Oh the moon shines bright

On Charlie Chaplin,

His boots are crackin’,

For want of blackin’.

And his baggy trousers,

They want mendin’,

Before they send him

To the Dardenelles.

BY THE SPRING OF 1915, AS THE GREAT WAR ERUPTED in its first bloody year, endless columns of khaki-clad Aussies, Tommies, and Kiwis streamed along the docks and swept up the gangplanks of the huge Egypt-bound cruise ships and converted luxury liners that were waiting to transport them to the port of Alexandria. There, on the city’s outskirts, they would bivouac in hastily erected tent cities while awaiting their final orders. To help keep step, set a lively marching pace, and lend a defiantly holiday mood of vagabond adventure at the outset of what, for many, would be a grim rendezvous with death on the crescent-shaped sands of Gallipoli, they sang that extemporized song whose words evoked the image of their informally adopted regimental mascot.

Back in London, during that 1915 spring, on the streets of Kennington and elsewhere, young children — the boys and girls who had just bid farewell to their fathers, uncles, brothers, friends, cousins, and neighbors as they marched off to the bloody Balkans — played on the pavements, chanting:

One, two, three, four,

Charlie Chaplin went to war.

He taught the nurses how to dance,

And this is what he taught them:

Heel, toe, over we go,

Heel, toe, over we go,

Salute to the King

And bow to the Queen

And turn your back on the Kaiserin.

And when America later changed its tune from “I Didn’t Raise My Boy to Be a Soldier” to “Over There,” boys and girls on the sidewalks of New York would turn to that street game in which bluff Charlie-boy soldiers showed brave Army nurses how to waddle off to war as they too sought the healing comic solace of play to master the pain and grief of saying goodbye to close friends and family they might never see again.

The strong emotional identification that the children of Kennington and those Balkans-bound foot soldiers formed with Chaplin’s early screen hero, the unsteady, flat-footed Little Tramp, was deeply rooted in the ordeals that each group was facing. But it also makes sense, from a broader sociological perspective, to think of their preoccupation with Charlie Chaplin as one reflection of a fashionable craze that was taking the Western world by storm in 1915. In New York, a chorus line of beautiful, tramp-costumed Ziegfeld girls with crepe moustaches pasted on their upper lips were delighting customers nightly with their rendition of “Those Charlie Chaplin Feet”; in Paris everybody who was anybody was learning to dance Le Charlot One-Step.

By 1915, a world already crazed by war was also in the process of finding escape in motion pictures. And after fifteen brief months and forty-one films, the new comedian was all the rage. Everywhere you went, Charlie was there to greet you: there were Chaplin dolls, toys, cartoons, games, comic strips, and books. Chaplin himself remarked that he couldn’t even purchase a tube of toothpaste at his local drugstore without encountering the unblinking gaze of his own likeness, in one commercial incarnation or another, staring back at him over the counter.

In the small cities and towns of Middle America, freckle-faced boys — those compulsive collectors of slingshots, squirt rings, and other magical paraphernalia aimed at warding off that age group’s sense of vulnerability — mailed off their nickels and dimes for Charlie Chaplin good-luck charms and magic horseshoes just like the one Charlie stuffed in his glove when he kayoed Spike Dugan in The Champion. An exemplar of brains over brawn, puny but sly underdog Charlie could outwit menacing hulks twice his size, which made him just the sort of trickster hero the youngsters admired. Undoubtedly their maiden aunts and bachelor uncles, when invited to Sunday dinner, groaned at the prospect of politely enduring yet another postprandial impersonation by their fully costumed nephews, who were all rehearsing for the Charlie Chaplin look-alike contests at the local nickelodeon.

For those in the motion-picture audience whose insecurities and chief preoccupations ran more toward members of the opposite sex, Charlie’s cute but libidinally outrageous screen image permitted both psychological identification and imitation in the service of courtship or dalliance. Sallying forth cockily in their Charlie Chaplin getups to fraternity house costume parties and masked society balls, swains of all ages and shapes approached maidens of their choice — sometimes with romantically bashful but persistent fortitude, other times with aggressive mock-licentiousness bordering on good-natured but incorrigible lechery. If romance failed, they could shrug their shoulders with philosophical resignation, gracefully back-kick a cigarette butt, and shuffle down life’s highway without looking back — as Charlie had just done in The Tramp, his first picture with an unhappy ending. If love succeeded but the pair did not happen to win the plaster-of-Paris statuette of Charlie being awarded as first prize at the next week’s local dance contest, no matter — the statues too were for sale.

Advertisements in Photoplay magazine announced that pinning a dollar bill to the coupon and mailing it off to Chicago would command a figurine of the most famous clown in the world. They were selling like hotcakes. As public opinion polls throughout the world soon revealed, in some remote corners of the globe the Little Tramp’s graven image was becoming as well known as Jesus Christ’s, or better.1

The popularity of “The Moon Shines Bright on Charlie Chaplin” spread swiftly from the Dardanelles to the Hindenburg Line, where foot-slogging, battle-weary veterans of the European campaign, trudging through the mud and huddling in the trenches, found themselves conjuring, to the tune of “Red Wing,” sweet memories of sitting as civilians in the peaceful Saturday afternoon darkness of their local nickelodeons and Bijoux while images of Charlie Chaplin’s familiar baggy-trousered, flat-footed, scrappy Little Fellow flickered on the silver screen.

