Told to me in Bemba by a leper, Costa Chibilikita, at the Latete leper colony in Zambia and in Bemba by David Siame in Fringilla, Zambia

There was a time when, although Tortoise was very small, he had a very high opinion of himself. ‘I am the strongest creature in the kingdom,’ he would boast to whoever would listen. ‘No one else in the jungle is as powerful as me.’

In the beginning, most animals just ignored the little creature’s idle boasts. But soon the big boys began to get irritated – especially Elephant and Hippo, who, as we all know, are the strongest animals in the jungle. ‘How could such a weak little creature think he is as powerful as us?’ they harrumphed. ‘Who does that scaly little longnecked shell think he is?’ And off they snorted, and stamped and trumpeted, just to prove to the jungle what big fellows they were.

The little Quelea, who was a nosy little bird with a red bill, heard the earth shake and the trees fall as the big boys stomped about, and immediately flew off to warn Tortoise. ‘I would keep right out of the way of Elephant and Hippo,’ he chirruped and chirped, hopping in the trees about Tortoise’s head. ‘They’re in a bad mood, Tortoise, and if you don’t watch it, they’ll squash you flat with one of their big flat front feet.’

But Tortoise just smiled to himself. ‘I’ll show them all,’ he said, a wide smile breaking out on his brown scaly face. ‘I will show them what strength is.’

First thing the next morning, Tortoise stretched his long head and legs out of his shell, nibbled on a bit of dewy grass for breakfast, and started the long trundle to find Elephant. It took a while, as tortoises aren’t the speediest of creatures, but at last he found the mighty Elephant nibbling fresh acacia leaves in the forest.

‘Greetings Mr Elephant,’ he shouted up in the loudest voice he could muster. ‘If you don’t mind, I want to talk to you.’ Elephant couldn’t believe his big grey ears. ‘You want to talk to me!’ he trumpeted at the little creature in astonishment. ‘Why, yes, in fact I do, Mr Elephant. I think we have something to discuss. A little bird told me that you believe I am not as strong as you. And I think you are wrong. In fact, I believe that equals like us should stick together and be friends.’

Elephant was so taken aback by the creature’s cheek that soon he began to see the funny side. ‘You! Mr Tortoise! You think you are as strong as the rock of the jungle?’ he cried, rocking with laughter. ‘And how are you going to prove that, you skinny-legged reptile?’

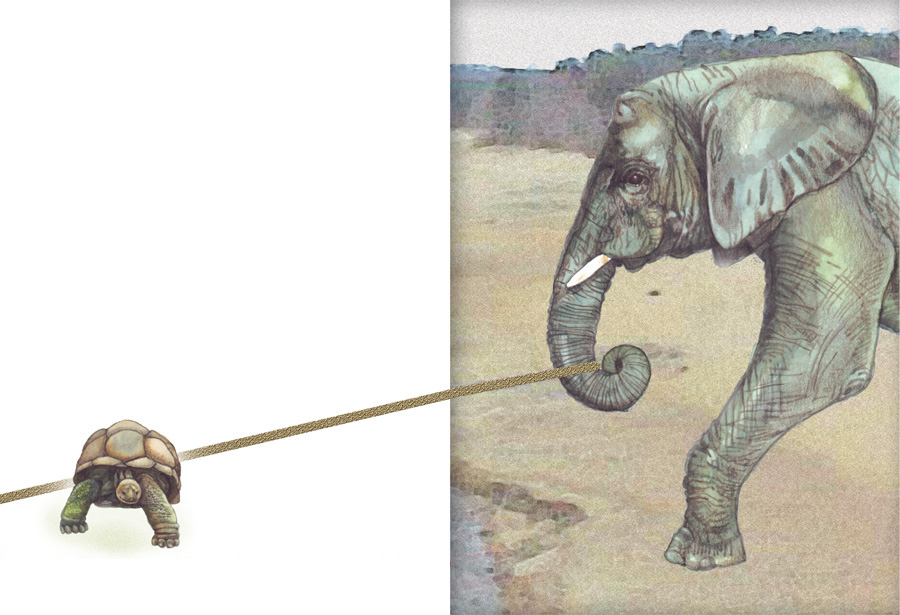

‘Well,’ said Tortoise, a bit put out. ‘I thought that perhaps we might have a tug of war. If either of us can pull the other from his place, he is the most powerful. If neither of us can manage it, we must agree that we are equals.’

Elephant thought it was rather a foolish idea. As everyone knew, he could pull Tortoise into the air with just one tug. But, to settle the matter, he agreed. ‘Right, tomorrow it is,’ he said, as Tortoise handed him the end of a very long vine. ‘But you’d better hold on tight to your end, Tortoise, for tomorrow I am going to make you fly!’

Tortoise then set off to see Hippo, who was cooling off in a shallow pool. ‘Hello Mr Hippo,’ he said, as Hippo opened one eye above the water. ‘I was just wondering whether you could help out with something. Would you agree that I am stronger than you?’ Hippo thought he was hearing things. ‘How can you think you are as strong as I, the Water Cow?’ he snorted furiously, blowing big bubbles from his nose. ‘Get away, you silly creature, before I toss you into the air with one of my teeth!’ With that, he gave a grunt, and disappeared crossly underwater.

Ten minutes later, when Hippo surfaced again, Tortoise was still there. He couldn’t believe the little creature’s cheek. ‘Are you deaf as well as stupid?’ grunted Hippo with a nasty glint in his eye. ‘Which part of ‘‘go away’’ do you not understand?’

‘Well,’ said Tortoise, marching up to the river creature, his head held high. ‘It’s just that the rest of the animals have all agreed with me that I am stronger than you. And I just thought it would be a good chance for you to prove them wrong. But if you don’t want to, fine!’ And off he stamped.

Hippo couldn’t believe his stumpy little ears. How could the animals believe that that timid Tortoise was stronger than him? So he called Tortoise back. ‘If that’s how you want it, fine!’ he snorted. ‘But I’m warning you, Tortoise: I am still going to toss you into the air with my teeth once I have pulled you over here.’ Timidly, Tortoise gave him his end of the vine and agreed that tomorrow, when Tortoise tugged on his end of the vine, Hippo would tug too.

Early the next morning Tortoise went to the centre of the vine and started to shake it. And, just as he had predicted, Elephant began to pull on his end. Then five seconds later Hippo started. Tortoise was delighted. ‘My trick has worked, my trick has worked! What a clever Tortoise I am!’ he sang, waving his stumpy legs in the air. ‘Now we’ll see what strength is.’

All day the two enormous animals pulled. As morning turned to afternoon, they got increasingly tired and sweaty. But neither would give up. Elephant pulled and puffed, as the vine twisted round his stretching trunk. And Hippo heaved and huffed, tugging hard on the vine twisted around his tooth. But neither would consider letting Tortoise win.

After a while, Tortoise began to feel sorry for the beasts. It was a hot day and they must both be exhausted. So, taking a knife, he walked to the centre of the vine and, with a little slash, cut it in two. From one end of the jungle came an almighty crash. And from the other end, rose an almighty splash. Oh, how hard those animals must have fallen, he giggled.

Running as fast as his little legs would take him Tortoise went first to visit Elephant, who had fallen on his back, his trunk twisted and blue from pulling so hard. ‘Why Tortoise,’ Elephant whimpered, as he tried to raise his great, grey body off the ground. ‘I had no idea you were as strong as you are. I apologise for my rudeness. From now on, consider yourself my equal.’ And he put out his battered trunk in friendship.

Tortoise shook his trunk happily, then marched over to the pool to see Hippo. Usually the creature was lazily poking an eye out of the water, but this time, he was floating on its surface, exhausted, with one of his huge teeth missing. ‘My thear Thorthoise,’ said Hippo, lisping through the gap where his tooth was. ‘I am tho thorry I was tho rude. Pleath leths be frienths.’ And he slowly swam out to offer a fat paw to Tortoise.

Tortoise, of course, was delighted his trick had worked and, congratulating himself on his powers, he marched off into the jungle as the word spread about his incredible powers. He has never had a day’s trouble from any beast of the jungle. But if you ask him how he did it he has only one thing to say: ‘Strength is not in the arm, but in the head, dear creatures. In the head.’ And he’s right. Often in life it is not the strength of a creature’s brawn that matters. It is the cunning of his brain.

Told to me in Shona by Sabina Sinjere in Mabvuku, Zimbabwe

Hen, the fattest of the kraal chickens, was bored. Her life was always the same, she sighed: scratching at dry red soil, peck-peck-pecking at corn seeds, flapping around her little yellow chicks and putting up with the loud, bumptious cock-a-doodle-doing of her bossy old husband, the kraal rooster. What she needed was an adventure. ‘Today,’ she decided, ‘I am going to take myself off on safari. It’s about time I escaped this kraal and saw the world.’

So one afternoon after she’d tucked her little chicks up for their nap under a nearby acacia tree, she evaded the sharp eye of her rooster husband, and giving her feathers a quick powdering in the soft rusty dust by the chief’s hut, Hen set off down the kraal path towards the river. The riverbank, according to her friend, Goat, was brimming with exotic creatures: kingfishers with emerald wings, silver fish that could leap over rocks, and beetles that could roll dung balls bigger than their own bodies. This was going to be a day that the kraal hen would never forget!

Hen set out full of the joys of Africa. The sun had turned the afternoon golden with its rays, the msasa trees gently shaded her with their limy leaves, and soon she could smell the weedy, watery, willowy, wet wafts of the river in the wind.

