Nothing (not even God) now disappears by coming to an end, by dying. Instead, things disappear . . . as a result of their transfer into the secondary existence of simulation. Rather than a mortal mode of disappearance, then, a fractal mode of dispersal.

(Baudrillard 1993a: 4)

It is forbidden to unplug yourself, and not only in active, interactive social life, but also on your deathbed: it is forbidden to tear out the tubes, even if you want to . . . The network principle carries with it the absolute moral obligation to remain plugged in.

(Baudrillard 1990: 197)

Jean Baudrillard (1929–2007), a French thinker associated with the Events of May 1968 who subsequently staged his own disappearance from the rarefied world of academia in order to reappear as a free radical, an agent provocateur of the cultural sphere, understood the nature of disappearance better than most – and, with it, the fate of the world. His position outside the academy allowed him to bear witness to the events, non-events, and processes of disappearance that are documented in the series of interviews – employing that term sensu amplo – brought together in this volume. What we shall continue to refer to as ‘interviews’ as a convenient short-hand in fact encompasses a far wider range of dialogical formats: panel discussions, round tables, and question-and-answer sessions, as well as interviews as conventionally understood.

Baudrillard’s withdrawal from the French academic scene, whilst hardly a deliberate ploy, nonetheless marked his destiny. It allowed him to disengage from the established currents of academic thought, to escape the gravitational pull of notions such as alienation, class struggle, cultural capital, the unconscious, desire, and so on, and to embark on an ex-orbital trajectory that allowed his own singular perspective to emerge. This perspective ultimately secured Baudrillard’s position as a major contemporary thinker whose significance continues to grow unabated.1

