10

Stage Fright

JOANNE

In my old photo album, there is a yellowing snapshot of me at age fourteen, all knobby elbows and frizzy hair and glasses, painfully skinny in a purple gown, the very picture of excruciating adolescence. I am standing awkwardly in my family’s front hallway, my cough-syrup-colored dress clashing with the brown-striped wallpaper behind me. Yet in the photo, I have a huge grin on my face.

I remember the moment exactly. After my disastrous youth orchestra audition, I had developed a horrendous case of stage fright. I froze up every time I had to play for anyone, even for my sisters or my parents. If my mother so much as spoke on the phone while I was practicing, my hands would start to tremble and my bow arm would seize up with fear that the caller might overhear me, the notes croaking and the music sounding like a dying frog.

Alone, I practiced for hours, advancing steadily through the standard repertoire: Telemann Concerto, Reger Sonata, Bach Cello Suites transcribed for viola. But when anyone was listening, even Mr. K at my lessons, the dread that started in the pit of my stomach ballooned like some sort of monstrous tumor, taking over my muscles, my nerves, my organs, until it squeezed out every iota of music in my body. I was paralyzed.

The first audition after my tryout trauma was for Senior Regional Orchestra, a qualifier for All-State Orchestra. I was supposed to be a shoo-in for principal violist. But when I woke to the insistent ringing of my alarm clock that morning, my head felt like it was being pinched between pliers while simultaneously being suspended upside down on a broken Ferris wheel—the kind my mother had warned me about years ago. My eyes refused to focus. When I sat up, my body lurched forward while my brain sloshed backward. I pulled off my lime-green covers and stumbled toward the bathroom, but before I could get a look at myself in the mirror, I fell to the floor in a dead faint.

My parents found me there, crumpled on the linoleum tile next to the washing machine. After much whispered discussion and desperate entreaties from me after I revived—“I feel fine! I can’t miss the audition!”—they allowed me to go. But they both came along, insisting that I lie down and rest in the leather backseat of my dad’s brown Oldsmobile 88 on the way. They kept watch over me while I warmed up and then sat outside the audition classroom when it was my turn, as if they were holding vigil for an accident victim in an emergency room corridor. Afterward, they took me to the doctor. Diagnosis: nerves.

I was too embarrassed to admit my fear to anyone, especially my intimidating teacher. Mr. K never acknowledged that he knew my secret. If he noticed my cramped gait and sweaty palms, he didn’t let on. But one day not long afterward at my lesson he announced, “You weel play solo at next orchestra concert. Eet eez all arranged.”

He pulled out one of my favorite pieces, Tema con Variazioni, a pretty Renaissance-era work composed by Marin Marais, a court musician at Versailles. The piece wasn’t originally written for viola—not much is—but it had been transcribed by Paul Doktor, the violist I idolized and followed around like a groupie. His autograph was one of my prized possessions.

The day of my solo performance, I woke up with creepy silent fireworks exploding in front of my eyes, splashing garish splotches of color anywhere that I tried to focus my gaze. I took deep breaths to calm myself before gingerly stepping out of bed. I forced myself to choke down an English muffin. After showering, I spent two hours trying to tame my hair into submission. My arms were shaking while I maneuvered the lime-green blow-dryer and stared back at the fearful reflection in the mirror in my bedroom.

When we pulled into the high school parking lot, I smoothed my purple dress, pulled back my shoulders, and pretended to feel a confidence I didn’t remotely possess. I pushed through the rehearsal room door, viola case swinging behind me. Mr. K greeted me with a hug.

The concert featured the orchestra playing typical Mr. K music, heroic and patriotic and celebrating the triumph of right over might. After Richard Rodgers’s World War II–inspired “Victory at Sea,” I quietly stood up and headed to the wings to prepare for my piece.

Backstage, I felt my bravado crumbling. I paced back and forth in the wings, unable to concentrate on the Mozart echoing through the auditorium now. The increasingly familiar feeling of panic set in. I could taste bile in the back of my throat.

That was when I felt an arm slip around my shoulder.

“Shh,” Mr. K said. “You worked hard. You are well prepared.”

His left arm firmly encircling me, his right hand holding my own, he fell in beside me, matching the rhythm of my pacing, whispering in singsong in my ear.

“You weel have fun. You weel go out and have a good time.”

