Three

HARD TIMES

The introduction of modern medical technology initiated the precipitous decline of the bathing industry in Hot Springs. People no longer needed to travel to the springs from all over the country for thermal hydrotherapy and associated physical rehabilitation as previously prescribed by their physicians. Breakthroughs in science and medicine created new, more effective treatments that could be administered anywhere. After the zenith of 1947, the bathhouses at Hot Springs National Park began to see their visitation and finances wane.

With the increased availability of the automobile, people no longer had to travel by train. They could go wherever they wanted, and so America began to travel. The war had also exposed soldiers to amazing places and ideas from around the world. Back home, they shared their experiences with their families, who in turn wanted to experience the venues as well. Going to “take the cure” was no longer necessary when medicines were available in one’s hometown. Travel could now be reserved for pleasure, the more exciting and exotic the better.

One by one, the bathhouses began to fall on hard times as business dried up. The first to close was the opulent Fordyce in 1962, and over the next 23 years the bathhouses shuttered their doors and took down their signs until only the Buckstaff Bathhouse remained open for business. The buildings sat empty, and the deterioration that had begun in the last years of operation accelerated at an alarming rate. The heat and humidity in the summer and the cold and rain in the winter silently ate away at the facades. Inside, plaster bubbled and fell from the walls, windows were broken, and time extracted a terrible price on the once-proud sentinels of health. The healing waters could not heal everything.

With business steadily declining, the Ozark Bathhouse closed at the end of October 1977. The addition of massage rooms to the front of the structure during the 1940s renovation, along with a laundry facility in 1958, could not stop the inevitable decline. The building sat empty for the next 29 years.

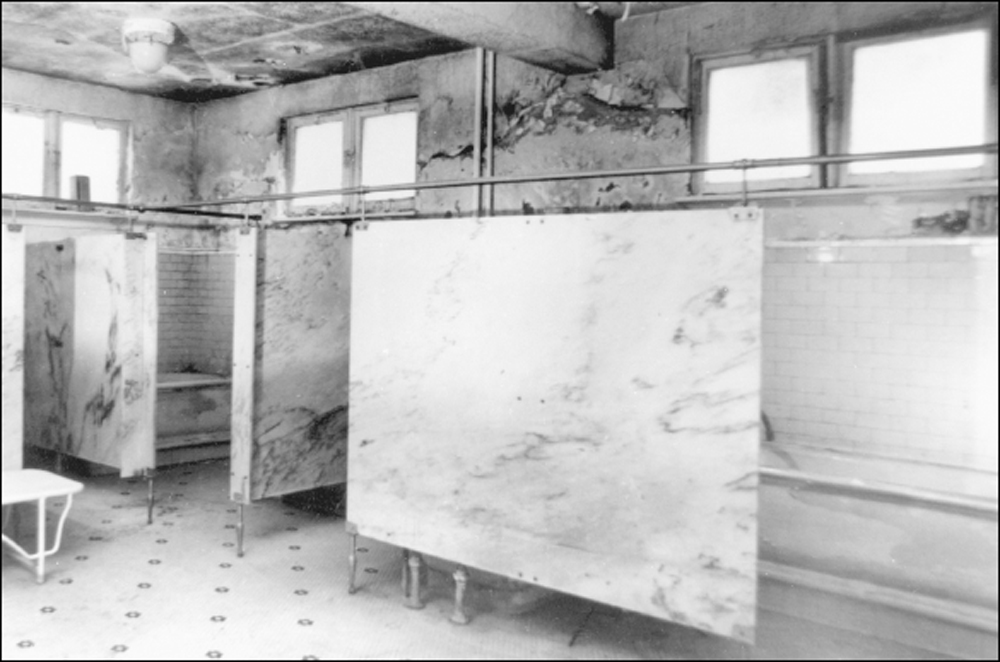

The large men’s bath hall located in the center of the Ozark Bathhouse shows evidence of mold growth along the length of the wall, along with a water leak in the foreground. Many of the bathing stall doors are missing, and plaster from the ceiling and walls has fallen.

