In a cartoon published in the late 1890s, a French artist depicted the crisis brewing over China on the eve of the Boxer Uprising. Watched warily by Britain and Russia, Germany makes to carve out a slice identified as ‘Kiao-Tschaou’ from a pie called ‘China’, while France offers her Russian ally moral support and Japan looks on. Behind them all, a Qing official throws up his hands in despair, but is powerless to intervene. As so often in such images, the powers are represented as individual persons: Britain, Germany and Russia by caricatures of their respective sovereigns, France by ‘Marianne’, the personification of the Republic, and Japan and China by stereotypical exotic figures. Personifying states as individuals was part of the shorthand of European political caricature, but it also reflects a deep habit of thought: the tendency to conceptualize states as composite individuals governed by compact executive agencies animated by an indivisible will.

Yet even a very cursory look at the governments of early twentieth-century Europe reveals that the executive structures from which policies emerged were far from unified. Policy-making was not the prerogative of single sovereign individuals. Initiatives with a bearing on the course of a country’s policy could and did emanate from quite peripheral locations in the political structure. Factional alignments, functional frictions within government, economic or financial constraints and the volatile chemistry of public opinion all exerted a constantly varying pressure on decision-making processes. As the power to shape decisions shifted from one node in the executive structure to another, there were corresponding oscillations in the tone and orientation of policy. This chaos of competing voices is crucial to understanding the periodic agitations of the European system during the last pre-war years. It also helps to explain why the July Crisis of 1914 became the most complex and opaque political crisis of modern times.

‘The Scramble for China’, by Henri Meyer, Le Petit Journal, 1898

Early twentieth-century Europe was a continent of monarchies. Of the six most important powers, five were monarchies of one kind or another; only one (France) was a republic. The relatively new nation-states of the Balkan peninsula – Greece, Serbia, Montenegro, Bulgaria, Romania and Albania – were all monarchies. The Europe of fast cruisers, radio-telegraph, and electric cigar-lighters still carried at its heart this ancient, glittering institution yoking large and complex states to the vagaries of human biology. The European executives were still centred on the thrones and the men or women who sat on them. Ministers in Germany, Austria-Hungary and Russia were imperial appointees. The three emperors had unlimited access to state papers. They also exercised formal authority over their respective armed forces. Dynastic institutions and networks structured the communications between states. Ambassadors presented their credentials to the sovereign in person and direct communications and meetings between monarchs continued to take place throughout the pre-war years; indeed they acquired a heightened importance, creating a parallel plane of interaction whose relationship to official diplomacy was sometimes difficult to ascertain.

Monarchs were symbolic as well as political actors, and in this role they could capture and focus collective emotions and associations. When Parisian onlookers gawped at Edward VII sprawled in a chair outside his hotel smoking a cigar, they felt they were looking at England in the form of a very fat, fashionable and confident man. His triumphant ascent in Parisian public opinion in 1903 helped smooth the path to the Entente signed with France in the following year. Even the mild-mannered despot Nicholas II was greeted like a conquering hero by the French when he visited Paris in 1896, despite his autocratic political philosophy and negligible charisma, because he was seen as the personification of the Franco-Russian Alliance.1 And who embodied the most unsettling aspects of German foreign policy – its vacillations, lack of focus and frustrated ambition – better than the febrile, tactless, panic-prone, overbearing Kaiser Wilhelm, the man who dared to advise Edvard Grieg on how to conduct Peer Gynt?2 Whether or not the Kaiser actually made German policy, he certainly symbolized it for Germany’s opponents.

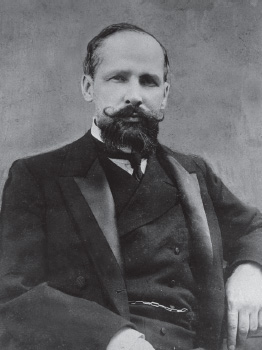

Wilhelm II and Nicholas II wearing the uniforms of each other’s countries

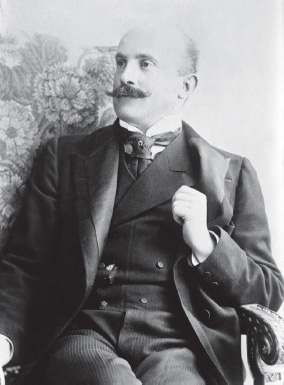

Edward VII in his uniform as colonel of the Austrian 12th Hussars

At the core of the monarchical club that reigned over pre-war Europe was the trio of imperial cousins: Tsar Nicholas II, Kaiser Wilhelm II and George V. By the turn of the twentieth century, the genealogical web of Europe’s reigning families had thickened almost to the point of fusion. Kaiser Wilhelm II and King George V were both grandsons of Queen Victoria. Tsar Nicholas II’s wife, Alexandra of Hesse-Darmstadt, was Victoria’s granddaughter. The mothers of George V and Nicholas II were sisters from the house of Denmark. Kaiser Wilhelm and Tsar Nicholas II were both great-great grandsons of Tsar Paul I. The Kaiser’s great-aunt, Charlotte of Prussia, was the Tsar’s grandmother. Viewed from this perspective, the outbreak of war in 1914 looks rather like the culmination of a family feud.

Assessing how much influence these monarchs wielded over or within their respective executives is difficult. Britain, Germany and Russia represented three very different kinds of monarchy. Russia’s was, in theory at least, an autocracy in which the parliamentary and constitutional restraints on the monarch’s authority were weak. Edward VII and George V were constitutional and parliamentary monarchs with no direct access to the levers of power. Kaiser Wilhelm II was something in between – in Germany, a constitutional and parliamentary system was grafted on to elements of the old Prussian military monarchy that had survived the process of national unification. But the formal structures of governance were not necessarily the most significant determinants of monarchical influence. Other important variables included the determination, competence and intellectual grasp of the monarch himself, the ability of ministers to block unwelcome initiatives and the extent of agreement between monarchs and their governments.

One of the most striking features of the influence wielded by the sovereigns on the formulation of foreign policy is its variation over time. Edward VII, who presided over the diplomatic realignments of 1904–7, had strong views on foreign policy and prided himself on being well informed. His attitudes were those of an imperialist ‘jingo’; he was infuriated by Liberal opposition to the Afghan War of 1878–9, for example, and told the colonial administrator Sir Henry Bartle Frere: ‘If I had my way I should not be content until we had taken the whole of Afghanistan and kept it.’3 He was overjoyed at the news of the raid against the Transvaal Republic in 1895, supportive of Cecil Rhodes’s involvement in it, and infuriated by the Kaiser’s Kruger telegram. Throughout his adult life he maintained a determined hostility to Germany. The roots of this antipathy appear to have lain partly in his opposition to his mother, Queen Victoria, whom he regarded as excessively friendly to Prussia, and partly in his fear and loathing of Baron Stockmar, the unsmiling Germanic pedagogue appointed by Victoria and Albert to hold the young Edward to a regime of unstinting study. The Prussian-Danish War of 1864 was a formative episode in his early political life – Edward’s sympathies in that conflict rested firmly with the Danish relatives of his new bride.4 After his accession to the throne, Edward was an important sponsor of the anti-German group of policy-makers around Sir Francis Bertie.5

The king’s influence reached its height in 1903, when an official visit to Paris – ‘the most important royal visit in modern history’, as it has been called – paved the road towards the Entente between the two imperial rivals. Relations between the two western empires were still soured at this time by French outrage over the Boer War. The visit, which had been organized on Edward’s own initiative, was a public relations triumph and did much to clear the air.6 After the Entente had been signed, Edward continued to work towards an agreement with Russia, even though, like many of his countrymen, he detested the tsarist political system and remained suspicious of the designs that Russia had on Persia, Afghanistan and northern India. In 1906, when he heard that the Russian foreign minister Izvolsky was in Paris, he rushed south from Scotland in the hope that a meeting could be set up. Izvolsky responded in kind and made the journey to London, where the two men met for talks that – according to Charles Hardinge – ‘helped materially to smooth the path of the negotiations then in progress for an agreement with Russia’.7 In both these instances, the king was not deploying executive powers as such, but acting as a kind of supernumerary ambassador. He could do this because his priorities accorded closely with those of the liberal imperialist faction at Whitehall, whose dominance in foreign policy he had himself helped to reinforce.

