Four

A NEW LEASE ON LIFE

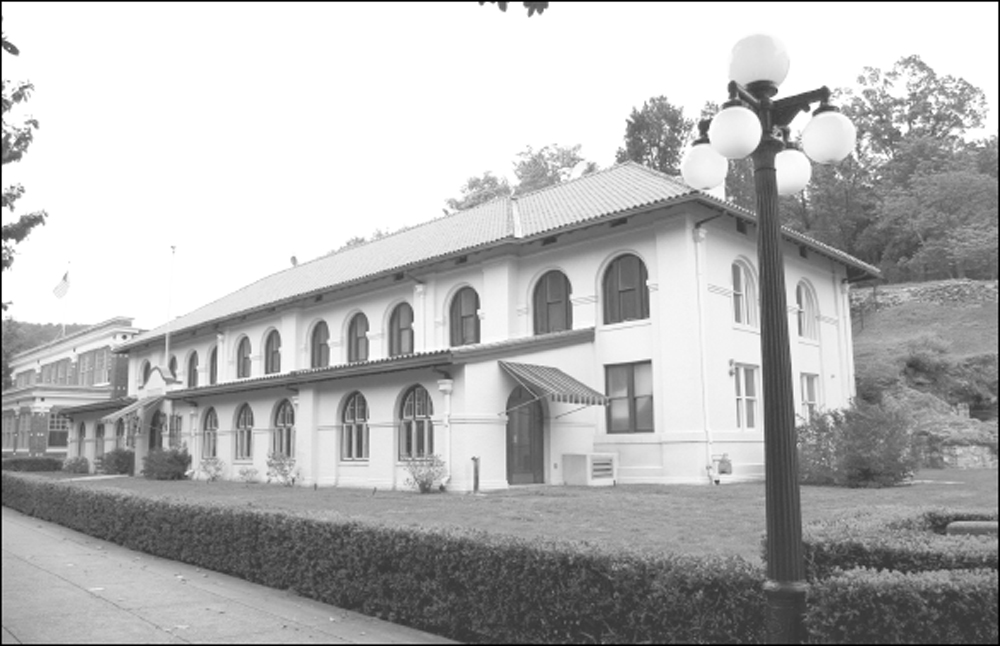

Recognition of the historical significance of the bathhouses helped save them from ruin. Beginning with their listing in 1974 in the National Register of Historic Places, the National Park Service worked to obtain funding to protect the buildings from further deterioration and made plans on how to move ahead. Although plans to restore the structures would not be reminiscent of the formal gardens and other aspects of Mann and Stern’s design from 1917, the renovation of the buildings would bring them back to the early 1900s, when they were at their pinnacle of architectural beauty.

Changes were not only happening with the bathhouses, but in other areas of the park as well. The Grand Promenade was always a wonderful pedestrian pathway for visitors to enjoy, and it was no surprise when it was designated a National Recreational Trail in 1982. It was also selected to be part of the National Historic Landmark District in 1987, along with Bathhouse Row and the formal entrance to the park.

Adaptive reuse of the buildings would be the key idea that would mean new opportunities for the bathhouses in the future. The park no longer looked at them as simply bathhouses; they would be open to other business ventures through leases and concessions that would protect the historical integrity of the buildings and bring services to park visitors.

In 1957, the park hosted a planning conference for the Park Service’s Mission 66 improvement program. The Mission 66 program provided for a multitude of developments park-wide, including landscaping enhancements along the Grand Promenade. Here, park gardeners and foresters plant new trees just behind the Quapaw Bathhouse near the site of the old Government Free Bathhouse.

The 300-seat amphitheater at Gulpha Gorge Campground was part of the Mission 66 improvements to the park. It was completed in November 1965, along with a new entrance road for the campground. The new amphitheater had a rear-projection screen and a sound system for multimedia shows and ranger-led programs.