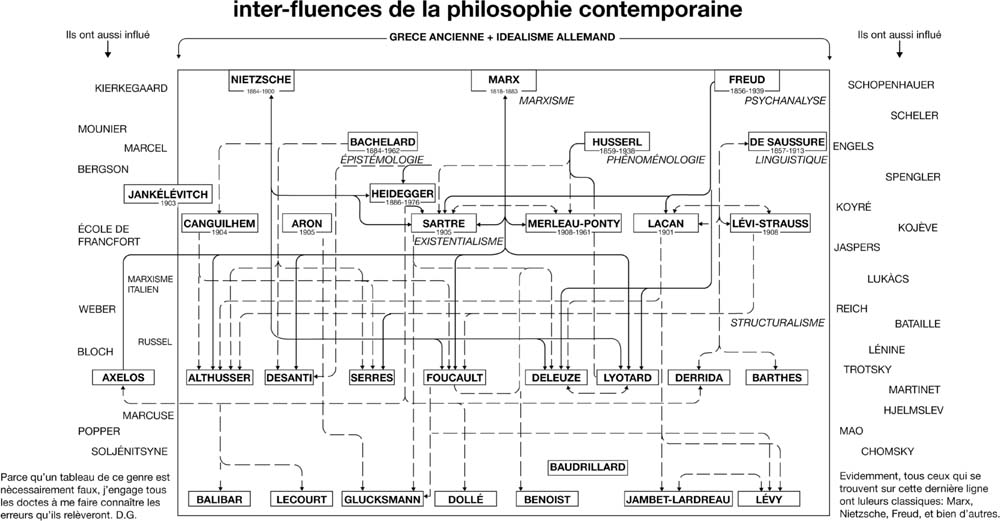

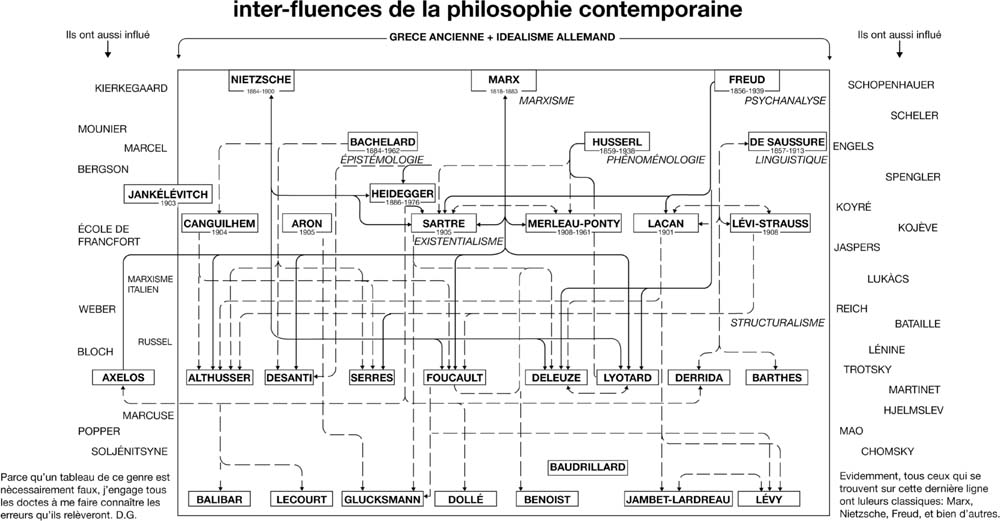

In 1977, a double-page spread in the Magazine Littéraire (Figure 1) featured Dominique Grisoni’s attempt to visualise the complex network of influences connecting leading French thinkers to each other and to the wider intellectual milieu of continental philosophy (Grisoni 1977). Resembling an electrical circuit diagram rather more than a family tree, it nonetheless positions three founding fathers – Nietzsche, Marx, and Freud – at the apex of a web of interconnections that encompasses some thirty key thinkers and spans a range of philosophical traditions. What is striking is that Baudrillard is already visualised as entirely disconnected from the network: out of the game, unplugged, with no arrows connecting him to any other thinker. 1977 was the year of publication of Forget Foucault (Baudrillard 2007), a succès de scandale which saw Baudrillard spectacularly sever his ties with the tightly knit world of French academe and burn his bridges with philosophy. ‘I make no claim to the title of philosopher. The history of ideas doesn’t interest me; it’s had no determining influence on me. I may have written a few conventional analyses . . . But then it turned into something else’ (Baudrillard, in Smith and Clarke 2015: 57). The interviews that follow fall under the category of ‘something else’. Whilst one might pin any number of the abiding conceptual terms that emerge from Baudrillard’s oeuvre on the selection we have made for this volume – terms that constantly recur, evolve, and mutate; such as reversibility, seduction, or duality – we have elected disappearance as the term best suited to establishing some consistency to what follows. The disappearance of culture might be seen as an irreducible element in a collection that traverses themes as disparate and wide-ranging as terrorism, art, politics, photography, evil, value, war, architecture, and so on.

If disappearance implies, on the one hand, an entropic process of dissipation, a viral process of contagion, a metastatic process of proliferation, or the affine redundancy of fractal geometry, there is, on the other hand, an art of disappearance. This is an art in which Baudrillard was well versed – knowing how and when to steal away, leaving events to exhaust themselves (whilst finding pleasure in the objective irony of ‘non-events’). Underlying this modus operandi is a fundamental recognition. Despite concerted efforts, over several centuries, to strip away the illusory appearances of the world and reveal the rational kernel of the real, the world’s furtive destiny remains remarkably unscathed. Attempts to force the unconditional realisation of the world, to impose a final solution on the enigma of the world, have redounded in the world poised to take its revenge. A fatal reversibility has taken hold, as the forced realisation of the world engenders an excess of reality, ushering in a state of hyperreality that short-circuits the distinction between the real and its double: even ‘The image cannot imagine the real any longer, because it has become the real . . . it has become its own virtual reality’ (Baudrillard 1997: 12).

Figure 1 Dominique Grisoni’s ‘Inter-fluences de la philosophie contemporaine’ [Inter-fluences in contemporary philosophy] (Grisoni 1977).