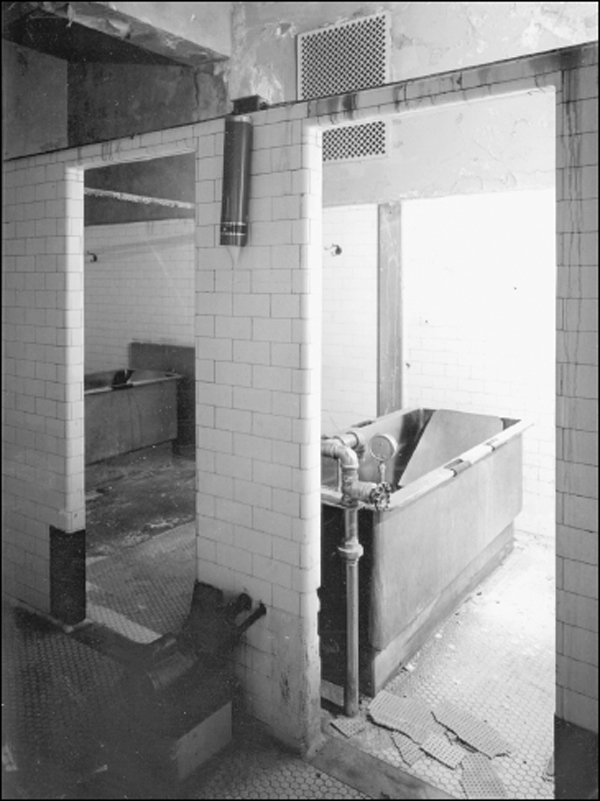

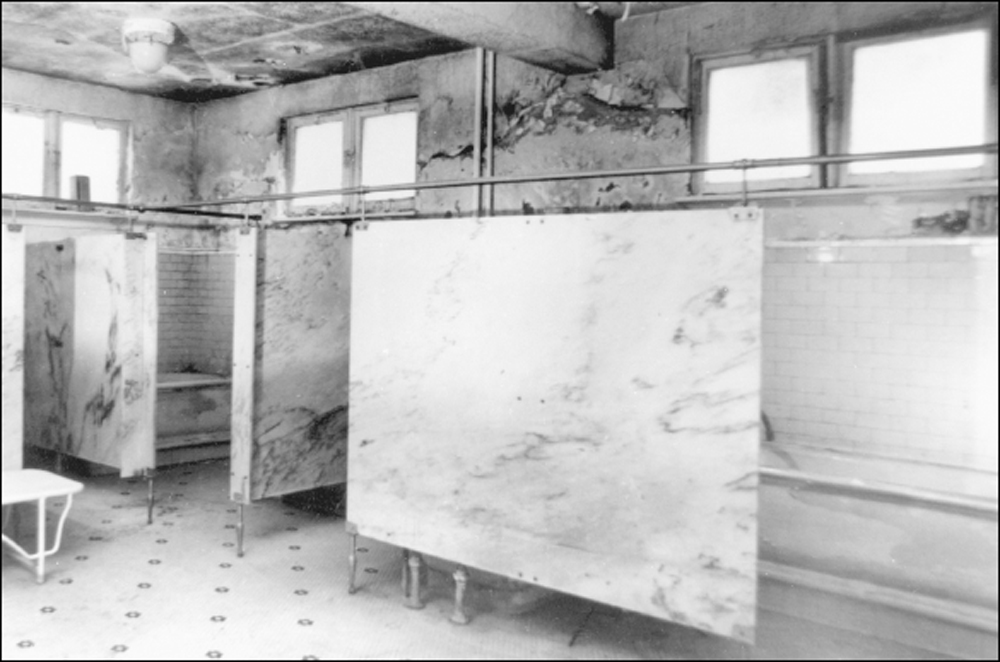

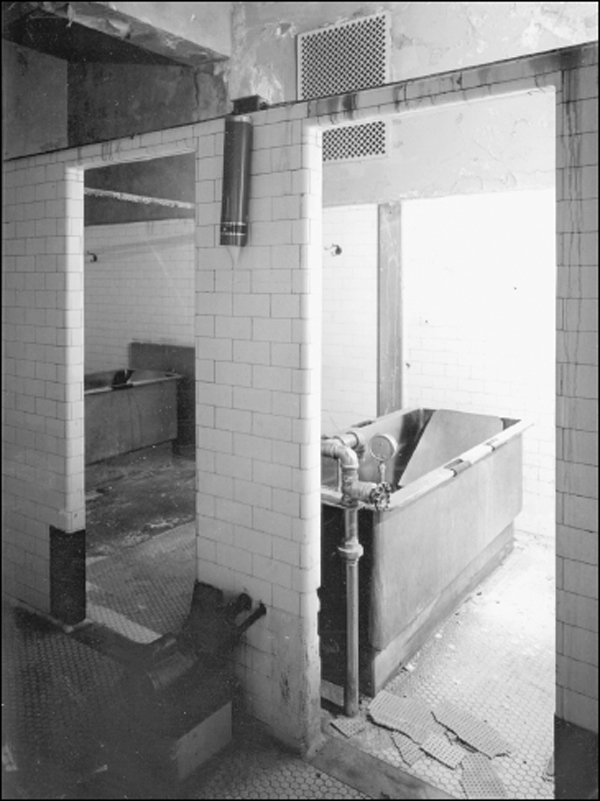

The marble bathing stall walls seem out of place next to the decayed condition of the walls in the Lamar Bathhouse. Extremes in temperature and humidity accelerate the accumulation of moisture and mold, which will grow on plaster surfaces. The white subway tiles on the walls above the tubs are still in good condition.

Stainless-steel whirlpool tubs still have their plumbing fixtures and motors in place at the Quapaw Bathhouse in 1987. This photograph was taken as part of the Historic American Engineering Record (HAER) of historic buildings. Note the paper drinking cups in the dispenser still hanging on the tiled wall.

Even the most elaborate of the bathhouses suffered while closed. The third-floor ladies lounge (later the beauty parlor) in the Fordyce displays extensive damage to the walls in the 1980s photograph seen above. The tile flooring, however, was still in excellent condition. Below, the assembly music room was connected to the ladies parlor through the door at the far end of the room. Its intricate stained-glass ceilings and stenciled walls still reflect the beauty of the original construction despite being heavily damaged by moisture. The large wooden cabinets against the left wall at one time contained John Fordyce’s Native American and Spanish artifact collections.