Hen had never been on safari, so once she’d got to the riverbank, she wasn’t quite sure what to do. ‘I know – I’ll have a drink,’ she clucked, scuttling her plump body down to the water.

It all seemed so peaceful, with the river flowing gently by, Mr Kingfisher sitting on a dry branch watching out for fish, and the sun gently glimmering on the water. The only thing that moved in the midday sun was a log gently floating by.

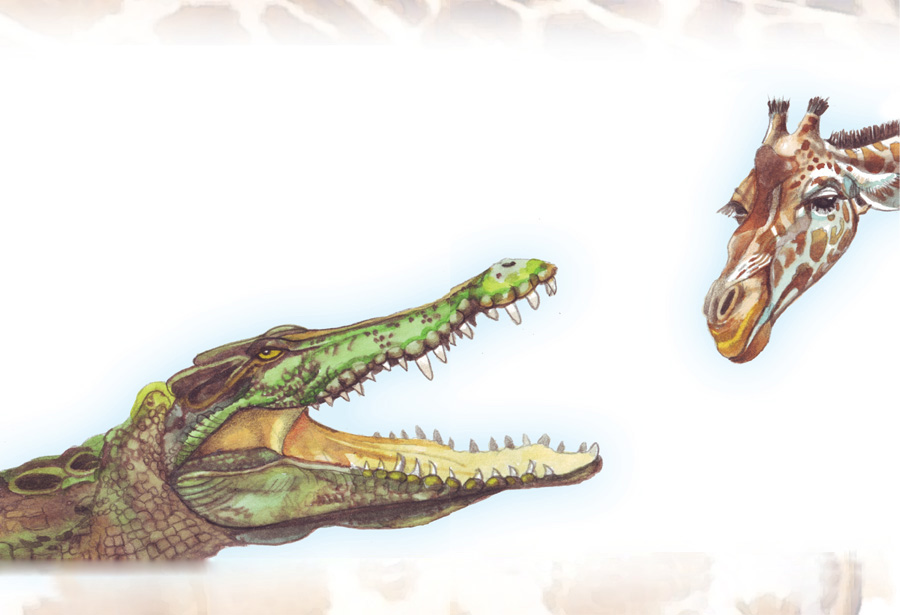

Because she was a village bird, Hen had no idea that the log floating by was not a log at all, but a well-disguised and very hungry crocodile, who couldn’t believe his luck having such a delicious dinner delivered right to his riverbank. And as Hen happily sipped away at her first safari drink of the day, the hungry crocodile swam quietly towards the bank, then sprang from the water, snapping up Hen in one big snap!

‘Oh Brother!’ squawked Hen, her scrawny neck sticking out of a big gap in Crocodile’s brown, rotting teeth. ‘I beg of you, Brother, please don’t!’

Crocodile was so shocked on hearing Hen refer to him as brother that his mouth flew open, leaving Hen to flap out on to the riverbank. ‘Brother?’ he said, not quite believing that he had let his supper go. ‘How on earth can I be Hen’s brother?’

As Hen wandered along the riverbank, covered in chickenbumps from shock, Crocodile had another think. Not only was his belly rumbling and his mouth salivating from the thought of chicken dinner, but one of Hen’s feathers was still stuck between his teeth, making him look extremely silly. ‘I have been tricked by a stupid town bird,’ he grumbled. ‘This time I cannot let her escape!’ So, creeping up behind her, he snapped her up in his jaws. But again, Hen let out a bloodcurdling squawk. ‘Brother, oh Brother,’ she squealed, ‘Release me, don’t eat me!’ Hearing those words, and not wanting to eat a sister, Crocodile let her go.

Crocodile was so shocked by his own actions that he decided to go and seek advice from the Great River God. On his way he saw his equally scaly friend, Lizard, cooling his slippery white tummy on some moss. ‘Where are you off to in such a hurry?’ hissed Lizard.

‘Oh Lizard, I am in a terrible tizz,’ said Crocodile, sliding on to a warm rock. ‘There was a lovely kraal-bred hen who I caught twice, but I just had to let go because every time her lovely feathered flesh touched my tongue, she squawked out ‘Oh Brother!’ Of course, Lizard, I can’t eat my own sister! So now I am off to the water spirit to talk it over.’

‘Don’t bother,’ said the lazy lizard, flicking his tongue languidly to catch a passing dragonfly. ‘Don’t you see, dear Crocodile, that Duck lives near the water and she lays eggs. Turtle lives near the water and she lays eggs. I live in water, and I lay eggs. So do you. We are all brothers of a type. And none of us eats the other.’

‘So we are,’ thought Crocodile, slinking back into the cool depths. ‘I think I will go and catch something else for supper. Something that doesn’t lay eggs.’

From that day on, crocodiles have preferred eating mammals, such as buffaloes or zebras. And hens have rarely gone on safari again.

Told to me in Shona by Isaac Cherenje in Harare, Zimbabwe

Long ago, Hawk and Hen were very good friends. Hen roosted in a kraal with her seven chicks, and Hawk nested on the peak of a high mountain. But although they lived far apart, they still behaved like neighbours, helping each other with favours, food or even feathers whenever the other needed it.

One day, when Hen noticed how straggly her chicks were looking, the first friend she turned to for help was Hawk. ‘Dear Hawk,’ she called to her friend up the mountain, ‘please may I borrow that marvellous razor you found glinting on a hill? My little chicks are looking so ugly and untidy, with their long, unkept feathers. They desperately need a trim.’

Hawk could not refuse Hen, knowing that his neighbour often gave him an egg or two to eat, or a glossy feather for his nest, so he was happy to fly down his precious tool for her to borrow. There was one condition, though. ‘I simply must have it back tomorrow, if you don’t mind, Hen,’ said Hawk, ‘because lots of other birds borrow that razor from me. Of course, I won’t charge you a fee to use it, but I must have it back or there will be a queue of birds complaining.’

Hen was very grateful to Hawk for the loan, and as soon as she got home, she gathered up her bedraggled chicks. One by one she trimmed their dusty farmyard feathers until they looked perfectly round, golden and fluffy again. When she had finished, she marched the sharp razor over to the henhouse, and put it safely on a high shelf where no small feet could step on it.

Once the razor was out of sight, Hen completely forgot about it, continuing her days as normal – scratching for food, nesting in the soft grass, and clucking over her chicks. It was only four days later, when a great Hawk’s shadow fell over the kraalyard, that she suddenly remembered her promise. ‘I do wish you’d get a brain, Hen,’ Hawk chided crossly.

Hen was mortified. ‘Dear friend Hawk,’ she clucked in a great fluster, wings flapping and feathers flying. ‘I put your precious razor in such a high, safe place in the henhouse that I clean forgot about it. Please forgive me. I’ll get it now.’

Hen flew into the henhouse, and with a squawk, flapped up onto the shelf shelf. But where she had put the silver shiny tool, there was a space. The razor had gone. Imagining the look on Hawk’s face when he found out, Hen frantically looked around the kraal. She scratched around on the floor, but it wasn’t there. She peered her beady eye under the children’s nest, but it wasn’t there either. She searched the firestones, in the store, by the water trough, under the maize tray, but it was nowhere to be found. Hawk’s precious tool had simply vanished.

When Hen shamefacedly shuffled out into the kraal to break the bad news, Hawk was furious. ‘Mine was the only razor in the bird kingdom,’ he snapped, his yellow eyes flashing wildly. ‘There is no substitute. It must be returned, Hen. I will give you one more day, then you’ll have to pay!’ With that, he gave a mighty flap, lifted his huge yellow claws off the earth, and with a piercing cry, swept off into the night.

Poor Hen spent all night searching, but found nothing. She demolished her henhouse, searched the straw, picked about in the rubble of the walls, in the ashes of the fire, and even in the rubbish. But she found nothing.

The next day, as promised, Hawk returned as Hen was looking through a heap of long grass. ‘As a neighbour and friend,’ said Hawk, staring at Hen in the eye, ‘I have been very good to you. But I’m afraid this time I must be compensated. In payment, I am going to take a chick for my supper. And tomorrow I will be back.’ Hen was very upset to lose one of her chicks, but Hawk was such a powerful bird, with such big, sharp claws and razor beak, that she couldn’t refuse. ‘I’ll be back,’ he snapped, flying away with a squeaking chick clutched to his breast. ‘I will be back.’

True to his word, the next evening he returned. And despite Hen’s clucking and flapping and scratching and biting, he took another chick. The same has been happening every day until today. That is the reason why, when you see a hen, she is always scratching on the ground. And a hawk is always circling, looking for its payment of a baby chick.

Told to me in Nyemba by Madeleine Chisala in Lusaka, Zambia

Once upon a time, Spider lived with his wife and children in a village. He was a very greedy spider, and ate everything he came across. If he saw a fly passing by he’d pounce and catch it. If he chanced upon a fat worm, he’d slip it slyly into his mouth. And if he got an opportunity to steal a delicious bite of fruit from someone else’s fields, he would. He was the craftiest food-finder about.

The problem was that Spider hated to share. Every day as he ploughed and hoed his fields, he thought of ways to sneak a snack so no one else would see it – or have to share it. He’d chomp a mosquito here and steal a fruit there. Soon he became so good at it that his abdomen became heavy and bloated.

Mrs Spider couldn’t understand it. She was a mere slip of a woman, with similarly tiny children. How could her husband be so fat, she wondered.