This liminal reversibility features in an Arthur C. Clarke story, which Baudrillard never tired of repeating. In the story, the Tibetan monks’ interminable task of listing by hand the nine billion names of God, which has proceeded since time immemorial, receives a technological boost from IBM. As a consequence, the list is completed in a matter of months. The computer technicians hurriedly take their leave, wishing to avoid a scene when the monks discover that the ancient prophesy motivating the task goes unfulfilled: the enumeration of the names of God was meant to mark the point at which the world will be complete and, having fulfilled its destiny, come to an end. It is the technicians, however, who find the certainty of their own beliefs shattered: as they descend the mountains from the monastery, they see the stars fade away, one by one.

For Baudrillard, the production of the real invariably succumbs to the superior principle of seduction, a principle that was once central in determining our symbolic relation to the world, but which modernity sought to annihilate. It is this principle on which Baudrillard banked:

Unlike the discourse of the real, which gambles on the fact of there being something rather than nothing, and aspires to be founded on the guarantee of an objective and decipherable world, radical thought, for its part, wagers on the illusion of the world. It aspires to the status of illusion, restoring the non-veracity of facts, the non-signification of the world, proposing the opposite hypothesis that there is nothing rather than something, and going in pursuit of that nothing which runs beneath the apparent continuity of meaning. (Baudrillard 1996: 97–8)

A remarkable resonance with Baudrillard’s theoretical disposition is to be found in Sophie Calle’s Suite vénitienne, an artwork premised on her secretly following a stranger she had met by chance in Paris. Pursuing him to Venice, Calle surreptitiously traces his movements, furtively photographing his encounters with others. Yet by these very acts, Calle finds herself unintentionally annulling the intentionality of his actions, inadvertently disclosing the senselessness of the world. ‘You seduce yourself into the other’s destiny, the double of his path, which, for him, has meaning, but when repeated, does not. It’s as if someone behind him knew that he was going nowhere’, says Baudrillard (Calle and Baudrillard 1988: 76–7).

In Paul Auster’s (1992) novel, Leviathan, Maria Turner – Calle’s thinly veiled fictive double – undertakes an identical project, displaced from Paris and Venice to New York and New Orleans. Remaining hidden as she secretly tracks her target’s movements and photographs his activities, Turner similarly reveals the seductive force of what remains hidden or, one might say, reveals the hidden force of the seductive. Auster (1992: 64) proposes that the experience ‘left her feeling that she had abandoned her life for a kind of nothingness, as though she had been taking pictures of things that weren’t there’. Baudrillard’s own photographic practice – which, he maintained, was quite distinct from his theoretical work, although others have remained unconvinced on this score – also proceeds according to a process of disappearance, a process of subtraction or abstraction from the world, from which subjectivity itself withdraws. Auster (1992: 64) proposes that, for Turner – his fictive counterpart of Calle – ‘The camera was no longer an instrument that recorded presences, it was a way of making the world disappear, a technique for encountering the invisible.’ For Baudrillard, photography allows the otherness of the object to transpear (‘shine through’), marking its distance from the subjective dimension intrinsic to writing.2 Whilst Baudrillard’s point is well made, this otherness, this radical alterity, remains very much what is brought in play in Baudrillard’s theoretical experimentation.