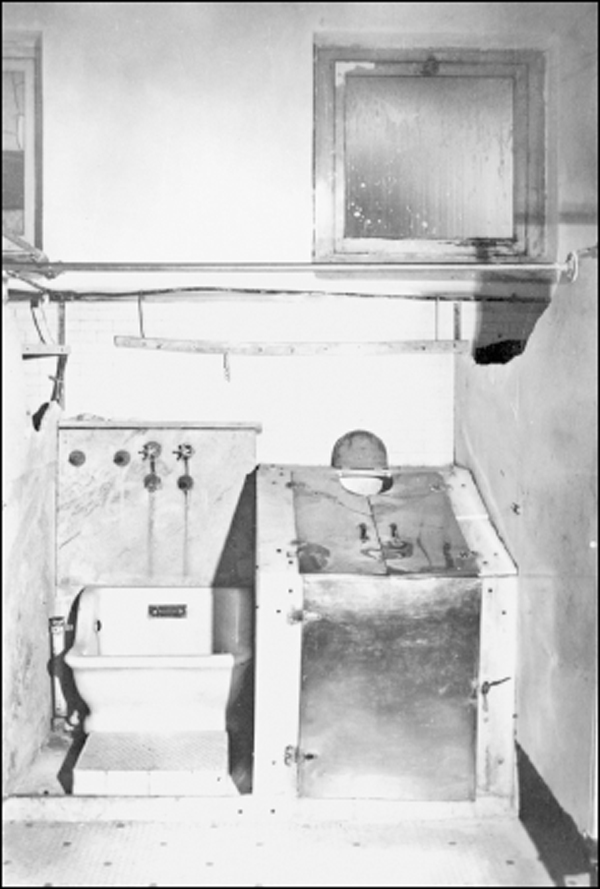

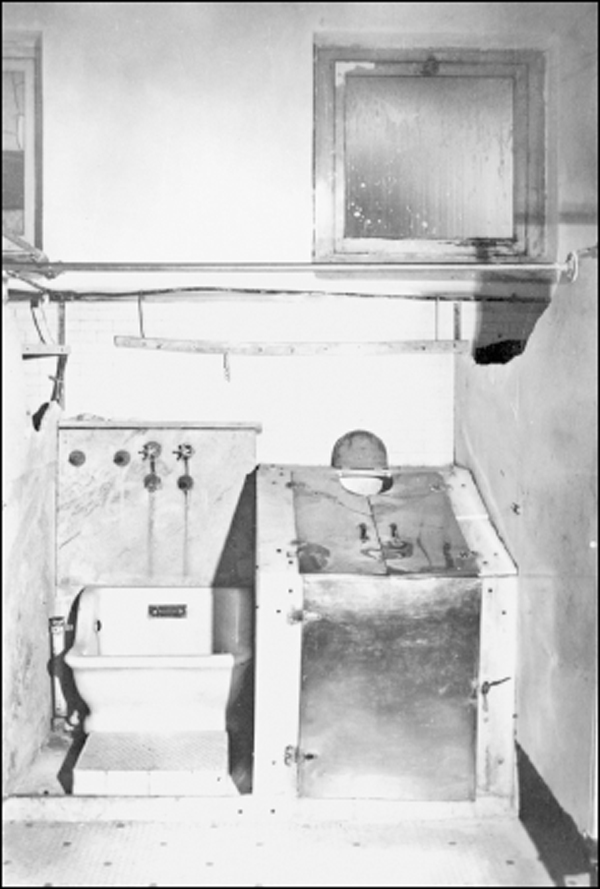

On the first floor of the Fordyce Bathhouse, the men’s steam cabinets and Sitz tub are in a state of disrepair, with parts missing. In 1962, when the bathhouse shut its doors, the rumor was that the building was to be torn down. The building manager instructed staff to remove items they wished to save. Years later, during restoration, former staff members donated original items back to the project.