George V was a very different case. Until his accession in 1910, he took little interest in foreign affairs and had acquired only the sketchiest sense of Britain’s relations with other powers. The Austrian ambassador Count Mensdorff was delighted with the new king, who seemed, by contrast with his father, to be innocent of strong biases for or against any foreign state.8 If Mensdorff hoped the changing of the guard would produce an attenuation of the anti-German theme in British policy, he was soon to be disappointed. In foreign policy, the new monarch’s seeming neutrality merely meant that policy remained firmly in the hands of the liberal imperialists around Grey. George never acquired a political network to rival his father’s, refrained from backstairs intrigue and avoided expounding policy without the explicit permission of his ministers.9 He was in more or less constant communication with Edward Grey and granted the foreign secretary frequent audiences whenever he was in London. He was scrupulous about seeking Grey’s approval for the content of political conversations with foreign representatives – especially his German relatives.10 George’s accession to the throne thus resulted in a sharp decline in the crown’s influence on the general orientation of foreign policy, even though the two monarchs wielded identical constitutional powers.

Even within the highly authoritarian setting of the Russian autocracy, the influence of the Tsar over foreign policy was subject to narrow constraints and waxed and waned over time. Like George V, the new Tsar was a blank sheet of paper when he came to the throne in 1894. He had not created a political network of his own before the accession and his deference to his father ensured that he refrained from expressing a view on government policy. As an adolescent, he had shown little aptitude for the study of affairs of state. Konstantin Pobedonostsev, the conservative jurist drafted in to give the teenage Nicky a master class on the inner workings of the tsarist state, later recalled: ‘I could only observe that he was completely absorbed in picking his nose.’11 Even after he mounted the throne, extreme shyness and terror at the prospect of having to wield real authority prevented him in the early years from imposing his political preferences – insofar as he had them – on the government. He lacked, moreover, the kind of executive support he would have needed to shape the course of policy in a consistent way. He possessed, for example, no personal secretariat and no personal secretary. He could – and did – insist on being informed of even quite minor ministerial decisions, but in a state as vast as Russia’s, this merely meant that the monarch was engulfed in trivia while matters of real import fell by the wayside.12

The Tsar was nonetheless able, especially from around 1900, to impart a certain direction to Russian foreign policy. By the late 1890s, Russia was deeply involved in the economic penetration of China. Not everyone in the administration was happy with the Far Eastern policy. Some resented the immense cost of the infrastructural and military commitments involved. Others, such as the minister of war, General Aleksei A. Kuropatkin, viewed the Far East as a distraction from more pressing concerns on the western periphery, especially the Balkans and the Turkish Straits. But at this time Nicholas II still firmly believed that the future of Russia lay in Siberia and the Far East and ensured that the exponents of the Eastern policy prevailed over their opponents. Despite some initial misgivings, he supported the policy of seizing the Chinese bridgehead at Port Arthur (today Lüshun) on the Liaodong peninsula in 1898. In Korea, Nicholas came to support a policy of Russian penetration that placed St Petersburg on a collision course with Tokyo.

Nicholas’s interventions took the form of informal alignments, rather than of executive decisions. He was closely associated, for example, with the aristocratic entrepreneurs who ran the vast Yalu river timber concession in Korea. The Yalu timber magnate A. M. Bezobrazov, a former officer of the elite Chevaliers Guards, used his personal connection with the Tsar to establish the Yalu as a platform for extending Russian informal empire on the Korean peninsula. In 1901, the finance minister Sergei Witte reported that Bezobrazov was with the Tsar ‘no less than two times a week – for hours at a time’ advising him on Far Eastern policy.13 Ministers were exasperated by the presence at court of these influential outsiders, but there was little they could do to curb their influence. These informal links in turn drew the Tsar into an ever more aggressive vision of Russian policy in the region. ‘I do not want to seize Korea,’ Nicholas told Prince Henry of Prussia in 1901, ‘but under no circumstances can I allow Japan to become firmly established there. That would be a casus belli.’14

Nicholas further tightened his control over policy by appointing a Viceroy of the Far East with full responsibility not only for civil and military matters but also for relations with Tokyo. The holder of this office, Admiral E. I. Alekseev, was subject directly to the Tsar and thus immune from ministerial supervision. The appointment had been engineered by the clique around Bezobrazov, who saw it as a means of bypassing the relatively cautious Far Eastern policy of the foreign ministry. As a consequence, Russia operated what were in effect two parallel official and non-official imperial policies, enabling Nicholas II to pick between options and play the factions off against each other.15 Admiral Alekseev had no experience or understanding of diplomatic forms and exhibited an abrasive and intransigent style that was bound to alienate and anger his Japanese interlocutors. Whether Nicholas II ever consciously adopted a policy of war with Japan is doubtful, but he certainly carried the lion’s share of responsibility for the war that broke out in 1904, and thus also for the disasters that followed.16

On the eve of the Russo-Japanese War, then, one could say that the Tsar’s influence was up, while that of his ministers was down. But this state of affairs was shortlived, because the catastrophic outcome of the Tsar’s policy sharply diminished his ability to set the agenda. As the news of successive defeats sank in and social unrest engulfed Russia, a group of ministers led by Sergei Witte pushed through reforms designed to unify government. Power was concentrated in a Council of Ministers, headed for the first time by a ‘chairman’ or prime minister. Under Witte and his successor, P. A. Stolypin (1906–11), the executive was shielded to some extent against arbitrary interventions by the monarch. Stolypin in particular, a man of immense determination, intelligence, charisma and tireless industry, managed to assert his personal authority over most of the ministers, achieving a level of coherence in government that had been unknown before 1905. During the Stolypin years, Nicholas seemed ‘curiously absent from political activity’.17

The Tsar did not acquiesce for long in this arrangement. Even while Stolypin was in power, Nicholas found ways of circumventing his control by making deals with individual ministers behind the premier’s back. Among them was Foreign Minister Izvolsky, whose mishandling of negotiations with his Austria-Hungarian counterpart triggered the Bosnian annexation crisis of 1908–9. In return for Vienna’s diplomatic support over Russian access to the Turkish Straits, Izvolsky approved the Austrian annexation of Bosnia-Herzegovina. Neither Prime Minister Stolypin nor his ministerial colleagues had been informed in advance of this daring enterprise, which was cleared directly with Tsar Nicholas himself. By the time of Stolypin’s assassination by terrorists in the autumn of 1911, Nicholas was systematically undercutting his authority by supporting his political opponents. Confronted with a ministerial bloc that threatened to confine his freedom of action, Nicholas withdrew his support and intrigued against the men he had himself placed in power. Witte fell victim to this autocratic behaviour in 1906; Stolypin would have done so if he had not been killed, and his successor, the mild-mannered Vladimir Kokovtsov, was removed from office in February 1914 because he too had revealed himself a devotee of the idea of ‘united government’. I return below to the implications of these machinations for the course of Russian foreign policy – for the moment, the key point is that the years 1911–14 saw a decline in united government and the reassertion of autocratic power.18

Yet this autocratic power was not deployed in support of a consistent policy vision. It was used in a negative way, to safeguard the autonomy and power of the monarch by breaking any political formations that looked as if they might secure the initiative. The consequence of autocratic intervention was thus not the imposition of the Tsar’s will as such, but rather a lasting uncertainty about who had the power to do what – a state of affairs that nourished factional strife and critically undermined the consistency of Russian decision-making.