One day, her husband came home with an answer. ‘I am sorry to tell you, dear wife,’ he said, holding his bloated body with his hands, ‘but I am about to die.’

While Mrs Spider began to cry, Spider didn’t seem upset at all. In fact, he seemed rather jolly. ‘I have had a message from the heavens,’ he said, smiling, ‘as long as I am buried near our crops in a large coffin with the instruments I need, life will be marvellous. Apparently I will need gardening tools, salt, water, matches and cooking oil where I am going, so I would be grateful if you would prepare them. Oh, and whatever you do, don’t put soil on top of my coffin.’

The next day, the puzzled Mrs Spider set about doing as her husband had ordered. She found a large coffin, some matches, gardening tools, salt, a bottle of water and a container of cooking oil, and, puffing and panting, she dragged them all home. When she got inside, there lay Mr Spider on the floor, dead.

Mrs Spider was very upset. But, knowing how happy her husband was about dying, she picked him up, put him into his large, airy coffin with his food, matches and tools and that afternoon, she and her children buried him in his favourite field. Then they went home sadly to sleep.

With Mr Spider gone, it was up to Mrs Spider to go to the field and pick crops for the family’s dinner. Every day, she took her basket to select fine sorghum, gather fat flies, and pick a perfect pumpkin. But one day she arrived and half of her crops were gone! Her peppers had been pinched, her sorghum stolen, her tomatoes taken and even her pawpaws picked. And because the thief had taken her fruit, there was not a single wiggly worm or fat fly to be found.

As soon as she got back to their village, Mrs Spider reported the theft to the chief. ‘My husband has only been gone a week, and some nasty creature has filched our food,’ wept Mrs Spider. The Chief was suitably supportive and promised that night he would send a group to guard the field. ‘Even if he’s a silent as a ghost, we’ll catch him, Mrs Spider,’ he promised.

That night, as the chief said, a group of fearsome creatures gathered in the maize to watch over Mrs Spider’s fields. Dung Beetle stood guard, showing off his strong front pinchers. Scorpion loaded his tail with painful poison. Snake sharpened his fangs. And Wasp prepared his sting.

By the light of the moon, the creatures stood and watched. At first nothing happened. But soon, as they peered through the maize, they saw the strangest sight they had ever seen – a creature covered in leaves coming out of Mr Spider’s grave. It looked like a walking plant.

‘What’s that?’ said Scorpion, his tail flicking ferociously into the air. But no one knew. As they watched, the creature sat down and made a fire. Then it took some vegetables out of Mr Spider’s grave and started to cook.

‘Ghosts can’t cook, so it can’t be a ghost,’ hissed Snake. ‘Leaves don’t make fires, so it can’t be a leaf,’ whispered Wasp. ‘No nice person keeps his food in a grave, so it must be a naughty thief!’ stuttered Scorpion. ‘Let’s get him!’

The creatures stormed out of the crops, hitting and stinging and flicking the thief. But their punishment didn’t last long. For as soon as the creature began to yell in pain, they recognised his voice. It was Mr Spider!

‘Mr Spider, we thought you were dead!’ squeaked Dung Beetle. ‘We buried you a week ago!’ whispered Wasp. ‘Please tell me you’re not a ghost!’ wept Mrs Spider.

But he wasn’t a ghost. As Mr Spider later admitted to the Chief, he was a terrible trickster. He had pretended to die so he could be buried in his favourite field of food. That way, when no one was watching, he could climb out and eat as much as he liked. Without asking anyone. And without sharing.

The creatures all agreed that no one had ever been such a mean husband. Or such a rotten liar. As punishment, the chief ordered Mr Spider to spend his life in a corner, with his back to the world. No one would ever talk to him again.

That’s why, still today, most daddy long-legs spiders spend their lives by themselves in corners. It is punishment for their greed and for pretending to be dead.

Told to me in Ndebele by Benicah Ncube in Bulawayo, Zimbabwe

Once upon a time there was a fruit that grew only at the very top of a tall mountain in the south of Africa. The fruit hung, ripe and rich and red, from the branch of a tall tree, and from the forest in the valley below, all the animals could see it. But none of them had ever tasted the fruit, because the mountain was too steep for them to climb.

The animals all looked up longingly at the red fruit, imagining its sweet, succulent taste. And the more they looked at it, the more they wanted it.

One day they could stand the temptation no longer, so the king called a meeting to decide how to get a taste of the forbidden fruit. Hare was the first to speak up. ‘Being a great jumper, I could reach the fruit easily,’ he said (in that smug way that hares do). ‘But I might not be able to resist taking the first bite of it. I think we need someone trustworthy. Why don’t we ask Tortoise first?’

The animals all thought this was a very good idea. ‘He’s slow, but he’s steady and honest,’ they agreed. So the next day Tortoise was dispatched, up the path, over the river, and step by precarious step, up the slippery slopes of the mountain. He climbed, and struggled and slid. But halfway up, the cliff was too much for his flat, scaly feet to hold on to and he flipped onto his back, and slid all the way back down into the forest on his hard shell.

The slope, it was agreed, was obviously too great for such a small creature to try. So, after helping Tortoise back onto his feet, they asked Kudu to try next. ‘Please Mr Kudu,’ they begged, ‘make the leap into the land of the fruit tree, and bring a taste of the forbidden fruit.’ With a toss of his curly horns, Kudu trotted off, and was soon high on the slopes. But he too failed, for no sooner had his hard hooves touched the slippery rocks than he began to stumble and eventually tumble - a mass of flying hooves and hair, off the mountain slope and into the jungle.

Baboon tried the next day – and fell when the cliff face began to crumble. So Hare came to the conclusion he should indeed try himself. He said to the other animals: ‘I am sure of foot and nimble of paw, I am as sharp of brain as I am of claw.’ And that, the confident creature felt, was reason enough to be the one to pursue the pleasures of the forbidden fruit.

Hare was right in one way. Unlike the other animals, his route didn’t go up the path, over the river and up the slope. That was far too difficult, he decided. Instead, it went around the less steep slopes of the mountain, and up to the top. It was simple, and by sunset, the big-headed animal was back in the forest, triumphantly calling the others to see the rich, red, ripe fruit he held in his paw.

There was great excitement as they gathered, with everyone jostling and pushing and shoving to get near it. The fruit not only looked irresistible, but its fragrance was the sweetest anyone had ever smelt – mango and honey and strawberry all rolled into one.

They all wanted to try it, and soon a riot had begun. ‘I’m the biggest, so I should be the first to tickle my tastebuds,’ trumpeted Elephant, heaving forward. ‘Stuff and Nonsense! Make way for the monarch!’ roared Lion, flicking his tail. ‘Hold on, hold on – what about me!’ snorted the Hippo, flaring her nostrils.

It was all going precisely as Hare had planned. While the animals rattled and roared, and harrumphed and hawwed, the clever little creature put the forbidden fruit under his arm and slipped off into his burrow for a private feast.

The rest of the animals have still never tasted the forbidden fruit. If you see them now near a mountain, watch and see. They will still be looking up trying to spot another tree.

Told to me in Chichewa by Evalena Njovu at the Latete leper colony in Zambia

A long time ago there lived two brothers, Mabvuko and Masoka. Mabvuko was a rich man with a beautiful house, and many servants. But greed had made him mean and arrogant, and no one liked him. Masoka, however, was the most generous, kind man in the land, always sharing whatever he had. If he caught three fish, he would give away two. If he found a mango tree bulging with fruit, he would call the other villagers to feast. If he came upon a sweet stream in the mountains, he would fill his pot so he could share it on the way home.

One night, Masoka dreamt that while he was sleeping on his mat under a tree, a beautiful girl called out to him. ‘Come to the river,’ she sang sweetly, ‘Come and see what the Gods have given to thee.’ Once he reached the river, the beautiful girl clapped three times and from the depths of the murky water rose the finest canoe he had ever seen. Three more claps produced paddles. Then the beautiful girl said to him, ‘Now, Masoka, go and gather me some fish. When you bring them back, though, be sure to cut the heads off.’ He did as he was commanded, and when he got back with the headless fish, the beautiful girl cooked them for him, then kissed him on his forehead.

When he woke up the next morning, Masoka was very disappointed to find it was all a dream. ‘Never mind,’ he sighed, picking up his fishing rod and heading for the river. ‘I do not have my Dream Girl, but perhaps I will catch a fish.’

When he arrived at the river, Masoka was amazed to find not only the beautiful canoe he had dreamt of, but a pair of fine wooden paddles. Joyfully, he leapt inside and paddled out to the middle of the lake, where he caught the biggest fish of his life. Mindful of his dream, though, he cut off its head, before heading back home to cook it for lunch.

Imagine Masoka’s amazement when he found in place of his old mat a fine thatched house, with carved wooden furniture, nine servants who bowed down before him, and, on the verandah, his Dream Girl who came out to greet him. She had been sent by God, she explained, to reward Masoka for his kindness and generosity, and to console and comfort him. Never again would he be lonely, hungry or thirsty. The only thing he had to promise, she reminded him, was never to bring home fish with their heads still attached.

Masoka had never been so happy. Every day he laughed with his Dream Girl, fished in his canoe, had his dinner cooked by servants, and went to bed in his beautiful house. His rich brother, Mabvuko, even came to visit to witness his brother’s sudden wealth.

