Two military disasters defined the trajectory of the Habsburg Empire in the last half-century of its existence. At Solferino in 1859, French and Piedmontese forces prevailed over an army of 100,000 Austrian troops, opening the way to the creation of a new Italian nation-state. At Königgrätz in 1866, the Prussians destroyed an Austrian army of 240,000, ejecting the empire from the emergent German nation-state. The cumulative impact of these shocks transformed the inner life of the Austrian lands.

Shaken by military defeat, the neo-absolutist Austrian Empire metamorphosed into the Austro-Hungarian Empire. Under the Compromise hammered out in 1867, power was shared out between the two dominant nationalities, the Germans in the west and the Hungarians in the east. What emerged was a unique polity, like an egg with two yolks, in which the Kingdom of Hungary and a territory centred on the Austrian lands and often called Cisleithania (meaning ‘the lands on this side of the River Leithe’) lived side by side within the translucent envelope of a Habsburg dual monarchy. Each of the two entities had its own parliament, but there was no common prime minister and no common cabinet. Only foreign affairs, defence and defence-related aspects of finance were handled by ‘joint ministers’ who were answerable directly to the Emperor. Matters of interest to the empire as a whole could not be discussed in common parliamentary session, because to do so would have implied that the Kingdom of Hungary was merely the subordinate part of some larger imperial entity. Instead, an exchange of views had to take place between the ‘delegations’, groups of thirty deputies from each parliament, who met alternately in Vienna and Budapest.

The dualist compromise had many enemies at the time and has had many critics since. In the eyes of hardline Magyar nationalists, it was a sell-out that denied the Hungarians the full national independence that was their due. Some claimed that Austria was still exploiting the Kingdom of Hungary as an agrarian colony. Vienna’s refusal to relinquish control over the armed forces and create a separate and equal Hungarian army was especially contentious – a constitutional crisis over this question paralysed the empire’s political life in 1905.1 On the other hand, Austrian Germans argued that the Hungarians were freeloading on the more advanced economy of the Austrian lands, and ought to pay a higher share of the empire’s running costs. Conflict was programmed into the system, because the Compromise required that the two imperial ‘halves’ renegotiate every ten years the customs union by which revenues and taxation were shared out between them. The demands of the Hungarians became bolder with every review of the union.2 And there was little in the Compromise to recommend it to the political elites of the other national minorities, who had in effect been placed under the tutelage of the two ‘master races’. The first post-Compromise Hungarian prime minister, Gyula Andrássy, captured this aspect of the settlement when he commented to his Austrian counterpart: ‘You look after your Slavs and we’ll look after ours.’3 The last decades before the outbreak of war were increasingly dominated by the struggle for national rights among the empire’s eleven official nationalities – Germans, Hungarians, Czechs, Slovaks, Slovenes, Croats, Serbs, Romanians, Ruthenians, Poles and Italians.

How these challenges were met varied between the two imperial halves. The Hungarians dealt with the nationalities problem mainly by behaving as if it didn’t exist. The kingdom’s electoral franchise extended to only 6 per cent of the population because it was pegged to a property qualification that favoured the Magyars, who made up the bulk of the wealthier strata of the population. The result was that Magyar deputies, though they represented only 48.1 per cent of the population, controlled over 90 per cent of the parliamentary seats. The 3 million Romanians of Transylvania, the largest of the kingdom’s national minorities, comprised 15.4 per cent of the population, but held only five of the Hungarian parliament’s 400-odd seats.4 From the late 1870s, moreover, the Hungarian government pursued a campaign of aggressive ‘Magyarization’. Education laws imposed the use of the Magyar language on all state and faith schools, even those catering to children of kindergarten age. Teachers were required to be fluent in Magyar and could be dismissed if they were found to be ‘hostile to the [Hungarian] state’. This degradation of language rights was underwritten by harsh measures against ethnic minority activists.5 Serbs from the Vojvodina in the south of the kingdom, Slovaks from the northern counties and Romanians from the Grand Duchy of Transylvania did occasionally collaborate in pursuit of minority objectives, but with little effect, since they could muster only a small number of mandates.

In Cisleithania, by contrast, successive administrations tampered endlessly with the system in order to accommodate minority demands. Franchise reforms in 1882 and 1907 (when virtually universal male suffrage was introduced) went some way towards levelling the political playing field. But these democratizing measures merely heightened the potential for national conflict, especially over the sensitive question of language use in public institutions such as schools, courts and administrative bodies.

Nowhere were the frictions generated by nationalist politics more in evidence than in the Cisleithanian parliament, which met from 1883 in a handsome neo-classical building on Vienna’s Ringstrasse. In this 516-seat legislature, the largest in Europe, the familiar spectrum of party-political ideological diversity was cross-cut by national affiliations producing a panoply of splinter groups and grouplets. Among the thirty-odd parties that held mandates after the 1907 elections, for example, were twenty-eight Czech Agrarians, eighteen Young Czechs (Radical nationalists), seventeen Czech Conservatives, seven Old Czechs (moderate nationalists), two Czech-Progressives (Realist tendency), one ‘wild’ (independent) Czech and nine Czech National Socialists. The Poles, the Germans, the Italians and even the Slovenes and the Ruthenes were similarly divided along ideological lines.

Since there was no official language in Cisleithania (by contrast with the Kingdom of Hungary), there was no single official language of parliamentary procedure. German, Czech, Polish, Ruthenian, Croat, Serbian, Slovenian, Italian, Romanian and Russian were all permitted. But no interpreters were provided, and there was no facility for recording or monitoring the content of speeches that were not in German, unless the deputy in question himself chose to supply the house with a translated text of his speech. Deputies from even the most insignificant factions could thus block unwelcome initiatives by delivering long speeches in a language that only a handful of their colleagues understood. Whether they were actually addressing the issues raised by the current motion, or simply reciting long poems in their own national idiom, was difficult to ascertain. The Czechs in particular were renowned for the baroque extravagance of their filibustering.6 The Cisleithanian parliament became a celebrated tourist attraction, especially in winter, when Viennese pleasure-seekers crowded into the heated visitors’ galleries. By contrast with the city’s theatres and opera houses, a Berlin journalist wrily observed, entry to parliamentary sessions was free.*

So intense did the national conflict become that in 1912–14 multiple parliamentary crises crippled the legislative life of the monarchy: the Bohemian Diet had become so obstreperous by 1913 that the Austrian prime minister, Count Karl Stürgkh, dissolved it, installing in its place an imperial commission tasked to govern the province. Czech protests against this measure brought the Cisleithanian parliament to its knees in March 1914. On 16 March, Stürgkh dismissed this assembly too – it was still in suspension when Austria-Hungary declared war on Serbia in July, so that Cisleithania was in effect being run under a kind of administrative absolutism when the war broke out. Things were not much better in Hungary: in 1912, following protests in Zagreb and other South Slav cities against an unpopular governor, the Croatian Diet and constitution were suspended; in Budapest itself, the last pre-war years witnessed the advent of a parliamentary absolutism focused on protecting Magyar hegemony against the challenge posed by minority national opposition and the demand for franchise reform.7

These spectacular symptoms of dysfunctionality might appear to support the view that the Austro-Hungarian Empire was a moribund polity, whose disappearance from the political map was merely a matter of time: an argument deployed by hostile contemporaries to suggest that the empire’s efforts to defend its integrity during the last years before the outbreak of war were in some sense illegitimate.8 In reality, the roots of Austria-Hungary’s political turbulence went less deep than appearances suggested. There was, to be sure, intermittent ethnic conflict – riots in Ljubljana in 1908 for example, or periodic Czech–German brawls in Prague – but it never came close to the levels of violence experienced in the contemporary Russian Empire, or in twentieth-century Belfast. As for the turbulence of the Cisleithanian parliament, it was a chronic ailment, rather than a terminal disease. The business of government could always be carried on temporarily under the emergency powers provided under Clause 14 of the 1867 Constitution. To a certain extent, moreover, different kinds of political conflict cancelled each other out. The conflict between socialists, liberals, clerical conservatives and other political groupings after 1907 was a boon to the Austrian part of the monarchy, because it cut across the national camps and thereby undermined the virulence of nationalism as a political principle. Balancing the complex array of forces that resulted to sustain a working majority was a complex task requiring tact, flexibility and strategic imagination, but the careers of the last three Austrian prime ministers before 1914, Beck, Bienerth and Stürgkh, showed – despite intermittent breakdowns in the system – that it could be done.9