Of the three imperial cousins, Wilhelm II was and remains the most controversial. The extent of his power within the German executive is still hotly disputed.19 The Kaiser certainly came to the throne intending to be the author of his country’s foreign policy. ‘The Foreign Office? Why, I am the Foreign Office!’ he once exclaimed.20 ‘I am the sole master of German policy,’ he remarked in a letter to the Prince of Wales (the future Edward VII), ‘and my country must follow me wherever I go.’21 Wilhelm took a personal interest in the appointment of ambassadors and occasionally backed personal favourites against the advice of the chancellor and the Foreign Office. To a greater extent than either of his two imperial cousins, he regarded the meetings and correspondence with fellow dynasts that were part of the regular traffic between monarchies as a unique diplomatic resource to be exploited in his country’s interest.22 Like Nicholas II, Wilhelm frequently – especially in the early years of his reign – bypassed his responsible ministers by consulting with ‘favourites’, encouraged factional strife in order to undermine the unity of government, and expounded views that had not been cleared with the relevant ministers or were at odds with the prevailing policy.

It was in this last area – the unauthorized exposition of unsanctioned political views – that the Kaiser achieved the most hostile notice, both from contemporaries and from historians.23 There can be no doubt about the bizarre tone and content of many of the Kaiser’s personal communications in telegrams, letters, marginal comments, conversations, interviews and speeches on foreign and domestic political themes. Their exceptional volume alone is remarkable: the Kaiser spoke, wrote, telegraphed, scribbled and ranted more or less continuously during the thirty years of his reign, and a huge portion of these articulations was recorded and preserved for posterity. Some of them were tasteless or inappropriate. Two examples, both of them linked with the United States, will serve to illustrate the point. On 4 April 1906, Kaiser Wilhelm II was a dinner guest at the US embassy in Berlin. During a lively conversation with his American hosts, the Kaiser spoke of the necessity of securing more space for the rapidly growing German population, which had counted around 40 million at the time of his accession, he told the ambassador, but was now around 60 million. This was a good thing in itself, but the question of nutrition was going to become acute in the next twenty years. On the other hand, large portions of France appeared to be under-populated and in need of development; perhaps one should ask the French government whether they would mind pulling their border back westwards to accommodate the surfeit of Germans? These inane burblings (which we can presume were offered in jest) were earnestly recorded by one of his interlocutors and forwarded to Washington with the next diplomatic bag.24 The other example stems from November 1908, when there was widespread press speculation over a possible war between the United States and Japan. Agitated by this prospect and keen to ingratiate himself with the Atlantic power, the Kaiser fired off a letter to President Roosevelt offering him – this time in all seriousness – a Prussian army corps to be stationed on the Californian coast.25

How exactly did such utterances connect with the world of actual policy outcomes? Any foreign minister or ambassador in a modern democracy who indulged in such grossly inappropriate communications would be sacked on the spot. But how much did such sovereign gaffes matter in the larger scheme of things? The extreme inconsistency of the Kaiser’s utterances makes an assessment of their impact difficult. Had Wilhelm pursued a clear and consistent policy vision, we could simply measure intentions against outcomes, but his intentions were always equivocal and the focus of his attention was always shifting. In the late 1890s, the Kaiser became enthusiastic about a project to create a ‘New Germany’ (Neudeutschland) in Brazil and ‘demanded impatiently’ that migration to that region be encouraged and increased as quickly as possible – needless to say, absolutely nothing came of this. In 1899, he informed Cecil Rhodes that it was his intention to secure ‘Mesopotamia’ as a German colony. In 1900, at the time of the Boxer Rebellion, we find him proposing that the Germans should send an entire army corps to China with a view to partitioning the country. In 1903, he was once again declaring ‘Latin America is our target!’ and urging the Admiralty staff – who apparently had nothing better to do – to prepare invasion plans for Cuba, Puerto Rico and New York, invasion plans that were a complete waste of time, since (among other things) the General Staff never agreed to provide the necessary troops.26

The Kaiser picked up ideas, enthused over them, grew bored or discouraged, and dropped them again. He was angry with the Russian Tsar one week, but infatuated with him the next.27 There were endless alliance projects: for an alliance with Russia and France against Japan and Britain; with Russia, Britain and France against the USA; with China and America against Japan and the Triple Entente, or with Japan and the USA against the Entente, and so on.28 In the autumn of 1896, at a time when relations between Britain and Germany had cooled following tensions over the status of the Transvaal, the Kaiser proposed a continental league with France and Russia for the joint defence of colonial possessions against Britain. At virtually the same time, however, he played with the notion of eliminating any cause of conflict with Britain by simply doing away with all the German colonies except East Africa. But by the spring of 1897, Wilhelm had dropped this idea and was proposing that Germany should enter into a closer relationship with France.29

Wilhelm wasn’t content to fire off notes and marginalia to his ministers, he also broached his ideas directly to the representatives of foreign powers. Sometimes his interventions opposed the direction of official policy, sometimes they endorsed it; sometimes they overshot the mark to arrive at a grossly overdrawn parody of the official view. In 1890, when the Foreign Office was cooling relations with the French, Wilhelm was warming them up again; he did the same thing during the Moroccan crisis of 1905 – while the Foreign Office stepped up the pressure on Paris, Wilhelm assured various foreign generals and journalists and a former French minister that he sought reconciliation with France and had no intention of risking war over Morocco. In March, on the eve of his departure for Tangier, the Kaiser delivered a speech in Bremen in which he announced that the lessons of history had taught him ‘never to strive after an empty power over the world’. The German Empire he added, would have to earn ‘the most absolute trust as a calm, honest and peaceful neighbour’. A number of senior political figures – especially among the hawks within the military command – believed that this speech spiked the guns of official policy on Morocco.30

In January 1904, the Kaiser found himself seated next to King Leopold of the Belgians (who had come to Berlin to celebrate Wilhelm’s birthday) at a gala dinner and used the occasion to inform Leopold that he expected Belgium to side with Germany in the event of a war with France. Should the Belgian king opt to stand with Germany, Wilhelm promised, the Belgians would gain new territories in northern France, and Wilhelm would reward the Belgian king with ‘the crown of old Burgundy’. When Leopold, taken aback, replied that his ministers and the Belgian parliament would hardly accept such a fanciful and audacious plan, Wilhelm retorted that he could not respect a monarch who felt himself to be responsible to ministers and deputies, rather than to the Lord God. If the Belgian king were not more forthcoming, the Kaiser would be obliged to proceed ‘on purely strategic principles’ – in other words, to invade and occupy Belgium. Leopold is said to have been so upset by these remarks that, when rising from his seat at the end of the meal, he put his helmet on the wrong way round.31

It was precisely because of episodes like this that Wilhelm’s ministers sought to keep him at one remove from the actual decision-making process. It is an extraordinary fact that the most important foreign policy decision of Wilhelm’s reign – not to renew the Reinsurance Treaty with Russia in 1890 – was made without the Kaiser’s involvement or prior knowledge.32 In the summer of 1905, Chancellor Bernhard von Bülow entrusted Wilhelm with the task of putting an alliance proposal to Nicholas II off the Finnish coast at Björkö, only to find on the Kaiser’s return that Wilhelm had dared to make an alteration in the draft of the treaty. The chancellor’s response was to tender his resignation. Terrified at the prospect of being abandoned by his most powerful official, Wilhelm immediately backed down; Bülow agreed to remain in office and the treaty amendment was withdrawn.33

The Kaiser constantly complained of being kept out of the loop, of being denied access to important diplomatic documents. He was particularly upset when foreign policy officials insisted on vetting his personal correspondence with foreign heads of state. There was quite a fuss, for example, when the German ambassador in Washington, Speck von Sternburg, refused to pass on a letter from Wilhelm to President Roosevelt in 1908, in which the Kaiser expressed his profound admiration for the American president. It was not the political content of the letter that worried the diplomats, but rather the effusiveness and immaturity of its tone. It was surely unacceptable, one official remarked, that the sovereign of the German Empire should write to the president of the United States ‘as an infatuated schoolboy might write to a pretty seamstress’.34

These were disturbing utterances, to be sure. In an environment where governments were constantly puzzling over each other’s intentions, they were even potentially dangerous. Nevertheless, we should bear three points in mind. The first is that in such encounters, the Kaiser was performing a role of leadership and control that he was incapable of exercising in practice. Secondly, these rhetorical menaces were always associated with imagined scenarios in which Germany was the attacked party. Wilhelm’s indecent proposal to Leopold of the Belgians was not conceived as an offensive venture, but as part of a German response to a French attack. What was bizarre about his reflections on the possible need in a future conflict to breach Belgian neutrality is not the idea of the breach as such – the option of a Belgian invasion was discussed and weighed up by the French and British General Staffs as well – but the context in which it was broached and the identity of the two interlocutors. It was one of this Kaiser’s many peculiarities that he was completely unable to calibrate his behaviour to the contexts in which his high office obliged him to operate. Too often he spoke not like a monarch, but like an over-excited teenager giving free rein to his current preoccupations. He was an extreme exemplar of that Edwardian social category, the club bore who is forever explaining some pet project to the man in the next chair. Small wonder that the prospect of being buttonholed by the Kaiser over lunch or dinner, when escape was impossible, struck fear into the hearts of so many European royals.