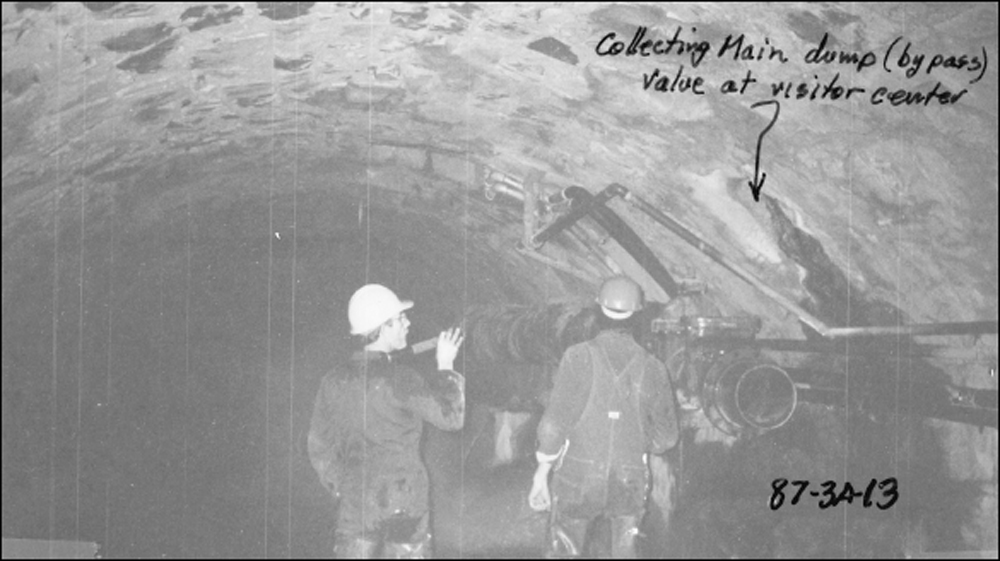

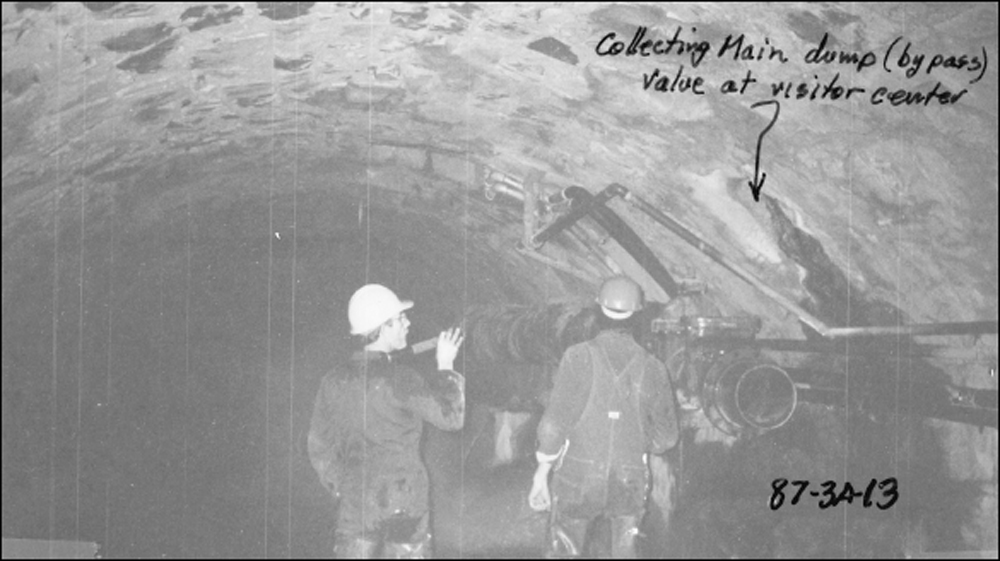

An engineering inspection of the Hot Springs Creek arch beneath the lawns of Bathhouse Row was completed in 1987. In this view, the thermal water-collecting pipe is visible, suspended from the wall of the arch. Originally, this iron pipe was insulated with redwood boards held together with tar to sustain the heat from the thermal waters as they were piped to holding reservoirs.

