“Action without understanding only leads you back to darkness.”

– B. Bryan Post

In each section to follow, you will find a definition of the problem behavior and then a perspective on each behavior from what we call the “Traditional View” and “A New View.” As you read the new view perspective, it is important to keep in mind four key principles that create the foundation for the understanding and techniques being offered. The full understanding of the four principles will enable you to understand and be aligned with chapters that follow. It is our goal that these four principles empower you as a parent to feel equipped to apply the understanding and techniques to help your child with any behavior he presents to you.

Our belief is that many of the things we do are based on and driven by our understanding. The things we do are not done to be mean or intentionally cruel, but are done from the perception and understanding within us. Our actions are directed, guided, and aligned with the core principles within our understanding. Everything we do can ultimately be traced back to the guiding principles from which we operate. Thus, it is imperative that you read and reread this section as often as possible to fully comprehend the new perspective.

So read, and then reread this chapter on the Stress Model before you attempt to fully delve into your understanding of the behaviors – before reading the following seven chapters.

The New View that will be discussed in this book is based on four key principles. First, all negative behavior arises from an unconscious, fear-based state of stress. Second, there are only two primary emotions, love and fear. Third, there is both negative and positive repetitious conditioning. We are all conditioned to behave in various ways, both good and bad. And fourth, negative and positive neurophysiologic feedback loops exist beyond our conscious awareness. They occur at an unconscious physiologic level and we have the ability to change or add to these feedback loops. Let’s take each principle and break it down.

PRINCIPLE #1

All negative behavior arises from an unconscious, fear-based state of stress.

It was once said to me, “Scared children do scary things.” The simple truth in this wise statement is that while we believe that children are perfectly capable of making clear and rational decisions, we also need to believe the opposite – that children are incapable of making clear and rational decisions. In fact, stress research helps us to understand just that. In times of stress, our thinking processes become confused and distorted.1 Not only are we not thinking clearly when stressed, but the very framework of our understanding is challenged in that moment by what we can believe and remember. For not only does our thinking become confused and distorted, our short-term memory system becomes suppressed. This means that when children act out in a disturbing manner, they are not only confused and overwhelmed, but they cannot even remember what is safe and what is not safe.

Traditionally, we have seen children as being willfully disobedient and manipulative. This stems from a belief that in the moments of being disobedient and manipulative, they also have full cognitive and conscious awareness of their actions. Unfortunately for both parents and children, this could not be further from the truth. Stress constricts their thinking, distorts their perspective, and short-circuits their short-term memory.

Children diagnosed with reactive attachment disorder, oppositional- defiant disorder, bipolar, and other such psychiatric diagnoses, have almost all experienced some degree of trauma in their lifetimes. The trauma can be anywhere on the continuum – from mild, to moderate, to severe. Generally the children we will be referring to in the following pages have experienced specific traumas along the moderate to severe range. And what is significant is that for most of these children, the earliest traumas experienced have since been compounded and overlaid with more childhood trauma. Examples of such trauma can be seen in the following chart.

Childhood traumas are not limited to those on this list.

When a child experiences trauma, the child’s ability to develop a sufficient regulatory system is severely compromised. In cases of severe trauma, the child’s life is literally at risk. For these children, their internal survival mechanisms then become activated, dedicating all the body’s resources to remain alert in “survival mode.” These children perceive the world as threatening from a neurological, physical, emotional, cognitive, and social perspective. They operate from a paradigm of fear to ensure their safety and security. Hence, what is seen is an overly stressed-out child who has difficulty interacting in relationships, who struggles to behave in a loving way, who quite often cannot think clearly, and who swings back and forth in his emotional states due to an underdeveloped regulatory system. While perceived by most professionals as dangerous, a child of trauma is essentially a scared child – a stressed child living out of a primal, survival mode in order to maintain his existence.

These traumatic experiences are stored, and for most children are buried, as unprocessed and unexpressed memories within the body/mind system. According to neuroscientist Bruce D. Perry, M.D., we have four levels of memory: cognitive, emotional, motor, and state.2 It is in the deepest level of memory, the state memory, that these experiences are stored. The significance of this is that when our state memory is activated, it directs all of our responses. It has the ability to dominate over the other three memory states. To understand this further, let us take a look at all four of our memory states: cognitive, emotional, motor, and state.

Cognitive. Our cognitive memory allows us to have immediate recall. It is the level of memory where we store facts, data, dates, research, names, numbers, etc. We generally have immediate access to this level of memory.

Emotional. For every cognitive memory, there is a corresponding emotional memory attached to it. However, at the emotional level, the cognitive and emotional memories may not always be easily connected. You may not always have access to the cognitive memory, even though you may have access to the emotional memory. For example, say you have a friend from high school or college that you have not seen for some years. While you can remember the face, you are unable to remember the name. Yet, attached to the memory of the face of this person is a very pleasant and warm feeling – the emotional memory. Additionally, events happening in our lives which are emotionally impacting become easily accessible at the emotional level of memory. If you were asked where you were on 9/11, you would probably remember the exact time of day and your location when you received the news of the terrorist attacks. However, if I asked you where you were last Friday, your memory of this day would more than likely be clouded, at best. This memory is not easily accessible because the events that happened on that day were probably not emotionally significant.

Motor. The motor memory is our body level of memory. For the most part, we seldom think about this level of memory and operate on automatic pilot. When you get into your car and begin driving, you seldom think about pulling open the door handle, putting the key into the ignition, or putting your arm over the passenger seat as you begin to back up. As you continue in the automatic mode, you have suddenly arrived at work and think, “How did I get here?” This level of memory is very unconscious.

