3

The Students

JOANNE

In our green-shingled house, in our neighborhood of identical Colonials and split-levels so new that the saplings in the yards provided no shade, the piano had pride of place in the living room. The instrument’s upholstered bench was never empty, always occupied by one of my older sisters. The rest of the room was strictly off-limits. With its tailored couch and floor-length drapes, the room was immaculate, never a knickknack out of place, and nobody ever sat in there except on holidays. Nonetheless, my mom vacuumed the sofa cushions, moved the overstuffed armchair to clean underneath it, and dusted the sideboards in that room every Wednesday morning.

This is the room where I realized that I had no talent.

Both of my sisters were becoming accomplished musicians. Michele, having graduated from Mr. K’s beginner orchestra, was progressing rapidly on the violin, while Ronni would soon take up the flute. Both took piano lessons. At any hour of the day, somebody was playing an instrument somewhere, and often two different melodies would be coming at you in uncoordinated stereo. The two of them were always singing together, too, harmonizing during car rides in the big maroon Oldsmobile and telling me to shut up if I tried to join in.

My dad, an energetic amateur photographer, was there to capture it all on film. One sister would happily take her place at the piano bench, while the other would pose with her instrument. And I… I had nothing. “Try holding up your arms like you’re a ballerina,” my father would coach me helpfully when he photographed the three of us grouped around the piano, so there would be some display of artistry demonstrated by the apparently ability-free little sister. Except I didn’t take ballet, and my attempts at dance usually ended with me banging into a wall.

“I want to play an instrument, too,” I announced one day, as my dad, having rearranged our photographic tableau around the piano yet again, stepped back and fiddled with the camera viewfinder.

“You’re too young,” my mom yelled back from the kitchen.

I tugged at my jumper, an uncomfortable concoction of stiff embroidered cotton with a matching white blouse and scratchy elastic cuffs that left indentations on my arms.

“Why can’t I take piano lessons?” I ventured again.

“Because I said so.” From the kitchen again.

Of course no is a familiar word to any youngest child. As in, “No new clothes—your sisters’ hand-me-downs are perfectly fine.” And “No long hair like your sisters—your pixie cut will do”—that would be the sheared-sheep look that compelled strangers to pat me on the head and call me a sweet little boy. “No music lessons” was just another indignity to add to the list.

The truth is, I was always a half step behind my chatty, quick-witted sisters. When I was three, my mother had attempted to enroll me in a nursery school run by the home economics class at East Brunswick High School. I cried so hard that the teachers gave up and sent me home, to the great glee of my sisters who would forever taunt me for flunking out of preschool. After that, my teachers kept telling my parents that I was far too timid. I never fought back, they told my parents with concern, even when the girl I considered my best friend nicknamed me “Dodo,” as in the television cartoon Dodo, the Kid from Outer Space.

I didn’t mind the teasing. My parents always figured me for the easygoing one: with two precocious older daughters, they were happy to have the littlest one be good-natured, if not terribly bright. Anyway, even if I had tried to protest, chances are nobody would have noticed.

The piano in our living room had been my dad’s idea. Not that he knew how to play it. He was born in Oakland, California, in 1931 to a Romanian immigrant mother and a father who grew up as an orphan, shuttled from one impoverished relative to another. His parents named him Burton but called him Boots, to rhyme with his older brother Sydney’s nickname, Scoots. When Dad was a toddler, my grandmother was hauled in by the Oakland police because he bore such a strong resemblance to the missing Lindbergh baby, the aviator Charles Lindbergh’s kidnapped son who would soon turn up murdered. My grandmother had to produce her son’s birth certificate before the cops let her go, prompting a local newspaper to print side-by-side photos of the two toddlers above the headline “Lindbergh Baby’s Double Gives His Family Trouble.”

Money was always tight on my grandfather’s wages as a traveling X-ray technician. The family moved frequently, hopscotching across the country to St. Louis and Brooklyn before landing in Queens, New York, where Boots entered his fifth elementary school in five years. He slept in the galley kitchen of the family’s one-bedroom apartment, cramming his lanky frame—he grew to be six feet three inches—into a narrow bed. When he joined the Boy Scouts, he was humiliated by having to wear his much older brother’s outdated Scout knickers years after the uniform switched to long pants. To help make ends meet, he went to work starting at age nine, first selling Liberty magazine subscriptions, then the Saturday Evening Post, then running errands for a butcher and delivering laundry for a dry cleaner during World War II, when there was a steel shortage and he had to wait by the door for customers to return their metal clothes hangers.