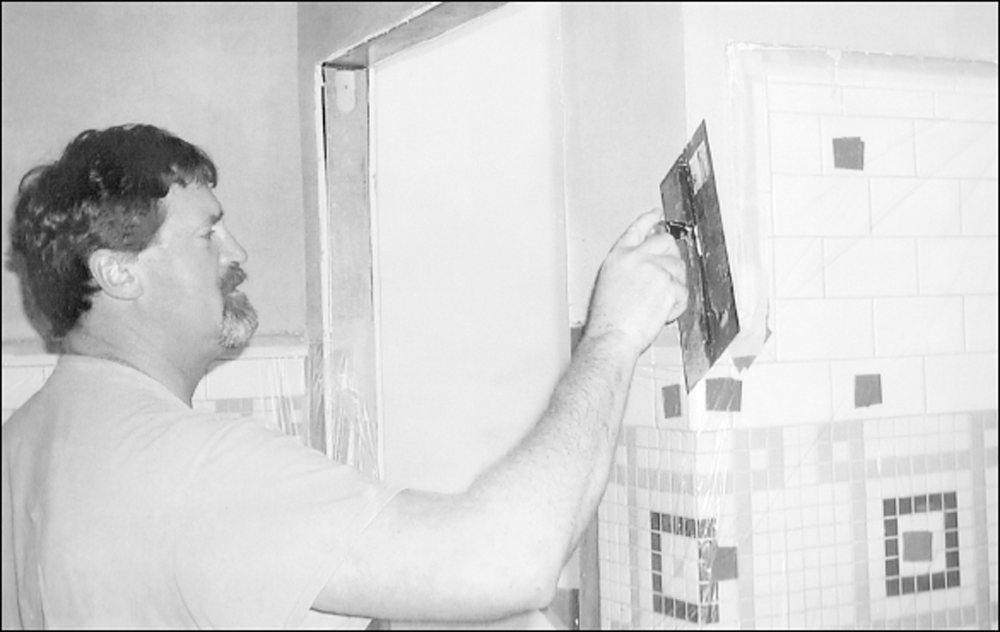

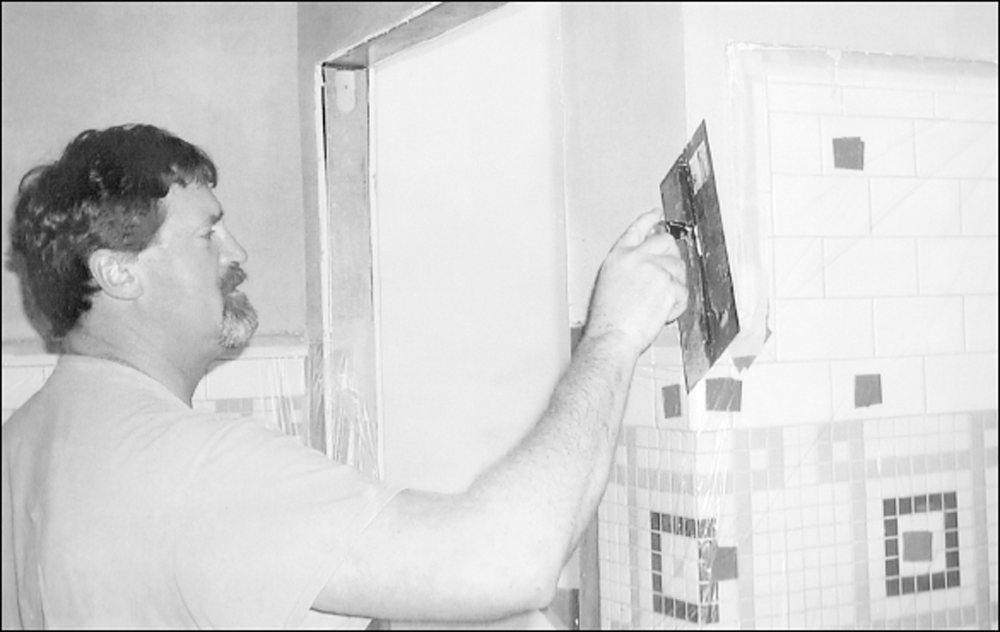

Park maintenance technician Mel Hayes was one of many restoration specialists called on to help bring the bathhouses back to life. Here, he is replacing the glass in a window sash for reinstallation. The preservation team removed lead paint, asbestos, and other harmful substances in preparation for adaptive reuse of the buildings.