Wilhelm’s interventions greatly exercised the men of the German foreign ministry, but they did little to shape the course of German policy. Indeed it may in part have been a deepening sense of impotence and disconnection from the real levers of power that fired up Wilhelm’s recurring fantasies about future world wars between Japan and the USA, invasions of Puerto Rico, global jihad against the British Empire, a German protectorate over China and so on. These were the blue-sky scenarios of an inveterate geopolitical fantasist, not policies as such. And whenever a real conflict seemed imminent, Wilhelm pulled in his horns and quickly found reasons why Germany could not possibly go to war. When tensions with France reached a peak at the end of 1905, Wilhelm took fright and informed Chancellor Bülow that socialist agitation at home absolutely ruled out any offensive action abroad; in the following year, rattled by the news that King Edward VII had just paid an unscheduled visit to the fallen French foreign minister Théophile Delcassé, he warned the chancellor that Germany’s artillery and navy were in no condition to hold out in a conflict.35 Wilhelm could talk tough, but when trouble loomed he tended to turn and run for cover. He would do exactly that during the July Crisis of 1914. ‘It is a curious thing,’ Jules Cambon, French ambassador in Berlin, observed in a letter to a senior official at the French foreign ministry in May 1912, ‘to see how this man, so sudden, so reckless and impulsive in words, is full of caution and patience in action.’36

An overview of the early twentieth-century monarchs suggests a fluctuating and ultimately relatively modest impact on actual policy outcomes. Emperor Franz Joseph of Austria-Hungary read vast quantities of dispatches and met with his foreign ministers regularly. Yet for all his stupendous work as the ‘first bureaucrat’ of his empire, Franz Joseph, like Nicholas II, found it impossible to master the oceans of information that came to his desk. Little effort was made to ensure that he apportioned his time in accordance with the relative importance of the issues arising.37 Austro-Hungarian foreign policy was shaped not by the executive fiats of the Emperor, but by the interaction of factions and lobbies within and around the ministry. Italy’s Victor Emanuel III (r. 1900–1946) worked much less hard than Franz Joseph – he spent most of his time in Piedmont or on his estates at Castelporziano and, though he did make an effort to get through some diplomatic dispatches, he also spent around three hours a day reading newspapers and meticulously listing the errors he found in them. The Italian king cultivated close relations with his foreign ministers and he certainly supported the momentous decision to seize Libya in 1911, but direct interventions were few and far between.38 Nicholas II could favour this or that faction or minister and thereby undermine the cohesion of government, but was unable to set the agenda, especially after the fiasco of the Russo-Japanese War. Wilhelm II was more energetic than Nicholas, but his ministers were also better able than their Russian colleagues to shield the policy-making process against interventions from above. Wilhelm’s initiatives were in any case too disparate and ill coordinated to provide any kind of alternative operational platform.

Whether or not they intervened aggressively in the political process, the continental monarchs nonetheless remained, by virtue of their very existence, an unsettling factor in international relations. The presence in only partially democratized systems of sovereigns who were the putative focal points of their respective executives with access to all state papers and personnel and with ultimate responsibility for every executive decision created ambiguity. A purely dynastic foreign policy, in which monarchs met each other to resolve great affairs of state, was obviously no longer apposite – the futile meeting at Björkö proved that. Yet the temptation to view the monarch as the helmsman and personification of the executive remained strong among diplomats, statesmen and especially the monarchs themselves. Their presence created a persistent uncertainty about where exactly the pivot of the decision-making process rested. In this sense, kings and emperors could become a source of obfuscation in international relations. The resulting lack of clarity dogged efforts to establish secure and transparent relations between states.

Monarchical structures also shrouded the power relations within each executive. In Italy, for example, it was unclear who actually commanded the army – the king, the minister of war or the chief of the General Staff. The Italian staff chief did his best to keep civilians out of his discussions with his German and Austrian counterparts, and civilian officials reciprocated by shutting the officers out of the political loop – with the result, for example, that the chief of Italy’s General Staff was not even informed of the stipulations of the Triple Alliance defining the conditions under which Italy might be called upon to fight a war on behalf of its allies.39

In a situation like this – and we can find analogous conditions in all the continental monarchies – the king or emperor was the sole point at which separate chains of command converged. If he failed to perform an integrating function, if the crown failed to compensate for the insufficiencies, as it were, of the constitution, the system remained unresolved, potentially incoherent. And the continental monarchs often did fail in this role, or rather they refused to perform it in the first place, because they hoped by dealing separately with key functionaries within the executive to preserve what remained of their own initiative and pre-eminence within the system. And this in turn had a malign effect on decision-making processes. In an environment where the decision reached by a responsible minister could be overridden or undermined by a colleague or rival, ministers often found it hard to determine ‘how their activities fitted into the larger picture’.40 The resulting ambient confusion encouraged ministers, officials, military commanders and policy experts to think of themselves as entitled to press their cases in debate, but not as personally responsible for policy outcomes. At the same time, the pressure to secure the favour of the monarch stimulated an atmosphere of competition and sycophancy that militated against the kinds of interdepartmental consultation that might have produced a more balanced approach to decision-making. The consequence was a culture of factionalism and rhetorical excess that would bear dangerous fruit in July 1914.

If the monarchs didn’t determine the course of foreign policy, who did? The obvious answer must surely be: the foreign ministers. These men oversaw the activities of the diplomatic corps and the foreign ministries, read and replied to the most important foreign dispatches and were responsible for explaining and justifying policy to parliament and the public. In reality, however, the power of the foreign ministers to shape policy fluctuated at least as much and varied at least as widely across the European powers as did the political traction of the sovereigns. Their influence depended upon a range of factors: the power and favour of other ministers, especially prime ministers, the attitude and behaviour of the monarch, the willingness of senior foreign ministerial functionaries and ambassadors to follow the minister’s lead and the level of factional instability within the system.

In Russia, the foreign minister and his family occupied private apartments in the ministry, a vast, dark red edifice on the great square facing the Winter Palace, so that his social life and those of his wife and children, were interwoven with the work of the ministry.41 His capacity to shape policy was determined by the dynamics of a political system whose parameters were redefined in the aftermath of the Russo-Japanese War and the 1905 Revolution. A group of powerful ministers moved to establish a more concentrated decision-making structure that would enable the executive to balance domestic and foreign imperatives and to impose discipline on the most senior officials. How exactly this should be achieved was a matter of controversy. The most energetic and talented of the reformers was Sergei Witte, an expert on finance and economic policy who had resigned from the government in 1903 because he opposed its forward policy in Korea. Witte wanted a ‘cabinet’ headed by a ‘prime minister’ with the power not only to discipline his fellow ministers, but also to control their access to the Tsar. The more conservative sometime finance minister Vladimir Kokovtsov* viewed these proposals as an assault on the principle of tsarist autocracy, which he took to be the only form of government suitable to Russian conditions. A compromise was struck: a cabinet of sorts was created in the form of the Council of Ministers, and its chairman or prime minister was granted the power to dismiss an uncooperative minister. But the ‘right of individual report’ – in other words, the right of ministers to present their views to the Tsar independently of the chairman of the council – was retained.