My father was what they euphemistically called a “slow starter”—he was held back a year and sat in the back row cracking jokes until an astute teacher figured out the problem was he had such horrendous eyesight that he couldn’t see the blackboard. By the time he hit high school he had become a standout student. At a Boy Scout party one night, he met my mother. She had dark brown hair, flirtatious dark eyes, and long black eyelashes, and she attended the same gifted high school program that he did. She was fourteen years old. He was smitten.

He courted her through high school and while working his way through Columbia University, commuting from home by subway three hours a day to save money and working in the university’s atomic physics laboratory, helping tend to the atom-splitting cyclotron in the basement of Pupin Hall. During the summers, he popped salt pills to keep from getting dehydrated while packing boxes in a Garment District sweatshop, earning enough money to buy a diamond engagement ring. “I married your father because he was the only man I could find who was smarter than me,” my mother would say.

My father’s interest in music grew out of a peculiar hobby: the theremin, a strange electronic instrument that was the forerunner of the synthesizer. He had learned to play the theremin from my grandfather, an inveterate electronic tinkerer who built several of them from scratch, assembling them inside empty wooden radio cabinets out of spare radio parts and glass tubes. The instrument made a satisfyingly eerie whine, and my grandfather had earned a few extra bucks creating sound effects for television sound tracks. He even made a 1962 appearance on the TV game show I’ve Got a Secret, a surprisingly dapper figure who stumped panelists Bill Cullen and Henry Morgan with his mystery contraption before performing his rendition of the Rodgers and Hart classic “Lover.” Such was my father’s sentimental attachment to it that it was the only possession he brought with him to my parents’ marriage. But my father always regretted that he couldn’t read music and was resentful that his parents refused him a proper music education.

Dad was determined to provide for his kids what his own parents had not. So after my mother’s parents threw them a properly extravagant Manhattan wedding in the penthouse of the St. Moritz hotel overlooking Central Park, they moved to the burgeoning suburbs of New Jersey, where he began his management trainee job. He had been working his way up the corporate ladder since then. By the time the third girl in five years was born (they were so sure I would finally be a boy that they had already picked out the name “Jeff”), they had moved from their little garden apartment behind the Korvettes department store into our four-bedroom house in a new subdivision.

On weekends, my dad would take the three of us girls on “nature walks” through the backyard or on field trips to nearby farms. He ordered science kits from the Edmund Scientific catalog that arrived each month and that we would put together in our fluorescentlit basement, delighting in the whiff of danger surrounding our experiments with magnets and iron filings and chemistry sets and telescope lenses.

My dad was the one who insisted that my parents buy the piano that now stood in our living room. He had hoped to take lessons himself. But once my sisters got their hands on it, he never had a chance.

My mother took it from there. She was the one who made sure we found our way to Mr. K. She didn’t have much use for the piano herself. I never saw her so much as touch it, other than to dust it. As the only child of a prosperous ladies’ clothing store owner, she had grown up in an attached house in the shadow of the old Forest Hills Tennis Stadium and Clubhouse that hosted the U.S. Open tennis tournament each year, though she never went because Jews weren’t allowed to join. Her parents, striving first-generation Americans whose families had escaped Czarist Russia, had insisted that she take six full years of piano lessons, during which she learned only that she was tone-deaf. Her singing voice was so god-awful that as a toddler Michele, who had an excellent ear, faithfully learned to sing off-key.

But Mom did know that anyone who showed any musical talent in East Brunswick studied with Mr. K. And she was determined that her daughters would, too.

Mr. K’s reputation preceded him. His arrival in East Brunswick had coincided with my parents’ own. Not long after he started, he made headlines for creating a school orchestra, a rarity in a town better known for its 4-H livestock exhibitions at the county fair held each August down on Fern Road.