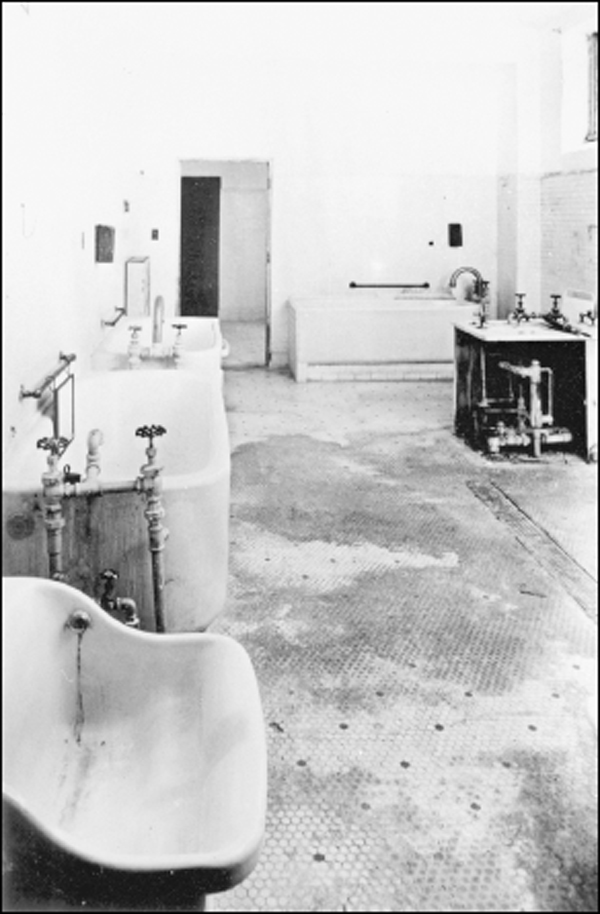

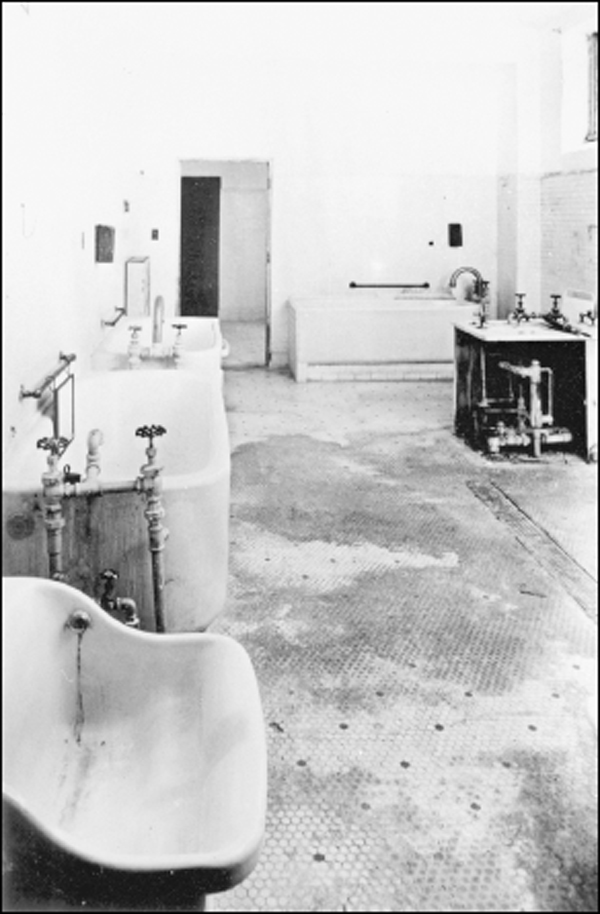

Next door to the men’s steam room, the Fordyce hydrotherapy room once offered a variety of treatments. In this 1980s photograph, the ornate hexagonal tile floor is heavily stained, and major parts are missing from the Scotch douche manifold on the right. The brass handrails along the walls are corroded, and the porcelain tubs are stained with rust.