What resulted was a somewhat unresolved arrangement in which everything depended on the balance of initiative between the successive chairmen, their ministers and the Tsar. If the chairman was forceful and strong, he might hope to impose his will on the ministers. But if a confident minister managed to secure the support of the Tsar, he might be able to break with his colleagues and go his own way. With the appointment of Pyotr Stolypin as Chairman of the Council of Ministers in the summer of 1906, the new system acquired a charismatic and dominant leader. And the new foreign minister, Alexander Izvolsky, looked like the kind of politician who would be able to make the new arrangement work. He saw himself as a man of the ‘new politics’ and promptly established foreign ministry liaison posts to manage relations with the Duma. The tone of his dealings with the Tsar was respectful, but less deferential than that of his predecessors. He was committed to the reform and modernization of the ministry and he was an outspoken enthusiast for ‘unified government’.42 Most importantly of all, he agreed with most of his colleagues in the Council of Ministers on the desirability of the settlement with Britain.

It soon emerged, however, that Izvolsky’s vision of Russian foreign policy diverged from that of his colleagues in key ways. Stolypin and Kokovtsov saw the Anglo-Russian Convention as securing the opportunity to withdraw from the adventurism of the years before the Russo-Japanese War and concentrate on the tasks of domestic consolidation and economic growth. For Izvolsky, however, the agreement with England was a licence to pursue a more assertive policy. Izvolsky believed that the cordial relations inaugurated by the Convention would allow him to secure London’s acceptance of free access by Russian warships to the Turkish Straits. This was not just wishful thinking: the British foreign secretary Sir Edward Grey had explicitly encouraged Izvolsky to think along these lines. In a conversation with the Russian ambassador in London in March 1907, Grey had declared that ‘if permanent good relations were to be established’ between the two countries, ‘England would no longer make it a settled object of its policy to maintain the existing arrangement’ in the Straits.43

It was against this background that Izvolsky launched in 1908 his ill-fated negotiations with Aehrenthal, in which he promised Russian approval for the annexation of Bosnia-Herzegovina in return for Austrian support for a revision of the Straits settlement. The agreement with Aehrenthal was supposed to be the first step towards a comprehensive revision. This démarche was undertaken with the support of the Tsar; indeed it may have been Nicholas II who pushed Izvolsky into offering the Austrians a deal. Having been an ardent exponent of Far Eastern expansion before 1904, the Tsar was now focusing his attention on the Straits: ‘the thought of taking the Dardanelles and Constantinople’, one Russian politician recalled, ‘was constantly on his mind’.44 Rather than risking rejection from Stolypin, Kokovtsov and the other ministers, Izvolsky exploited the right of individual report. It was the highpoint of the foreign minister’s political independence – an independence acquired by playing the margins between the different power centres in the system. But the triumph was shortlived. Since there was no deal to be had in London, the Straits policy failed. Izvolsky was disgraced in the eyes of Russian public opinion and returned to face the ire of Stolypin and Kokovtsov.

In the short term, then, the débâcle of the Bosnian annexation crisis (like the débâcle of the Japanese war) led to a reassertion of the collective authority of the Council of Ministers. The Tsar lost the initiative, at least for the moment. Izvolsky was forced to back down and to submit to the discipline of ‘united government’. Stolypin, on the other hand, now reached the peak of his power. Conservative supporters of the autocracy began to view him with alarm as an over-mighty ‘lord’ or ‘Grand Vizier’ who had usurped the powers of his imperial master. The choice of Sergei Sazonov to replace Izvolsky in September 1910 appeared to reinforce Stolypin’s dominance. Sazonov was a relatively junior diplomat, had little experience in senior chancellery posts within the ministry of foreign affairs and lacked aristocratic and imperial connections. He had little knowledge of St Petersburg politics and scarcely any influence in government circles. His chief qualifications for office, critical outsiders noted, were a reputation for ‘mediocrity and obedience’ and the fact that he was Stolypin’s brother-in law.45

After the débâcle of Izvolsky’s policy and his departure from office, Russian foreign policy thus bore the imprint not of the foreign minister, but of the prime minister, Chairman Pyotr Stolypin, whose view was that Russia needed peace at all costs and should pursue a policy of conciliation on every front. The consequence was a period of pronounced rapprochement with Berlin, despite the recent tensions over Bosnia. In November 1910, a visit by Nicholas II and Sazonov to Potsdam set in train discussions culminating in an agreement marking a highpoint in Russo-German détente.46

Stolypin’s assassination at first did little to change the orientation of policy. In the immediate aftermath of his patron’s death, Sazonov struggled to find his own voice. But Sazonov’s weakness, in combination with Stolypin’s death, in turn amplified a further potential instability within the system; the most experienced and confident Russian agents abroad were free to play a more independent role. Two ministers in particular, N. V. Charykov in Constantinople and Nikolai Hartwig in Belgrade, sensing a loosening of control from St Petersburg, embarked on potentially hazardous independent initiatives in order to capitalize on the worsening political situation in the Balkans.47 In the meanwhile, the Russian ambassador to France was none other than the former foreign minister, Alexander Izvolsky, whose determination to shape policy – on the Balkans especially – remained undiminished after his transfer back into the diplomatic service. Izvolsky hatched his own intrigues in Paris, all the while ‘hectoring Sazonov through the diplomatic pouch’.48

Sazonov’s eclipse was not permanent. With time, he began to make his own way in Balkan policy, exploiting the political weakness of Kokovtsov, Stolypin’s successor as Chairman of the Council of Ministers. The key point is that the influences shaping policy in Russia were constantly changing. Power flowed through the system, concentrating at different points: the monarch, the foreign minister, the prime minister, the ambassadors. Indeed we can speak of a kind of ‘hydraulics of power’, in which the waxing of one node in the system produced the waning of others. And the adversarial dynamic within the system was further energized by the tension between opposed policy options. Russian liberal nationalists and pan-Slavs were likely to favour a forward policy on the Turkish Straits and a posture of solidarity with the Slavic ‘little brothers’ on the Balkan peninsula. Conservatives, by contrast, tended to be acutely aware of Russia’s inner political and financial weakness and the dangers – as Kokovtsov put it – of pursuing ‘an active foreign policy at the expense of the peasant’s stomach’; they therefore favoured a policy of peace at all costs.49

When the significance of the Bosnian annexation crisis was debated in the Duma in the spring of 1909, for example, the conservative interests represented in the Council of the United Nobility argued that the annexation had in no way damaged Russian interests or security and that Russia should adopt a policy of complete non-interference in Balkan affairs, while seeking reconciliation with Berlin. The real enemy, they argued, was Britain, which was trying to push Russia into a war with Germany in order to consolidate British control of world markets. Against this position, the pro-French and pro-British liberals of the Constitutional Democrat (Cadet) Party called for the transformation of the Triple Entente into a Triple Alliance that would enable Russia to project power in the Balkan region and arrest the decline of its great power status.50 This was one of the central problems confronting all the foreign policy executives (and those who try to understand them today): the ‘national interest’ was not an objective imperative pressing in upon government from the world outside, but the projection of particular interests within the political elite itself.51

In France, there was a different but broadly analogous dynamic. To a much greater extent than in Russia, the foreign ministry, or the Quai d’Orsay as it was known on account of its location, enjoyed formidable power and autonomy. It was a socially cohesive and relatively stable organization with a high sense of its own calling. A dense network of family connections reinforced the ministry’s esprit de corps: the brothers Jules and Paul Cambon were the ambassadors to Berlin and London respectively, the ambassador to St Petersburg in 1914, Maurice Paléologue, was Jules and Paul’s brother-in-law, and there were other dynasties – the Herbettes, the de Margeries, and the de Courcels, to name just a few. The ministry of foreign affairs protected its independence through habits of secrecy. Sensitive information was only rarely released to cabinet ministers. It was not unusual for senior functionaries to withhold information from the most senior politicians, even from the president of the Republic himself. In January 1895, for example, during the tenure of Foreign Minister Gabriel Hanotaux, President Casimir Périer resigned after only six months in office, protesting that the ministry of foreign affairs had failed to keep him informed even of the most important developments. Policy documents were treated as arcana. Raymond Poincaré was informed of the details of the Franco-Russian Alliance only when he became premier and foreign minister in 1912.52

But the relative independence of the ministry did not necessarily confer power and autonomy upon the minister. French foreign ministers tended to be weak, weaker indeed than their own ministerial staff. One reason for this was the relatively rapid turnover of ministers, a consequence of the perennially high levels of political turbulence in pre-war France. Between 1 January 1913 and the outbreak of war, for example, there were no fewer than six different foreign ministers. Ministerial office was a more transitory and less important stage in the life cycle of French politicians than in Britain, Germany or Austria-Hungary. And in the absence of any code of cabinet solidarity, the energies and ambition of ministers tended to be consumed in the bitter factional strife that was part of the everyday life of government in the Third Republic.