There hadn’t been enough musicians at first, not enough even to field a baseball team, much less an orchestra. To make sure they showed up, on concert days he tooled around in his big white Pontiac, collecting students along the way. His car was a familiar sight in the older section of town, where the homes were a little bit smaller and the driveways were empty. Passing the Colonial Diner and Two Guys on Route 18, Mr. K would turn off the highway and go house to house, honking, as screen doors banged open and students with instrument cases came flying across the lawns. When he’d gotten everyone, sometimes he’d stop off at his house and treat the whole lot of them to dinner with his own kids. Mostly, the students just toyed with the glutinous red borscht that, disconcertingly, always seemed to be on the menu.

He invited the best of them to study privately with him on school nights in his basement studio, where he sat on a piano bench with his tie unknotted and a ratty cardigan sweater thrown over his dress shirt, banging out notes on the keyboard.

His music program attracted a lot of attention—even more so after the concert where we watched his daughter Melanie play a solo. The newspaper that landed on our driveway every morning sometimes ran photographs of him with his daughter and her violin. I was intrigued by the little girl my age whom I’d never met and never heard speak, but who I had watched perform on the stage.

One of those articles showed a photograph of Mr. K with “Little Melanie, aged 5,” and “already a gifted young violinist,” as he helped her practice. The article said Mr. K had made East Brunswick into “a hot-house for young string players,” and that more of his students were accepted into New Jersey’s competitive student orchestras—All-County, All-Region, All-State—than any other town in the state. The article was headlined “Mr. Music” and it said Mr. K was called “the Santa Claus of Strings.”

I didn’t think Mr. K looked at all like Santa Claus. I had never heard the older kids call him that, either. I heard them call him other names—none that my parents would allow me to repeat—but Santa Claus was not among them. I thought, instead, he looked like one of the bad guys in the movie The Russians Are Coming! The Russians Are Coming! My parents had taken us to see it in a double feature with Bambi at the Turnpike Drive-In Theater out on Route 18, where I was allowed to play on the swings in my pajamas and fall asleep in the back of our station wagon.

Sometimes the newspapers printed the pictures of Mr. K’s conquering students, posing with their unblinking, unsmiling teacher in his dark suit and severe little mustache. He looked old to me—maybe even thirty—and when you peered at his face, an involuntary “Yes, sir” just popped right out of your mouth. Some of the students were shown mid-performance, their violins held high. Each one had the same ramrod straight posture, the left wrist held back smoothly, the right bow arm precisely angled, and the right wrist moving so fluidly that the bow seemed to glide back and forth like nature intended it that way.

You could see that my sister Michele, after playing for barely more than a year, already had the same elegant form. Her straight posture and firm wrist made her look just like the kids in the newspaper pictures with Mr. K. Someday Michele hoped she could get private lessons with him, too, not just the group lessons offered for free at school. My mom had already asked, but there was a year-long waiting list for a spot on his roster. And besides, he seemed unusually preoccupied these days.

I, meanwhile, was resigned to pretending to be a ballerina.

“Why can’t I play an instrument?” I asked my dad once again, as I lifted up my arms clumsily in a thoroughly unconvincing port de bras.

“Have patience,” he said, smiling. “Maybe next year.”

Left to right: Joanne, Ronni, and Michele Lipman at ages five, eight, and ten. Their dad, Burton Lipman, an avid photographer, was behind the camera.

MELANIE

“Get your keesters into the car!” Daddy yells at Steph and me. He is often impatient these days. I grab Stephanie by the hand, pulling her away from the half-eaten ham sandwich on her plate. Down the steps toward the garage we go, with a quick stop so I can pull an old towel from the linen closet in case she gets carsick.

On weekends like this one, my parents go hunting for a cure for my mom. They have found a doctor, hours away in Delaware, with an experimental treatment they hope will make her better, or at least prevent her from getting worse.

My mother had gone to lots of doctors before one of them finally figured out a diagnosis: multiple sclerosis, which, the doctor bluntly told her, had no treatment and no cure. She had to be wheeled out of the office the day he gave her the news, though she had entered it on her own power.

My parents don’t believe that there is no cure. There has to be. My mother is always trying a new vitamin or some crazy diet that she read about. When I ask her how she can bear to give up tomatoes or eat liver all the time, she just shrugs and tells me she would eat far worse things if they would help her get better.

“Even rattlesnake juice? Even dog poop?” I ask, trying to make a joke.

“Yes, anything,” is her solemn reply.

