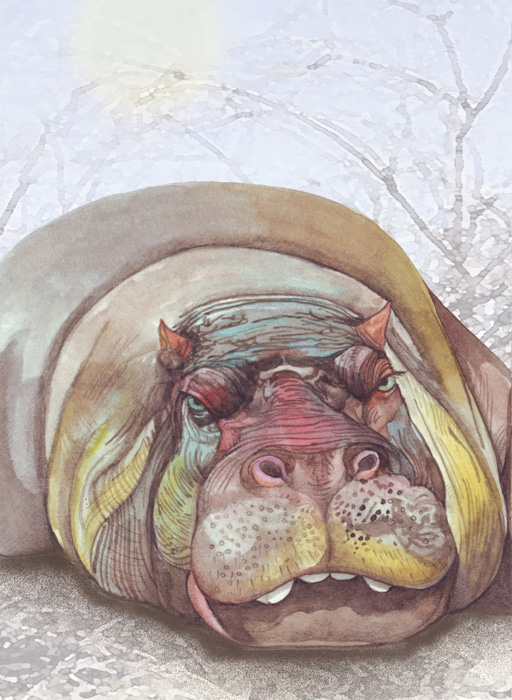

When the Creator first made the earth, Hippo was a land creature. A greedy land creature. All day he would wander the riverbanks and plains, chewing and chewing and chewing. The more he chewed, the fatter he got. And the fatter he got, the more he hated the hot African sun.

‘Oh great God,’ he muttered miserably as he heaved his fat, hot belly down to the river for a drink. ‘I wish I could cool down. How I envy those creatures that don’t have to bake in the sun, but who wallow happily in the water. I wish I could join them.’

One day Hippo could take the baking sun no longer. His skin was wrinkled and cracked, his nose was sunburnt and he could hardly talk his mouth was so dry. ‘Please, Creator,’ he begged. ‘Let me go and live in the river. I am so unhappy in the sun. I promise I will behave.’

The Creator wasn’t convinced. ‘Everywhere you go, Hippo, you eat everything in sight,’ he said. ‘On the riverbanks you eat the river plants. On the plains you eat the grass. If you lived in the water, you would undoubtedly eat all the fish too. Besides, what would the crocodiles say? It’s their home too, you know. And we can’t have two hungry animals living in the same water. I’m sorry, but the answer is no.’

At this news, Hippo wept and wailed. By day he heaved his fat belly around, chomping grass and drinking water. And at night, he complained by the light of the moon. ‘Oh Creator, please!’ he wept.

‘Today my nose got sunburnt, my ears got sunburnt, and even my tummy got sunburnt. I’m so unhappy in the sun that I am prepared to make you a promise. I promise that, if you let me live in the water, I will only stay in it in the day. By night I will get out of the river and eat grass by the light of the moon. And never, ever will I touch a fish. I promise, I promise, I promise!’

The Creator, feeling sorry for the poor sunburnt Hippo, agreed – on one condition: that the fat creature never, ever ate a single fish. ‘And to prove it,’ the Creator said, ‘every time your food passes through your body, I want you to spray it around with your tail. As your dung flies through the air, Hippo, I will personally inspect it. If I ever see a fishbone in it, I’m warning you, you will be out on the riverbank in the sun again.’

Thanking the Creator, the very happy hippo jumped straight into the water, where he still lives today. Occasionally during the day you will spot his nose and ears poking out of the water while he keeps his body cool under the water. But he always comes out at night to graze, and whenever he does you can see him keeping his promise to the Creator. Watch his tail you will see it spinning about, sending his dung flying into the sky. And occasionally you will hear him grunt ‘Look, God, no fish, Look God, no fish!’ just to prove his point.

Told to me in Shona by Blessing Cabbage in Mabvuku, Zimbabwe

A long time ago, before Lion was king, Elephant was the ruler of all creatures on earth. He was the biggest, the strongest and the wisest animal God had ever made, so it was only natural that he should rule the kingdom.

One day King Elephant decided to call a meeting of all of the antelopes. This was unusual, because normally he invited everyone, but this time he needed to discuss something that concerned the antelopes only. So he sent out an urgent message calling all the antelopes to meet under the baobab tree.

Hare, as usual, had his ears pricked into the air, and soon he had heard the message too. He was very cross. Wasn’t he smarter than anyone else? Craftier than anyone else? And faster than everyone else? If so, why was he being left out of the secret meeting?

For two days and two nights Hare sat grumpily in his burrow. ‘How am I going to get to the meeting?’ he pondered. Then at last he came up with an idea. ‘I know!’ he giggled, hopping about happily in his burrow. ‘I will make myself into an antelope!’

After making sure that no one was watching him, Hare set off in great excitement. He hopped and he skipped, over logs and over the river. When at last he got to a hollow tree in the forest, he gave a leap of joy. For there was a tree trunk containing the most enormous deserted bees’ nest he had ever seen. And in that nest were honeycombs full of precious golden wax.

Hare couldn’t stop grinning. ‘Hohoho!’ he chortled happily, hopping from foot to foot with glee. ‘Look what the bees have made for me!’ And quickly he began stuffing his little bag full of wax, before hopping home.

When he got back to his burrow Hare wasted no time completing his plan. With his deft little fingers, he soon was shaping, smoothing and shining the wax until, in his hands, he held a pair of the most beautiful, elegant and realistic antelope horns he’d ever seen. He tried them on for size, adjusted them between his two short little ears, and wiggled his head about to make sure they stayed on. Then, with a contented sigh, he settled down for the night, dreaming of how handsome he would look as an antelope.

The next morning, Hare leapt up and excitedly tried on his new headdress, sticking it down firmly with wax on his head. After looking at himself in the waterhole, he had to congratulate himself. ‘The animals are right, Mr Hare,’ he said, swaggering at his reflection, ‘when they say you are a handsome and clever chap. Indeed you are! Yes, you are!’ And off he trotted, as antelope-like as he could, to the secret meeting.

Under the great baobab tree, the antelopes had all gathered, and were snorting and harrumphing in anticipation of the big occasion. All types of horns were mingling together. On one side stood the bighorned animals: Eland’s curly and twisted, Sable’s notched and arched, Waterbuck’s black and straight. And on the other stood all the tiny buck, from Duiker to Impala, wiggling their little horns and snorting impatiently.

Nervously, Hare slipped in between them, lowering his head so no one would notice him. Fortunately, most of the antelope hadn’t seen each other for a while – some being from the mountains and others from the valleys – so they took little notice and kept on chatting. And soon, King Elephant was trumpeting the start of the meeting.

‘As you know, oh Horned Ones,’ started the king, ‘we are here for a secret meeting to discuss matters related only to us. I would ask you to keep whatever you hear to yourselves.’ The antelopes all nodded in unison, including Hare. But as he did so, he thought he felt something wobble. ‘Oh no!’ he said to himself, his eyebrows shooting up in panic. ‘My horns – they’re slipping!’

Sure enough. While the horns had looked perfect earlier, what Hare had forgotten was that wax melts. And in the hot morning sun, his elegantly crafted horns were slowly dripping off his head. First he felt a warm drip down his nose.

Then he felt a strange, warm, melting sensation on his head. And then – embarrassment embarrassment of embarrassment – one of his horns fell right off, in full sight of all the antelopes, and yellow wax streamed down his face.