The Habsburg lands passed during the last pre-war decade through a phase of strong economic growth with a corresponding rise in general prosperity – an important point of contrast with the contemporary Ottoman Empire, but also with another classic collapsing polity, the Soviet Union of the 1980s. Free markets and competition across the empire’s vast customs union stimulated technical progress and the introduction of new products. The sheer size and diversity of the double monarchy meant that new industrial plants benefited from sophisticated networks of cooperating industries underpinned by an effective transport infrastructure and a high-quality service and support sector. The salutary economic effects were particularly evident in the Kingdom of Hungary. In the 1840s, Hungary really had been the larder of the Austrian Empire – 90 per cent of its exports to Austria consisted of agricultural products. But by the years 1909–13, Hungarian industrial exports had risen to 44 per cent, while the constantly growing demand for cheap foodstuffs of the Austro-Bohemian industrial region ensured that the Hungarian agricultural sector survived in the best of health, protected by the Habsburg common market from Romanian, Russian and American competition.10 For the monarchy as a whole, most economic historians agree that the period 1887–1913 saw an ‘industrial revolution’, or a take-off into self-sustaining growth, with the usual indices of expansion: pig-iron consumption increased fourfold between 1881 and 1911, railroad coverage did the same between 1870 and 1900, and infant mortality decreased, while elementary schooling figures surpassed those in Germany, France, Italy and Russia.11 In the last years before the war, Austria-Hungary, and Hungary in particular (with an average annual growth of 4.8 per cent), was one of the fastest-growing economies in Europe.12

Even a critical observer like the Times correspondent Henry Wickham Steed, a long-time resident of Vienna, recognized in 1913 that ‘the “race struggle” in Austria’ was in essence a conflict for shares of patronage within the existing system:

The essence of the language struggle is that it is a struggle for bureaucratic influence. Similarly, the demands for new Universities or High Schools put forward by Czechs, Ruthenes, Slovenes, and Italians but resisted by the Germans, Poles, or other races, as the case may be, are demands for the creation of new machines to turn out potential officials whom the political influence of Parliamentary parties may then be trusted to hoist into bureaucratic appointments.13

There was, moreover, slow but unmistakable progress towards a more accommodating policy on national rights (at least in Cisleithania). The equality of all the subject nationalities and languages in Cisleithania was formally recognized in the Basic Law of 1867, and a body of case law accumulated to provide solutions for problems the drafters of the Compromise had not foreseen, such as language provisions for Czech minorities in German areas of Bohemia. Throughout the last peacetime years of the empire’s existence, the Cisleithanian authorities continued to adjust the system in response to national minority demands. The Galician Compromise agreed in the Galician Diet in Lemberg (today Lviv) on 28 January 1914, for example, assured a fixed proportion of the mandates in an enlarged regional legislature to the under-represented Ruthenes (Ukrainians) and promised the imminent establishment of a Ukrainian university.14 Even the Hungarian administration was showing signs of a change of heart by the beginning of 1914, as the international climate worsened. The South Slavs of Croatia-Slavonia were promised the abolition of extraordinary powers and a guarantee of freedom of the press, while a message went out to Transylvania that the Budapest government intended to meet many of the demands of the Romanian majority in that region. The Russian foreign minister, Sergei Sazonov, was so impressed by the thought that these measures might stabilize Habsburg rule in the Romanian areas that he proposed to Tsar Nicholas II in January 1914 granting similar concessions to the millions of Poles in western Russia.15

These case-by-case adjustments to specific demands suggested that the system might eventually produce a comprehensive mesh of guarantees for nationality rights within an agreed framework.16 And there were signs that the administration was getting better at responding to the material demands of the regions.17 It was the state, of course, that performed this role, not the beleaguered parliaments of the Habsburg lands. The proliferation of school boards, town councils, county commissions, mayoral elections and the like ensured that the state intersected with the life of the citizenry in a more intimate and consistent way than the political parties or the legislative assemblies.18 It was not (or not primarily) an apparatus of repression, but a vibrant entity commanding strong attachments, a broker among manifold social, economic and cultural interests.19 The Habsburg bureaucracy was costly to maintain – expenditure for the domestic administration rose by 366 per cent during the years 1890–1911.20 But most inhabitants of the empire associated the Habsburg state with the benefits of orderly government: public education, welfare, sanitation, the rule of law and the maintenance of a sophisticated infrastructure.21 These features of the Habsburg polity loomed large in memory after the monarchy’s extinction. In the late 1920s, when the writer (and engineering graduate) Robert Musil looked back on the Austro-Hungarian Empire in the last peaceful year of its existence, the picture that formed before his mind’s eye was one of ‘white, broad, prosperous streets [. . .] that stretched like rivers of order, like ribbons of bright military serge, embracing the lands with the paper-white arm of administration’.22

Finally, most minority activists acknowledged the value of the Habsburg commonwealth as a system of collective security. The bitterness of conflicts between minority nationalities – Croats and Serbs in Croatia-Slavonia, for example, or Poles and Ruthenians in Galicia – and the many areas of ethnically mixed settlement suggested that the creation of new and separate national entities might cause more problems than it resolved.23 And how, in any case, would such fledgeling nation-states fare without the protective carapace of the empire? In 1848, the Czech nationalist historian František Palacky had warned that disbanding the Habsburg Empire, far from liberating the Czechs, would merely provide the basis for ‘Russian universal monarchy’. ‘I am impelled by natural as well as historical causes to seek [in Vienna] the centre called to secure and to protect for my people peace, freedom and justice.’24 In 1891, Prince Charles Schwarzenberg advanced the same argument when he asked the Young Czech nationalist Edward Grégr: ‘If you and yours hate this state, . . . what will you do with your country, which is too small to stand alone? Will you give it to Germany, or to Russia, for you have no other choice if you abandon the Austrian union.’25 Before 1914, radical nationalists seeking full separation from the empire were still a small minority. In many areas, nationalist political groups were counterbalanced by networks of associations – veterans’ clubs, religious and charitable groups, associations of bersaglieri (sharpshooters) – nurturing various forms of Habsburg patriotism.26

The venerability and permanence of the monarchy were personified in the imperturbable, bewhiskered figure of Emperor Franz Joseph. His had been a life abnormally rich in private tragedy. The Emperor’s son Rudolf had killed himself in a double suicide with his mistress at the family hunting lodge, his wife Elisabeth (‘Sissi’) had been stabbed to death by an Italian anarchist on the banks of Lake Geneva, his brother Maximilian had been executed by Mexican insurgents at Queretaro and his favourite niece had burned to death when a cigarette set fire to her dress. The Emperor had borne these blows with a glacial stoicism. In public life, he projected a persona ‘demonic’, as the satirist Karl Kraus put it, in its ‘unpersonality’. His stylized commentary on virtually every official ceremony – ‘It was nice, we were quite pleased’ – was a household phrase across the lands of the monarchy.27 The Emperor demonstrated considerable skill in managing the complex machinery of his state, balancing opposed forces in order to maintain all within an equilibrium of well-tempered dissatisfaction and involving himself closely in all phases of constitutional reform.28 Yet by 1914 he had become a force for inertia. In the last two years before the war, he backed the autocratic Magyar premier István Tisza against minority demands for Hungarian franchise reform. As long as the Kingdom of Hungary continued to deliver the funds and votes Vienna needed, Franz Joseph was prepared to accept the hegemony of the Magyar elite, notwithstanding its disregard for the interests of the national minorities in the lands of the kingdom.29 There were signs that he was drifting out of touch with contemporary life: ‘The powerfully surging life of our times,’ wrote the Austrian German politician Joseph Maria Baernreither in 1913, when Franz Joseph was eighty-three, ‘scarcely reaches the ear of our emperor as distant rustling. He is denied any real participation in this life. He no longer understands the times, and the times pass on regardless.’30

Nevertheless: the Emperor remained the focus of powerful political and emotional attachments. It was widely recognized that his popularity was anchored outside of his constitutional role, in broadly shared popular emotions.31 By 1914, he had been on the throne for longer than most of his subjects had been alive. He seemed, in the words of Joseph Roth’s masterpiece The Radetzky March, ‘coffered up in an icy and everlasting old age, like armour of an awe-inspiring crystal’.32 He made regular appearances in the dreams of his subjects. His sky-blue eyes continued to gaze out from portraits across tens of thousands of taverns, schoolrooms, offices and railway waiting rooms, while the daily newspapers marvelled at the supple and elastic stride with which the old man leapt from his carriage on state occasions. Prosperous and relatively well administered, the empire, like its elderly sovereign, exhibited a curious stability amid turmoil. Crises came and went without appearing to threaten the existence of the system as such. The situation was always, as the Viennese journalist Karl Kraus quipped, ‘desperate, but not serious’.