The physical therapist who comes to our house teaches me how to help with her exercises. I rotate her legs, pushing them back and forth like giant rolling pins. To stretch her hamstrings, I stand on the bed where she lies, propping up one of her heels on my shoulder and slowly walking toward her, pushing my hands down on her knee to keep it straight, while she moans in pain. But the therapy doesn’t seem to help.

The Delaware doctor offers the most promising treatment yet. I watch as Daddy hoists my mom over his shoulder, then carries her down the stairs to the garage. I run to open the door for them, Daddy huffing as he lumbers past, my mom’s legs flopping heavily against his stomach. In a few hours’ time, the Delaware doctor will greet them, ready with an injection for my mother’s spine. She’ll have to go for spinal shots every few weeks for the treatment to work.

I hear my mother whispering with my dad as he settles her into the front seat. The shots hurt terribly, she says. “It weel be worth eet,” he grunts, trying to maneuver her legs into position in the big white Pontiac.

On the road, my job is to keep Stephanie entertained and, above all, quiet. But no sooner has Daddy started the car than we hear, “I feel sick.”

Steph looks terrible. Her face has a greenish tinge. She has a sensitive stomach and hates almost every food except for hot dogs and peanut butter. She is three years old and barely eats anything, but somehow, whenever we get into the car, whatever she did manage to get down comes right back up.

Now she is wedged in the backseat, her little legs pressed tightly against mine, looking queasy even before Daddy pulls the car out of our driveway. Guiding the car down our street, he puts his foot on the gas and we lurch forward. Then he slams on the brakes and we jerk to a stop. He steps on the gas again, then stomps on the brake once more. The seats squeak as we stagger along like that while our necks whip back and forth, smacking the backs of our heads against the seat cushions. This is the way it always is. Daddy has never quite gotten the hang of American driving.

“I’m going to be sick!” Stephanie cries again, as we turn from our development onto the highway, lurching and screeching along the way. I try rubbing her back, telling her to think of flower gardens, her dolls, things that she loves, but I can feel her muscles tightening through her shirt. I already have the bath towel spread across my lap.

At almost six years old, I am a surrogate mother to my little sister. When Steph needs a Band-Aid pulled off, her temperature taken, or her hair combed out of a snarl, she turns to me. We were born twenty-seven months apart, and my earliest memory is of watching my breath make clouds on our living room window, my head barely clearing the windowsill, as I waited for my mother to bring Steph home from the hospital.

My excitement was tempered when Steph arrived, colicky and crying and monopolizing all of my parents’ attention. I tolerated it when my mom took care of her, but for the life of me I couldn’t figure out why Daddy should have anything to do with her. I was hurt and miserable when, after being sent to bed, I heard him sitting up with her, rocking her and singing to her. In the morning, I’d grab his legs when he was on his way out the door to work, begging him to stay and play with me. I wouldn’t let go until he pulled Pez candy from his breast pocket to distract me.

In the car, I look over at my sister, now clutching her stomach. She is everything I am not: dark-haired, dark-eyed, a mass of whirling arms and legs that seem to happily be everywhere except where they are supposed to be.

Steph’s clothes are perpetually disheveled, her toys always in disrepair. Her bright yellow bedroom is like a scene from a disaster movie: her floor is invisible beneath a kaleidoscope of crayons, colored paper scraps, plastic teacups, doll clothes, art projects, dirty laundry, and the strands of polyester hair she cut off from her dolls’ heads. “I need it all, Daddy!” she says when he tries to make her throw anything away. The top of her dresser is crammed with an infirmary of bald dolls with imaginary ailments whose symptoms are a lot like our mom’s. Steph lovingly bandages their legs and arms and heads with casts made out of Kleenex.

Most nights, Steph sneaks downstairs after dinner to the room outside my father’s studio to draw crayon pictures for his waiting students, or to entertain them with funny stories she invents about girls with long hair from normal families without foreign fathers or mothers in wheelchairs. Her tales are elaborately detailed, and she lingers over descriptions of birthday parties with pink layer cakes topped by princess crowns and gifts wrapped with satin bows. Daddy inevitably hears her giggling and opens his studio door to shout, “Stephanie! Get your keester upstairs!” Later, giving in to Stephanie’s pleas for a pet, he brings home a parakeet as a reward for cleaning her room. She promptly names it “Keester.”