Soon, though, Masoka began to tire of cutting off the fish heads. Why did his servants have to clean and behead them at the river, he moaned, when they could do it more easily at home? His promise to his Dream Girl was a ridiculous one. She’d soon get used to fish heads. And the sooner he took them home, the sooner she’d get used to them. That very afternoon he ordered his servant to take his catch home whole. The boy paled and started shaking when his master made his command. ‘But sir,’ the boy protested, his eyes wide with terror. ‘You know your wife’s wish. I would rather run away than risk her wrath.’

‘Fine!’ shouted Masoka. ‘Then run!’

That night, Masoka went home without one servant – and the fish heads still on. With the next day’s catch, he commanded his second servant to do the same. That servant, too, refused, and the next, and the next, until on the ninth day, Masoka had only one servant left. ‘I command you,’ he shouted to the boy at the river, ‘take the fish home!’

This time, though, the boy took such fright that he ran all the way home – with the whole fishes – to warn his beloved mistress. By the time Masoka had arrived back, not only had his servant vanished, but everything he loved: his beautiful home, his carved ebony furniture, his cupboard full of food – and his beloved dream girl. All that was left was his old mat under a tree.

Masoka fell on his knees, and wept, and prayed to God, promising that he would never ever bring home fish heads again. But it was too late: he had broken his promise.

And as Masoka had learnt, once one breaks a promise, something precious is lost forever.

Told to me in Ndebele by Justice Chinamhora in Harare, Zimbabwe

There was once a father who had only one son. He was very proud of his son, and had brought him up to be honest, brave and kind. One day the father became very ill. As he lay on his deathbed, he called out. ‘My beloved son,’ he said. ‘I want you to make me three promises before I die. If you keep them, you will be happy for ever.’

His son nodded respectfully, promising his father he would do whatever he asked. ‘First you must promise never to talk about other people’s business,’ the father said. ‘Then you must never reveal to your wife the secrets of your heart. And finally, when I am dead, you must cut off my index finger and bury it near your hut. But you must never tell anybody.’ Then the father closed his eyes, and died.

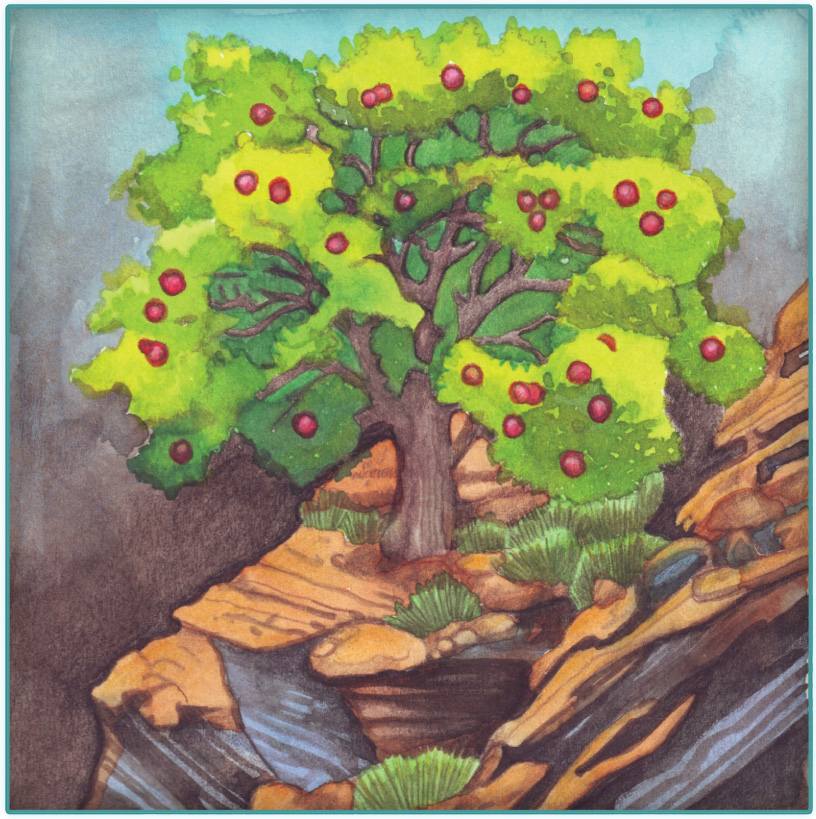

The son was an obedient boy, and before his father was buried, he cut off his index finger, and put it in a hole near his hut. At first nothing happened above the hole. But soon, after the great rains, a beautiful tree grew. It was the most magnificent specimen anybody had ever seen. Its trunk was the size of an elephant’s body. Its branches were big enough to seat ten leopards. Its sap was so sugary it made sunbirds sing. And its flowers were so sweetly scented that girls would beg their lovers for a gift of just one red bloom.

Villagers came from all over the land to see the marvellous tree. Everyone wanted to know where he had got it, but the boy, remembering his promise, never revealed the secret.

As the tree became more famous, visitor after visitor arrived, many with gifts for the boy. People offered him cows in return for the secret, and cloth, and gold, but still the boy kept his pledge.

In the next village lived a cunning man who was jealous of the son’s fortune. He wanted the tree more than anything in the world, so he too could be brought gifts of cloth and cows and gold. He tried growing a seed, but it shrivelled. He tried planting a stolen branch, but it died. There must be another way, he thought, trying desperately to think of a plot.

One day the greedy man had an idea. He told his most beautiful daughter to pack her bags and go to the boy’s village with permission to be his wife. When she was there, he said, she should use her wiliest charms to win the secret of the tree. She was not to return until she knew it.

When the girl arrived at the village, the boy was so bewitched by her beauty that he happily agreed to marry her. As soon as the wedding was over, the girl did as her father had instructed, and set about winning her husband’s heart. She cooked his favourite meal of goat stew and maize, and made him the finest beer. She kneaded his sore feet after a long day’s work and carried cool river water to the fields for him to drink. But no matter how strong her feminine wiles, she never managed to obtain the secret.

A year after the marriage, the couple had a baby son. The husband was delighted and went to great trouble to show his wife his affection. He procured special treats for her to eat and arranged a great celebratory feast. He found the best nursemaid in the land to help her and wrapped the baby in the finest cloth. And he showered his wife with love and attention. He had never, ever been so happy.

After the great feast, the wife thought she would try again to learn the secret. ‘My brave warrior,’ she said to her husband, fluttering her big brown eyes at him. ‘I know you love me dearly, and want to make me happy. But if you want me to be the happiest woman in the world, tell me just one thing.’

‘What is that?’ said her happy husband. ‘What is the name of our beautiful tree, and how did it grow?’ she asked again.

The husband loved his wife so much that he felt he couldn’t hide the secret from her any longer. ‘Your heart is my heart,’ he said, ‘so I will tell you. But you must promise to tell no one else – not even your mother and father.’ His wife promised, and so he told her. ‘The name of the tree is Finger of My Father,’ he said, ‘and it grew out of the trust of our hearts.’

That night, while her husband was sleeping, the wife packed her belongings into a bundle, picked up her sleeping baby and crept out of the village to journey to the house of her father.

The father was delighted with her discovery, and by morning he had spread the news around the entire village. ‘Finger of My Father, the tree is called,’ he trumpeted self-importantly. ‘Finger of My Father.’

While the girl’s father was celebrating his discovery, her husband was waking up to find his wife and his baby gone. ‘My beautiful wife,’ he cried, ‘and my precious son! Why, Gods, are you punishing me?’ When he heard the villagers outside shouting ‘Finger of My Father’, he knew at once. He had broken the most important pledge a man can make – that to his father and mother – and was now being punished. He knew that he had not only lost his family, but that he had to leave his village. His ancestors’ spirits would ensure that, if he stayed in his father’s village, he would have bad luck for ever.

Sadly, he packed a small bundle of clothes and food, took his hunting stick and spear, and walked out into the valley to live a life alone. The Finger of My Father tree never flowered again. It still grows, green and tall, its flowerless branches acting as a reminder of the power of broken promises.

Old African proverb:

‘He who marries only a beauty marries trouble.’

Told to me in Xhosa by Mabutinki Mafatshe near Rustenberg, South Africa

Long, long ago, when the earth was still young, Lion was the only animal that had a tail. ‘But then I am the king,’ he reasoned, flicking flies off his body with his long, muscly tail, ‘so if anyone should have a tail, it’s the royal me.’

As the summer wore on, Lion began to notice how infuriated the flies made all the other animals. Swarms of the little black insects buzzed and they bit, and they flew and they nipped, but none of the animals had anything to whisk the flies away.

Lion eventually began to feel sorry for them. ‘As the king, I think it’s time I helped my subjects by giving them tails,’ he decided. ‘I won’t give anyone a tail as long as mine, of course, because only the king should have such a magnificent specimen. But I will give each of them something that will help them to flick away those pesky flies.’

That morning he started to make all sorts of tails – long and short, thin and fat, spiky and bushy, and round and stubby, spotted and striped. By midday, he’d fashioned all sorts of attachments, and hung them in a row on a long branch so he could admire them.

After he had decided which tail to give to which animal, he summoned one of his trusty messengers, Baboon. ‘I have decided to give all the animals a gift,’ he said to the rosy-bottomed creature. ‘Please go and tell them I wish to see them tomorrow morning. Every single animal must come, as I have a gift for each of them.’