The meeting went quiet. Then everyone started grunting and stamping their feet. ‘Rotten spying Hare!’ snorted Eland. ‘Traitor!’ trumpeted Reedbuck. Together the creatures lowered their horns and stormed the wet, sticky creature, before taking it in turns to pick him up by his short little ears and toss him like a ball from antelope to antelope. When the creature was filthy, and waxy, and a bit bruised, the king trumpeted. ‘I think Hare has learnt his lesson, fellow creatures,’ he said, surveying the hot, waxy animal lying in a ball in the sand. ‘And I trust now his new head ornaments will remind him for ever more that not everything is his business.’

Shamed, and slightly sore, Hare stood up and hopped home. When he saw a waterhole, he stopped to look at his reflection. What he saw horrified him. His horns were gone – but what had happened to his ears? He looked again, thinking his eyes were tricking him, but they hadn’t. On his head were the longest ears he had ever seen – long, fluffy ears that rose from his head straight into the sky. ‘Well at least I will be able to hear well,’ he sighed, and hopped off home.

Hare can hear much better now, thanks to his new ears. But they haven’t really helped him hear any more secrets. For every time a jungle creature sees a hare coming, it remembers to keep its mouth shut. Those big ears are a reminder that a hare is a creature which would like to know everything and will do anything – even make himself horns – to find it out.

Told to me in Ndebele by Monica Khumalo in Bulawayo, Zimbabwe

Once upon a time, the frog was the greatest singer in the animal kingdom. Its voice was sweet, and its songs clear, and animals would travel from faraway lands to hear its recitals on the banks of the river.

In a nearby village lived a great and good chief who was loved throughout the land. His cattle were fat and his villagers had rich supplies of food. Their water was cold and plentiful. And there was peace throughout their land. It was a time of great happiness.

The chief was fond of all his people, but his favourite was his youngest daughter, a sweet, kind and very beautiful young girl. One day the girl and her friend decided to go swimming. It was a hot day, and they walked through the sunny forest until they reached a cool pool. They had never been to this pool before, but it was so leafy overhead, the water was so clear and the banks so grassy that it seemed a perfect place for a swim. Soon they were splashing about, their laughter ringing in the leaves above.

It so happened that this pool was the one in which Frog lived. That day, he was sitting on his favourite lily leaf, warming up his voice for his evening singsong. ‘What a lucky frog I am,’ he hummed happily, ‘to be king of such a cool pool. In fact I’m such a lucky king, I might even start to sing.’ He opened his mouth, stretched his great green throat into the air and prepared for a sensational singsong.

Frog swam through the choppy water, until he reached the surface. Just as he put his head up, another wave came whooshing towards him. This one, too, went straight into his mouth and down into his froggy lungs. ‘Croooooaaaak!’ he spluttered, as his fat body sunk for the second time.‘Croooooaaaaak!’

Frog was extremely unhappy. Every time he tried to raise his head above the water, he got knocked back under. And every time he tried to protest, a strange croaking sound came out of his mouth. ‘Croooooaak,’ it went. ‘Croooooooaaak!’

Tired and half-drowned, Frog swam to the bank and slowly crawled out, shaking the water from his mouth and ears. Once on solid ground, he looked round to see who had dared to dethrone him. There in the pool were two girls, splashing and singing, lurching his lily pad thrones about as they did so.

‘Foolish females,’ he gargled through his water-filled throat. ‘Do you not know that I am King of the cool pool? You must be punished!’ Slowly but surely he puffed and he huffed, until his body was almost double its size. Then, when he was as round as a ball, he opened his secret little poison sacs behind his ears, and blew and blew, until horrible clouds of green noxious gases rose above his head and wafted towards the swimming girls.

The girls’ laughter soon turned to coughs. Then splutters. Then howls as the poisonous gas filled their lungs. And when they could cough or splutter no longer, they both sank beneath the surface to the bottom of the pool.

Later that afternoon, the chief began to get worried. His daughter was normally back before dark. So off he set with his faithful warrior, until he reached the cool pool. Instead of his daughter, all they found was her reed skirt and beaded necklace. And a fat frog sitting on a lily pad.

‘Oh, King of the cool pool, and singer of great songs,’ said the chief. ‘Have you seen my precious daughter? Her skirt is here, and her necklace is here, but her smiling face has gone.’ Being a cowardly fellow, Frog just shook his head and opened his mouth to sing no. But instead of sweet little froggy notes, a terrible croaking noise out of his throat. ‘Naaaaaooooaaaaoooooo,’ he gurgled and croaked, cringing in horror at the awful tones. The chief looked at him suspiciously. ‘That sound, Terrible Toad, is a sure sign of punishment from the gods,’ he said. ‘It is the voice of guilt. And from now on, Man will abhor you. You will be forbidden from singing during the day, and Man will hunt you until the end of your days!’

From that day on, frogs have avoided Man, hopping off their lily pads at the mere sight of one. They are also very sorry for what they have done. Listen carefully at night and you will hear them croaking mournfully from ponds, remembering the great days when they were the kings of the cool pool.

Told to me in English by Gcina Mhlophe, a professional storyteller, in Johannesburg, South Africa

Once, a long time ago, a drought came to the earth. Every day both Man and animals looked up to the sky, praying it would rain, but it never did. The fields became cracked from the fiery sun and the waterholes shrivelled up. Soon there was nothing left on the earth but red hot dust and a couple of puddles.

King Lion got very worried. Some of his subjects had not eaten for weeks. Giraffe’s neck was bonier than ever. Impala had lost the spring in his step. Even the normally fat buffalo’s ribs had started to show through his dusty black coat. Something had to be done.

So the king called a meeting. ‘Animals,’ he roared, as his subjects gathered in the shade of the great fig tree. ‘I have called this meeting because, as you know, we have no food, and if we don’t come up with a plan, we will all soon turn to dust. So, if anyone has an idea, would he please step forward.’

The animals all looked at each other, hoping someone else would come up with a solution. The impalas wagged their tails nervously. Wildebeest stamped their feet and snorted. Zebras hurrumphed and flicked their long black tails. And Elephant rumbled his throat importantly. But no one actually said anything.

Then a tiny nervous voice rose from the antelopes. ‘Excuse me, Your Majesty,’ said Waterbuck, shyly stepping forward to show off his white-ringed bottom. ‘But I have an idea.’

The animals all looked up at the brown and white buck. ‘Well,’ roared Lion, flicking his tail impatiently, ‘what is it? Step forward, step forward!’

Waterbuck, as you know, is a shy, solitary creature, which doesn’t like crowds, so it took great courage for him to pipe up. ‘As you know, King Lion, I usually drink by the river, and down there is a small pool of water and the last patch of green grass in the kingdom. If all of us planted pumpkins and mealies there, that might tide us over until the rains come. We might all then be saved.’

The animals all cheered. What a wonderful idea! King Lion praised Waterbuck, saying ‘If Man can grow crops, why can’t we?’ and at once the animals made hoes and set off for the field. Every animal helped – either ploughing the land, planting seeds or watering them from the tiny pool left in the river. By sunset everyone was exhausted and set off home.

The field was a great source of pride to the creatures, and each day one of them guarded it and watered it. Everything was going well – the mealie plants rising high in the sky and the pumpkins ripening – until one terrible day, when Impala didn’t return from his duty. The animals saw him go to the river, but he never come back. The next week Eland vanished. Then big Buffalo. The animals began to get worried, and soon no one wanted to guard the crops.

So once again King Lion called a meeting. ‘As you know, Animals,’ he growled. ‘Waterbuck’s plan is going extremely well. But a spell has fallen on the field. As fast as our crops grow, our guards vanish. Now no one wants to go to the field and our crops are wilting. We must decide what to do.’