Back and forth we paced in the wings. In the distance, a string quartet was playing onstage. Beyond the footlights, hundreds of pairs of eyes were watching, paper programs were rustling, a few muffled coughs were echoing faintly from the back rows. But backstage, it was just the two of us. It was just Mr. K and me now. My own face felt rigid with fear, but when I looked at his, I saw serenity. Certainty.

“Shh,” Mr. K said again.

Onstage, the group before me was finishing up, and applause filled the hall.

With a gentle nudge, Mr. K propelled me from the wings.

“I’m proud of you” was the last thing he said, looking into my eyes as I drifted away.

From the front of the stage, I looked out at the full auditorium. I had that feeling of approaching the very top of a roller coaster—when you hear that ominous click click click click sound on the tracks before you plunge into a free fall. The taste of bile was making a return appearance in my mouth. Whenever I was at an amusement park and heard that click click click click of the roller coaster, I always looked frantically around for an escape route, reeling at the dizzying sight of trees and people on the ground and concession stands all receding into tiny primary-colored plastic toy figures. Can I get off?

I couldn’t. There was no turning back now, only going forward.

I plunged in.

For the first few notes, I was excruciatingly aware of every twitch of my muscles and every throat being cleared in the audience. But very quickly, Mr. K’s words came back to me, pushing away the fears and helping slow my panicked heartbeat. He believed I could do this. He was sure of it. He had confidence in me. I was ready.

This was the good kind of roller coaster, not the kind that spits unsuspecting kids into the ocean. It was hard work, but it was… fun.

When the piece was over, a wave of relief washed over me, rushing like white-water rapids in my ears so loudly that it drowned out even the applause. As I bowed to the audience, the way Mr. K taught me, I caught sight of him off stage. He was handing a bouquet of flowers to Ronni, who ran onto the stage to present them to me. I threw my arms around her. As I hugged her tight in joy and relief, I could see Mr. K over the top of her shoulder. He had stepped out from the wings to lead the applause.

At home just after the concert, my dad snapped the photo of the awkward, skinny girl in the purple dress with the huge smile on her face. She has frizzy hair and glasses, and the color of her dress clashes with the striped brown wall behind her. She is holding a huge bouquet. It is the first time anyone has ever given her flowers.

The picture is of a girl who has just gotten her confidence back.

Somehow, despite fainting just before the audition for regional orchestra, I had scored well enough to be named principal violist. Not long after, though, I landed in another youth orchestra, this one conducted—in a cruel twist of fate—by the audition judge who had so effectively tortured me.

Like the church, student orchestras hone to certain traditions from which they never deviate. They rise in unison at the conductor’s command. They show appreciation not by clapping but by tapping bows on music stands or stomping feet. And at the end of the final concert, the concertmaster presents a gift to the conductor and makes a short speech of thanks. Usually, that last task fell to Melanie. But Mr. K took me aside after rehearsal one day.

“At the performance, you weel geeve conductor flowers and make speech,” he said.

“But that’s Melanie’s job.”

“She won’t mind.”

“But the conductor hates me!”

“Exactly.” He nodded.

On the way home, when I explained the plan to my dad, he broke into a grin.

“Mr. K is right, Jo. Take the high road,” he said, glancing back at me from behind the wheel of the Olds 88.

Mr. K’s plan clearly appealed to my father. As a kid, my dad had stayed in the Boy Scouts all the way through high school. He reminded us regularly that he would have made Eagle Scout if only his parents had sprung for the swimming lessons he needed to complete that last badge. Barely a day went by when he didn’t cite the Boy Scout motto “Be prepared.” He believed in hard work and dedication. But he also was a skilled negotiator in business, who understood that graciousness, properly applied, was the ultimate expression of power.

A few weeks later, when I took my place onstage for the final concert, I was prepared, all right. I quietly slipped off into the wings before the last number, noticing the look of consternation mixed with suspicion on the conductor’s face. When I reemerged, I was cradling a bouquet of long-stemmed roses in one arm. I faced the audience, threw a smile in her direction, and launched into my prepared speech.

“There is no one else quite like our conductor…” I began.

I went on to thank her, on behalf of the whole orchestra, for the “unique” experience she had given us. “Personally, she has taught me so much,” I added, looking away from the audience to gaze directly into her eyes. My eyes locked on hers, and I spoke my next words slowly. “She has set an example that I know I will never forget.”

She shifted uncomfortably on the stage.

I turned back to the audience. “Ladies and gentlemen, please join me in acknowledging our conductor. She is really something.”