Behind the lines, in military hospitals, special vertical movie projectors were being rigged to allow Chaplin’s morale-boosting Little Fellow to leap to life and waddle on the ceilings of surgical and medical wards for those too weak or wounded to sit up in bed. There were even physicians’ case reports of the Little Tramp’s humorous screen image speeding the recuperation process of individual patients; sensation-hungry tabloid journalists took to referring to them as Chaplin’s miracle cures. No less thoughtful a writer than Alexander Woollcott would conclude that “such a bearer of healing laughter… the world had never known.”2

Almost from the start of his movie career, Chaplin appreciated that his screen character’s instant popularity and universal appeal stemmed in large measure from his apparent ability to alleviate misery:

In a world where so many people are troubled and unhappy, where women lead such dreary lives as my mother did when I was a boy, where men spend their days in hard unwilling toil and children starve as I starved in the London slums, laughter is precious. People want to laugh; they long to forget themselves for half an hour in the hearty joy of it. Every night on a hundred thousand motion-picture screens my floppy shoes and tricky cane and eloquent mustache were making people laugh, and they remembered them and came to laugh again. Suddenly, almost overnight, Charlie Chaplin became a fad, a craze.3

But after the initial thrill of overnight celebrity wore off, Chaplin would grow more circumspect and ambivalent as he came to realize that being the object of a fashionable craze posed the hazard of pursuit by admirers who behaved in a crazed fashion.

During the years that followed, there would be times when Chaplin’s reaction to his screen character’s enormous popularity and the resultant idolatry lavished on his actual person by vast crowds was tinged with distaste (and concern for his personal safety). On one such occasion, a return visit to London in 1921, after being mobbed by throngs of well-wishers including many thousands from his native slums, he confided to a friend, Thomas Burke:

Oh, God, Tommy, isn’t it pathetic — isn’t it awful? That these poor people should hang round me and shout “God bless you, Charlie,” and want to touch my overcoat, and laugh, and even shed tears — I’ve seen ’em do it — if they can touch my hand. And why? Why? Because I made ’em laugh. Because I cheered ’em up. Cheered ’em up! Ugh! Say, Tommy, what kind of filthy world is this — that makes people lead such wretched lives that if anybody makes ’em laugh they want to kiss his overcoat, as though he were Jesus Christ raising ’em from the dead? Eh? There’s a comment on life.4

Having managed to escape poverty and misery by creating the Little Tramp, Chaplin could find such encounters with members of his former social class disquieting. But it was not the pathos he perceived behind the crowd’s collective identification with both his fictional character and the meteoric success story of his actual life that he found most upsetting.

If an archetype is, in a Jungian sense, an image or icon powerful enough to stir dormant communal emotions and, by doing so, unleash primordial group behavior, there were moments when the public’s reaction to Charlie Chaplin the screen character and Charlie Chaplin the film star could be said to resemble that primitive behavior. Those mobs of fans with outstretched arms could be transformed, through their collective admiration — and equally passionate, unconscious envy — into hordes of souvenir-hunting scavengers swept up in a feeding frenzy.

On one occasion (the New York premier of a friend’s movie) clothes were literally torn from Chaplin’s back by admirers who, in their hunger for some memento of the rags-to-riches story of their movie star hero, seemed determined to return elegantly dressed Charlie to the abject and tattered aboriginal state of his Little Tramp:

The tide changed. I was swept back towards the entrance of the theatre.… My hat flew towards the heavens. It has never returned to me. I felt a draught. I heard machinery. A woman with a pair of scissors was snipping a piece from the seat of my trousers. Another grabbed my tie and almost put an end to my suffering through strangulation. My collar was next. But they only got half of that. My shirt was pulled out.The buttons torn from my vest. My feet trampled on. My face scratched.… I kept insisting that I was Charlie Chaplin and that I belonged inside.… Insistence won. As though on a prearranged signal I felt myself lifted from my feet, my body inverted until my head pointed towards the center of the lobby and my feet pointed towards an electric sign advertising the Ziegfeld Roof. Then there was a surge and I moved over the heads of the crowd through the lobby.5

And inside those dream emporiums, image-hungry movie audiences suspended their disbelief and gorged themselves weekly, or even more frequently, on their favorite comedian, until the Little Tramp’s essence was digested and assimilated into their own lives and daily routines and he felt as much a part of them as friends or family. So why not reach out and touch the actor who played Charlie Chaplin? What if he was pummeled and his clothes torn in the process? After all, their celluloid hero was an immortal slapstick god, invulnerable to the cuffs and blows and kicks of fate, fortune, and neighborhood policemen.

As children the world over have always known, clowns can be crushed, mangled, or strangled but never killed. No matter how dire Charlie’s predicament at the end of one Keystone farce after another — being knocked unconscious (Tango Tangles), dynamited (Dough and Dynamite), clubbed over the head repeatedly with a cop’s nightstick (His Prehistoric Past), “liquidated” by mock drowning on a sinking ship (The Rounders), or collapsing into an apparently fatal drunken stupor (Face on the Barroom Floor) — he could always be relied upon to resurrect himself by the following Saturday afternoon. The life-size cardboard image of the Little Tramp would be hauled again out of the box office and placed on the sidewalk in front of the neighborhood movie theater, announcing—like some miraculous second coming —the arrival of his latest and greatest celluloid incarnation with the sign caption “I am here to-day!” Singing in praise of their film god’s comedy, children of privilege and slum urchins alike would eventually warble (to the tune of “Gentle Jesus”):

Charlie Chaplin, meek and mild,

Took a sausage from a child.

When the child began to cry,

Charlie slapped him in the eye.