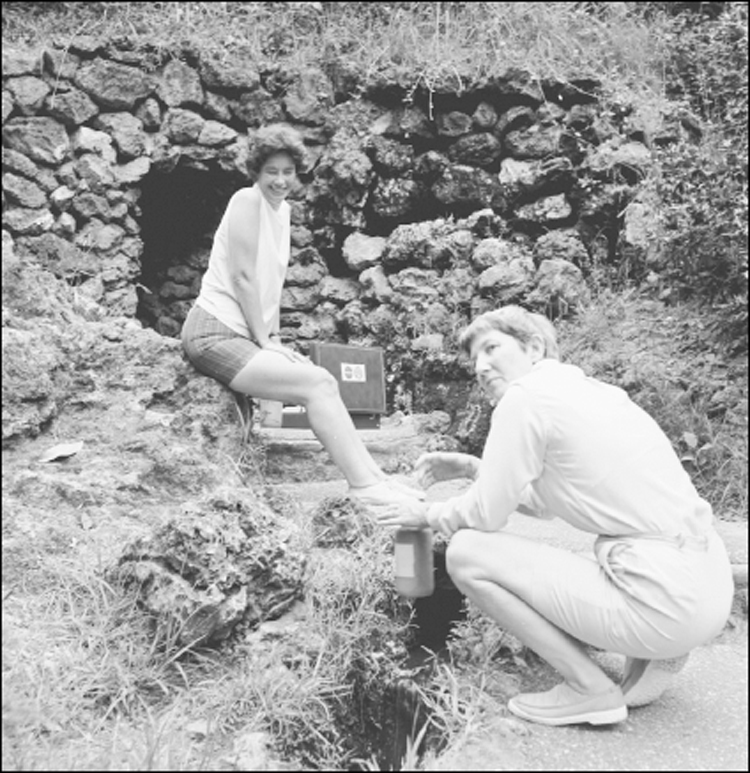

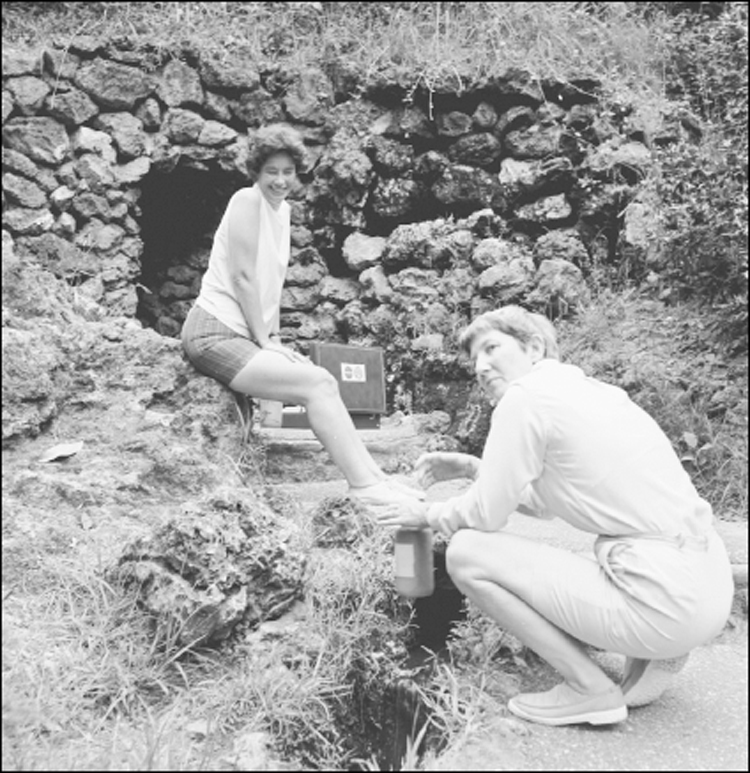

Scientific research was reemphasized in the park beginning in the 1990s. Helen Lacy (left) and Sally Burtram from the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) in Houston are gathering thermal water samples to be used in a NASA program. Their research on the hot water taken from the Display Springs behind the Fordyce and Maurice Bathhouses detected a tiny microbe in the waters.