Once again, the animals looked at each other nervously. And again Waterbuck piped up. ‘Your Majesty,’ he stuttered, looking shyly at the King under his long black eyelashes. ‘Being a Waterbuck, I spend much of my time at the water. I usually love water. But I don’t like guarding the water at our field. At night it has red eyes in it!’

‘Red eyes?’ snorted the king, as the rest of the animals started to snigger. ‘How can water have eyes in it, silly Waterbuck? Are you ill? Do you need a doctor? Water doesn’t have eyes!’

Waterbuck was most upset. ‘You animals can laugh,’ he sniffed huffily, ‘but if any one of you will come with me, I will show you.’

The king felt a bit sorry for Waterbuck. After all, he had been brave enough to step forward with an idea. So the king agreed. ‘All right, Waterbuck,’ he said. ‘I will accompany you. We will meet at the pool tonight.’

As agreed, under the light of the moon, Waterbuck met the king. The two of them hid quietly behind some reeds and watched and watched. At first nothing happened. Then, just as Waterbuck had said, the king spotted two huge round eyes in the water. ‘You are right, Waterbuck, you are right!’ whispered the king, looking terrified through the reeds. But, being a brave king, out he stepped and spoke to the eyes: ‘Red eyes, red eyes shining bright, Come out of your water tonight!’ he commanded.

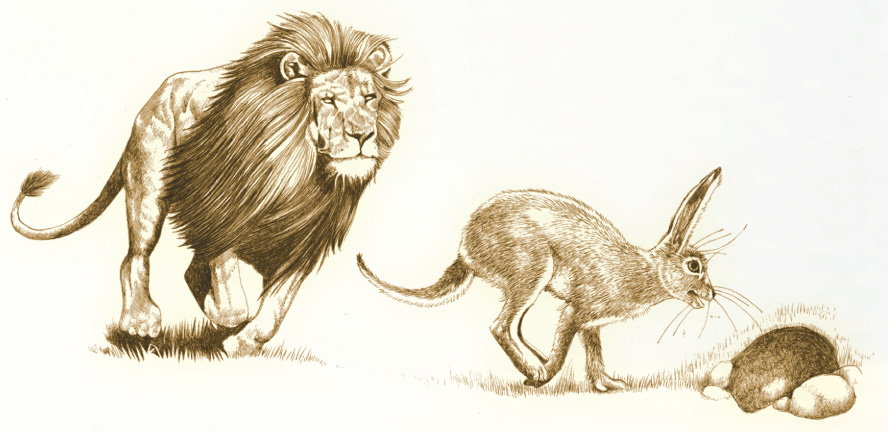

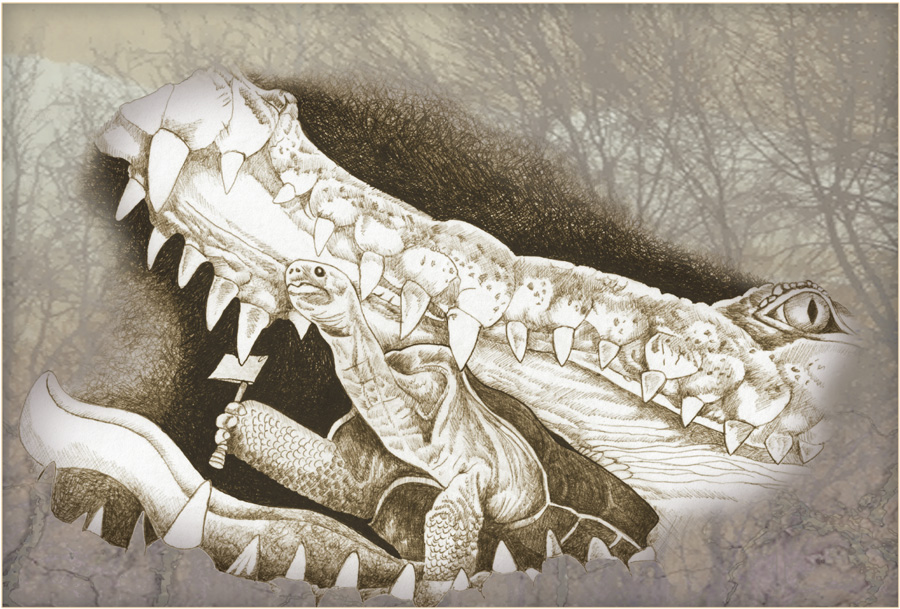

To the pair’s horror, out of the water slid the eyes until soon, under the light of the moon, lay the hugest crocodile anyone had ever seen.

They both trembled. ‘Who, pray, are you?’ said the king in a wobbly voice.

‘Who am I?’ bellowed the creature in a terrifying voice. ‘I am Gongqongqo, King of the Crocodiles. I eat buffaloes whole – horns, hooves and all. I swallow impala as a snack. I have tortoises for my tea! You will be a mere morsel in just one snap, scrawny old lion!’

Waterbuck and Lion shook and quivered. This creature was scary – too scary for even the king to tackle. They looked at each other in terror and, tails between their legs, ran for their life without once looking back.

Back at home, the jungle was woken by the king’s frightened roar. With eyes as large as pools, the normally brave king related in a little trembling voice what he and Waterbuck had met at the field: the biggest, fattest, longest, nastiest crocodile anyone had ever seen.

Impala looked terrified. ‘He said he’d have me as a snack!’ he cried, his little front legs shaking nervously. ‘What will we do?’

Again, the animals were silent, hoping someone bigger and braver would come up with an idea. Then, from the ground, came a little old reedy voice. ‘I’ll get him!’ it squeaked. The creatures looked down, and there on the ground stood Tortoise. ‘Give me a little sharpened axe that I can hide in my shell,’ the creature said, ‘and I will rid you of this pest.’ The animals gave a little giggle. But as no one had a better idea, the king agreed, and soon the animals were waving Tortoise and his little axe goodbye.

When Tortoise got to the field, the enormous green monster was lying sprawled in the moonlight. ‘What are you doing here, you silly snack of a shelled creature?’ it bellowed, spewing rotten fumes from his mouth. ‘Don’t you know I will eat you?’

To the beast’s surprise, Tortoise agreed. ‘Please, oh please eat me,’ Tortoise begged. ‘We are so short of food and water that it would be a pleasure to live in your mouth, great beast. Perhaps, then, I could share in your feasts.’ And he strode straight up to the surprised creature’s mouth and the great beast tossed him back under his great pink tongue.

It was exactly as Tortoise had planned. As soon as he had got to his feet under the creature’s tongue, he pulled out his little axe. ‘We’ll see now, Crocodile, who will eat whom for a snack,’ he giggled. And bit by bit he started to chop away at the great crocodile’s tongue.

No matter how much the creature roared, or tossed its head about in pain and anger, Tortoise continued his job. Chop, chop, chop he went, until at last his job was done. The large crocodile’s tongue fell out into the field, and with it Tortoise jumped out.

The animals, having heard the noise, rushed up to the field and there they found the creature lying tongueless on the ground. ‘From now on, Crocodile,’ said King Lion, standing by the creature’s tongue, ‘you must promise to leave our fields alone. Remember you are a water creature. Try and creep out again and you know what will happen.’ With a scared little grunt, the injured crocodile crept back into his pool and the animals carried Tortoise home to celebrate his great victory.

Since then, crocodiles have rarely been seen in fields again. They are scared of creatures with axes. But if you do ever see one on land, sunbathing or sleeping with its mouth open, take a look. It won’t have a tongue. Thanks to the bravery of the terrific Mr Tortoise.