Of course, there were exceptions to this rule. If a minister stayed in power for long enough and possessed sufficient determination and industry, he could certainly imprint his personality upon the workings of the ministry. Théophile Delcassé is a good example. He remained in office for a staggering seven years (from June 1898 until June 1905) and established his mastery over the ministry not only through tireless work, but also by ignoring his permanent officials in Paris and cultivating a network of like-minded ambassadors and functionaries from across the organization. In France, as elsewhere in Europe, the waxing and waning of specific offices within the system produced adjustments in the distribution of power. Under a forceful minister like Delcassé, the power-share of the senior civil service functionaries known collectively as the Centrale tended to shrink, while the ambassadors, freed from the constraints imposed by the centre, flourished, just as Izvolsky and Hartwig did during the early years of Sazonov. Delcassé’s long spell in office saw the emergence of an inner cabinet of senior ambassadors around the Cambon brothers (London and Berlin) and Camille Barrère (Rome). The ambassadors met regularly in Paris to discuss policy and lobby key officials. They communicated with the minister through private letters, bypassing the functionaries of the Centrale.

The senior ambassadors developed an extraordinarily elevated sense of their own importance, especially if we measure it against the professional ethos of today’s ambassadors. Paul Cambon is a characteristic example: he remarked in a letter of 1901 that the whole of French diplomatic history amounted to little more than a long list of attempts by agents abroad to achieve something in the face of resistance from Paris. When he disagreed with his official instructions from the capital, he not infrequently burned them. During a tense conversation with Justin de Selves, minister of foreign affairs from June 1911 until January 1912, Cambon somewhat tactlessly informed de Selves that he considered himself the minister’s equal.53 This claim looks less bizarre if we bear in mind that between 1898, when he became ambassador to London, and the summer of 1914, Cambon saw nine ministers enter and leave office – two of them did so twice. Cambon did not regard himself as a subordinate employee of the government, but as a servant of France whose expertise entitled him to a major role in the policy-making process.

Underpinning Cambon’s exalted sense of self was the belief – shared by many of the senior ambassadors – that one did not merely represent France, one personified it. Though he was ambassador in London from 1898 until 1920, Cambon spoke not a word of English. During his meetings with Edward Grey (who spoke no French), he insisted that every utterance be translated into French, including easily recognized words such as ‘yes’.54 He firmly believed – like many members of the French elite – that French was the only language capable of articulating rational thought and he objected to the foundation of French schools in Britain on the eccentric grounds that French people raised in Britain tended to end up mentally retarded.55 Cambon and Delcassé established a close working relationship whose fruit was the Entente Cordiale of 1904. It was Cambon, more than anyone else, who laid the groundwork for the Entente, working hard from 1901 to persuade his British interlocutors to settle over Morocco, while at the same time urging Delcassé to relinquish France’s putative claims on Egypt.56

Things changed after Delcassé’s departure at the height of the first Moroccan crisis. His successors were less forceful and authoritative figures. Maurice Rouvier and Léon Bourgeois occupied the minister’s post for only ten and seven months respectively; Stéphen Pichon had a longer spell, from October 1906 to March 1911, but he abhorred regular hard work and was often absent from his desk in the Quai d’Orsay. The result was a steady rise in the influence of the Centrale.57 By 1911, two factional groupings had coalesced within the world of French foreign affairs. On the one side were the old ambassadors and their allies within the administration, who tended to favour détente with Germany and a pragmatic, open-ended approach to France’s foreign relations. On the other were the ‘Young Turks’, as Jules Cambon called them, of the Centrale.

The ambassadors wielded the authority of age and the experience acquired over long years in the field. The men of the Centrale, on the other hand, possessed formidable institutional and structural advantages. They could issue press releases, they controlled the transmission of official documents, and above all, they had access to the cabinet noir within the ministerial office – a small but important department responsible for opening letters and intercepting and deciphering diplomatic traffic. And just as in Russia, these structural and adversarial divisions coincided with divergent views of external relations. The agitations of the internal struggle for influence could thus have a direct impact on the orientation of policy.

French policy on the Morocco question is a case in point. After the Franco-German clash over Morocco in 1905 and the German débâcle at Algeciras in the following year, Paris and Berlin struggled to find an accord that would put the Moroccan conflict behind them. On the French side, opinions were divided on how German claims vis-à-vis Morocco ought to be handled. Should Paris seek to accommodate German interests in Morocco, or should it proceed as if German rights in the territory simply did not exist? The most outspoken exponent of the first view was Jules Cambon, brother of Paul and French ambassador to Berlin. Cambon had several reasons for seeking détente with Germany. The Germans, he argued, had a right to speak up for the interests of their industrialists and investors abroad. He also formed the view that the most senior German policy-makers – from the Kaiser and his close friend Count Philipp zu Eulenburg, to the chancellor Bernhard von Bülow, the German foreign secretary Heinrich von Tschirschky and his successor Wilhelm von Schoen – were sincerely desirous of better relations with Paris. It was France, he argued, with its factionalized politics and its perfervid nationalist press, that was chiefly responsible for the misunderstandings that had arisen between the two neighbouring powers. The fruit of Cambon’s efforts was the Franco-German Accord of 9 February 1909, which excluded Berlin from any political initiative in Morocco, while affirming the value of Franco-German cooperation in the economic sphere.58

On the other side of the argument were the men of the Centrale who opposed concessions of any kind. From behind the scenes, key officials such as the maniacally Germanophobe Maurice Herbette, head of communications at the Quai d’Orsay from 1907 to 1911, used his extensive newspaper contacts to sabotage negotiations by leaking potentially controversial conciliatory proposals to the French press before they had been seen by the Germans, and even by stirring up jingoist press campaigns against Cambon himself.59 Herbette was an excellent example of an official who managed to imprint his own outlook on French policy-making. In a memorandum of 1908 that resembles Eyre Crowe’s famous British Foreign Office memorandum of the previous year (except for the fact that whereas Crowe’s document fills twenty-five pages of print, Herbette’s stretches to an astonishing 300 pages of chaotic manuscript), Herbette painted the recent history of Franco-German relations in the darkest colours as a catalogue of malign ruses, ‘insinuations’ and menaces. The Germans, he wrote, were insincere, suspicious, disloyal, duplicitous. Their efforts to conciliate were cunning ploys designed to trick and isolate France; their representations on behalf of their interests abroad were mere provocations; their foreign policy a repellent alternaton of ‘menaces and promises’. France, he concluded, bore absolutely none of the responsibility for the poor state of relations between the two states, her handling of Germany had always been unimpeachably ‘conciliatory and dignified’: ‘an impartial examination of the documents proves that France and its governments cannot in any way be made responsible for this situation’. Like Crowe’s memorandum of the previous year, Herbette’s memorandum was focused on the ascription of reprehensible motives and ‘symptoms’ rather than on naming actual transgressions.60 There is no evidence that Herbette ever changed his views on Germany. He and other intransigent officials within the Centrale were a formidable obstacle to détente with Berlin.