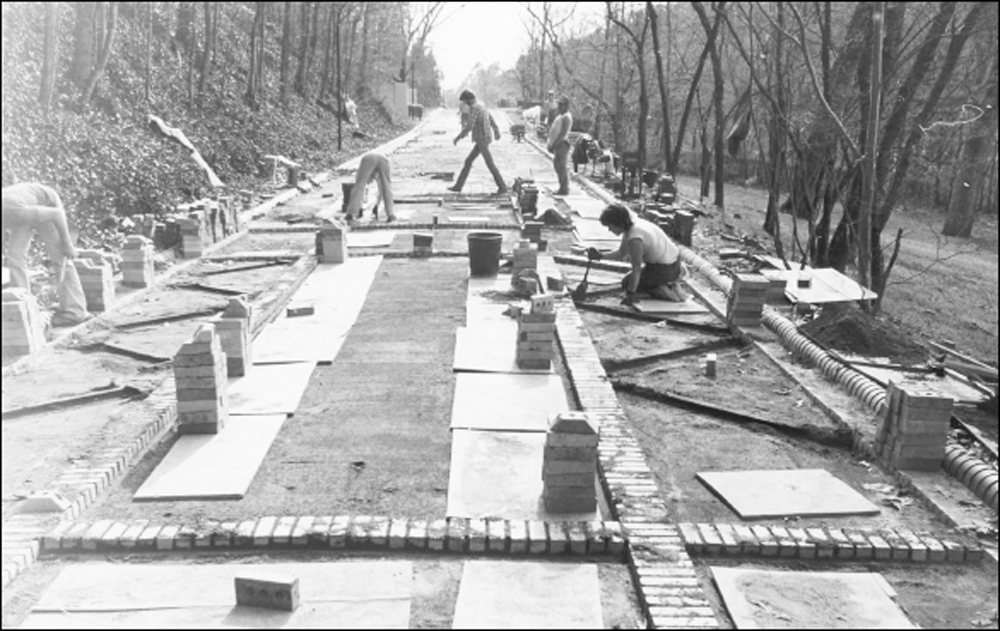

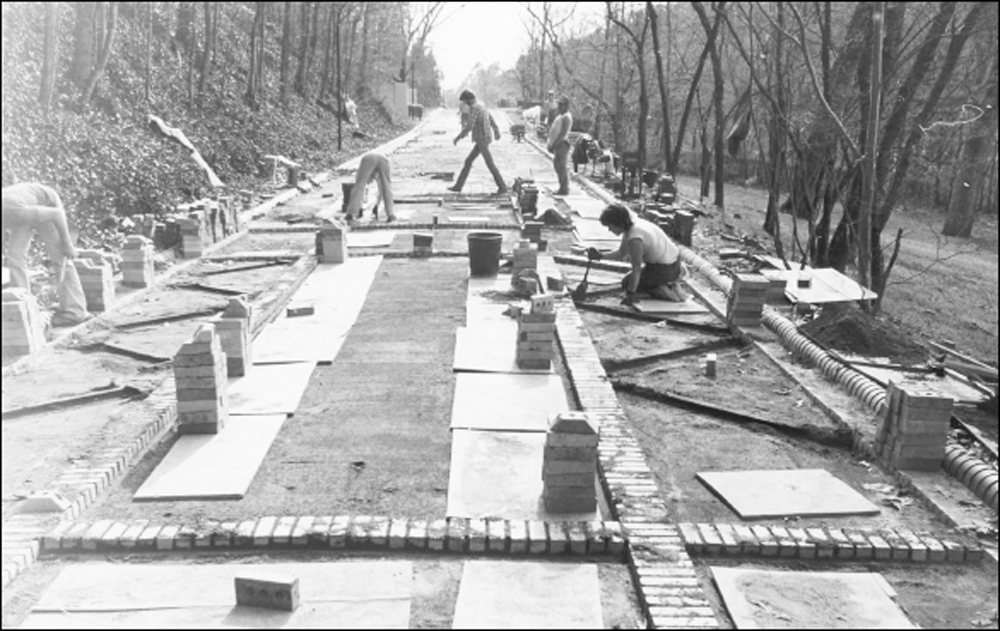

The Grand Promenade began as a Public Works Administration project in the 1930s, although there were walking trails along the hillside before the brick walkway was installed. In 1982, the brick and sand promenade was designated a National Recreation Trail. In 1984, the park worked to reconstruct the intricate paving pattern by replacing the sand substrate with cement.

