Two

BECOMING AMERICA’S SPA

Largely through the promotion and zeal of Stephen T. Mather, the first director of the National Park Service, Congress redesignated Hot Springs Reservation as Hot Springs National Park on March 4, 1921. The popular park was by this time a world-famous destination for not only those seeking cures for various ailments, but for people looking for simple relaxation and enjoyment in a resort environment. A trip to the grand establishments along Bathhouse Row was considered essential for restoring good health and vitality to life. The tremendous influx of patrons, however, not only changed the services that were offered, but altered the face of the park itself.

The progression of government-owned free bathhouses would culminate with the opening of a state-of-the-art facility in 1922. (This would later become known as the Libbey Physical Medicine Center.) In the 1930s, the park service would perfect an efficient thermal water-collection system, featuring large underground-holding reservoirs and an elaborate pumping network, allowing plenty of thermal springwater to be available to all the bathhouses calling for it. A new facility to house the park maintenance division would be erected on Whittington Avenue in the mid-1930s. Work would begin on the Grand Promenade on the hillside behind Bathhouse Row, from Reserve Street in the south to Fountain Street in the north. A new park Administration Building would replace the old Superintendent’s Office at the corner of Reserve Street and Central Avenue in 1935. And, the stately Victorian Superintendent’s Residence on Fountain Street would be torn down to complete the wooded foreground at the north end of the Grand Promenade. But, the introduction of new medicines and therapeutic practices occasioned by World War II would portend great changes for the bathing industry in Hot Springs.

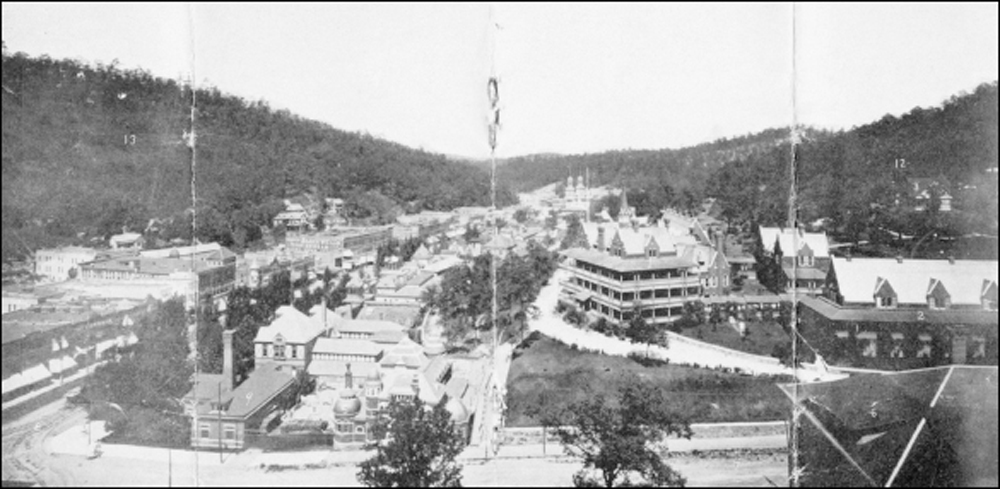

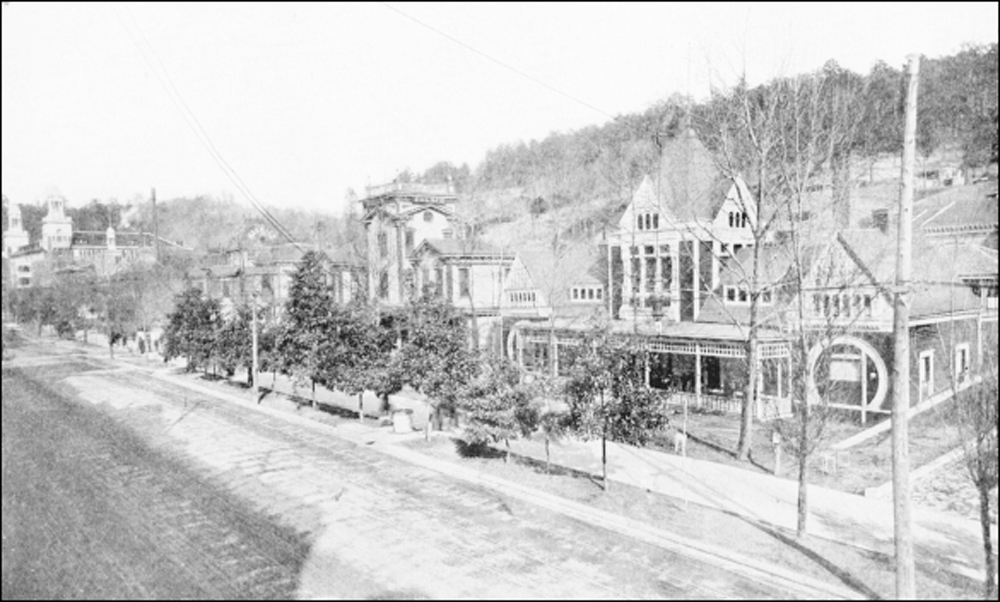

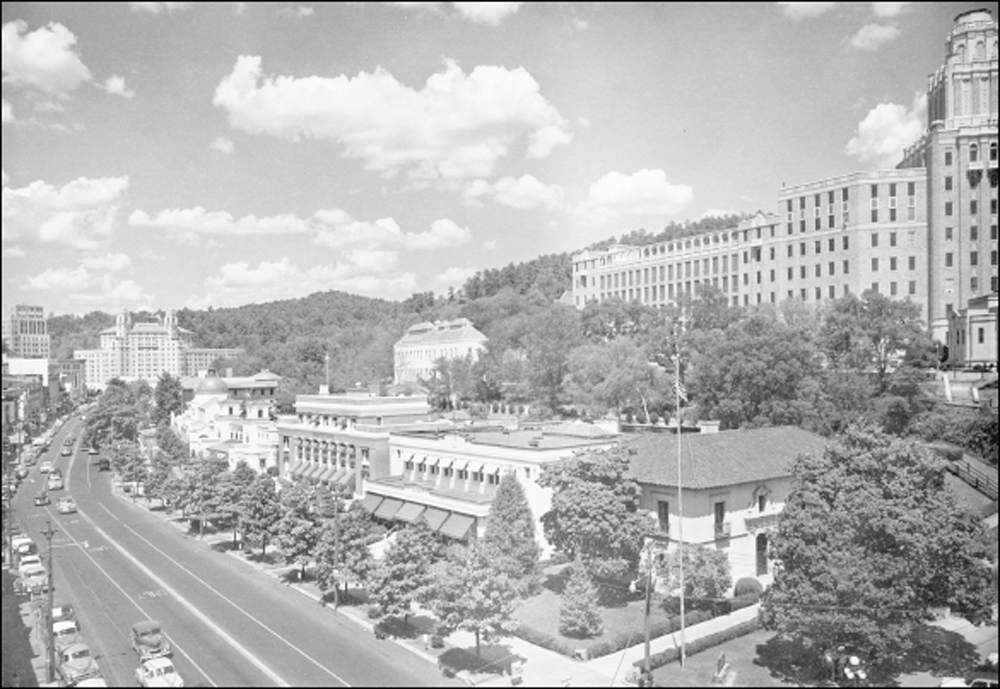

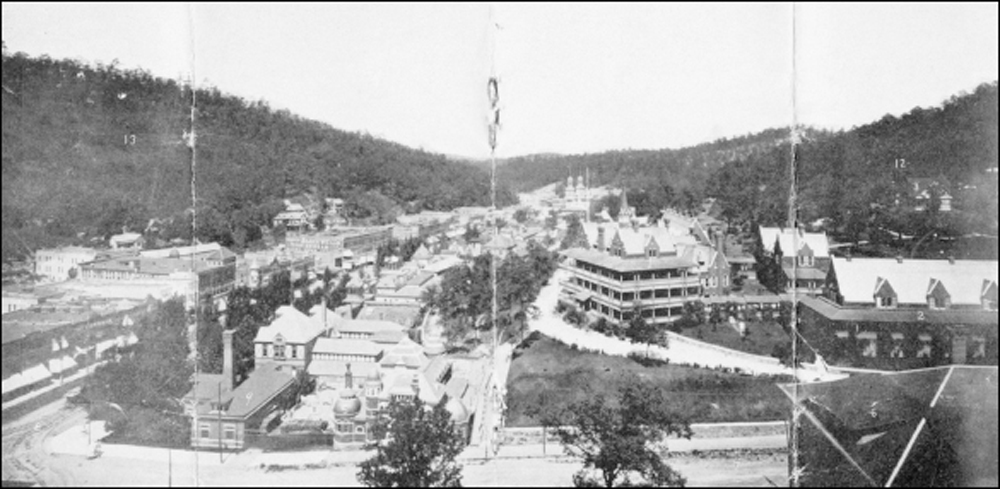

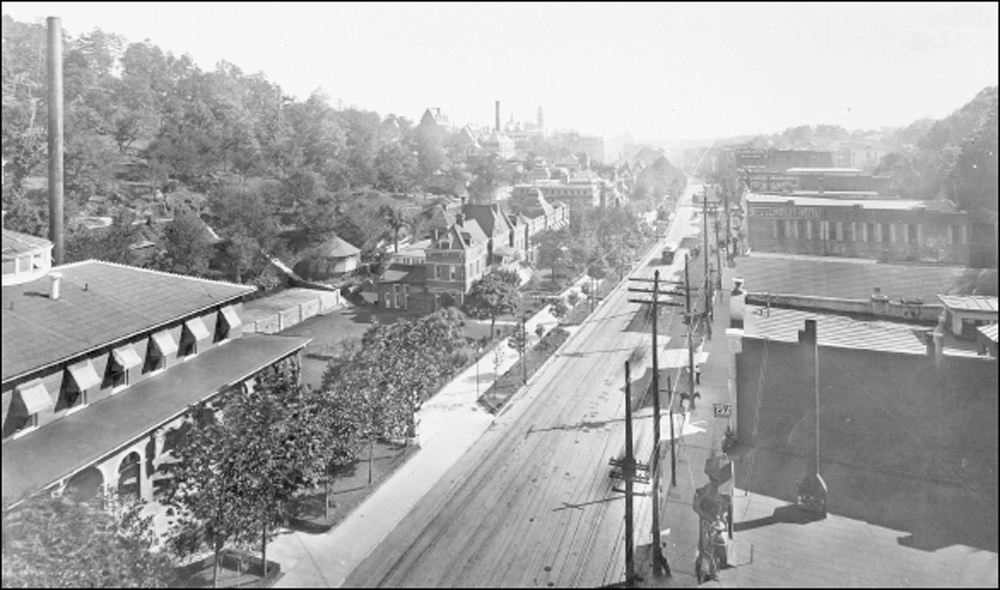

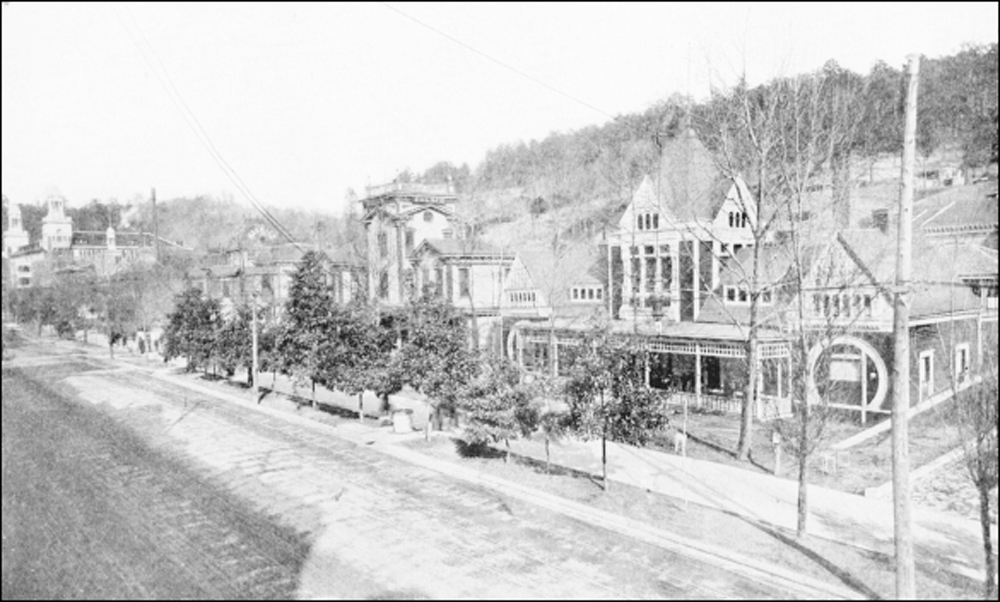

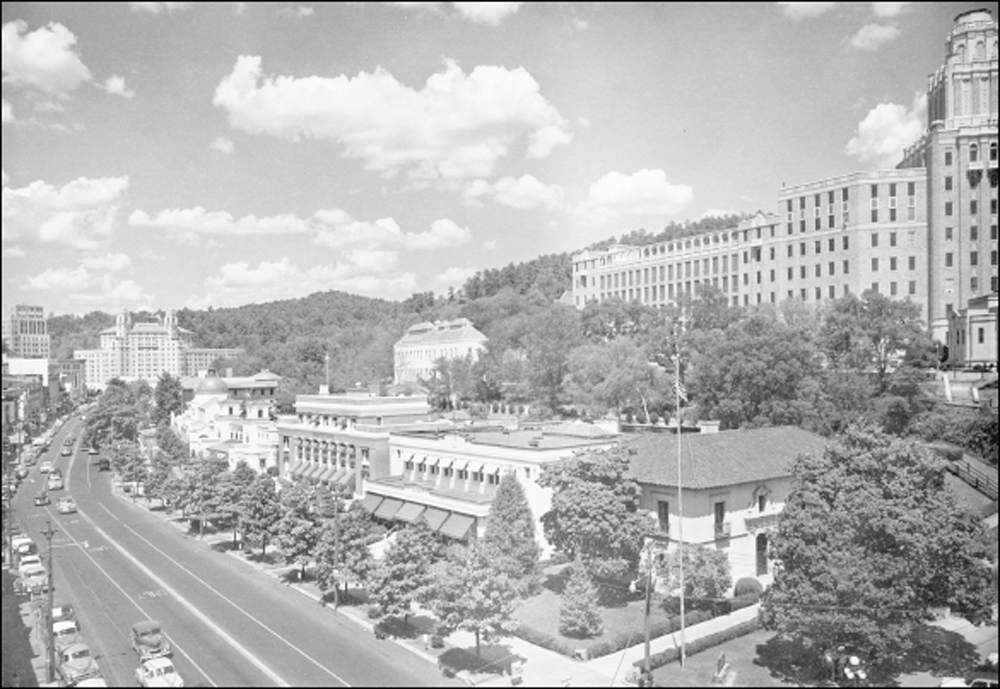

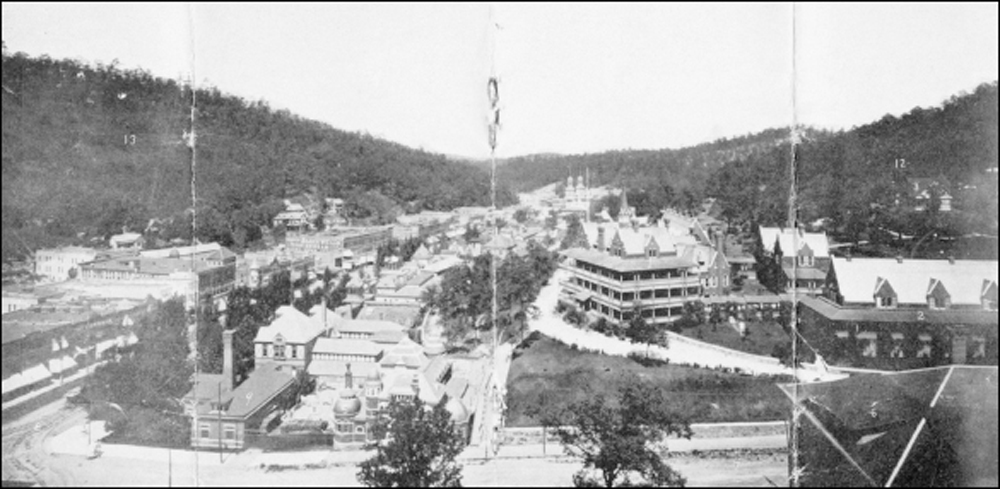

This panoramic view of Hot Springs from a tourist brochure, “Hot Springs in a Nutshell,” shows the expansion of the valley. Taken from the top floor of the Eastman Hotel, the photograph shows the Imperial Bathhouse with the Superintendent’s Office at the south end of the reservation. Visible behind them are the Lamar and Rammelsberg Bathhouses. The second Arlington Hotel is at the far end of Bathhouse Row.

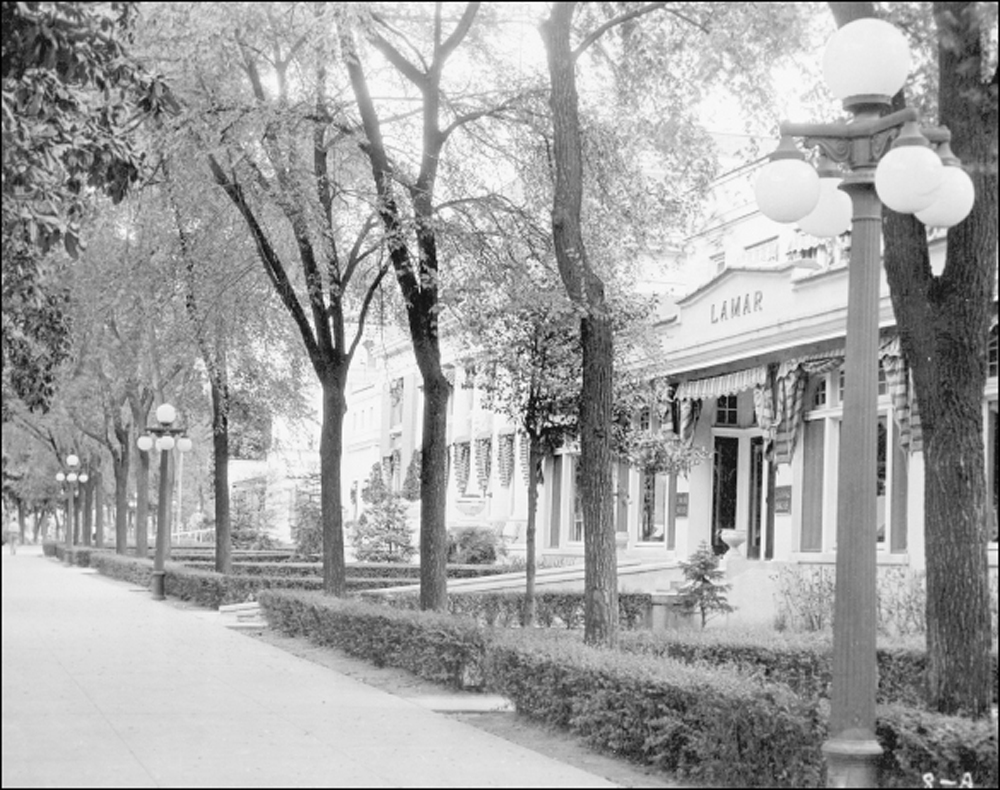

The first version of the Maurice Bathhouse was a Victorian wooden building with large windows in the lobby. The long walkway and wide expanse of sidewalk were installed after Hot Springs Creek was covered with an arch. Three rows of trees were established between the buildings and the street, the last being the magnolias.

The sun porch at the first Lamar Bathhouse was narrow and often crowded with customers waiting for their time in the baths. Although it was supposed to be a place to relax, these patrons look anything but in the congested space. Note that the women are at the far end, away from the men with cigars.

Samuel Fordyce’s Palace Bathhouse, built in 1888, was a step above many of the other businesses. Situated on the site of the New Central Bathhouse, the Palace was stocked with porcelain tubs for the bathers’ comfort. Operating until the end of 1913, the building was torn down and replaced with the new Fordyce Bathhouse.

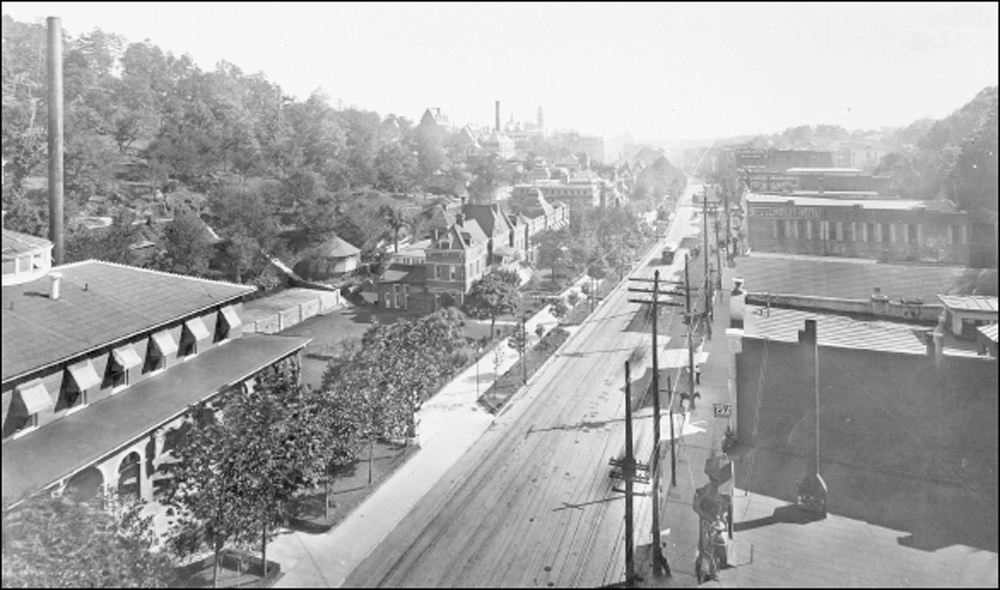

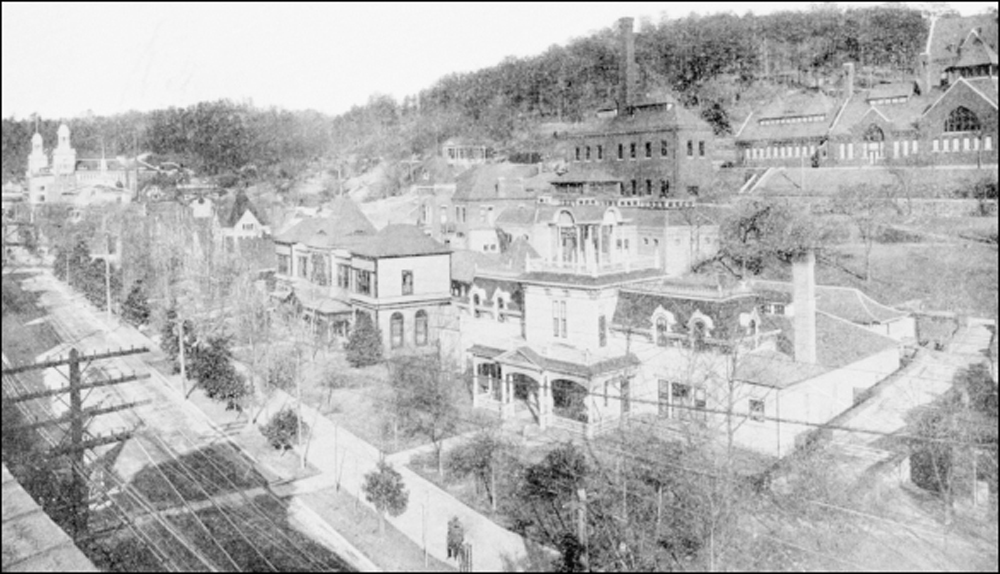

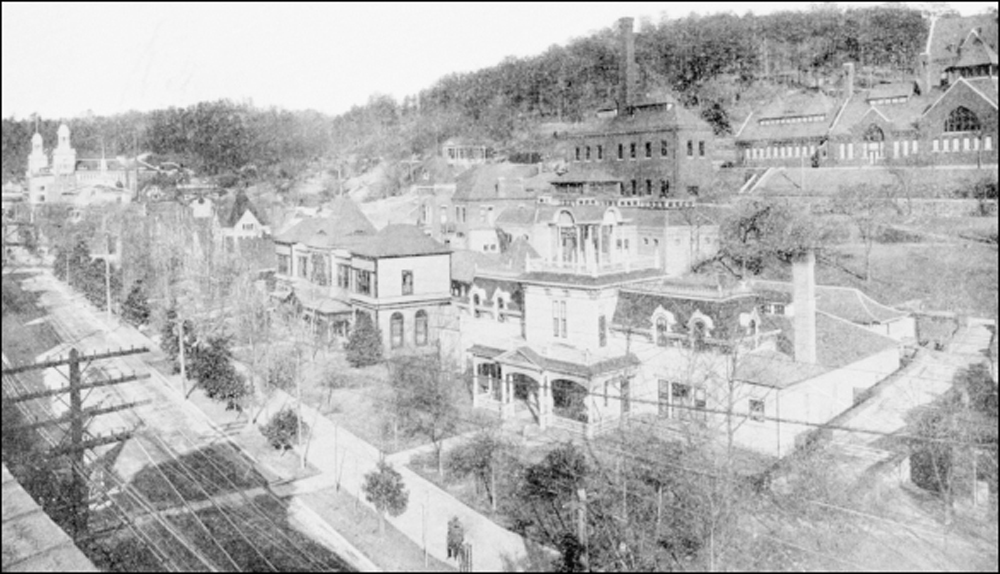

Starting with the second Arlington Hotel (left foreground), changes are apparent in the park in 1911. The absence of the Rector Bathhouse has left a green space next to the Superior, and cooling tanks are visible behind this bathhouse. Next is the Old Hale, with its name printed on its domed roof, followed by the second Maurice, which is under construction. Horses and trolleys run on Central Avenue.

In 1892, the old Rector on the east side of Central Avenue was demolished to make way for the new Arlington Bathhouse. A new Rector (right) opened on the west side of the street in 1895. The bathhouse was outfitted with men’s and women’s parlors and had a connecting bridge to the Waukesha Hotel next door.

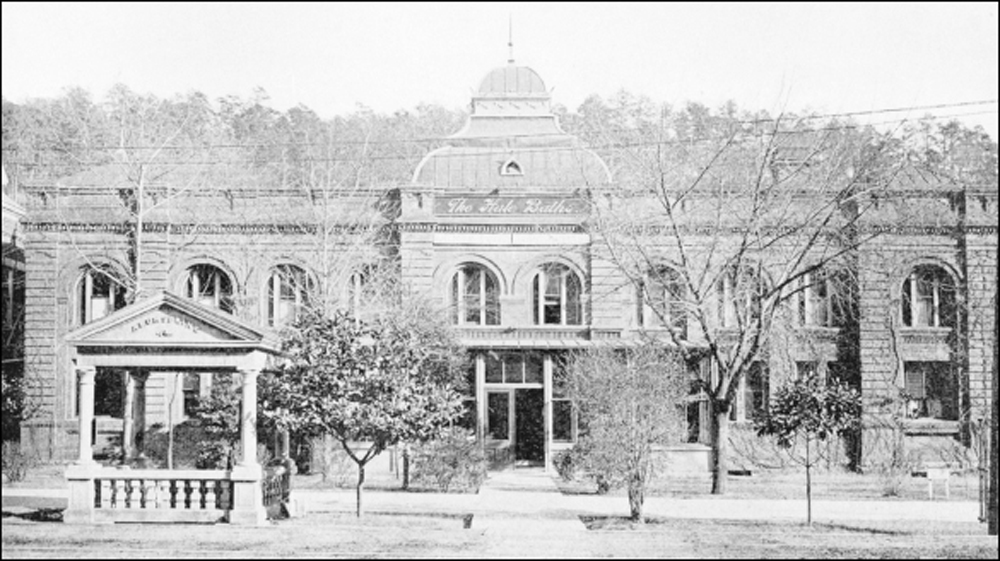

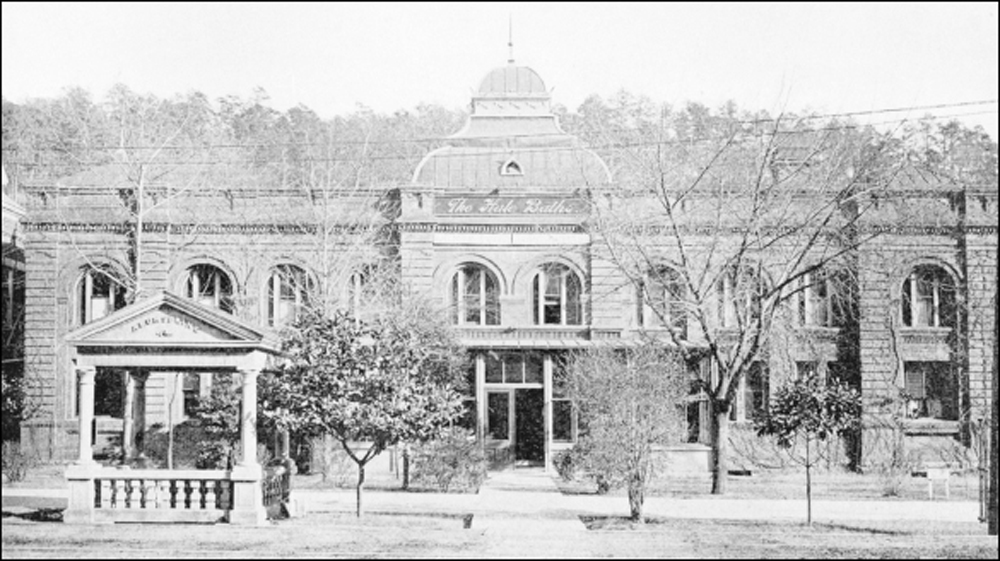

A Grecian pavilion built in 1897 sits atop Alum Spring in front of Hale Bathhouse. The pavilion would later be renamed the Major Harry M. Hallock Fountain after the reservation medical director who served from 1909 to 1913. The spring was covered in 1921 as part of renovations in the park. This fourth version of the Hale was completed in 1892 on the same site of the previous Victorian version.

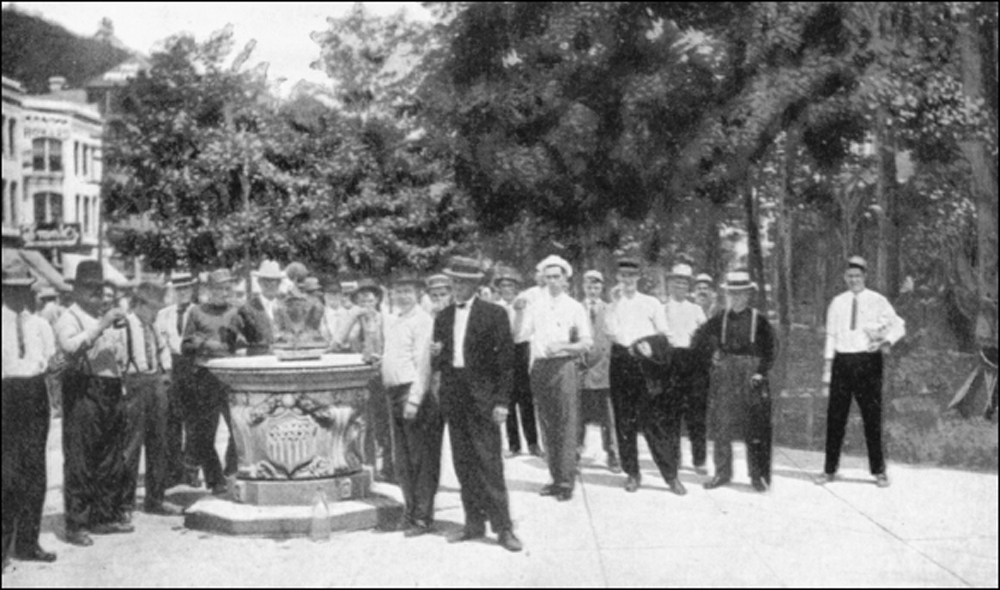

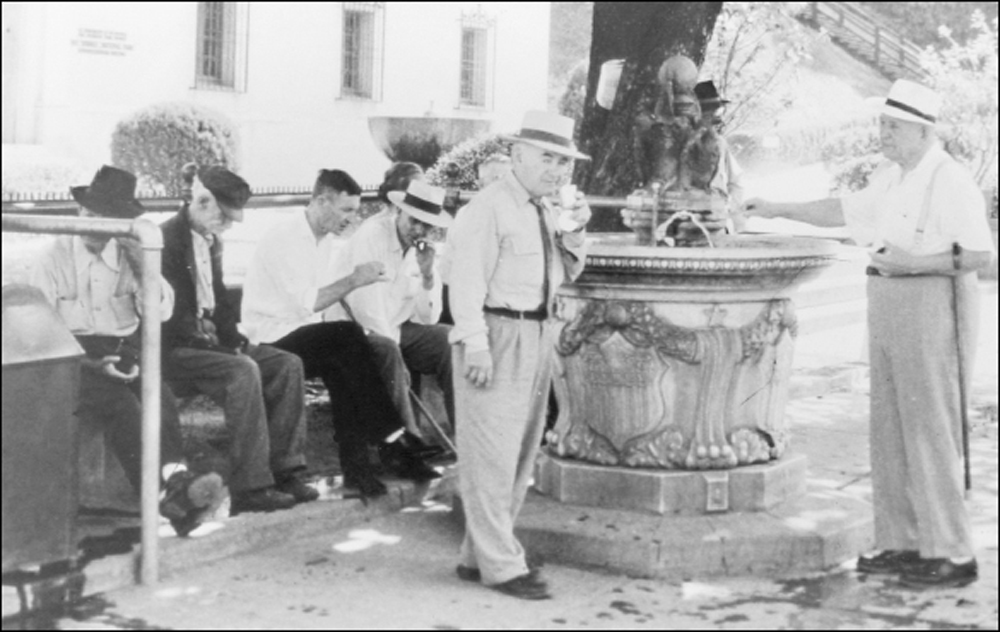

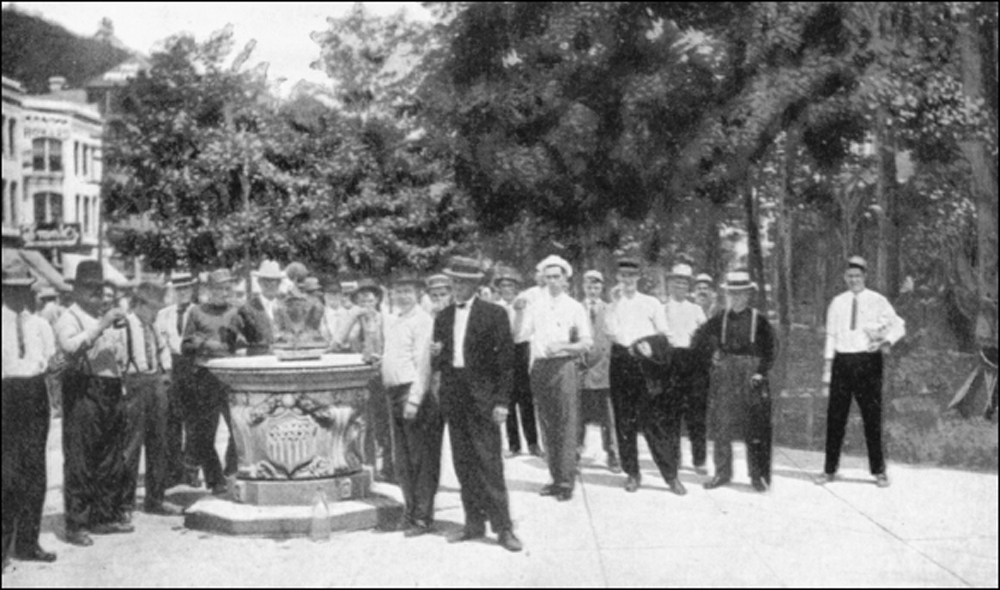

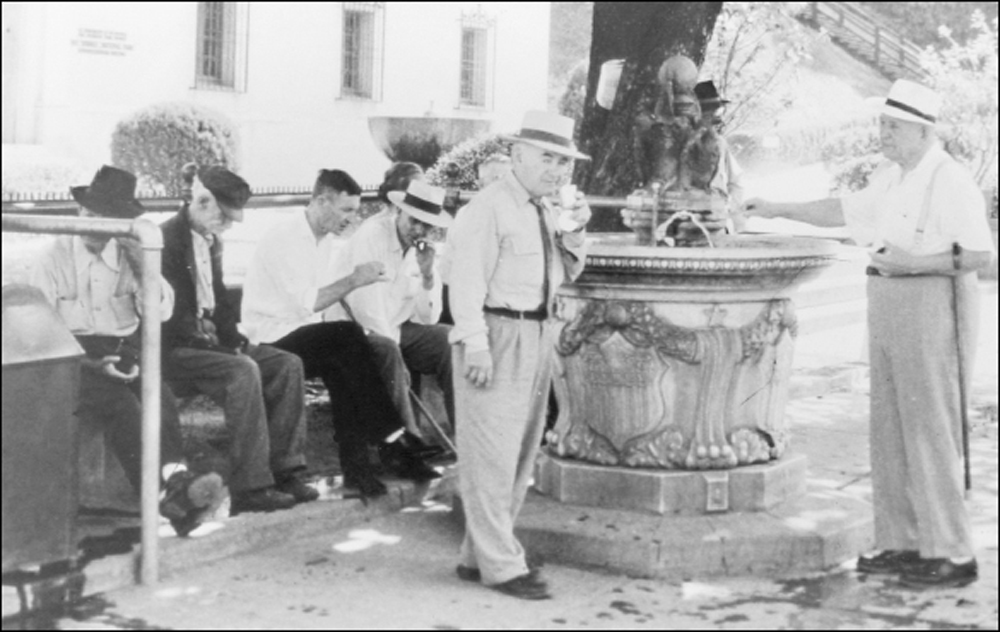

As visitors flocked to the resort, the park made changes to provide access to the thermal drinking water for everyone. Noble Fountain was installed at the south end of Bathhouse Row at the corner of Central Avenue and Reserve Street. Its bronze eagles were designed by the famous sculptor Edward Kemeys. This convenient location quickly became a gathering spot for locals and out-of-town guests.