With the collapse of the government at the beginning of March 1911 and Pichon’s fall from office, the influence of the Centrale reached an all-time high. Pichon’s successor as foreign minister was the conscientious but completely inexperienced Jean Cruppi, a former magistrate whose main qualification for the foreign affairs portfolio was that so many individuals better suited for the post had already turned it down – an indication of the low regard in which ministerial posts were held. During Cruppi’s short period at the ministry – he took office on 2 March 1911 and was out by 27 June – the Centrale seized effective control over policy. Under pressure from the political and commercial director at the Quai d’Orsay, Cruppi agreed to terminate all economic links with Germany in Morocco, an unequivocal repudiation of the 1909 accord. A sequence of unilateral initiatives followed – negotiations for the joint Franco-German management of a railway from Fez to Tangier were broken off without notice and a new financial agreement with Morocco was drafted in which there was no mention whatsoever of German participation. Cambon was horrified: the French, he warned, were conducting their relations with Germany in an ‘esprit de chicane’.61

Finally, in deciding, without consulting other interested countries, to deploy a substantial force of French metropolitan troops to the Moroccan city of Fez in the spring of 1911 on the pretext of repressing a local uprising and protecting French colonists, Paris broke comprehensively both with the Act of Algeciras and with the Franco-German Accord of 1909. The claim that this deployment was needed to protect the European community in Fez was bogus; the rebellion had occurred deep in the Moroccan interior and the danger to Europeans was remote. The Sultan’s appeal for assistance from Paris had in fact been formulated by the French consul and was passed to him for signature after Paris had already decided to intervene.62 We return below to the Agadir crisis that followed these steps – for the moment the crucial point is that it was not the French government as such that generated the forward policy in Morocco, but the hawks of the Quai d’Orsay, whose influence over policy was unrivalled in the spring and early summer of 1911.63 Here, as in Russia, the flux of power from one part of the executive to another produced rapid shifts in the tone and direction of policy.

In Germany, too, foreign policy was shaped by the interaction between power-centres within the system. But there were some structural differences. The most important was that, within the complex federal structure created to house the German Empire founded in 1871, the role of foreign minister was largely absorbed in the office of the imperial chancellor. This pivotal post was in fact a composite, in which a range of different offices were linked in personal union. The chancellor of the German Empire was usually also both the minister-president and the foreign minister of Prussia, the dominant federal state, whose territory encompassed about three-fifths of the citizens and territory of the new empire. There was no imperial foreign minister, just an imperial state secretary for foreign affairs, who was the direct subordinate of the chancellor. And the chancellor’s intimate link with the making of foreign policy was physically manifested in the fact that his private apartments were accommodated in the small and crowded palace at Wilhelmstrasse 76, where the German Foreign Office was also at home.

This was the system that had allowed Otto von Bismarck to dominate the unique constitutional structure he had helped to create in the aftermath of the German Wars of Unification and single-handedly to manage its external affairs. Bismarck’s departure in the early spring of 1890 left a power vacuum that no one could fill.64 Leo von Caprivi, the first post-Bismarckian chancellor and Prussian foreign minister, had no experience in foreign affairs. Caprivi’s epoch-making decision not to renew the Reinsurance Treaty was in fact driven by a faction within the German Foreign Office which had secretly opposed the Bismarckian line for some time. Led by Friedrich von Holstein, director of the political department at the Foreign Office, a highly intelligent, hyper-articulate, privately malicious and socially reclusive individual who aroused admiration but not much affection in his fellows, this faction had little difficulty in winning over the new chancellor. Just as in France, in other words, the weakness of the foreign minister (or in this case, chancellor) meant that the initiative slipped towards the permanent officials of the Wilhelmstrasse, the Berlin equivalent of the Centrale. This state of affairs continued under Caprivi’s successor, Prince Chlodwig von Hohenlohe-Schillingsfürst, who occupied the chancellorship in the years 1894–9. It was Holstein, not the chancellor or the imperial foreign secretary, who determined the shape of German foreign policy in the early and mid-1890s.

Holstein could do this in part because he had excellent ties both with the responsible politicians and with the coterie of advisers around Kaiser Wilhelm II.65 These were the years when Wilhelm was most energetically throwing his weight about, determined to become ‘his own Bismarck’ and to establish his own ‘personal rule’ over the cumbersome German system. He failed in this objective, but his antics did paradoxically produce a concentration of executive power, by virtue of the fact that the most senior politicians and officials clubbed together to ward off sovereign threats to the integrity of the decision-making process. Friedrich von Holstein, Count Philipp zu Eulenburg, the Kaiser’s intimate friend and influential adviser, and even the ineffectual chancellor Hohenlohe became adept at ‘managing the Kaiser’.66 They did so mainly by not taking him too seriously. In a letter of February 1897 to Eulenburg, Holstein observed that this was the ‘third policy programme’ he had seen from the sovereign in three months. Eulenburg told him to take it easy: the Kaiser’s projects were not ‘programmes’, he assured Holstein, but whimsical ‘marginal jottings’ of limited import for the conduct of policy. The chancellor, too, was unconcerned. ‘It seems that His Majesty is recommending another new programme,’ Hohenlohe wrote, ‘but I don’t take it too tragically; I’ve seen too many programmes come and go.’67

It was Eulenburg and Holstein who placed the career diplomat Bernhard von Bülow on the road to the chancellorship. Already as imperial foreign secretary under Chancellor Hohenlohe (1897–1900), Bülow had been able, with the help of his friends, to secure control of German policy. His position was even stronger after 1900, when the Kaiser, acting on Eulenburg’s advice, appointed Bülow to the chancellorship. More than any chancellor before him, Bülow deployed all the arts of the seasoned courtier to draw Wilhelm into his confidence. Despite internal rivalries and suspicions, the Bülow–Holstein–Eulenburg troika for a time kept a remarkably tight hold on policy-making.68 The system worked well as long as three conditions were satisfied: (i) the partners were in agreement on their ultimate objectives, (ii) their policies were successful, and (iii) the Kaiser remained quiescent.

During the Morocco crisis of 1905–6, all three of these preconditions lapsed. First, Holstein and Bülow found themselves in disagreement on German aims in Morocco (Bülow wanted compensation; Holstein hoped, unrealistically, to explode the Anglo-French Entente). Then it became clear at the conference of Algeciras in 1906, where the German delegation found itself isolated and outmanoeuvred by France, that the Morocco policy had been disastrously mishandled. One consequence of this fiasco was that the Kaiser, who had always been sceptical of the Moroccan démarche, disassociated himself from his chancellor and re-emerged as a threat to the policy-making process.69

It was the inverse of what happened at around the same time in Russia, where the débâcle of the Tsar’s East Asia policy weakened the sovereign’s position and set the scene for the assertion of cabinet responsibility. In Germany, by contrast, the failure of the senior officials temporarily restored the Kaiser’s freedom of movement. In January 1906, when the office of foreign secretary suddenly fell vacant (because its previous incumbent had died of overwork), Wilhelm II imposed a replacement of his own choice, disregarding Bulow’s advice. It was widely understood that Heinrich von Tschirschky, a close associate of the Kaiser who had often accompanied him on his travels, had been appointed to replace the Bülow–Holstein policy with something more conciliatory. By early 1907, there was talk of feuding between the ‘Bülow camp’ and the ‘Tschirschky circle’.

In the final years of his chancellorship, which lasted until 1909, Bülow fought ruthlessly to regain his former supremacy. He tried, as Bismarck had done in the 1880s, to build a new parliamentary bloc defined by loyalty to his own person, in the hope of rendering himself politically indispensable to the Kaiser. He helped to engineer the shattering scandal of the ‘Daily Telegraph Affair’ (November 1908) in which jejune remarks by Wilhelm in an interview published in a British newspaper triggered a wave of protest from a German public tired of the Kaiser’s public indiscretions. Bülow was even indirectly involved in the chain of press campaigns in 1907–8 that exposed homosexuals within the Kaiser’s intimate circle – including Eulenburg, the chancellor’s erstwhile friend and ally, now reviled by Bülow, who was himself probably homosexual, as a potential rival for the Kaiser’s favour.70 Despite these extravagant manoeuvres, Bülow never regained his earlier influence over foreign policy.71 The appointment of Theobald von Bethmann Hollweg to the chancellorship on 14 July 1909 brought a degree of stabilization. Bethmann may have lacked a background in foreign affairs, but he was a steady, moderate and formidable figure who quickly asserted his authority over the ministers and imperial secretaries.72 It helped that after the shock and humiliation of the Daily Telegraph and Eulenburg scandals, the Kaiser was less inclined than in earlier years to challenge the authority of his ministers in public.