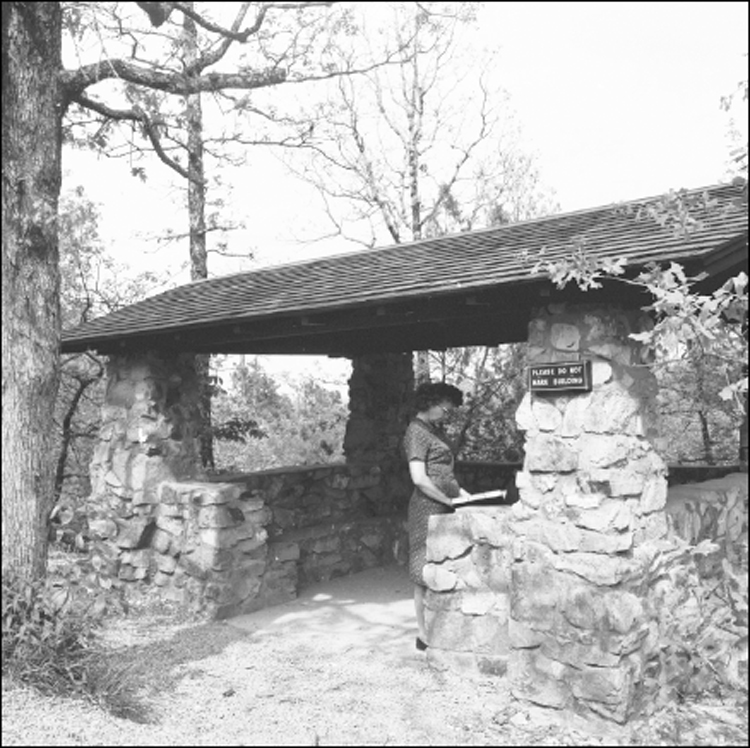

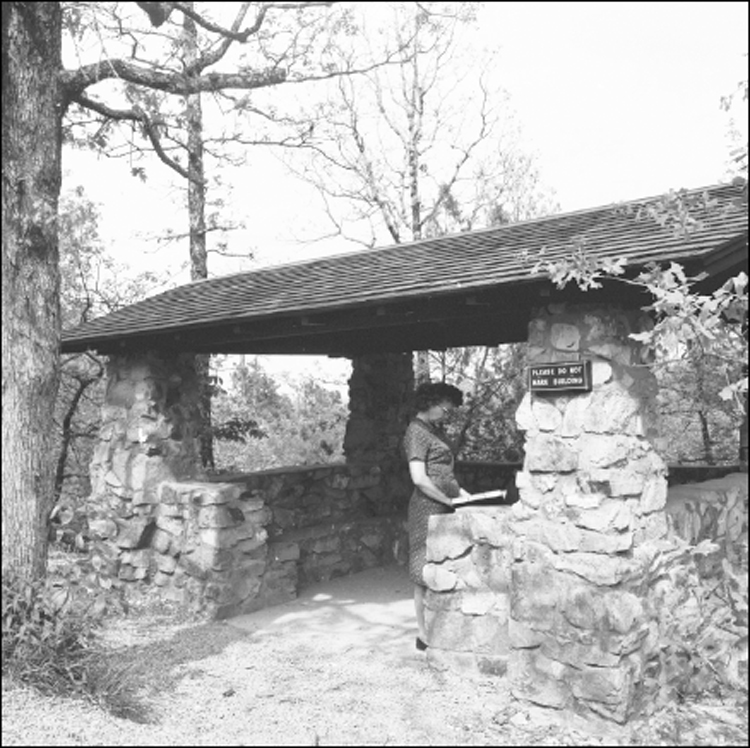

Stone shelter houses along the mountain trails provide a welcome respite for hikers throughout the park. This North Mountain shelter also features a wayside exhibit on the flora and fauna of the park. A sign to the right warns would-be graffiti artists not to use the building as a canvas.

Looking northeast from an overlook on North Mountain, a park ranger describes to a group of visitors the topography of the Zig Zag Mountains. The area they are surveying is known today as the recharge zone for the thermal springs. Recent research has shown that the thermal water discharging today from the springs fell as rain here while the pyramids of Egypt were under construction more than 4,000 years ago.