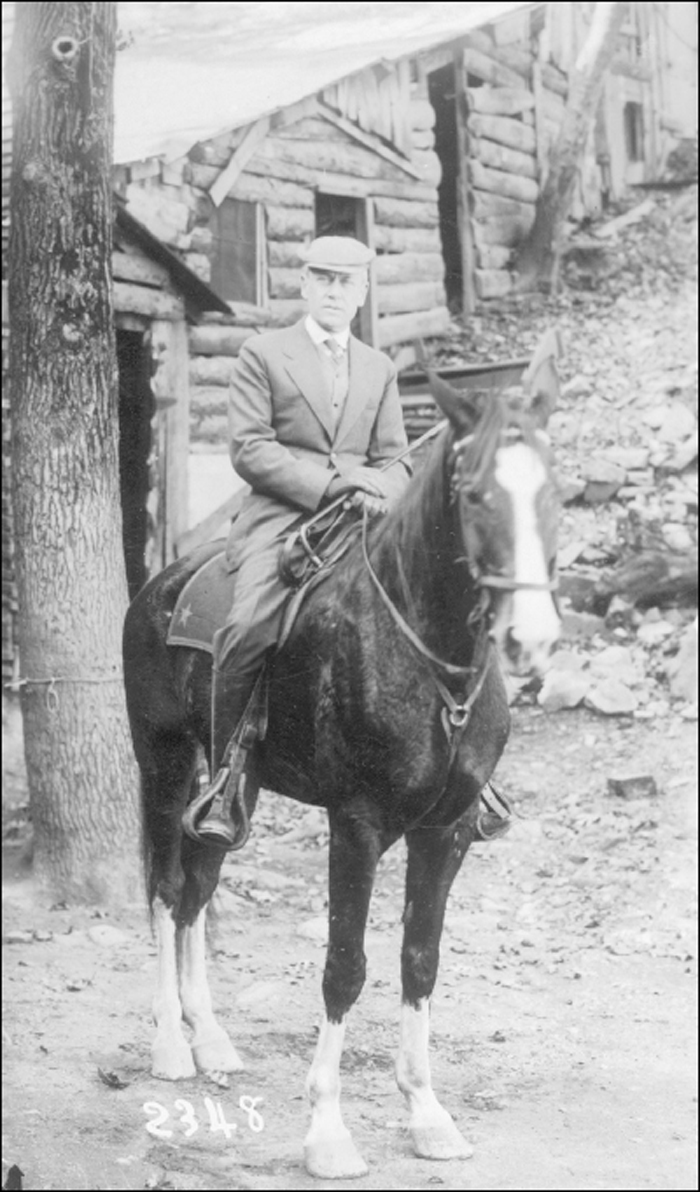

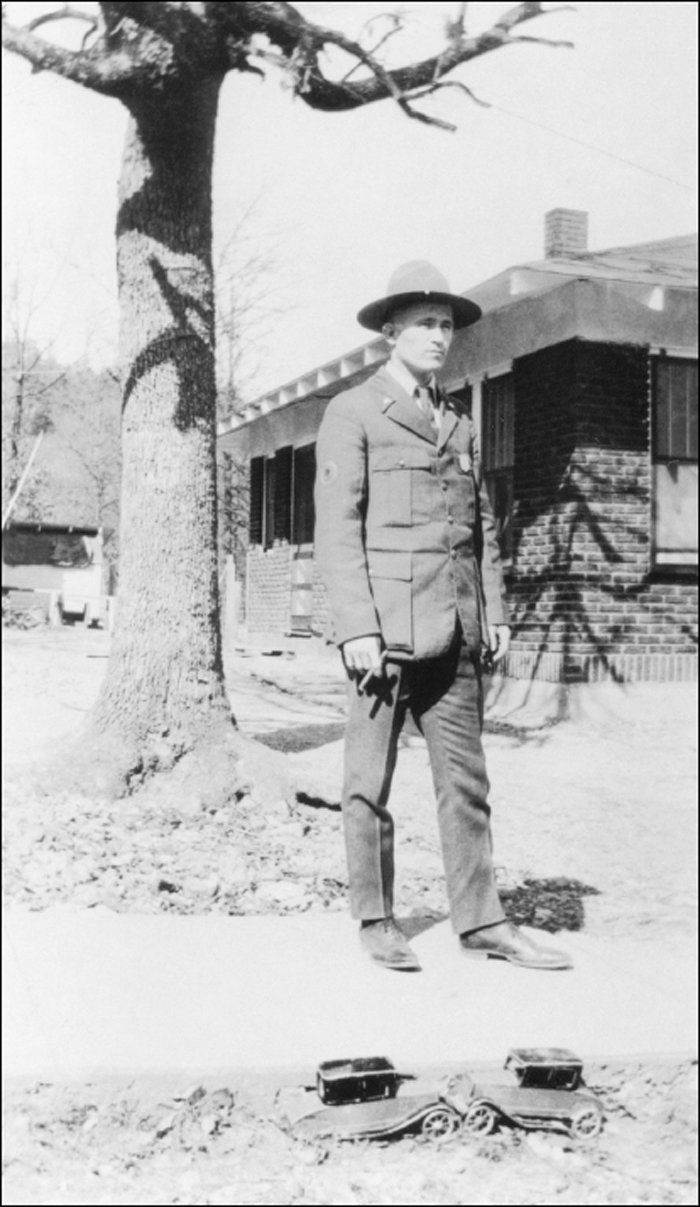

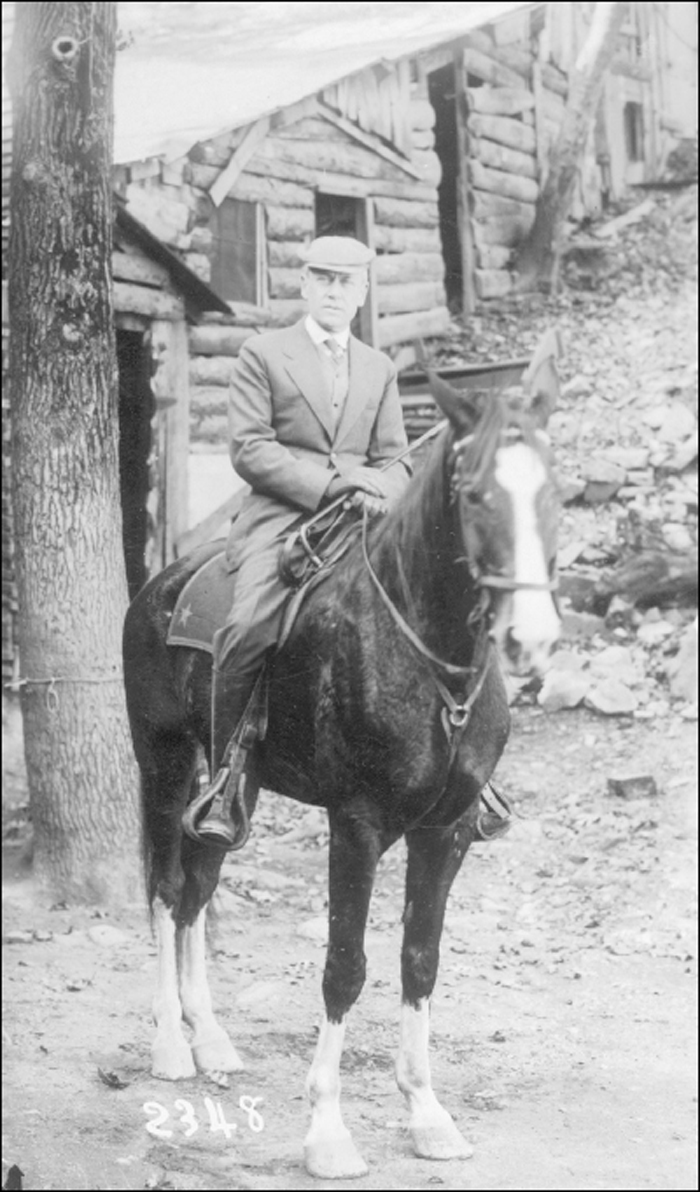

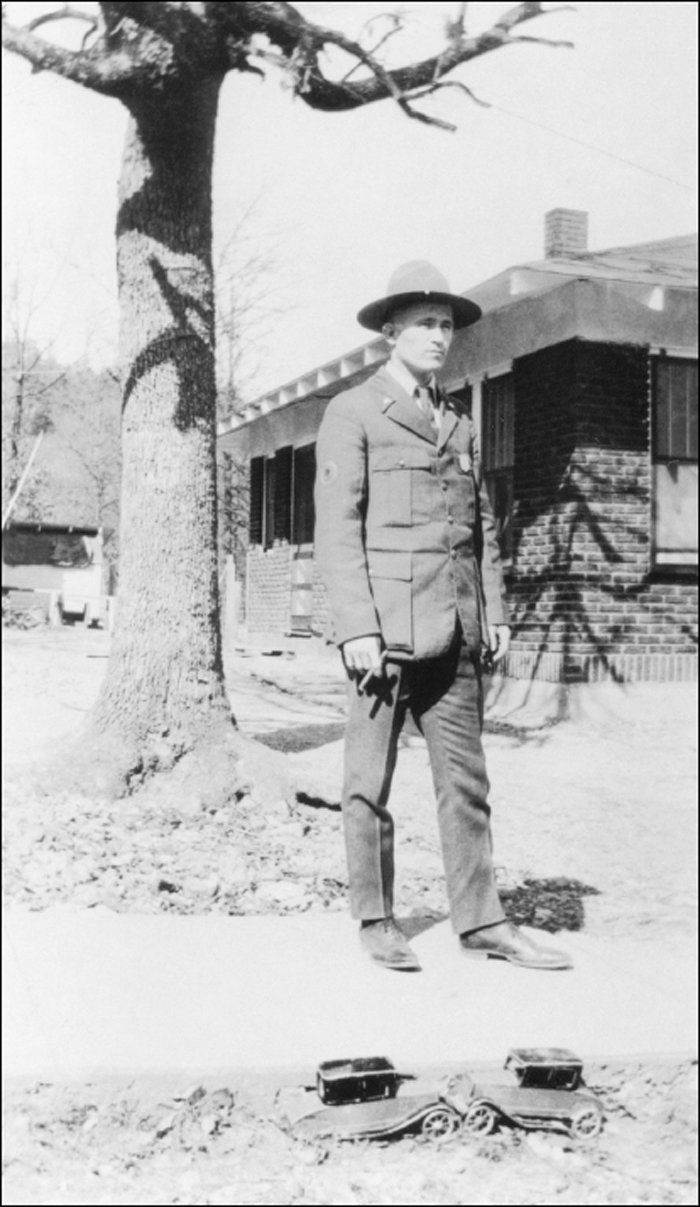

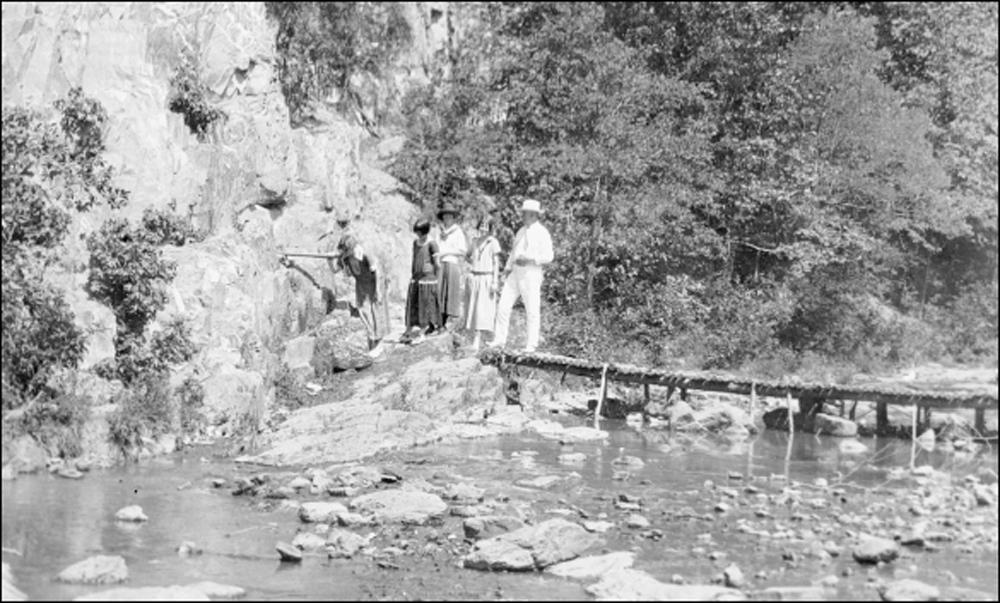

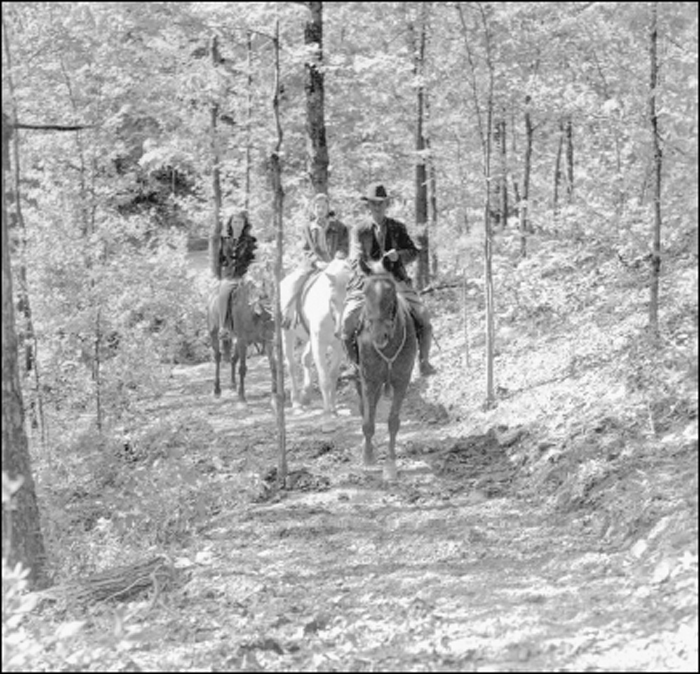

Assistant Secretary of the Interior Stephen T. Mather poses on horseback in Happy Hollow while visiting Hot Springs in November 1915. Mather was an enthusiastic supporter of Hot Springs even before he was named the first director of the National Park Service in May 1917. He showed a keen interest in the park’s affairs, even remarking that Hot Springs had not been “thoroughly appreciated” in the past. The fact that Hot Springs Reservation was renamed Hot Springs National Park by Congress in 1921 is directly attributable to Mather’s recognition of its importance and his political influence in Washington, DC. Unknown to many, Mather suffered for most of his adult life from bipolar disorder, enduring incapacitating stress-induced mood swings that periodically required his extended confinement in a sanitarium or hospital. Afterward, he would quietly retreat to the majestic scenery of one of his beloved national parks to recuperate, surrounded by nature. On at least one of these occasions Mather came to Hot Springs to recover in the familiar confines of the Fordyce Bathhouse, where he bathed and relaxed with massages.

The Rammelsberg (left) and the Lamar together anchor the south end of Bathhouse Row. A sign on the Rammelsberg advertises 21 baths for the rate of $3. The roof of the Imperial Bathhouse is barely visible behind the Lamar. On the hill above is the Army and Navy General Hospital and, on the far right, the expansive Eastman Hotel.

Over time, Bathhouse Row was being slowly molded into a more park-like setting. The magnolia trees along the street were planted in 1893 and 1894. The buildings lining the street are, from near to far, the Horseshoe, with its distinctive white circular window trim, the Palace, and the Maurice. At the far left end of the street is the second Arlington Hotel.

With its imposing facade, the Ozark Bathhouse towers over its smaller neighbor, the Magnesia. Since its original construction in 1880, the Ozark had been renovated to install tile floors and fashionable porcelain tubs. The top floor and rounded roof of the Government Free Bathhouse can be seen behind the Magnesia.

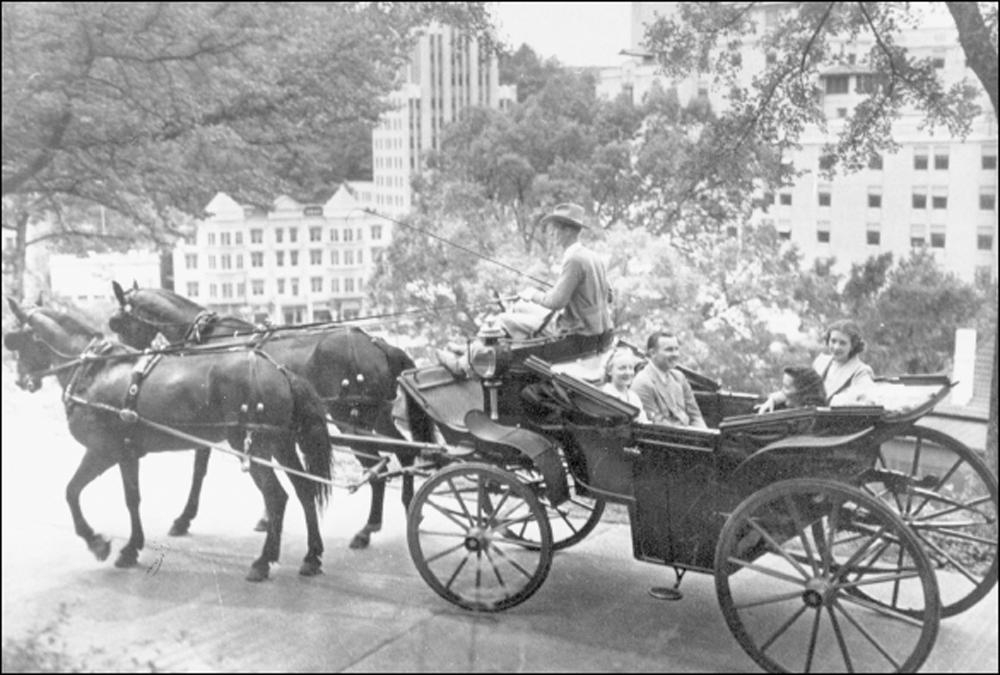

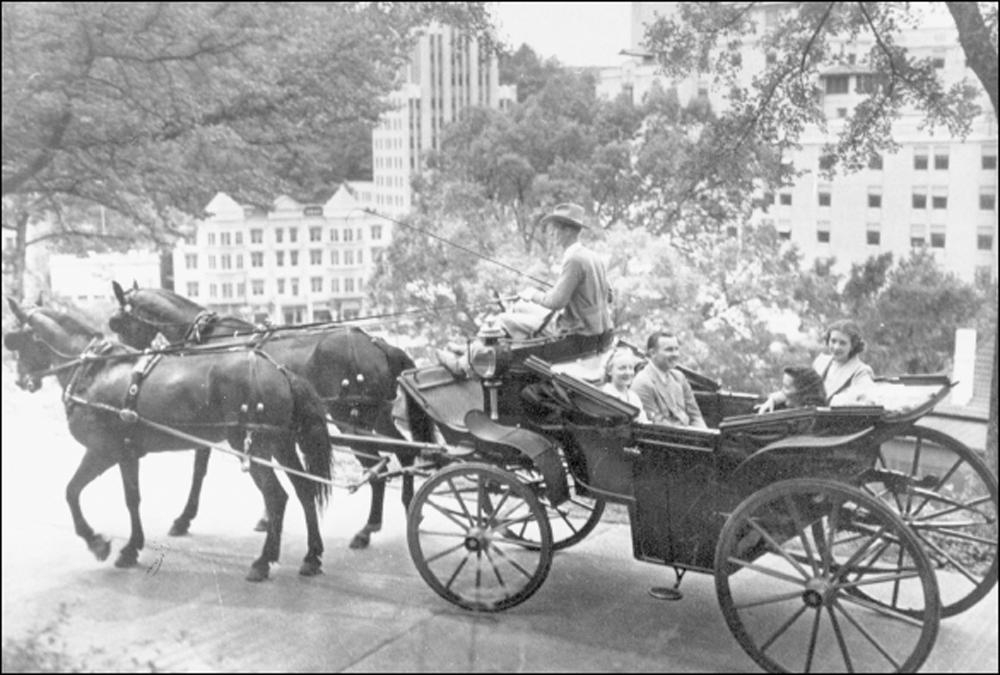

All of the members of this family ride together in a four-in-hand coach approaching Hot Springs Mountain. The sightseeing tours run by the Cooper Brothers Livery Stables took tourists up and down the gravel Pleasure Drive and Carriage Road, enabling them to enjoy the natural surroundings of the beautiful resort while in town to seek treatment for their health.

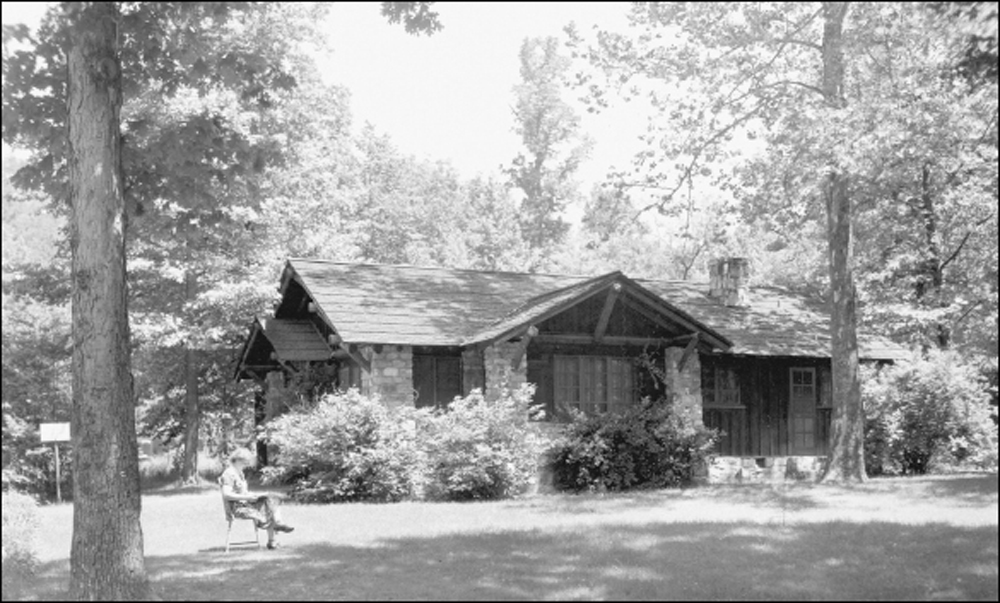

The Dugan family poses for a photograph in front of their residence, the Caretaker’s Cottage in Whittington Park. Patrick Dugan, a Civil War veteran, came to town for treatment of war wounds and later became the reservation forester. Posing here are, from left to right, John, Dan, Mary, Patrick, Billy, Maggie, Henry, and Jimmy. The cottage is in the background on the left, partially obscured by trees. (Courtesy of Jerome Michael Dugan.)

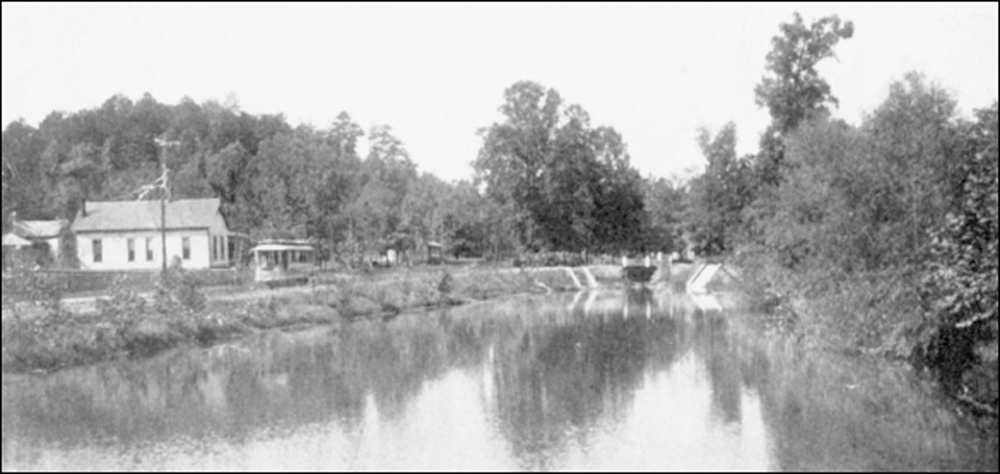

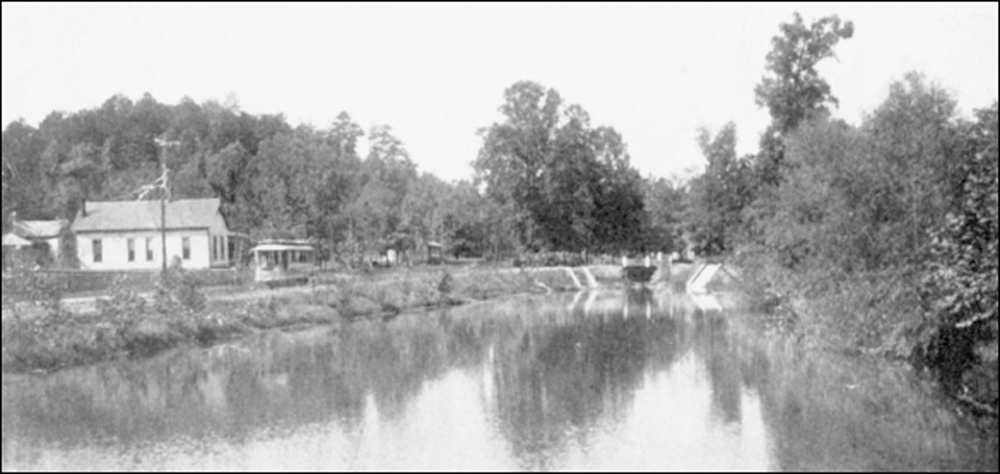

Initially called the Whittington Avenue Lake Reserve, this tranquil lake on the 11-acre Whittington Park site is seen here. A trolley passes on the left. Limestone posts were placed at the park’s entrance, and an iron fence enclosed the property. The fence was washed away during a flood in 1923.

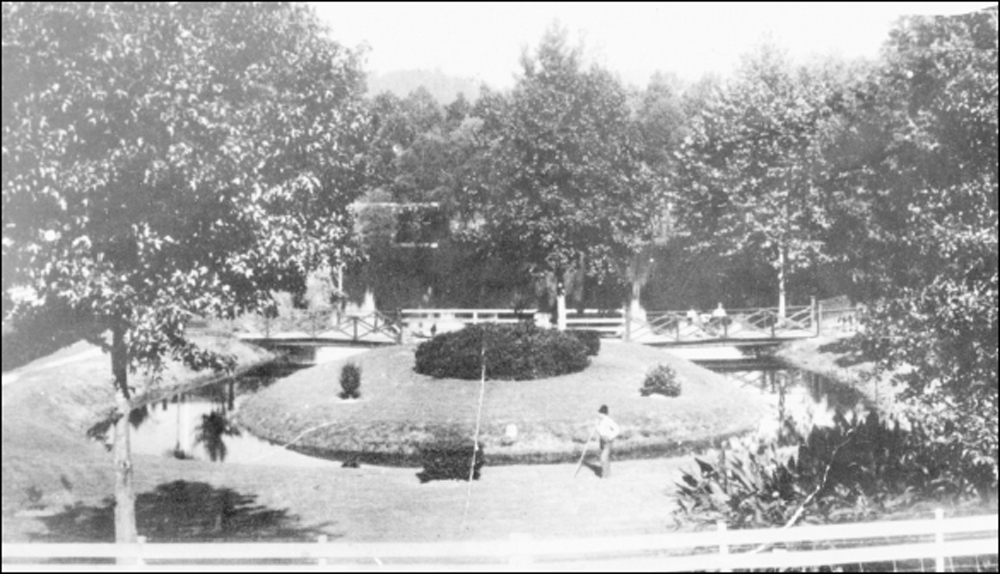

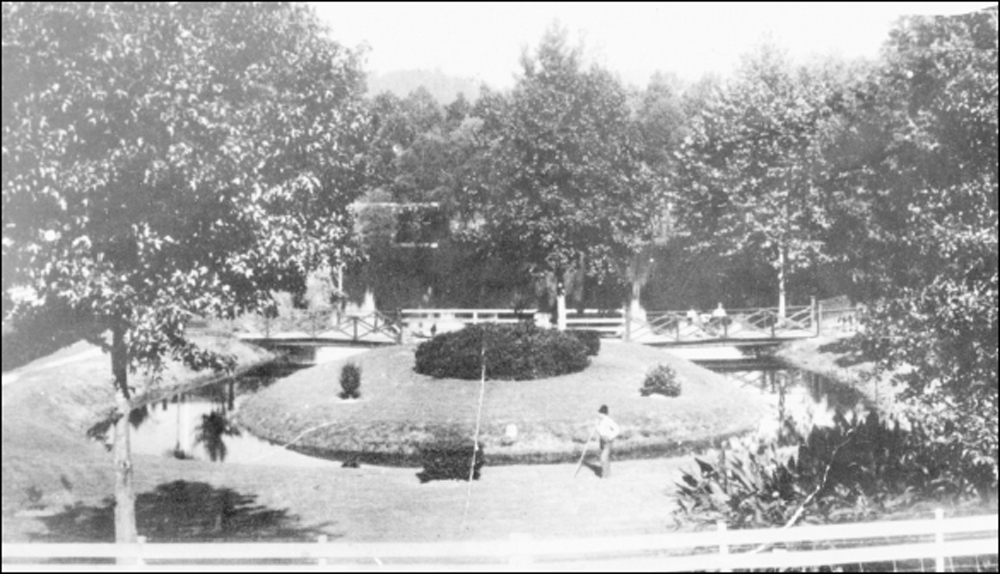

This photograph of the finely landscaped circular island between the lakes at Whittington Park shows one of the five bridges that were constructed across the lagoons. Water flow was a constant problem, and the lakes were eventually replaced with open expanses of lawn. Stone retaining walls enclosed the creek and helped alleviate erosion effects. (Courtesy of Garland County Historical Society.)

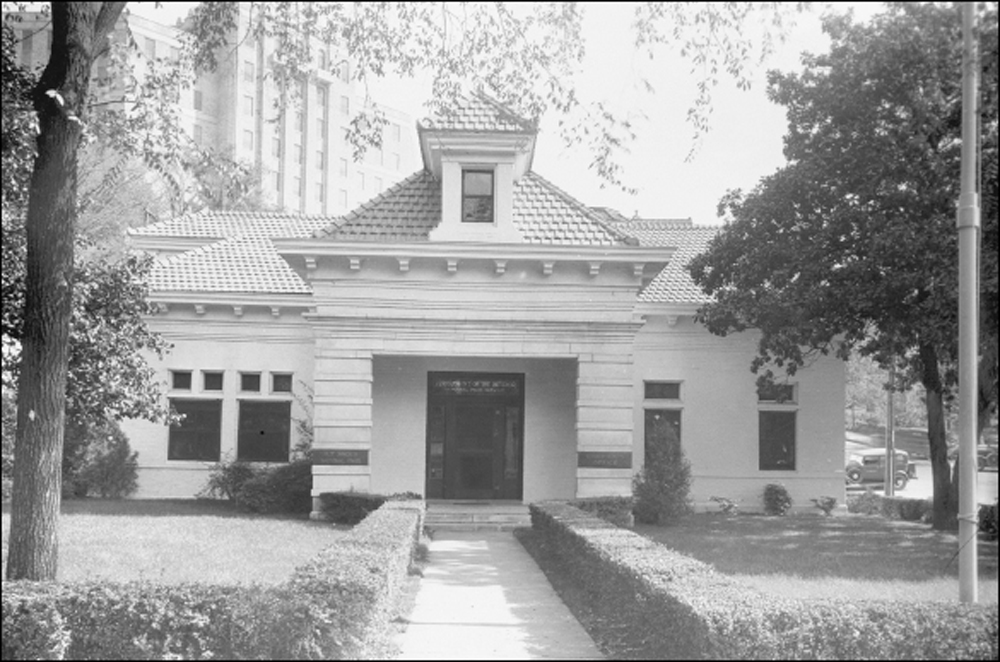

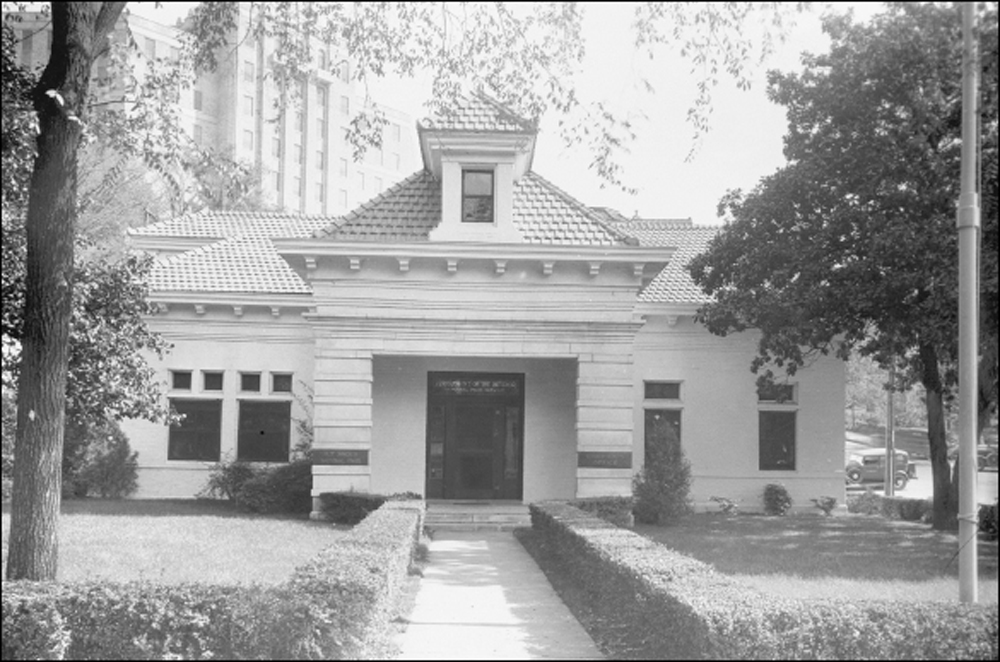

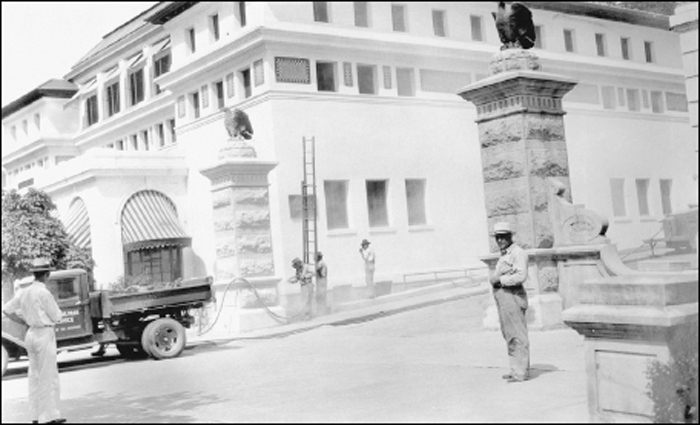

This photograph, taken after 1921, displays the name Hot Springs National Park on the left column of the Superintendent’s Office, located at the corner of Central Avenue and Reserve Street. The original building was constructed of brick and stone and painted white. Supt. William Little moved his office from the residence on Fountain Street to this building after it was remodeled in 1898.

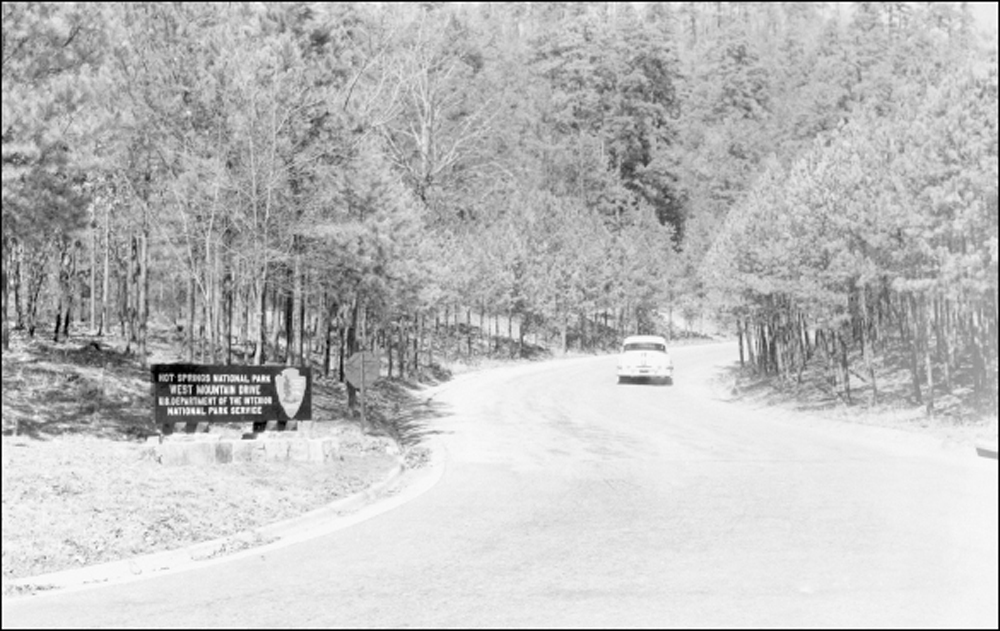

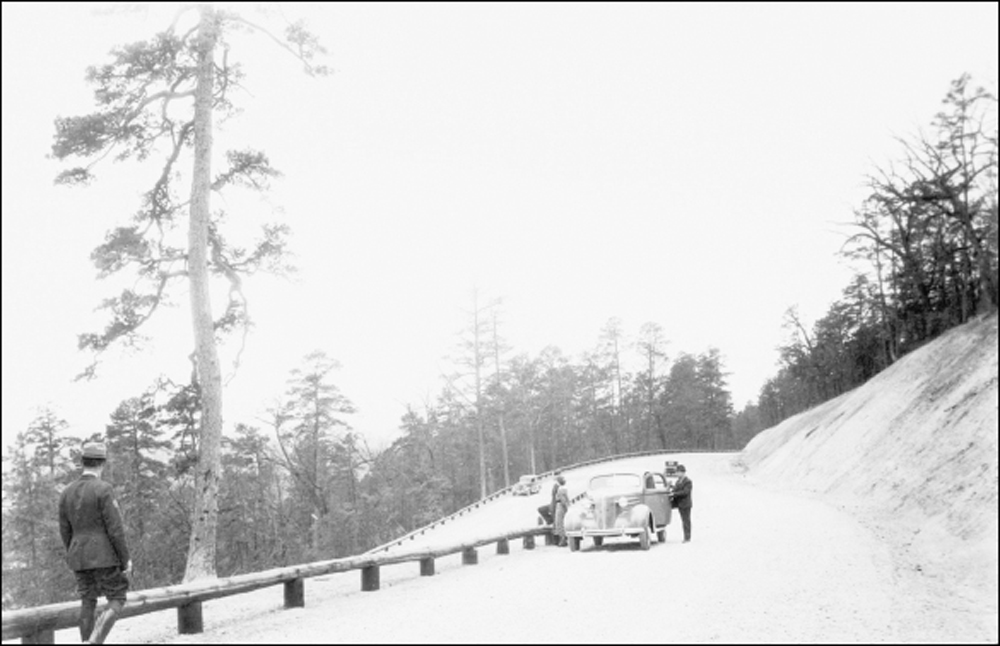

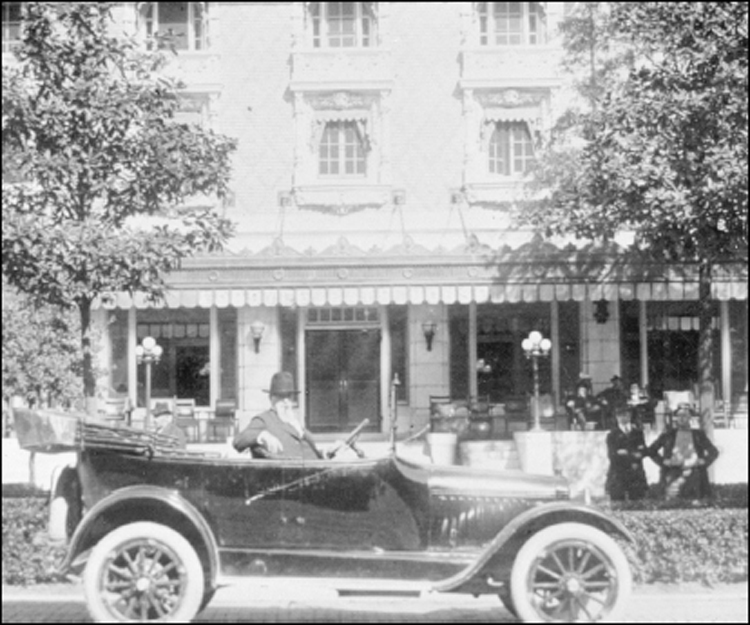

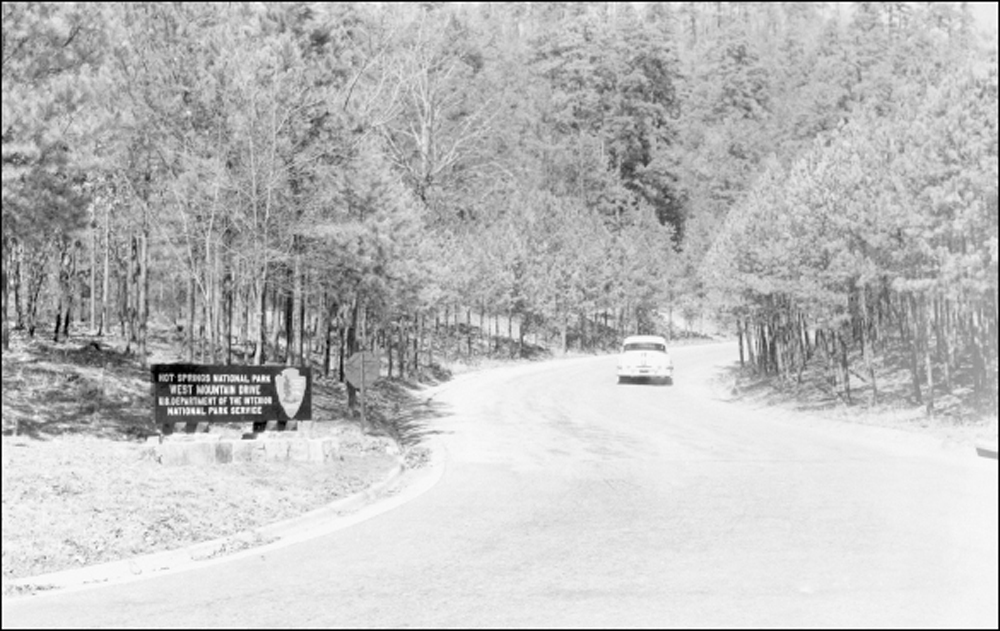

A road to the top of West Mountain had first been proposed by Lt. Robert Stevens in 1894, but it was not completed until 1901. The road was originally restricted to horse-drawn vehicles, but in 1916 the Department of Interior made it the only roadway in the park cleared for automobiles. On February 14, 1920, Gen. John J. Pershing officiated at a ceremony that opened all park roads for automobile travel.