This is a story of how the earth became like it is. It is not really a traditional story, just an explanation of why things are like they are. Told to me in San by Nxexao Kgimxow in Botswana

Today earth is like a three-storey house. On the top floor live the gods, the sun, the moon and the stars. On the middle floor lives Man, the animals, the rivers and the plants. And on the bottom live the dead, and the gods who are taking care of them. It wasn’t always that way, though. Once upon a time, the earth was flat …

When the earth was young, it was flat and everything lived on the flat brown ground together: the sun, the moon, the stars, and the animals. And everything had its own place to stay. Sun lived in a cave, where it went to sleep at night. Moon lived in a black pot, and let his light out when the gods lifted its lid. And all the animals – the elephants, the lions, the buffaloes, the hippos, the buck and the birds – shared one big house and the gods above fed them and gave them water.

One day the god Mulungu decided to make Man to share the earth with the animals. He took three handfuls of the soft earth and made three people from it: two men and a woman. One of the men was a leper. ‘I have been sent to save you,’ the leper said to the other man and woman. ‘But soon I am going to die. Once you have returned me to Mother Earth, go to the river and get some water. Then give thanks by sprinkling my body with it.’

When he died, the couple did as they were told and sprinkled water on his grave. When they returned the next day, they were amazed to find that instead of a grave there were fields of millet, of maize and of grass. ‘Hurrah!’ they cried. ‘The gods have been great. We have hay to make a house. We have maize and millet to eat. Now we can have a family.’ So they built a hut from soil and grass, made some porridge from the millet, and soon bore some children. Those children had more children. That is how the earth’s first tribe was born.

One day two men went out exploring the flat earth and came to a cave. Usually caves are dark, but from this one came great rays of heat and light. The men were very frightened. ‘What god lives here?’ they asked, with terror in their eyes. While one man ran away, the other went in to look. Slowly he crept inside, shielding his eyes from the hot light, until he reached the back, where he saw a huge ball of fire under a stone. It was the sun. ‘Man, please help me,’ begged the sun, great flames coming from its mouth. ‘A stone fell on me, trapping all my power, and I can’t escape. I will bring you great luck if you do.’ Once the sun had promised he wouldn’t burn the man, the man lifted the stone, and out flew the sun, with bright trails of sparks and black smoke and roaring flames behind it. It flew and flew until it reached the great lake in the sky, where it still lives today. It kept its promise to Man, and every day it brings light and warmth to the earth, in thanks for the day Man set him free.

One day the children were playing on a beach full of stones. ‘Watch out,’ warned an old man walking by. ‘A small stone is as great as a big rock.’ Puzzled, the children looked at him and continued their game. Five minutes later, he returned to see a little pebble whizz through the air and hit a girl hard on the head. As she fell to the ground, the pebble flew up into the sky where it exploded into a ball of light. It was the first star ever. ‘From now on,’ said the old man, ‘every time a little child dies, a star will light up in the sky at night.’ And until today, it has.

In the same tribe lived a man called Machelenga who owned a big pot. This was no ordinary pot, for inside it he kept the moon. Every day, as he went to the fields, he warned his children not to touch it. ‘The child who touches that pot will have terrible luck,’ he said. ‘It is a most magical pot. So keep your hands off.’

But one night, when Machelenga was out in the fields, one of the children decided to have a peek inside. ‘I’ve touched it, I’ve seen it, I’ve smelt that pot, I can tell you right now that it’s not even hot!’ he boastfully said to his friends. With that, he marched up to the big black pot and picked up the lid. Moon was delighted! He was sick of the confines of the little black space, and with a whoosh of white light, he swooped out into the black night.

Out in the fields, the father knew at once what had happened. ‘You wicked children!’ he said, running back to his house. ‘Gather ladders for we must catch it. Quick, quick!’ After such a long time crammed up in a pot, Moon was not very practised at rising in the sky. By the time the children had found ladders, he had risen only to the top of the first mountain. ‘We can catch him, Father, we can catch him!’ shouted the children, racing to the mountains. ‘Just wait!’

The child who had let Moon out was in the biggest hurry, as he knew how much trouble he was going to be in. He climbed as fast as his little legs could carry him until at last he was at the top, with Moon just above his fingertips. ‘I’ve got him, Father, I’ve got him,’ he cried, and leapt from the top of the ladder towards Moon.

Moon, though, was far too bright to be caught again. Just as the child leapt upwards, it rose even higher into the sky. The child’s hands slipped through the air, and he fell slowly onto the steep, rocky mountainside.

The father and mother wept and prayed to Moon to help them to save their child. But it was too late. The child had died. ‘Because of your stupid Moon, we have lost our precious child’, the wife wailed. ‘I am going to live somewhere else where I will never see your Moon again.’ And off she went.

She has never stopped travelling, for wherever she goes Moon follows. And Machelenga has never stopped crying. Whenever it is full moon, listen. You are sure to hear him howling.

When the earth was young, the skies were full of lightning. It would light up the sky day after day, striking down man after man. Every week there was another funeral, until at last the people got angry with God. ‘Every week we have to have a funeral,’ they shouted, ‘and every week we have to provide food and water for the mourners. If you are going to kill us, at least help with the refreshments.’

The god Mulungu apologised for the lightning and promised he would be more helpful in future. ‘Now when I send lightning, I will also send rain for you to drink,’ he said. ‘And I will thunder, too, to bid my own farewells to the dead.’ And ever since, he has.

Told to me in Shona by Cosam Kachembere in Harare, Zimbabwe

In the days when the earth was young, Mvuu, the hippo, was considered to be the most beautiful of all African animals. His large, muscular body was covered with a dark glossy coat. From his head hung a pair of the longest, silkiest ears in the animal kingdom. And from his well-rounded bottom hung the sweetest, shapeliest tail that any animal had ever seen.

Everyone admired Mvuu, from the emerald-coloured sunbirds and naughty monkeys to the mighty King Lion. Across the jungle, as the handsome hippo walked from grassy snack to grassy snack, the creatures would sing out in praise of God’s most beautiful creation. ‘Mister Mvuu, how beautiful are you!’ cried the monkeys from the trees. ‘Mighty Mvuu, how handsome are you!’ roared the lions. ‘Magical Mvuu, we wish we were you!’ sang the sunbirds.

Soon Hippo began to believe that he was, indeed, the most beautiful thing on earth. Every morning, when he went for his dawn drink, he would stand by the river, admiring his own reflection and remind himself of his magnificence. ‘It’s no wonder I’m a jungle obsession,’ he would say vainly, tossing his shiny hair in the morning mist. ‘It’s quite clear that when God wanted perfection, He made me.’

For a while, the other animals put up with Hippo’s vanity because he was such a picture to look at. But soon it began to annoy them – especially when he started to make nasty comments about them. ‘Bad luck about your bulgy eyes,’ he’d say snidely to the chameleon. Or ‘Pity about your warty face,’ he’d remark rudely to the warthog.

The final straw came one day when Hare was passing by. ‘Poor creature,’ said Hippo, as he watched Hare hop. ‘Such a spindly little frame, and such silly floppy ears. And then, the misfortune of such bent-up back legs. The gods must have been crazy when they created him!’

Now, as we all know, hares have very fine hearing, and this one wasn’t at all happy with Hippo’s horrible remarks. ‘He might be beautiful on the outside, but he is turning rather rotten inside,’ muttered the miffed hare. ‘I am going to have to think of a way to sort him out.’ And off he hopped to have a think.