A screen character whose transcendent appeal would still be compelling a full century after the birth of his creator, the Little Tramp had barely completed the first leg of his journey toward fame and fortune by the time those soldiers marched off to meet their fate on the shores of Gallipoli. Unlike the forgotten men who once sang his song, the Tramp’s odyssey would eventually bring him to the ranks of Falstaff, Don Quixote, and a handful of other comic immortals who, ironically, the world remembers largely for their mock valor.

But on the rainy February afternoon of the Little Fellow’s birth back in 1914, all of those developments lay in the future. That day the scrawny newcomer to the Keystone Film Company rummaged through the wardrobe department in the bungalow that served as the male actors’ dressing room, borrowed a pair of Fatty Arbuckle’s billowing pantaloons, trimmed down mountainous Mack Swain’s prop moustache, slipped his delicate feminine feet into Ford Sterling’s size-fourteen gunboats, and soon waddled onto the streets of Venice, California, where a children’s soap box derby was in progress.

As the signs posted on the big red Pacific Electric trolleys that rattled and bumped their way across the Los Angeles city limits into the remote backcountry wilderness of Southern California reminded the passengers, shooting jackrabbits from the rear platform of the cars was strictly forbidden. It took three consecutive days of anxiously commuting back and forth on the Tropico Line, which ran all the way from his hotel to far-off, exotically tropical Glendale, before Chaplin finally gathered the resolve to physically enter Keystone Studio headquarters. The studio occupied an old farm in the formerly sleepy but now bustling trolley stop of Edendale. Edendale’s wooden storefronts, quaint shacks, and lumberyards looked sufficiently frontierlike that the studio’s previous occupant, Thomas Ince, had encountered no difficulty in producing a convincing series of cowboy one-reelers there before moving his home on the range to Santa Monica.

Each of the two preceding days Charlie had ventured no farther than the ramshackle green fence that demarcated the boundaries of the Keystone lot. He had lingered for half an hour at the “safe distance” of a street corner located directly across from the studio’s Alessandro Street entrance, and then, unable to muster “the courage to go in,”6 retreated from that alien environment to his digs at the Great Northern Hotel in downtown L.A., just a short walk from the old Empress Theatre where he had played so often with Alf and the rest of the Karno bunch. Filled with such “qualms about leaving the troupe in Kansas City”7 a week earlier that he had wept in private after the final curtain on closing night, Charlie was still beset by misgivings as he wavered at the gates of Keystone and on the threshold of a radical change in career direction.

Chaplin’s reservations were not just about bidding farewell to the small band of friends and countrymen with whom he had worked and toured in a foreign land for three years. Nor was he merely insecure over lapsing from seasoned veteran and well-established headliner to untested new kid on the block, and foreigner to boot. The “little Englisher” or “limey” comedian was what the back-slapping he-man gang of Keystone regulars would soon call him.8 (Further, they would welcome the newcomer with their traditional practical joke, which consisted of electrically wiring the john seat in the male actors’ dressing room with the studio’s Ford generator.)

Professionally speaking, Chaplin was moving from an established and respected mainstream branch of the theatrical profession to what was still looked down on as a disreputable, vulgar form of cheap mass entertainment. By the end of 1913, America’s burgeoning film industry was in fact beginning to emerge from its artistic infancy — a development in which Chaplin himself would be instrumental — but this was not a consideration in which the twenty-four-year-old music hall star could take comfort as he vacillated at the gates that December. Despite the indisputable logic of doubling his salary overnight, Chaplin retained traces of a popular prejudice still held by middle-class theatergoers and many actors as well: that abandoning an established stage career for the movies was professional suicide. As one film historian put it:

There was good reason why the movies were held in contempt by polite society. The nickelodeons weren’t quaint prototypes of the present-day neighborhood theatre, as they are often remembered. They were smelly, urine-stinking, unsanitary firetraps, tucked away in tenement districts, patronized only by immigrants and the poor, sometimes by prostitutes and pickpockets and other denizens of the dark. Nice people didn’t go to nickelodeons, or if they did, they wore big hats and looked over their shoulders before entering. The stage community looked down on the movies.… the average movie ran ten minutes or less, enough time to sketch in a brief dramatic anecdote, but not long enough for any detailed plot or character development. Film acting wasn’t real acting — it was making faces and funny gestures in front of a blackbox that added ten pounds to your waist and ten years to your face.9

As ambivalent about catering to the coarse appetites of nickel customers as he had once felt about pandering to the unsophisticated two-penny tastes of working-class stiffs in the music halls where he had been forced to play after leaving the Duke of York’s, Chaplin was “not terribly enthusiastic about the Keystone type of comedy,” which in his professional opinion was little more than “a crude mélange of rough-and-tumble.” Still, having seen examples of Keystone’s already famous productions before signing his contract — they were, as he mentioned in his letter to Syd, considered the best comedy films being made in the industry at that time — Charlie reassured himself: “A year at that racket and I could return to vaudeville an international star.”10 Undoubtedly it was a comforting rationalization to ponder as the Tropico trolley rumbled past exotically tropical palm, eucalyptus, acacia, pepper, and night-blooming jasmine on its way again to the Edendale studio.

Chaplin’s first glimpse of Keystone occurred at the studio entrance at noon, just as a steady stream of carpenters and cameramen, errand boys and extras, costumed actors and actresses, including the Keystone Kops themselves, poured noisily onto Alessandro Street in search of their midday meals at the general store across the way. Desserts could be purchased at Greenburg’s Bakery down the street, which, apart from feeding the hungry actors, did a thriving business supplying the studio with a never-ending stream of inedible prop “custard” pies (actually made of a paste that registered better on film) for Keystone’s most famous trademark gag — a pie in the kisser. The incredible ambidextrous ease with which he could simultaneously splatter two opponents with pies in the puss as they charged him from opposite directions would soon earn Fatty Arbuckle recognition as Keystone’s most valuable pastry thrower.