The towers of the Arlington Hotel stand out in a south-facing photograph of Hot Springs. This second version of the hotel was erected on park property in 1893. The Superior, Hale, and the white square structure of the Maurice Bathhouse are visible beyond the hotel. (Photograph by H.D. Miser, courtesy of the US Geological Survey.)

At the summit of Hot Springs Mountain, an 80-foot wooden tower was built in 1877 to provide panoramic vistas to anyone who made the ascent. After it was struck by lightning and burned down, a steel tower was put in its place by the Texas Steel Bridge Company in 1906. Equipped with stairs and an elevator, the 185-foot tower was a huge success. Access to the tower cost 25¢ for each adult.

This aerial photograph of Hot Springs Mountain, taken from an overlook on West Mountain Drive, shows the extent of the hiking trails and roads over the hillside. In the lower-right corner, the dome of the Quapaw is visible above the trees; the two square buildings with three windows are the cooling towers for the bathhouses.

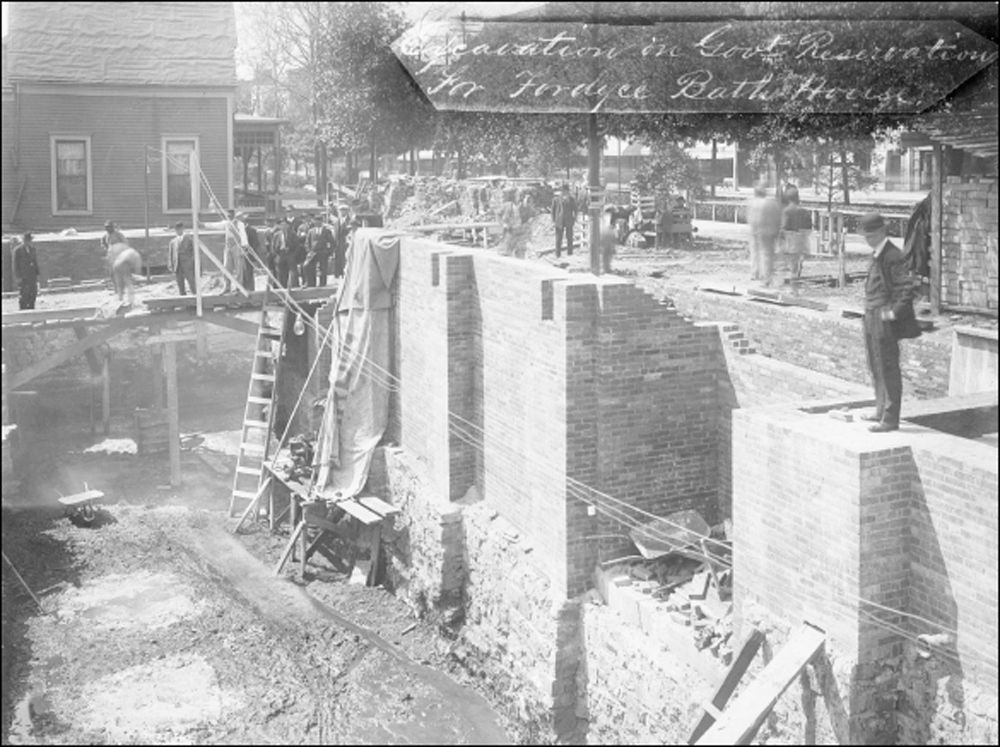

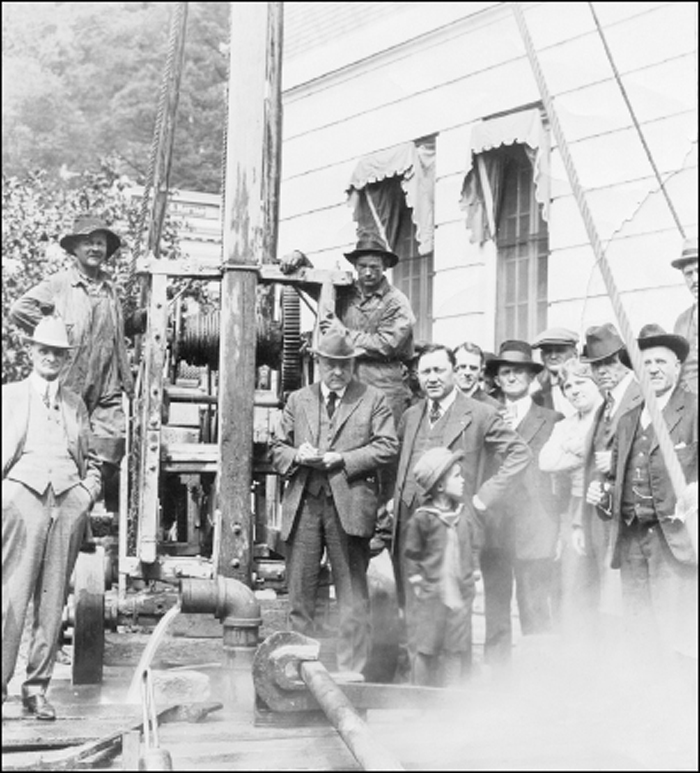

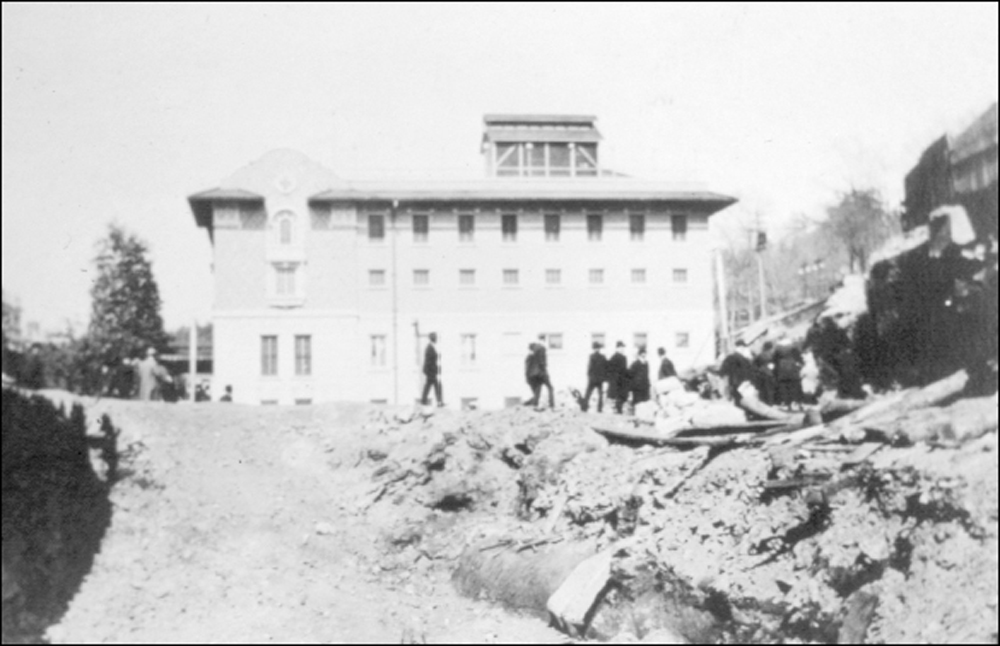

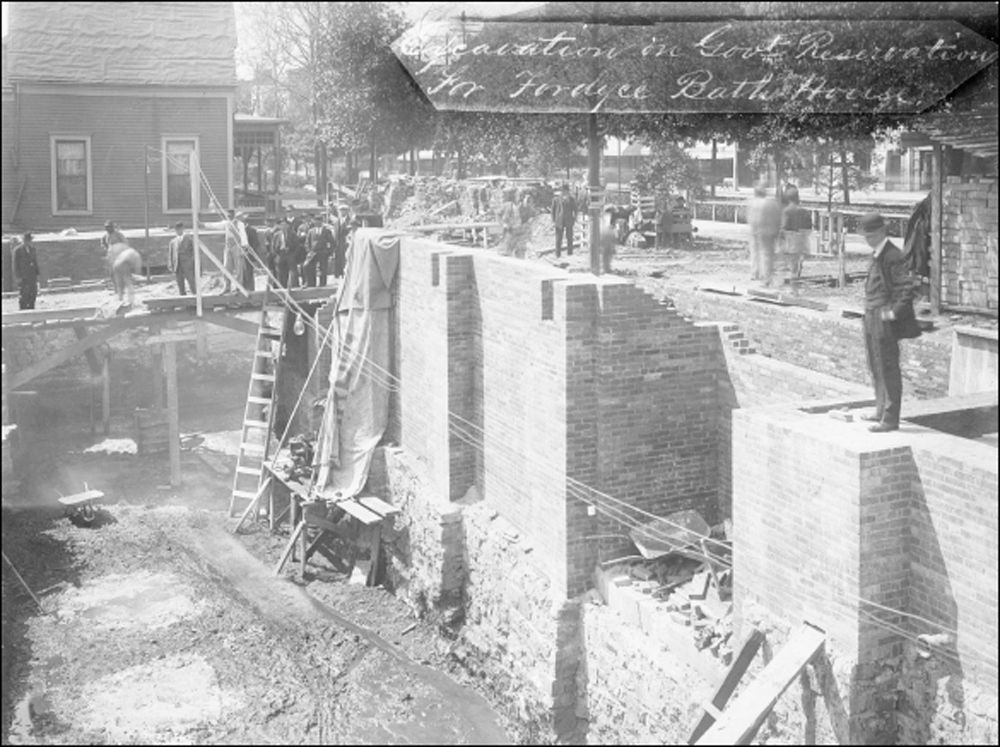

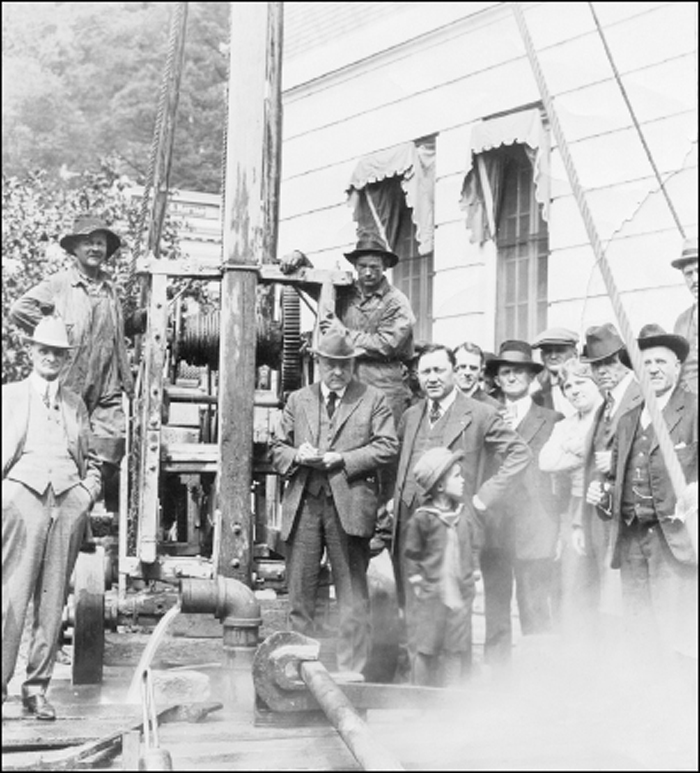

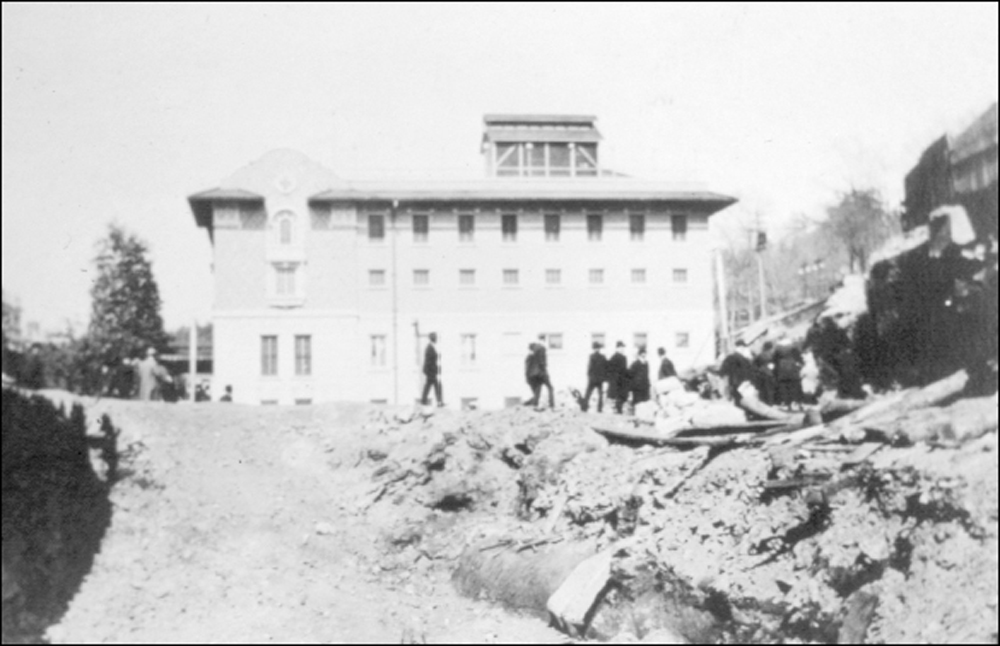

With the Palace Bathhouse closing in 1914, the site was readied for the next generation of bathhouse. An initial job to be completed was the excavation and construction of new basement walls and a water reservoir (above). The side of the wooden Horseshoe Bathhouse is visible in the upper left. Built at a cost of $200,000, the new structure, called the Fordyce Bathhouse, would need a dependable flow of thermal water. Drilling a new well on the south side of the Fordyce (at right) are John Fordyce, in the center with clipboard in hand, and Jack Manier, manager of the new bathhouse, to the right of Fordyce.

Samuel Fordyce poses in front of his new bathhouse. A businessman from St. Louis, Fordyce initially came to town seeking relief for his health problems in 1873. He became enamored of the healing abilities of the waters. He moved his family to the city in 1876. Fordyce’s investments not only included his magnificent bathhouse, but the city opera house, municipal utility systems, hotels, a country club, and the city streetcar system.

The Fordyce was designed to be one of the most opulent buildings on Bathhouse Row, and its construction drew wide interest from not only future patrons, but other bathhouse owners as well. Building on the site of the former Palace Bathhouse, Samuel Fordyce raised the quality of the bathing experience, with stained-glass windows, imported marble bathing enclosures, and innovative Zander physical-therapy equipment.

A music room on the third floor of the Fordyce Bathhouse gave ladies and gentlemen a place to relax, visit with friends, or write letters before or after their baths. From the stained-glass ceiling to the elegantly tiled floor, patrons knew they were in the best facility. A screen at the end of the room closes off the ladies’ private parlor; men had their own at the opposite end.

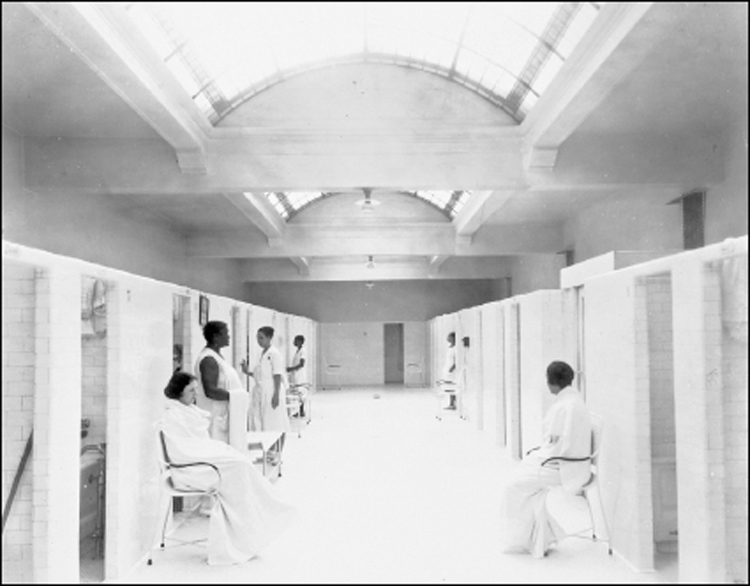

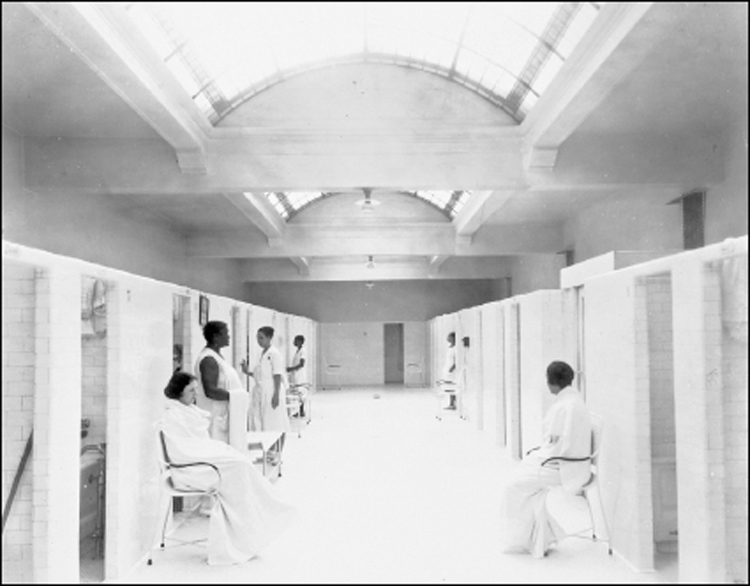

Once inside a bathhouse, patrons would be guided by attendants through their thermal bathing regimen. The ladies bath hall in the Quapaw was filled with diffused illumination from the overhead skylights, and the individual stalls were tiled to provide a hygienic environment. The relaxing atmosphere left visitors feeling rejuvenated and renewed.

The 1932 National Park Service Superintendents’ Conference was held at Hot Springs National Park, with much of the discussion centered on master planning for parks. In this official conference photograph, Supt. Thomas J. Allen is fourth from the right in the front row, and Director Horace is fifth from the right in the front row. This photograph was taken in front of the Superintendent’s Office building at the south end of Bathhouse Row.

Named after Army lieutenant Robert R. Stevens, the Hot Springs Reservation improvements officer, Stevens Balustrade, was designed to present a formal entrance to the park, with an enclosed shell fountain and stone steps leading to a hillside bandstand. Lit at night with streetlamps, the bandstand provided a place for musicians to serenade strolling tourists.

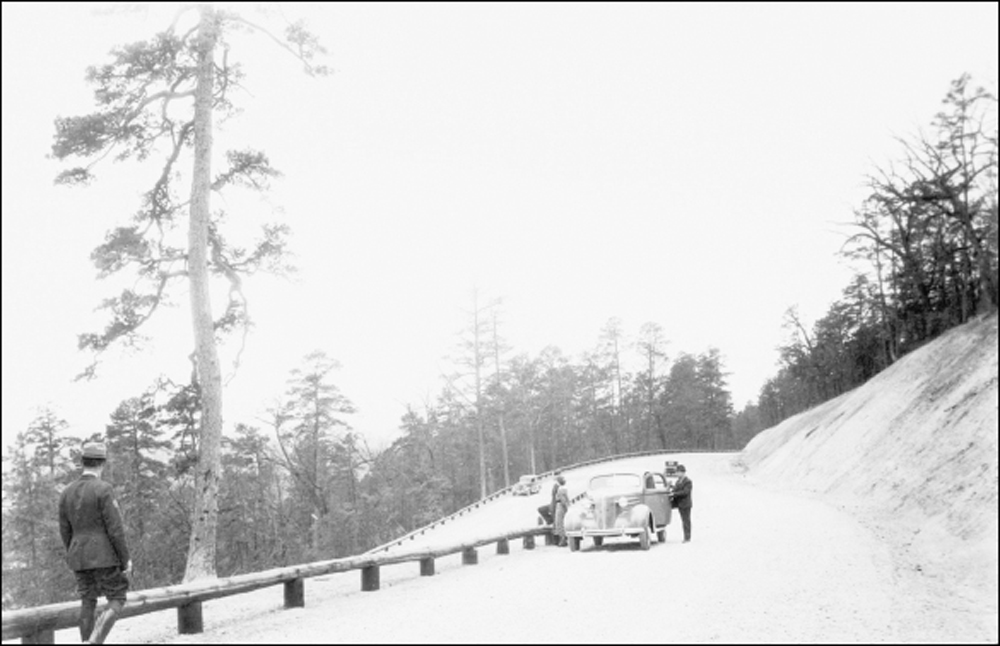

Once West Mountain Drive was carved out of the mountainside, it became a task to keep the packed dirt road usable. Heavy rains would cause soil to slide or slump onto the roadway. Here, park maintenance workers install log cribbing to help retain a slope. The road would be paved by 1937.

In March 1933, the Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) was formed as one of President Roosevelt’s New Deal proposals to combat the economic effects of the Great Depression. The plan was to engage a quarter of a million unemployed men in public works and conservation projects across the country, primarily within national parks and forests. That May, a CCC camp was established near Hot Springs National Park to assist for six months.

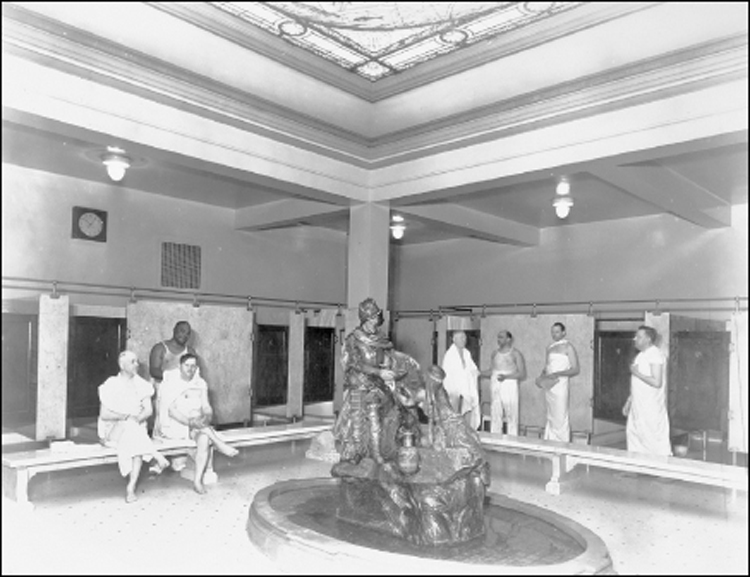

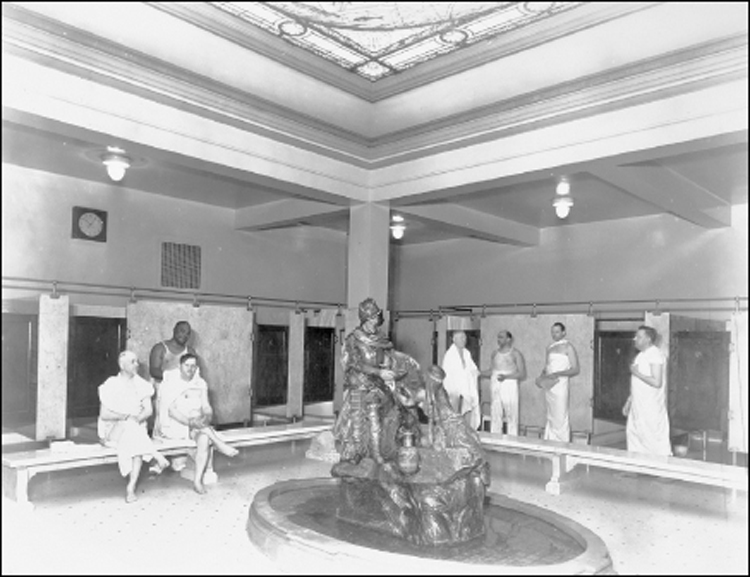

The men’s bath hall in the Fordyce was elegantly furnished with a stained-glass ceiling, marble bath stalls, and a large fountain depicting explorer Hernando de Soto receiving a cup of thermal water from a young Native American woman. The five patrons are being cared for by two African American bath attendants.

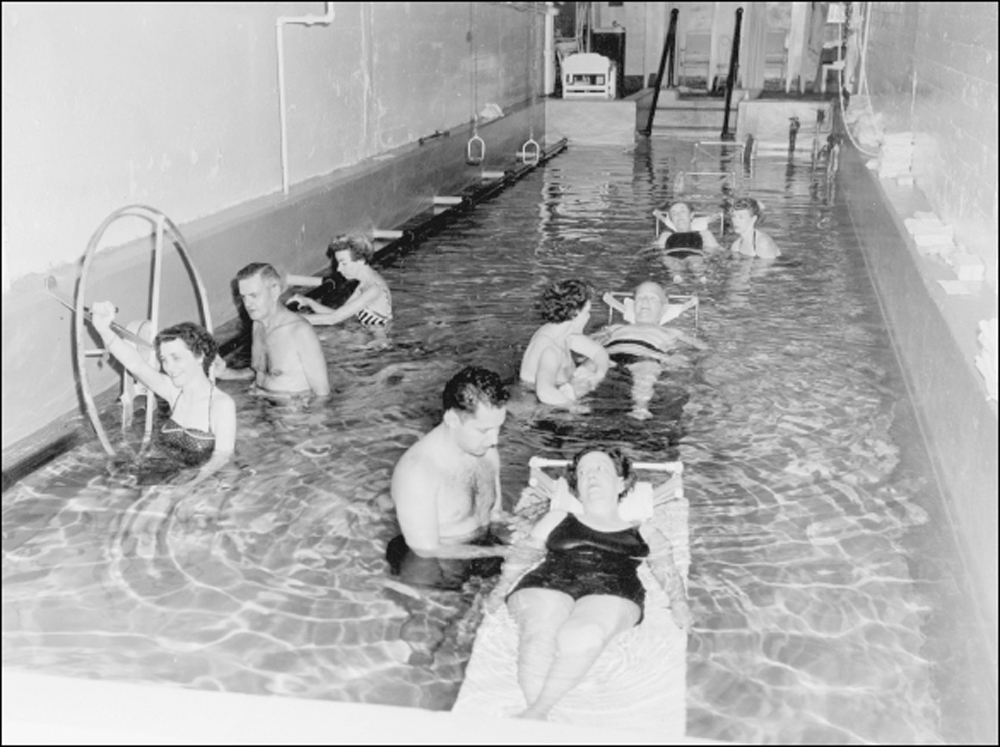

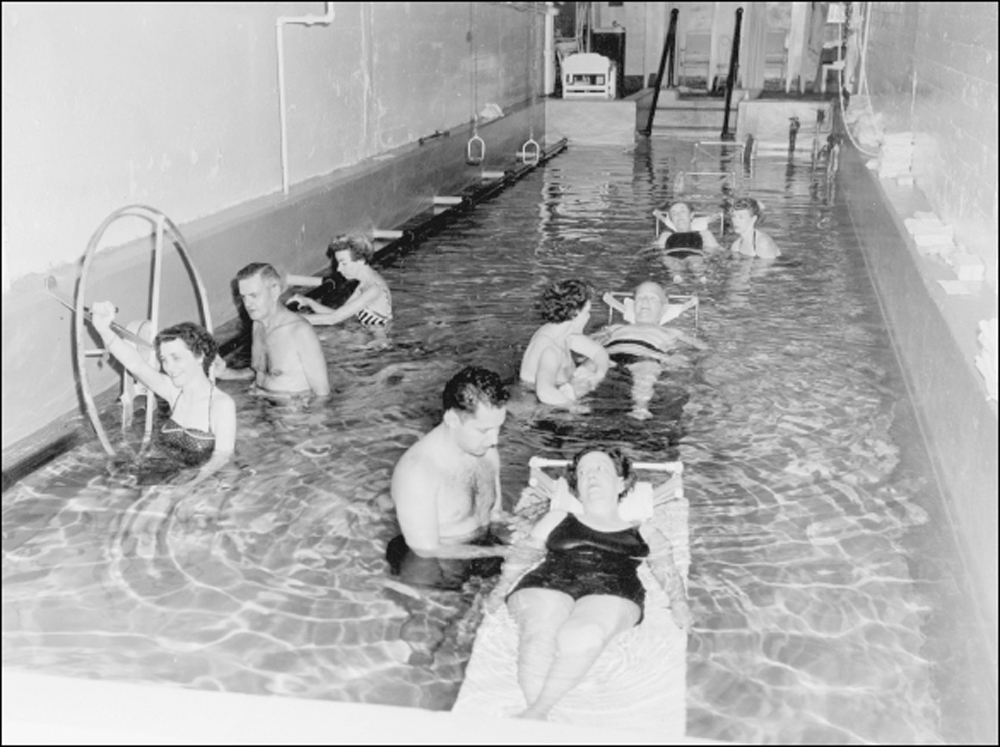

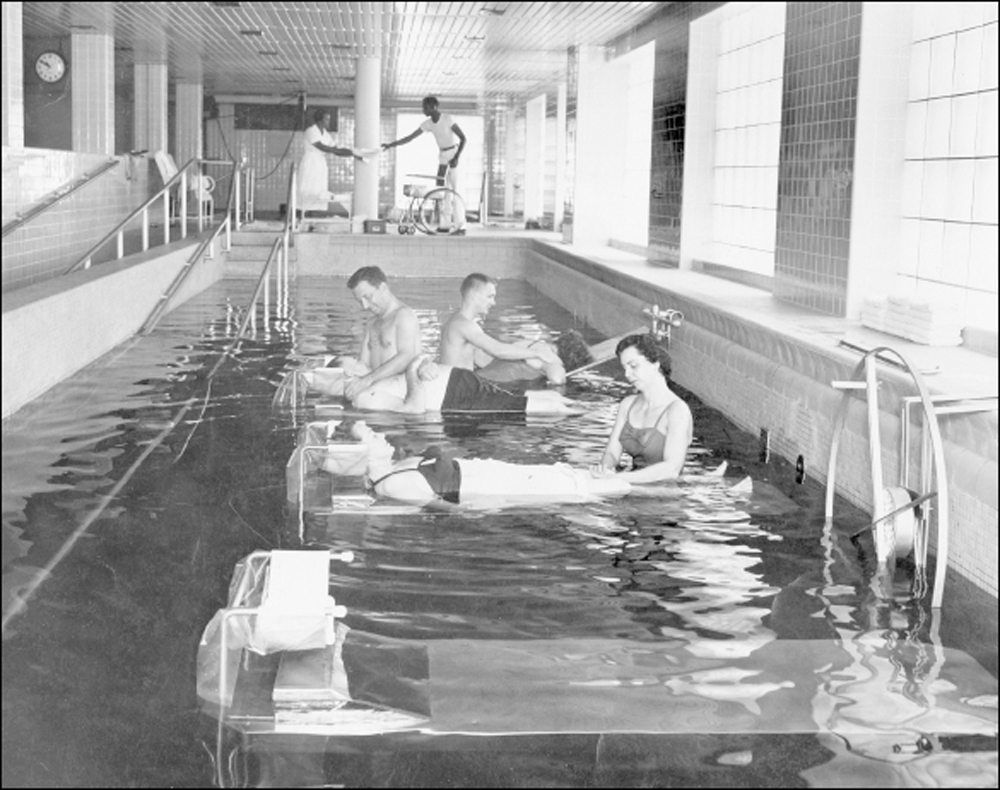

As part of their therapy, patients were taken to the basement of the Maurice to the thermal pool. There, they would be helped by attendants to utilize exercise equipment, seen here along the left side of the pool. Patrons with limited mobility were floated on cots while their limbs were massaged by the therapists.

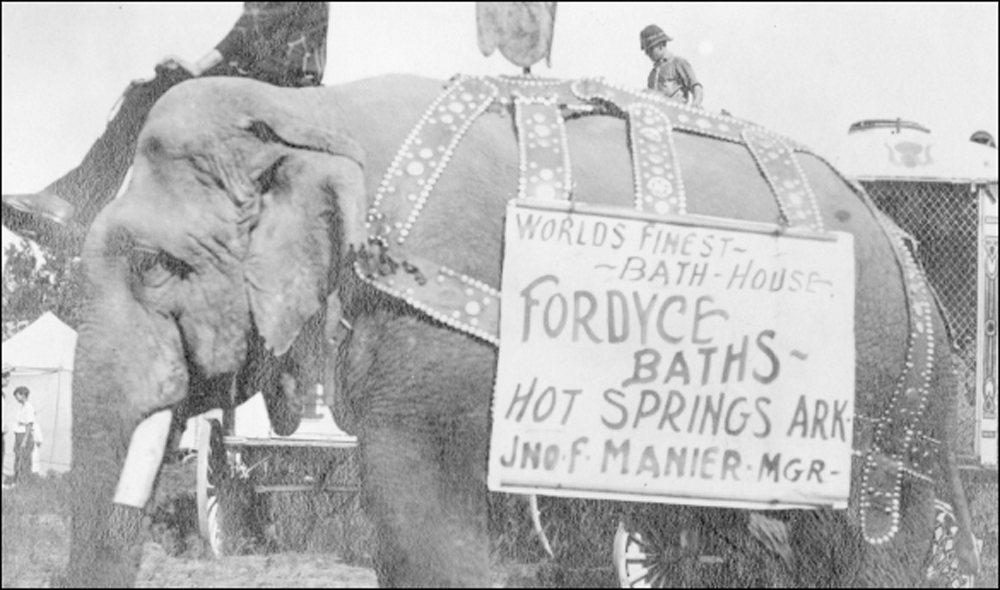

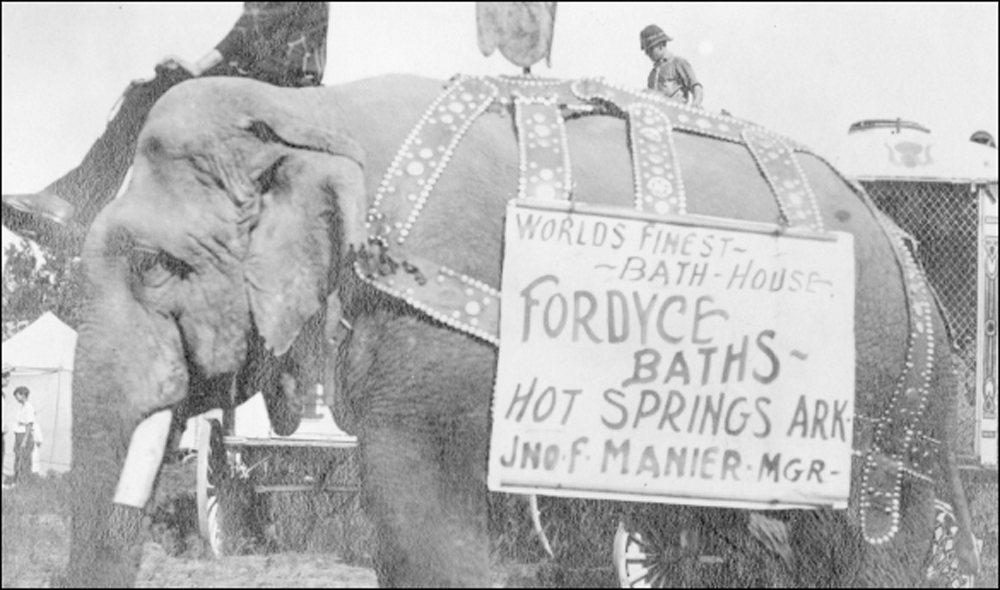

When the Sells Floto Circus visited Little Rock, the manager of the Fordyce, Joseph Manier, found a way to advertise the bathhouse at the state capital. Manier paid $20 to place a large hand-painted sign on the elephant so that everyone who attended the circus would also think about traveling to Hot Springs for a bath.

