14

The Gig

JOANNE

When I landed on campus freshman year of college, I knew where I wanted to go. I knew I wanted to become a journalist. Unfortunately, I knew very little else.

My first day of class at Yale, I watched classmates reciting—by heart, in the original Middle English—the prologue to Geoffrey Chaucer’s The Canterbury Tales, a book I hadn’t heard of. Everybody in beginner French already spoke fluently. The psychology professor yelled at me for nodding off, as it turned out from a raging case of mononucleosis, during his lecture on B. F. Skinner.

The only subject for which I felt well prepared was viola. I qualified for graduate-level lessons at the Yale School of Music with another one of my viola heroes, Raphael Hillyer. Mr. Hillyer was a formidable presence, the founding violist of the renowned Juilliard String Quartet. His demeanor was intense and his pedigree daunting: Curtis Institute, Dartmouth, graduate studies at Harvard, where he gave recitals with his friend and classmate Leonard Bernstein. When I showed up with a sky-high fever from the mononucleosis and dragged through my lesson, Mr. Hillyer had no sympathy.

“I suggest you warm up before you arrive,” he said drily, not inviting further comment. I suspect he wasn’t interested in hearing about my fever convulsions the night before.

Between practicing and symphony rehearsals, I spent more time on music than on the school newspaper. Still, there was an addictive pleasure to sitting in the musty Yale Daily News offices, in a paneled room hung with formal portraits of the all-male editorial boards of decades past, tapping out stories late at night on a typewriter. I would stay until dawn, gorging on other people’s leftover cold pizza and then heading in to the composing room. There, the pages were laid out on easels, and the editors literally cut out pieces of articles that needed to be fixed using razor blades, then pasted the new, corrected versions on top.

After my Yale Daily articles were put to bed—as my mother insisted, I always asked a Responsible Boy to walk me back safely to the dorm, in this case a Responsible Boy being anyone still standing at five A.M.—I would grab a few hours of sleep before class. Then in the afternoon, I would carve out time to practice, turning down the Crosby, Stills, Nash & Young that my roommate Carol and I usually played on the stereo while we studied.

My goal in college was to get a summer internship at the Wall Street Journal. My father had read that paper every day since before I was born. It landed on our driveway at home while it was still dark out each morning. He loved the excitement of the business world; he always said that it was “an adventure.” As a kid, I never looked at it. But the summer after freshman year, I won a magazine internship in New York City and commuted on the bus every day with my dad. Out of boredom and desperation one morning, I picked up his newspaper. I was transfixed: the front page had the best writing I had ever read.

That first magazine internship had been humbling. At my job interview, when I closed up my slit-front skirt over my knees, the interviewer barked, “If you want the job, you’ll leave that open.” My boss, the editor in chief, gave me assignments like buying presents for his wife. Still, I managed to report and write several pieces. That was enough to get me a job the following summer as a “copy girl” at my hometown newspaper, the Home News, where I would run to the printing press when it started rumbling and deliver the first copies to editors in the newsroom.

An internship at the storied Wall Street Journal would be a long shot. But junior year, I sent my article clippings anyway. Weeks later, I was surprised and a bit terrified to learn I was a finalist, invited with other aspirants to a lunch with editors in New York. This would be my most important audition yet.

At the Journal office, in a conference room set up with sandwiches and cans of soda, I met the judges—a small group of editors and reporters—and was introduced to the competition: about a dozen other students, one more intimidating than the next. They had interned at fancy places like Time and BusinessWeek. They casually dropped business buzzwords into their conversations and nodded knowingly at the jargon the Journal reporters in the room tossed around with ease.

But looking around, I realized something. Unlike at an orchestra audition, I wouldn’t be called into a closed room and asked to play scales by people with pencils and judgmental expressions. I didn’t have to worry about shaky arms or cramping fingers. I didn’t have to fret that my muscles might betray me. The overwhelming pressure of viola auditions, and Mr. K’s years of putting me through hell, made everything else seem easier by comparison. Once that realization struck, my fear receded.