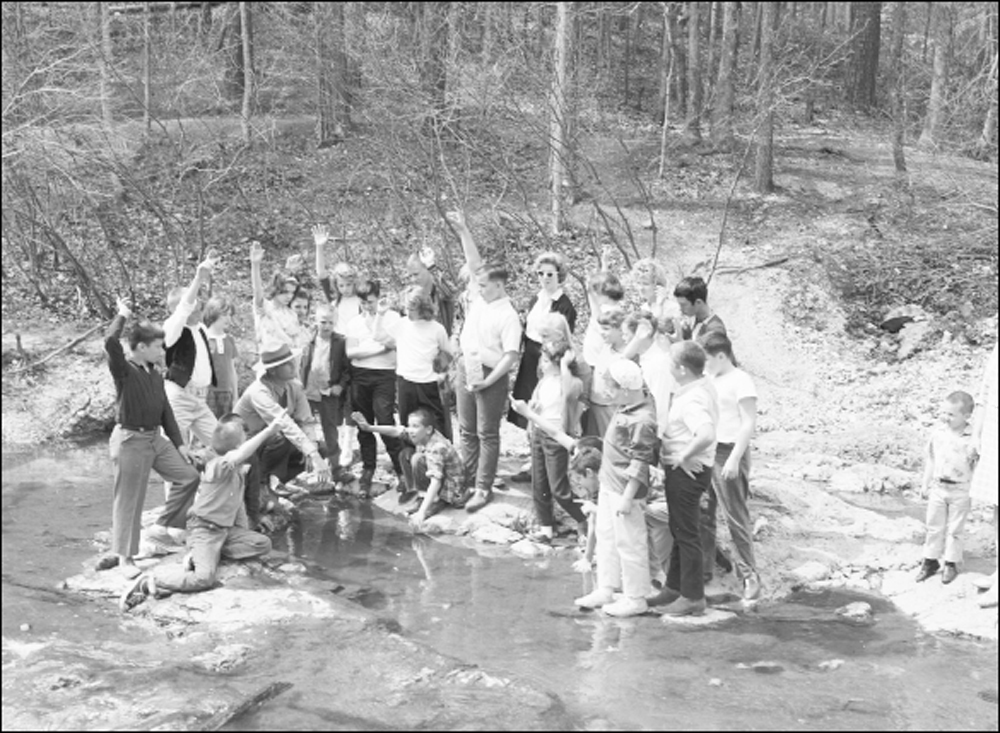

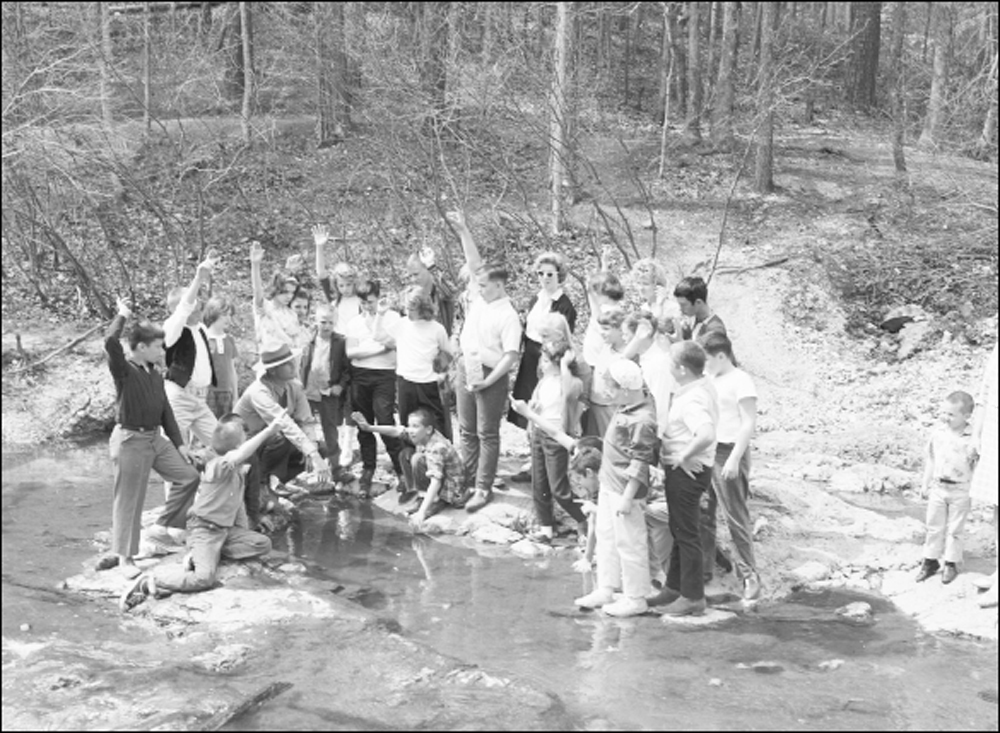

A park ranger leads an interpretive hike along Gulpha Creek near the campground. School tours allow students to be introduced to the intricacies of the national parks and the world around them. Interaction between children and interpreters teaches young people the importance of being future stewards for the environment.

This is the latest version of the Observation Tower at the summit of Hot Springs Mountain. It was completed in 1983 and rises 216 feet in the air, providing a view of the park and the surrounding Ouachita Mountains. Visitors can ride a glass elevator to the top to enjoy the scenic beauty from multiple decks.

Restoration specialist Michael Powell re-plasters the walls of the Ozark Bathhouse during the building’s renovation. For several years, the park employed a well-trained team of craftspeople who painstakingly removed lead paint and asbestos, replaced wiring, installed new air-conditioning systems, and repaired tile and plaster throughout each bathhouse. Slowly, the buildings were restored to life.