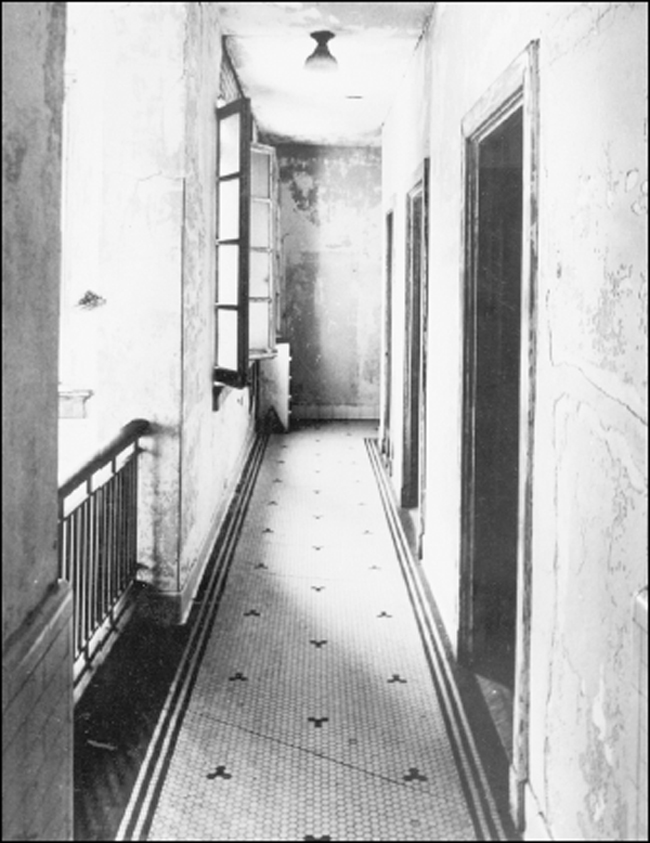

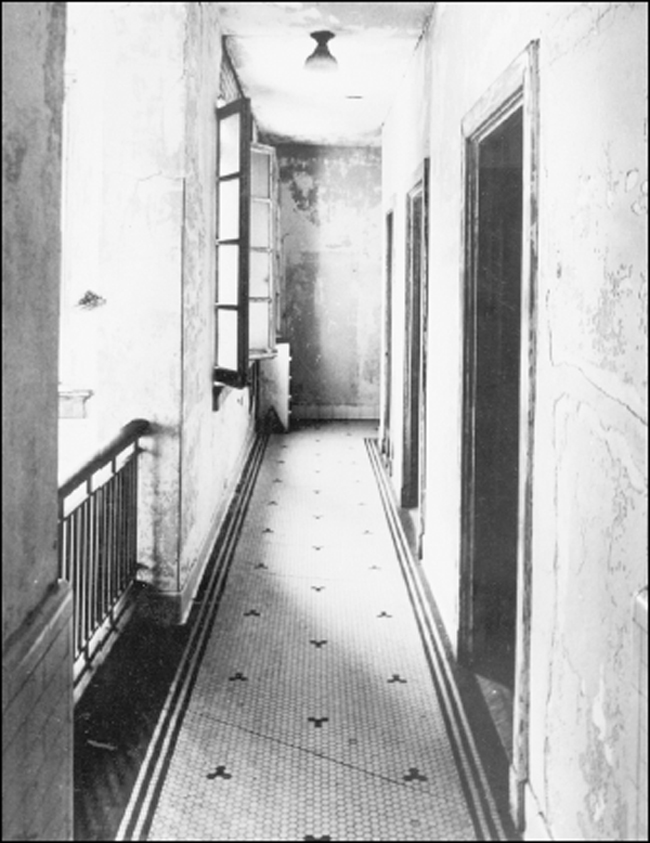

There were no areas of the Fordyce Bathhouse that were not damaged by its long closure. The third-floor hallway on the ladies side of the building (at left) shows peeled and flaking plaster and damaged window frames. Without a working heating and cooling system, the building was at the mercy of the outside elements over the years. A steam cabinet in the ladies first-floor bath hall (below) seems to have survived better than the broken marble stall wall beside it. The window above the cabinet is missing its stained-glass panel, and the frame is decaying. On the far left, the edge of a broken stained-glass window is visible.