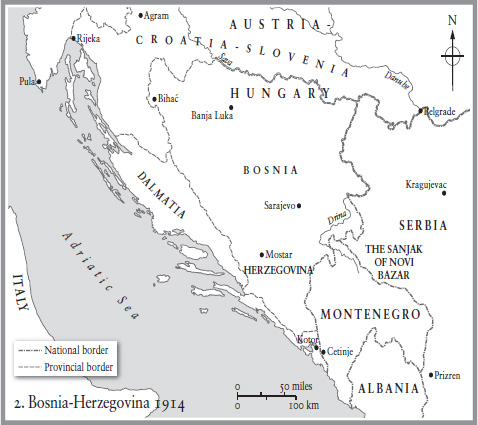

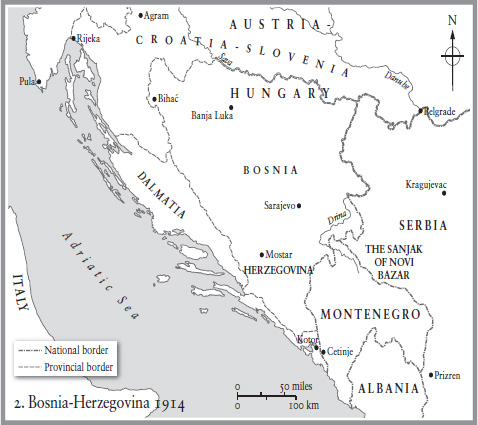

A special and anomalous case was Bosnia-Herzegovina, which the Austrians ‘occupied’ under Ottoman suzerainty in 1878 on the authorization of the Treaty of Berlin and formally annexed thirty years later. Late nineteenth-century Bosnia was a heavily forested, mountainous land bounded by peaks of over 2,000 metres in the south and by valley of the river Save in the north. Herzegovina consisted mainly of a wild, high karst plateau crossed by swift watercourses and closed in by mountain chains – a land of harsh terrain and virtually non-existent infrastructure. The condition of these two Balkan provinces under Habsburg rule has long been the subject of controversy. The young Bosnian Serb terrorists who travelled to Sarajevo in the summer of 1914 to kill the heir to the Austrian throne defended their actions by reference to the oppression of their brothers in Bosnia and Herzegovina, and historians have sometimes suggested that the Austrians themselves were to blame for driving the Bosnian Serbs into the arms of Belgrade by a combination of oppression and misgovernment.

Is this right? There were widespread protests during the early years of the occupation, especially against conscription. But this was nothing new – the provinces had experienced chronic turbulence under Ottoman rule; what was exceptional was the relative serenity of the period from the mid-1880s down to 1914.33 The condition of the peasantry after 1878 was a sore point. The Austrians chose not to abolish the Ottoman agaluk estate system, on which about 90,000 Bosnian serfs or kmets were still working in 1914, and some historians have seen this as evidence of a ‘divide and rule’ policy designed to press down the mainly Serb peasantry while currying favour with the Croats and Muslims in the towns. But this is a retrospective projection. Cultural and institutional conservatism, not a philosophy of colonial domination, underpinned Austrian governance in the new provinces. ‘Gradualism and continuity’ characterized Austrian rule in all areas of Bosnia-Herzegovina where they encountered traditional institutions.34 Where possible, the laws and institutions inherited from the Ottoman era were harmonized and clarified, rather than discarded out of hand. But the Habsburg administration did facilitate the emancipation of subject peasants by means of a one-off payment; over 40,000 Bosnian kmets purchased their autonomy in this way between the occupation and the outbreak of war in 1914. In any case, the Serbian kmets who remained within the old estate system on the eve of the First World War were not especially badly off by the standards of early twentieth-century peasant Europe; they were probably more prosperous than their counterparts in Dalmatia or southern Italy.

The Austrian administration also did much to increase the productivity of agriculture and industry in Bosnia-Herzegovina. They set up model farms, including a vineyard and a fish-farm, introduced rudimentary agronomic training for country schoolteachers and even established an agricultural college in Ilidze, at a time when no such institution existed in neighbouring Serbia. If the uptake of new methods was still relatively slow, this had more to do with the resistance of the peasantry to innovation than with Austrian negligence. There was also a massive influx of investment capital. A road and railway network appeared, including some of the best mountain roads in Europe. These infrastructural projects served a partly military purpose, to be sure, but there was also massive investment across a range of sectors, including mining, metallurgy, forestry and chemicals production. The pace of industrialization peaked during the administration of Count Benjamin Kállay (1882–1903) and the consequence was a surge in industrial output (12.4 per cent per annum on average over the period 1881–1913) without precedent elsewhere in the Balkan lands.35 In short, the Habsburg administration treated the new provinces as a showcase whose purpose was to ‘demonstrate the humanity and efficiency of Habsburg rule’; by 1914, Bosnia-Herzegovina had been developed to a level comparable with the rest of the double monarchy.36

The worst blemish on the record of the Austrian administration in Bosnia-Herzegovina was the appallingly low rate of literacy and school attendance, which was worse even than Serbia’s.37 But this was not the consequence of an Austrian policy of mass stultification. The Austrians built primary schools – nearly 200 of them – not to mention three high schools, a teacher training college and a technical institute. It was not a stellar effort, but it was not outright neglect either. The problem lay partly in getting peasants to send their children to school.38 Only in 1909, after the formal annexation of the provinces, was compulsory primary education introduced.

All was not sweetness and light in Bosnia-Herzegovina, to be sure. The Habsburg administration bore down hard on anything that smelled like nationalist mobilization against the empire, sometimes with a heavy and undiscriminating hand. In 1913, Oskar Potiorek, military governor of Bosnia-Herzegovina, suspended most of the Bosnian constitution of 1910, tightened government controls of the school system, banned the circulation of newspapers from Serbia and closed down many Bosnian Serb cultural organizations, though this was, it should be pointed out, in response to an escalation in Serbian ultra-nationalist militancy.39 Another vexing factor was the political frustration of Serbs and Croats just across the border to the west and north in Croatia-Slavonia, and to the east in the Vojvodina, both ruled from Budapest under the restrictive Hungarian franchise. But all in all, this was a relatively fair and efficient administration informed by a pragmatic respect for the diverse traditions of the national groups in the provinces. Theodore Roosevelt was not too far off the mark when he observed, during a visit to the White House by two senior Austrian politicians in June 1904, that the Habsburg monarchy had ‘understood how to treat the different nations and religions in this country on an equal footing and how thereby to achieve such great successes’; he added, perhaps unhappily, that he believed the US administration in the Philippines could learn a lot from the Austrian example.40 Visitors, too, were struck by the even-handedness of the Habsburg regime: there was a tone of ‘mutual respect and mutual toleration’ among the ethno-religious groups, one American journalist observed in 1902; the courts were ‘wisely and honestly administered’ and ‘justice [was] awarded to every citizen, regardless of his religion or social position’.41

Evaluating the condition and prospects of the Austro-Hungarian Empire on the eve of the First World War confronts us in an acute way with the problem of temporal perspective. The collapse of the empire amid war and defeat in 1918 impressed itself upon the retrospective view of the Habsburg lands, overshadowing the scene with auguries of imminent and ineluctable decline. The Czech national activist Edvard Beneš was a case in point. During the First World War, Beneš became the organizer of a secret Czech pro-independence movement; in 1918, he was one of the founding fathers of the new Czechoslovak nation-state. But in a study of the ‘Austrian Problem and the Czech Question’ published in 1908, he had expressed confidence in the future of the Habsburg commonwealth. ‘People have spoken of the dissolution of Austria. I do not believe in it at all. The historic and economic ties which bind the Austrian nations to one another are too strong to let such a thing happen.’42 A particularly striking example is the sometime Times correspondent (later editor) Henry Wickham Steed. In 1954, Steed declared in a letter to the Times Literary Supplement that when he had left the Austro-Hungarian Empire in 1913, ‘it was with the feeling that I was escaping from a doomed edifice’. His words confirmed what was then the widely held view. Back in 1913, however, he had seen things differently. Though he was an outspoken critic of many features of Habsburg governance, he wrote in that year that he had been unable during ten years of ‘constant observation and experience’ to perceive ‘any sufficient reason’ why the Habsburg monarchy ‘should not retain its rightful place in the European Community’. ‘Its internal crises,’ he concluded, ‘are often crises of growth rather than crises of decay.’43 It was only during the First World War that Steed became a propagandist for the dismemberment of the Austro-Hungarian state and an ardent defender of the post-war settlement in Central Europe. For the 1927 English translation of Tomáš Masaryk’s Czech nationalist memoir The Making of a State, Steed supplied a foreword in which he declared that the name ‘Austria’ was synonymous with ‘every device that could kill the soul of a people, corrupt it with a modicum of material well-being, deprive it of freedom of conscience and of thought, undermine its sturdiness, sap its steadfastness and turn it from the pursuit of its ideal’.44