It was through that same studio gate that Keystone’s other hallmark gag —the comic chase — periodically erupted in the form of wild pursuits by the Keystone Kops. Spilling out onto local streets and highways that had been made slick with a mixture of soapsuds and motor oil, a dazzling procession of paddy wagons, motorcycles, bicycles, baby buggies, tin lizzies, and flivvers slipped, slithered, and careened into one another, mowing down pedestrian stuntmen, knocking over water-spewing prop fire hydrants, and strewing comic policemen in the wake of their expertly choreographed near misses with Pacific Electric trolleys and speeding locomotives. (The breathtaking accuracy was a camera trick accomplished by shooting near collisions in reverse action and projecting the film backward to create the illusion of forward motion.)

As one might expect, public opinion among the citizens of Edendale was divided over the good-natured chaos and mayhem emanating from the fun factory in their midst. Keystone was clearly good for business, but the town’s founding fathers were a stern band of God-fearing, Bible-toting ex-farmers from the Midwest who had selected the name Edendale as a scriptural tribute for the garden paradise that had been their sleepy hamlet and many of them were less than sanguine over the prospect of having the town overrun by “movies” — a nickname applied to those blasphemous East Coast actors themselves.

While that raucous lunchtime gang of “movies” spilling out of the studio was already enough to stimulate Chaplin’s worst fears of crude assembly-line practices within, his first glimpse of its inner sanctum intensified his anxiety. On his third try — “dragging myself by the collar”11— Charlie forced himself through the gates, and into a sleepy bungalow whose rustic facade belied the madness of the mass-production operation going on just beyond:

A glare of light and heat burst upon me. The stage, a yellow board floor covering at least two blocks, lay in a blaze of sunlight, intensified by dozens of white canvas reflectors stretched overhead. On it was a wilderness of “sets” — drawing-rooms, prison interiors, laundries, balconies, staircases, caves, fire-escapes, kitchens, cellars. Hundreds of actors were strolling about in costume; carpenters were hammering away at new sets; five companies were playing before five clicking cameras. There was a roar of confused sound — screams, laughs, an explosion, shouted commands, pounding, whistling, the bark of a dog. The air was thick with the smell of new lumber in the sun, flash-light powder, cigarette smoke.12

There, on that infinitely adaptable open-air stage, in the intense glare of a hot Southern California sun whose ovenlike radiance was magnified, reflected, and diffused in order to ensure that figures in dizzying motion would register crisply on the low-emulsion film of the day, at an average rate of two to three per week, some 140 movies of exceedingly variable artistic quality had already been ground out in the course of the year just ending, 1913.

But the demands of the moviegoing public for Keystone’s product were so insatiable, and the box-office rewards so compelling, that the expenditure of time and effort required to produce motion pictures with higher technical values (finer photography, better shot matching, tighter editing) or more thoughtful construction (character development, plot continuity) was not something the director of the Edendale studio was likely to consider seriously. A shanty Irish former construction worker who had been employed at the American Iron Works in East Berlin, Connecticut, before making his show business debut in New York City’s tenderloin district playing the hind end of a horse on the burlesque stage, Michael Sinnott, aka Mack Sennett, was supremely confident that his own working-class tastes faithfully reflected what America’s working-class audiences wanted to see. According to Keystone’s leading comedienne (and Mack’s sometime girlfriend), a sassy Staten Island girl by the name of Mabel Normand, the big lug’s crude sensibilities made her think of “a flatfoot store detective”13 when they had first met back East five years earlier at the old Biograph Studio.

Anxious to impress that pretty, dark-eyed, sixteen-year-old artist’s model with the sexy gams, twenty-eight-year-old Mack had boasted to Mabel of his plans to start a comedy studio of his own, hinting that there might be a place for her in those operations. And with characteristic Sennett braggadocio, Mack announced that he was preparing for his life’s goal by learning all there was to know about moviemaking from his good friend D. W. Griffith. While any claim of a deep personal intimacy or shared artistic vision with that lanky, hawk-beaked, aristocratically aloof Southerner was pure blarney on Mack’s part — Griffith would use adjectives like “burly,” “good-natured,” and “bear-like” in the characteristic detachment with which he later remembered Sennett as a character actor who had reminded him of someone’s “idiot brother,”14 a low comedy role in which D.W. typecast him on several occasions — it was also true that, appearances aside, Mack was no dummy. Quick to recognize Griffith’s as yet undiscovered genius, that crude but highly intelligent Son of St. Anthony made up his mind to pump the reserved and humorless Son of the Confederacy for as much cinematic wisdom as he could get.

On discovering that Griffith loved to unwind at the end of his sixteen-hour workdays by walking from Biograph’s East Fourteenth Street brownstone on Movie Exchange Row to his apartment on East Thirty-seventh Street, Mack developed a sudden yen for hiking:

When Griffith walked, I walked. I fell in, matched strides, and asked questions.

… We used to … wander the streets, and talk about the future of motion pictures.

“I want to put together full-length stories,” he would say. “Not merely little scenes such as we photograph now.…

“Writers do it. It’s done on the stage. Why not in movies?”

… I learned all I ever learned by standing around, watching people who knew how, by pumping Griffith, and thinking it over.