I presented the roses to the conductor and gave her a hug. When I stepped back, she was smiling graciously for the audience, but her eyes were wary, like a German shepherd that’s been cornered by a kitten.

After the concert, my parents came to find me, embarrassing me with big affectionate kisses planted on both cheeks.

“Good for you for taking the high road,” my mother said.

Backstage, as I was packing up, Mr. K had a big old mischievous grin on his face. He used a different expression to describe my performance, one that I had never heard before. So later, at the ice-cream parlor for a post-performance celebration, I asked my parents between spoonfuls of a hot fudge sundae with no nuts and extra whipped cream: “What does it mean to be ‘a wolf in sheep’s clothing’?”

That year, it seemed like the quartet was performing every week. There were few opportunities Mr. K wouldn’t consider. In my room at night, I carefully cut out and pasted into my photo album scores of newspaper articles, with such notable entries as this one from November 1975: “An ecumenical group of four young girls provided the patients of Villa Maria with a string concert on the eve of All Saints’ Day.”

I played at funerals, weddings, and every school in town. Once, Mr. K bused the orchestra to downtown Newark, where a hostile audience of inner-city school kids drowned out the music with shouts and jeers. Another time, I played at a New Jersey polka festival where a sleazy promoter tried to pass off recordings of our group as an “internationally famous polka orchestra.” My illicit favorite as a nice Jewish girl was performing the Hallelujah chorus each year at midnight mass at Our Lady of Lourdes Roman Catholic Church.

“You just can’t teach children an instrument and then hide them in a hole,” Mr. K explained.

Most of all, Mr. K made us perform in nursing homes and hospitals. These were well-meaning sorts of places, and they attempted to be cheery, with cardboard cutouts of candy canes and Santa Clauses around Christmastime and jack-o’-lanterns near Halloween. But the decorations couldn’t mask the air of futility that wafted through the halls, an aroma equal parts disinfectant and despair. We had to perform loathsome old-people musical standards that would make my stomach churn—“Begin the Beguine,” “Moon River”—in fluorescent-lit rooms filled with ancient women with thinning wisps of hair and decrepit old men in wheelchairs or leaning on walkers.

“Slush museek,” Mr. K called it. It made me a little bit nauseous.

The first time I performed at a nursing home, with the school orchestra, Mr. K stood up from his seat at the front of the yellow school bus as we rolled into the parking lot. He planted his feet shoulder-width apart, blocking the aisle, cutting us off from the door. We were trapped.

“Seet down,” Mr. K yelled. “You keeds don’t move yet.”

Whatever we had done, we were in trouble now.

Then he launched into a speech I would hear him give probably a dozen more times.

“Don’t be afraid,” he said.

We looked back up at him, puzzled.

“They going to want to talk to you, and touch you or hug you or kiss”—it sounded like kees—“you.”

Really?

“Let them. They don’t see a lot of young people.”

Mr. K told us some of the patients inside were old and others were sick, near death. Some of them were senile. We might be repulsed by what we saw inside. Too bad.

“After concert, you weel stay and circulate. And you weel like it.”

Then he turned and trotted off the bus.

Resolutely, we filed off, clutching our instruments and taking a deep breath of fresh air before plunging into the sour-smelling, linoleum-tiled all-purpose room.

As promised, the crowd was needy. No sooner had Mr. K lowered his baton on the final notes of “The Girl from Ipanema” than gnarled hands began grabbing at us like something out of the graveyard scene from the movie Carrie. I shrank away from an old woman clutching at me from a wheelchair. Out of the corner of my eye, I saw Mr. K. He was staring at me, his expression hard.

With a glance back at him, I forced a smile and approached the old woman. She told me I reminded her of her granddaughter and stroked my cheek. I could see Melanie and Miriam and Stephanie, too, circulating slowly among the old and the ill, Mr. K’s words seared into our brains even as they patted us on the head or cooed at us. The prospect of Mr. K’s wrath was without a doubt much scarier than the old people were.

We only stayed a few minutes before Mr. K called for us to get back on the bus. But the next time we went to play there, and with each time after that, I could have sworn we stayed progressively longer. The trips would continue regularly for years. Mr. K was always packing us off to some old folks’ home or hospital or rehab center. I wouldn’t admit it out loud, but I began to look forward to the conversations afterward with war veterans and old ladies who reminisced about their lost youths.