Such reversals of polarity could occur in the other direction too. The Hungarian scholar Oszkár Jászi – one of the most profound experts on the Habsburg Empire – was sharply critical of the dualist system. In 1929, he concluded an ambitious study of the monarchy’s dissolution with the observation that ‘the World War was not the cause, but only the final liquidation of the deep hatred and distrust of the various nations’.45 And yet in 1949, after a further world war and a calamitous period of dictatorship and genocide in his home country, Jászi, who had lived in American exile since 1919, struck a different note. In the old Habsburg monarchy, he wrote, ‘the rule of law was tolerably secure; individual liberties were more and more recognised; political rights continuously extended; the principle of national autonomy growingly respected. The free flow of persons and goods extended its benefits to the remotest parts of the monarchy’.46 While the euphoria of national independence disposed some who had once been loyal Habsburg citizens to impugn the old dual monarchy, others who were vigorous dissenters before 1914 later fell prey to nostalgia. In 1939, reflecting on the collapse of the monarchy, the Hungarian writer Mihály Babits wrote: ‘we now regret the loss and weep for the return of what we once hated. We are independent, but instead of feeling joy we can only tremble.’47

After the ejection of the Austrians from Italy in 1859 and Germany in 1866, the Balkan region became by default the pre-eminent focus of Austro-Hungarian foreign policy. Unfortunately, this narrowing of geopolitical range happened to coincide with an era of growing volatility across the Balkan peninsula. The underlying problem was the waning of Ottoman authority in south-eastern Europe, which created a zone of tension between the two great powers with a strategic interest in the region.48 Both Russia and Austria-Hungary felt historically entitled to exercise hegemony in those areas from which the Ottomans withdrew. The House of Habsburg had traditionally been the guardian of Europe’s eastern gate against the Turks. In Russia, the ideology of pan-Slavism asserted a natural commonality of interest between the emergent Slavic (especially Orthodox) nations of the Balkan peninsula and the patron power in St Petersburg. Ottoman retreat also raised questions about future control of the Turkish Straits, an issue of acute strategic importance to Russian policy-makers. At the same time, ambitious new Balkan states emerged with conflicting interests and objectives of their own. Across this turbulent terrain, Austria and Russia manoeuvred like chess players hoping with each move to cancel out or diminish the opponent’s advantage.

Until 1908, cooperation, self-restraint and the demarcation of informal spheres of influence ensured that the dangers implicit in this state of affairs were contained.49 In the revised Three Emperors’ League treaty of 1881 between Russia, Austria-Hungary and Germany, Russia undertook to ‘respect’ the Austro-Hungarian occupation of Bosnia-Herzegovina authorized in 1878 at the Treaty of Berlin and the three signatories agreed to ‘take account’ of each other’s ‘interests in the Balkan Peninsula’.50 Further Austro-Russian understandings in 1897 and 1903 reaffirmed the joint commitment to the Balkan status quo.

The complexity of Balkan politics was such, however, that maintaining good relations with the rival great power was not enough to ensure tranquillity. The lesser beasts of the peninsula also had to be placated and tamed. And the most important of these, from Vienna’s standpoint, was the Kingdom of Serbia. During the long reign of the Austrophile Milan Obrenović, Serbia remained a docile partner in Vienna’s designs, acquiescing in the empire’s claim to regional hegemony. Vienna, in return, supported Belgrade’s bid for elevation to the status of kingdom in 1882 and promised diplomatic support in the event that Serbia should seek to expand southwards into Ottoman Macedonia. As the Austro-Hungarian foreign minister, Gustav Count Kálnoky von Köröspatak, informed his Russian counterpart in the summer of 1883, good relations with Serbia were the keystone of the empire’s Balkan policy.51

Though friendly, King Milan of Serbia could be an exasperating partner. In 1885 the king created a commotion in Vienna by proposing to abdicate, send his son to school in Austria and allow the empire to annex his kingdom. The Austrians were having none of this nonsense. At a meeting in Vienna the dejected monarch was reminded of his kingly duties and sent back to Belgrade. ‘A flourishing and independent Serbia,’ Kálnoky explained to the Austrian prime minister, ‘suits our intentions [. . .] better than the possession of an unruly province.’52 On 14 November, however, only four months after appearing to lose his will to rule, Milan suddenly and unexpectedly invaded neighbouring Bulgaria, Russia’s client state. The resulting conflict was shortlived, because the Serbian army was easily beaten back by the Bulgarians, but assiduous great power diplomacy was required to prevent this unexpected démarche from ruffling the feathers of the Austro-Russian détente.

The son proved even more erratic than the father: Alexandar boasted intemperately of Austro-Hungarian support for his kingdom and declared publicly in 1899 that ‘the enemies of Serbia are the enemies of Austria-Hungary’ – a faux pas that raised eyebrows in St Petersburg and caused considerable embarrassment in Vienna. But he was also tempted by the advantages of a Russophile policy; by 1902, after the death of King Father Milan, King Alexandar was energetically suing for Russian support; he even declared to a journalist in St Petersburg that the Habsburg monarchy was ‘the arch enemy of Serbia’.53 There was thus little regret in Vienna at the news of Alexandar’s premature death, although the politicians there were as shocked as everyone else by the brutality with which he and his line were exterminated.

Only gradually did it become clear to the Austrians that the regicide of June 1903 marked a real break. The foreign ministry in Vienna hastened to establish good relations with the usurper Petar Karadjordjević, whom they optimistically viewed as Austrophile in temperament. Austria-Hungary became the first foreign state to recognize formally the new Serbian regime. But it soon became clear that the foundations no longer existed for a harmonious relationship between the two neighbours. The management of political affairs passed into the hands of men openly hostile to the dual monarchy and the policy-makers in Vienna studied with growing concern the nationalist expectorations of the Belgrade press, now freed from governmental restraints. In September 1903, Konstantin Dumba the Austrian minister in Belgrade reported that relations between the two countries were ‘as bad as possible’. Vienna rediscovered its moral outrage at the regicide and joined the British in imposing sanctions on the Karadjordjević court. Hoping to profit from this loosening of the Austro-Serbian bond, the Russians moved in, assuring the Belgrade government that Serbia’s future lay in the west, on the Adriatic coastline, and urging them not to renew their long-standing commercial treaty with Vienna.54

At the end of 1905, these tensions broke out into open conflict with the discovery in Vienna that Serbia and Bulgaria had signed a ‘secret’ customs union. Vienna’s demand early in 1906 that Belgrade repudiate the union proved counter-productive; among other things, it transformed the Bulgarian union, which had been a matter of indifference to most Serbs, into the fetish (for a time at least) of Serbian national opinion.55 The general outlines of the 1906 crisis are set out in chapter 1, but one further point should be borne in mind, namely that what worried the politicians in Vienna was less the negligible commercial significance of the union with Bulgaria than the political logic underlying it. What if the Serbo-Bulgarian customs union were merely the first step in the direction of a ‘league’ of Balkan states hostile to Austria-Hungary and receptive to promptings from St Petersburg?