As the bureau chief gave us a tour of the newsroom, I peppered him with questions. How did the news ticker work? Why was he so interested in the story that broke during our tour, about AT&T breaking up? I worried that I was asking too much, betraying how little I knew. But a few days later, a letter arrived: I had made the cut.

That summer, I threw myself into learning how to write earnings reports, cover shareholder meetings, and pitch story ideas. One of my pieces even made the front page. I didn’t have a spare moment to practice my viola.

Back at school in the fall, my Journal boss called to offer me a job as a bona fide reporter, starting after graduation. I was so excited that I didn’t ask what the salary was.

“Yes!” I shouted into the phone.

“Don’t you want to know how much we’re paying you?” he asked.

No! I wanted to scream, before I got hold of myself and answered with what I thought was studied nonchalance: “Sure.” I was too elated to pay attention to his answer.

At the Journal, my first front-page story as a full-time reporter wasn’t about high finance: it was a first-person account of being a street musician. To report it, I paired up with my childhood orchestra friend Michael to play Bach duets all over Manhattan. We earned the most in Times Square, from tourists on matinee day. We earned the least in front of the New York Stock Exchange, where the biggest contribution was five dollars from a bewildered investment banker I had once interviewed (“Joanne Lipman! What happened?!” he asked in alarm as he rushed by).

We averaged twenty-one dollars an hour in spare change from onlookers. The piece was headlined: “Our Violist Finds the Income Better than a Reporter’s.”

I sent a copy of my street-musician article to Raphael Hillyer at Yale, with a note thanking him. Our relationship had been strained ever since my bout of mono, which marked me as an insufficiently serious student. But he replied with a long, beautiful letter, saying that in writing the piece, “you became a professional musician.” I heard from Federal Reserve chairman Alan Greenspan, too, who later wrote wryly, “[Y]ou magically combined three subjects dear to me: the warmth of classical music performance, the kaleidoscope of humanity traveling the streets of the city, as well as the sheer joy of engaging firsthand in comparative wage analysis.” My parents had seen the article, of course, and cut it out to show their friends.

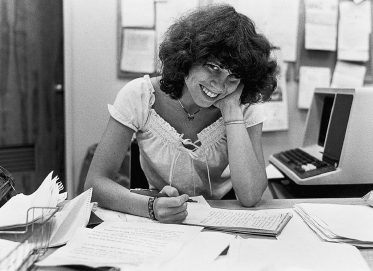

During a summer break from college, Joanne works the July 4 shift at her first newspaper job, as a copy girl/reporter for the New Brunswick, New Jersey, Home News.

But somehow in my excitement, something slipped my mind. Perhaps I was careless, or perhaps I thought it wouldn’t matter to him. Whatever the case, it didn’t occur to me to send the article or a note of thanks to Mr. K.

MELANIE

While I’m home on a school break, my dad helps me record audition tapes on the big reel-to-reel recorder in his studio. I send them out to every major symphony in the country. The first response comes quickly. I can’t wait to share the news with my boyfriend, Ed, a fellow conservatory student.

“Ed! They liked my tape! Chicago liked my tape!” I am thrilled. My first try, and I’ve already gotten a positive response, and from the legendary Chicago Symphony Orchestra, no less. This is going to be easier than I thought.

Chicago is one of the few major symphony orchestras that doesn’t require a preliminary tape. Anyone can show up to audition. But it’s expensive, flying all over the country. So if you can get a thumbs-up on a tape, it means you at least stand a chance in the live audition, where 250 players often show up for a single opening.

“Really? That’s great! Really? Wow! Really? When is the audition?” Ed is stunned. He knows lots of people who have taken auditions already. Often it takes years to land a job, or even to start making the finals.

“It’s in a month. And they sent out a new list of excerpts. I have to get one more piece to learn.” Symphonies generally require at least fifteen orchestral excerpts, most of which I have already been practicing.

“What piece?”

“A Strauss piece, Also Sprach Zarathustra. Is that hard? I’ve never heard it before.”