Built in 1896, the Marine Bandstand Pavilion above the Stevens Balustrade was a venue for concerts and musical interludes for the next 30 years. A pathway at the back of the bandstand allowed patients from the Army and Navy General Hospital, located just behind the bathhouses, to access the area by the carriage road.

As its notoriety grew, Hot Springs National Park became a welcome stop for many athletes. Famed boxer Jack Dempsey (second from left) strolls the park trails with two unidentified men and his movie-star wife, Estelle Taylor. Dempsey was there to meet with boxing promoter Tex Rickard, who was in town taking the baths. It was during this visit that the bout with Gene Tunney was planned. (Courtesy of Garland County Historical Society.)

Hattie Caraway of Arkansas was the first woman elected to the US Senate, the first woman to preside over the Senate, and the first woman to chair a Senate committee. Serving from 1932 to 1945, she supported Pres. Franklin D. Roosevelt’s economic recovery legislation during the Depression. She and the rest of the Arkansas congressional delegation accompanied Roosevelt when he visited Hot Springs National Park in 1936.

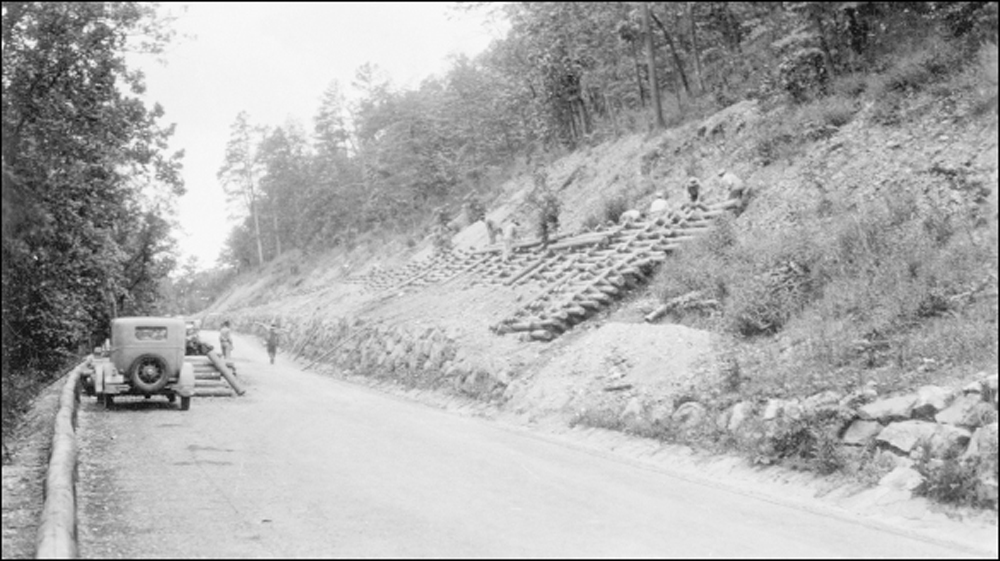

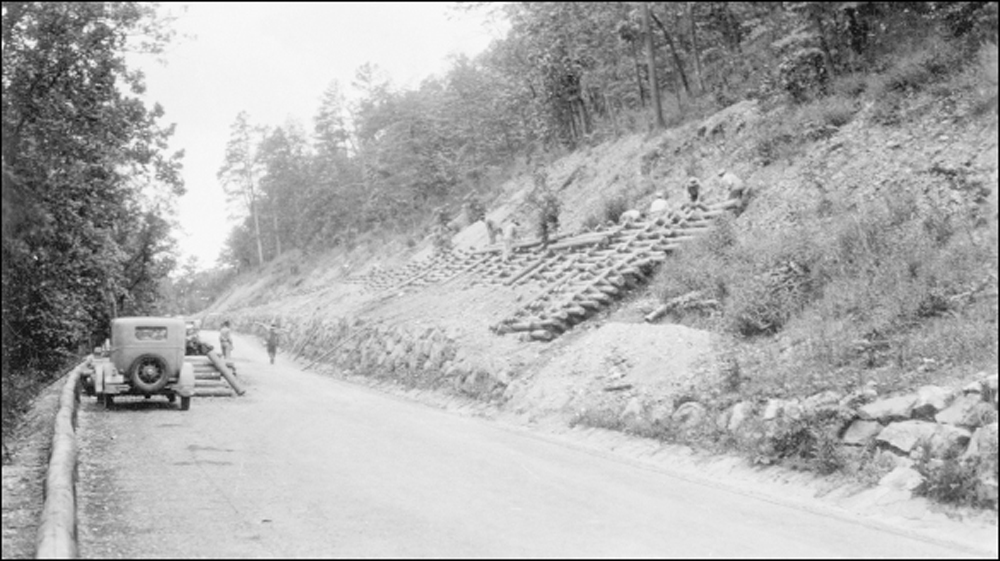

Erosion of the precipitous slopes along West Mountain was often a problem during heavy rains. Stone retaining walls were installed on the south-facing slope in 1914 in an effort to put an end to these slumping issues. Above, unidentified park maintenance workers stand proudly with their completed stair-step retaining walls. The photograph below is of the same location along the road in 1925. The stone walls are still standing and have become part of the overall terrain of the hillside. Automobiles, horses, and pedestrians often shared the road to partake of the natural wonders of the park.

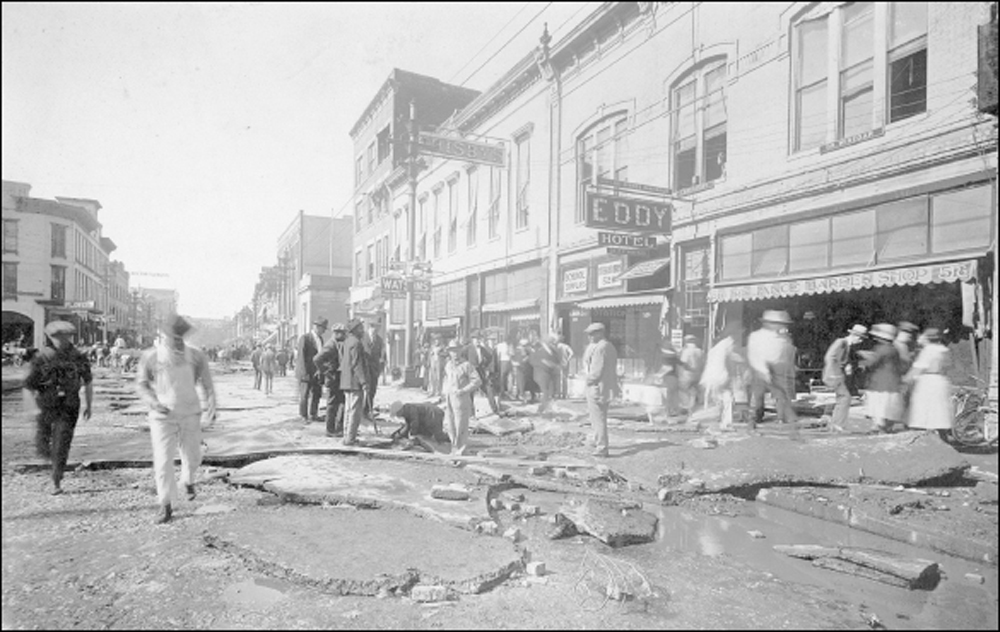

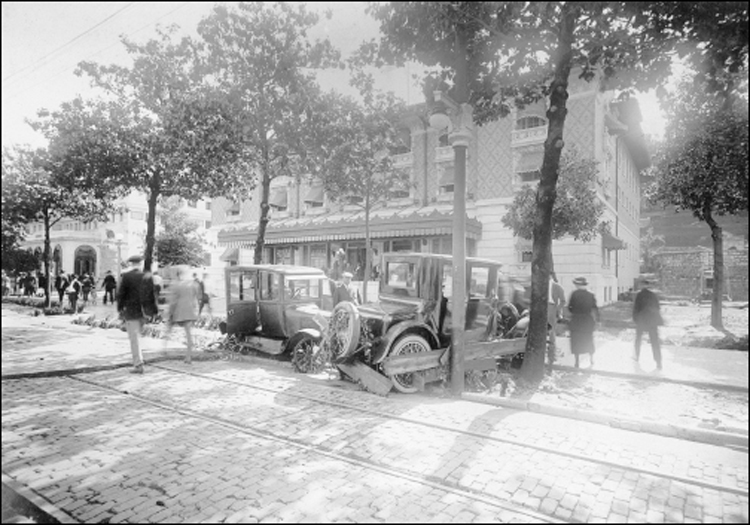

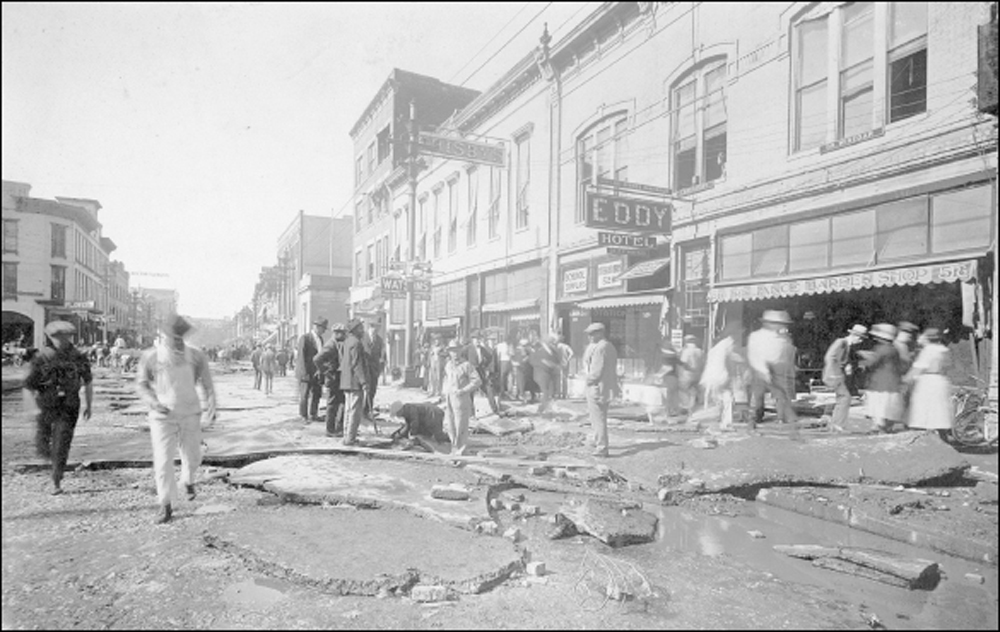

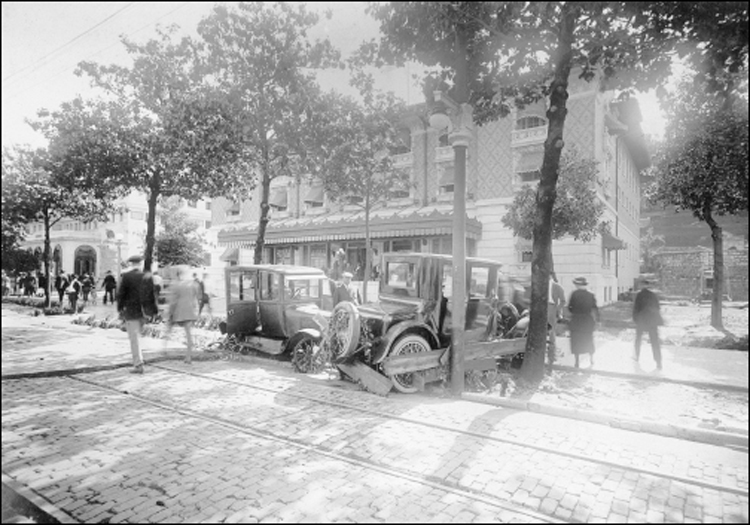

On May 14, 1923, a catastrophic flood left Central Avenue with nine feet of water rushing through it. During the event, four feet of water rose on Bathhouse Row, but the businesses were still able to open to patrons. Once the floodwaters receded, the people of Hot Springs began the arduous task of cleaning up the debris on Central Avenue. The photograph above shows the street pavement in front of the Lamar Bathhouse broken into large slabs. The image below depicts two cars that were washed away during the flood and wedged into the trees in front of the Fordyce Bathhouse. In the foreground, the old brick street and trolley tracks are visible since the covering pavement was washed away during the deluge. This would not be the last flood to threaten the city. (Author’s collection.)

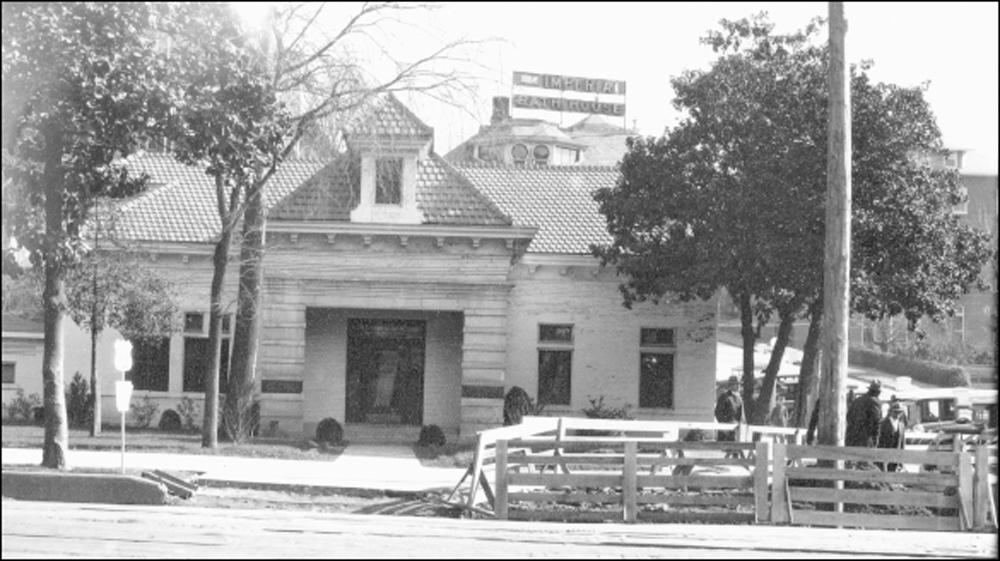

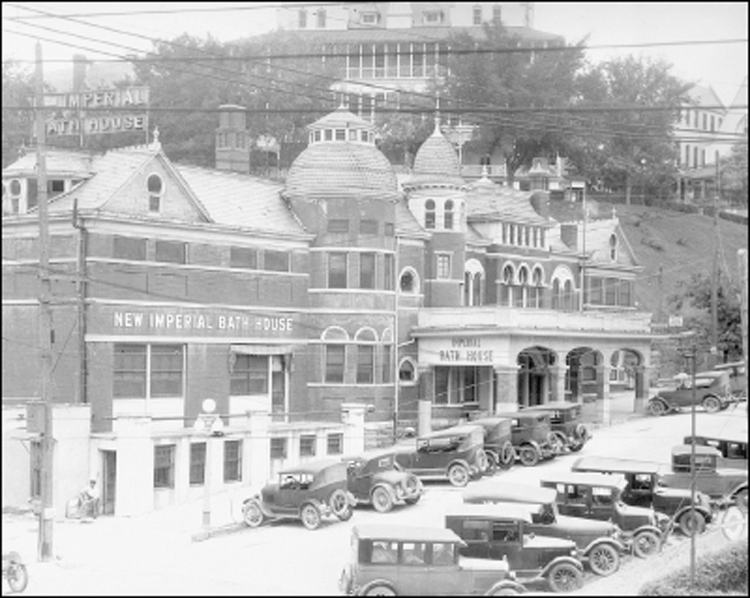

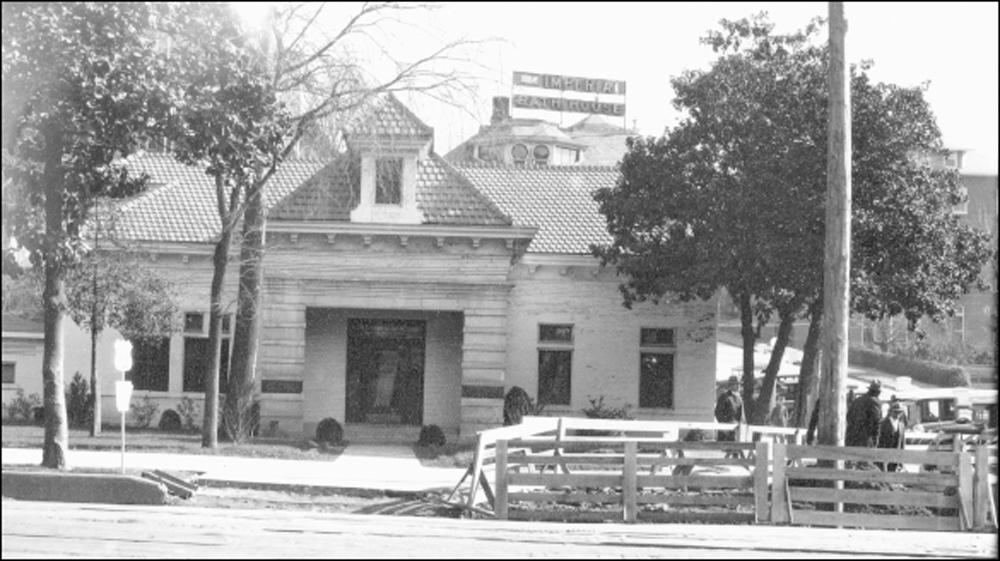

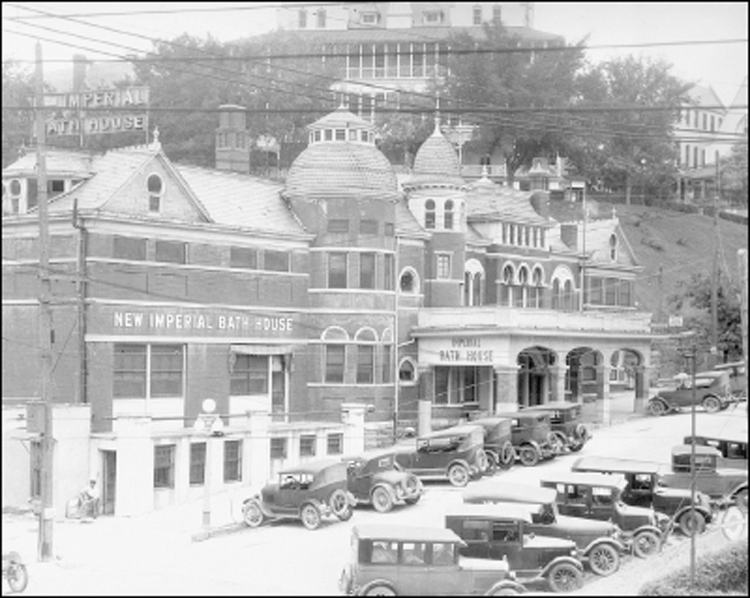

As the Superintendent’s Office began to show its age, plans were discussed to remove the building and replace it with a new facility. New sidewalk plantings and the installation of the Noble Fountain had made the corner a natural gathering place for visitors. A sign for the new Imperial Bathhouse is visible above the roof of the Superintendent’s Office.

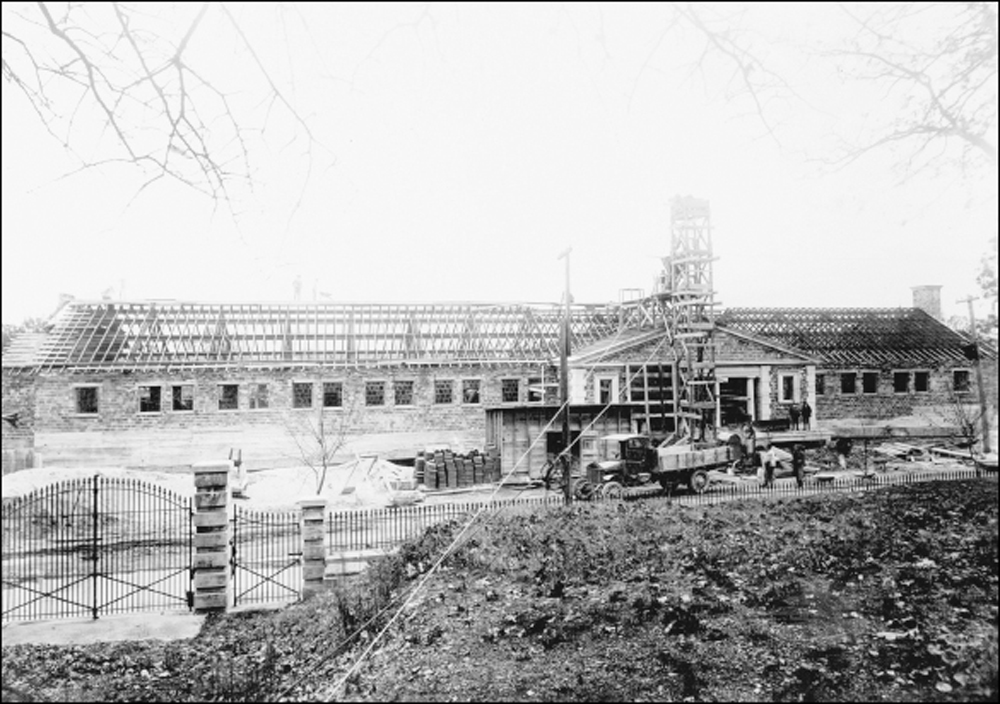

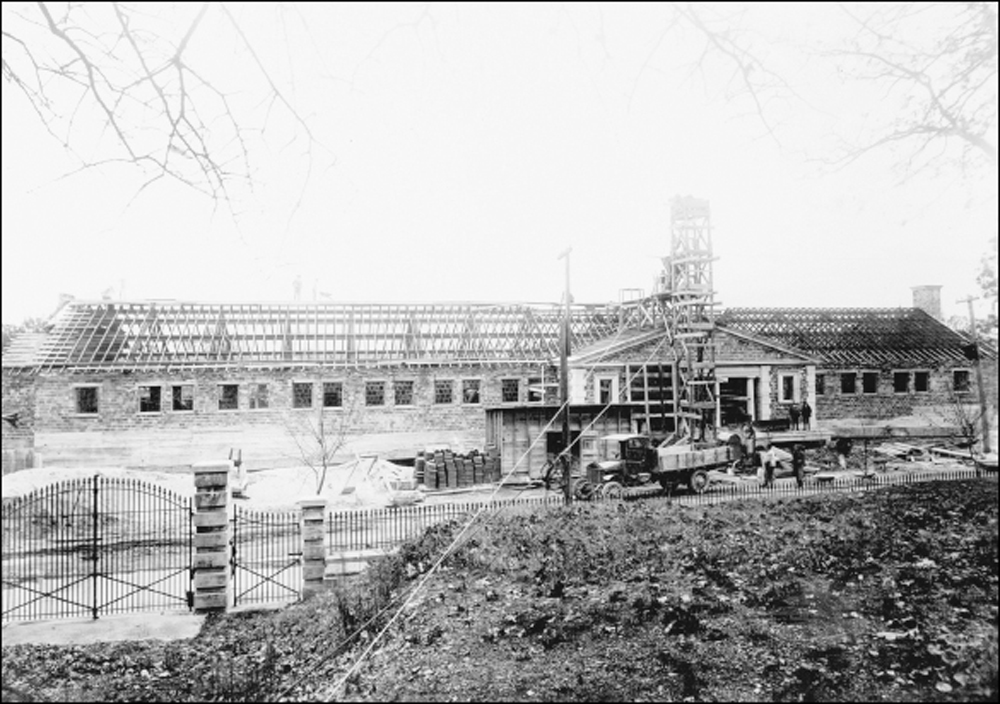

In 1936, construction began on Public Works Administration (PWA) Project No. 534, and the new park Administration Building began to take shape. This building would house not only administration functions, but also contain a visitor center and museum. These new amenities for guests would remain in this building until the renovation of the Fordyce Bathhouse into the park Visitor Center and Museum in 1989.

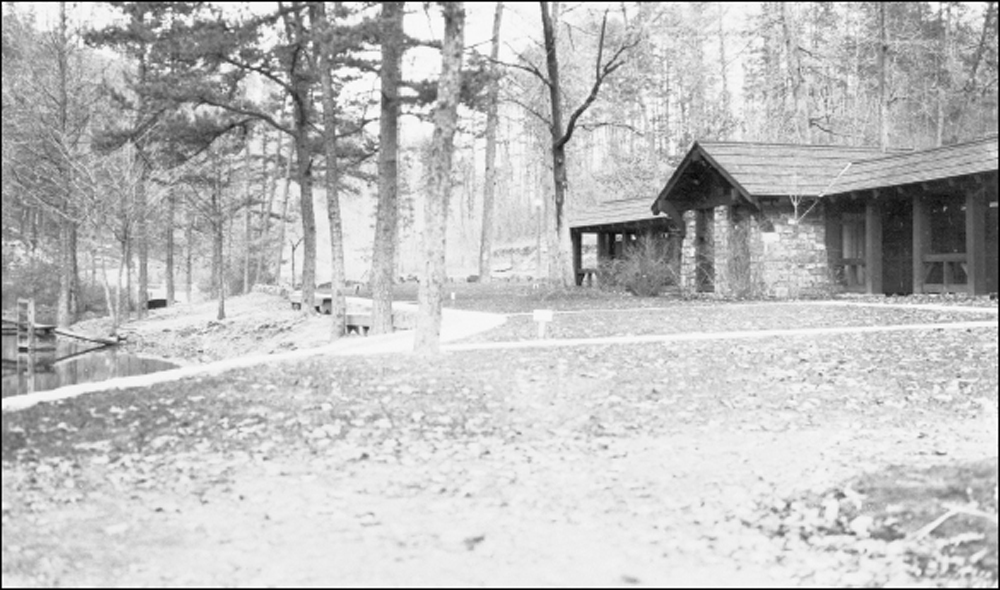

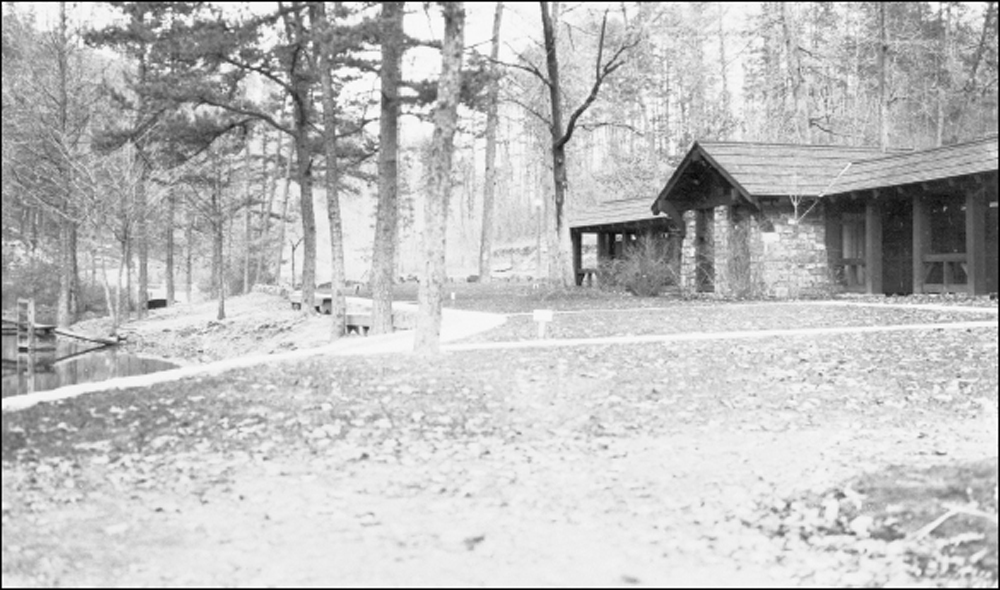

Located two miles northeast of Bathhouse Row, the park’s only campground has long been a popular destination for visitors wishing to commune with nature. The property was donated to the park by John Fordyce through the Hot Springs Chamber of Commerce in late 1924. It had originally been a camping area located on the Fordyce estate. A new entrance was added with stone pillars to attract visitors to the campsite.

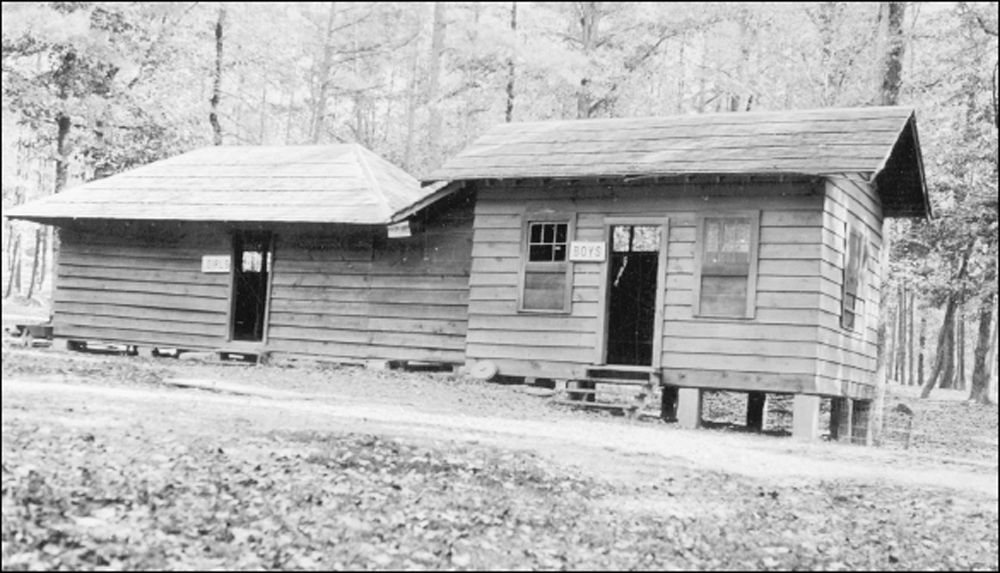

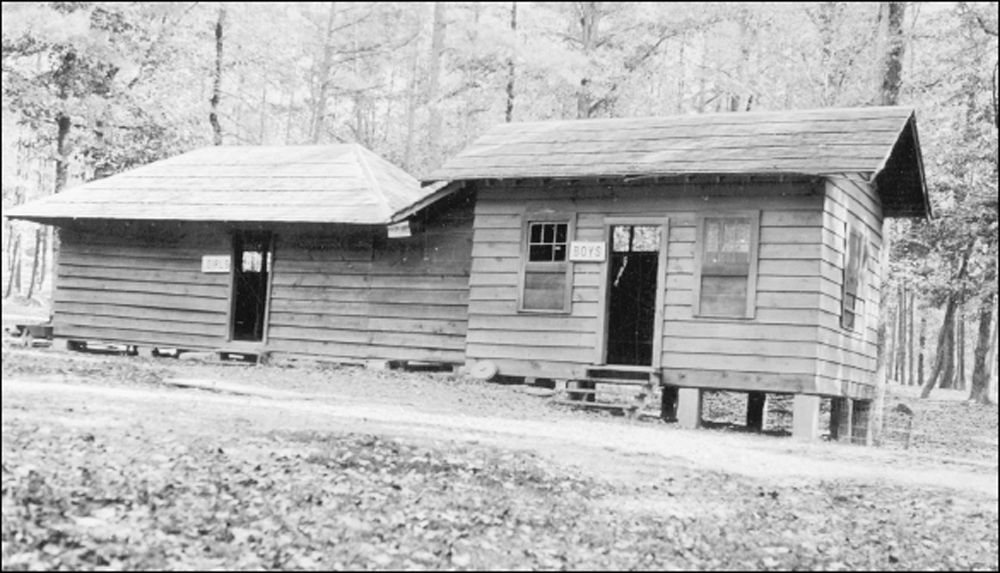

An early photograph of the changing stations at Gulpha Gorge shows the rustic buildings for both boys and girls. During the intense summers, the swimming pool was the best place to cool off. The area was formally named Gulpha Gorge Campground in 1939 by Supt. Preston Patraw so that the campground would have a “distinctive” name like other places within the National Park System.

A swimming pool already existed at the automobile tourist camp in Gulpha Gorge when it was donated to the park in 1924, but park workers immediately deepened and cleaned it. In 1933, the entire campground was upgraded by CCC workers, who excavated the swimming pool to make it larger. It was a popular spot in the heat of summer, attracting locals and park visitors alike.

As Americans began to take more leisure time after World War II, the campground and picnic area in Gulpha Gorge Campground became a destination for visitors from out of town. New campsites were laid out to accommodate the growing trend of families heading to the National Parks with a camping trailer for recreation.

First authorized by Congress in 1892, plans for the Whittington Avenue Lake Reserve were not finalized until early 1896. Work on the site began later that year, and the project was completed in 1897. The finished park originally featured two boating lakes with observation pavilions, five bridges over Whittington Creek, a music pavilion, carriage drives, and this tennis court with two spectator pavilions.

This photograph from the spring of 1934 shows construction progress on the new park maintenance and utility complex on Whittington Avenue. The tennis court and spectator pavilions at the west end of Whittington Park are visible in the background. The new maintenance complex, built with WPA funding, was completed in 1936.

Many popular entertainers visited the Hot Springs area for a chance to relax, including radio singer Kate Smith. Unfortunately, during Smith’s stay at the Mountain Valley Hotel in 1934, the facility caught fire and burned to the ground. Although uninjured, she lost everything, including her luggage. The undaunted Smith was able to supplement her remaining wardrobe with a bath towel from the park.

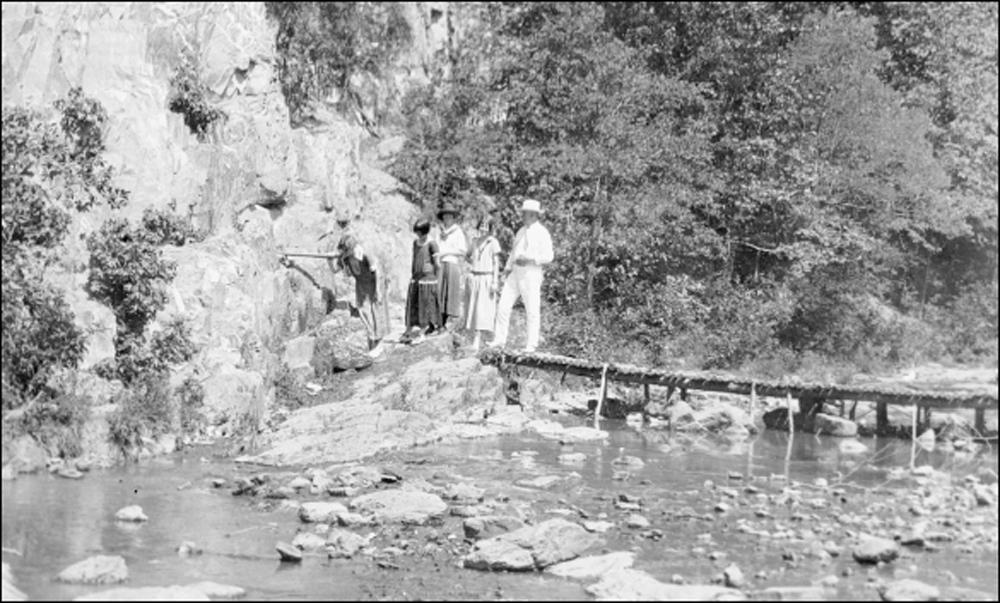

International personalities often made their way to Hot Springs. Opera soprano Lily Pons made a trip to the park and visited the display springs. The French-born singer was the principal soprano at the Metropolitan Opera in New York from 1931 until 1960, and she starred in three films, including That Girl from Paris, which was mentioned by Harry Truman in a letter home during his sojourn in the park in 1937.