It is easy to write this off as Austrian paranoia, but in reality, the policy-makers in Vienna were not far off the mark: the Serbian-Bulgarian customs agreement was in fact the third of a sequence of secret alliances between Serbia and Bulgaria, of which the first two were already clearly anti-Austrian in orientation. A Treaty of Friendship and a Treaty of Alliance had already been signed in Belgrade on 12 May 1904 in circumstances of the strictest secrecy. Dumba had done his utmost to find out what was going on between the Bulgarian delegates visiting the city and their Serbian interlocutors, but though his suspicions were raised, he had failed to penetrate the curtain of confidentiality surrounding the negotiations. Vienna’s fear of Russian involvement, it turned out, was well founded. St Petersburg was indeed – notwithstanding the Austro-Russian détente and the immense effort of a disastrous war with Japan – working towards the creation of a Balkan alliance. A key figure in the negotiations was the Bulgarian diplomat Dimitar Rizov, sometime agent of the Russian Asiatic Department. On 15 September 1904 at eleven o’clock in the morning, the Russian ambassadors in Belgrade and Sofia were simultaneously (and secretly) presented with copies of the Serbian-Bulgarian Treaty of Alliance by the foreign ministers of Serbia and Bulgaria respectively.56

One difficult feature of Austro-Hungarian Balkan policy was the deepening interpenetration of foreign and domestic issues.57 For obvious reasons, domestic and international politics were most likely to become entangled in the case of those minorities for whom there existed an independent ‘motherland’ outside the boundaries of the empire. The Czechs, Slovenes, Poles, Slovaks and Croats of the Habsburg lands possessed no such sovereign external nation-state. The 3 million Romanians in the Duchy of Transylvania, on the other hand, did. Thanks to the intricacies of the dualist system, there was little Vienna could do to prevent oppressive Hungarian cultural policies from alienating the neighbouring kingdom of Romania, a political partner of great strategic value in the region. Yet it proved possible, at least until around 1910, to insulate Austro-Romanian relations from the impact of domestic tensions, mainly because the government of Romania, an ally of Austria and Germany, made no effort to foment or exploit ethnic discord in Transylvania.

The same could not be said, however, of the Serbs and the Kingdom of Serbia after 1903. Just over 40 per cent of the population of Bosnia-Herzegovina were Serbs, and there were large areas of Serbian settlement in the Vojvodina in southern Hungary and smaller ones in Croatia-Slavonia. After the regicide of 1903, Belgrade stepped up the pace of irredentist activity within the empire, focusing in particular on Bosnia-Herzegovina. In February 1906, the Austrian military attaché in Belgrade, Pomiankowski, summarized the problem in a letter to the chief of the General Staff. It was certain, Pomiankowski declared, that Serbia would number among the empire’s enemies in the event of a future military conflict. The problem was less the attitude of the government as such than the ultra-nationalist orientation of the political culture as a whole: even if a ‘sensible’ government were at the helm, Pomiankowski warned, it would be in no position to prevent the ‘all-powerful radical chauvinists’ from launching ‘an adventure’. More dangerous, however, than Serbia’s ‘open enmity and its miserable army’ was the ‘fifth-column work of the [Serbian] Radicals in peacetime, which systematically poisons the attitude of our South Slav population and could, if the worst came to the worst, create very serious difficulties for our army’.58

The ‘chauvinist’ irredentism of the Serbian state, or more precisely, of the most influential political forces within it, came to occupy a central place in Vienna’s assessments of the relationship with Belgrade. The official instructions composed in the summer of 1907 by Foreign Minister Count Alois von Aehrenthal for the new Austrian envoy to Serbia convey a sense of how relations had deteriorated since the regicide. Under King Milan, Aehrenthal recalled, the Serbian crown had been strong enough to counteract any ‘public Bosnian agitation’, but since the events of July 1903, everything had changed. It was not just that King Petar was politically too weak to oppose the forces of chauvinist nationalism, but rather that he had himself begun to exploit the national movement in order to consolidate his position. One of the ‘foremost tasks’ of the new Austrian minister in Belgrade would therefore be the close observation and analysis of Serbian nationalist activity. When the opportunity arose, the minister was to inform King Petar and Prime Minister Pašić that he was fully acquainted with the scope and character of pan-Serb nationalist activity; the leaders in Belgrade should be left in no doubt that Austria-Hungary regarded its occupation of Bosnia-Herzegovina as ‘definitive’. Above all, the minister was not to be put off by the usual official denials:

It is to be expected that they will respond to your well-meant warnings with the time-honoured cliché that the Serbian politicians always roll out when they are reproached with their furtive machinations vis-à-vis the occupied provinces: ‘The Serbian Government strives to maintain correct and blameless relations, but is in no position to hold back the sentiment of the nation, which demands action etc. etc.’59

Aehrenthal’s official instruction captures the salient features of Vienna’s attitude to Belgrade: a belief in the primordial power of Serbian nationalism, a visceral distrust of the leading statesmen, and a deepening anxiety over the future of Bosnia, concealed behind a pose of lofty and invulnerable superiority.

The scene was thus set for the annexation of Bosnia and Herzegovina in 1908. There had never been any doubt, either in Austria or in the chancelleries of the other great powers, that Vienna regarded the occupation of 1878 as permanent. In one of the secret articles of the renewed Three Emperors’ Alliance of 1881, Austria-Hungary had explicitly asserted the ‘right to annex these provinces at whatever moment she shall deem opportune’, and this claim was repeated at intervals in Austro-Russian diplomatic agreements. Nor was it contested in principle by Russia, though St Petersburg reserved the right to impose conditions when the moment for such a change of status arrived. The advantages to Austria-Hungary of a formal annexation were obvious enough. It would remove any doubt about the future of the provinces – a matter of some urgency, since the occupation statute agreed at the Congress of Berlin was due to expire in 1908. It would allow Bosnia and Herzegovina to be integrated more fully into the political fabric of the empire, through the establishment, for example, of a provincial parliament. It would create a more stable environment for inward investment. More importantly, it would signal to Belgrade (and to the Serbs in Bosnia-Herzegovina) the permanence of Austria-Hungary’s possession and thus, in theory at least, remove one incentive for further agitation.

Aehrenthal, who became foreign minister in November 1906, also had other reasons for pressing ahead. Until around the turn of the century, he had been a staunch supporter of the dualist system. But his faith in the Compromise was shaken in 1905 by the bitter infighting between the Austrian and Hungarian political elites over the administration of the joint armed forces. By 1907, he had come to favour a tripartite solution to the monarchy’s problems; the two dominant power-centres within the monarchy would be supplemented by a third entity incorporating the South Slavs (above all Croats, Slovenes and Serbs). This was a programme with a considerable following among the South Slav elites, especially the Croats, who resented being divided between Cisleithania, the Kingdom of Hungary and the province of Croatia-Slavonia, ruled from Budapest. Only if Bosnia-Herzegovina were fully annexed to the empire would it be possible eventually to incorporate it into the structure of a reformed trialist monarchy. And this in turn – such was Aehrenthal’s devout hope – would provide an internal counterweight to the irredentist activities of Belgrade. Far from being the ‘Piedmont’ of South Slavdom in the Balkans, Serbia would become the severed limb of a vast, Croat-dominated South Slav entity within the empire.60

The clinching argument for annexation was the Young Turk revolution that broke out in Ottoman Macedonia in the summer of 1908. The Young Turks forced the Sultan in Constantinople to proclaim a constitution and the establishment of a parliament. They planned to subject the Ottoman imperial system to a root-and-branch reform. Rumours circulated to the effect that the new Turkish leadership would shortly call general elections throughout the Ottoman Empire, including the areas occupied by Austria-Hungary, which currently possessed no representative organs of their own. What if the new Turkish administration, its legitimacy and confidence enhanced by the revolution, were to demand the return of its lost western salient and to woo its inhabitants with the promise of constitutional reform?61 Hoping to capitalize on these uncertainties, an opportunist Muslim–Serb coalition emerged in Bosnia calling for autonomy under Turkish suzerainty.62 There was now the danger that an ethnic alliance within the province might join forces with the Turks to push the Austrians out.