The baboon, delighted at being given such an important task, was soon jumping from rock to rock and tree to tree, running through grass and over rivers, relaying the royal message. He told Elephant and Hippo, Kudu, Eland and Impala, Antbear and Monkey – every animal from the largest to the smallest. ‘And every animal must come,’ said the baboon, ‘because our king has made each one of us a special present.’

The animals were all very excited, for it wasn’t often the king gave away gifts. Only the fat, furry dassies, were not bothered – they are lazy animals who would rather lie in the sun on a rock than walk into the valley to see the king. So they thanked Baboon, then dozed off again on their warm rocks.

The next morning, the valley streamed with excited creatures, on their way to get their gifts. Only the dassies lay about on their rocks. ‘Aren’t you coming, dassies?’ shouted the troops of monkeys, as they chattered past. ‘The king will be very cross if you don’t!’

The father dassie rolled over on his tummy and looked at them through half-closed eyes. ‘No,’ he said lazily, enjoying the warm rock on his belly. ‘I’m sure he won’t have anything for such small and insignificant creatures as us. If he does, though, would you mind bringing it back for us?’

The monkeys reluctantly agreed, and went on their way, swinging and screeching through the trees into the valley. When they got to Lion’s royal rock, there was their king, proudly surveying a branch on which he’d hung of all sorts of tails. There were dotted ones and striped ones, long ones and short ones, stubby ones and fluffy ones, straight ones and whirly ones. They were all sorts of colours, too – red and striped, or yellow and dotted, or black and white. What a fantastic array!

The animals roared and chattered and screeched with excitement, each trying to guess which tail they’d get. ‘Silence!’ roared the king, getting flustered, ‘or you will make me forget which one I made for each of you.’ The king, you see, was getting a bit old and his memory was fading. He picked up the first tail on the branch – a tiny one with sharp black bristles – and then called out. ‘Right, Antbear, I think I made this for you. Oh, actually, no that’s a mistake. I think it’s for Monkey. No, I mean, um, oh dear, I can’t remember! Oh yes! It was for Hippo! Come Hippo, come and collect your tail!’

While Hippo was very pleased that he’d been the first animal to be given his tail, he was not very pleased about its size. What was a great big animal like him going to do with such a tiny tail? It wouldn’t do at all do have such a stubby specimen! But he couldn’t complain, so graciously he let the king attach it to his bottom and then showed it off to the other animals.

The next tail on the branch was a great brown bushy creation that fluffed out at the sides and waved about in the air. It was so beautiful that all the animals wanted it. But once again the king paused. ‘Now who did I make this for?’ he said, scratching his head absentmindedly. ‘Was it for Giraffe? Or for Rhino? Oh gosh, I can’t remember. Well, it is brown, so I guess it must be for a brown animal. I know! Squirrel! Come forward Squirrel!’ And so the surprised squirrel bounded forward for his magnificent tail, which he then flicked backwards and forwards with pleasure, showing it off to all the other envious creatures.

The tail-giving went on all afternoon, until at the end of the day, every single animal had a tail. But still there was one left hanging in the tree. ‘Now this one I remember specifically making,’ said the king. ‘I made it for Dassie. Step forward Dassie!’

No one stepped forward, and animals were silent. ‘Dassie, step forward please!’ roared the Lion again. But still no one moved. Then Monkey edged forward slowly. ‘Excuse me King,’ he said, holding his new long black tail over his arm. ‘But Dassie was busy sunbathing this morning. So he asked me if I would collect his tail for him.’

The king was furious. He had spent a long time making the tail for Dassie, but the rotten little rock rabbit hadn’t even bothered to come. Still, it would be silly to let that tail go to waste, so he handed it to Monkey and sent everyone home. Soon the valley was full of happy, chattering animals, waving and admiring their handsome new bottoms as they wandered off into the sunlight.

As he had promised the king, Monkey carried Dassie’s tail carefully over his arm. But as he got nearer Dassie’s rock, he began to look at it enviously. ‘Why should lazy Dassie get a tail at all if he couldn’t be bothered to collect it himself?’ he said to himself. ‘It is such a fine long tail and if I added it to mine, I would have the longest in the kingdom. Even longer than Lion’s!’

So the naughty monkey took the end of Dassie’s tail and stuck it on to the end of his own. The combination of his own long black tail and Dassie’s little white fluffy blob on the end made Monkey’s tail the finest the kingdom had ever seen.

Dassie of course never got a tail at all – something he’s enormously embarrassed about. Even today, if you spot him, he will lower his bottom and hide with shame behind a rock.

But its laziness is still remembered today. You will still hear the Xhosa people say: ‘I-mbila yaswel’ umsila ngoku-yaleza’ which means ‘If you act like a dassie, you will get the rewards of a dassie’. Which, as poor Dassie learnt, means no reward at all.

According to the Shona storytellers of Zimbabwe, the week after Lion gave out tails he gave out nipples too. All the animals gathered round the baobab tree to be given tips for their breasts. But Hen couldn’t be bothered to go; she was too busy scratching for corn. So her friend Dog agreed to collect them for her. On her way home, Dog had a crafty plan. ‘If I had extra nipples, I could feed all my puppies at once,’ she thought. So, instead of delivering Hen’s nipples to the chicken kraal, she attached them to her own body – one line of nipples along the left side, and one line on the right. She was very pleased, for ever since she has been able to feed six puppies all at once. Hen, though, has no nipples. The next time you see a chicken’s breast, have a look. Can you see any?

Told to me in Bemba by Godfrey Chanda, a subsistence farmer, near the Kalamazi rose farm, outside Lusaka, Zambia

When Man came to live on the earth, God put him in a beautiful valley. The valley had clear rivers to drink from, tall trees to rest under, strong grass to thatch his huts and bountiful rain for his crops. Man loved his home.

In those days, Man had never seen an animal and the animals had never seen a man. God had separated them – animals on one side of the lagoon, and Man on the other. Man could hear the lions roaring, the hippos Hmmmmmhmmmmhmmming, the hyenas cackling and the baboons howling on one side of the lake. And the animals could hear Man singing and drumming from his side. But neither had ever met.

One day the animals’ curiosity got the better of them, so they held a meeting to decide how they should go about meeting their neighbours. ‘Firstly, we need to see who they are,’ said King Lion at the meeting. ‘Then, secondly, we need to find out what that delicious smell is that wafts across the valley. If we knew what it was, perhaps we could have it too.’

The animals agreed. But no one could agree whom to send to meet Man. The small animals were too scared to go. The buck couldn’t swim to the other side. Rhino was too bad-tempered to meet anyone. Giraffe was too tall to swim all that way. And Lion was too fierce. So Monkey volunteered.

‘Don’t be silly, Monkey,’ said Elephant. ‘You are far too naughty.’ But then the king spoke. ‘Yes,’ he said, ‘Monkey is naughty and can be very noisy. But who else has the skills that Monkey has? He can run on land. He can swing in trees. He can swim in water. He’s got the brains to escape if he needed to. I think that’s a very good idea – Monkey, you are the one.’

Monkey was very excited at being chosen by the king, and after he had waved all the animals goodbye, he started the long swim across the lagoon to the area where Man lived. He swam and he swam and he swam, his long tail trailing behind him. When he eventually pulled himself up on to Man’s land, he couldn’t believe his eyes. Instead of a jungle, there, in front of him, were huge areas of flat land, planted in rows with plants. Instead of trees to live in, there were little round shelters covered with thatch. And instead of an assortment of furry creatures walking around – like where he came from in the jungle – there were strange, upright, furless creatures who carried shiny tools about.

Monkey didn’t like the look of them at all. So, instead of introducing himself to Man, he quietly climbed a tree where he sat all day and watched what Man did. He saw him hoeing and ploughing, making fires and cooking, and washing and sweeping. Then, in the afternoon, he watched Man going into the rows and rows of plants and picking off them long green vegetables that smelt sweet and ripe. ‘That was the smell that had wafted across the water!’ Monkey thought excitedly. ‘I will have to take one back for the king.’

That evening, when the men gathered in a circle round a fire, Monkey climbed from his tree and crept quietly into the field where he’d seen the men picking. The smell was like nothing he had ever smelt before – a mixture of butterfruit, and marulas and guavas and cabbage all rolled into one. Looking round to make sure no one was watching, Monkey pinched one. Hiding in the stalks, he peeled off its green layers and slowly started to nibble. The thing was delicious! So he had another. And another. And another, until his stomach was as round as a melon. ‘I think it’s time to go home now,’ he thought, satisfied at his feast. He packed two into his little bag, and happily sauntered back to the lake to swim home.

Imagine his horror when from behind a bush jumped a man with a net which he placed over Monkey’s neck. ‘Screeeeeeeech! Screeeeeeech!’ screamed Monkey in terror. ‘Please let me go. I was sent by the king and I must return. Do not harm me, please!’

The man was not convinced, though. ‘Sorry, but in our culture if someone steals from us, we take his heart away,’ the man said. ‘And while I have never seen a creature like you, you have stolen from us, and I must take your heart. Please give it to me.’

Monkey had never heard of this custom, but, as King Lion had said, he was a fast thinker in times of trouble. ‘Oh Clever Man, Oh Kind Man, Oh Generous Man,’ he said craftily. ‘I am from the animal kingdom and we do not keep our hearts in our bodies. Our king keeps them for us. I agree that I have done wrong to you, and that I should give you my heart. So please will you row me across the river to my king.’

The man did not know what to do. He had never heard of a king keeping hearts before. But then again, he had never met a creature with fur on. So he agreed and soon he and Monkey were in his boat, rowing across the water towards the jungle.