State. The state level of memory is the level of memory most associated with your personality traits. It lies in direct reference point to your brainstem. In other words, it is located in your lower limbic system or your reptilian brain. This area of your brain is not part of your rational brain but rather a part of your emotional brain. It is responsible for processing raw data from the environment and sending immediate signals of fight, flee, or freeze. This holds great significance for traumatized children due to the fact that traumatic memories get stored at the state level. When a per son reaches a heightened state of stress, this state memory gets triggered, thereby releasing all previous relevant memories into the upper memory banks. In this manner, when a child with a traumatic history is confronted with a situation which heightens his level of stress, the child’s state memory becomes activated. Rapid-fire communications to the other areas of the memory system are initiated, informing the child that the current situation is threatening. Additionally, this rapid-fire communication is also telling the child that this situation is almost guaranteed to workout like a previously stored experience. In other words, in the midst of a stressful or perceived threatening event, this child, due to his cognitively distorted state of mind, is likely to believe deep within the very cells of his body that if he doesn’t convince this person right now that he is telling the truth, then in all likelihood he might be abused, abandoned, neglected, or worse – he might die! Faced with this looming threat, this child is most likely going to tell a lie, despite his understanding at the cognitive level that lies are morally and ethically wrong. In the midst of stress and threat, the state memory can completely override all other memory states.

Now it may seem like a far stretch to consider such possibilities for this child, especially over something as simple as stealing a cookie. You’re asking, “How can stealing a cookie be linked to the threat of death?” Yet, nothing could come closer to truly understanding this child’s experience when confronted with the theft of a cookie. His state level of memory is activated, linking past traumatic experiences to the present situation. Thus, it is no longer just about the cookie. For the child, it is about survival – life or death. Through the comprehension of this fear dynamic, we can begin to understand why such children are prone to repetitive, negative behaviors, such as lying. If you had the belief at the cellular level that lying would ensure your survival and safety, wouldn’t you continue this behavior?

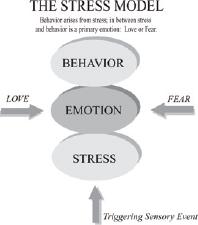

All the behaviors discussed in this book are based on one simple model: The Stress Model. The Stress Model was developed by this author, Bryan Post, LCSW, as a model to explain human behavior. The Stress Model is a regulatory theory of human behavior based on findings from the field of neurophysiology and studies regarding affect regulation. It really is simple, so read on....

According to the Stress Model, all behavior arises from a state of stress; and between the behavior and the stress is the presence of a primary emotion. There are only two primary emotions: Love and Fear. It is through the expression, processing, and understanding of the primary emotion that you can calm the stress and diminish the behavior.

When the stress model is understood, it can be applied to any complex family situation in order to find a simple, loving approach to help all family members. We must first see that there are only two emotions: love and fear. From love, only loving feelings – such as joy and happiness – can be present. From love, only loving behaviors – such as reciprocity, empathy, conscience, and the ability to understand deeply the experience of others – can be exhibited. Likewise, from fear, only fear-based feelings – such as anger, frustration, shame, blame, and envy – can be present. From fear, only fear-based behaviors – such as hitting, fighting, arguing, lying, stealing, defiance and hostility – can be exhibited (see chart below).

When seeking to understand children of trauma, we must fully comprehend that at their deepest core is an emotional state of fear. What we see on the outside is anger, defiance, stealing, killing animals, setting fires, etc. These fear-based behaviors rapidly create fear within us. Thus, we become constricted and angered by the behaviors that can literally scare us to death.

Remember, however, that these are merely behaviors – manifestations of the fear that is underneath it all. In order to change these scary behaviors, we must first address the fear. When we are able to help our child calm his fear, the fear-based behaviors will dissipate. As you read through the following chapters, examples will be given to show how simple parenting responses can accomplish this. The hardest part of implementing this model will be in dealing with your own fear that arises from the behaviors of your child. This is a critical part of your parenting because in order to help your child move out of his fear, you must have first addressed your own fear. Impossible? No. Difficult? Yes.

What makes this difficult is that neither children nor adults are fully conscious of their initial states of stress that occur at the body level. Before we ever become aware of it consciously or cognitively, we will have already had a stress reaction. For simplicity’s sake, but not to downplay the profound impact of this dynamic, let us take the example of hearing a door slam. Immediately upon hearing the slam, you have a startle reaction; your body becomes suddenly alert. Before you will have had any conscious or cognitive awareness of exactly what made you startle, your body will have already reacted. This is considered to be an unconscious reaction. Candace Pert, the author of the ground-breaking book, Molecules of Emotion, tells us that any visual cue – or anything that we see with our eyes – must pass through seven different synapses in our brain before it ever becomes an actual conscious thought.3

The implications for this, as it applies to children who are overly sensitive due to traumatic experience (you do not have a child diagnosed Reactive Attachment Disorder or Oppositional Defiant Disorder without some degree of trauma in his history) are profound. The majority of early development and interaction for a child is emotionally driven; hence, the majority of childhood engagement is unconscious. Considering this, we must understand that when a child feels stressed or threatened to any degree, his behavior will arise from an unconscious place. There is no such thing as willful disobedience or manipulation without first the seeds of fear and stress.

Remember that the negative behaviors we will be discussing have arisen first from an unconscious, fear-based place of stress, as opposed to any clear cognitive or conscious place. Stress causes confused and distorted thinking: therefore, if a child has done or is doing something that you know is not in line with a loving relationship, the child must obviously be coming from a place of stress and fear. And certainly if the child had the conscious ability to recognize such a state, he would begin making attempts to do so; however, with such behavior being unconscious, in that moment the child is doing the best that he can to survive.