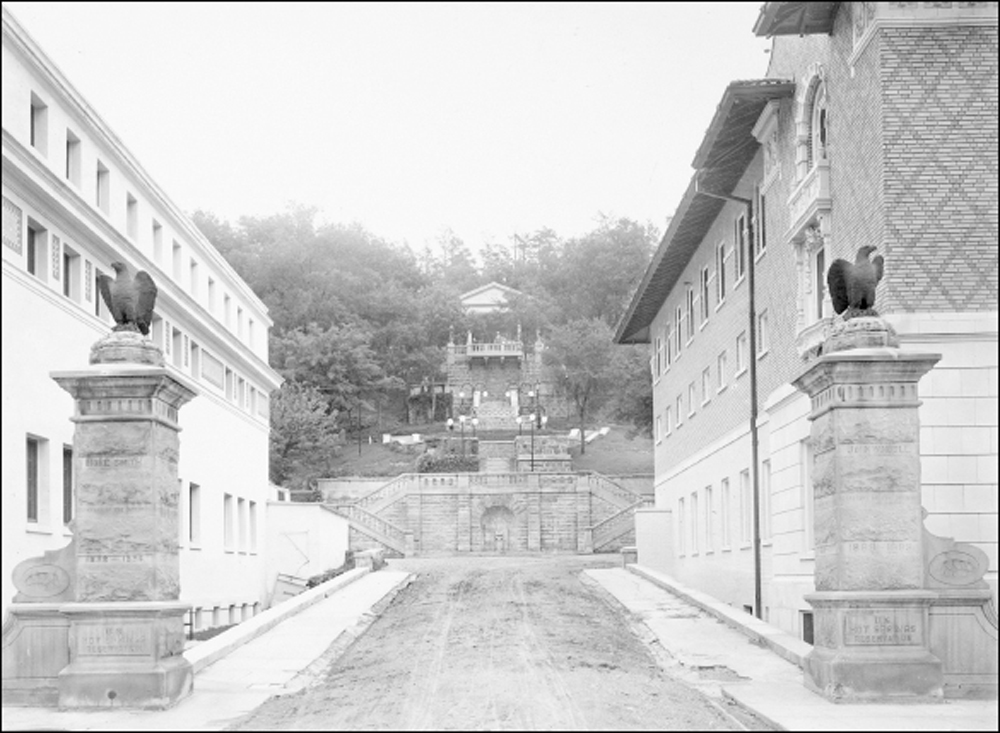

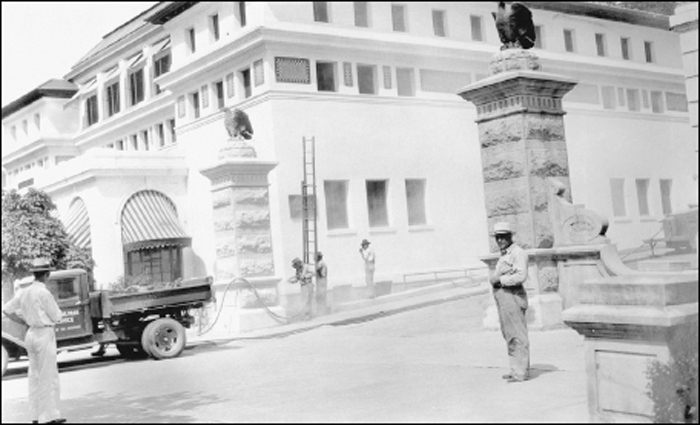

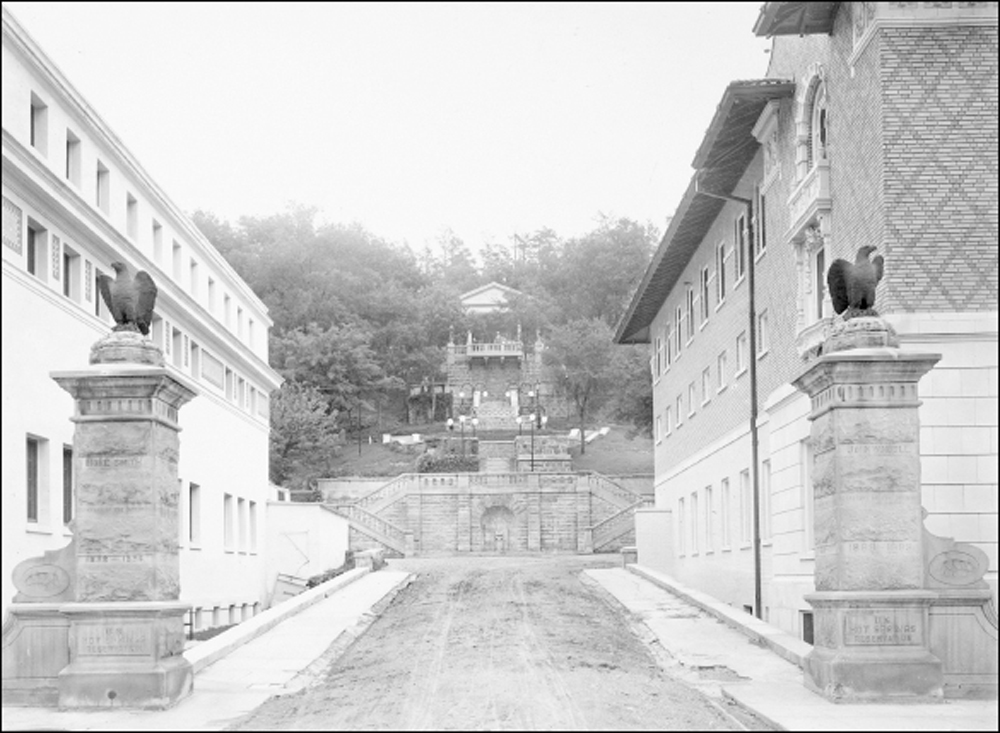

When Lt. Robert Stevens was selected by Secretary of the Interior John Noble in 1892 as the reservation improvements officer for Hot Springs, he immediately contacted the firm of noted landscape architect Frederick Law Olmsted. After a frustrating and brief collaboration, during which few actual plans were created, that relationship was terminated. Stevens selected other designers. One of the few Olmsted design elements to be used was the decorative stone columns that flank the formal entrance. Completed in 1893, the columns feature large bronze eagles by sculptor Edward Kemeys. The photograph above shows the formal entrance columns, Stevens Balustrade, and the bandstand between the Maurice and Fordyce prior to the paving of the carriageway between the buildings in the 1920s. Below, park maintenance personnel sandblast the columns to clean them in the 1930s.

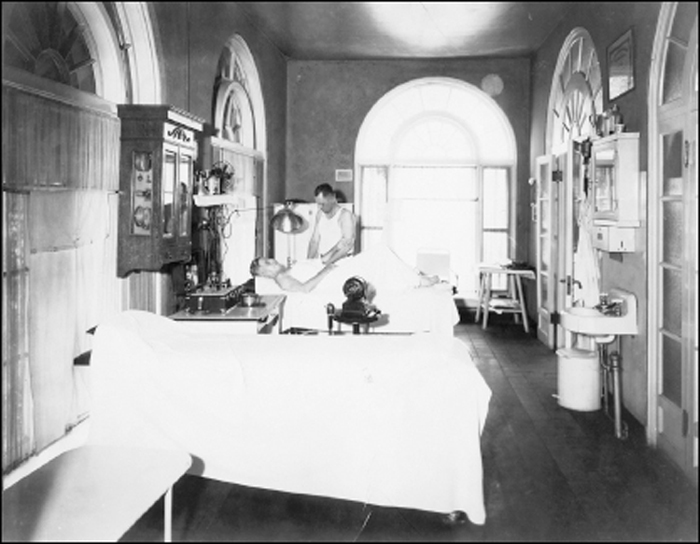

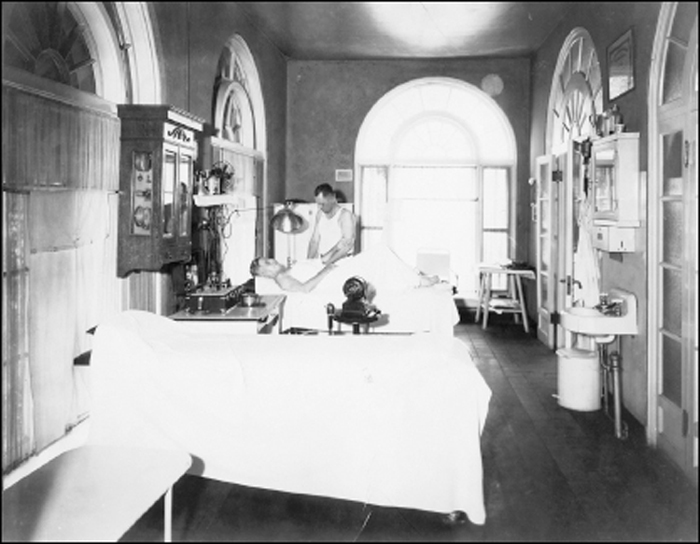

As part of their bathing amenities, many bathhouses offered patrons the services of professional masseurs and therapists. In the early 1920s, the Men’s Massage Room at the Quapaw Bathhouse was equipped with state-of-the-art electromechanical therapy machines, like that in the cabinet on wall to the left, and the small electrical generator on the table.

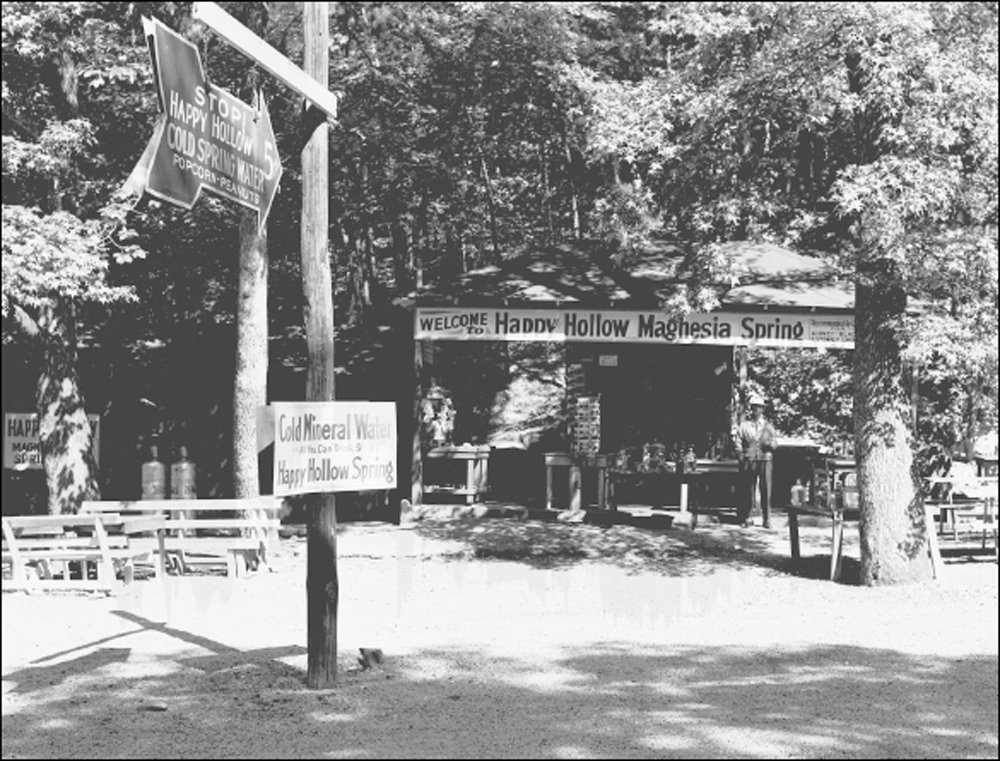

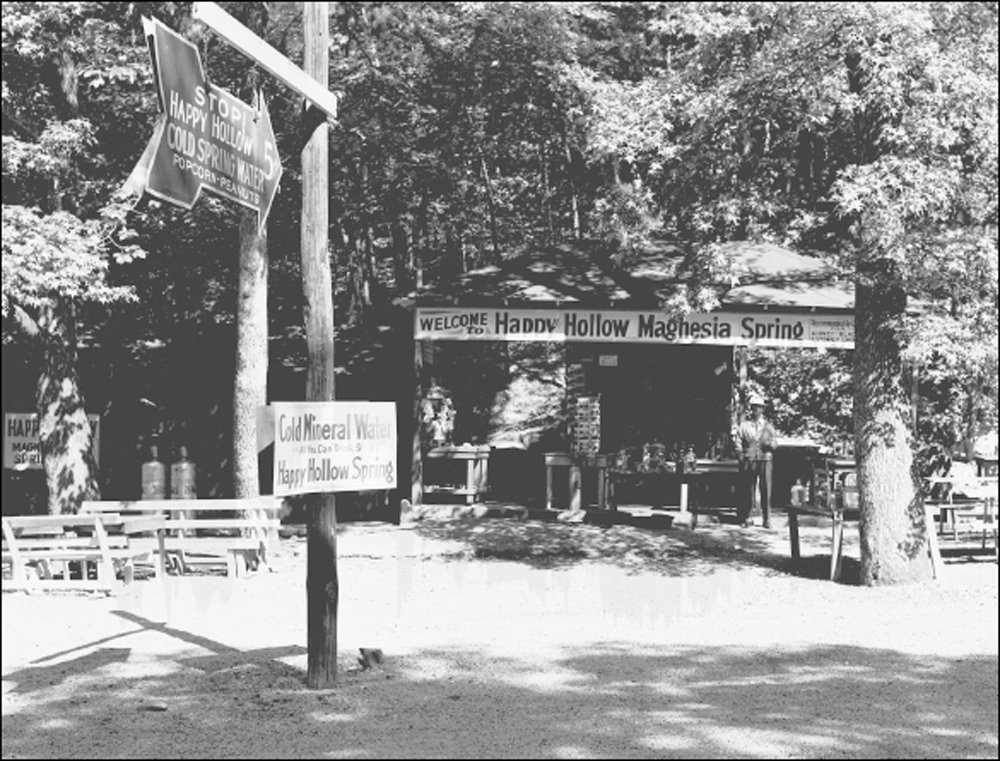

The Magnesia Spring in Happy Hollow on Fountain Street became part of Hot Springs National Park in November 1959, when Supt. Raymond Gregg exchanged parkland behind the Arlington Hotel to the Arlington Hotel Company for the nonfederal inholding surrounding Happy Hollow Spring. A new jug fountain plaza to replace the old facility was immediately begun, and the refurbished Happy Hollow Spring was officially opened on April 1, 1960.

Hot Springs National Park ranger James Alexander Cary was the first National Park Service ranger to be murdered in the line of duty. Ranger Cary had been with the park service since 1923 and previously served in the US Navy aboard the USS Orient in World War I. Cary was to testify in a court case against bootleggers operating in the park, but before the trial was held, he was ambushed and shot while patrolling West Mountain on March 12, 1927. When he failed to return home in the evening, he was reported missing, and a search began on West Mountain at the site of Cary’s empty patrol car. His body was not located until the next day. It was found on the mountainside by several members of his family. A lengthy investigation involving an undercover FBI agent culminated in the arrest of five local men. Although these suspects went on trial for Cary’s murder, no one was ever convicted of the crime. (Courtesy of James O. Cary.)

For years, Iron Spring in Gulpha Gorge Campground had been popular with visitors for its cool, refreshing water. It had no connection with the thermal springs on the opposite side of Hot Springs Mountain. In 1957, it tested positive for contamination and was closed. The water was diverted into Gulpha Creek.

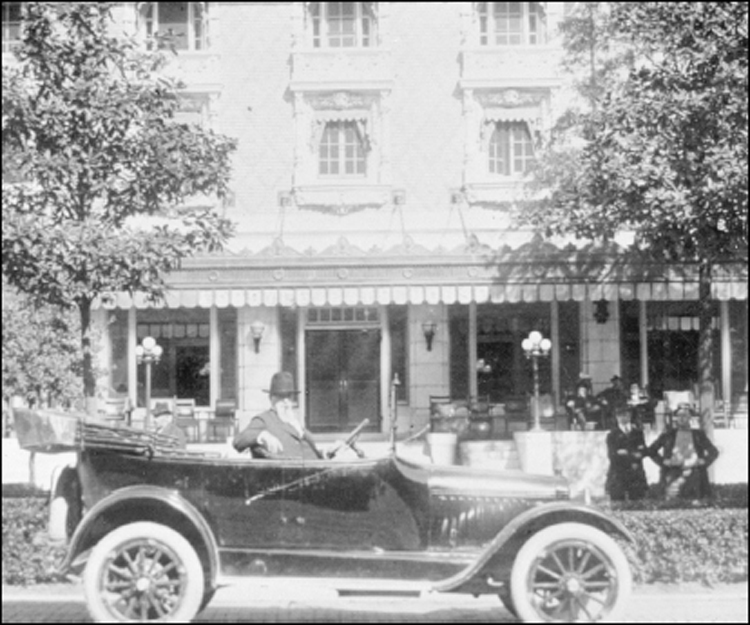

Long a proponent of thermal hydrotherapy, Pres. Franklin Roosevelt visited the park in 1936 during the Arkansas centennial celebration. Riding in the jump seat in front of the president is former park superintendent Thomas Allen, recalled from his new post at Rocky Mountain National Park specifically for the president’s visit. After an inspection of the bathhouses, Allen accompanied the presidential party on a drive over the new West Mountain road.

Completed in 1893, the Imperial anchored the south end of the reservation on the former site of the Huffman-Hamilton Bathhouse. The imposing brick structure was the most elaborate bathhouse until the construction of the new Fordyce in 1915. Offering individual dressing rooms and a gymnasium, it was a step above the wooden bathhouses. The Imperial was torn down in 1937 to make way for the southern entrance of the Grand Promenade.

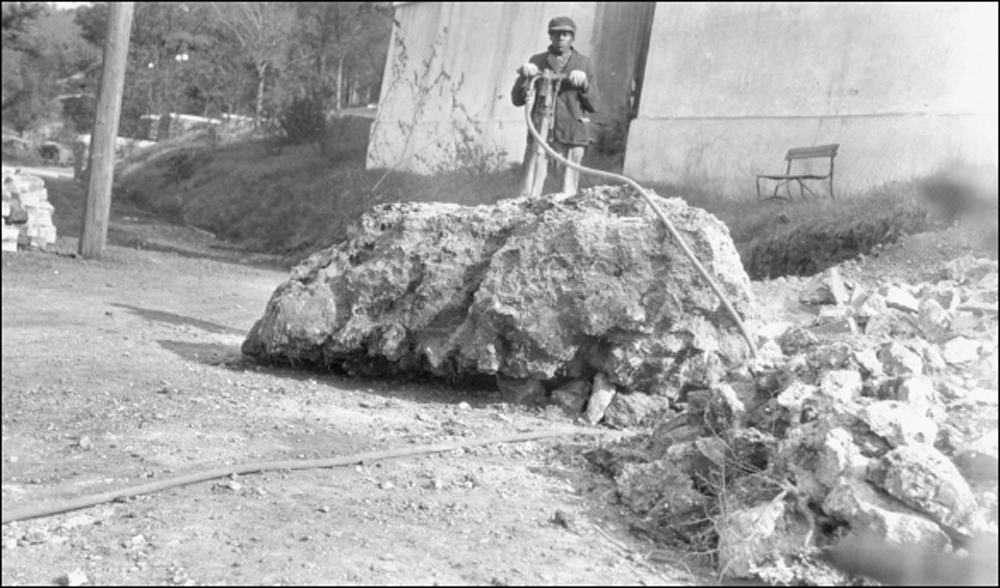

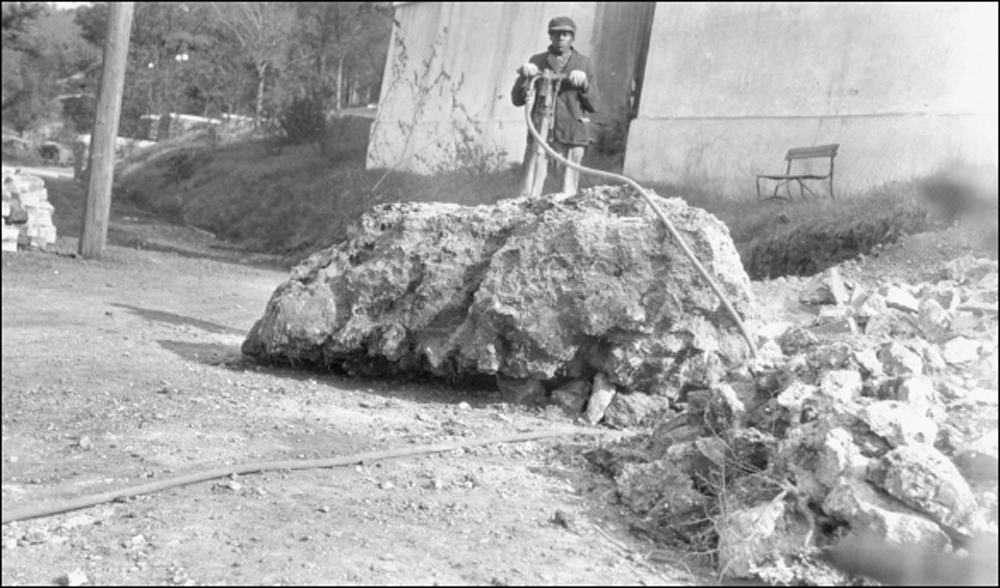

Grading and excavating for construction of the Grand Promenade began in 1933. Here, a worker breaks up a large tufa dome with a jackhammer. This wide walking path was designed to traverse the hillside just behind Bathhouse Row, from Reserve Street to Fountain Street. It would not be completed as originally planned until 1958. It was made a National Recreational Trail on April 14, 1982.

With the help of public works funds, Gulpha Gorge Campground was updated to handle the large crowds with a new sewage system, a changing building, and renovations to the swimming area. By the 1940s, the swimming pool had become contaminated and was closed by the Public Health Service. Park maintenance workers removed the dam, allowing the water to drain into the creek, and restored the landscape to a more natural setting.

A severe flash flood on July 16, 1963, caused considerable damage downtown and to campsites and picnic areas in Gulpha Gorge Campground. The bridge across Gulpha Creek to Iron Spring was also damaged by a logjam of uprooted trees. Bulldozers were brought in to make repairs and clear rocks and debris from the creek bed. Here, they are clearing the area near Iron Spring.

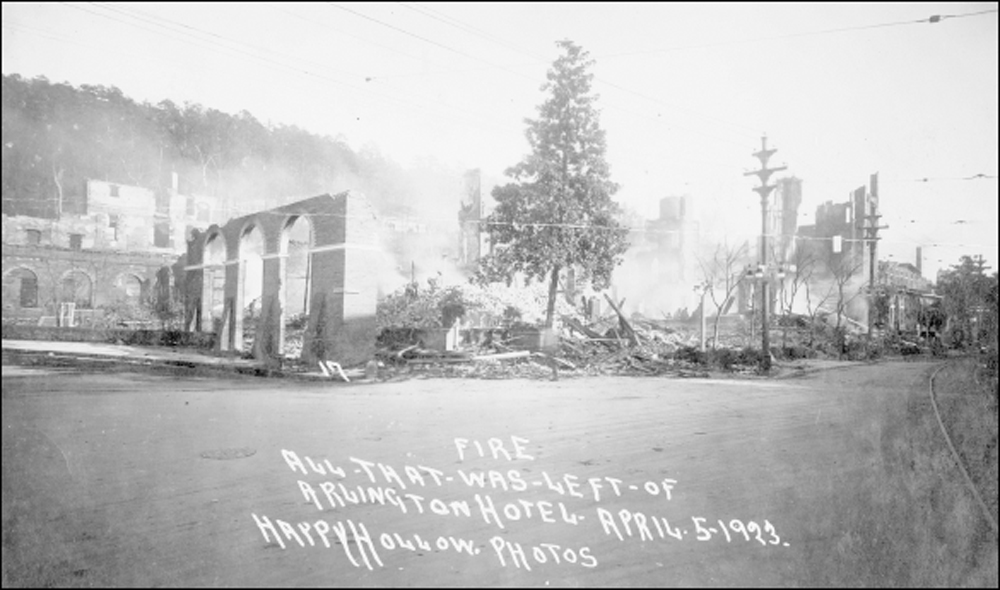

Downtown Hot Springs is seen here in the mid-1920s. The south-facing photograph, showing Central Avenue, was taken from atop the third Arlington Hotel. Arlington Lawn, in the foreground, was the location of the second Arlington Hotel, which burned down in April 1923. The Superior Bathhouse is visible at the far end of the lawn.

Arlington Lawn and the new Arlington Hotel are seen here in the mid-1920s. The photograph looks north from the Superior Bathhouse. The Hoke Smith Fountain is visible to the left at the intersection of the sidewalks. This columnar drinking fountain of white sandstone and marble, with four discharge pipes at its base, was completed in 1897. It was lighted at night to make thermal water continuously accessible to the public.

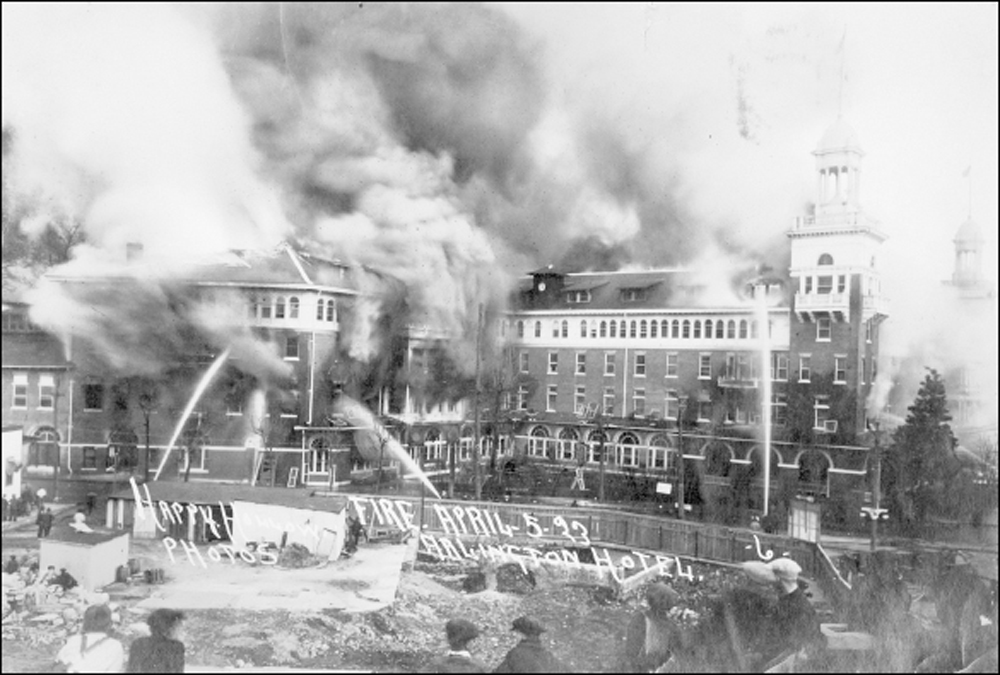

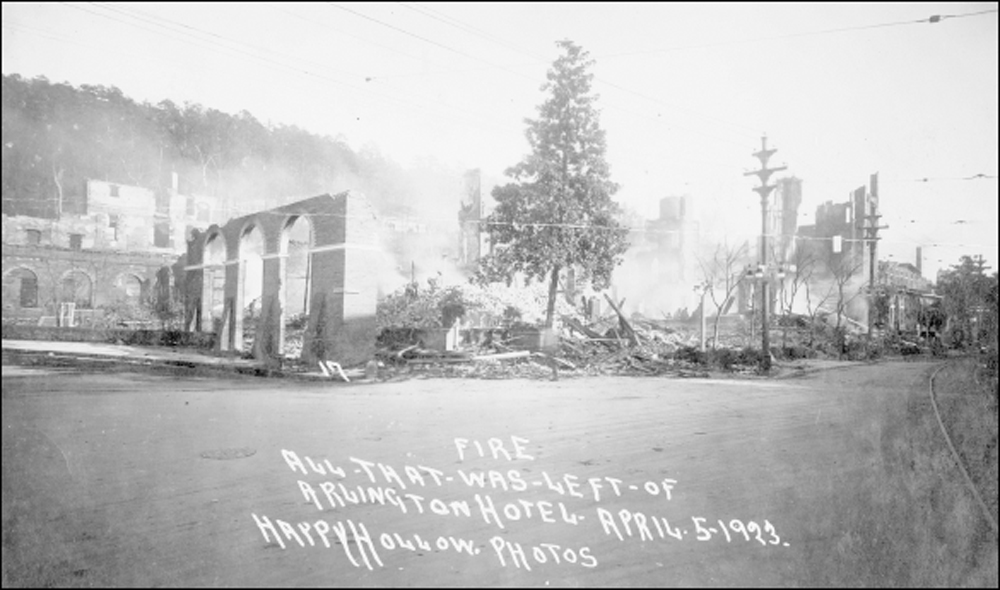

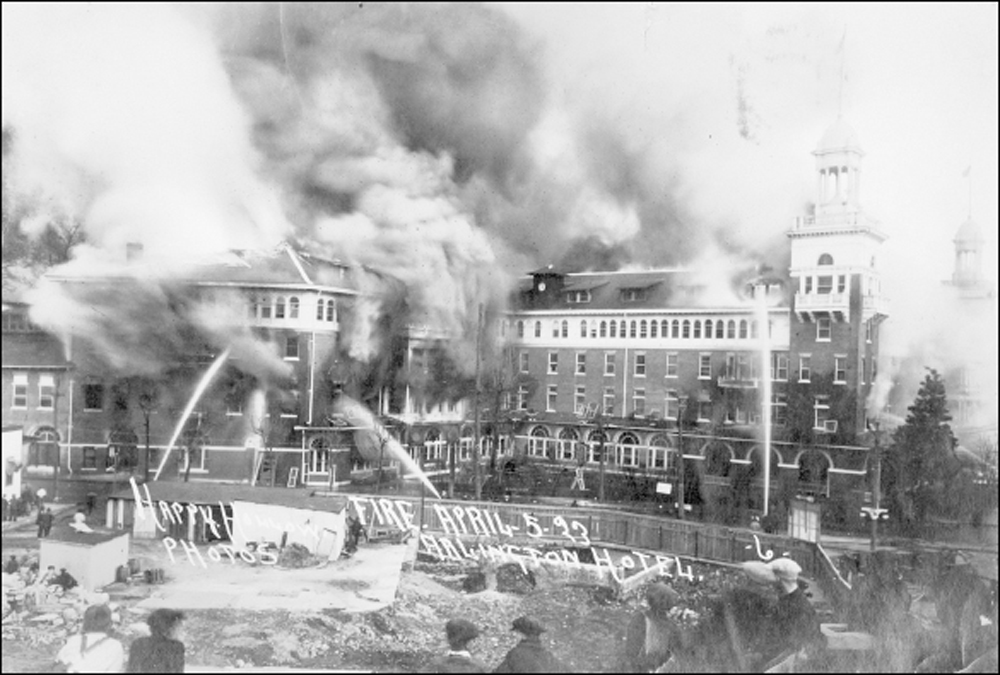

The second Arlington Hotel opened on March 25, 1893. The four-story, red-brick structure built in Spanish Renaissance architectural style replaced the earlier, wooden, three-story version and was called the New Arlington. It featured 300 guest rooms and imposing twin towers flanking its Central Avenue facade. The hotel burned down on April 5, 1923. (Author’s collection.)

Miraculously, despite having around 500 guests registered at the time it burned down, only one person, a 42-year-old Hot Springs fireman named George D. Ford, was killed in the Arlington Hotel fire. He and two other firefighters were caught in the collapse of a brick wall, but the other two men survived the accident. (Author’s collection.)

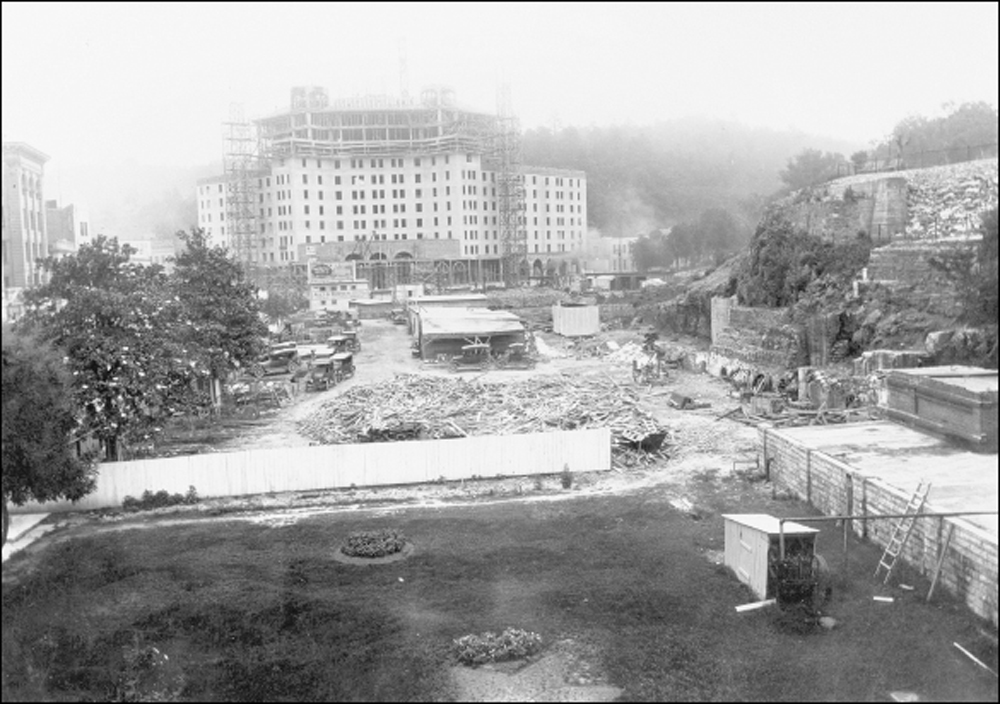

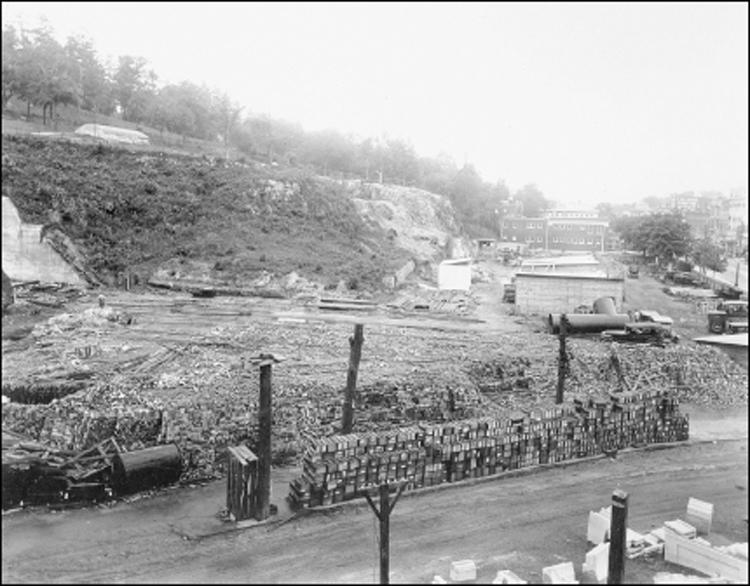

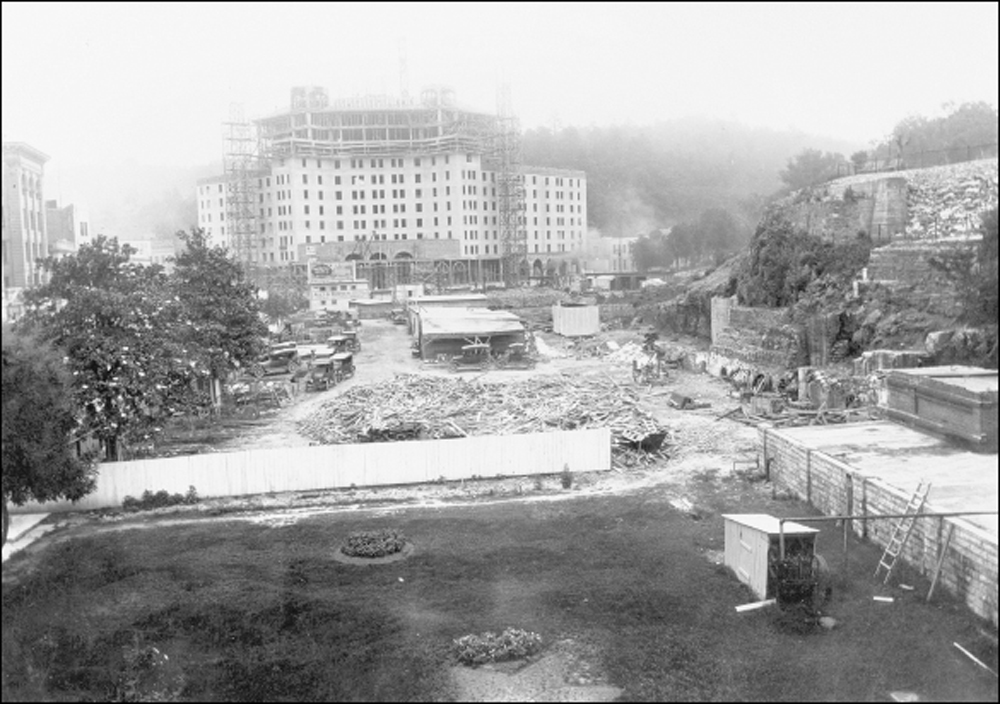

This 1924 photograph of construction of the third Arlington Hotel was taken looking north from the roof of the Superior Bathhouse. The “Texas Star” flower garden is visible in the foreground. The site of the previous two Arlington Hotels is being used as a staging area for construction materials. When the 560-room hotel opened, the site of its predecessors was turned into what is today called Arlington Lawn.

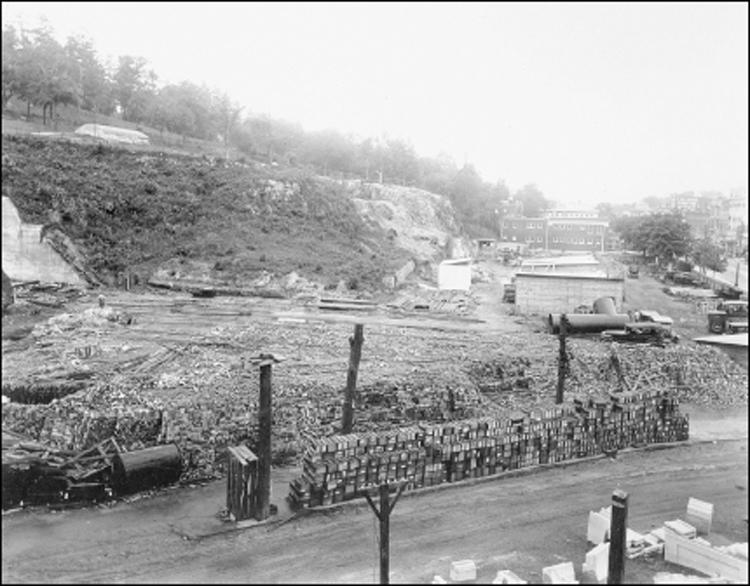

Looking south from the construction site of the third Arlington Hotel in 1924, the Superior Bathhouse is visible in the distance. Building materials as well as brick and debris from the second Arlington Hotel cover “Arlington Lawn” and make Fountain Street almost impassable. The tufa-covered lower slopes of Hot Springs Mountain are also clearly visible to the left of the Superior.

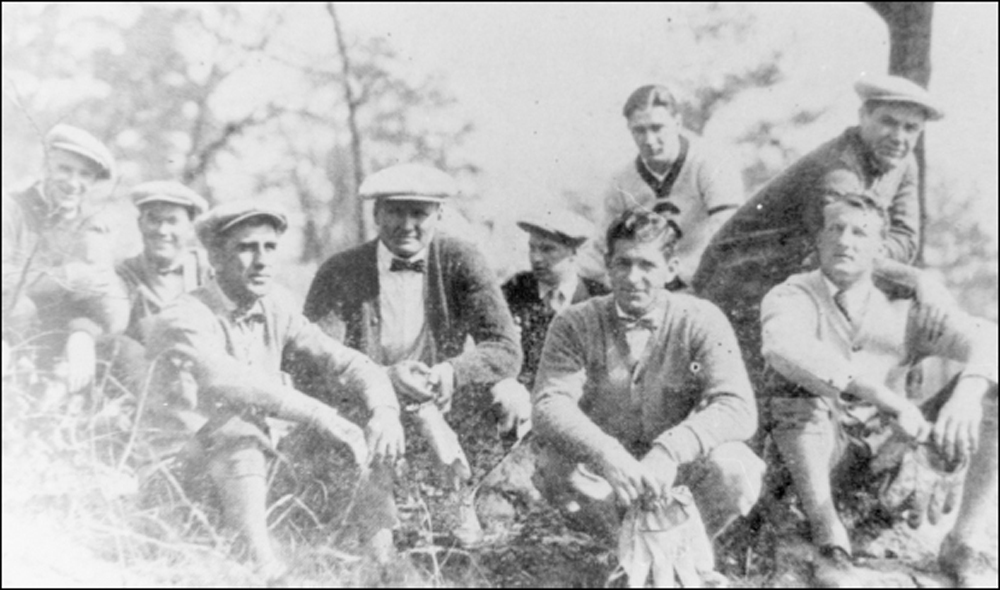

These professional baseball players are hiking on mountains in the park as part of their preparation for the coming season. Hot Springs was the first home of spring training for many major-league teams. Pitcher Walter Johnson of the Washington Senators, fourth from the left, was one of many big-league players who chose to return to Hot Springs yearly on their own for preseason training.