Each time, Mr. K gave us the same lecture, refusing to let any of us off the bus before he said his piece. “They’re going to want to hug you… Let them.”

On one of those visits, I noticed a new resident among the crippled bodies and gnarled hands. She was younger than the others. Her metal wheelchair was secured with a brake, and her body leaned at an awkward angle against its right armrest. She was Mr. K’s wife.

MELANIE

The weeks turn into months; the months turn into a year; and still my mother is in the hospital. I only realize how long it’s been when All-State auditions roll around again.

When the results are posted, I have to check twice to make sure I’m not misreading the list. There it is, in black and white: I am named assistant concertmaster.

Second place.

My dad holds me on his lap in the big brown easy chair in our living room while I cry so hard that my tears soak his shirt and tie.

I never realized I would care so much about losing an audition. The thought of disappointing him is devastating. Disappointing myself, though, comes as an even bigger shock. I didn’t practice enough, I silently berate myself. I didn’t measure up. I didn’t do what I was supposed to do. I was too sloppy. I didn’t work hard enough. I had no discipline. How could I have been so lazy? I’ve let everybody down. The familiar old cocktail of self-recriminations and guilt overpowers me.

He holds me for a long time, stroking my hair and saying little.

“I know you tried your hardest. Shhh. It’s okay, Lastivko.”

He hasn’t called me that in years.

I look up at him, sniffling. “You’re not m-m-mad at me?”

“Mad at you? Of course not!”

“But I made it last year, and I gave it up.”

“That was the right thing to do. You ween some, you lose some. You weel audition again next year.”

He straightens his tie and pats his wet shirt with the handkerchief from his pocket.

“Now, no more crying. Discipline yourself.”

My dad surprises me again when he allows me to go to the ninth grade dance with a boy. Michael Grossman is the cutest boy in the orchestra. I’m not his first choice, but I don’t care.

Michael and I will go on to date all through high school. My dad allows it only reluctantly. “Do not trust heem,” he often says of teenage boys, “but do not let heem know you do not trust heem.” Of course, my dad has a point. Michael and I sneak into the empty auditorium to be alone at lunchtime. Once, I steal the key to my dad’s office while he’s away so we can use it for a make-out session. We steam up the windows of Michael’s parked car, getting caught by the police in both of our neighborhoods.

Our boldest plan comes when my dad is out of town, Stephanie is away, and I decide to make a romantic dinner at home. We plan the evening carefully. Nothing too momentous—we are not ready for that yet, or at least I’m not—but we’ll have the whole house to ourselves for a few hours, until Michael’s curfew.

After I make the chicken and potatoes and put brownies into the oven, I decide it would be quite grown-up to have a drink before dinner, like I’ve seen my dad do countless times. So I pour myself a glass of vodka, straight. Michael will be arriving soon, so I figure if I have a big drink it will take effect faster. It tastes awful, but I quickly gulp down about a half cup of my dad’s Smirnoff. Wow! How can people drink this stuff? After just a few minutes, when I don’t feel anything, I repeat the process.

The next thing I remember, I am lying on the blue linoleum bathroom floor. I open my eyes. Where am I? What happened? Michael is there, and for some reason our music teacher Sandy Dackow, who works for my dad, is there, too. My nose is assaulted by the smell of vomit and burned brownies.

“It’s okay, it’s okay, you did the right thing to tell me,” Sandy is saying to him. “If she threw up, then she’ll be okay. Do you know how much she drank?”

Reassuringly, Sandy is her usual self, in charge and quick thinking. I close my eyes as wave after wave of nausea passes through me. I am lucky I didn’t die of alcohol poisoning, though I almost wish I had. Can you die of embarrassment?

I try to focus on Sandy’s face. She has become not just a teacher but also a close family friend. But she works for my dad; isn’t it her duty to report back to him?

“Please don’t tell,” I murmur, before succumbing to another surge of nausea and guilt. I don’t think she will. She’ll be just as afraid of his reaction as I am.

My dad keeps lining up solo performances for me, but the older I get, the more I dread them. I wish I could conjure up the childish fearlessness I used to have, before I was old enough to understand stress and anxiety.