Once they got near the jungle shore, Monkey started singing a song. The man couldn’t speak his language, so he couldn’t understand it when Monkey sang: ‘Crocodiles, crocodiles, come out and greet me, or else this man is going to eat me!’ One crocodile appeared. Again Monkey sang it. Another crocodile appeared. Monkey sang and sang and sang until the boat was completely surrounded by hungry crocodiles, forming a bridge between him and the land.

Monkey then jumped out of the boat and jumped across his friends’ backs into the jungle. ‘Foolish man!’ he shouted. ‘Do you not know that animals’ hearts are in the same place as yours, and feel pain as strongly as you do? Know now that if you try to take our hearts, you will have to face all the animals in the jungle. We are all friends and you are our new enemy!’

And as he said it, the crocodiles all rose up out of the water and tossed the man into the air, and into their waiting mouths.

Man still hates monkeys for stealing his maize. And monkeys still remember their first meeting with Man. Today, if you see a monkey, watch what he does to his chest. He beats it with his fist in the very place his heart lives. It’s a reminder to Man that animals have a heart, just like he does.

Told to me in San by Kgao Xishee in XaiXai, Botswana

Once upon a time, when the earth was still very young, Man had never seen fire. Everything he ate was raw – roots from the soil, milk from cows, eggs from birds, and fruits from the trees. All the heat he needed came from the sun – from its bright rays during the day, and the warm sand at night. And all the water he drank came from cool streams. Man wanted for nothing.

One day, when he was out hunting, Man looked up to the horizon and saw a tall, thin cloud spiralling up into the sky from the side of a mountain. He had never seen a cloud climbing from the ground before so, carrying his spear, he went to investigate.

Man got closer and closer, until at last he reached the mountain. There, on a stony ledge, he saw the cloud on the ground, cloaked in orange and red, and shooting out sparks and red trails. Man had never met a cloud like this, but, being a friendly man, he approached it with a smile. ‘Hello stranger!’ he said. ‘I have lived here since the earth began, but we have never met before. Who are you?’

The fire was very pleased to have visitors, and urged the man to come closer. ‘Please,’ he said, ‘warm your body on mine and enjoy my light. I am Fire, servant of the great creator of the sky, and am here to add pleasure to the world. Come closer, come closer.’

Man did as he was invited and was astonished that the nearer he got to his new friend, the warmer his body became. And the longer he stayed, the happier he felt. At the end of the visit, he was quite reluctant to leave. ‘Please Fire, come and visit my home,’ he begged. ‘I would love my wife and family to feel the warmth of your company and the light of your face. Perhaps, if you liked them, you might even stay for ever.’

Fire had enjoyed Man’s company immensely, but sadly said no. ‘It is very kind of you, Man, but everything has its home, and mine is here,’ he said. ‘But please come and visit whenever you like.’

On that condition, Man left, and as soon as he was home he told his family about his new friend. ‘You’ve never met anyone so beautiful,’ he exclaimed. ‘His feet were blue and purple, his legs and body swathed in red, and around his head darted flickering lights of yellow and gold. Even his breath, wife, was a sight: all clouds of blue and grey, with a crackling laugh. Oh, how I enjoyed meeting him!’

Again and again Man went to visit, every time begging his friend to return home with him. Eventually, his friend gave in. ‘But please don’t blame me if things go wrong,’ Fire said to Man. ‘I have an uncontrollable appetite and sometimes can’t help eating everything in sight.’

Man happily agreed, and then set off home where he asked his wife to prepare the most sumptuous feast the village had ever seen. She cut fine fruits and dug up their favourite roots. She milked cows and sliced vegetables. And, as a special treat, Man gathered two ostrich eggs to drink. Fire had said he had an appetite, he thought proudly. But there was no way he would be able to eat all of this!

The day of the visit eventually came and on the horizon Man could see Fire leaving his mountain, his spire of smoke rising gently into the sky. At first, Fire was well-mannered and quiet. But as he got hungrier on his way down the mountain, his fingers began to flicker out greedily, snatching little mouthfuls of grass, then patches of dry bush. Soon he was eating everything in sight, his enormous flames pulling down trees and crisping the countryside. The friendly fire had turned into a big bad blaze.

Man wasn’t sure what to do. At first, he enjoyed the sight of his friend’s colourful body marching through the bush. Then, as birds and bushbuck started to flee past him, he began to worry. His friend had eaten huts, then trees, then the crops. What would happen when Fire got to him? He soon found out.

In a cloud of smoke and sparks, Fire arrived at Man’s house and demanded food. ‘I’m here, Man,’ he roared, red arms flaming up into the sky. ‘I’m hungry and I want to eat.’ And from his body shot a great flash of light.

Man had never felt such heat, and with a scream, he and his wife ran from the fire until they got to the river. They jumped into the cool water and there they stayed, until at last Fire burnt himself out, and his great red body vanished in puffs of clouds. At last they were safe.

Sadly, Man and his wife wandered home. They had lost everything – their house, their fields and their crops. All that was left was a big black mess – and the black, burnt remains of the feast. But something else had happened in the house: the smell had changed. As they wandered from plate to plate, great wafts of perfumes they had never smelled before rose from the burning embers: crisp hot potatoes, boiled milk, roasted carrots and baked eggs.

They looked at each other in puzzlement. This wasn’t what their food normally smelled like. So they picked it up, and nibbled. It was delicious. And it was warm and soft. ‘You see, Wife!’ said Man excitedly. ‘Our friend may have ruined our house, but look what he has done to our food. It’s a feast fit for a king!’

They called their neighbours, and from all around villagers flocked to taste the feast Fire had created. It was the tastiest food they had ever had. Soon, everybody wanted to invite Man’s friend Fire into their kitchen – if he behaved.

With so many new friends begging him to return, Fire at last agreed. But this time he insisted that Man came to fetch him. As everyone had learnt, when Fire is left on his own, he has an unstoppable appetite. But if he is collected, and is surrounded by special stones that stop him wandering, he can be their best friend. He is warm. He brings light. And he improves good food. What more could a man need from a friend?

Told to me in Chichewa by Robert Temba outside Lusaka, Zambia

A long time ago, Hare, Lion and Hyena were friends. They ate together, they drank together and they hunted together. Every sunset they would sit by the waterhole, drinking and talking about the meaning of life.

One day, Hyena came to the waterhole with a puzzled face. ‘Hare,’ he said to his friend. ‘I keeping hearing animals talking about lucky and unlucky, but I don’t know what the words mean. Would you please tell me?’

Hare wasn’t quite sure how to explain the words to Hyena. ‘Just remember that lucky animals talk and unlucky ones don’t,’ he said. Hyena scratched his head. ‘I still don’t understand,’ he said, looking downcast. ‘Well, if you wait,’ said Hare, sighing impatiently, ‘maybe one day I will show you.’

Later that week, Hare met his other friend Lion for a drink. He noticed his friend was looking weak and thin. ‘Are you all right, Lion?’ asked Hare, concerned about his friend. ‘Not really, Hare,’ said the skinny lion. ‘I am starving and haven’t eaten for weeks. Look, you can even see my ribs.’

It was true. The lion’s body was as thin as a snake’s. Hare thought for a while, then came up with a plan. ‘Meet me down at the riverbank at sunset,’ Hare said, ‘and together we will try and find supper.’ Lion thanked him and, dreaming of food, he padded home.

Hare then went to visit Hyena. ‘Your lucky day has arrived,’ Hare said. ‘Come with me and I’ll show you what lucky really means.’ Then he led Hyena down to a large tree on the riverbank and told him to climb it. ‘But once you are up, don’t move or make a sound,’ he warned. ‘Then you will understand what lucky means.’ Hyena did as he was told, and soon all that was visible of him was his reflection in the river below.

Hare then settled down and waited for his friend Lion to arrive. Soon he saw the thin creature wandering up the riverbank. ‘My friend Lion, I’m so glad you’ve come,’ said Hare, bounding up to him. ‘Look what I have seen for your supper.’ He pointed to the river, and, sure enough, on the shiny flat surface of the water Lion could see a delicious fat-looking Hyena.

Lion couldn’t believe his luck – supper, and so close, too! He sharpened his claws, focused his eyes, crouched down and, with a great roar, sprang onto the hyena on the river. But what a shock he got! Instead of delicious supper in his mouth, he got a throat full of water. ‘Oh Hare,’ Lion choked, coughing and spluttering as crawled out of the river, shaking water off his coat. ‘I’m not sure what happened. One minute there was a hyena in front of me, and the next minute I was drowning, and now I am wet and cold, as well as hungry, so I think I should go home.’ And off Lion padded, dripping down the path.

Hyena lay on the branch shaking with fear. He couldn’t believe that his old friend Lion would ever try to eat him. ‘Well, Hyena, you certainly know what lucky means now,’ laughed Hare as the quivering creature climbed down the tree. ‘You can still talk, can’t you? That’s a sure sign you are lucky.’ Hyena nodded and, thinking about the lesson he learnt, he wandered home.

A few days later, though, Hyena had another query. ‘Hare, I now know about lucky,’ he said. ‘But what about unlucky?’ Hare was fed up with all this questioning. ‘I have told you before: those that can talk are lucky and those who can’t are unlucky. That’s all,’ he said crossly.