Some big-league baseball teams started coming to Hot Springs as early as 1886 to use the thermal waters and local terrain to train for the upcoming season. Players visited various bathhouses for soaking and massage after practicing at local ball fields. Here, George Livingston Earnshaw, pitcher for the Chicago White Sox, enjoys a steam cabinet in Hot Springs National Park in the 1930s.

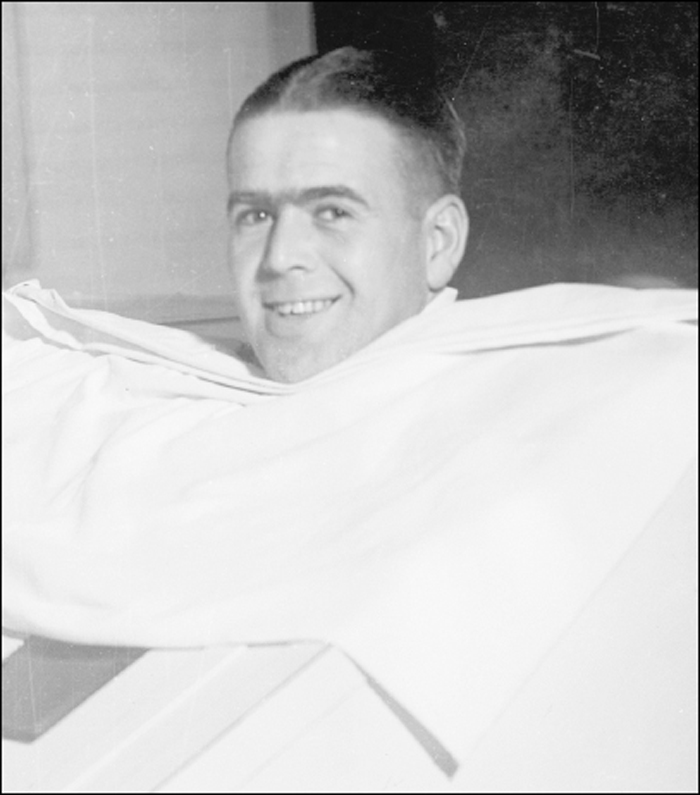

Washington Senators pitcher Earl Whitehill, enjoying his time in the steam cabinet, was one of many players who regularly made the trip to the thermal waters to “boil-out” and prepare for the upcoming baseball season. Not only would the players partake of the baths, they often hiked on the mountain trails to help get in shape.

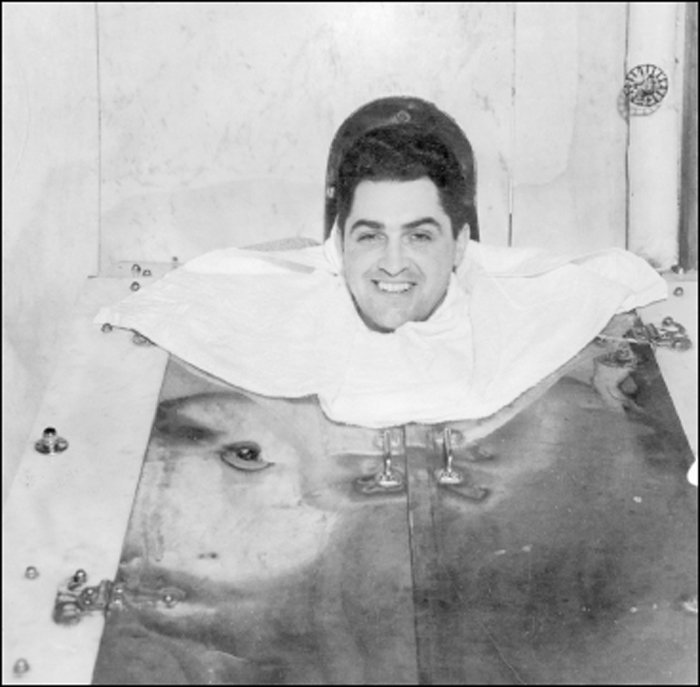

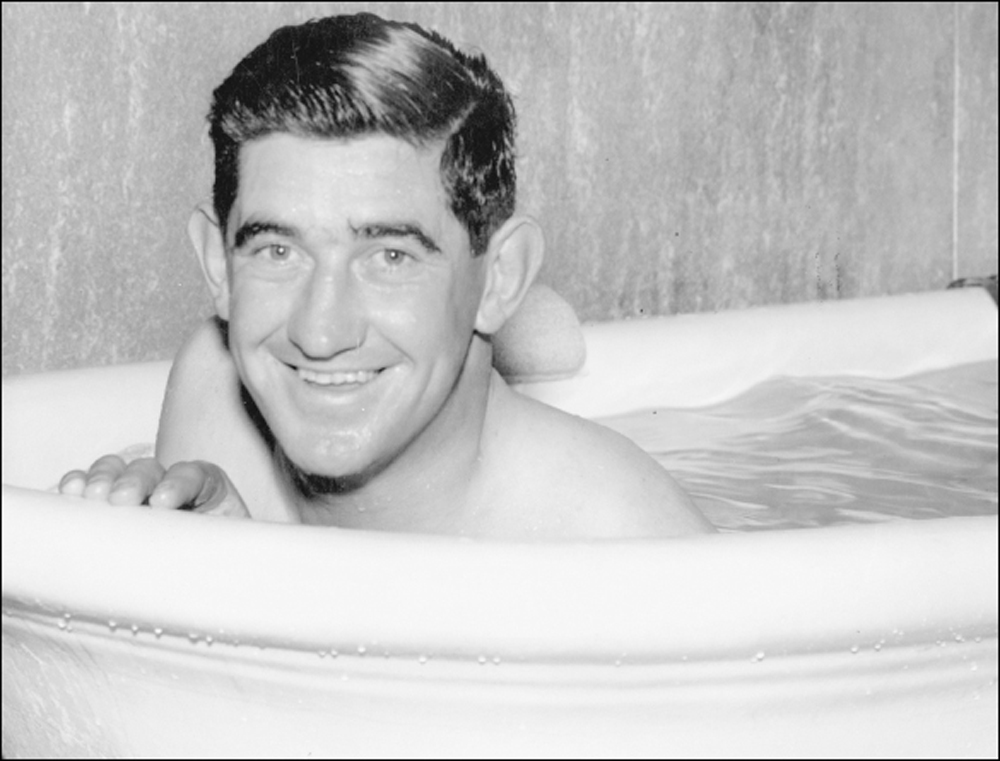

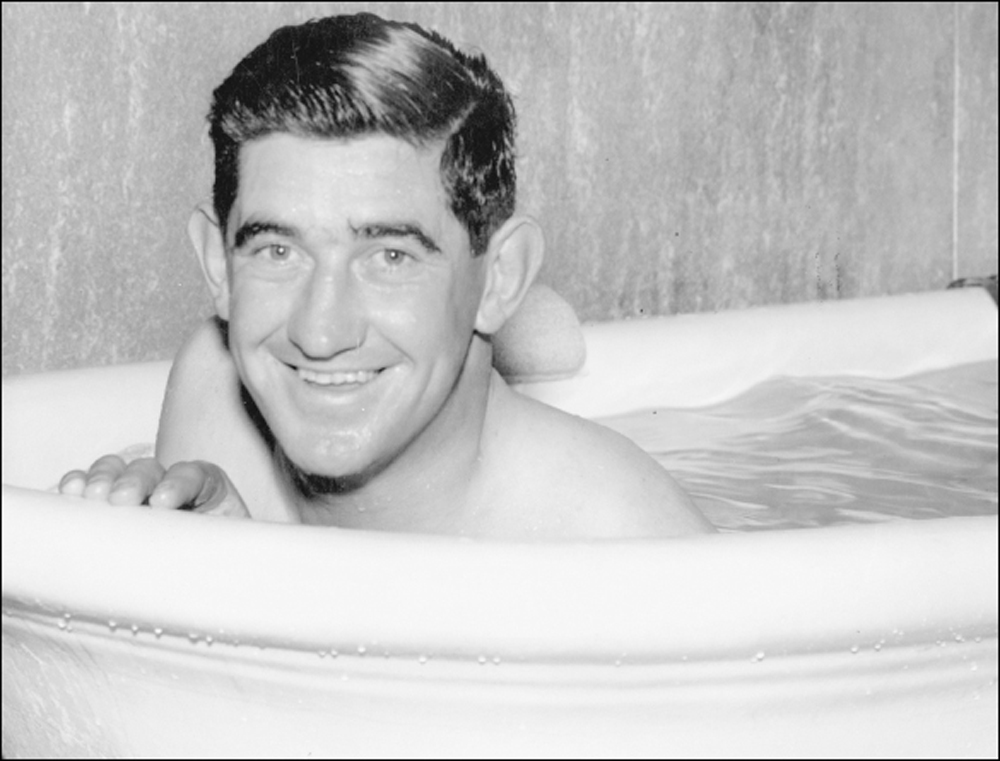

Gordon Stanley “Mickey” Cochrane, player-manager of the Detroit Tigers from 1934 to 1938, has a thermal bath in the Maurice Bathhouse. By the 1940s, teams stopped coming to Hot Springs in favor of other locales, but the city had helped establish the spring-training tradition in major-league baseball.

In late April 1939, while conducting field maneuvers en route to artillery training exercises at Fort Sill, Oklahoma, the 1st Field Artillery Observation Battalion from Fort Bragg, North Carolina, camped briefly at the park’s Gulpha Gorge Campground. Scores of military-issue, two-man pup tents dotted the entire campsite during their stay.

Troops of the Army’s 1st Field Artillery Observation Battalion line up beside their transport vehicles while encamped at Gulpha Gorge Campground on April 26, 1939. Military personnel would be frequent visitors to the park in the coming war years due to the proximity of the Army and Navy General Hospital on the hillside above Bathhouse Row.

This photograph from early 1921 was taken in the pit left behind by the demolition of the Magnesia Bathhouse. The open ground between here and the Fordyce in the background had been vacated by the demolition of the Horseshoe Bathhouse in 1917. These two lots were to be the location of the new Platt Bathhouse, which was renamed the Quapaw Bathhouse before it was completed in 1922.

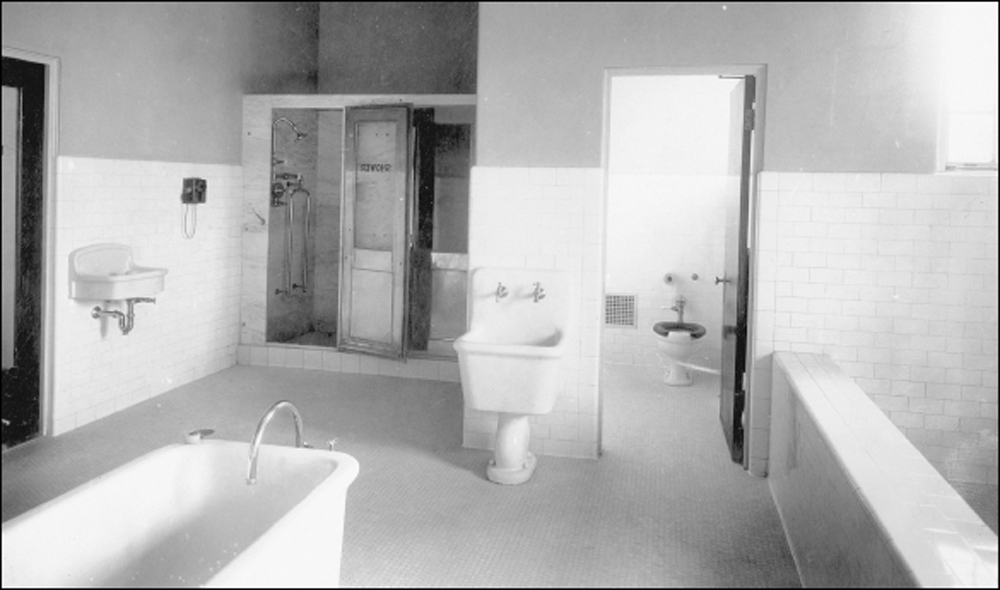

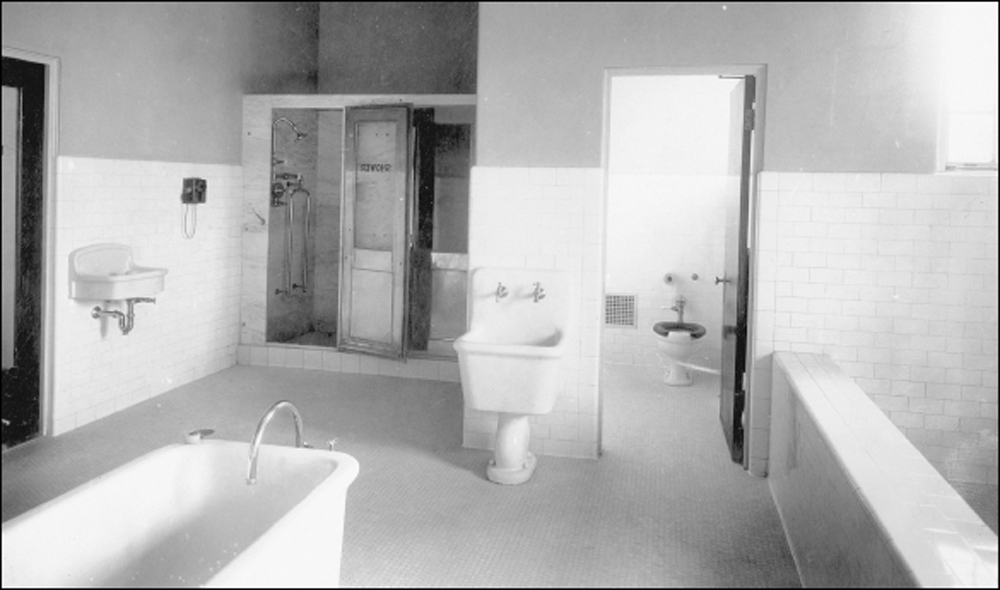

The new Government Free Bathhouse was dedicated on November 14, 1921, and it opened for business the following March. It would be the only bathhouse on government property not on Bathhouse Row. This view shows the fixtures and amenities in one bathing area, including a private toilet and private shower stall.

Hot Springs National Park has always been more than just Bathhouse Row in the historic district downtown. It also encompasses 5,549 acres of forested hills and mountains. To encourage guests to exercise during their visits, hiking trails were carved along the five surrounding mountains. Rangers conducted nature hikes along these trails, such as this trip to Goat Rock in the 1940s with Ranger Irving Townsend and two unidentified visitors.

The US Navy Band from the Army and Navy General Hospital often gave public concerts from atop the Stevens Balustrade after the removal of the bandstand pavilion above. The remnant balcony of the old Navy bandstand is visible to the upper left, and the hospital buildings are evident through the trees in the background.

A quartet of women bedecked in brightly striped bathrobes and holding Hot Springs National Park towels prepares to record a promotional radio spot. The women are, from left to right, Wilda Martin (pianist), Rena Stearns, Alice Freeman, and Marguerite Runyan. They were singing about the “three Rs: Rest, Recreate, and Recuperate.”

Bathhouse Row was often touted in promotional literature as the “Showplace of Hot Springs National Park.” This scenic view is of the wide Magnolia Promenade looking north from the Lamar Bathhouse toward the Ozark Bathhouse in the distance. A row of shade trees lines the sidewalk along its eastern side.

The dome of the Quapaw Bathhouse shines in the afternoon sun in this view looking north along Bathhouse Row. The Arlington Hotel is visible in the distance. By this time, the row of shade trees along the east side of the sidewalk have been removed, with only the magnolias along Central Avenue and a few of the American holly trees on the lawns remaining.

This photograph of Bathhouse Row, looking north along Central Avenue, dates from the 1950s. The old Army and Navy General Hospital is on the hillside to the right, and the Arlington Hotel and Medical Arts Building are seen in the distance on the left. The south entrance to the Grand Promenade, at this time still a simple wooden stairway, is visible at the right edge.

The park’s campground and picnic area along Gulpha Creek have always been utilized heavily by the public. This scene from the late 1950s shows the range of users, from tents to trailers. As automobile travel increased after World War II, the campground continually evolved to accommodate a more mobile society.

When the Prospect Avenue entrance to West Mountain Drive was completed in November 1941, motorists could access the mountain from farther west along Prospect Avenue than in previous years using the Hawthorn Street entrance. Although it has changed in appearance over the years, this is still the southern entrance to West Mountain.

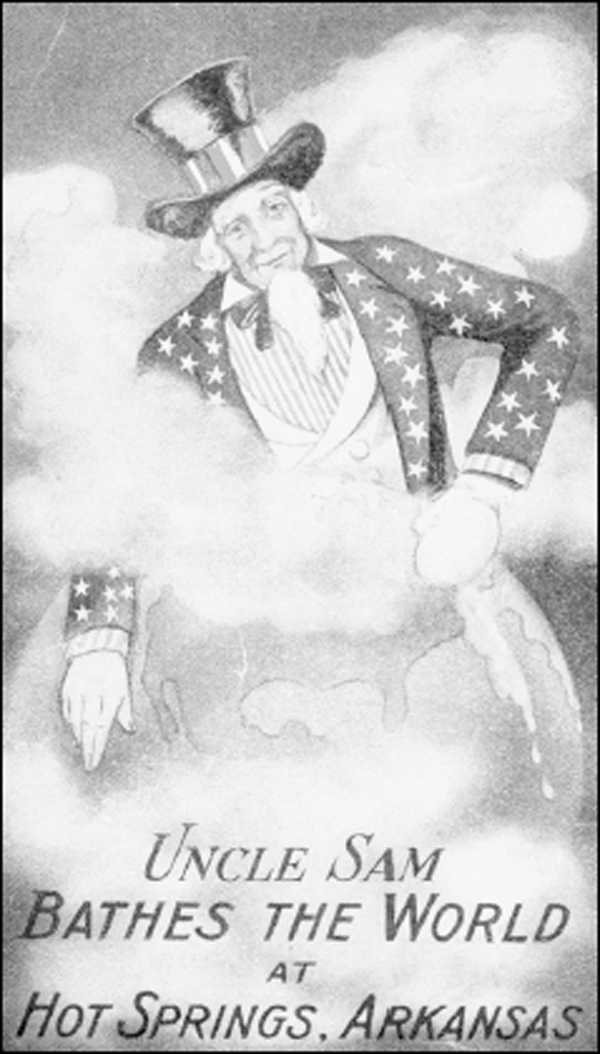

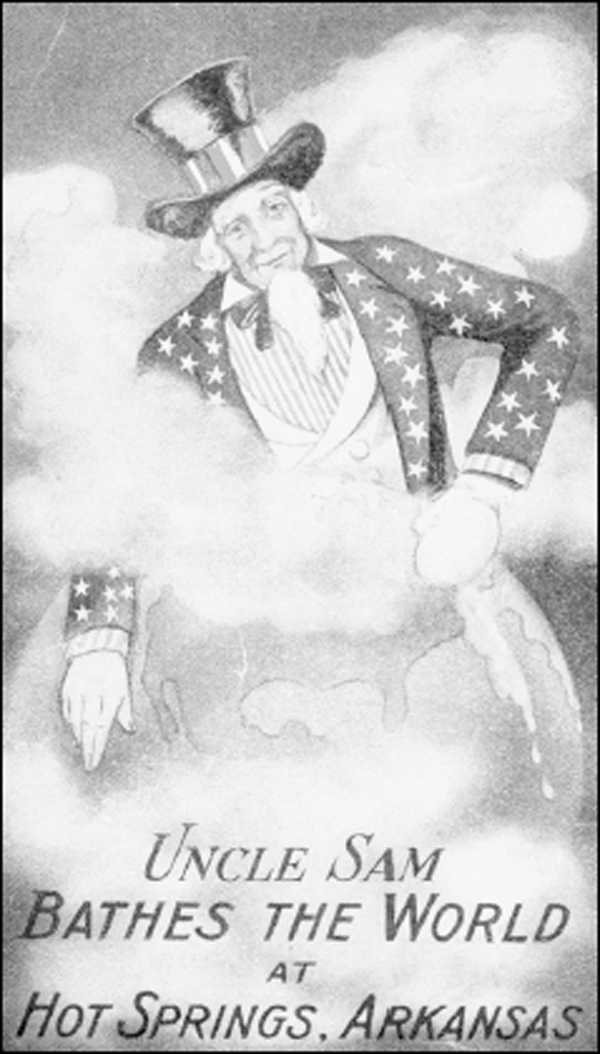

Promotional materials and advertisements for Hot Springs National Park have for years featured Uncle Sam with the slogan “Uncle Sam Bathes the World at Hot Springs, Arkansas.” The bathing industry frequently capitalized on the fact that the federal government was regulating and controlling the thermal water and its use, making it safe for patrons.

Quapaw Bathhouse attendant Voncile Payton takes care of a bather in the 1950s. Bathhouses utilized bathing attendants as early as 1875 to provide patrons with personal assistance and individual therapy. By 1910, the federal government issued regulations limiting the amount of work an attendant could be assigned. The majority of bathing attendants were African Americans, who were not allowed to use most of the bathhouses along Bathhouse Row until after desegregation.

Bath attendant Iola Bedford (above) worked in the ladies areas of the Maurice Bathhouse for many years. Here, she is placing a cool towel on the forehead of a female patron resting in the pack room. Bath attendants monitored and timed baths and other activities to ensure the safety of patrons. They also served cooled thermal drinking water as part of the regimen. Attendant Ernestine Guinn (below) assists two ladies undergoing treatment in vapor cabinets. Other cabinets nearby offered a “dry” heat treatment, meaning they contained numerous lightbulbs for generating heat rather than using thermal water vapor.

A bath attendant in the Ozark Bathhouse helps a patron enter a stainless-steel whirlpool tub in 1960. The bathhouses in Hot Springs were constantly adding new technologies and treatments to provide their users with the latest therapies. This was done not only to contend with other facilities in town, but to compete with other spas around the country.

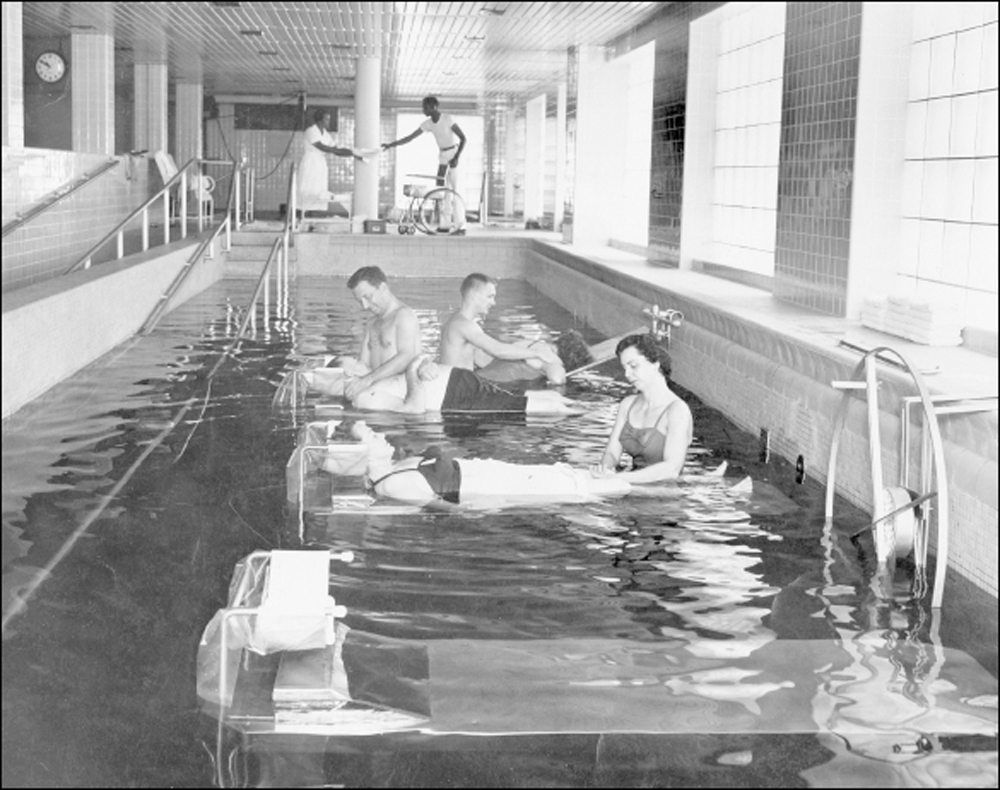

The Physical Medicine Center in the Libbey Bathhouse on Spring Street featured several large pools to accommodate multiple patients and their physical therapists simultaneously. Here, three therapists are working with their patients in a first-floor thermal pool, while attendants in the background prepare to help the patients with limited mobility out of the water.

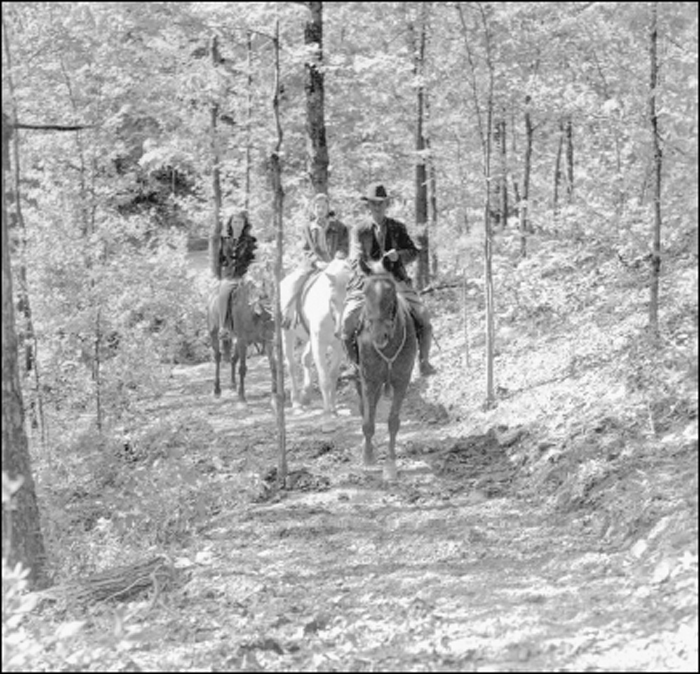

From 1892 to 1911, trails on Hot Springs Mountain and North Mountain were developed and improved to encourage visitors to hike or ride horses for exercise on parts of the mountains not accessible by roads. The outdoor exercise regimen was encouraged as part of a holistic approach to visitor health and wellness.

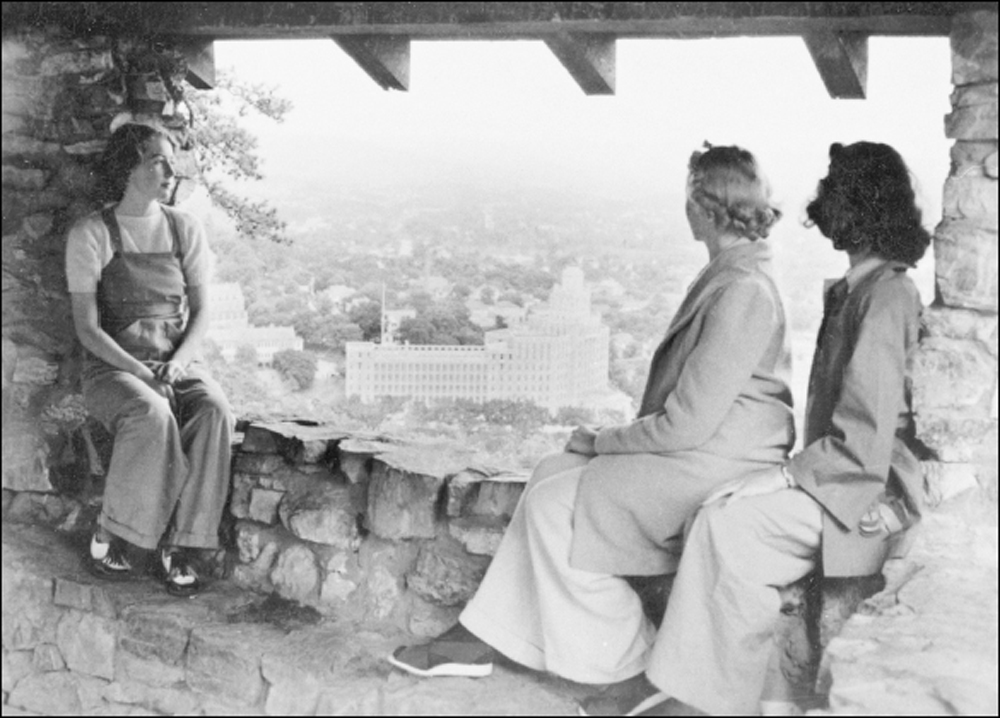

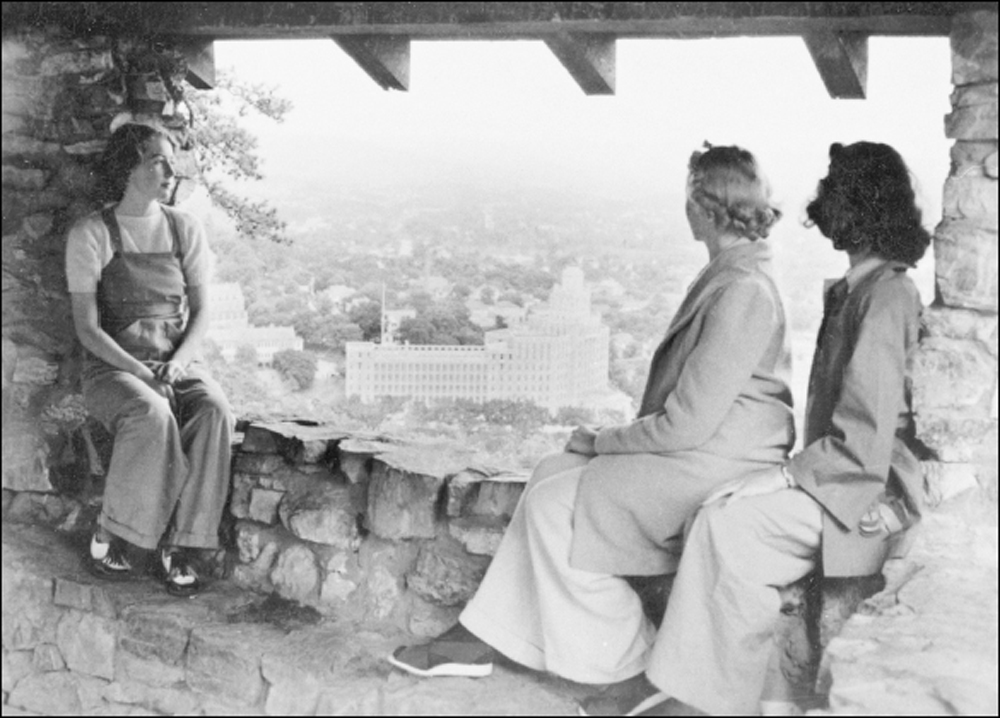

Shelter houses were built on the park’s mountains over the years to provide places for visitors to relax and view the valleys below. This stone shelter pavilion, built in 1924 on West Mountain, overlooks Bathhouse Row and the old Army and Navy General Hospital campus. The shelter is still in use today.

The Quapaw Bathhouse was built in 1922 and remodeled in 1929 and 1968. It closed for business in 1984. It was designed by architects Mann and Stern of Little Rock and cost $214,837 to build. Called the Platt Bathhouse during the design phase, the Quapaw stands where the Horseshoe and Magnesia Bathhouses used to be.

When the Army and Navy General Hospital complex was passed to the State of Arkansas in 1959 to be used as a vocational school, two duplexes and their garages on Reserve Avenue were retained for use by Hot Springs National Park. The former Medical Director’s Residence was also conveyed to the park. Today, this duplex is used for offices by the law enforcement division.

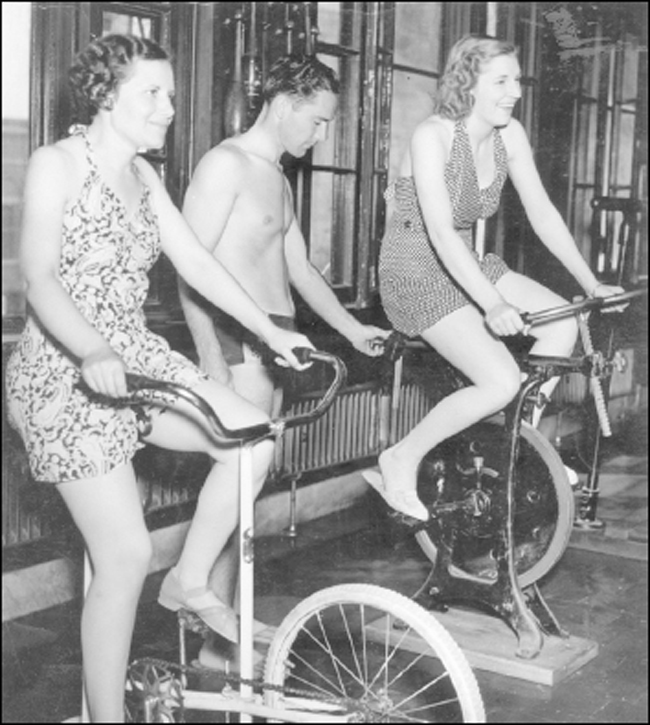

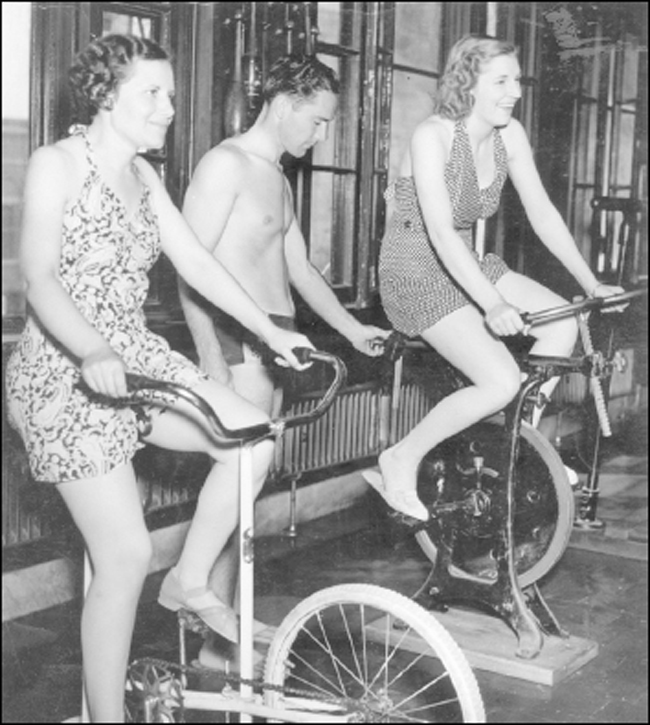

The Roycroft Den on the third floor of the Maurice Bathhouse served a variety of purposes over the years, including, for a time, as the gymnasium. Here, two women pedal on exercise bicycles while a male bathhouse attendant adjusts the pedal tension on one cycle. When the new Maurice was remodeled in 1915, this room replaced the solarium that had been in the original building when it opened in 1912.

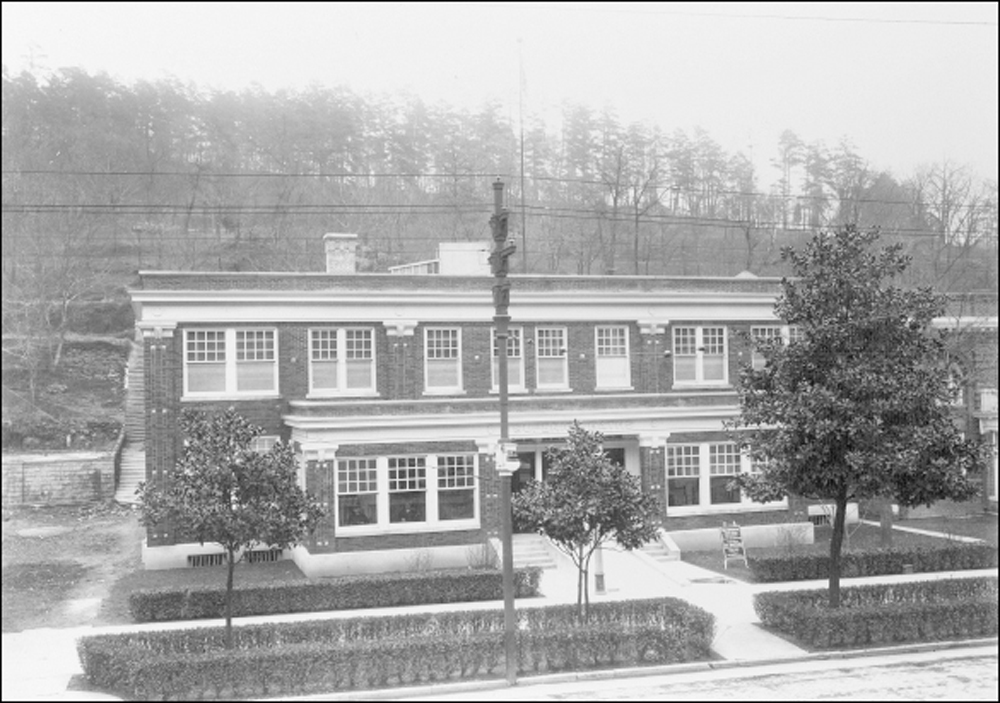

Architect Erskine Sunderland developed the plans for a new brick residence on Reserve Street for the park’s medical director, Harry Hallock, in 1912. A Hot Springs contractor, Michael H. Jodd, won the building contract with his bid of $22,001. All through its construction, the cost of the house drew negative publicity. Dr. Hallock moved his family into the completed residence in February 1913.

The John W. Noble Fountain, named after the secretary of the interior who provided funds to help renovations in the park, was initially placed at the corner of Central Avenue and Reserve Street in 1895. In 1945, the fountain was moved to the sidewalk in front of the new Administration Building. It was a convenient resting place for pedestrians along Central Avenue.

Opening on February 1, 1912, the Buckstaff Bathhouse was a new masonry building that replaced the wooden Rammelsberg. Furnished with modern hydrotherapy equipment and a gymnasium, the new bathhouse was a popular business. Shown here is the interior of the men’s waiting room, with a marble sink and tiled floors. The door at the back leads to a writing room.