Orchestral playing, on the other hand, has exactly the opposite effect. It’s exhilarating. I can plug into the energy surging around me and lose myself in the music. It offers an escape from the loneliness of my practice room and the solitary pursuit of solo playing. It’s a way to connect with my fellow musicians, to become part of something greater than me. I’m fourteen years old the first time I realize it. At an All-State Orchestra rehearsal of Wagner’s triumphant Overture to Die Meistersinger von Nürnberg, just before the climactic cymbal crash near the end, I glance down to see goose bumps rising on my arms. My scalp is tingling, as if my hair is sticking straight up. When the music stops, it takes a moment before I am earthbound again. I am surprised to find myself in a folding chair in a school rehearsal room in New Jersey. I just want to keep doing this, over and over again, for the rest of my life.

Teaching music is almost as good. I’ve been helping my dad since I was twelve years old. He always enlists the aid of more advanced students to help less advanced ones. At first my job is to help the beginners, putting marker tapes on fingerboards and bows and patrolling through the violin section, pushing down left wrists and helping the kids arrange themselves with their violin scrolls pointing inward so they won’t whack each other with their bows.

By the time I reach high school, my job also includes demonstrating difficult passages. Sometimes my dad makes every violinist in the orchestra play alone, in turn, and when someone has trouble, he makes me play along.

“Who eez deaf een first violins?” he yells one day, as he often does. It’s a rhetorical question, but this time a hand is sheepishly raised from the back of the section.

“I don’t need to know! I just want you to fix eet!”

My dad beckons me to stand behind Ted Kesler, in the back of the first violin section. Together, we play the passage again and again, while the rest of the kids in the orchestra wait patiently. Ted grimaces, but he is used to this by now. My dad spends extra time on the kids like Ted who he thinks need the most help. He may not show it, but I’ve learned over the years that the underdogs are the ones whose progress fills him with the greatest pride.

Sometimes I feel as if my dad is testing me, too, to see how much I can take. Once, when the violins are fumbling a passage from Aaron Copland’s “Hoe-Down”—an orchestra favorite—he threatens to pull the piece from the program unless I stand and play it perfectly. The room goes dead quiet. I can see a cellist crossing her fingers, eyes closed. When I do manage to play the passage to my dad’s satisfaction, I feel as if I’ve scored the winning goal just as the buzzer is about to ring.

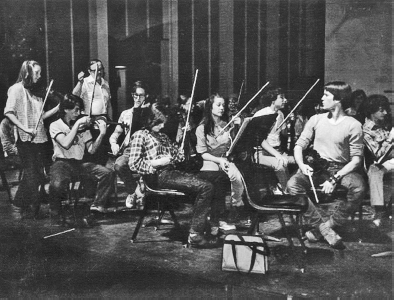

“Who eez DEAF in first violins?” Mr. K solves the problem by having Melanie play along with students, including Ted Kesler (seated at left), while he keeps the beat. In front of Ted sits Stephanie Kupchynsky. At far right, watching Melanie, is Michael Grossman.

Another time, after a particularly trying rehearsal, my dad tells my mom, “You know, I was pretty tough on Melanie today een front of the whole orchestra. I gave her a really hard time. Probably a leetle too hard. And she never reacted, never got upset. Just smiled and deed what I told her.”

“Daddy,” I say, looking him straight in the eye, “that was not a real smile. That was controlled hostility!”

My dad laughs and looks at me with new appreciation. Behind the amusement I can see a hint of pride—and respect.

You wouldn’t think a mother’s absence, her lingering stay in a hospital, should ever feel normal. But over time, to Steph and me, it does. It’s just the way things are. I’ve already been doing the cooking and cleaning for some time. I tend to my dad’s Qiana shirts the way he likes, hanging them up still warm from the dryer and buttoning the top button to make sure the collar lays properly. I wash and fold my mom’s laundry from the hospital, then return it to her when we visit. I learn to make cheese sauce to cover the taste of the vegetables Stephanie hates. I clean the house each week, then bake brownies as a reward, then yell at Daddy and Steph for tracking crumbs all over my spotless kitchen floor.

Stephanie, now in middle school, just smirks. She is preoccupied with a new group of friends who sometimes come by the house when my dad isn’t there. They smell like smoke and look at you with narrowed eyes. They wear dark clothes and thick black eye makeup. Steph’s best friend scares me the most. She is long and lanky and has an evil look about her. I’m sure Steph is telling her friends things about me that aren’t true.

After my dad leaves the house in the morning, Steph changes into pants he thinks are too tight and lines her eyes with kohl. When I collect her laundry, sorting through her piles of black clothes, I find unsettling clues about the life she is no longer sharing with me. I uncrumple the scraps of notebook paper that I find balled up in her pockets and read the scrawled notes that she and her friends have been passing back and forth to each other in class.