“Sure you have. Remember 2001: A Space Odyssey? ‘Open. The. Pod. Bay. Doors. Hal,’ ” Ed intones in a mechanical voice. “That’s the theme they used in the movie, it’s from that piece. I think it’s pretty hard.”

By the time I get hold of the music, I have run out of time. I brazenly fly to Chicago anyway, hoping the audition committee won’t ask to hear it. After all, they only allocate a few minutes to each person. I’ve learned everything else on the list. Maybe I will get lucky.

No names and no gender-specific pronouns are used when the proctor makes his announcement as I make my way onto the stage. I’m shielded by a tall white screen, so that the audition committee—nine members of the orchestra—can’t see me and I can’t see them.

“Candidate number sixty-three will play the Brahms concerto.”

For me, the concerto is the easy part, and I feel calm and focused. I play Brahms for about two minutes, then we move on to the excerpts. So far so good. The audition is going well. I can tell they like me because they keep asking to hear more.

“Strauss, please,” comes the disembodied voice from behind the white wooden screen.

My heart sinks. Damn! Now what do I do? There is no way to communicate directly with the committee. To ensure fairness and anonymity, this is how it’s done in the first round: no talking allowed, a carpet laid on the stage to mask the click of high-heeled shoes, a designated entrance for candidates so they will not accidentally run into the orchestra members.

The proctor places the music on the stand. I shake my head and lean toward him.

“I didn’t learn that one. It wasn’t on the first list!” I whisper urgently.

He looks at me, perplexed. I feel about three inches tall.

“Uh, the applicant did not learn this excerpt!” he announces loudly into the void.

Whispers, then, “Have the applicant play it anyway.”

Are they kidding? There’s no way I can sight-read this!

The proctor flips to the hardest section, a passage in a crazy key, so full of fast notes and markings that the page is more black than white.

I have no choice. It’s fight or flight. Okay, here goes. I go for it. I doubt I play one correct note. It sounds so bad it would be funny, if I hadn’t just blown my savings on an airline ticket.

“Try it again.”

Unbelievably, the committee is giving me another chance. Maybe they really like my playing? Maybe they can’t reconcile my painstakingly practiced and executed pieces with this god-awful mess? Maybe they’re having a laugh at my expense?

I play the passage again. It’s even worse than before.

“Thank you.”

There is a painful finality to their dismissal.

My first audition is over and so is my chance to play with the Chicago Symphony. I mentally kick myself. I recall the first time I blew an audition, years ago, when I sat crying on my dad’s lap. Don’t worry, Lastivko, he told me then. Pick yourself up and work harder next time. He’s right: I have learned my lesson. I will never be unprepared again.

I have a few hours to kill before my flight home. I go to a bar and get drunk by myself, then go shopping at Lord & Taylor, then stop to buy a Chicago pizza to bring back to Ed. When my plane lands, he’s waiting at the airport with a single red rose.

Steph and my dad still clash at times, one digging in more stubbornly than the other, but Steph’s passion for the violin is equally fierce. She wins a scholarship to West Virginia University, where my dad has already sent about half a dozen of his other students on music scholarships.

My dad and I drive her to school. In the dormitory, as we say good-bye, we linger. We know that this could be a final step, that Steph might drift away from us. But Steph surprises us both. Once she’s on her own, almost imperceptibly at first, the ground shifts. At West Virginia, my dad isn’t there for her to rebel against. Steph is finally free to be herself. She can “find herself,” in the words my father so loathes.

And the person she finds is… a lot like him.

Steph, like my dad, has a ferocious work ethic. She earns her music education degree while winning the university concerto competition. During the summers, she joins our dad to teach at his ASTA conference, coaching young string players and soaking up teaching tips. When she graduates, she is awarded a place in the same graduate performance program at the New England Conservatory that I have completed, studying with the same gifted teacher, Eric Rosenblith.

In Boston, we move into an apartment together. It is a tiny, roach-infested place on Westland Avenue, with a kitchen so small that my shirt once catches fire from the stove at my back while I stand at the sink washing dishes. I’m waiting for an audition break, hoping to get into a major symphony, while teaching and playing freelance gigs in Boston.