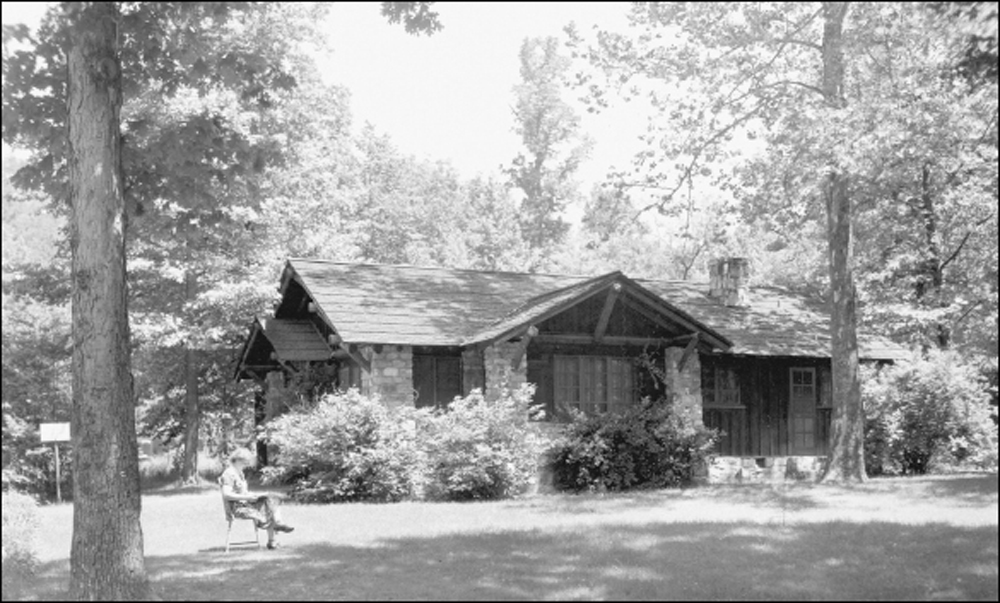

Built by the park’s maintenance workers in 1932, this stone cabin was initially used as a residence for the caretaker of Gulpha Gorge Campground. Visitors would sign in on the front porch of the cabin. Later, its garage was converted into a registration station for campers. The cabin has also been used as a park ranger residence, but is now reserved for the artist-in-residence program and for Volunteers-In-Parks (VIP) personnel.

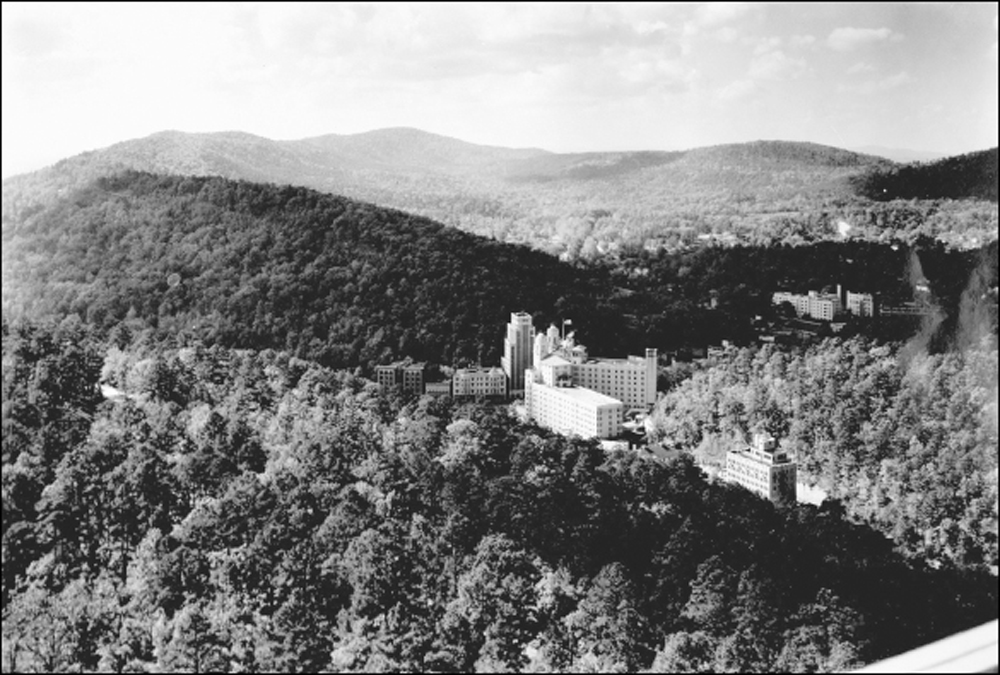

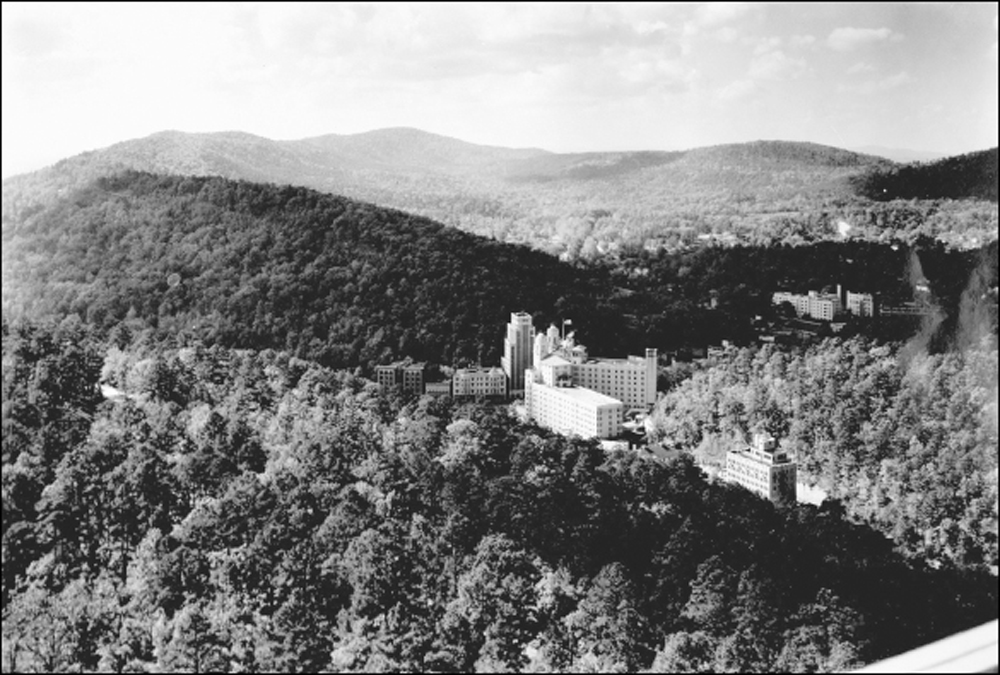

Positioned between the large and expansive Eastman Hotel on the south (bottom) end and the Arlington Hotel at the upper center, Hot Springs National Park lines Central Avenue, with its jeweled bathhouses. Hot Springs Mountain on the right, West Mountain on the left, and North Mountain to the top surround the downtown area with their scenic beauty.

Park visitors enjoyed many outdoor leisure activities, such as riding in horse-drawn carriages on the roadway to the top of Hot Springs Mountain. This scenic journey presented them with stunning views of downtown, including the Arlington Hotel (right) and the new Medical Arts Building across the street.

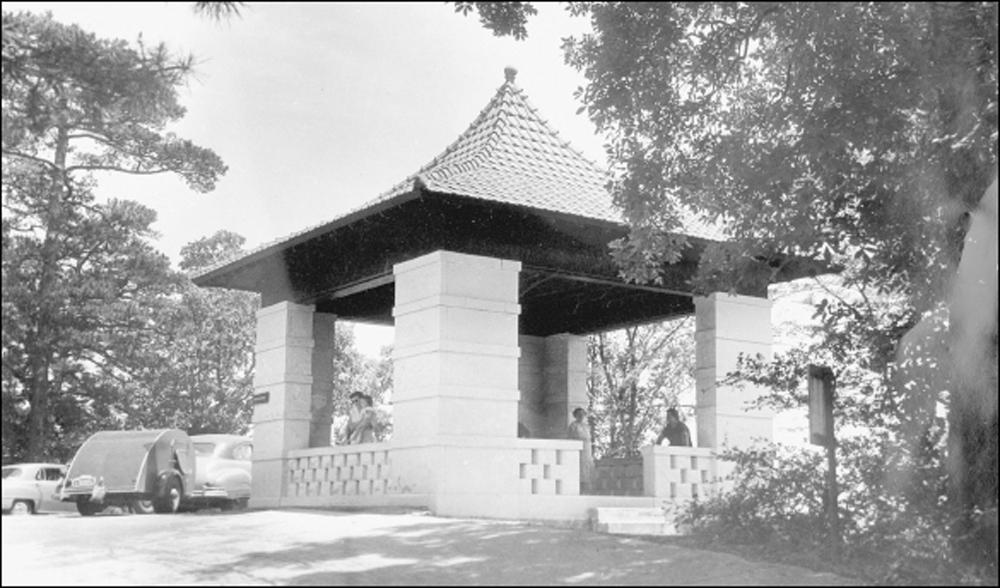

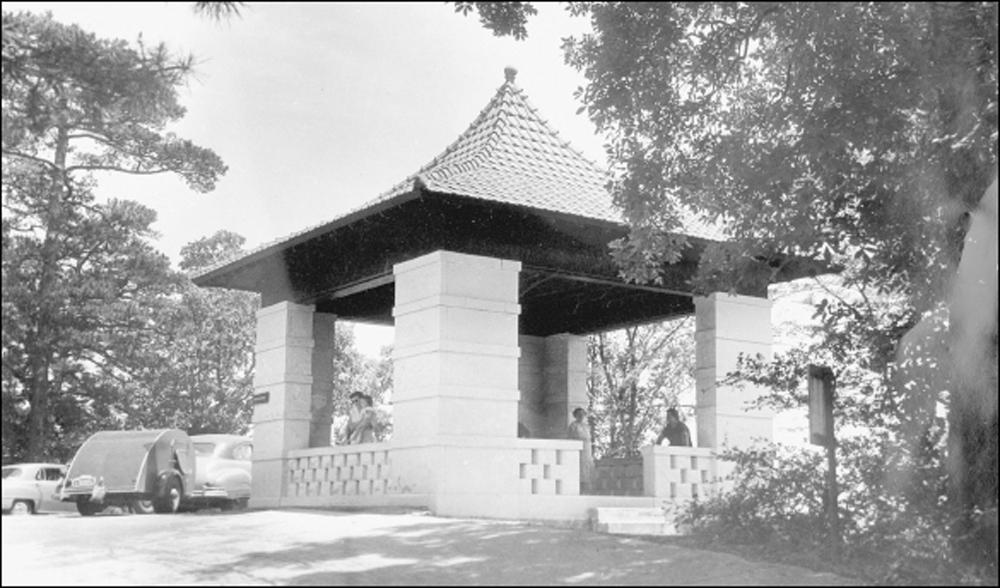

This 1940s photograph belies the age of the Hot Springs Mountain Pagoda. Designed by architect J.G. Horn in 1911 for Lookout Point, the pagoda, with its distinctive roofline, has become an enduring icon of the park. Unfortunately, it has been plagued by vandalism since its installation. In 1914, a sign was installed listing the legal ramifications of defacing the shelter.

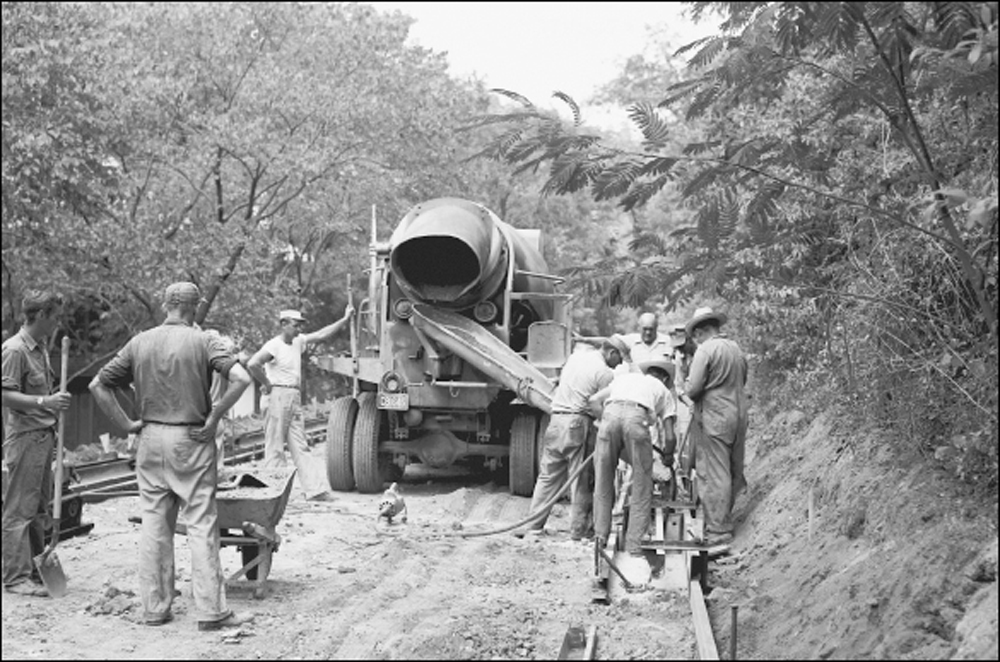

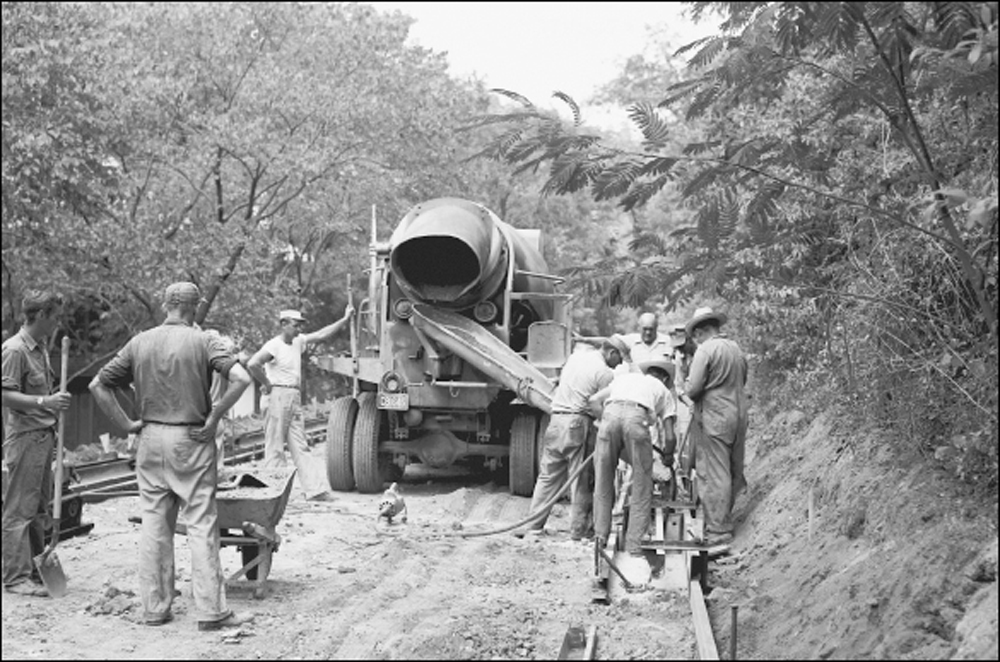

Above, workmen pour concrete for the construction of the Grand Promenade walkway on the hillside above Bathhouse Row. Started in 1932 as a graded dirt roadway, the route took several years to complete. Plans for the strolling path evolved over time, and in 1942 over 370 linear feet of brick paving stones were installed on a portion of it. Below, the Grand Promenade was finally completed by 1958 with the installation of plants and lighting. This picturesque walking trail presented several resting places for park patrons, some even offering tables with built-in tile chessboards. Visitors could relax and take in the natural beauty of the surrounding mountainsides above the city.

After the old Government Free Bathhouse located behind Bathhouse Row was closed, a new and final Government Free Bathhouse was constructed in 1921 on a triangle of land at the intersection of Reserve and Spring Streets. In the foreground is the Army and Navy General Hospital gate and perimeter fence.

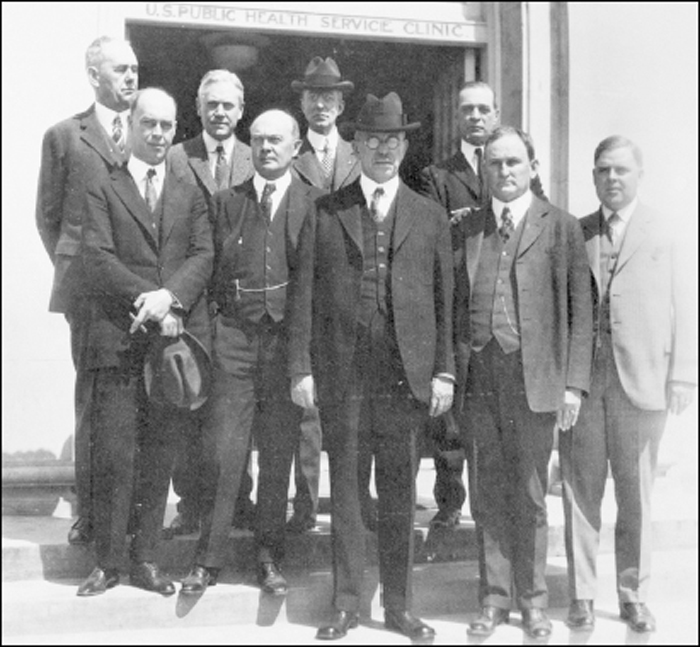

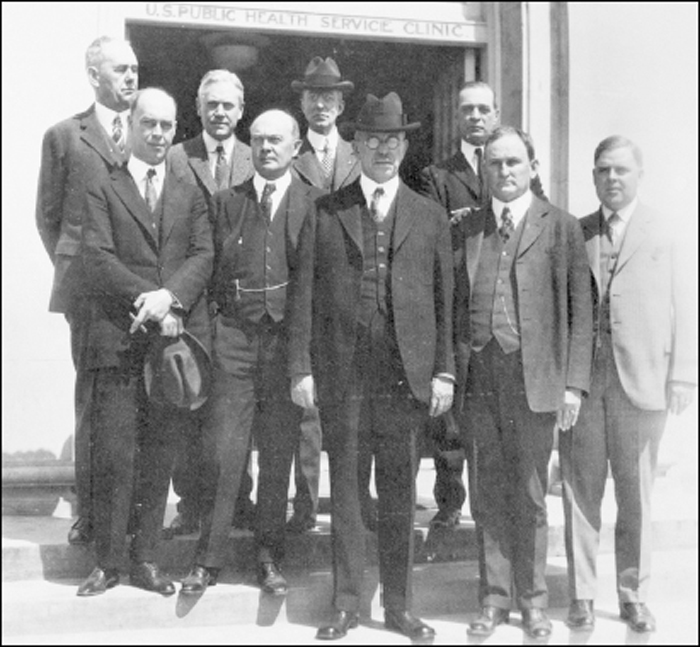

The grand opening of the Government Free Bathhouse was celebrated on November 14, 1921, with NPS director Stephen Mather (second row, second from left); Dr. Hugh Cumming, head of US Public Health Service (second row, third from left); Dr. Hubert Work, postmaster general (first row, third from left); and Arkansas senator Joseph T. Robinson (first row, fourth from left). The other unidentified gentlemen were members of the Arkansas congressional delegation.

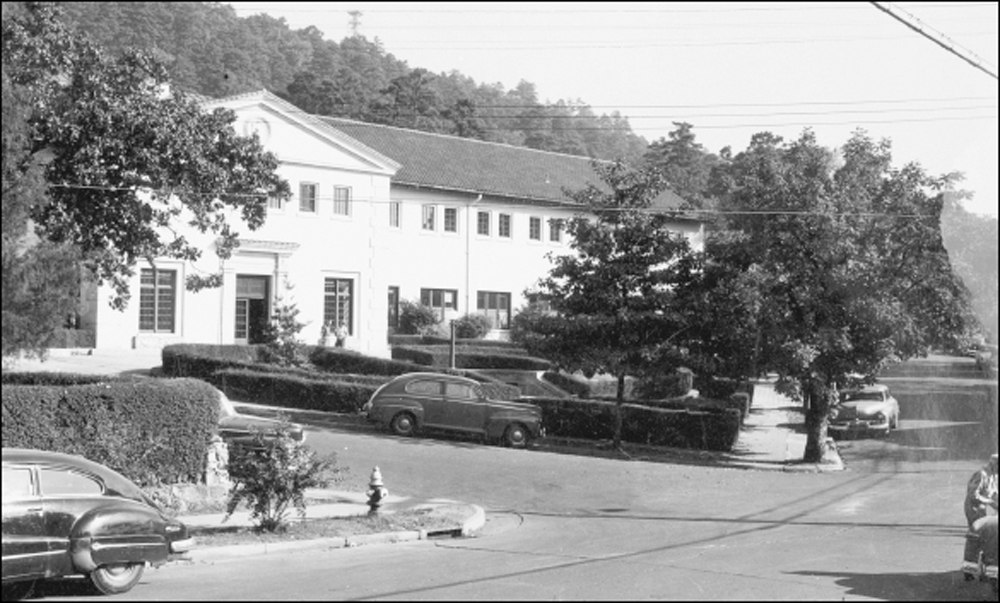

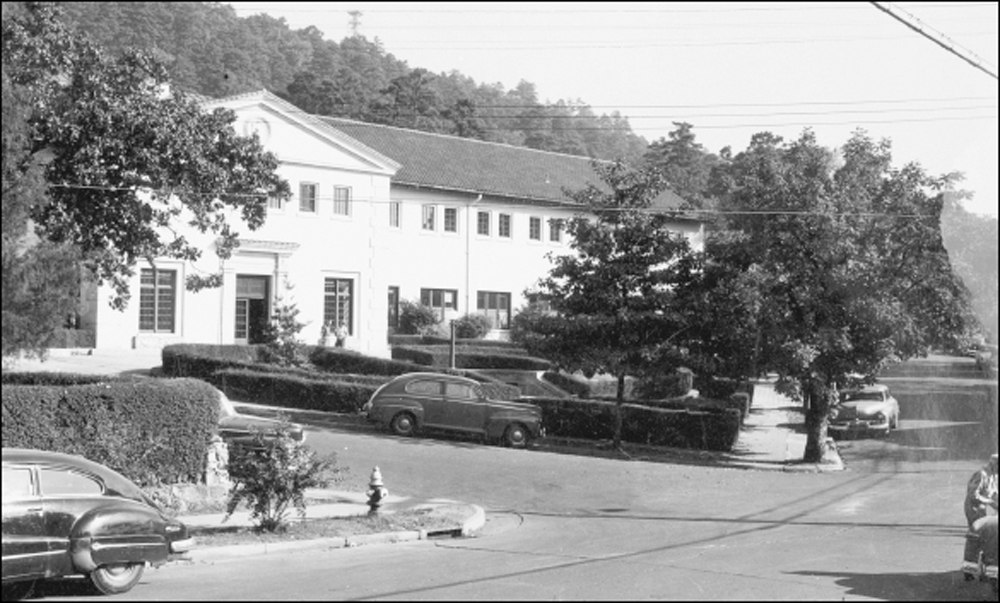

The new Roman Revival-style Government Free Bathhouse across Reserve Street from the Army and Navy General Hospital featured individual tubs as well as communal pools, as shown above. Led by US Public Health Service (PHS) doctors, treatment of a variety of physical ailments was available. The top floor of the two-story building housed the Government Free Bathhouse, while the lower floor contained the PHS venereal disease clinic. The Government Free Bathhouse offered the most modern equipment for therapeutic bathing, such as the stainless steel Hubbard tubs with whirlpool attachments seen below. The bathhouse offered bathing for indigent patients and African American patrons.

Many indigent and transient people traveled to Hot Springs to receive treatment at the Government Free Bathhouse (shown). In response to overcrowding, the Hot Springs Federal Transient Bureau was established to help people who had been displaced by the Depression. The bureau built Camp Garraday, a fenced enclosure with barracks for housing many of the male transients. Females and married couples were settled in hotels or boardinghouses.

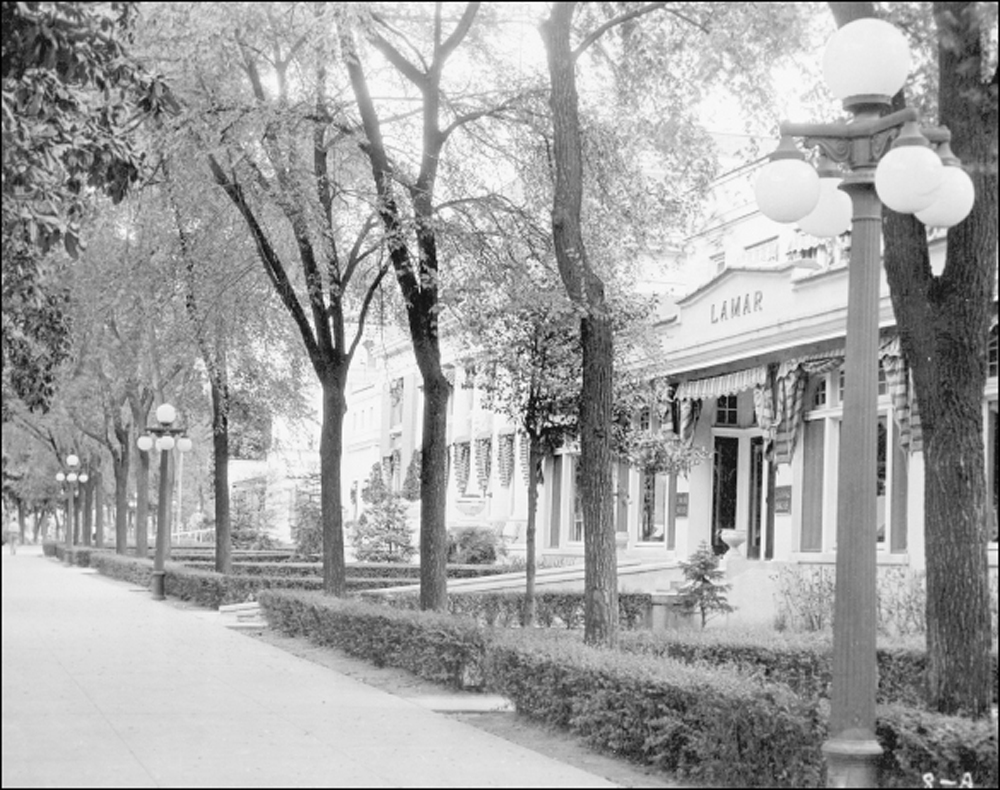

The manicured lawns and trimmed holly hedges of Bathhouse Row in the 1940s denote the success of the bathing business. Shown here are, from near to far, the Lamar, the Buckstaff, and the twin towers of the Ozark Bathhouse. The electric light posts were installed in 1914 with five globes on each light standard.

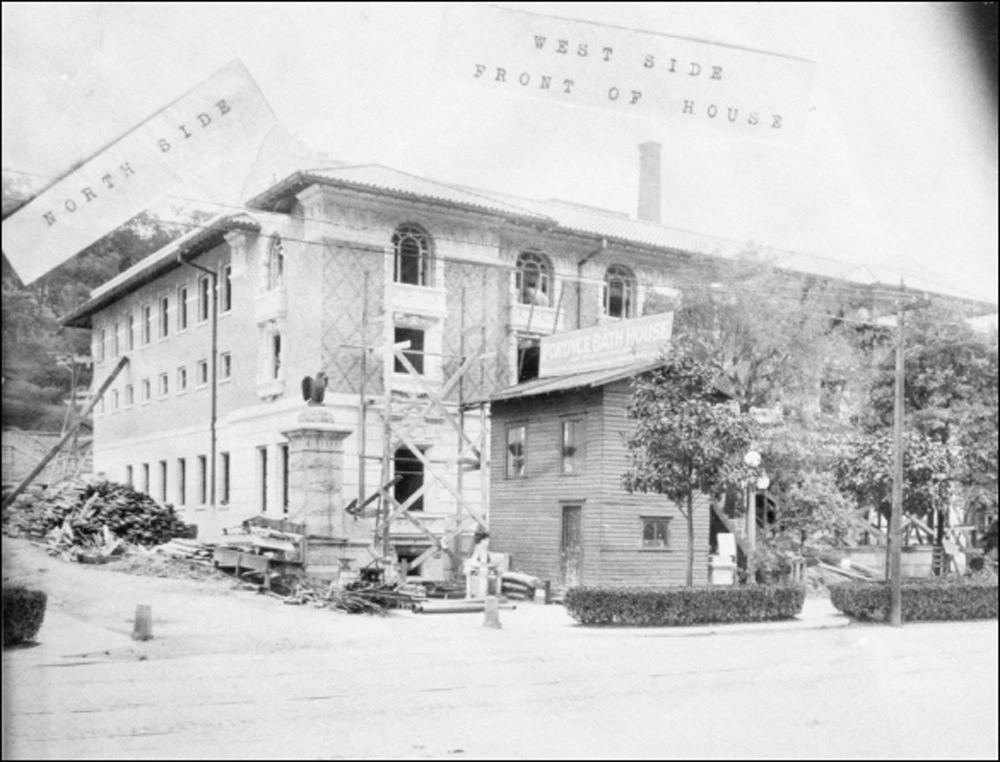

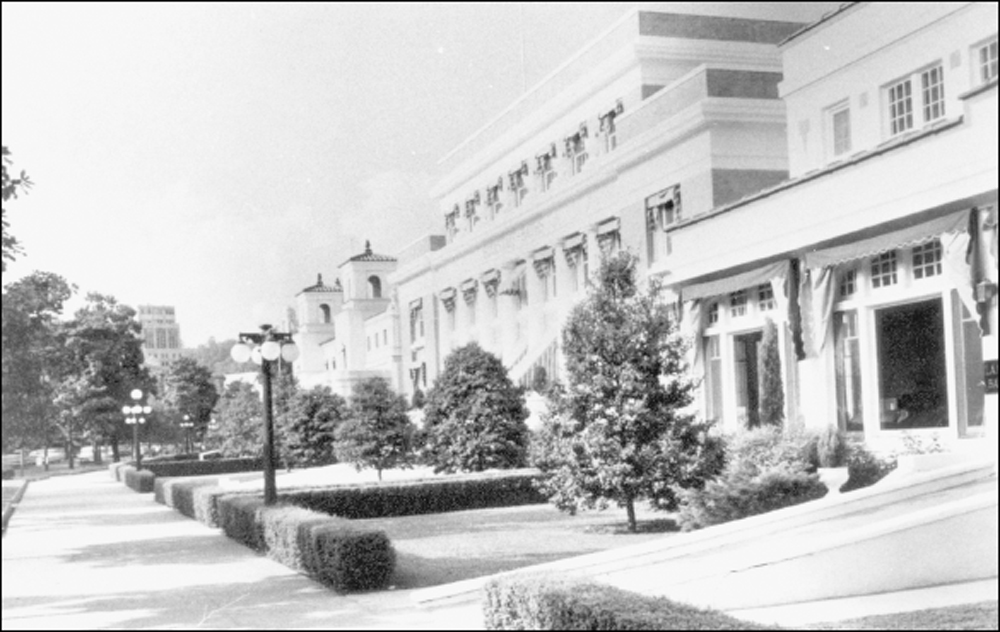

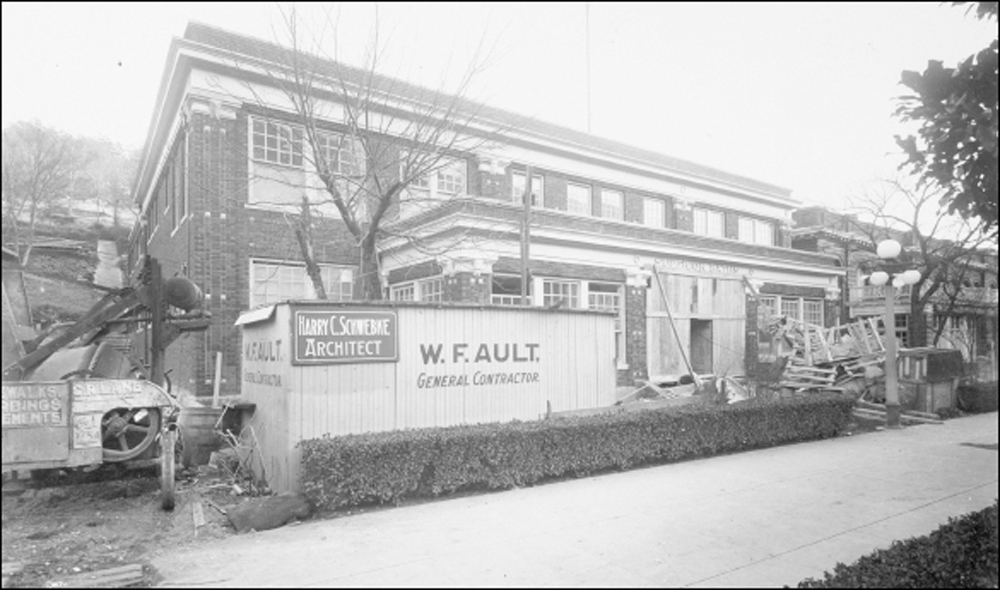

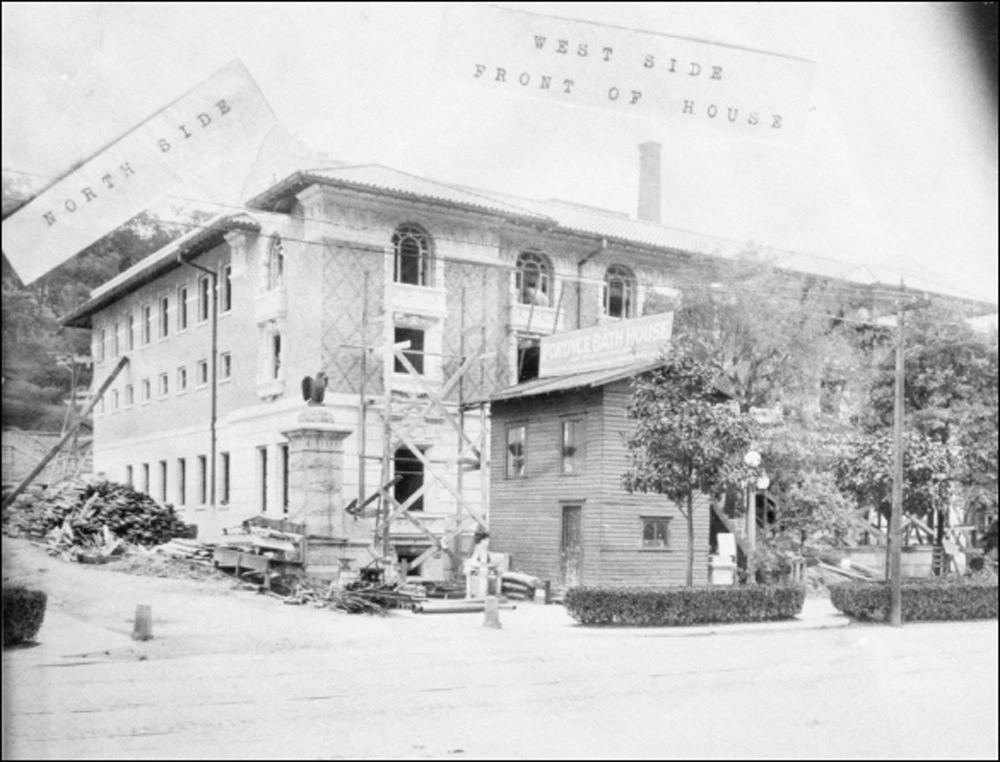

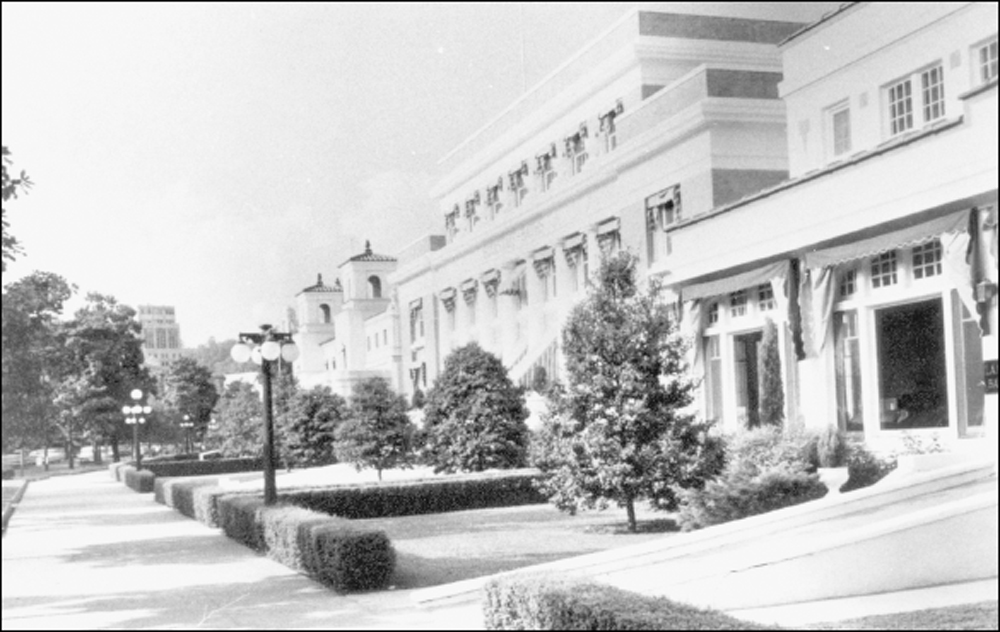

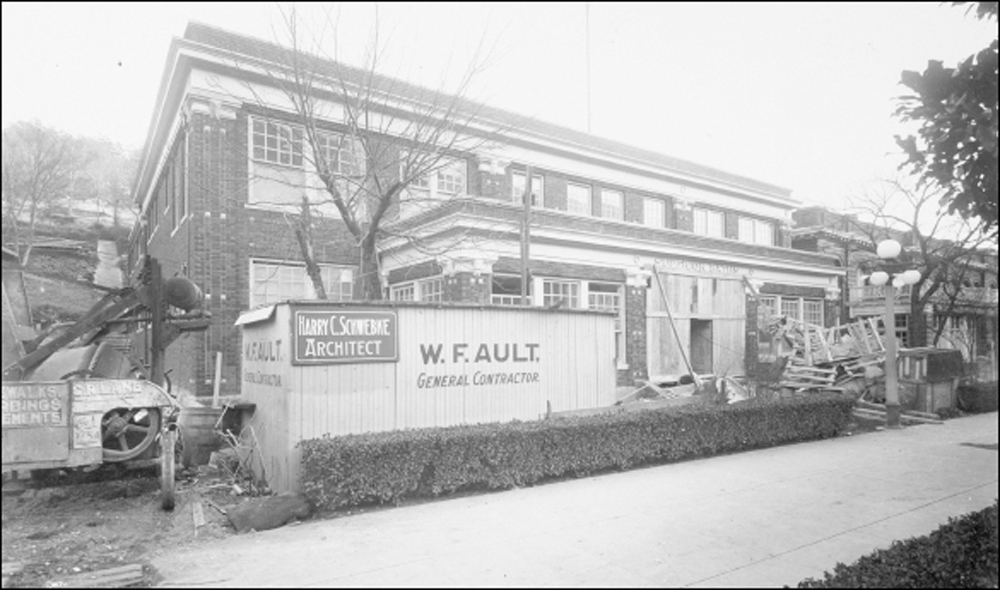

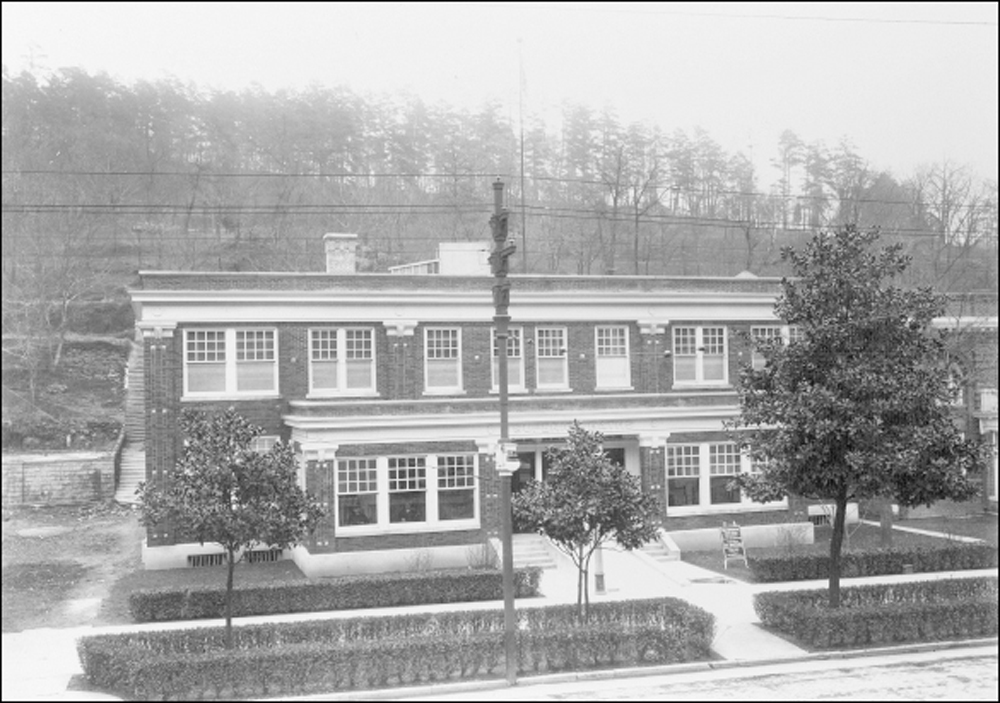

Designed by architect Harry C. Schwebke and built by W.F. Ault, the new Superior Bathhouse was begun in 1915 (above) and completed at a cost of $68,000 (below). The building that had been erected in 1888 failed to meet the Department of Interior’s rules for bathing establishments and was closed and subsequently demolished. The new 11,000-square-foot Superior Bathhouse building opened for business on February 16, 1916, and offered moderately priced baths for consumers. As the smallest bathhouse on federal property, the Superior offered only the basic hydrotherapy, mercury, and massage services. It closed its doors in November 1983.