I would have pumped anybody. It was sheer good fortune that made it possible for me to pump a genius.15

Hannah Chaplin (stage name Lily Harley), circa 1885, at the height of her beauty The loss of her mental faculties in 1903 devastated fourteen-year-old Charlie. (Courtesy Jeffrey Vance Collection)

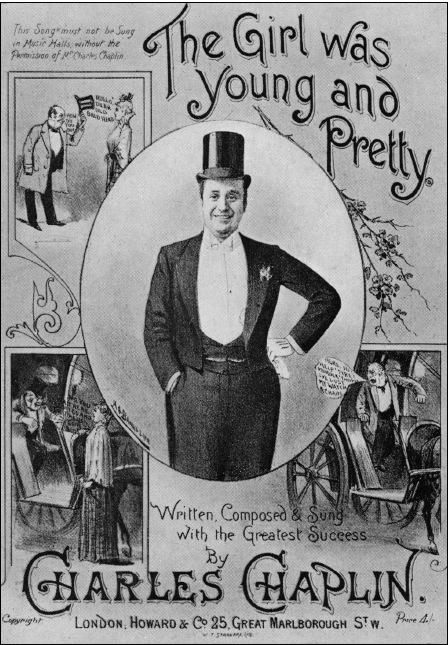

Charlie Chaplin Sr., 1885. His father’s premature death from severe alcoholism affected young Charlie profoundly. (Photograph by H. T. Reed, courtesy Jeffrey Vance Collection)

The Lion Comique, early 1890s. Chaplin Sr., a famous stage actor in his day, portrayed himself as an elegant man-about-town with a fondness for the bottle and the ladies. “I can’t remember a time when I wasn’t trying to follow in my father’s footsteps,” Chaplin said. (Courtesy Jeffrey Vance Collection)

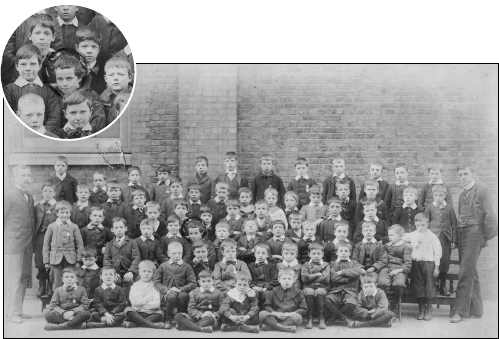

Center, circled, Chaplin at age seven, at the Central London Poor Law School at Hanwell, 1897. “My childhood ended at the age of seven,” Chaplin once told a reporter. (Courtesy Jeffrey Vance Collection)

Center, in bowler hat, Chaplin with Casey’s Court Circus Company, 1906. He was the star of the company. (Courtesy Jeffrey Vance Collection)

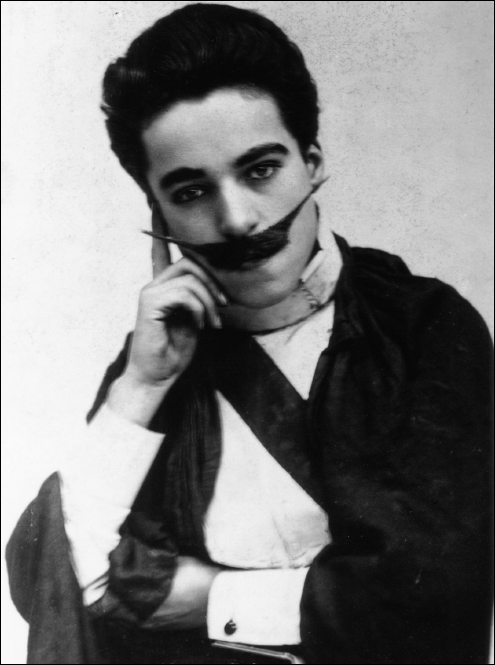

Young Chaplin impersonating Dr. Walford Bodie, a famous music hall medical charlatan who “cured” patients with electricity and hypnosis, 1906. This was one of Chaplin’s first solo comedy sketches in Casey’s Court Circus. (Courtesy Jeffrey Vance Collection)

Chaplin arrived in Los Angeles in late 1913 when Hollywood was still a dusty farm town and Beverly Hills little more than an undeveloped sagebrush wilderness full of jackrabbits and coyotes, an image he captured here in The Idle Class, 1921. (Courtesy Roy Export)

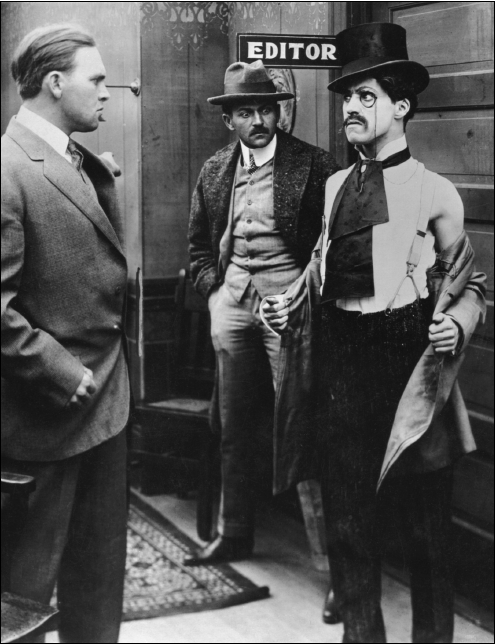

Chaplin in his first film, Making a Living, 1914, in which he plays an impecunious charmer. Chaplin’s character bears a striking resemblance to Ella Shields’s famous Burlington Bertie, who also sported a monocle and cane, pleaded an empty belly, and projected the false facade of a man of the world. (Courtesy Jeffrey Vance Collection)