Baudrillard’s insistence on the double game of appearance and disappearance, production and seduction, man and woman, reality and illusion, good and evil, is played out in a world destined to deflect every effort to grant it meaning, imbue it with a sense of direction, and turn reality into its principle. Where acquiescence to the superior principle (enshrined in the second term) once formed part of an agonistic symbolic universe, in which challenge, illusion, sacrifice, and destiny held sway, on the far side of modernity, these notions only persist as the system exacts its revenge. Take the mode of disappearance, for example. In contrast to the mode of mortality – the finality and irreversibility of death – ‘What has disappeared has every chance of reappearing. For what dies is annihilated in linear time, but what disappears passes into a state of constellation. It becomes an event in a cycle that may bring it back many times’ (Baudrillard 1990: 92). When so-called savage societies practised sacrifice, this ritually enacted a means of exchange between the living and the dead, an affirmation of the cycle of life and death in which death inevitably held the upper hand. ‘There is’, Baudrillard (1993b: 126) proposes, ‘an irreversible evolution from savage societies to our own: little by little, the dead cease to exist.’ Death has increasingly become segregated from life, such that the dead no longer find a place amongst the living. Death now offends the sensibilities of the living: our dedication to annihilating death marks our distance from a symbolic relation to the universe. Yet never before have we been more surrounded by or preoccupied with death. This is obvious in the technological advances of digital war. It is also evident whenever medical science routinely announces the next big breakthrough that will ‘save another x thousand lives’, and which can only mean ‘defer another x thousand deaths’. Our bid for immortality is meaningless. Far from severing the symbolic bond between life and death by placing death out of bounds, ‘fighting . . . dying turns into the meaning of life’ (Bauman 1992: 140). The attempt to cheat death in the name of eternal life produces a ‘lethal transfusion in which each loses its specificity’ (Baudrillard 2005a: 125). The same consequence follows from every attempt to annihilate the superior principle of reciprocal terms. This fatal transfusion is evident throughout our culture – in terms of good and evil, for instance, where ‘friendly fire’ incidents offer a minor but telling example of the inability to eradicate evil in the name of good, and of the tendency for a liminal reversibility to accompany all such efforts. There is a kind of secret complicity which takes us hostage.

No longer is there a sense that politics or art confronts or challenges the real: thus, ‘art immerses itself in reality instead of becoming the agent symbolically assassinating reality, instead of being the magical agent of its disappearance’ (Baudrillard 2005b: 96). Art, like politics, becomes fascinated by the spectacle of its own disappearance. This fascination is, perhaps, the hallmark of our culture, both the medium and the message of its disappearance. The fatal indifference of the masses, induced by the system and destined to destroy it, signals both the degree-zero and the destiny of culture:

Previously revolutionary passions existed, but they emerged from the people, from a structured group, whereas the mass as such is not passionate about anything anymore nowadays apart from free fascination. The initial project of Beaubourg, the collective ideal, was devoured by its own success, through massive convergence towards this insoluble, illegible object. It is a mode of fascination at the same time as being a mode of the disappearance of culture (Baudrillard 1981: 69, our translation)

From overconsumption to electoral indifference, the fatal strategies of the masses – too compliant, hyperconformist, pushing the system beyond its limits and bringing it to its knees more readily than any form of direct opposition or active resistance – pose the challenge ‘of the reversion exerted on the whole system’ from within: ‘it is by their very inertia in the ways of the social laid out for them that the masses go beyond its logic and its limits, and destroy its whole edifice’ (Baudrillard 1983: 47). The masses, like Nietzsche, and like Baudrillard himself, are more than happy to push that which wants to fall.

ORGANISATION, SELECTION, AND BIBLIOGRAPHIES

There are five main points to note with regard to this book’s organisation. First, interviews already available in English (whether in translation or originally conducted in English) appear in chronological order according to their publication date in English, even though this occasionally introduces some interesting anachronisms. New translations to this volume are ordered by their original date of publication in French, and are intercalated into this chronology, which ranges from 1968 to 2014. Second, unless otherwise indicated, the interviewer(s) for each interview also undertook the English-language translation (this self-evidently excludes interviews originally conducted in English). Third, any accompanying notes, other than those deriving from the original, are ours, unless explicitly attributed to the translator(s). Fourth, we have given a title to each interview that originally lacked one and have instituted a new title in a limited number of cases, typically where overly generic titles (along the lines of ‘Interview with Jean Baudrillard’) have rendered this desirable. Finally, certain emendations have been made without note in order to impose a degree of consistency, in line with Edinburgh University Press’s house style, or to correct obvious errors, such as typographical errors or occasional mistranslations in earlier published versions.