Steph’s love for music, like my dad’s, is full throttle. She has a lusty appreciation for it that is constantly reminding me of him. Writing to a friend about an advanced chamber music camp she gets into that summer, she describes her excitement:

They assigned me the Elgar Piano Quintet, 1st violin, and I had never heard of it… [I] found a recording of it & was shitting because it’s hard but so beautiful! I only have 1 week to learn this bitch part, plus 2nd fiddle Beethoven op18 #1 (the infamous “How do you like my feet?” quartet). That’s not too hard. But of course my recital stuff needs to be kicking ass also…

Meanwhile, I practice like crazy to try to win an orchestra job. I’ve read somewhere that playing an audition feels similar to running up six flights of stairs and standing on one leg on a rickety chair while trying to execute perfectly the most difficult passages in the violin literature. So while I practice, Steph makes noise, claps her hands, knocks into the furniture, flicks the lights, and whacks me with her purse, to see if I can keep playing no matter what. Anyone who passed by and looked in the window would have thought we were nuts.

After my first year of graduate school at the conservatory, I’m named a fellow with the Tanglewood Festival, an intensive orchestral training program in the Berkshire Mountains, where the Boston Symphony Orchestra is also in summer residence. There, early every morning, I run two miles and practice scales for an hour before the first orchestra rehearsal of the day begins at ten A.M., pausing only long enough to chug a glass of orange juice and pop a multivitamin.

All the students at Tanglewood—most of us conservatory upper-classmen or graduate students—want to get real jobs. We are all highly aware that during orchestra rehearsals, the Boston Symphony’s personnel director stands just offstage and watches us, ostentatiously taking notes on a clipboard. Harry Shapiro has the ultimate power to hire subs for the orchestra and for the Boston Pops Orchestra. Everybody wants to impress Harry. As we rehearse, the students all watch him watching us, adding another dimension to the already supercharged, competitive atmosphere. The students whisper that sometimes in the spring he holds first-come, first-served unofficial auditions, if you know the right day on which to call him.

My second summer as a Tanglewood fellow, I am named one of the concertmasters of the student orchestra. Coached by Boston Symphony and Juilliard String Quartet members, I get over some of my timidity. At a joint concert with the Boston Symphony, I sit in the front, between the symphony’s concertmaster and principal second violinist. Composer Aaron Copland, in one of his last public appearances, comes to hear us perform his Symphony No. 3; during the fourth movement, which starts with the “Fanfare for the Common Man,” I find myself weeping at its power and beauty and innocence. At an after-concert party at Miss Hall’s School, the swanky girls’ boarding school where students are housed, I muster all my courage and dance with Leonard Bernstein.

“Mr. Bernstein, playing with you has been the most amazing experience of my whole life,” I shout over the stereo thumping out the music of the Pointer Sisters.

The legendary composer of West Side Story twists his arms to the music, his head thrown back to the beat. “Your whole life is just beginning, my dear,” he shouts. “It’s all still ahead of you.”

Back in Boston, I get an unexpected phone call.

“Melanie. It’s Harry Shapiro.”

My brain freezes. I seem to have forgotten how to speak.

“Hello?”

“Um, yes. Sorry. Hi, Mr. Shapiro.”

“Melanie, we have some work for you.”

Mr. Shapiro needs an extra violinist, he says, to fill out the Boston Pops Esplanade Orchestra. The orchestra will spend several weeks in Boston, then tour the United States and Japan, conducted by composer John Williams.

“Let me give you the dates so you can check your schedule,” he is saying.

John Williams? Star Wars’ John Williams? Check my schedule? What, is he kidding?

The Boston Symphony Orchestra combines with the Tanglewood student orchestra for a concert. Conductor John Williams, the composer of film scores, including those for Star Wars and Schindler’s List, congratulates Melanie. Also pictured, from left to right, BSO concertmaster Malcolm Lowe, violinist Craig Reiss, principal second violinist Marylou Speaker Churchill, and violinist Rachel Goldstein, far right.