‘Just be grateful you can talk.’ But Hyena pestered him so much that eventually Hare gave in. ‘Right, you want to see what unlucky is?’ he said in a grumpy voice. ‘Fine. Climb that same tree at sunset and I’ll show you.’

When Lion and Hare met that evening for their daily drink, to Lion’s amazement, he saw yet another fat hyena lying on the river surface. After his last experience, he was very reluctant to try catching the creature again, but he was still very hungry. So he took Hare’s advice. ‘The thing with life is that sometimes you are lucky and sometimes you are unlucky. Sometimes you have just got to look for the right signs,’ he said.

Hare then stuck his second finger up into the air and pointed at the tree. Lion wasn’t quite sure what Hare meant, but, as he’d been told to follow signs, he followed the finger and looked up. There, on a branch overlooking the river, he spotted Hyena. ‘Dinner!’ he roared, and leapt up the tree. Soon, after a bit of biting and fighting, he was munching and crunching, having the best supper he’d had in a long time.

The crafty Hare left Lion to his feast, and went home whistling down the path. ‘I suppose it’s a pity that Hyena learnt his lesson such a hard way,’ he said to himself. ‘But he didn’t listen. I told him lucky creatures could talk and unlucky ones couldn’t – so you would have thought he’d have understood the warning.’

Hyenas have been much wiser ever since. They are not friends with any one today – particularly crafty hares and hungry lions. Whenever you see them, watch the way they look at lions with suspicious eyes. They remember that day in hyena history when their ancestors learnt the meaning of unlucky – the hard way.

Told to me in Shona by Miriam Mlambo, who has been telling traditional stories on Zimbabwean radio since 1956

Hyena has always been a lazy creature, living off the scraps from other animals’ meals, but a long time ago, he didn’t even want to do that. He wanted someone to look after him, to provide for him and feed him. ‘What I need is a wife,’ he thought, as he lay lazily under a tree, panting in the heat. ‘She cannot be a hyena, for like me she will prefer lying in the shade. I need another kind of wife.’

One day, as he was walking through the forest to the river to get some water, he saw the most gorgeous bird he had ever seen. She was standing in a shallow pool, fishing, and as she dipped her head delicately into the water, Hyena noticed her soft grey wings, her delicate white feathers and her long golden legs.

‘What a beauty!’ Hyena thought excitedly, as he brushed off his dusty spotted coat and padded towards the pool. When he got there, he slunk forward and, with a sly smile, introduced himself to the bird. ‘Good morning, beautiful stranger,’ he said, his tail slinking to the ground. ‘I am Hyena, King of the Jungle. Who, beautiful bird, are you?’

The heron was flattered that she, a simple bird, should be visited by a great king and her head feathers flushed with excitement. ‘Why, I live here by the water, in a big nest with my family,’ she said in a friendly voice. ‘None of us has ever met a hyena before and I am sure my family would be delighted. Can I tempt you to visit?’

Hyena was delighted, for he knew that an invitation like that usually meant food. Being a greedy fellow, who enjoyed a good gorge, he accepted at once, and soon he and Heron were walking happily along the riverbank towards the heron family’s great nest. As Hyena expected, the family laid on a great spread of fish and frogs and crabs and small birds – all freshly caught that morning. He had never had such a fine fresh feast.

Having thanked the family, that evening Hyena set off home and again began to think about a wife. ‘Wouldn’t it be a fine thing,’ he thought, ‘to be served such a fine feast every day? Perhaps I should marry the heron!’ The more he thought about it, the more he liked the idea of being served. So the next day, after a quick wash in a jungle pool, he set off early to ask Heron’s father for his daughter’s hand in marriage.

Mr Heron was delighted. No heron had ever married an animal before – never mind a king – and he and Mrs Heron soon set about preparing a great feast for the wedding of their daughter.

The great day came and Hyena settled happily into the great heron family and being waited on by his dutiful wife. But one day she came to him. ‘Husband, oh King, oh Lord of the Jungle,’ she said dutifully, lowering her head before the lazy beast. ‘The other male herons are going out fishing this afternoon and have asked you to go with them. Can I prepare a fishing sack for you?’

Hyena had never been fishing before, but not wanting to be outshone by the others, he grumpily agreed. When they got to the river, though, Hyena remembered why he had never been fishing before: he hated water and he couldn’t swim. He had to find a way out of it. ‘Brother Herons,’ he said craftily. ‘I know a pool where fish are plentiful, but can only be reached by those with legs. So I will have to leave you here. But I will see you later with my catch.’ And off he slunk into the undergrowth.

Hyena headed toward a small, shallow pool along the river he’d seen. But once he got there, he stopped. How did one catch fish? he wondered. Besides, what did a live fish look like? He has never seen a live one in his life. Slowly, he walked to the edge of the pool, and careful not to fall in, he looked into the water.

There, in the cloudy green pond were all manner of moving creatures, leaping and hopping about. Some were fat, some thin, some high-jumpers, some long-jumpers. All were green. ‘Marvellous,’ thought Hyena, howling with laughter. ‘This will take me no time!’ He took his bag, scooped it into the water and soon had a sack full of wriggling creatures to take home.

Back at the clear pond, the Herons were having less luck. ‘Well, that’s why I am a king and you are not,’ said Hyena with a smirk. ‘See you later.’ And off he slunk back to his wife’s tree, under which he settled for a snooze.

At sunset, when the herons strutted back with their bags of fish, there was great excitement. Each bird lined up with his bag, and one by one, emptied the wriggling silver piles of fish onto the grass. Then came Hyena’s turn. ‘Of course, it took me only a few minutes,’ he said arrogantly, and turned his bag upside down. When the contents fell out, the herons couldn’t believe their eyes. On the ground lay a greasy, messy, wriggly, heaving mass of smelly green frogs.

The herons burst into howls of laughter. ‘Kraaaaaaak! Krrraaaaaak!’ they cackled, flapping their wings and snapping their beaks with mirth. ‘You think those are fish, do you? Very funny, Hyena, very funny! Are you sure you are a king, Hyena? Wouldn’t a king know these things?’

Then they turned to Hyena’s wife, who was now blushing with shame. ‘How on earth did you agree to marry this man?’ they croaked. ‘He doesn’t even know a frog from a fish!’ Knowing they were right, she hung her head. Her father, too, hung his head, realising he had been tricked into arranging such a ridiculous marriage. ‘No wonder a bird has never married an animal,’ he muttered. ‘Those with feathers should stick together.’

Hyena, realising he had been found out, slunk off to live in hills far away, where he could hide. He’s never tried fishing again. For even now, if he goes near water, you’ll hear the herons mocking him. ‘Kwaaak, kwaaak, caught a frog?’ you’ll hear them cry. If you ever wondered why hyenas slink around ashamedly, now you know why.

There are several variations on this story – one about a man who marries a meerkat (which steals all his eggs and chickens at night), another about a woman who marries a cow (which spends all day ploughing fields for no reason) and another about a woman who marries a dog (which spends all night scavenging rubbish in the dump until it is shot). They are told in every southern African country.

Told to me in Shona by Justice Chinamhora in Harare, Zimbabwe

In the days when the earth was young, Hare and Cockerel were good friends and lived opposite each other at the edge of the kraal. Cockerel and his wife Mrs Hen roosted on the roof of a hut from which Mr Cock crowed every morning to tell the creatures that dawn had broken. And Hare and his wife had a burrow nearby, which they had dug deep into the ground to keep their ten baby hares cool.

The two friends were seldom apart. When Hare hunted in the long grass, Cockerel trailed behind him, pecking up insects that his friend’s legs had disturbed. At dusk, they would dip their heads down together at the river, sipping the cool water. And occasionally, Cock even shared with Hare some pieces of maize he’d found in the fields. Generally, though, it was Hare who was the boss, being the cleverest animal around.

One day, when Hare came to see his friend, Cock was doing what all cocks do when they rest: he was standing on one foot with his head under his wing. Hare had never visited Cock before when he was resting and was horrified. With eyes wide, he hopped round the hut, calling out to Cock’s wife. ‘Mrs Hen, Mrs Hen,’ he shouted, his whiskers twitching with excitement. ‘I went to see your good husband the Cock, but half of him was missing. His head has gone! And one of his legs!’

Mrs Hen was most amused that Hare was all a-twitch, because normally the vain creature knew everything. ‘What Mr Hare?’ said Mrs Hen. ‘Do you mean you can’t do that? Obviously my husband is a much cleverer creature than you. When he fancies a rest, he just sends off his leg and his head to do his hunting for him while he stays behind at home in the shade. I’m surprised you don’t do that, too, Mr Hare. Perhaps you aren’t so clever after all.’

Hare didn’t like being looked down on by a mere kraal chicken and would have liked to have given the clucky Mrs Hen a sharp kick with his back legs. But, being a crafty creature, he merely said: ‘Of course I can do that old trick, Mrs Hen. I just hadn’t realised that Cock could too. I would be delighted if, when Cock’s head is back from hunting, you both came over to my house for a drink to witness my own ability to do the same.’ With a haughty little kick, he leapt off into the air, and in a couple of bounds was home.

Back in his burrow, he immediately told Mrs Hare about his discovery. ‘Do you know that, while Cock is resting in the shade, one leg and his head are out hunting for him?’ said Mr Hare. Mrs Hare shook her floppy ears. ‘Anyway, I have decided that when the pair of them come for a drink later, I will have to show him that I, too, can do the same. After all, I am the cleverest creature in the land. Prepare the beer, and get out the axe, Mrs Hare, for we are about to show Cock not to be so cheeky with me!’