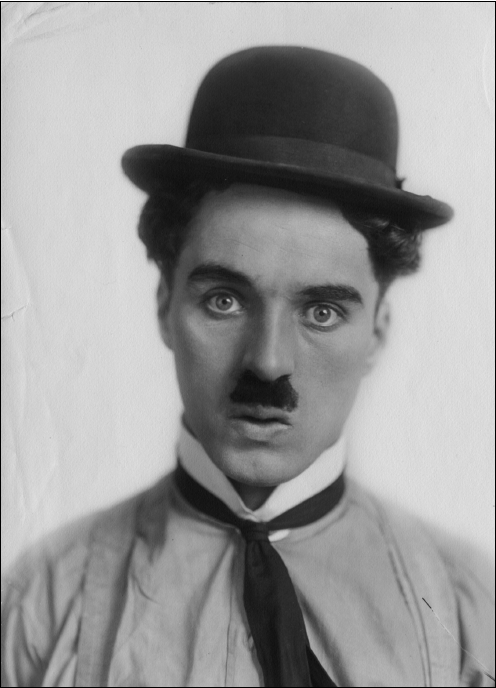

Chaplin, age twenty-six, circa 1915. Charlie Chaplin’s Own Story, narrated that year, was a cavalier concoction quite unlike My Autobiography a half-century later. (Courtesy Jeffrey Vance Collection)

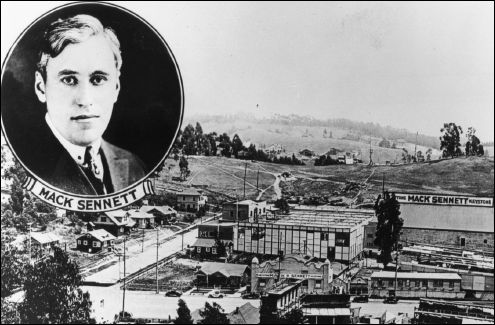

Mack Sennett and Keystone Studios in 1916. Chaplin made thirty-five shorts for Sennett during the first year of their working relationship, and the Little Tramp debuted in Chaplin’s second Sennett film, Kid Auto Races. (Courtesy Los Angeles Herald-Examiner and Los Angeles Public Library)

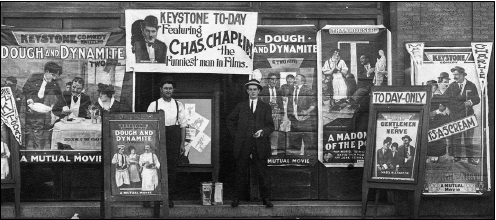

Sennett advertising for one of Chaplin’s shorts, Dough and Dynamite, 1914. (Courtesy Jeffrey Vance Collection)

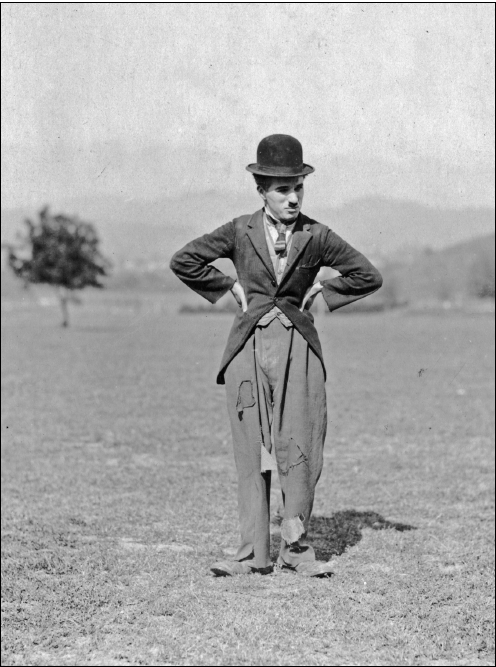

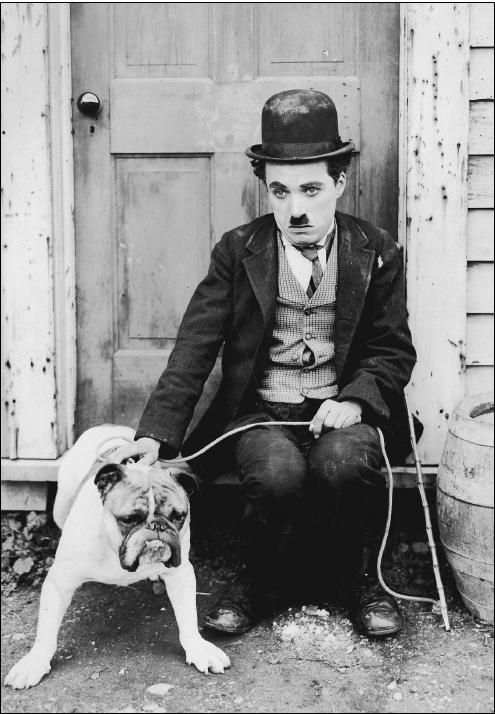

Birth of the Tramp, circa 1915. Chaplin’s evolving screen character parodied and memorialized his father, but he warned his fellow actors, “You’re liable to kill your enthusiasm if you delve too deeply into the psychology of the characters you are creating.” (Courtesy Jeffrey Vance Collection)

The Champion, 1915. Chaplin’s screen character developed gradually into a comic Everyman underdog. (Courtesy Jeffrey Vance Collection)