“Yes!” I say.

“The season starts in early June and runs through August.”

Damn. Early June?

“Um, is it possible to miss just one weekend? I have something planned for June twentieth.”

“No, it’s not. I’m sorry. It’s the whole summer, all or nothing.”

I only hesitate for an instant.

“Yes! I’ll do it!”

Now I just need to tell Ed that we’ll have to reschedule our wedding.

The life of a musician is a series of auditions. After touring with the Boston Pops and exhausting my savings flying around the country to audition for other big-city orchestras, I land a one-year contract with the Pittsburgh Symphony Orchestra. Ed and I, newly married after our hastily rescheduled wedding, pack up the battered Toyota Tercel that looks like a toaster oven on wheels and move to Pittsburgh.

Our wedding had been a cheerfully no-frills gathering at a local restaurant that we paid for ourselves. My ever-practical father had offered me a choice: he would buy me a violin or pay for the wedding. I didn’t have to think twice. My mother came, and Steph pulled out her violin to serenade us with Bach’s Air from Orchestral Suite No. 3. Baba scowled through the ceremony and boycotted the reception, furious that I didn’t get married in her Ukrainian church. My great-aunt Titka mocked my dress and makeup, then announced that her wedding gift was to buy a new dishwasher for my father. It didn’t matter. Ed just laughed and said that anything nice anyone did for my father meant more to him than any gift to us ever could.

That spring, the Pittsburgh Symphony, under conductor Lorin Maazel, is to perform in New York City at Lincoln Center’s Avery Fisher Hall, one of the great concert halls in America. It’s a thrill to be playing there on tour with a major orchestra for the very first time. Before the concert, we file onstage to warm up.

“What’s that?” my stand partner says, squinting into the crowd.

He’s pointing to the balcony. I look up from the music for Strauss’s Don Quixote, which we will be performing in a few minutes. Leaning over the edge of the balcony railing, a man is frantically waving a large white handkerchief.

“Look at that guy!” my stand partner laughs.

Stephanie plays Bach’s Air from Orchestral Suite No. 3 at Melanie and Ed’s wedding in 1987. The piece, one of Stephanie’s favorites, would be played at a much more somber occasion more than a decade later.

The handkerchief waver is flapping so energetically and leaning so far forward he looks like he might fall right off and plunge into the expensive seats below.

I take a closer look.

It’s my dad.

There he stands, pressed up against the balcony railing, his handkerchief unfurled. He is waving that thing like crazy, putting his whole body into the effort. He looks like a mahnyiak, as he might say. I’m overcome with the urge to either jump up and wave back to him or dive under my chair in embarrassment.

Instead, I wave my bow surreptitiously a bit in acknowledgment, trying to suppress a smile. My dad sits back in his seat, content that I know he is there. Across the darkened space of Avery Fisher Hall, I can see his face, lighting up his spot on the balcony just as sure as if he were plugged into an electric socket. He’s pointing me out to everyone in the seats around him.

“Mel, it’s unbelievable! People are leaving notes under my windshield wipers in the grocery store parking lot: ‘Do you have room for one more student?’ ”

After Steph earned her graduate degree, she took a position teaching violin on Martha’s Vineyard, the Massachusetts vacation haven seven miles out at sea. During our frequent phone calls, Steph gives me vivid updates about her new life. “I had to order more violins from the mainland, it’s been crazy!” she says. “Everyone wants to play. I’m not sure how I’m going to handle them all by myself.”

Steph has developed into an accomplished violinist. But like my dad, she has discovered her true passion is for teaching. Years earlier, he had told a newspaper reporter, “I believe teaching is a profession all its own. It’s no place for a frustrated maestro.” Teaching, for him, isn’t a fallback position. It’s a calling. And Steph has heard the call, too.