People are always drawn to Stephanie. Harried parents rushing in to collect their students at night find themselves stopping to visit with her, and I hear them both laughing as if at some private joke. During my grandmother’s weekly phone calls, while I deliver dutiful responses of “Yes, Nanny. No, Nanny. Thank you, Nanny,” Steph flops down on the couch, props up her feet, and gushes, “Okay, Nanny darling, let’s chat!” Though she has ferocious temper tantrums—her little feet once kicked a hole in the living room wall—her tears are over in a flash, and soon she is giggling again, living up to her middle name, Joy.

I envy how easily Stephanie climbs up on Daddy’s lap, makes him laugh, and smothers him with kisses. How she draws pictures for him that he saves in his sock drawer. How she can get away with teasing him, something I wouldn’t dare try. When he is sick with a fever in bed for a few days while our mom is in the hospital, I set us up with picture books and sit quietly on the floor outside of his room. Steph brushes past me, impatiently bursts into his bedroom, climbs on top of him, and rubs her little finger along his unshaven chin, making up songs:

Meow goes the mustache

Woof woof goes the beard

I love my Daddy

Even though he’s weird.

Steph can’t hold anything in—not laughter, not love, not anger—and, at the moment, in the car, not her lunch, either.

“I’ve got to throw up!”

Daddy glares back at us, then tunes the radio to the classical music station and turns up the volume.

Sometimes the music helps Steph take her mind off her stomach. My parents are always playing recordings of the classics for us, though between my mother’s health and the expense, we can’t afford to go to live concerts. Daddy started us off with kid-friendly pieces like Tubby the Tuba and Saint-Saëns’s The Carnival of the Animals and then moved on to my mother’s favorite choral works that she used to conduct, excerpts from Haydn’s The Creation and Brahms’s Requiem. My mother especially loves Mendelssohn and Mozart. She always talks about the day I will play Mendelssohn’s Violin Concerto in E Minor, her all-time favorite and apparently some kind of milestone for budding violin soloists.

The only thing our parents won’t let us listen to is rock and roll. Anything but “that popular crap that eez called music, like the Bittles with their ‘Yeah, Yeah, Yeah,’ ” my father grumbles.

On the car radio, a Wagner opera fills the air.

“That makes me feel worse!” Steph wails, as an overwrought soprano reverberates through the backseat. Steph hates opera, even more than Daddy hates the Beatles.

And with a sudden lurch, Steph heaves into the towel spread across my lap. Daddy pulls the car to the side of the road and fumbles for the plastic bag we always have on hand just in case, and I deposit the dirty towel that I’ll wash with the rest of poor Stephanie’s sour-smelling laundry when we get home.

I crack open the car window as Steph gasps for air. Her face is already turning from green to its usual pink, her breath is steadying, her muscles relaxing.

It will all be worth it, of course, if the shots work.

But months later, my mother’s condition has only gotten worse. That is the last she sees of the Delaware doctor.

Kids hardly ever come over to our house to play. So when I’m not practicing violin, Steph and I make up games to play with each other. We imagine that we’re babies, crying for our imaginary mother to come running to take care of us. Our imaginary older sister is a doctor who gives us shots. The pretend shots are painful, like the ones our mom gets from the doctor in Delaware, but they will cure us from ills like growing up and dying.

One afternoon, after the daytime babysitter has left but before the evening sitter has arrived, Steph and I are deep into our game in the living room. I have just gotten my imaginary never-grow-up shot when my mother cries out from the upstairs bathroom. Steph and I run in to find her sprawled on the floor where she had fallen, between the sky-blue bathtub and toilet, her head jammed up against the bright pink tile. She is trying desperately to pull herself up, but there is nothing to grab on to.

Lots of times she gets stuck on her way into or out of the bathtub and has to call me to help lift her leg up and over the side. In fact, the only times I see my mother in an upright position are when I help her in the bathroom or to get out of the car. Later on, when I think of my mother, I always imagine her at seated height. I will grow up with no memory of how tall she actually is.

But this time is different. Steph and I are terrified to see our mother sprawled out helplessly on the floor. We try as hard as we can to lift her up, but her legs are just too weak. Her condition has deteriorated.