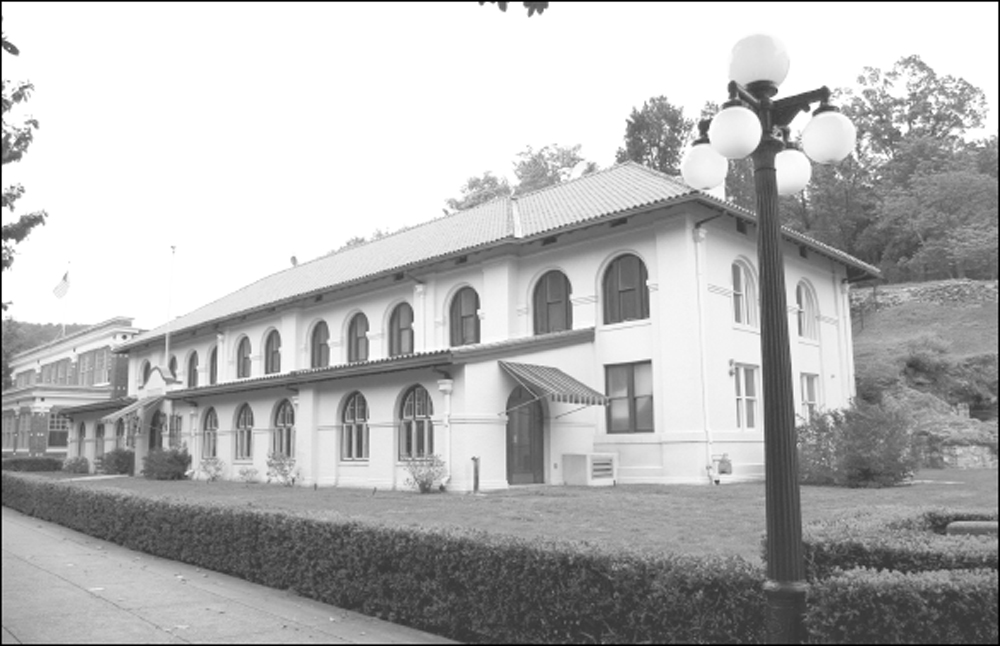

Restoration of the Medical Director’s Residence at the intersection of Reserve and Spring Streets was completed in 2005. Today, it is home to the US Department of Agriculture Forest Service Southern Research Station, where scientists study southern pine ecology and manage upland forest ecosystems in the mid-South. (Author’s collection.)

The Lamar Bathhouse is now the home of the park store, the Bathhouse Row Emporium, operated by Eastern National. The shop, which opened in 2012, sells a variety of health and wellness-related items, as well as usual national park gifts. The building also houses park staff offices and museum collection storage spaces. (Author’s collection.)

Still in operation after over a century, the Buckstaff Bathhouse continues to provide the traditional-style thermal bathing experience for its patrons. The men’s bathing department is located on the first floor, and the ladies’ area is on the second floor. The staff also offers massage therapy as part of their bathing regimes. (Author’s collection.)

Since early 2014, the Ozark Bathhouse has been the home of the park’s cultural center, operated by the supporting organization Friends of Hot Springs National Park. Its galleries host special events and traveling exhibits, as well as the park’s entire artist-in-residence art collection. Previously, the building was home to the Museum of Contemporary Art. (Author’s collection.)

The Fordyce was restored to be the park’s museum and visitor center, opening to great fanfare in 1989. It hosts more than a quarter of a million visitors per year. The museum is configured as the Fordyce was when it opened in 1915, with historic artifacts, furniture, and other museum objects on exhibit. (Author’s collection.)

The only bathhouse on the row that has not been completely renovated, the empty Maurice has been re-roofed and its foundation stabilized to protect the building for the future. The restoration of its ornate lobby was begun and mostly completed, but work remains. Other areas in the facility are cleared out in anticipation of future leasing proposals. The lobby is periodically used to host special events. (Author’s collection.)

Like the Buckstaff, the remodeled and updated Quapaw is today operated as a working bathhouse and spa. Instead of the traditional baths, the Quapaw provides communal bathing in four large soaking pools and a private bathing area for individuals. A café and boutique round out the amenities offered to bathers. (Author’s collection.)

The Hale Bathhouse had been restored and stabilized for adaptive reuse, and over the last few years it has housed a variety of short-term leases, such as gift shops and other retail operations. Requests for proposals are periodically released by the National Park Service to allow organizations to suggest how best to use the building. (Author’s collection.)

The Superior reopened in early 2013 as the Superior Bathhouse Brewery and Distillery, operated by Vapor Valley Spirits, Inc. The craft brewery uses thermal springwater to create its products and also makes its own root beer and Italian-style gelato. A full restaurant menu is offered at lunch and dinner. The business hosts special events, receptions, private meetings, and parties on the second floor. (Author’s collection.)

Whittington Park is now a peaceful retreat for walkers, joggers, and visitors who want a quiet place to rest. Whittington Creek slowly meanders through the landscape within a stone-lined pathway. Summer band concerts are held in the park to commemorate the Fourth of July and other special events. (Author’s collection.)

The fire ring and amphitheater at Gulpha Gorge Campground are the sites of summer campfire talks given by the interpretive rangers at the park. The lush picnic grounds and cooling waters of Gulpha Creek are still an enticing summer destination for both local and out-of-state visitors. (Author’s collection.)