In order to forestall any such complications, Aehrenthal moved quickly to prepare the ground for annexation. The Ottomans were bought out of their nominal sovereignty with a handsome indemnity. Much more important were the Russians, upon whose acquiescence the whole project depended. Aehrenthal was a firm believer in the importance of good relations with Russia – as Austrian ambassador in St Petersburg during the years 1899–1906, he had helped to consolidate the Austro-Russian rapprochement. Securing the agreement of the Russian foreign minister, Alexandr Izvolsky, was easy. The Russians had no objection to the formalization of Austria-Hungary’s status in Bosnia-Herzegovina, provided St Petersburg received something in return. Indeed it was Izvolsky, with the support of Tsar Nicholas II, who proposed that the annexation of Bosnia-Herzegovina be exchanged for Austrian support for improved Russian access to the Turkish Straits. On 16 September 1908, Izvolsky and Aehrenthal clarifed the terms of the deal at Schloss Buchlau, the Moravian estate of Leopold von Berchtold, Austro-Hungarian ambassador in St Petersburg. In a sense, therefore, the annexation of 1908 was born out of the spirit of the Austro-Russian Balkan entente. There was, moreover, a neat symmetry about the exchange, since Izvolsky and Aehrenthal were essentially after the same thing: gains that would be secured through secret negotiations at the expense of the Ottoman Empire and in contravention of the Treaty of Berlin.63

Despite these preparations, Aehrenthal’s announcement of the annexation on 5 October 1908 triggered a major European crisis. Izvolsky denied having reached any agreement with Aehrenthal. He subsequently even denied that he had been advised in advance of Aehrenthal’s intentions, and demanded that an international conference be convened to clarify the status of Bosnia-Herzegovina.64 The resulting crisis dragged on for months as Serbia, Russia and Austria mobilized and counter-mobilized and Aehrenthal continued to evade Izvolsky’s call for a conference that had not been foreseen in the agreement at Buchlau. The issue was resolved only by the ‘St Petersburg note’ of March 1909, in which the Germans demanded that the Russians at last recognize the annexation and urge Serbia to do likewise. If they did not, Chancellor Bülow warned, then things would ‘take their course’. This formulation hinted not just at the possibility of an Austrian war on Serbia, but, more importantly, at the possibility that the Germans would release the documents proving Izvolsky’s complicity in the original annexation deal. Izvolsky immediately backed down.

Aehrenthal has traditionally carried the lion’s share of the responsibility for the annexation crisis. Is this fair? To be sure, the Austrian foreign minister’s manoeuvres lacked diplomatic transparency. He chose to operate with the tools of the old diplomacy: confidential meetings, the exchange of pledges, and secret bilateral agreements, rather than attempting to resolve the annexation issue through an international conference involving all the signatories of the Treaty of Berlin. This preference for furtive arrangements made it easier for Izvolsky to claim that he, and by extension Russia, had been hoodwinked by the ‘slippery’ Austrian minister. Yet the evidence suggests that the crisis took the course that it did because Izvolsky lied in the most extravagant fashion in order to save his job and reputation. The Russian foreign minister had made two serious errors of judgement. He had assumed, firstly, that London would support his demand for the opening of the Turkish Straits to Russian warships. He had also grossly underestimated the impact of the annexation on Russian nationalist opinion. According to one account, he was initially perfectly calm when news of the annexation reached him in Paris on 8 October 1908. It was only during his stay in London a few days later, when the British proved uncooperative and he got wind of the press response in St Petersburg, that he realized his error, panicked, and began to construct himself as Aehrenthal’s dupe.65

Whatever the rights and wrongs of Aehrenthal’s policy, the Bosnian annexation crisis was a turning point in Balkan geopolitics. It devastated what remained of Austro-Russian readiness to collaborate on resolving Balkan questions; from this moment onwards, it would be much more difficult to contain the negative energies generated by conflicts among the Balkan states. It also alienated Austria’s neighbour and ally, the Kingdom of Italy. There had long been latent tensions between the two states – Italian minority rights in Dalmatia and Croatia-Slavonia and power-political rivalry in the Adriatic were the two most important bones of contention – but the annexation crisis prompted calls for Italian compensation and kindled Italian resentments to a new pitch of intensity. In the last years before the outbreak of war, it became increasingly difficult to reconcile Italian and Austrian objectives on the Balkan Adriatic coast.66 The Germans were initially noncommittal on the annexation question, but they soon rallied energetically to Austria-Hungary’s support, and this, too, was an ambivalent development. It had the desired effect of dissuading the Russian government from attempting to extract further capital out of the annexation crisis, but in the longer run, it reinforced the sense in both St Petersburg and London that Austria was the satellite of Berlin – a perception that would play a dangerous role in the crisis of 1914.

In Russia, the impact of the crisis was especially deep and lasting. Defeat in the war with Japan in 1904–5 had shut off the prospect of far eastern expansion for the foreseeable future. The Anglo-Russian Convention signed by Izvolsky and the British ambassador Sir Arthur Nicolson on 31 August 1907 had established the limits of Russian influence in Persia, Afghanistan and Tibet. The Balkans remained (for the moment) the only arena in which Russia could still pursue a policy focused on projecting imperial power.67 Intense public emotions were invested in Russia’s status as protector of the lesser Slavic peoples, and underlying these in the minds of the key decision-makers was a deepening preoccupation with the question of access to the Turkish Straits. Misled by Izvolsky and fired up by chauvinist popular emotion, the Russian government and public opinion interpreted the annexation as a brutal betrayal of the understanding between the two powers, an unforgivable humiliation and an unacceptable provocation in a sphere of vital interest. In the years that followed the Bosnian crisis, the Russians launched a programme of military investment so substantial that it triggered a European arms race.68 There were also signs of a deeper Russian political involvement with Serbia. In the autumn of 1909, the Russian foreign ministry appointed Nikolai Hartwig, a ‘fiery fanatic in the old slavophile tradition’, to the Russian embassy in Belgrade. Once in office, Hartwig, an energetic and intelligent envoy, worked hard to push Belgrade into taking up a more assertive position against Vienna. Indeed, he pushed so hard in this direction that he sometimes exceeded the instructions of his managers in St Petersburg.69

The annexation crisis also further poisoned relations between Vienna and Belgrade. As so often, the situation was exacerbated by political conditions inside the dual monarchy. For several years, the Austro-Hungarian authorities had been observing the activities of the Serbo-Croat coalition, a political faction that emerged within the Croatian Diet at Agram (today, Zagreb), capital of Hungarian-ruled Croatia-Slavonia, in 1905. After the diet elections of 1906, the coalition secured control of the Agram administration, embraced a ‘Yugoslav’ agenda seeking a closer union of the South Slav peoples within the empire, and fought long battles with the Hungarian authorities over such ticklish issues as the requirement that all state railway officials should be able to speak Magyar. There was nothing especially unusual about this constellation; what worried the Austrians was the suspicion that some or all of the deputies of the coalition might be operating as a fifth column for Belgrade.70

During the crisis of 1908–9, these apprehensions escalated to the point of paranoia. In March 1909, just as Russia was backing down from a confrontation over Bosnia, the Habsburg administration launched an astonishingly inept judicial assault on the Serbo-Croat coalition, charging fifty-three mainly Serb activists with treason for plotting to detach the South Slav lands from Austria-Hungary and join them to Serbia. At around the same time, the Vienna-based historian and writer Dr Heinrich Friedjung published an article in the Neue Freie Presse accusing three prominent coalition politicians of receiving subsidies from Belgrade in return for treasonous activity on behalf of the Kingdom of Serbia. Friedjung claimed to have been shown confidential government documents demonstrating beyond doubt the truth of these charges.

The treason trial at Agram dragged on from 3 March until 5 November 1909 and quickly collapsed into an unmitigated public relations disaster for the government. The court heard 276 witnesses for the prosecution, but none who had been nominated by the defence. All thirty-one convictions handed down in Agram were subsequently quashed on appeal in Vienna. At the same time, a chain of libel trials against Friedjung and the editor of the Reichspost, which had reprinted his claims, revealed further embarrassing manipulations. The ‘secret documents’ on which the good doctor had based his charges turned out to be forgeries passed to the Austrian legation in Belgrade by a shady Serbian double agent, and supplied in turn to Friedjung by the foreign ministry in Vienna. The unfortunate Friedjung, whose excellent reputation as an historian had been shamefully misused, apologized and withdrew his accusations. But the tireless Czech national activist and advocate for the accused, Tomáš Masaryk, continued to pursue the matter at the highest level, searching far and wide (including in Belgrade) for new evidence and claiming in various public forums that the Austrian ambassador in Belgrade had knowingly procured the forgeries on Count Aehrenthal’s behalf.71

It is highly unlikely that the authorities in Vienna knew from the outset that the documents were inauthentic. Paranoia probably engendered credulity; the Austrians were primed to believe what they feared to find. But the Agram and Friedjung trials imposed a lasting burden on relations between Vienna and Belgrade. Particularly awkward was the fact that the scandal soon began to focus on the Austrian representative in Serbia, Johann Count Forgách von Ghymes and Gács, with far-reaching consequences for the diplomatic relationship between the two countries. Throughout 1910 and 1911, the Masaryk campaign continued to produce new and embarrassing ‘revelations’ of Austrian perfidy (not all of which were true). The Serbian press rejoiced and there were loud demands for Forgách’s recall from Belgrade.72 But Forgách, who had long since ceased to take any pleasure whatsoever in his posting, vigorously (and probably truthfully) denied all charges and Aehrenthal, who was himself under attack, felt unable to remove the embattled envoy for as long as this might imply an acknowledgement from Vienna that the Austrian authorities had deliberately deceived the public. ‘The situation is not pleasant for me,’ Forgách wrote in a private letter to the Foreign Office section chief in Vienna in November 1910, ‘but I will survive the Belgrade newspaper storms – as I have survived so much else – provided the government here behaves in a halfway decent fashion.’73