“Girls, I need you to run across the street to get help. Go, quick!”

Steph and I look at each other, a single thought shared between us both: No way. Uh-uh.

Not only are we scared to death of Missy, our neighbor’s vicious biting dog, but the family’s three boys have never missed an opportunity to tease and torment us. We certainly aren’t going to tell them our mother is at this moment trapped on the floor beside the toilet. We would die of embarrassment, and those kids would never let us forget it.

“Grab an arm,” I order Stephanie.

She takes one, I take another, and we pull with all our might. No luck.

“Try her legs!”

We try again, and when that doesn’t work, we tug her by the armpits. But my mother is wedged tighter than ever between the toilet and the tub.

There is no way we can get her into a standing position.

We have no choice. Steph circles her little arms around one of my mother’s legs and tugs, while I hug the other to my chest and pull, and we drag my mother by the ankles out of the bathroom. Across the worn brown carpeting we go, my mom crying and laughing at once, as we strain and pull her down the hall and finally into her bedroom, where she grabs the bedsheets and hoists herself on top of the bed. That’s where we all collapse in a heap until Daddy comes home and finds us.

My mother heads back to the hospital after that. “Just for a few days,” she tells us before she leaves. After the car pulls away, our babysitter shoos Steph and me out to the sandbox. It is a sunny June day, and we can smell freshly cut grass. My throat is tight and my breath catching as I sit, letting the sand run through my fingers.

“Hey, Steph,” I say, looking up from the pile accumulating at my feet. “Let’s make a surprise for Mommy!”

“Okay, what will we make?” Steph turns her little face up to me.

“Let’s make a sand castle, and write ‘Welcome Home’ in the sand so she can see it when she comes back.”

By the time she gets home it is winter. Eight months have passed. Our sand castle is long gone, and the sandbox is covered with snow.

Every August, almost all of my dad’s older students go to the music camp he runs at Douglass College, just down the highway from our house. The American String Teachers Association, or ASTA for short, holds a weeklong conference of orchestra and chamber music during the day and concerts and recitals at night. Students stay in bunk beds in the Katzenbach Hall dormitory and eat at the cafeteria where you can get as many bowls of wobbly Jell-O cubes as you want. At seven years old, I am years younger than most of the other campers. But with my mother in the hospital, Daddy ships Stephanie off to stay with Grandma Brown and takes me with him.

“Dance!” Mr. K commanded his students at the New Jersey ASTA Conference get-acquainted party. Here, he takes matters into his own hands, circa 1969.

My roommate, a thirteen-year-old viola player named Jeannie, lets me tag along with her to rehearsals and meals so I don’t get lost. On the first night, she brings me with her to the “get acquainted” dance, where girls in short dresses and patent leather sandals stand on one side of the room, while boys with shaggy hair drink punch on the other. The high school jazz band is playing “Take the ‘A’ Train.”

My dad strides in, his white socks flashing underneath his dark suit. I hear tittering all around. I can’t figure out why. Then I see: He has marched over to the boys’ side and is dragging one boy by the hand to a girl across the room. He puts their two hands together and commands: “Dance!”

They don’t dare disobey.

Now he is back on the girls’ side, grabbing the hand of a quiet brown-haired girl in a sleeveless lace dress and dragging her out to the dance floor himself: “Let’s show them how eet eez done!”

My dad loves to dance. I’ve never seen anyone else move like him. He jerks his legs and kicks up his feet like a drunken Cossack dancer. His movements don’t seem to relate in any way to the music, not to the speed or the beat or anything else. The kids scream in laughter and applaud. My dad kicks up his feet even higher. His toes trace awkward angles in the air. I’m glad he hasn’t dragged me onto that dance floor. But I can’t help thinking he looks happier than I’ve seen him in a long time.

At ASTA, I have my first audition. I play my solo and scales in front of a couple of music-teacher judges in a classroom. Later, they post the results on a sheet of paper in the hallway. The other kids run to the wall and madly search for their names, jumping up and down to get a look over other people’s heads, then screaming in excitement if they’ve done well or slinking away angrily if they haven’t.