As a teacher, Steph is as gentle and soft-spoken as my father is loud and intimidating. But her approach to the fundamentals is the same. Like him, she assigns her students “Twinkle, Twinkle, Little Star” and “Lightly Row,” but then she mixes in her own transcriptions of Madonna and Bruce Springsteen songs. She rewards her students with stickers, stars, fuzzy-bear pencil toppers, and cookies and milk. Sometimes she allows them to play with one of her pet birds perched on their shoulders.

As well suited as she is to teaching, though, Steph is ill suited to the isolation of island living. After the seasonal crowds leave, she finds herself alone, living in a house at the end of a long dirt road. Life outside of work is dreary.

Stephanie teaches multitudes; here, with her Suzuki class on Martha’s Vineyard in 1990.

During the long winter evenings, Steph turns to her violin for company, preparing a full-length recital program that she schedules for the end of the school year that June. My dad, Ed, and I all come for the occasion. For old time’s sake, Steph and I perform our childhood favorite, Bach’s Concerto for Two Violins. Ed, succumbing to Steph’s entreaties, drags a vibraphone all the way out to the island on the ferry so he can perform a few jazz tunes for the crowd. My dad beams in the audience. He has presided over more concerts than he can count, but he is never more proud than of this one.

It is a fitting finale to her time on the island, since Steph has decided it’s time to move on. The next year she takes a new job, to teach violin in a burgeoning suburb—a town named in one survey as among the ten safest in the country—outside of Rochester, New York, called Greece.

That December, between Pittsburgh Symphony rehearsals, I fly to yet another orchestra audition. I am the last person to play that day, number 23 out of more than 250 applicants, and the committee is tired. Luckily, I don’t know that at the time. Downstairs in the fluorescent-lit basement hallway, after the votes are counted, the personnel manager gives me the good news. I am a finalist for the Chicago Symphony Orchestra.

Coincidentally, my father is also in Chicago for a music convention. I run down Michigan Avenue from Orchestra Hall as fast as I can in high heels, with a violin strapped to my back. The hotel elevator ride takes forever, and when my father opens his door, I fall into his arms, laughing and then dancing around the room.

“I did it! I did it! I made the finals!”

“Really? Wow,” my father says, unable to find the words. “WOW.”

“You’re my good luck charm. You should be in town for all my auditions!”

“So now what? What’s next? When are the finals?”

“In April. I have to come back then.”

“April? That weel give you four more months to practice. Lots of time—you can really prepare.”

“Don’t you worry, I am going to be prepared.”

For the next four months back in Pittsburgh I do nothing but sleep, eat, work, and practice. No fun allowed. I set a goal of practicing eight hours on a free day. If I have one rehearsal I can do six hours, and if I have a rehearsal and a concert I can do four. No days off, of course, but that’s nothing new; my dad has prepared me for this since I was little. My fingers bleed, and my neighbors call the police, but nothing is going to get in my way.

I am playing the best I ever have, but there is more to it than that. In my brain, something has clicked. In the old days, when I used to go to auditions, I would walk into the group warm-up room, looking around in awe at the great players surrounding me. I would find a corner and practice frantically until the last possible second before my number was called, fighting the irrational fear that I might somehow forget how to play the violin during the time it took to walk from the warm-up room to the stage.

Along the way, though, I realized something. There is a missing piece to the puzzle, and it doesn’t involve more practicing. My dad once told a newspaper reporter about student auditions: “Even though they might be strenuous, it’s part of growing up. And we work to prepare the kids, both musically and psychologically.” Now, finally, the psychological piece clicks into place. Before an audition, instead of exhausting myself in the warm-up room, I begin playing just a little to loosen up. Then I take out my knitting. While everyone around me is practicing the hardest parts over and over again, just like I used to do, I instead sit calmly knitting, centering my thoughts, focusing, relaxing.

The first few times it is difficult to break the pattern, to believe that it is more than just the sheer quantity of hours, the number of miles logged on the bow, that is going to win me a job. But I realize there is something else, something far more elusive. It’s not in my fingers, it’s in my head.

When I figure that out, everything else falls into place. And in April, Sir Georg Solti offers me a position as a violinist with the famed Chicago Symphony Orchestra.