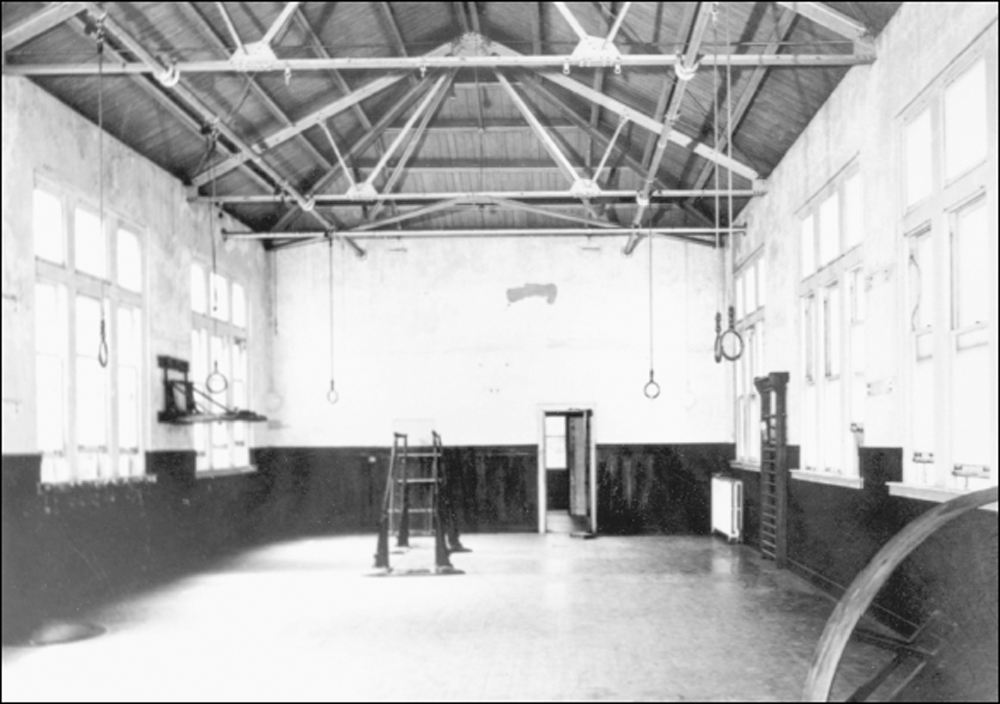

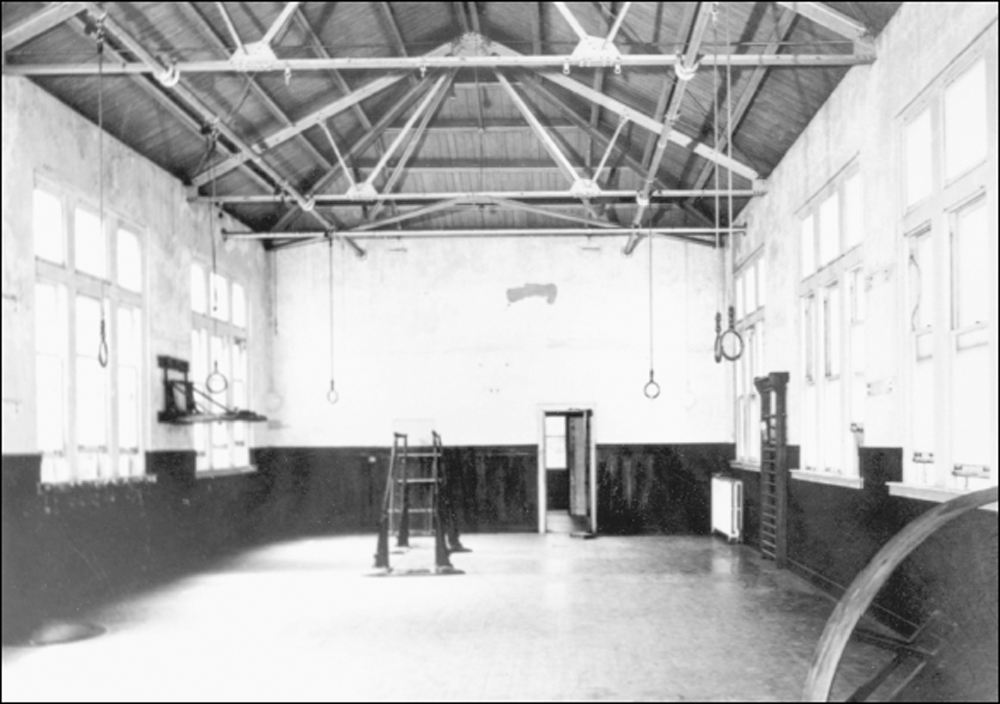

Once a hive of therapeutic activity and wellness, the gymnasium on the third floor of the Fordyce here shows the effects of years of neglect. Mold is undermining the plaster on the upper walls and the wooden ceiling. A pool of water is visible on the right side of the room near the white radiator, indicating a roof or window leak.

The last person to live in the Medical Director’s Residence on Reserve Street was park superintendent Richard Maeder. He moved out of the house in 1978, and it remained empty for over 20 years. In this 1990s photograph, vines are taking over the structure, which at that time was being used for storage.

Ending its operation in 1974, the elegant Maurice Bathhouse had altered its exterior appearance very little since the renovation of 1915. In keeping with Hot Springs National Park custom, the unoccupied building is not flying the US flag on its flagpole, as shown in this 1990s photograph.

