The didn’t travel light, like a refugee with two emeralds sewn in her underwear; twenty-eight pieces of luggage went with Josephine to North Africa.

The crossing was a misery, the Mediterranean wild and choppy, the animals panicked as they ran between wardrobe trunks waltzing around the cabin.

And in Algiers, more aggravation. A policeman armed with a subpoena met the boat. The Marseille Opéra was suing Josephine for having “scandalously abandoned La Créole.”

She couldn’t believe it—“I would have to pay 400,000 francs in damages before I could enter Morocco!”—but had to stay behind while Jacques went on to Casablanca.

Happily, she discovered the Merlins were in Algiers. Jean was running the St. George Hotel (which would become General Eisenhower’s headquarters after the Americans landed), and Odette was trying to become pregnant. Wanting a second—or fiftieth—opinion about whether or not she could conceive a child, Josephine visited Odette’s gynecologist. As usual, the answer was no.

By the time she reached Casablanca, on January 28, there was more bad news. The consulate of Portugal would give Josephine Baker a visa, but refused one to her ballet master.

Abtey and Josephine wondered if his cover had been blown. “We decided,” she said, “that I would have to travel to Lisbon alone. Taking my sheet music, of course.” A month later, she boarded a train from Casablanca to Tangier, first stop of her journey. Tangier was neutral, an international zone, filled with spies and money, and there Josephine spent a few days with Abderahman Menebhi.

During earlier times in North Africa—Princesse Tam-Tam had been shot in Tunisia and Tangier, and she had given concerts everywhere—she had made many highborn friends, most of them related by blood or marriage to Mohammed V, sultan of French Morocco. Abderahman Menebhi was one of these. And in his palace on a hill overlooking the sea, she found herself reunited with some of the others, including Ahmed Ben Bachir, court chamberlain to the caliph of Spanish Morocco.

His son, Bachir Ben Bachir, says the feeling between Josephine and his father, whom she had met in 1935, “developed into a physical relationship” during the war. “My father could not speak French, but she could speak Spanish. She often spent time with him at his palace in Tetouan, where she met Spanish government officials. She taught the high commissioner the merengue and also passed information from the Americans to my father, and my father tried to convince Franco to let the Americans use the Spanish Sahara as a military base.”

But that would come later. Now, even as Josephine arrived in Lisbon with her music scores for Captain Paillole, General Rommel’s troops were marching into Libya.

“The pro-Germans were jubilant,” she said, “the rest of us heartsick.” From Lisbon, says Bachir Ben Bachir, “she contacted my father and told him she needed a safe-conduct pass to give her more flexibility. She got the document, and with it, could go all over the world, even to America.”

Where she went with it was to Les Milandes, still in the Free Zone. Henri Chapin, who had escaped the Germans and come home to Beynac, was now working at the château as an electrician, along with his friend Coudert, a stonemason. “From time to time during the war,” Chapin says, “Josephine would arrive to see what we had finished, and tell us what else she wanted done.

“In the kitchen of the château was a big table, and she would come with a suitcase full of money, bills of all different currencies, and she would dump it out on the table and say, ‘What do I owe you? Pay yourselves, and keep the accounts straight.’ And she would be walking around totally naked. At the beginning, we were very surprised, you know, we were young men, but then we got used to it.”

Even on a flying visit, she managed the odd escapade. “One of her lovers would come on a motorcycle,” Georges Malaury remembers. “And he would hide it in a wooden shack down the road. But there was no gasoline during the war, so while he was with Josephine, the local guys would go siphon off the gas. What’s he going to say? ‘While I was having sex with Josephine, somebody stole my gasoline’? And he was doing black market, so nobody felt sorry for him.

“My father was in the underground, he had a radio transmitter in the tower of the château and he transmitted to England. One time the Germans came—Josephine had just arrived—and she greeted them in German, saying, ‘There’s no maquis here, I’m Josephine Baker, let me entertain you.’

“They later killed the chef de gare of the railroad station, poor man. He said, ‘I was in the first war against your country, I have a wooden leg, fuck you,’ so they shot him.”