Later that day, Hippo was rather surprised to see Hare carrying large bundles of grass towards his house. ‘What are you doing?’ asked Hippo with a frown. ‘Oh, beautiful Mvuu, I am building a fence just for you,’ replied Hare. ‘Then once you are inside, you won’t get dust on your glossy hide.’

Hippo was very pleased. Hare might be ugly, he thought, but he certainly was clever. That night he wandered happily towards his newly fenced house, knowing that in the morning his coat would be even more beautiful, and even glossier.

Once Hippo was settled for the night, Hare crept off to a nearby village. The villagers were sitting round a fire, entranced by a storyteller’s tale. And, while their attention was on the story, Hare silently crept beside the fire, stole a burning branch and raced off. When he got to Hippo’s new fence, he flung the burning branch onto it and hid behind a nearby tree to watch.

Flames soon flickered skyward, setting fire to everything in their path, including Hippo. ‘Help! Help!’ cried the mighty Mvuu, as the flames leapt on to his precious coat. ‘My ears! My tail! My neck! My face! Help me, oh help me get out of this place!’

Hippo was not a fast runner in those days, but with such scorching flames searing his flesh, the fat creature was soon racing down to the river at the speed of a cross crocodile. When he got there, he jumped in with a mighty splash, and stayed underwater while the cool, wet water soothed his sore, blistered skin.

Mvuu stayed in the water all night, until dawn, when at last he started to feel better. The pain had died down. His tail had stopped throbbing. And even his big bottom had stopped burning. Slowly, he raised his big belly from the river bed, and blowing bubbles, floated up to the surface. Then he got out of the water, and took his normal position on the riverbank, where there was a great pool of water to admire himself in.

But what a shock he got! Rather than the gorgeous, glossy, graceful Mvuu he had been, the creature in the reflection was a stumpy, rather ugly, animal, with no hair at all. Gone was his beautiful, glossy coat. In the place of his long ears were two stubby lumps. At the top of his bottom was a tiny, stubby, fat little tail. His body was covered with a thick, grey skin, with rather nasty patches of pink where the flames had burnt deep.

With a miserable snort, Mvuu threw himself into the river. And there he has remained ever since, coming out only at night when the other animals can’t see him. Occasionally, you’ll hear him weep when he sees other animals come to admire their own reflections. If you listen carefully, you’ll hear him.

‘Boooohuhuhuhu,’ he’ll cry mournfully, ‘Boooohuhuhuhu.’

Told to me in Shona by Cecilia Masekereya in Mabvuku, Zimbabwe

Long ago, there was a drought. There was no fruit on the trees. The green grass turned brown and died. Even the sausage tree stopped making its delicious long green sausage pods. There was nothing on the ground to eat but stones and dust.

The animals were so hungry that King Lion decided to call a meeting. ‘Someone has to have an idea what we can do,’ he said. So, one day, all of the animals gathered under the shade of the acacia tree. Most of them had never seen a drought, so didn’t know what to do. Others, like Elephant, had seen several – when food didn’t grow the whole year and rain only fell twice during summer. So it was to them that the animals turned.

‘Nzou, Nzou, what should we do?’ they sang to the elephants. ‘The rain has not come, there are no clouds in the sky, the only thing left is to lie down and die.’

The elephants, being clever creatures, didn’t stand for silly sentimentality. ‘What nonsense, foolish fellows,’ trumpeted the enormous bull elephant. ‘We will have to do what Man does. When he can’t find food, he grows it.’

The animals erupted in a mass of disdainful bellows and howls. ‘Grow it?’ growled Leopard, prowling up and down in disbelief. ‘Plough fields?’ howled Hyena, cackling with laughter. ‘Sow seeds?’ giggled Gnu, tossing his mangy fringe.

But King Lion gave a roar. ‘If any animal has got a better idea, would he step forward?’ he said. Slowly the noise subsided and the stamping stopped, as the animals hung their heads in shame. After a few minutes of silence, the king spoke again. ‘Well, Elephant,’ he smiled. ‘I think you’d better tell us how to do it then.’

Elephant, rather pleased with himself, flicked his trunk into the air and strolled self-importantly to the front of the crowd. When the last giggles and chatters stopped, he began. ‘I have seen Man,’ he droned, giving an elderly snort every now and then, ‘and what he does is this. He clears the bush, then he ploughs, then he sows, then he waters, he weeds and he reaps. He plants a variety of plants, so he has some ready in weeks, while others are still ripening. That way, he has food all summer.’

The animals listened and, when he’d finished, let out a loud cheer and quickly arranged themselves into the groups he ordered: rhinos to clear the bush, buffaloes to pull the plough, baboons to plant the tiny seeds, antelopes to pull up the damaging weeds and elephants to sprinkle little pools of muddy water onto the plants to make them grow. After just one meeting, the animal kingdom was going to become one big animal farm.

The animals worked hard, ploughing and hoeing and weeding and reaping and soon the jungle was a mass of lush, green fields filled with delicious crops. There were golden mealies, fat sweet potatoes, crisp green cabbage and bulging orange pumpkins, which the animals ate for breakfast, lunch and supper. Soon everyone fattened out, coats became glossy again, and mothers began to have plump, happy babies.

Life was great in the jungle until the terrible day Hare went to collect some maize and it wasn’t there. Every single maize cob had been stolen and the stalks stood bare. The next day, the turnips were taken.

And the following day the sweet potatoes were stolen. The animals were furious – especially Hare, who had stood guard on the night the turnips had vanished. ‘What can I do,’ he wondered, ‘to catch the thief who is pinching our food?’

All night he tossed and he turned in his burrow, trying to think of a plan to catch the thief. Just as dawn broke, he came up with an idea. ‘I know!’ he said, hopping up and down in his burrow with glee. ‘The pumpkin!’

In the middle of the main field, the animals had grown the most magnificent orange pumpkin. It was large and golden and would be ripe within days. ‘It would be a perfect trap for a thief,’ Hare decided.

After cutting a small trapdoor and hollowing it out, Hare climbed into the pumpkin. ‘He will not be able to resist this,’ he smiled, as he sat inside and waited.

Sure enough, once the sun had set, and Owl started twittering and whoooooing, Hare heard footsteps outside the pumpkin. ‘It’s the thief,’ he thought, giggling nervously. It was. But before Hare had time to jump out and attack the creature, the whole pumpkin, with him inside, was put in the creature’s big mouth and swallowed.

‘Hey, hey, help!’ shouted Hare, as he and the pumpkin slid down into the creature’s belly. ‘Stop thief, stop!’

The creature, terrified of the noise it heard, started running away in panic. But everywhere he went, the noise went too. If he jumped across a river, the noise jumped too. If he climbed a tree, the noise climbed as well. Even when he went home to his wife, the noise went home with him.

The creature was terrified. ‘What must I do?’ he cried to his cowering wife. ‘I’ve got a devil in my belly!’ But his wife had no time to answer, for from the depths of its belly came a dark voice: ‘Take me to your king oh thief, or you will get no sleep, take me to your king, oh thief, or I will make you weep!’ And from inside its stomach came a thudding and bumping noise as Hare took his fists and punched and thumped.

The creature howled in terror and hollered in pain, until at last he could bear it no more. ‘I promise, I promise to take you to the king,’ he cried, and he ran as fast as he could all the way to Lion.

When they got there, the creature spoke. ‘Oh dear King, help me,’ he moaned, holding his tummy. ‘Inside my stomach is a voice. It hurts me and it devils me. I have to get it out!’