What especially infuriated Forgách was the continuing involvement of senior Serbian officials – foremost among them the Foreign Office section chief Miroslav Spalajković – in the campaign to discredit him. Spalajković provided Masaryk with evidence against the Austrian government; he was even called as an expert witness on behalf of the Serbo-Croat coalition during the Friedjung trials. Having helped to explode the credibility of the forged documents, Spalajković went a step further and asserted that Forgách had deliberately secured them, in the hope of trumping up charges against the Serbo-Croat coalition. In the winter of 1910–11, the Dutch envoy in Belgrade, Vredenburch, reported that Spalajković continued to disseminate rumours against the Austrian representative across the diplomatic community.74 To make matters worse, Spalajković and his wife were constantly to be seen in the company of Hartwig, the new Russian minister; indeed it was said that the couple virtually lived at the Russian mission.75 Forgách became unhealthily obsessed with the man he called ‘our deadly enemy’; an exchange of curt letters between the envoy and the official further poisoned relations between them, and by April 1911 Forgách had ordered all personnel at the Austrian legation in Belgrade to avoid contact of any kind with Spalajković. ‘This constantly overwrought man,’ he informed Aehrenthal, ‘is in some respects not entirely sane. Since the annexation, his hatred for the [Austro-Hungarian] Monarchy has developed almost into a mental illness.’76

Forgách’s position in Belgrade had clearly become untenable, and he was recalled in the summer of 1911. But the scandal of the Agram– Friedjung trials and their aftermath in the Serbian capital are worth recalling, because they involved individuals who would figure prominently in the events of 1914. Miroslav Spalajković was a very senior foreign policy official with a long-standing interest in Bosnia-Herzegovina – his wife was a Bosnian and he had composed a doctoral thesis at the University of Paris in 1897 arguing that, as the two provinces remained autonomous legal entities under Ottoman suzerainty, their annexation by Austria-Hungary could never be legitimate.77 He subsequently served as the Serbian minister in Sofia, where he played an important role – in collusion with the Russians – in forging the Serbian-Bulgarian alliance at the centre of the Balkan League that launched the First Balkan War in 1912. During his posting at Sofia he remained Nikolai Hartwig’s most intimate friend, visiting him in Belgrade ‘up to twenty times a month’.78 He was subsequently transferred to the even more important legation in St Petersburg. Here his task would be to interpret the intentions of the Tsar and his ministers to the Serbian government in Belgrade as the crisis of July 1914 unfolded. Forgách, too, who left his posting as a staunch Serbophobe, remained on the scene as one of the leading figures in a cohort of officials who helped shape the policies of the Austro-Hungarian foreign ministry after the sudden death of Aehrenthal from leukaemia in 1912.79 And we should not forget the bitter personal animosity between Izvolsky and Aehrenthal, which was rightly identified by the Vienna quality press in the aftermath of the Bosnian crisis as an impediment to the improvement of relations between Austria-Hungary and Russia.80 It is a curious feature of the July Crisis of 1914 that so many of the key actors in it had known each other for so long. Beneath the surface of many of the key transactions lurked personal antipathies and long-remembered injuries.

The Serbian problem was not a matter that the Austrians could handle in isolation. It was embedded within a complex of interlocked questions. First there was the pressing issue of Serbia’s relationship with Russia, which was closer after the annexation crisis than it had been before. Vienna was deeply suspicious of the Russian minister Hartwig, whose Austrophobia, pan-Slavism and growing influence in Belgrade augured ill for the future. Hartwig, the French minister in Sofia reported, was ‘the archetype of the true Muzhik’, a partisan of the ‘old Russian Turkish policy’ who was prepared to ‘sacrifice the Far East for the Balkans’.81 Hartwig established relations of extraordinary intimacy with Prime Minister Nikola Pašić. The two men met almost daily – ‘your beard is consulting with our beard’, the officials of the Serbian foreign ministry would comment to the junior diplomats of the Russian mission. ‘No one,’ a Russian staffer commented, ‘believed that secrets were possible in relation to the political goals shared by [Russia and Serbia].’82 The Russian minister was greeted everywhere in Belgrade like a conquering hero: ‘people just needed to see his characteristic head and he would get standing ovations’.83

Vienna could in theory offset Serbian hostility by seeking better relations with Bulgaria. But pursuing this option also entailed difficulties. Since there was still a bitter dispute over the border between Bulgaria and Romania, cosying up to Sofia brought the risk of alienating Bucharest. A hostile Bucharest was extremely undesirable because of the huge Romanian minority in Hungarian Transylvania. If Romania were to turn away from Vienna towards St Petersburg, the minority issue might well become a question of regional security. Hungarian diplomats and political leaders in particular warned that ‘Greater Romania’ posed as serious a threat to the dual monarchy as ‘Greater Serbia’.

A further concern was the little principality of Montenegro on the Adriatic coast. This picturesque, impoverished kingdom provided the backdrop for Franz Lehár’s The Merry Widow, where it appeared thinly disguised as the ‘Grand Duchy of Pontevedro’ (the German libretto gave the game away by explicitly stating that the singers should wear ‘Montenegrin national costume’).84 Montenegro was the smallest of the Balkan states, with a population of only 250,000 scattered across a beautiful but unforgiving terrain of black peaks and plunging ravines. This was a country where the king, dressed in a splendid uniform of gold, silver, red and blue, could be seen smoking at dusk in front of his palace, hoping to chat with a passer-by. When the Prague journalist Egon Erwin Kisch travelled by foot from Cetinje, then the capital of Montenegro, to the beautiful port city of Rijeka (now in Croatia) in the summer of 1913, he was disconcerted to hear gunshots ringing out across the valleys. He wondered at first whether a Balkan war had broken out, but his guard assured him that it was just the Montenegrin youth with their Russian rifles shooting small fish in the fast-flowing mountain streams.85

Though poor and tiny, Montenegro was not unimportant. Its mountain guns on the Lovčen heights overlooked the indefensible Austrian harbour facilities at Cattaro on the Adriatic, to the vexation of Habsburg naval planners. Nikola, the reigning prince since 1861 and thus the third-longest-serving European monarch after Queen Victoria and Franz Joseph, was extraordinarily ambitious. He had succeeded in doubling the territory of his kingdom at the Berlin Congress of 1878, expanded it again during the annexation crisis of 1908, and thereafter had his eye on a piece of northern Albania. He elevated himself to the status of king in 1910. He also married off his female offspring with quite extraordinary skill. King Petar Karadjordjević of Serbia was his son-in-law (though his Montenegrin wife had died by the time Petar was crowned); another of Nikola’s daughters, Elena, married Victor Emmanuel III of Italy (king from 1900); two others married Russian archdukes in St Petersburg, where they became prominent figures in Russian high society. Nikola exploited his strategically sensitive position in order to attract funding from powerful foreign sponsors, most importantly Russia. In 1904, he demonstrated his solidarity with the great Slav ally by solemnly declaring war on Japan. The Russians reciprocated with military subsidies and a military mission whose task was the ‘reorganisation of the Montenegrin army’.86

Italy, linked through its royal house with Montenegro, was a further complication. Italy had been a member of the Triple Alliance with Austria and Germany since May 1882 and renewed its membership in 1891, 1902 and 1912. But public sentiment on the question of relations with Austria was deeply divided. Broadly speaking, liberal, secular, nationalist Italy tended to favour a policy of confrontation with Austrians, especially in the Adriatic, which Italian nationalists regarded as a natural avenue for the consolidation of Italian influence. Catholic, clerical, conservative Italy tended by contrast to favour a policy of rapprochement and collaboration with Vienna. Reflecting these divided loyalties, Rome operated an elaborate, multi-layered and often contradictory diplomacy. In 1900 and 1902, the Italian government signed secret agreements with France that cancelled out most of its treaty obligations to Vienna and Berlin. From 1904, moreover, the Italians made it increasingly clear that they viewed Austro-Hungarian policy in the Balkans as impinging on their interests in the area. Montenegro was seen as a promising field for the expansion of Italian commercial and cultural influence in the Balkans and Foreign Minister Tomaso Tittoni cultivated very friendly relations with Belgrade and Sofia.87

The Italians reacted sharply to the annexation of Bosnia in 1908, less because they objected in principle to the Austrian move than because Aehrenthal refused to compensate Rome with the foundation of an Italian university in the mainly Italian-speaking Habsburg port of Trieste.88 In October 1909, King Victor Emmanuel III broke ranks with the Triple Alliance to sign a secret agreement with Tsar Nicholas II. The ‘Racconigi Bargain’, as it later became known, stipulated that Italy and Russia would not conclude agreements on the ‘European East’ without each other’s consent and that the two powers pledged ‘to regard with benevolence, the one Russia’s interests in the matter of the Straits, the other Italian interests in Tripoli and Cyrenaica’.89 The agreement was less momentous than it seemed, for the Italians soon after signed an understanding with Vienna that largely cancelled out the pledges of Racconigi, but it signalled Rome’s determination to pursue a more assertive and independent policy.