“I hate everything.”

“My life sucks.”

“Homework is a joke.”

“I’m SO bored.”

“My parents are assholes.”

“I have to get out of here.”

It’s confusing; I don’t know what to do. When my mother was in the house, Steph and I were aligned, a unit, each other’s greatest defender. But since my mom has been in the hospital, I’ve had to act as Steph’s caretaker instead. I can’t be her ally anymore. She’s my responsibility now. The strain between us is unbearable, and we fight more than ever. Most of what Steph is up to is uncharted territory for me anyway; I don’t have the benefit of having “been there, done that.” I have no idea what I’m supposed to be doing to help her.

If I tell my dad, he’ll just get mad. I don’t want to worry my mom, whose condition is aggravated by stress. Nor do I want to make Steph mad at me.

But I can’t just let it go.

One night after dinner, I bring up the subject after my dad goes downstairs to his studio.

“Uh, Steph? I was thinking. What ever happened to Chrissie and Arlene? And Liz? They were so nice, nicer than your friends are now…” I trail off.

“What’s wrong with my friends?”

“I don’t know. They’re a little scary. Tough. Smoky.”

“They’re my friends. They care about me!”

I back off. “Sure, I know. I just wondered, you know, about the other girls?”

“They’re dorks!” she announces, leaving the room.

Steph’s grades start to slide as she falls in with the girls who smoke cigarettes in the field behind the school and cut class. At first it’s easy for her to keep my dad from seeing the warning notes that come in the mail. She simply throws them out before he gets home. It’s trickier to keep her report cards a secret, but she’s able to fool my dad by painstakingly changing the D’s to B’s, or F’s to A’s.

One day I see her report card lying on the table. As I pick it up she grabs it from my hands.

“What are you doing? That’s mine.”

“I know, I just wanted to see. What did you get?”

“Well, if you must know, I got a bunch of B’s, and one C. And one D.”

I inhale sharply. A D! “What did Daddy say? Did you tell him yet?”

“No, and I’m not going to. I can bring it up next quarter.”

“But he has to sign your report card! He’ll see it!”

“No, he won’t. Look.” She has neatly forged his name in the space provided. It doesn’t really look like his writing, but I have to admit I’m a little impressed by how bold Steph is. I say nothing to my dad and hope for the best.

Of course Stephanie and I are both kidding ourselves. My father is a teacher, and one who knows every other teacher in the entire school system. He practically explodes when he finds out what is going on.

“Stephanie! You are failing math! How eez this possible? What the hell eez going on?” He is yelling so hard his face turns purple, and I’m afraid he’ll give himself a stroke.

My dad can’t figure out why any daughter of his would squander the chance to get an education. To him, nothing is more important. He’s saved every one of his own report cards, even the ones from when he was a boy in Ukraine during the war. His framed diplomas hang on the walls of his studio.

“It’s not fair!” she cries when I sit down with her that night to go over her homework.

Dad stomps angrily down the steps after dinner to teach, leaving me with my sullen sister, her teary face smeared with eyeliner that she isn’t supposed to be wearing in the first place. I’m the enforcer now.

Though Steph doesn’t confide in me anymore, I can hear her thoughts when she practices the violin. Longing, sadness, anger, melancholy, all of them come through in the strains of her playing. Our vicious old great-aunt Titka, who scares me almost as much as her sister, Baba, is right when she remarks: “You, Malanka, play with energy. But Stephka—she plays with heart.”

Sometimes I see glimpses of the sweet, funny little girl behind the eyeliner. But those flashes appear less and less frequently. In eighth grade, Steph develops a cough and hoarseness that will not go away. My dad is worried. “Thees eez what comes from not eating your vegetables!” he says, insisting she eat more greens. Every time she leaves the house, he calls after her: “Bundle up!”

Only after he discovers a hole in the window screen of the downstairs bathroom and a little pile of cigarette butts underneath does he realize the reason for her cough. His feet come pounding up the stairs and down the hallway to her room, and another round of screaming, ranting, and threatening ensues. He’s running out of weapons, of things to take away. She is already grounded and forbidden to use the phone. At his wit’s end, Daddy extends her sentence. She’s now grounded indefinitely. But none of the punishments seem to make any difference to Stephanie.