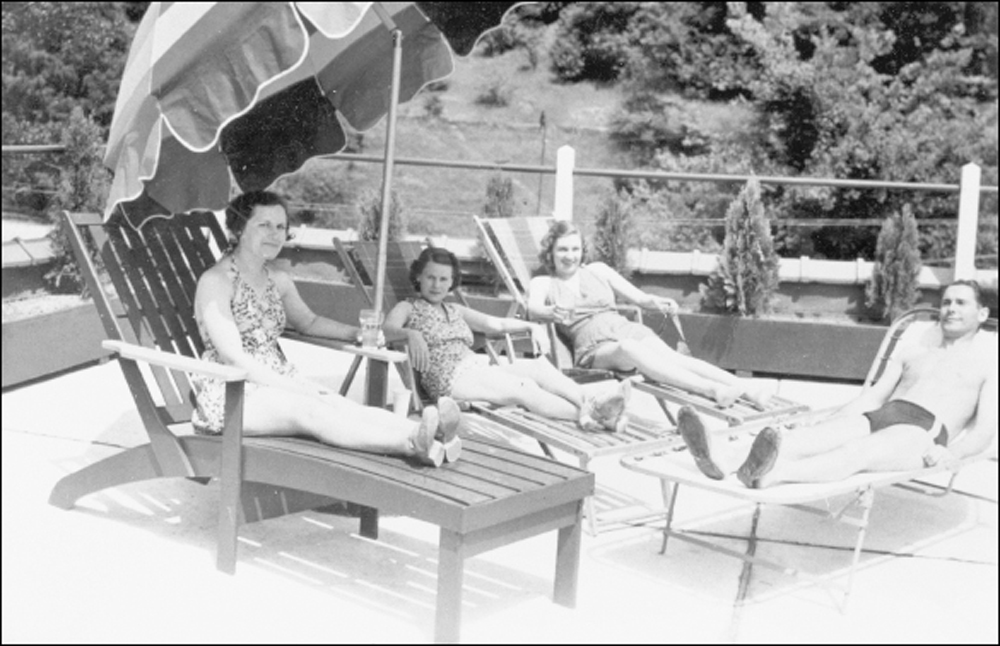

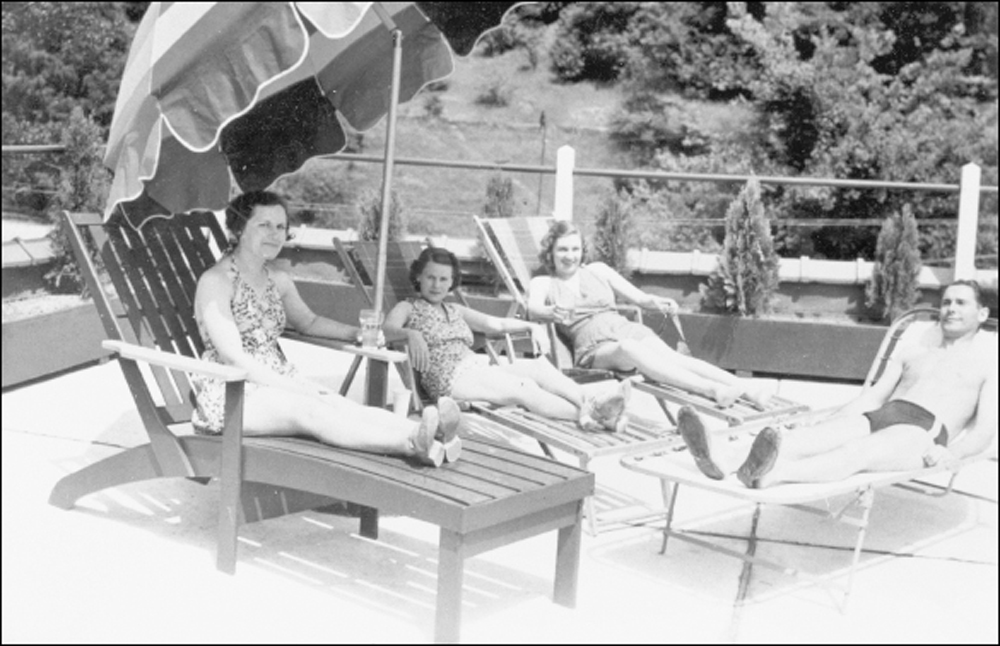

Samuel Fordyce’s bathhouse was one of the few facilities that installed a roof garden for its patrons to partake of either sunbathing or relaxing with the scenic view. A private area located on the second-floor men’s side allowed nude sunbathing for men, but it was eventually phased out. The roof garden was accessed through a stairway on the third floor.

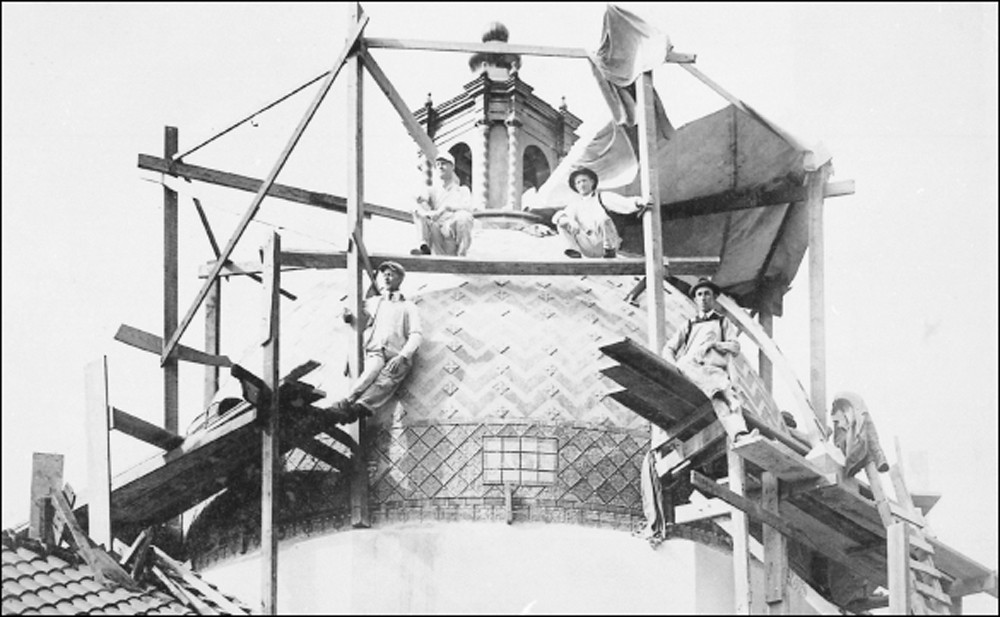

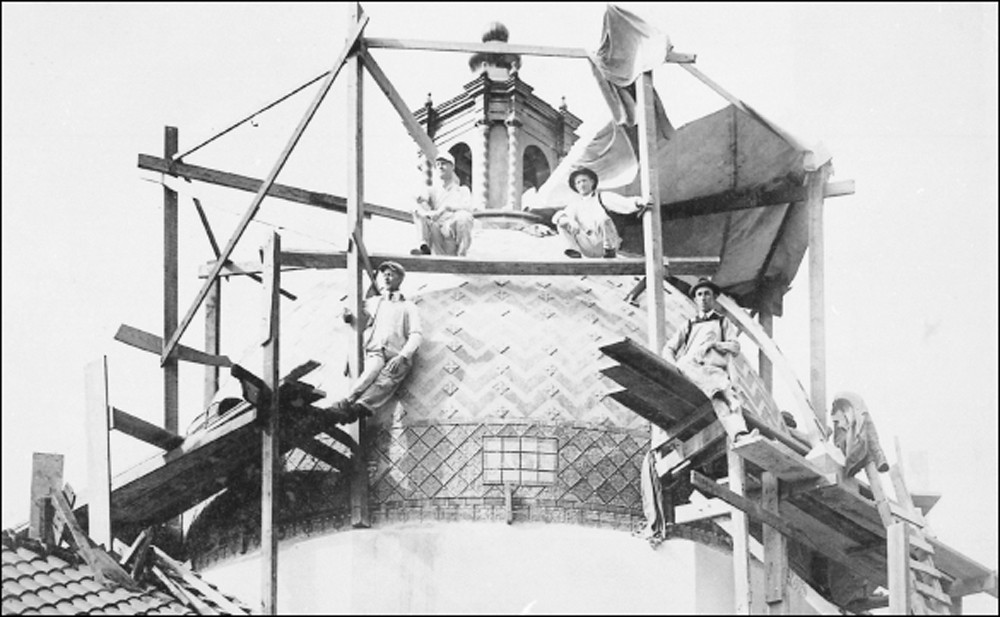

The Spanish Colonial Revival Quapaw Bathhouse was topped with a tiled dome and copper cupola. Here, workers on the scaffolding are tiling the intricate dome pattern. Built on the site of the Horseshoe and Magnesia Bathhouses, this bathhouse was designed by architects Mann and Stern, who also developed the plans for the Fordyce and Ozark.

An integral part of the national park experience has always included enjoying vistas and scenic beauty afforded at mountain overlooks. In Hot Springs, as new roads were completed and automobiles were allowed on the former carriage roads in the mountains, spaces were opened up between trees to enable visitors to stop and admire the surrounding countryside. These vehicles are at the site of the future summit overlook on West Mountain.

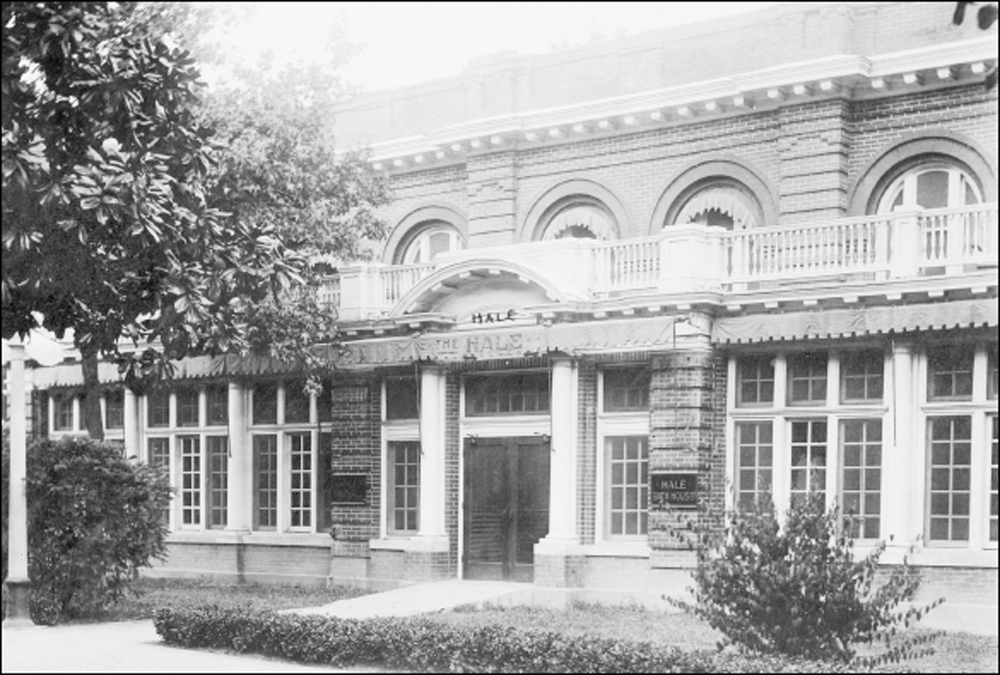

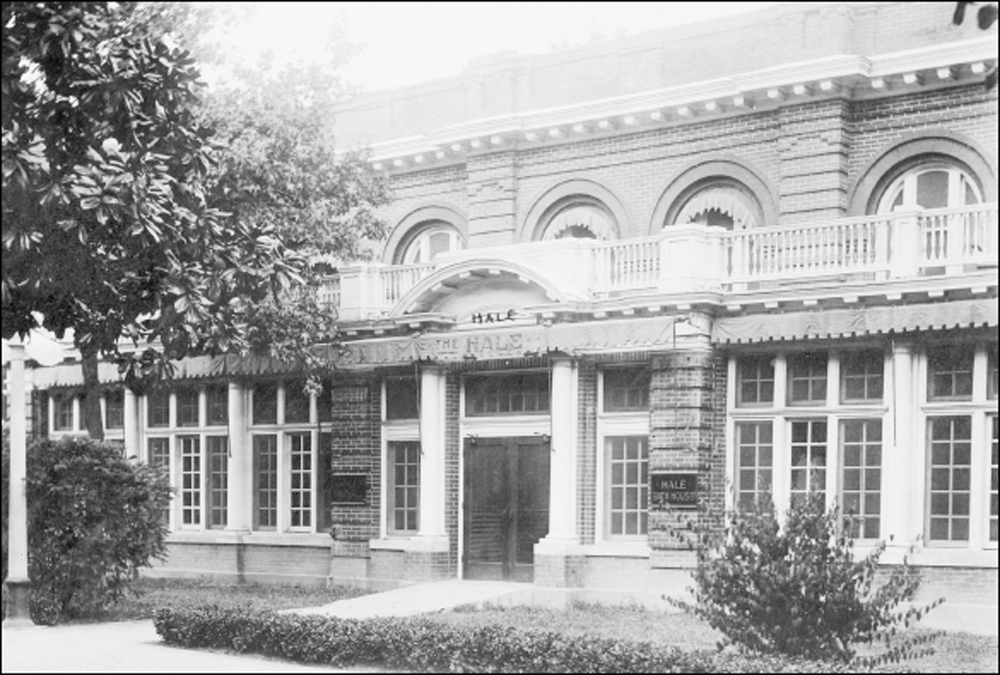

The “new” Hale Bathhouse with a red-brick exterior was built in 1892 and remodeled in 1914, as seen here. As with other bathhouses, the remodel was designed by Little Rock architects Mann and Stern. The redesign enlarged the structure and modified it to resemble the Classical Revival style.

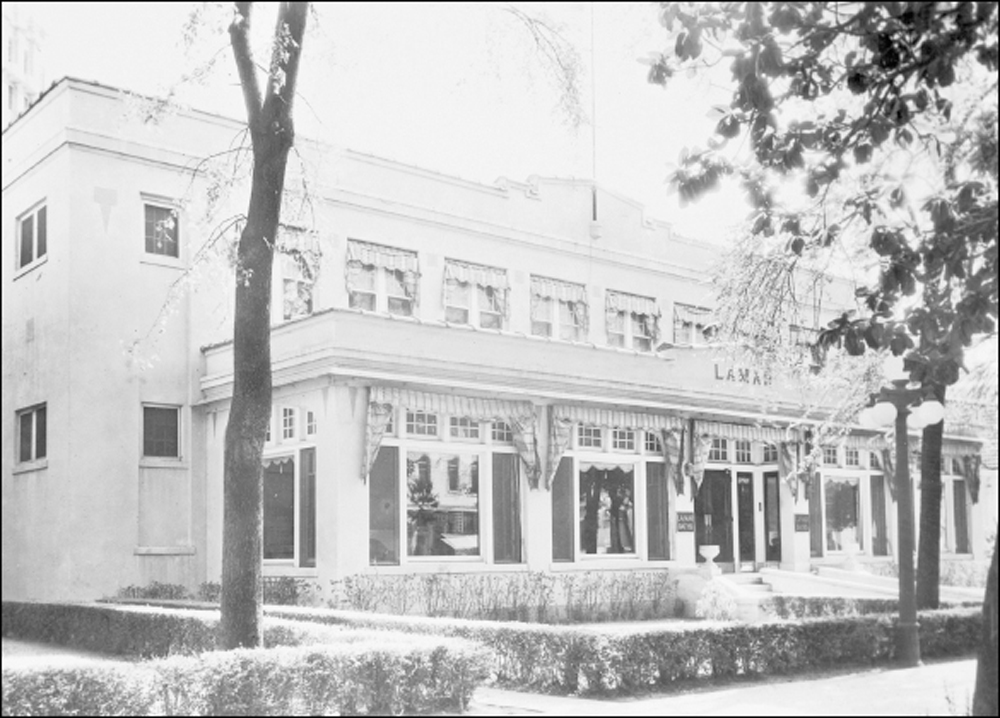

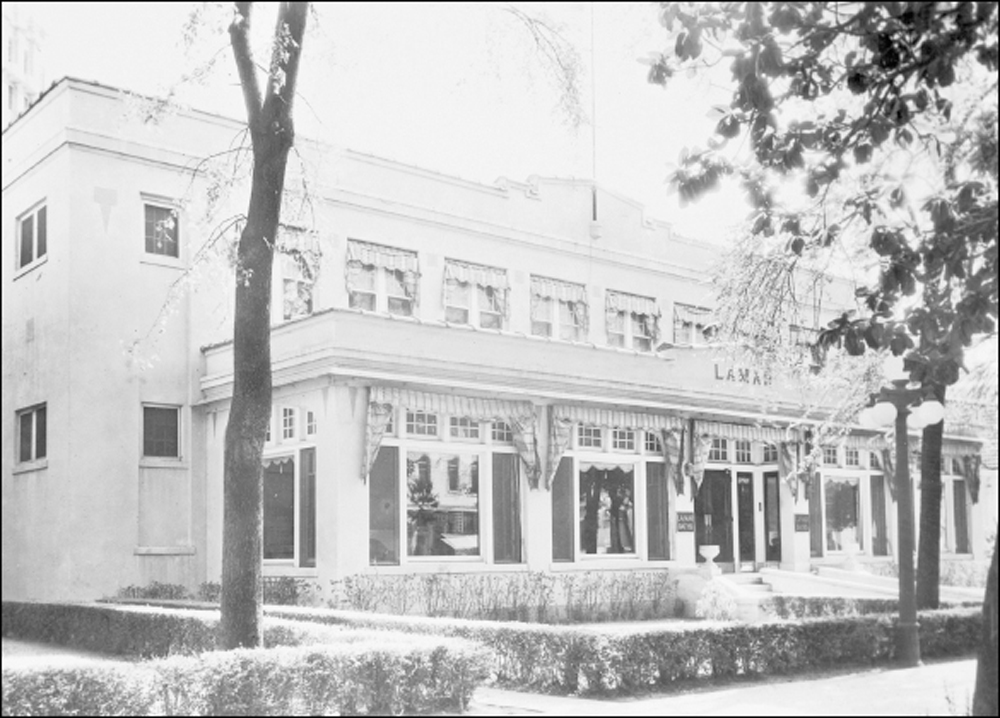

The beautiful Lamar Bathhouse, with its distinctive sun porch, was designed by architects Roberts and Schwebke. The Lamar opened in 1923 and was remodeled in 1931 and again in 1946. Inside, bathers were able to choose from a variety of tub lengths to fit their height, and they could work out in the coed gymnasium.

The lobby of the Lamar is the largest of all eight bathhouses and was used as a lounge for patrons waiting for their therapeutic baths or relaxing after their therapy. In this 1950s photograph, some visitors opt to watch television during their wait. The windows were heavily draped, and awnings were placed over the windows to keep the lobby cool on summer afternoons.

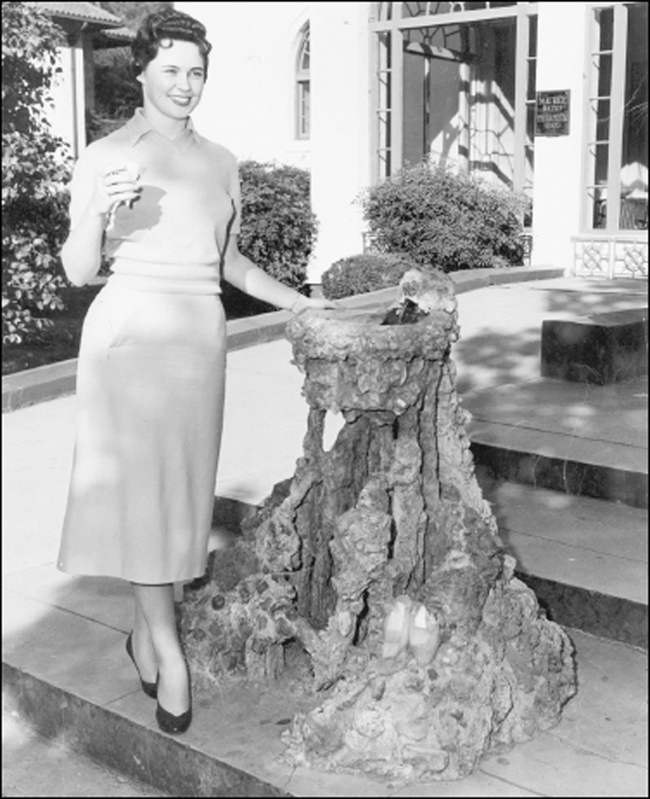

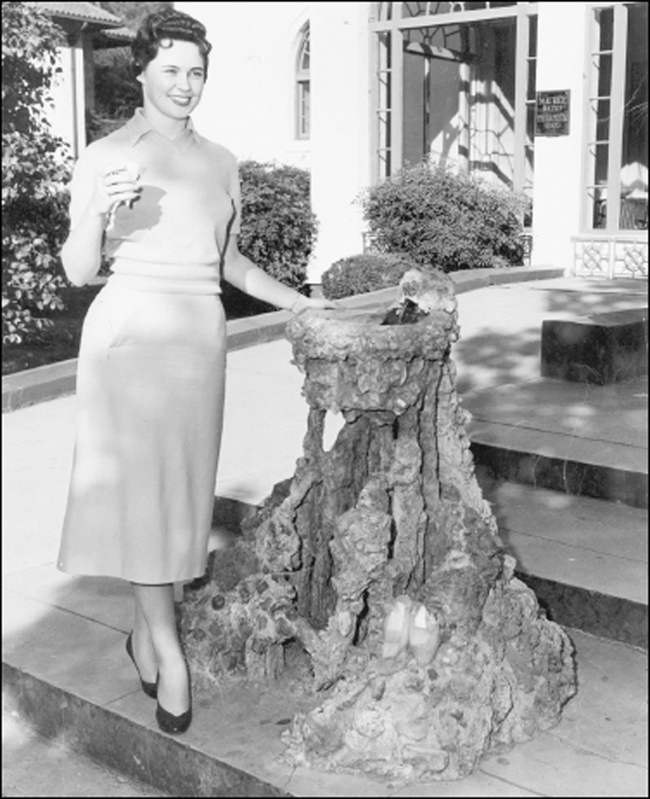

Shelby Bailey, Miss Tennessee of 1956, is drinking thermal water from the Crystal Fountain in front of the Maurice Bathhouse. The unique fountain was installed in 1936, but it was later removed. Composed of tufa rock and concrete with embedded quartz crystals, the unusual drinking fountain was a standard gathering spot for photographs.

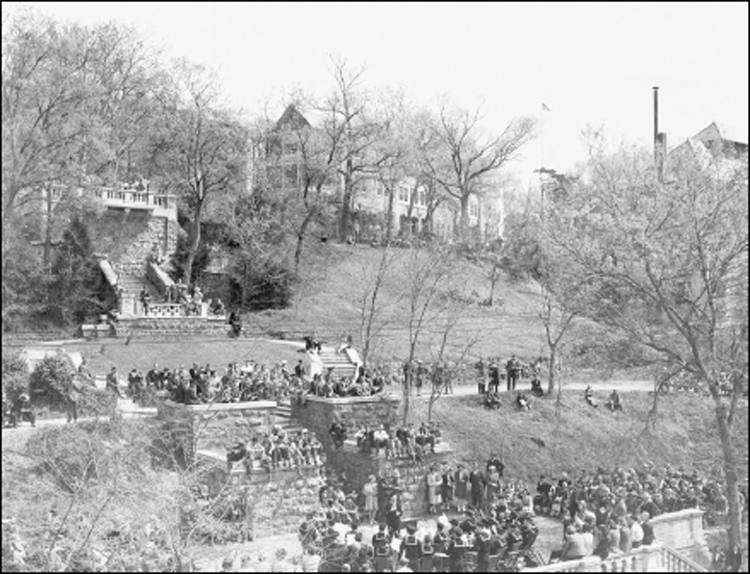

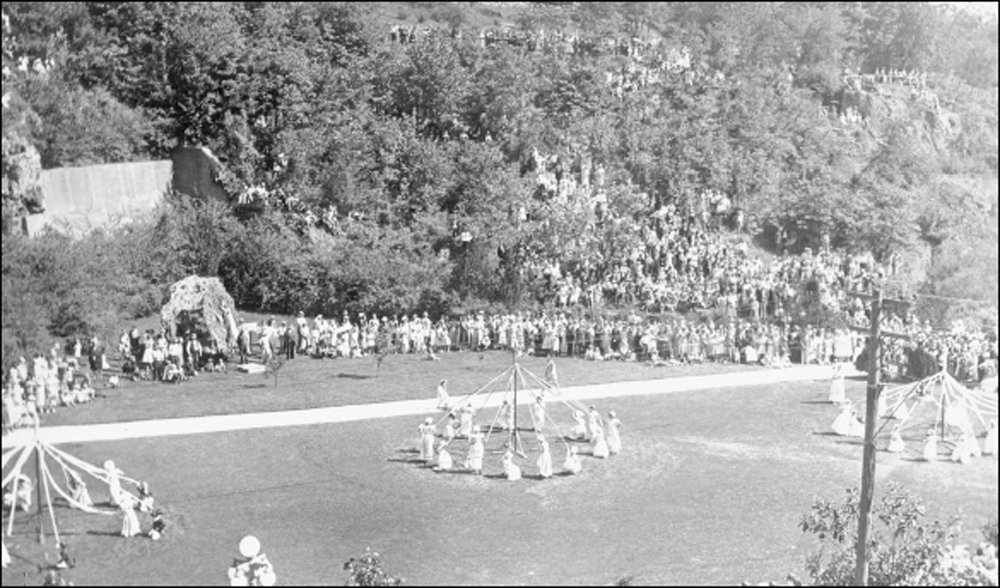

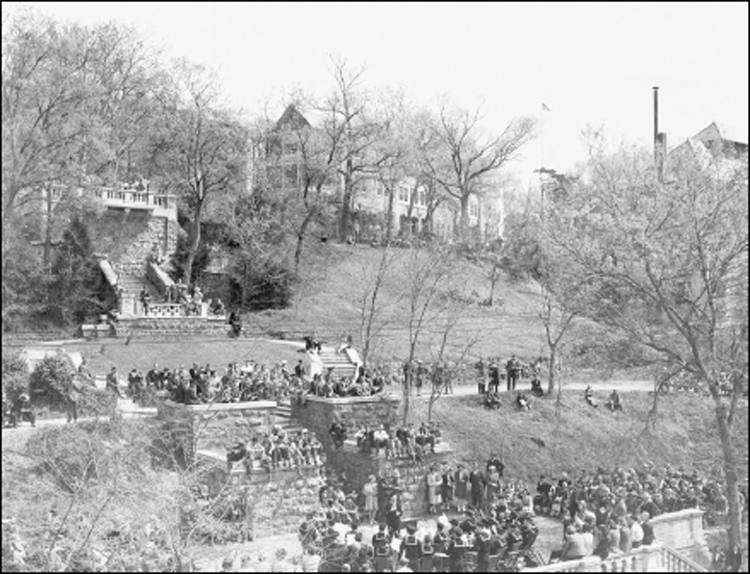

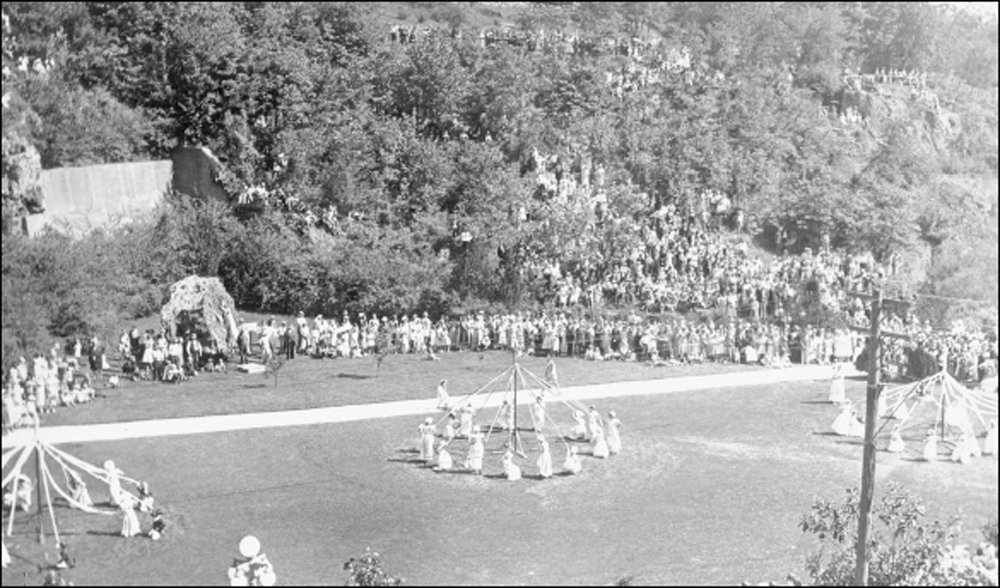

After the Arlington Hotel relocated across the street, the empty lawn space it left behind became the setting for many special events such as the May Day celebration pictured here. Music, dances, and political speeches were often held on Arlington Lawn. During World War II, the area was used for the presentation of military band concerts and medal ceremonies.

Renovations in 1941 at the Ozark Bathhouse changed the overall look of the original 1927 structure by adding wings to each side of the building and enclosing the front porch. At this stage of construction, the south wing has been assembled from brick, but the stucco has not yet been applied to the facade.

This photograph of the Ozark Bathhouse, taken after its exterior face-lift, displays the Spanish Colonial Revival architectural style. Installation of the plaster-cast window boxes and the Tree of Life cartouches on each side of the building added an impression of luxury to the 14,000-Square-foot bathhouse. The Buckstaff Bathhouse is on the far right.

April 1932 was the centennial of Hot Springs Reservation–National Park, and the city turned out to help the park celebrate. History pageants, museum openings, costume balls, and a 30-float parade allowed the people of Hot Springs to demonstrate their pride in their national park and that the city’s springs truly “bathe the world.”

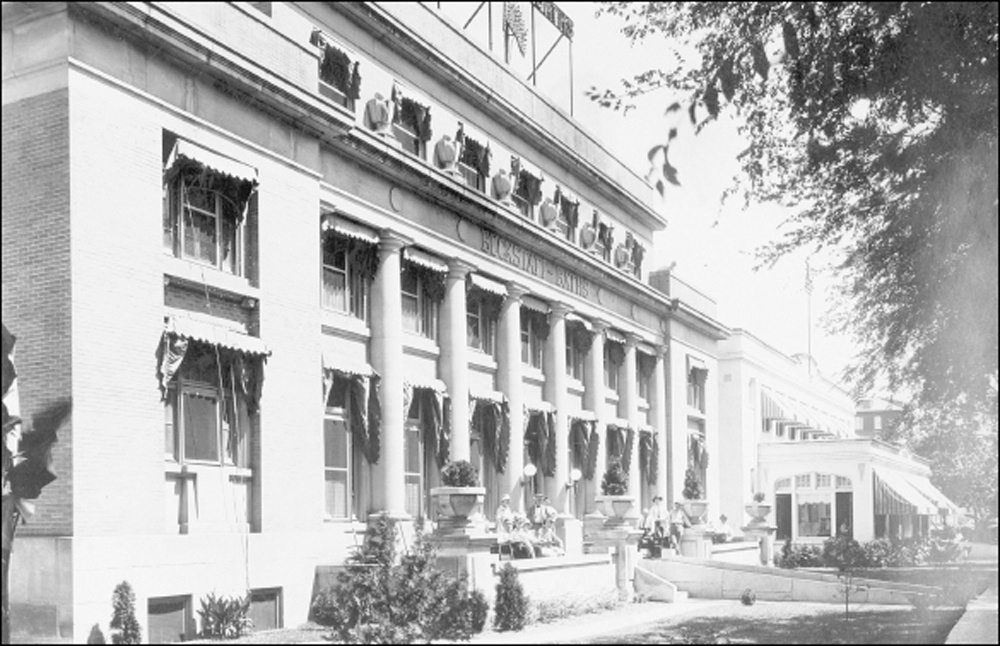

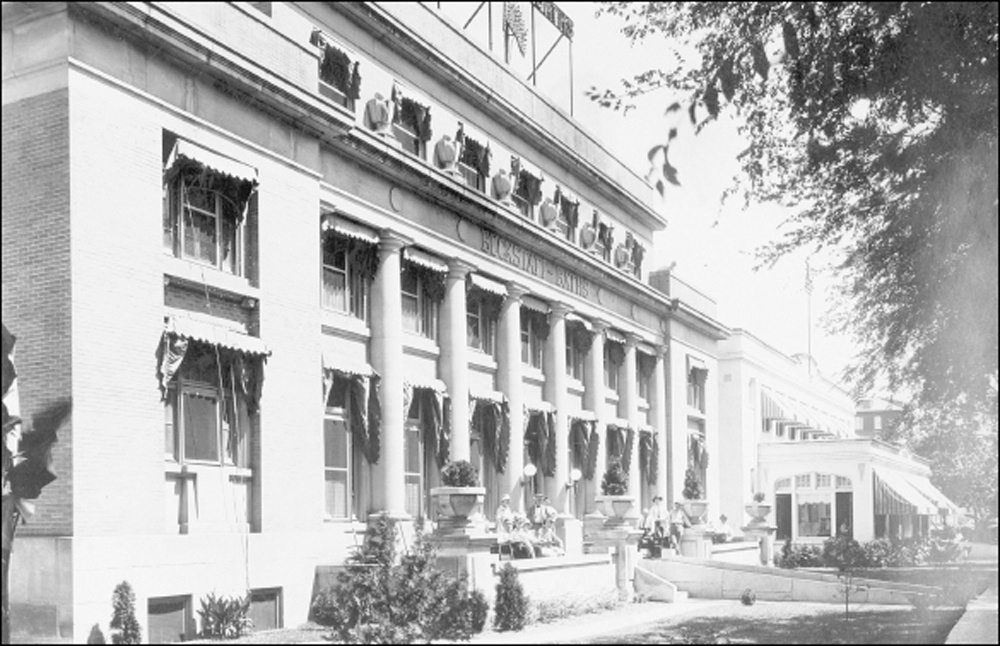

The Buckstaff Bathhouse, designed by Frank W. Gibb and Company in 1912, replaced the Victorian Rammelsberg Bathhouse. Its classic Doric columns reflected the popular Edwardian style of the time. For part of its life, the Buckstaff sported an electric sign on the roof to advertise its location on Bathhouse Row. The Lamar Bathhouse can be seen at the far right.

During the 1930s, the new Administration Building was completed (pictured), the Noble Fountain was moved to its second location away from the street corner, and the Imperial Bathhouse was demolished to prepare for the creation of a more formal south entrance to the Grand Promenade. These and other changes in park landscape and infrastructure were influenced by the National Park Service Landscape Division Design Office in San Francisco.

The Lamar Bathhouse lobby was decorated with European landscape murals, seen on the far wall in this photograph, to evoke the European spa experience. The murals and the ceiling stenciling in the lobby were painted by muralist J.W. Zelm in the 1920s. The Tennessee marble reception counter on the far right was the largest counter in any of the bathhouses.

In this west-facing photograph, taken from the Hot Springs Mountain Observation Tower, the highest point on the horizon is Music Mountain. Hot Springs Mountain is in the foreground, and North Mountain is to the right of the Arlington Hotel downtown. West Mountain extends away from the downtown valley to Music Mountain. All of these areas are part of Hot Springs National Park.

The tiled dome of the Quapaw Bathhouse wears a coating of light snow along the deserted Magnolia Promenade. The roof of the Fordyce is seen left of center. Snow on Bathhouse Row was a rarity, and this dusting may have been an omen of the changing times and attitudes ahead for the bathhouses.