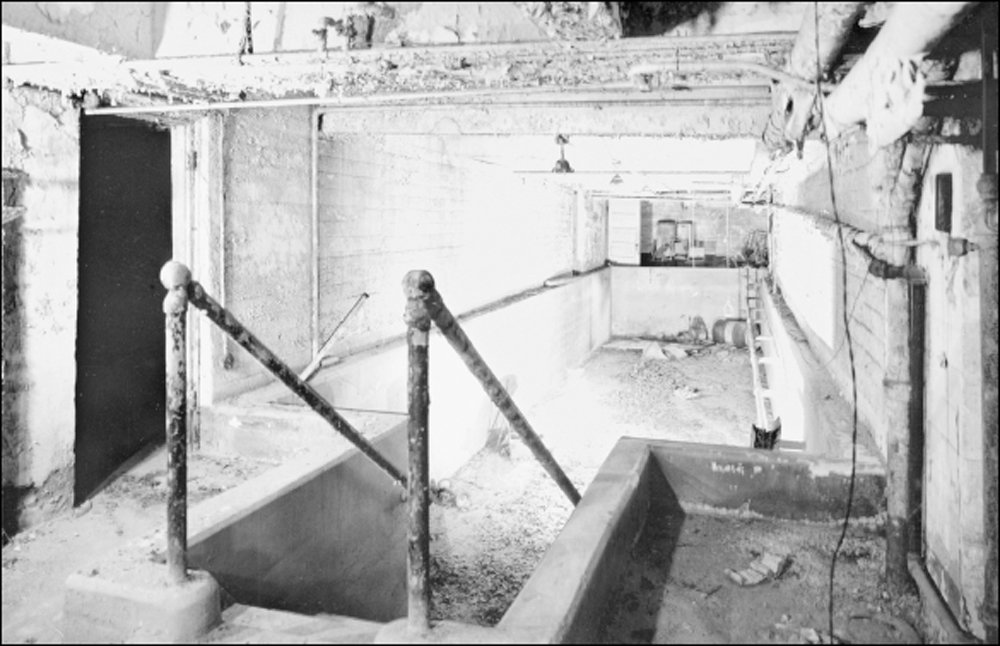

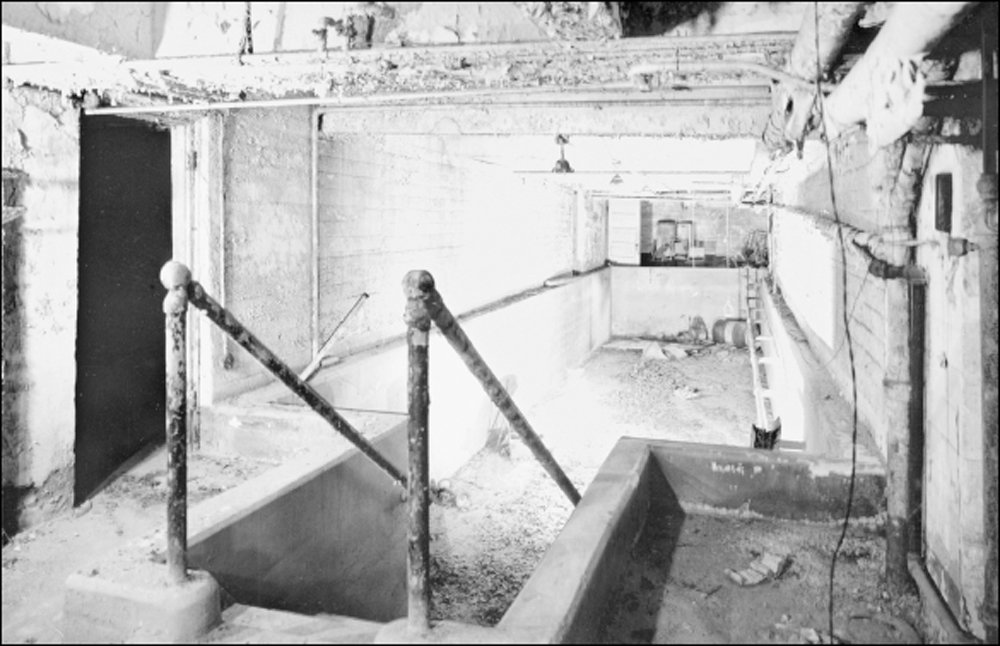

Once an inviting oasis and a technological innovation on Bathhouse Row, the therapeutic pool in the basement of the Maurice fell into disrepair after the closing of the building. The pool, added in 1931, was the largest thermal pool available on Bathhouse Row. The damages suffered by all the bathhouses over time would prove challenging to National Park Service conservators and restoration workers in the coming years.