Britain presents a rather different picture. Unlike Stolypin and Kokovtsov or their German colleagues Bülow and Bethmann Hollweg, the British foreign secretary, Sir Edward Grey, had no reason to fear unwanted interventions by the sovereign. George V was perfectly happy to be led by his foreign secretary in international matters. And Grey also enjoyed the unstinting support of his prime minister, Herbert Asquith. Nor did he have to contend, as his French colleagues did, with over-mighty functionaries in his own Foreign Office. Grey’s continuity in office alone assured him a more consistent influence over policy than most of his French colleagues ever enjoyed. While Edward Grey remained in control of the Foreign Office for the years between December 1905 and December 1916, the same period in France saw fifteen ministers of foreign affairs come and go. Moreover, Grey’s arrival at the Foreign Office consolidated the influence of a network of senior officials who broadly shared his view of British foreign policy. Grey was without doubt the most powerful foreign minister of pre-war Europe.

Like most of his nineteenth-century predecessors, Sir Edward Grey was born into the top tier of British society. He was the descendant of a distinguished line of Whig grandees – his great grand-uncle was the Earl Grey of the 1832 Reform Bill and eponym of the popular scented tea. Of all the politicians who walked the European political stage before 1914, Grey is one of the most baffling. His aloof and lofty style did not go down well with the rank and file of the Liberal Party. He had long been a Liberal MP, yet he believed that foreign policy was too important to be subjected to the agitations of parliamentary debate. He was a foreign secretary who knew little of the world outside Britain, had never shown much interest in travelling, spoke no foreign languages and felt ill at ease in the company of foreigners. He was a Liberal politician whose vision of policy was opposed by most Liberals and supported by most Conservatives. He became the most powerful member of the faction known as ‘the liberal imperialists’, yet he appears to have cared little for the British Empire – his views on foreign policy and national security were tightly focused on the European continent.

There was a curious dissonance between Grey’s persona – private and public – and his modus operandi in politics. As a young man, he had shown little sign of intellectual curiosity, political ambition or drive. He idled away his years at Balliol College, Oxford, where he spent most of his time becoming Varsity champion in real tennis, before graduating with a third in Jurisprudence, a subject he had chosen because it was reputed to be easy. His first (unpaid) political post was fixed up through Whig family connections. As an adult, Grey always cultivated the image of a man for whom politics was a wearisome duty, rather than a vocation. When parliament was dissolved in 1895 following a Liberal defeat in a key vote, Grey, who was then serving as an MP and parliamentary under-secretary of state for foreign affairs, professed to feel no regrets. ‘I shall never be in office again and the days of my stay in the House of Commons are probably numbered. We [he and his wife Dorothy] are both very relieved.’73 Grey was a passionate naturalist, birdwatcher and fisherman. By the turn of the century, he was already well known as the author of a justly celebrated essay on fly-fishing. Even as foreign secretary, he was apt to leave his desk at the earliest opportunity for country jaunts and disliked being recalled to London any sooner than was absolutely necessary. Some of those who worked with Grey, such as the diplomat Cecil Spring-Rice, felt that the country excursions were getting out of hand and that the foreign secretary would be well advised to ‘spare some time from his ducks to learn French’.74 Colleagues found it difficult to discern political motivation in Grey; he struck them as ‘devoid of personal ambition, aloof and unapproachable’.75

And yet Grey did develop a deep appetite for power and a readiness to deploy conspiratorial methods in order to obtain and hold on to it. His accession to the post of foreign secretary was the fruit of careful planning with his trusted friends and fellow liberal imperialists, Herbert Asquith and R. B. Haldane. In the ‘Relugas Compact’, a plot hatched at Grey’s fishing lodge in the Scottish hamlet of that name, the three men agreed to push aside the Liberal leader Sir Henry Campbell-Bannerman and establish themselves in key cabinet posts. Secretiveness and a preference for discreet, behind-the-scenes dealing remained a hallmark of his style as foreign secretary. The posture of gentlemanly diffidence belied an intuitive feel for the methods and tactics of adversarial politics.

Grey quickly secured unchallenged control over the policy-making process, ensuring that British policy focused primarily on the ‘German threat’. It would be going too far, of course, to view this reorientation of British policy as a function solely of Edward Grey’s power. Grey was not the puppet-master; the men of the new policy – Bertie, Hardinge, Nicolson, Mallet, Tyrrell and so on – were not manipulated or controlled by him, but worked alongside him as the members of a loose coalition driven by shared sentiments. Indeed, Grey was quite dependent on some of these collaborators – many of his decisions and memoranda, for example, were modelled closely on reports from Hardinge.76 The ascendancy of the Grey group was eased by recent structural reforms to the Foreign Office whose object had not been to reinforce the authority of the foreign secretary, but rather to parcel influence out more widely across a range of senior officials.77 Nevertheless, the energy and vigilance with which Grey maintained his ascendancy are impressive. It helped, of course, that he enjoyed the firm support of his former co-conspirator Herbert Asquith, prime minister from 1908 until 1916. The backing of a large part of the Conservative bloc in the House of Commons was another important asset – and Grey proved adept at maintaining his cross-party appeal.

But Grey’s plenitude of power and consistency of vision did not entirely protect British policy-making from the agitations characteristic of the European executives. The anti-German position adopted by the Grey group did not enjoy wide support outside the Foreign Office. It was not even backed by the majority of the British cabinet. The Liberal government, and the Liberal movement more generally, were polarized by the tension between liberal imperialist and radical elements. Many of the leading radicals, and they included some of the most venerable figures in the party, deplored the foreign secretary’s policy of alignment with Russia. They accused Grey and his associates of adopting a pose towards Germany that was unnecessarily provocative. They doubted whether the advantages of appeasing Russia outweighed the potential benefits of friendship with the German Empire. They worried whether the creation of a Triple Entente might not pressure Germany into adopting an ever more aggressive stance and they pressed for détente with Berlin. A further problem was the complexion of British public opinion, especially within the cultural and political elite, which, despite intermittent Anglo-German ‘press wars’, was drifting into a more pro-German mood during the last few years before the outbreak of war.78 Antagonism to Germany coexisted across the British elites with multi-layered cultural ties and a deep admiration of the country’s cultural, economic and scientific achievements.79

Grey met these challenges by shielding the policy-making process from the scrutiny of unfriendly eyes. Documents emanating from his desk were often marked ‘For Limited Circulation Only’; a typical annotation from his private secretary reads ‘Sir E. Grey thinks this circulation sufficient’. Consultations on important policy decisions – notably regarding the deepening commitment to France – were confined to trusted contacts within the administration. Cabinet was not informed, for example, of the discussions between France and Britain in December 1905 and May 1906, in which military representatives of both countries agreed in principle the form that a British military intervention in support of France would take in the event of war. This mode of proceeding suited Grey’s elitist understanding of politics and his avowed view of the Entente, which was that it should be cultivated ‘in a loyal and generous spirit’ ensuring that any pitfalls arising would ‘strengthen’ rather than weaken the ‘Agreement’, and that the gradual advance into a deepening commitment should always be insulated from ‘party controversy’.80 In other words, Grey ran a double-track policy. In public, he repeatedly denied that Britain was under any obligation to come to France’s aid. London’s hands remained absolutely free. Pressed by hostile colleagues, he could always say that the interlinked mobilization scenarios of the military were mere contingency plans. By means of these complex manoeuvres, Grey was able to impart a remarkable inner consistency to the management of British foreign policy.

Yet it is easy to see how this state of affairs – driven by the shifting balance of power between factions within the British government and the political elite – gave rise to confusion. To those French interlocutors who dealt directly with the foreign secretary and his associates, it was clear that ‘Sir Grey’, as some of them quaintly called him, would stand by France in the event of a war, notwithstanding the official insistence on the non-binding character of the Entente. But to the Germans, who were not privy to these conversations, it looked very much as if Britain might stand aside from the continental coalition, especially if the Franco-Russian Alliance took the initiative against Germany, rather than the other way around.