Before the king had a chance to answer, a voice rose from the creature’s stomach. ‘King, I am no devil. If you order this creature to open its mouth, you will see who I am when I climb out.’ Amazed, the king ordered the creature to do as his tummy had told him. And, sure enough, out of the creature’s big mouth scrambled not a devil, but a very wet, pumpkin-covered Hare.

When Hare had wiped all the pumpkin from his face, and opened his eyes, he couldn’t believe what he saw. ‘Baboon!’ Hare exclaimed, staring at the creature who had eaten him. ‘You rotten thief!’ Rather shamefaced, Baboon admitted that it was he who had stolen not only the pumpkin, but the animals’ other crops as well.

After praising Hare for his marvellous thief-catching trick, the king turned to Baboon. ‘You have proved to be a lazy and wicked creature who has tricked your hard-working friends,’ the king scolded. ‘For that, the animals can never forgive you. You must take to the hills for ever.’

Sadly, Baboon walked through the valley and climbed high up on to a hill to live. He has lived there ever since. He occasionally ventures into the valley to steal a cob of maize or a juicy sweet potato from someone’s field. But there is one thing he will never, ever steal again: pumpkin. I think you know why.

Told to me in Tonga by Beatrice Shawalala outside Lusaka, Zambia

Many years ago, two men set off on a long journey to a faraway valley. All day they travelled, walking over sharp rocks and swimming through streams, climbing over fallen tree trunks and wading through sharp reeds.

It was a hard journey, and by sunset both men were exhausted, hungry and thirsty. It was also getting dark and they had nowhere to sleep. But at last, they spotted a village: a cluster of thatched huts, a well for water and – even better – a fire with a cooking pot steaming on it.

As they walked towards the village, the chief, in leopard skin pants, came out to greet them. ‘Welcome!’ he said, smiling. ‘You must be hungry – come and eat. You must be thirsty – come and drink. And, please, stay the night. However, you must make one promise.’

The men nodded. ‘Of course we will make a promise. What is it?’ The chief looked at them with a serious face. ‘We will happily give you food, water and a bed for the night. But you must promise not to snore. We are very busy people who need our sleep. So anyone who snores is punished.’

The men both nodded their heads in agreement, then sat down round the fire for a meal of maize meal, chicken and beer. It was a fine feast, and after it, the old villagers gathered round the fire to tell stories – tales of wild animals, hunting trips, brave warriors and wise chiefs. Eventually, when the moon was high in the sky, the men went to their hut and settled down to sleep.

In the middle of the night, one of the men woke up with a terrible fright. There was something in the hut – something that was making a loud roaring, whistling, blowing sound. A terrifying sound! He lay there with his heart beating in his chest and raised his head slowly to look around. There was nothing in the hut but his friend. Yet still the noise rose in the air. ‘Nnnnnnnkkkkkkkkhhhho!’ it went loudly in the darkness, ‘Nnnnnnkkkkkkkkkkho!’ As the man looked round the hut, he realised what the noise was. ‘Oh no!’ he exclaimed in the dark. ‘My friend is snoring! The chief warned us that anyone who snored would be punished. I must get up and stop him.’

Quickly he rose from his bed to wake his friend, but it was too late. Outside the door he could hear the villagers whispering about the terrible snoring and the punishment the chief was going to inflict.

Before anyone had had a chance to come inside the hut, the man had made a plan. He started to sing.

Slowly, the villagers’ whispering stopped and another sound started – the villagers singing along. They sang and they sang. They fetched their drums, then their whistles. And before long the man could hardly hear his own voice for the party outside. All night the villagers sang and whistled and danced. At last, when dawn came, they all went to bed, tired but happy.

That morning, the snoring man woke up refreshed after a good night’s sleep. His friend, however, was exhausted. ‘You have no idea how lucky you are that I saved you!’ said the tired friend. ‘We can’t stay here a single night longer, though, for this time the villagers will surely punish us.’

After breakfast, the men packed their bags and went to thank the chief for his hospitality. ‘No, no, no,’ said the chief, smiling. ‘It is we who must thank you. For never before have we heard such sweet songs, or held such a marvellous party. Please, as a thank you, take this gift of gold.’ The chief then handed the singing man a leather bag filled with shiny, precious gold.

The two men couldn’t believe their luck, and once they had thanked the chief again, they set off on their journey. But as soon as they were out of the village, the snoring man asked his friend to stop. ‘I would like my share of the gold now,’ he said. ‘Let’s stop under this shady tree and divide it.’

The singing man was not only tired from having been awake all night, but he was very grumpy. ‘What do you mean divide it?’ he said crossly to the snoring man. ‘If I hadn’t sung all night, and whistled and danced and entertained those villagers, they would have had us for supper. All you did is make horrible snoring sounds. It was you who got us into trouble in the first place.’

The snoring man shook his head vigorously and started to shout and wave his fist about. He’d had a good night’s sleep and was now full of energy. ‘Listen here,’ he said, waving his finger at his tired friend’s face. ‘If it weren’t for my snoring, you wouldn’t have had to sing in the first place. You would have slept all night. It’s thanks to me that you were given the chance to entertain the villagers. Half that gold is mine. Now hand it over!’

No matter how hard the snoring man tugged, the singing man wouldn’t hand over the bag. Soon the former friends were wrestling in the mud, pounding and punching and hitting each other.

What they didn’t realise is that they were being watched from above. The rain god happened to be passing on his rain clouds in the sky, and he couldn’t believe how silly the two men were being. After thundering loudly at the men from above, he shot down a huge bolt of lighting. With a crack! and a bang! it sent the pair whizzing into the air. And with a fizzz! it hit the bag of gold, shooting it like a star into the sky.

Neither of the men ever saw the gold again. The rain god took every little bit and used it to make his rainbow sparkle. But that doesn’t stop men from trying to find it. Every time it rains, you will see them heading across the Mrican valley towards the rainbow. Ask them where they are going and they will tell you – to find the singing man’s lost bag of gold.

Told to me in Ndebele by Isaac Nyatha in Bulawayo, Zimbabwe

The honeybird has always been the friendliest of birds, fetching men from their fields and leading them into the forest to show them where to find honey. ‘Chee Chee!’ it has called for centuries, ‘Follow me! Follow me!’ flying in circles around the spot where man could find sweet, golden honeycomb.

One day, long ago, Honeybird found a very large honeycomb that his friends the bees had been working on in the hollow trunk of a tree. He loved honey, but being a kind, sharing creature, he flew straight to the fields to find someone to share his good fortune. At the edge of the forest, in a little clearing, he saw a man busily planting maize seeds in the earth. ‘Chee! Chee!’ sang Honeybird, flying backwards and forwards over the man’s head. ‘Chee! Chee! Follow me! Follow me!’

The man had heard of the great honeybird, which led lucky men to a kingdom filled with sweet golden treasure, but he had never seen one with his own eyes. So, quickly, he lay down his spade and seed and followed the bird into the forest.

The man climbed down ditches, over tree trunks and through rivers until at last the bird stopped before a hollow tree where a swarm of bees lived. There, it flew round and round, darting up and down, directing the man exactly where to look.

Staring into the tree, the man couldn’t believe his luck. For there, in the dark hollow, was the biggest stash of honey he had ever seen – great layers of golden, dripping combs that overflowed from the trunk and permeating the air with a sweet, flowery smell.