The timid Mrs Hare couldn’t believe her ears. ‘I couldn’t possibly chop off your head, my darling Hare,’ she said. ‘Who will look after our ten babies? Who will find me soft, nourishing roots to eat? And who will help me extend our beautiful burrow?’ But Hare was adamant. ‘Mrs Hare,’ he said sternly, looking down his nose at his pretty little bunny wife. ‘Am I not the cleverest animal in the kingdom? If Cock can cut off his head for a while, then why shouldn’t I? Do as I say and cut my head off. Then when our guests arrive, greet them and feed them. When they are full, my head will be back from hunting.’

Sighing, Mrs Hare picked up the axe and with one big swipe, she chopped off his head. ‘Now, off you go, head of Mr Hare,’ she said. ‘Get up and go hunting!’ But Hare’s head just lay there. ‘Hunt, head of Mr Hare, hunt!’ she ordered again, pointing her finger at her husband’s head. Still it remained motionless on the floor.

Just then there was a knock at the door. When Mrs Hare went to open it, there stood the fine-feathered figures of Mr Cock and Mrs Hen, ready for their drink. Mrs Hare didn’t know what to do, but, remembering her husband’s orders, she ushered the guests outside, sat them down, poured them beer and offered them some fine corn to snack on.

After one beer, Hare’s head was still not back. So she poured them another, then another, making excuse after excuse as to the whereabouts of her beloved husband. But eventually, she couldn’t bear it any longer, and crying huge bunny tears, she led them into the burrow where the late Mr Hare lay beside his head.

For once Cock wasn’t at all saucy and Hen didn’t cluck at all. All they could do was to comfort the widowed Mrs Hare and explain how Cock rested his head naturally with his head beneath his wing, before sadly going home.

As Cock crowed out the next day, he told the animals of the tragedy: ‘Wisdom doesn’t come from the eye, but from the brain,’ he said. ‘If Hare had bothered to think, rather than just look, he might be here today. But sadly, he didn’t use his head, so he lost it. Hopefully, you animals will not do that.’

The animals learned a valuable lesson that day, which they still remember: don’t always believe what you see. Think first.

Told to me in Nyemba by John Zulu in the Luangwa Valley, Zambia

A long time ago, when the earth was young, the Great Spirit looked down and was pleased. The trees he had planted grew tall and lush, the rivers he had filled ran with fish big and small, and the men he had created were working hard in their fields. ‘I think the humans deserve a reward,’ he said. ‘They have tended their crops, worked hard and lived peacefully together. I will send a message to make them happy.’

The great god rumbled his thunder, darkened his clouds and called out to the chameleon, who he often used as his messenger. ‘Chameleon,’ he thundered, ‘I have a very important message for Man. Tell him that I am so pleased with him that he will never, ever die. He will live for ever.’

Chameleon was rather pleased at having been chosen to be the god’s messenger. ‘So, Man will never die,’ he said, swaying self-importantly from side to side. ‘Now there’s a special message to take. Gosh, I am an indispensable fellow.’

As he ambled slowly from branch to branch, his scaly green eyes swivelling in their sockets, Chameleon chanced upon a whole crop of insects, his favourite food. ‘With such a feast in front of my eyes, how can I resist?’ he said, settling down to snack on a fat juicy insect. One, of course, wasn’t enough, and before he knew it the afternoon had turned to night. ‘Well, Man’s waited so long, I’m sure another day’s wait will not harm,’ he said, rocking gently towards a branch and rolling back his eyes for a good night’s sleep. ‘Good night, green forest, Good night.’

While Chameleon was having a marvellous feast, the Great Spirit was getting increasingly cross. The men he’d seen tending their crops that morning were now drinking, letting their animals wander, and fighting with their neighbours – all things he’d forbidden them to do. ‘I am mistaken,’ rumbled the god. ‘Man must die after all.’

Again the Great Spirit rumbled his thunder, darkened his clouds and called out to Lizard, another regular messenger. ‘Lizard,’ he thundered. ‘I have a very important message for you. Tell Man I am very displeased with him. So displeased, in fact that I have decided that he will have to die after all. He will not live for ever.’

The little lizard, being a nervous fellow, immediately dashed off, thrilled that the great god had noticed him. ‘What a terrible thing,’ he said, whisking his tail in the air. ‘I must hurry and warn Man.’

Within hours Lizard had leapt over logs, scuttled under stones and dashed along dusty paths to the village where Man lived, without stopping to eat or even have a drink. ‘Man, oh Man,’ he said, his little tongue flicking out dryly. ‘I’m afraid I have terrible news. The Great Spirit is very displeased. He says because of your laziness and violence, rather than having everlasting life, you will die.’

Naturally, Man was very upset. But it was too late to be sorry. He had done wrong, and now it was time to pay. Great unhappiness set upon the village, and when Chameleon arrived, the air was thick with weeping and wailing. ‘Oh, stop this crying and everyone gather round,’ shouted Chameleon self-importantly. ‘I am the official messenger of the Great Spirit and I have extremely important news.’

Slowly and self-importantly Chameleon told them his message. When he’d finished there were great songs of joy. ‘We will not die after all,’ the villagers sang, their drums ringing out in celebration. Then Lizard stepped forward. ‘Excuse me, Mr Chameleon,’ he stuttered nervously. ‘But on which day were you given the message?’

Chameleon stepped from foot to foot, umming and aahing and nervously rolling his eyes. But when at last he told the truth – that in fact he had not just stopped for a feast of radiant bluebottles, buzzy mosquitoes and fat horseflies, but had stayed in the jungle for the night – the humans were furious. ‘If you weren’t so greedy,’ they shouted, ‘we would have lived for ever. It is because of you, fat Chameleon, that we will now die.’

Chameleon was so embarrassed he wanted to vanish into the background. He shook, he stuttered, and he puffed himself out in terror, but still Man stood there shouting at him. Eventually, the Great Spirit took pity and granted him the ability to the change colour of his skin to match his surroundings when he needed to. From that day on, he’s been able to vanish at will. Man, though, will never forget the cursed creature and knows that, whenever he sees a chameleon, bad news is just around the corner.

Told to me in Ndebele by Emma Matshazi in Bulawayo, Zimbabwe

Once upon a time there lived a group of the greatest lizards ever known. These creatures were not just monstrous, but magnificent, with great, green slimy bodies, long purple fingers, forked pink tongues and tails so strong they could flick a cow into the water. If threatened, the creatures would gather together like a great army, shooting up terrifying folds of red skin around their necks, flicking their tongues and hissing like dragons. They were called the Inxou.

The Inxou lived on the banks of a large river. By day, they would lie on rocks, sunning their scaly bodies, while their babies splashed and played in the water. At night, they would curl up in a forest, close their yellow eyes and emit loud steamy snores as they slept. No matter how well they slept, though, they would always be on the alert for their deadly enemy, Man.

Man was terrified of the dragon-like Inxou. But he was also entranced by it, because it had magical healing powers that no other creature possessed. If a man got sick, eating the liver of an Inxou would make him better. If a woman’s baby died, chewing the liver of an Inxou would take away her grief. Every witch doctor in the country wanted the liver of an Inxou for his medicine box. Very few were brave enough to catch one.

In a village near the river where the Inxou swam lived a man and his wife. One day the wife fell very ill, but no matter how hard the witch doctor threw his bones, summoned the spirits and stirred up a potion of herbs, she wouldn’t get better. ‘There is only one cure,’ the witch doctor eventually pronounced. ‘You must mix these herbs with the liver of an Inxou. Do that and your wife will get well.’

The man was very scared. He had heard terrible tales of the terrifying Inxou. But he loved his wife and wanted to save her. So that night he lay in bed and thought of a plan.

The next morning he went to visit a brave warrior who long ago had killed a ferocious Inxou himself. ‘Please my friend may I borrow your Inxou skin?’ he begged. ‘If I look like an Inxou, and live with the Inxou, I might have a chance of catching an Inxou.’ The warrior agreed and together they covered the man with the Inxou skin, tying the lizard’s front legs to the man’s hands, and its back legs to his feet. How ferocious he looked on all fours! ‘Those dragons will never know it’s a man!’ the warrior laughed.

The next day, the man set off on his mission, disguised as a lizard, and carrying a bag of beans, which he knew the Inxou loved. At last he reached the river, and in a lizardy voice cried out: ‘My friends, my friends! I have a treat, I have a treat! Come and join me for a feast!’

The lizards looked at him suspiciously, as they didn’t recognise this strange Inxou. But he had the scales of an Inxou, and the legs of an Inxou. And he had their favourite treat of beans. So they welcomed him and were soon feasting on their new friend’s gift.

One day, as the man was lying on a rock watching the grandmother, a baby Inxou began to stare at him suspiciously. As the baby looked at the man, it began to sing a song. ‘What type of animal are you?’ it sang, ‘What kind of animal are you? With hands and head like a man, but the body of an Inxou?’

The man started to shake, worried the other lizards might hear, but no one took any notice but the baby’s parents who told it to be quiet.

But the baby took no notice and this time started to sing more loudly: ‘What type of animal are you? What type of animal are you? With hands and head like a man, but the body of an Inxou?’

Before the parents could look at him more closely, the man scuttled off into the forest on all fours. ‘Oh no!’ he thought as he waddled away. ‘My disguise has been discovered. I am going to have to catch the grandmother tonight.’