In Lisbon again, Josephine found that posters advertising her concerts were plastered everywhere. She stayed in the city through March, gathering documents by day, and by night singing to sellout crowds that provided her with much-needed cash. (She couldn’t get funds from Monsieur Bondon in Paris; it had become as difficult to move money as it was to move human beings.)

Then she returned to Morocco, messages from Paillole fastened in her bra with safety pins.

Although she came close to death there, I think the years in Morocco were among the happiest of her life. It was a country that had always been, in the words of the British writer Gavin Maxwell, “xenophobic and mysterious, guarding splendors and horrors that the wildest travellers’ tales could not exaggerate.” (Among those tales were accounts of salted human heads displayed in public.)

By 1912, most of Morocco (except for a few Spanish enclaves, including the ports on the Mediterranean) had become a French protectorate, but it remained a land out of the Arabian Nights. And wasn’t it queer that Josephine, who had spent her childhood dreaming of kings in golden slippers, should find herself there? In a place where, even more amazingly, racial discrimination did not exist? Thami el Glaoui, pasha of Marrakesh and the most powerful tribal chieftain in French Morocco at that time, was himself black.

“Most harems in Morocco had women of all colors,” says Bachir Ben Bachir, “and their children were recognized by their fathers, with full inheritance rights.”

Yet I wonder what Josephine thought about the rights of those Moroccan women confined, no matter what their color, to seraglios? For that matter, what did those women think of her, a female sitting down to dinner with the men? A female untrainable as a wild bird in the art of subservience?

In Marrakesh, she could not stay with her old friend, El Glaoui, though he had offered her his hospitality many times before the war. Mohamed Hedidech, now chief concierge of the Hôtel Minzah, still remembers how, sixty years ago, Josephine’s arrival would thrill the whole city. “She was so beautiful,” he says. “She would come by boat to Tangier and stay overnight at the Minzah, and next day, two Rolls-Royces would be waiting outside, one for Madame, the other for her trunks. El Glaoui liked pretty women, and he was generous.”

That was all Josephine required of a man, but in 1941, the pasha was in the thick of political intrigue. The French were asking for his allegiance, the Germans pushing for revolution. It was no time to renew romance with such a famous—and outspoken—partisan of France. Nor to have her as a live-in guest. Instead, El Glaoui sent her to the palace of his brother-in-law, Moulay Larbi, which proved to be embarrassing for that gentleman. Because every morning, as soon as the birds started singing, Josephine was up and running around in the buff, going to the kitchen to help the servants cook.

A very old lady named Mabrouka (still employed by Moulay Larbi’s daughter Kenza) told me that Josephine loved chicken feet, and her laugh was “crystal clear, like a little child’s.”

But for Moulay Larbi, a religious Muslim, it was a danger to have this bare-skinned houri flying through the halls. (Even in the fifties, after the sultan had converted the state to a constitutional monarchy and changed his title from sultan to king, there were riots when one of his daughters appeared on a beach in a bathing suit.) So Moulay Larbi begged Mohamed Menebhi, yet another of his brothers-in-law, to rescue him. And Mohamed Menebhi offered Josephine the use of a little house he owned in the medina.

Of all the Moroccan aristocrats who lavished favors on her, Mohamed Menebhi is probably the only one Josephine didn’t sleep with. And probably the one who loved her most. She had affairs with his brother Abderahman (she had even wanted to marry him), with El Glaoui, with Ahmed Ben Bachir, with Moulay Larbi. But not with Mohamed Menebhi.

“Magnificent,” Jacques Abtey calls him. “Not good-looking, he was small, with an ungrateful face, but noble in his way of behaving, and he gave all his heart to the Gaullist cause.”

Or most of it. He reserved some part for Josephine.

Forty years later, accompanied by Mohamed Menebhi’s eldest grandson, Aziz, I visited that little house in the medina. For me, it was like walking up to the front door of Pa Baker’s restaurant in Philadelphia, I was convinced I was feeling what Josephine must have felt.