The man was ecstatic, and being rather a greedy chap, he quickly fell to his knees, stretched his hand inside the hole and took out a great big piece of comb, which he stuffed into his mouth. With honey dripping down his chin and running down his arms, he took another, then another, chomping and chewing and slurping and swallowing, until soon there was not a single drop of honey left. After a very noisy burp, he got up, wiped his sticky hands on his trousers and set off, without even bothering to thank the bees, or his guide the honeybird.

Honeybird was furious. ‘Chee Chee!’ he squawked unhappily after the greedy, rude man. ‘Chee Chee! What about me? What about me?’ But the man didn’t even look up as he rubbed his rounded belly and headed home.

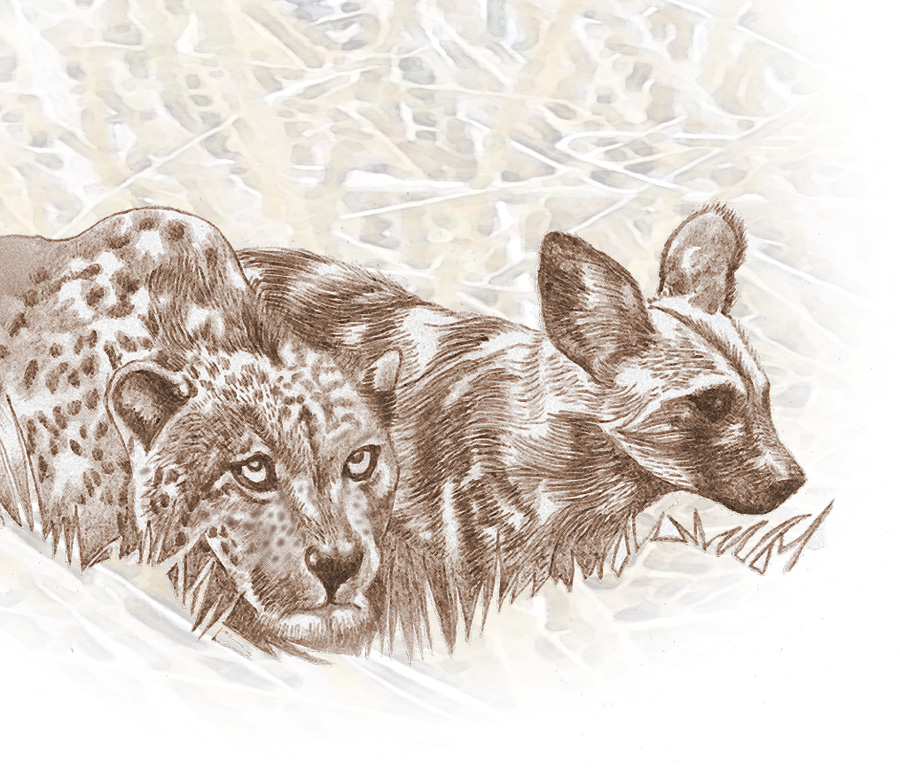

The next morning Honeybird was still so cross about the man’s ingratitude that he had an idea that might teach the man a lesson. Flying through the forest, he looked here and looked there until he found exactly what he wanted. There, under a fallen tree in the middle of the forest lay a leopard with her three cubs. Not only was their home shady and protected, but nearby was a supply of dark, rich honey. And, as you probably know, leopards like nothing more than a daily lick of honey.

Once he’d hatched his plan, Honeybird knew exactly what to do: to fly back to the man’s field and lure him once again. The man of course was over the moon, for although he was feeling a little sick from too much honey the day before, he couldn’t resist the cry. Quickly, he threw down his tools and hurried after the bird.

The journey to the honey was longer this time – over a river, around a hill, through a thick forest and down a narrow path – but at last Honeybird stopped flying, and began to circle a thickly grassed area. Knowing that meant honey, the man greedily shot forward, his legs stumbling in the grass to get to the fallen tree.

This time, though, there was more than just golden honey waiting for him. Leopard had spotted the fat-tummied human stumbling through the bush from far away, and as the man clumsily stepped on one of her cubs, Leopard leapt forward with a terrifying roar.

With one swipe of her paw, she swatted the man to the ground and bit him hard on the arm. It was not a nice lesson to learn, but Man knows now. Today, whenever he is invited into the animal kingdom, he enters with caution, knowing that the treasures of the forest are for all – creatures great and small.

Told to me in Bemba by John Zulu in the Luangwa Valley, Zambia

One morning Tortoise was ambling happily towards the river when he came upon Hare. He wasn’t particularly pleased, for he had always thought Hare was rude. But today he was even less pleased than usual by the long-eared creature’s snide greeting. ‘Morning slowcoach,’ sneered Hare, nibbling casually on a piece of grass. ‘Can I give you a lift to the river? I would hate you to miss sunset …’

Tortoise narrowed his eyes crossly. ‘Actually, Hare,’ he said, in a stiff, unamused tone, ‘it is I who should be offering you a lift. As every intelligent animal knows, tortoises are fine athletes, particularly over long distances. Even a supposed slowcoach like me could outrun a mere bunny like you.’

Hare laughed. Run? He had never seen Tortoise even jog! But as the creature was so cheeky, there was only one way to find out. ‘Well, old man,’ he said, ‘what about a race?’

Tortoise grinned. Hare had fallen into his trap, and he had planned exactly how he was going to win the race. ‘Give me a few days to train,’ he said, ‘and I will be ready. Shall we say Saturday?’ With the date set, Hare hopped off happily.

When Hare was out of sight, Tortoise called his relatives together and told them about the Saturday’s race. ‘If you want to teach that conceited creature a lesson, you will all have to play a part,’ he said.

‘Listen carefully, for this is what I want you to do …’ Carefully he explained how each tortoise should hide in bushes along the route of the race, and come out when he was needed. ‘We all look the same,’ he grinned. ‘Hare will never know that you are not me!’

On the day of the race, Hare and Tortoise met under a shady marula tree, watched by a crowd of excited animals. As the pair lined up at the starting post, Fish Eagle gave a screech. ‘Go!’ he whistled through his sharp yellow beak. ‘Run!’

The two creatures ran as fast as their legs would carry them, Hare leaping off, with Tortoise trundling along behind him. After a while Hare became thirsty. ‘Given I can’t see Slowcoach for dust, I might as well sit for a sip and a snooze,’ he said, with a self-satisfied smirk. Stopping, he settled down beneath a shady tree with a calabash of water and soon went to sleep.

After a few minutes, he was awoken by a yell. ‘Hey, Long-ears. Bit tired?’ he heard. As he opened his eyes, there was Tortoise, jogging freshly along in front of him.

Hare couldn’t believe his eyes. How on earth had old short-legs managed to catch up, he wondered. Jumping up with his calabash, he leapt off again, overtaking Tortoise and hopping and jumping as fast as his legs would take him.

He hopped and hopped and hopped, but with the sun beating down on his back, and dust flying into his face, he soon needed to stop. In the shade of a tree, he uncorked his calabash and lifted it to his mouth. But no sooner had he had a single gulp than a yell passed by. ‘See you at the finish, Hare!’ shouted a voice. Hare couldn’t believe his ears, so he lowered his calabash and looked with his eyes. His ears weren’t tricking him. The brown flash was indeed Tortoise!

Panicking, Hare leapt up and was soon hopping and leaping over logs and through grass. At last he saw the long, green river – where the finish line had been set. ‘Thank goodness for that!’ he sighed, as little beads of sweat slipped from his fur. ‘The end!’