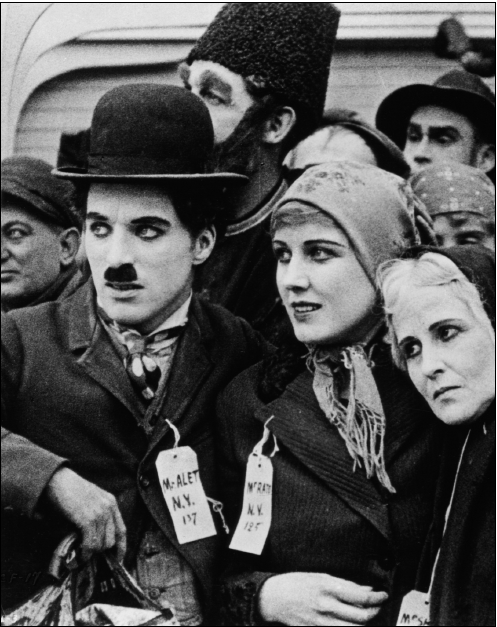

The Immigrant, 1917, Chaplin’s comic valentine to the America Dream. (Courtesy Jeffrey Vance Collection)

Brothers in arms, 1918. Charlie and Sydney Chaplin on the set of The Immigrant. After their mother’s hospitalization, Sydney became Charlie’s legal guardian when Charlie was only fourteen. A music hall star in his own right, Sydney helped Charlie get his first big break in show business and later put his career on hold to act as Charlie’s financial manager and advisor. “If Sydney had not returned to London, I might have become a thief.… I might have been buried in a pauper’s grave,” Chaplin confessed. (Courtesy Jeffrey Vance Collection)

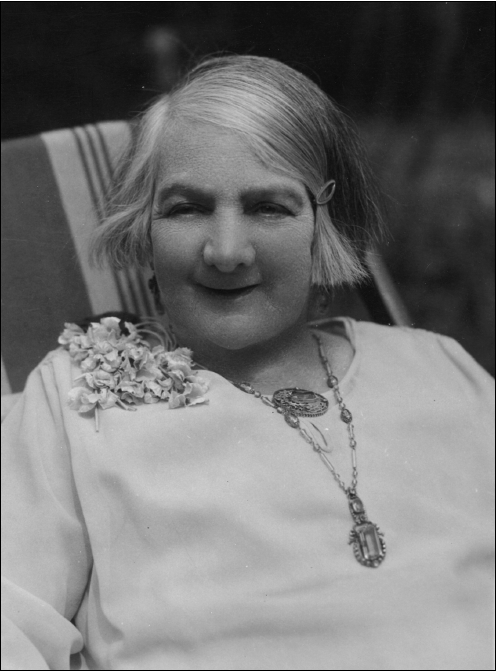

Hannah Chaplin, circa 1926. Though her beauty had been lost two decades before, she was now comfortable after a life marked by neurosyphilis, severe malnutrition, and chronic physical exhaustion. (Courtesy Roy Export)

Final scene from City Lights, 1931. The theme of rescuing and redeeming fallen women — stand-ins for his mother — runs throughout Chaplin’s films. Eminent film critic James Agee said this scene, in which Chaplin rescues a blind flower girl from poverty, was “enough to shrivel the heart to see,” and called it “the greatest piece of acting and the highest moment in movies.” (Courtesy Roy Export)

A Chaplin family Christmas card, 1964. Counterclockwise, from center: Oona O’Neill Chaplin, Charlie Chaplin, and their children Josephine, Victoria, Eugene, Jane, Annette, and Christopher. Absent from the photo are their two oldest children, Geraldine and Michael. (Courtesy Yves Debraine)

Although there was no way then he could have appreciated it, it was likewise Charlie Chaplin’s equally “sheer good fortune” not only to arrive at a critical point but to have the opportunity to “pump” the man who had just finishing pumping the man whose pioneering imagination, more than anyone else’s, was directly responsible for the revolutionary artistic, economic, social, and cultural changes about to take place in the movie industry.

Mack would later sum up his five-year association with Griffith as “my day school, my adult education program, my university.”16 And with a smart click of the heels and courtly bow, Erich von Stroheim would deliver his own estimate of such a priceless educational opportunity: “For you, Mr. Griffith, I would work for a ham sandwich a day.”17 While at Keystone — paying Chaplin double his Karno salary — Mack Sennett would distill what he had just learned from the master and provide a completely untutored Charlie Chaplin with a highly condensed, state-of-the-art, one-year crash course in all aspects of filmmaking.

“There’s another sausage,” Griffith is reputed to have remarked after one of his 450 films rolled off the assembly line during his six-year stint at Biograph from 1908 to 1913.18 Roughly 15 percent of that output was comedy, a fact generally overlooked in view of Griffith’s subsequent lack of interest in the genre. By March of 1911, D.W.’s indifference was sufficiently strong that he gladly turned over the directorial responsibility for almost all of Biograph’s slapsticks to a very eager Mack Sennett who, in addition to serving as Griffith’s faithful walking companion, had already written and/or directed a handful of immemorable half-reelers and acted in about fifty Griffith films, including some twenty-five comedies. (A second-rate, one-note comedian, Mack typically played the rube, hayseed, yokel, bumpkin, and, of course, dumb department-store gumshoe — the part he happened to be playing when Mabel first saw him.)

Griffith’s reluctant descent, from a creative inclination to zoom and soar gracefully in the ethers of the heroic, back to the requirements of earthbound, seat-of-the-pants low comedy, was an artistic compromise forced upon him by his new employer’s need to remain competitive with other filmmakers by furnishing America’s moviegoing public with programs containing a broad range of subjects, varying from serious drama, including old-fashioned melodrama, to cops-and-robbers adventure and cowboy-and-Indian westerns, as well as broad slapstick farces. Half-reelers ran some five hundred feet and lasted seven to ten minutes, with full-reelers and two-reelers of commensurate length. Theater programs were generally an hour long.