The medina is the heart of the old city, and in its narrow alleyways, women passed silently, their faces masked except for eyes that burned through us like X rays. Aziz led me through a wooden door into a patio open to the sky, water splashing in a white marble fountain. Four rooms surrounded the courtyard; one still held Josephine’s big brass bed from France.

It was here she had settled in with Jacques Abtey, and adopted Arab customs. She liked eating with her hands, wearing the loose djellaba, going with her maids to the hammam, the Turkish baths, once a week.

“There were three orange trees perfuming this oasis,” Jacques Abtey recalled. “We found there the serenity that detached soul from body.”

But a little serenity went a long way with Josephine. At the beginning of May, Moulay Larbi came by with the news that Morocco might be invaded by German troops. Abtey remembers that Josephine’s pet monkeys were jumping from one orange tree to another when she announced, “I should go to Spain and perform there.”

She toured Seville, Madrid, Barcelona, deluged with invitations wherever she landed. “Embassies, consulates, full of interesting people. Coming back to my hotel room, I made careful notes.” As before, the notes were pinned to her underwear. “Who,” she asked rhetorically, “would dare search Josephine Baker?”

Before returning to Marrakesh, she stopped again in Tetouan to see Ahmed Ben Bachir. “Every time she could get away, she came,” says Bachir Ben Bachir. “She liked to have a tent pitched by the seaside, and drink tea, while musicians played and cooks barbecued lamb. She would swim, run back into her tent, and my father would entertain her. She was a courtly mistress, and she wanted the whole treatment. She asked my father to have his soldiers turn their backs the minute she stepped out of the house. Until she got into the car and dashed off with him.

“He was a bachelor then, about five years younger than she. He put a private Turkish bath in his house because she loved Turkish baths. She used to drink raw eggs after the bath, it was Moroccan tradition. She lived her fantasies there, and always, she had the urge—you can tell from her letters—to get back to my father because he made her feel like a woman, and for a time she could be divorced from the war.”

She wrote to him when they were apart, asking favors, giving instructions. “Could you send me a visa for my maid, Paulette, still in France? . . . and do not forget to feed the horses, those poor animals could starve to death.”

Amused by that particular note, he wrote back that the horses had got an extra pail of oats in her name, and that he was sorry not to have been with her at a recent concert “to admire your delicious temper.”

But, his son recalls, Ahmed Ben Bachir was also very useful to Josephine in her other life. “She developed a network by which she secured Spanish Moroccan passports for Jews who were coming into the Spanish zone; my father used to go to the high commissioner and say they were Moroccan Jews, but they were really Eastern Europeans who would get passports and go to Latin America. Josephine helped a Rothschild lady in Tangier.”

Once, on her way home from Tetouan and a rendezvous with Ahmed Ben Bachir, Josephine stopped in Casablanca for a consultation with yet another gynecologist. I have been told by Dr. Georges Burou (who attended the royal family of French Morocco) that this man was a charlatan. “He performed a procedure which consisted of blowing air into Josephine’s fallopian tubes. He also gave her an injection of Ipedol, a very debilitating drug. After that, he should have prescribed a total rest; instead, he sent her back to Marrakesh, a 350-mile journey, on the very poor roads of that time. And she developed peritonitis.”

Not knowing how sick she was, she returned to find that she and Jacques had a houseguest, Bayonne, their colleague in the underground. He was still there two days later when Josephine was seized with terrible pains in her belly. Bayonne fetched ice, Jacques held her hands, but it was clear that she needed to be in a hospital. Not in Marrakesh, but in Casablanca, which had better facilities.

“I went out,” Jacques said, “and borrowed a station wagon for Josephine to lie down in. At the Municipal Hospital in Casablanca, the head nurse insisted that Josephine get out of the car and walk. ‘You are crazy!’ I screamed at her, and asked our chauffeur if there were another place. He said yes, the private clinic of Doctor Henri Comte, two streets away.”

It was the end of June 1941, and she would not be released from the Comte clinic until December 1, 1942. Her fanatic determination to have a child had driven her to consult so many quacks, to try so many risky treatments, that finally the poor body had rebelled.