He slowed down, and closing his eyes imagined the medal being put round his neck and the animal kingdom gathering round to offer their congratulations. ‘How wonderful it will be,’ he smiled, ‘to be the fastest jumper in the jungle!’ But as he looked forward his heart sank. For just before the finish line, about to cross it, was Tortoise.

A roar went up from the watching crowd of animals and the skies were filled with happy cries and shrieks and howls and yowls as Tortoise slowly crossed the line. ‘Well done, Shelled One!’ yelled Giraffe, waving his neck about excitedly. ‘King of the Road!’ trumpeted Elephant, stamping his feet till dust rose in the sky.

As Tortoise was patted on his shell and a medal hung about his scaly neck, Hare had to admit he had been well and truly beaten. ‘You have talents, Tortoise, that I had never imagined,’ he said shamefacedly, his ears flopping down with embarrassment. ‘From this day forward, I will never tease you again.’

The Tortoise looked at him, smiling wisely. ‘My relatives and I are delighted to hear it, Hare,’ he said. And off he went for a great celebration – of the greatest tortoise relay team that ever lived.

Told to me in Shona by Mason Kanjanda in Harare, Zimbabwe

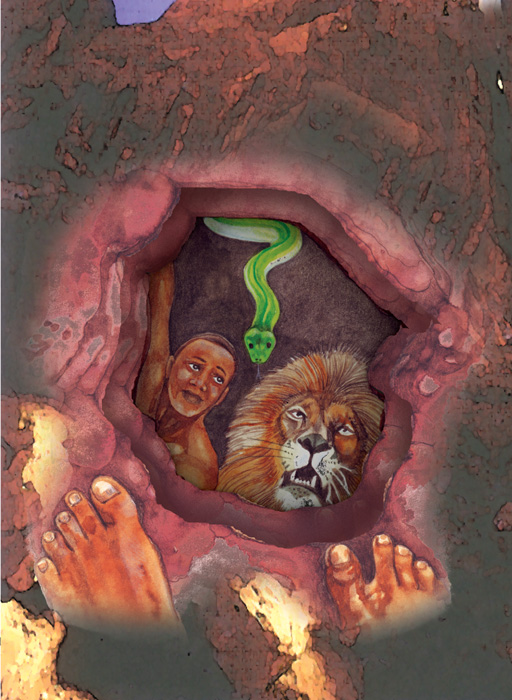

One day, long ago, birds flying over the palace of Zimbabwe heard a beautiful girl’s voice rising in the sky. Her song was sweet, but it was also sad. ‘Help me oh Moon God to be brave; for I have to go to the python’s cave,’ the song went.

The birds looked over the stone wall of the king’s palace and there they saw their friend, the Buhera Princess, weeping in the sun. ‘What is wrong,’ the birds asked. ‘My father is very ill, and we have tried everything to make him well,’ she replied. ‘The most famous witch doctors have come from all over the kingdom, we have sacrificed cows to the Moon God and our ancestors’ spirits, and we have piled our altars with maize and melons. But nothing has worked. Now, my brothers say, I have to go to visit the great python in the cave to beg him to heal my father, the king. They have already been to the snake and returned with nothing but fear. I am the last hope.’

The birds twittered with horror. The python’s cave! Every creature knew what happened in that dark black hole. Things went in, but never came out. How was a young, beautiful princess going to succeed when so many other strong men had failed?

‘No, no, no, you can’t go!’ they shrieked. But the Princess was insistent. ‘My heart has so much love for my father that it has no space for fear,’ she said. ‘I must.’ And down the path she walked, singing with the birds to give her courage.

After a long walk in the sun the princess reached the creature’s cave. Nervously she peered inside until she saw a great black head with yellow eyes shining out. ‘Who interrupts my s-s-s-s-s-sleep?’ hissed the python, its fangs glistening in the sunlight. ‘Do you not know, Princess-s-s-s-s, that my favourite food is people? Can you not see footprints-s-s-s in the s-s-s-sand of brave warriors who have fled?’

The princess looked at the scaly creature with tears in her eyes.‘Please, mighty Python,’ she cried. ‘My father, the king, is dying. Only you, the great healer, can make him well. I beg of you, on behalf of our kingdom, save him.’

The python looked at her through his narrow yellow eyes. ‘S-s-s-s-sing to me,’ he hissed, ‘and carry me coiled round your body to your father. Your s-s-s-sweet voice will be my payment.’

The birds, sitting in the trees, started to screech and cry. ‘Don’t listen, Princess, don’t listen!’ they shrieked. ‘That’s how he kills people, by coiling round them and squeezing them to death. Run!’

But the princess stood tall as she had been taught by her father, her eland cloak round her shoulders and her gold and ostrich necklace glinting in the sun. ‘Come, Magic One,’ she said, ‘Come.’ Slowly the great snake started to slither out of his cave and wind his long, slippery body round hers, until the princess was completely entwined by cold python skin.

When they saw the python coming, the villagers ran away in fear, until they heard the princess’s sweet voice. ‘Loosen your arrows, and drop your bows,’ she commanded, as the warriors came towards her. ‘I bring a great serpent to heal the sick king.’

But the princess stood tall as she had been taught by her father, her eland cloak round her shoulders and her gold and ostrich necklace glinting in the sun. ‘Come, Magic One,’ she said, ‘Come.’ Slowly the great snake started to slither out of his cave and wind his long, slippery body round hers, until the princess was completely entwined by cold python skin.

When they saw the python coming, the villagers ran away in fear, until they heard the princess’s sweet voice. ‘Loosen your arrows, and drop your bows,’ she commanded, as the warriors came towards her. ‘I bring a great serpent to heal the sick king.’

The warriors did as she said and the python uncoiled itself from her body and slithered into her father’s house. Soon the palace was filled with smoke and smells and herbs, as the princess made a fire and brought out Python’s amulets of healing oils and herbs so that he could make his potion. When a powerful smoke filled the air, the serpent took the mixture off the fire and spoon by spoon fed it the king. Mter twelve spoonfuls, the king sat up. Then slowly he got out of bed and walked. He was healed.

The village erupted as the villagers sang, whistled and shrieked praises to the python. The king fell to his knees before the great serpent. ‘You have saved me,’ he said, ‘and in thanks I would like you to live among us as our Royal Village Healer. Will you stay?’

Python shook his head. ‘I am a creature of the jungle and my place is my cave,’ he hissed. ‘The princess must now take me back.’ Quietness once again descended on the village as the snake wound itself again about her tiny body. Then, with his head resting on her shoulder, they set off into the jungle, her voice rising into the air as she sang songs of praise to the python.

At the cave, the serpent unwound itself. Then, turning to the princess, it invited her in. ‘No, no, no!’ screeched the birds overhead. ‘He will squeeze you, he will squish you, he will bite you and eat you!’ But the princess ignored them. ‘You have saved my father, so I am sure youwill not harm me, dear friend. Thank you,’ she said, and followed him into the darkness.

The cave was nothing like she had expected. Rather than a dark hole littered with warriors’ skulls and bones, with bats flying about, the cave glistened with treasure. Great clay pots spilled jewels out on to rocks. Gold beads lay on the floor. Eland skins hung on the walls. And on a ledge lay a finely beaded wrap of silk.

Python looked at her fondly. ‘You have shown the kindness and strength of a great woman,’ he hissed. ‘Please, take what you like. What is mine is yours.’ Hanging her head shyly, the girl replied as the queen had taught her. ‘Thank you Python,’ she said politely, ‘but I can only accept a single gift. And that must be chosen by you.’