The likeliest apple of future Austro-Italian discord in the Balkans was Albania, still locked within the Ottoman Empire, which both Italy and Austria viewed as falling within their sphere of influence. Since the 1850s, Austria had, through its vice-consulate in Skutari, exercised a kind of religious protectorate over the Catholics in the north of the country. But the Italians, too, took a strong interest in Albania with its long Adriatic coastline. By the turn of the century, Rome and Vienna had agreed that they would support Albanian independence in the event of a collapse of Ottoman power in the region. The question of how exactly influence would be shared between the two Adriatic powers remained unresolved.

In March 1909, Serbia formally pledged that it would desist from further covert operations against Austrian territory and maintain good neighbourly relations with the empire. In 1910, Vienna and Belgrade even agreed, after much wrangling, a trade treaty ending the Austro-Serbian commercial conflict. A 24 per cent rise in Serbian imports during that year bore witness to improving economic conditions. Austro-Hungarian goods began to reappear on the shelves of shops in Belgrade, and by 1912, the dual monarchy was once again the main buyer and supplier of Serbia.90 At meetings between Pašić and the Austrian representative, there were assurances of goodwill on both sides. But a deep awkwardness had settled over the two states’ relations that seemed impossible to dispel. Although there was talk of an official visit by King Petar to Vienna, it never materialized. On the initially genuine pretext of the monarch’s ill health, the Serbian government moved the visit from Vienna to Budapest, then postponed it, and then, in April 1911, put it off indefinitely. Yet, to the chagrin of the Austrians, there was a highly successful royal trip to Paris in the winter of 1911. The French visit was deemed so important that the Serbian envoy in Paris returned to Belgrade to help prepare it. An earlier plan to combine the journey to France with stops in Vienna and Rome was jettisoned. Petar arrived in Paris on 16 November and was accommodated in the court of the Quay d’Orsay, where he was welcomed by the president of the republic and presented with a gold medal, fashioned especially for the occasion, commemorating the king’s service, as a young Serbian exile and volunteer, in the French war of 1870 against Prussia. At a state dinner on the same evening – and to the intense annoyance of the Austrians – President Fallières opened his speech by hailing Petar as ‘the King of all the Serbs’ (including, implicitly, those living within the Austro-Hungarian Empire) and ‘the man who was going to lead his country and people into freedom’. ‘Visibly excited’, Petar replied that he and his fellow Serbs would count on France in their fight for freedom.91

Behind the scenes, moreover, the work to redeem Bosnia-Herzegovina for Serbdom continued. Narodna Odbrana, ostensibly converted into a purely cultural organization, soon resumed its former activities; its branch organizations proliferated after 1909 and spilled over into Bosnia-Herzegovina. The Austrians monitored – as far as they were able – the espionage activity of Serbian agents crossing the border. A characteristic example was a certain Dragomir Djordjević, a reserve lieutenant in the Serbian army who combined his cultural work as an ‘actor’ in Bosnia with the management of a covert network of Serb informants; he was spotted returning to Serbia for weapons training in October 1910.92 Austrian representatives in Serbia were also aware from an early stage of the existence of Ujedinjenje ili smrt!, though they were at first unsure of what they should make of this mysterious newcomer to the Belgrade scene. In a report filed on 12 November 1911, the new minister in Belgrade (Forgách’s successor), Stephan von Ugron zu Abránfalva, notified Vienna of the existence of ‘an association supposedly existing in officer circles’ that was currently the subject of press comment in Serbia. At this point, ‘nothing positive’ was known about the group, save that it called itself the Black Hand and was chiefly concerned with regaining the influence over national politics that the army had enjoyed in the Obrenović era.

Further reports from Ugron and the Austrian military attaché Otto Gellinek fleshed out the picture somewhat. Apis was now identified as the dominant figure in the new network and a more elaborate picture emerged of its objectives: ‘The programme of the movement consists in the removal of all personalities in the country who stand in the way of the Greater-Serbian idea’ and the enthronement of a leader ‘who will be ready to lead the fight for the unification of all Serbs’.93 Press rumours to the effect that the Black Hand had drawn up a hit-list of politicians to be assassinated in the event of a coup against the current Radical government, nourished by the mysterious murders of two prominent opposition politicians in the autumn of 1911, were later discounted as false. It appeared, Gellinek reported on 22 November 1911, that the conspirators planned to use legal means to remove the ‘inner enemies of Serbdom’, in order then to ‘turn with unified force against its external foes’.94

The Austrians initially viewed these developments with surprising equanimity. It was virtually impossible, Gellinek observed, to keep any organization in Serbia secret for long ‘because for every five conspirators, there is one informant’. Conspiracies were nothing new in Serbia, after all; the matter was therefore of little importance.95 But the attitude of the Austrian observers changed as they began to grasp the extent of the Black Hand’s influence over parts of the state apparatus. In December 1911, the military attaché reported that the Serbian minister of war had called off an investigation into the movement ‘because there would otherwise be difficulties of far-reaching significance’. Early in February 1912, he observed that the network had acquired semi-official character; it appeared that the government was ‘fully informed on all members [of the Black Hand] and on their activity’; the fact that Minister of War Stepanović, a protector of the organization, remained in office was a sign of its growing political influence.96

A complex picture emerged that would shape Austrian behaviour in the summer of 1914. It was clear on the one hand that Unity or Death! was a subversive network genuinely opposed to and feared by the current civilian authorities in the Kingdom of Serbia. But it was also the case that the great-Serbian objectives of the network were widely condoned and supported, both by elements of the civilian leadership and by the broader public in Serbia. More importantly, there were times when the movement and the administration appeared to operate in tandem. In February 1912, Ugron warned that the Serbian authorities might collaborate with ‘an enthusiastic military-patriotic movement’, provided its energies could be turned outwards against Serbia’s external foes and away from subversive activity within the kingdom itself.97 The irredentist organ Pijemont openly espoused anti-Habsburg ultra-nationalist objectives – by defining itself thus in terms of ‘national’ goals, Ugron noted, the Black Hand made it difficult for the Serbian civilian authorites to take action against it.98 In short, the Austrians grasped both the extent of Black Hand influence and the complexity of the constraints preventing the Pašić government from taking action to counter it.

The outlines of this analysis remained in place until the summer of 1914. The Austrians followed as closely as they could the dramatic growth of the network during the Balkan Wars of 1912 and 1913. In January 1914, attention focused on the trial of a regicide officer by the name of Vemić, who had been notorious in 1903 for carrying about with him in a suitcase a desiccated flap of flesh that he had cut from one of Queen Draga’s breasts as a trophy of the night of 11 June. In October 1913, during the Second Balkan War, Vemić shot dead a Serbian recruit for being too slow to follow an order and was tried by a military tribunal. His acquittal by a court staffed entirely by senior officers triggered uproar in parts of the Belgrade press and Vemić was called for a retrial before the Serbian Supreme Court. But his sentence – a mere ten months of imprisonment – was cut short by a royal pardon, extracted by the military leadership from the king at the end of December 1913.99 The officer corps is ‘a politically decisive factor in today’s Serbia’, Gellinek noted in May 1914. This growth in the ‘praetorian element’ in Serbian public life in turn represented an enhanced threat to Austria-Hungary, since ‘the officer corps is also the bastion of the great-Serbian, extreme Austrophobe tendency’.100