Arriving on the New York filmmaking scene near the end of 1907, at the height of the Nickelodeon Era, when many movies were little more than crudely assembled entertainments for the illiterate and the uneducated, projected on bedsheets tacked up on the rear walls of improvised storefront theaters in working-class neighborhoods and shown to the musical accompaniment of scratchy gramophones and tinkly secondhand pianos, D. W. Griffith had caught a train to the Bronx with his first film script in hand. Making an instinctive beeline for the one man, Edwin Porter, who had produced anything of notable artistic quality in American film up to that time (The Great Train Robbery, 1903), Griffith had been crestfallen to have his own first effort rejected by the Edison Studio.

Within a month, however, he had moved downtown to one of Edison’s major competitors, Biograph, where, in addition to acting and writing, he began to direct. The full name of his new employer was the American Mutoscope and Biograph Company, a reference to those old hand-cranked movie viewers, and the studio was also in the business of keeping America’s penny arcades well supplied with their product. Griffith’s bosses had made it clear that they expected him to tell stories in pictures with a simplicity that anyone coming in off the street would be capable of understanding.

Griffith had grown up in a family in which Shakespeare’s plays were read aloud; he had come to films from a failed career attempt as a dramatic actor on the legitimate stage. His literary tastes ran to Dickens (his favorite), Tolstoy, Poe, Browning, Twain, R. L. Stevenson, James Fenimore Cooper, and Jack London — to name but a few of the many writers whose lively tales he would adapt to the taste and the grasp of Biograph’s nickel-and-dime customers. In an incredibly feverish five-year period of trial and error, translating into film the narrational techniques of other people’s novels, short stories, plays, poems, and operas — in addition to the many tales he wrote himself — Griffith synthesized the basic storytelling grammar of cinema as we know it today.

The term “synthesized” is chosen advisedly, because as film historians are quick to point out, almost every narrative device Griffith employed had already been stumbled upon, if barely utilized, by filmmakers before him. Working without such modern aids as formal shooting scripts or storyboards, composing shots and sequences and entire tales from his head as he went along, Griffith refined the techniques of his colleagues and predecessors until at last his creativity could no longer be stimulated by the previously useful exercise of compressing entire epics into half-hour films. After seeking permission from Biograph to make his first feature film and being refused, Griffith went off on his own in 1913 — Sennett having left to start Keystone in August of the preceding year.

That “full-length” story Griffith most wanted to tell, and for which he is most remembered, was a legendary one that he later recollected having first overheard in bits and snatches during mealtime conversations when he was a small boy playing under the dinner table of his family’s rural Kentucky home. Griffith’s father, Colonel Jacob Griffith — also known as Thundering Jake and Roaring Jake for his powers of oratory — loved to spin “boozy yarns,”19 especially of his very real adventures as a Confederate cavalry officer who had been wounded on multiple occasions. Shiloh and Chickamauga were household words, and Sherman’s march to the sea loomed as large in the ten-year-old boy’s imagination as did the sudden death at that time of his father, “the one person I really loved the most in all my life.”20

Informed by their family physician that his father had died of peritonitis caused by the dehiscence of an old, poorly cicatrized war wound — allegedly sutured with inferior thread as a result of the Union’s punishing naval blockade on Southern shipping — the small boy coped as best he could with that “blow out of the past,”21 whose bitter memory he tucked away alongside his daddy’s treasured tales.

Some thirty years later, having finally earned the artistic freedom to give full rein to his passions and his cinematic imagination, Griffith would select a novel, Thomas Dixon’s The Clansman, in which he would unconsciously embed those memories of his father to create a monumental historical evocation of the War Between the States. As the title of that book implied, Griffith’s incredibly powerful film — in the outraged eyes of black leaders and liberal intellectuals alike — was rabidly pro-Southern and poi-sonously racist in its attitudes. Truly astonished and hurt by the vehemence with which that small but vocal minority denounced him for reopening a nation’s wounds — to the point of demonstrating and picketing as well as raising the fear of race riots and circulating “crazy talk of dynamite”22 — a by then unstoppable Griffith would respond by making his very next film a passionate indictment of other people’s intolerance, of course including the moral hypocrisy of supposedly liberal do-gooders and social reformers.

But message aside, Griffith’s groundbreaking Birth of a Nation would be hailed as an infant industry’s first great work of art and honored with the first screening of a motion picture in the White House, in February 1915—just as those Dardanelles-bound convoys set sail for the port of Alexandria. Not only would Griffith’s opus serve as a magnet to draw respectable middle-class audiences into America’s movie theaters, broadening forever the economic and social base of film by demonstrating conclusively that for as many as forty-eight consecutive weeks, in clean, handsomely appointed theaters located in good neighborhoods, respectable, well-educated people were willing to part with as much as two dollars of their hard-earned money for reserved prime-time seats to witness what they considered, for the first time, a cultural event on a par with the legitimate stage. As Woodrow Wilson put it, “It is like writing history with Lightning.”23

But back in early 1914, while D. W. Griffith labored feverishly to create his brainchild out of the legacy of his childhood, an equally industrious Charlie Chaplin — who had just begun to learn the ropes by working as a comedian for the empire-building, crude ape of a man who had only recently finished picking up the tricks of the trade from D.W. himself — was about to dip into his own paternal legacy and invent that screen character whose image would, almost overnight, become legendary.