I don’t care. I have yet to learn that the world of student orchestras is one of hierarchies on top of hierarchies. There are tryouts to get in, then placement in either first or second violin sections, then rankings from first chair to last. If you are seated in the front near the conductor you must be good; if you are seated in the back you must be plain awful. The stigma attached to being placed in the rear of the section is devastating.

It will take years before I understand the gravity of the seating chart. That summer, I place into the intermediate orchestra, in the middle of the violin section. I am too short to see the conductor, blocked by a thirteen-year-old boy in front of me.

“Hey, Gordon. Switch seats with Melanie,” the conductor calls over to him casually. “She can’t see over you.”

Gordon looks stricken. “Everyone will think she beat me in the audition!” he erupts. During the break, I hear him tell his friends: “I’m going to challenge her. Then the conductor will have to give me my seat back.”

The dreaded challenge. I’ve never heard of it, but it doesn’t take long for Gordon to explain it to me. We will both perform an excerpt from the orchestra music, alone in front of the group. Whoever plays it better wins. The conductor agrees, and the challenge is on, scheduled for the following day.

After the rehearsal, seeing my dad across the room, I run up to him and fling myself into his arms.

“Daddy! A boy challenged me! I have to learn a part of the orchestra music and play it alone tomorrow!”

“What? Calm down, now. Who challenged you?”

“Th-th-that boy over there!” I point. Gordon is standing across the room, laughing with his friends.

I wait for the warmth of Dad’s sympathetic hug. I wait for him to tell me that this isn’t fair, that he won’t let some boy pick on me. Daddy will fix it, I’m sure.

Instead, he grabs a music stand, sets it up right there in the corner of the room, and tells me to start practicing.

For fifteen minutes, my dad watches over my shoulder as I work on the piece, barking orders. “More bow!” “Intonation!” “Watch your rhythm!” Then he dispatches me: “There, now you just go out there and play like that. And may the best man win.”

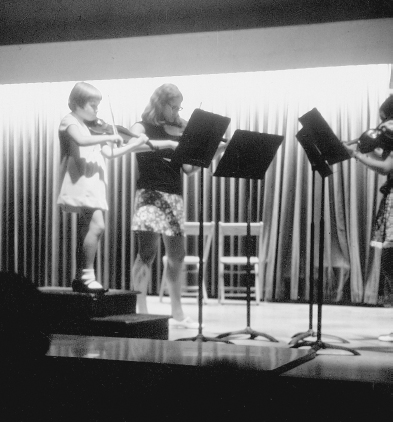

Melanie’s first chamber music performance at age seven, standing on a podium. Michele Lipman plays the violin across from her, in partial profile.

Maybe I should have expected as much. When we play checkers or Parcheesi, my dad always wins. He says if he eased up and let me win, that would be cheating. It’s one of the first lessons I remember from my father: Work hard, but don’t whine if you lose. And if you do lose, pick yourself up and try harder next time.

In the end, Gordon backs off from the challenge when he figures out I’m Mr. K’s daughter. My dad solves the problem anyway, placing my chair on a box so I am tall enough to see over Gordon’s head.

I stand on boxes a lot these days. My first ASTA chamber music performance is in a violin quartet with three teenage girls. One of them is a pretty thirteen-year-old violinist with straight brown hair named Michele. She’s from East Brunswick, too. She wears little denim cutoff shorts during the day and white Mary Janes and lacy minidresses when we have to dress up for concerts. That afternoon, I’m wearing a Sears catalog dress my mom ordered from her hospital room, and my dad has made a mess of cutting my bangs.

While my dad searches for a podium for me to stand on, Michele eagerly scans the audience, pointing out her parents, who sit waving in the front. Alongside them sit her two sisters, the smaller one a girl about my age named Joanne, who has a book in one hand and looks bored.

I am the first violinist, which means I’m supposed to lead the group. As we begin our piece, I look up at the others every once in a while to make sure we’re all playing together. Each time, Michele smiles reassuringly back at me. When we finish, the audience applauds enthusiastically, Michele’s family loudest of all. I can see my father in the wings. He isn’t clapping, but he looks satisfied.

I gaze out from the stage, the last chords of the piece still in my head. My mom isn’t here—nothing can change that—but so many other familiar faces are, smiling back up at me. It’s a wonderful feeling, like an embrace, and relief and happiness. And belonging. There is no better feeling in the world. I want it to last forever.