There are a number of points to note in relation to the selection and inclusion of the interviews and dialogues comprising the volume. First, as noted, we have interpreted the term ‘interview’ both literally and liberally, to include a diverse set of exchanges and discussions that reach beyond the narrow definition of the term; a corollary of this is that, for purposes of clarity, we have adopted a slightly different format in the case of three panel-style dialogues (Interviews 1, 6, and 18). Second, whilst a version of Interview 9 is included in a Semiotext(e) collection (Baudrillard 2005b), the present volume includes the original translation of that interview. Third, a shorter version of Interview 17 has previously been published in English. Given the limitations of the previous translation, the present volume includes an entirely new translation of the full-length interview from the original German, which therefore comprises one of six new translations the volume includes. Fourth, we have systematically excluded more discursive pieces which report on interviews with Baudrillard, typically including selected quotations but departing from the interview format per se: such work extends to newspaper articles (for example, Hamilton 1994), book chapters (Rambali 1990), and magazine features (Beard and McClellan 1989; Grisoni 1985; Horrocks 1996; Leith 1998; Tanase 1984). Finally, we have resisted the temptation to include any of the ‘simulated’ (spoof) Baudrillard interviews that are in circulation, in magazines (Collings 2015), newspapers (Genocchio 2001), and online (Outward from Nothingness 2012), their existence being something to which the unwary researcher should remain alert.

We have also taken the opportunity to include a bibliography of ‘Select Books on Jean Baudrillard in English’, featuring more than fifty books that have been published in English about Baudrillard.3 This is not exhaustive and excludes, for example, some works of misdirection, such as Home (2001) and Powell (2012). We also include a bibliography of ‘Select Journal Special/Theme Issues/Sections on Jean Baudrillard in English’. These bibliographies are intended to serve as a guide to the ever-expanding literature on Baudrillard for the English-language reader. The literature available on Baudrillard in English is, of course, only a fraction of the total available commentary. Books about Baudrillard have been written in many languages – from the first full-length book published on Baudrillard’s work, which is only available in Dutch (Gils 1986), to the many books that continue to be published worldwide – for example, in French, German, and Italian: L’Yvonnet (2013), Danesi (2014), Sauvageot (2014), Penot-Lacassagne (2015), Latouche (2016), Poirier (2016), Strehle (2012), Heinrich (2015), de Conciliis (2009). New works by Baudrillard have also been published posthumously, for example, Guillaume (2013), Baudrillard and Derrida (2015).

NOTES

1. Baudrillard’s legacy has been given thoughtful consideration by Merrin (2008). Whilst the unfolding of world events continues to reinforce the significance of Baudrillard’s way of thinking, his ideas constantly invite renewed attention. In France, 2013 saw a conference commemorating Baudrillard at the National Library of France; 2014 witnessed a major conference celebrating his work entitled ‘Jean Baudrillard: l’expérience de la singularité’ at the Université Nanterre (renamed Université Paris Ouest Nanterre La Défense); and 2016 saw the inauguration of ‘Les archives de Jean Baudrillard’ at L’Institut mémoires de l’édition contemporaine (IMEC), the Institute for Contemporary Publishing Archives based at Ardenne Abbey. Elsewhere, the Taipei Fine Arts Museum held a major conference on ‘Baudrillard: Thought and Art’ (see Chih-ming 2015), and Baudrillard’s photographs continue to be exhibited and discussed worldwide, a point to which we return.

2. The two main published collections of Baudrillard’s photography are Baudrillard (1998a) and Baudrillard (1999). The first major exhibition of Baudrillard’s photographs was in Paris in 1992. Exhibitions followed not only in France but across the world – for example, in Venice (1993); Brisbane, Sydney, Adelaide, Melbourne (1994; Baudrillard 1994; Zurbrugg 1997); Rio de Janeiro (1996); Tokyo (1997); Leicester (1998; Baudrillard 1998b); Graz (1999); Auckland (2001; Byrt 2001); Sydney (2001); Paris (2001); Moscow (2002); Siena (2003); Kassel (2003–4); Izmir (2004); Karlsruhe (2004); Seoul (2005; Descoueyte 2005); and continued after his death: for example, Lianzhou (2010); Guangdong (2012); Macau (2013); Taipei (2014); and Los Angeles (2015–16; Abrahamian 2016).

3. For a bibliography of Baudrillard’s books in English, see Smith, R. G. and Clarke, D. B. (eds) (2015), Jean Baudrillard: From Hyperreality to Disappearance, Uncollected Interviews, Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, pp. 197–9.

REFERENCES