“I assisted my friend Comte with that first operation,” says Dr. François Bolot. “Josephine had an abscess between the bladder and the genitals. Comte lanced the abscess, and put in a drain. A few days later, Comte had to go to France, and I supervised Josephine’s postoperative care.

“The French captain Abtey often slept on a cot in her room, and when her fever would rise, he would run to get me. He was blond, he had a nose shaped like a saber blade, and I always distrusted him, because in time of war you distrusted everyone, and I was always wondering if he had been put there by the Gestapo or the French police.

“Josephine told us that her ancestors had lived in Louisiana and that after Napoleon sold that province to the Americans, they had moved to the Antilles so they could stay French.”

Josephine wrote to Ahmed Ben Bachir, saying she could not come to him for the August vacation they had planned. “I’m heart-broken. Today, with fever and being in bed, I’m skinny like a skeleton, and it is better that you don’t see me like that. When I come out of the clinic, I will go to rest at Les Milandes.” At the time she scrawled these lines, she expected to be sent home in a couple of weeks.

“During those long days,” Jacques Abtey says, “Josephine read a lot. She was very impressed by the lives of Louis XIV and Napoléon. When someone compared Napoléon’s armies to Hitler’s, she would get furious. “I like great monarchs! Napoléon was a genius, Hitler is a crazy person.”

Right across from the Comte clinic was the Parc Murdoch, filled with flowers and shadows and palm trees, but Josephine was still too fragile to venture out. “They operated on her so many times,” Jacques Abtey says. “Once she asked the doctor, ‘Why don’t you just put a zipper in? It would be so much easier.’ ”

She never lost her humor; when a priest came to give her last rites, placing his crucifix across her chest, she laughed. “Not yet, Father.” Doctors, nurses, strangers, were always stopping by to see her. (I often wonder if her many relapses were due to the fact that she was seldom quiet except when she was unconscious.) Even her ex-husband, Jean Lion, appeared. He had been fighting in Tunisia with the French army—he would eventually receive the Croix de Guerre—and Josephine put on jewels and makeup to look beautiful for him.

The sickroom served as a perfect cover. What could be more natural than for American diplomats to come pay their respects to an American-born artist? And to meet, at her bedside, Moroccan leaders? And to discuss German intentions toward Morocco? And the Free French invasion of Syria? And when the Americans might land in North Africa?

On December 7, Japan attacked Pearl Harbor, crippling the American fleet. On December 10, Germany and Italy declared war on the United States. On December 13, Hungary and Bulgaria did the same.

Christmas 1941 was not festive, but Jacques tried to spread cheer, bringing to Josephine’s room a tiny tree and dressing it with little candles, red, yellow, green.

She was beginning to feel stronger, and one day he took her for a carriage ride. Muffled in a fur blanket, only her hands outside, she put one of them on his. “Look how beautiful your color is,” she said. It distressed him, as it had distressed Ralph Cooper on that long-ago summer afternoon. “She hated the color of her skin so much, it made me feel terrible for her.”

But even as Josephine continued to suffer over her blackness, her life, as compared to the lives of some of her old acquaintances, was charmed. In occupied Holland, Evelyn Anderson was interned by the Nazis, then sent to Germany. “I was dancing with my partner Harry Watkins at the Zuid,” Evelyn recalls. “It was a cabaret in the Hague, and when the Germans came, Harry said, ‘If you see a dark cloud passing by, you’ll know it’s me running.’ ”

He couldn’t run fast enough. He was deported. “And the man that used to own the Zuid, he was Jewish, and they sent him away, and Papa Toby that ran the pension where I lived, they took him away too, and then they came and got my friend Ida Johnson and her two children and myself.”

Ida’s husband, Freddy, an American pianist, had been taken first. “The Germans told him they were picking up all American men regardless, black or white,” Ida said, “and all he could take was a toothbrush.”

Marilyn Johnson, Ida’s then sixteen-year-old daughter, remembers saying goodbye to her father at the train station. “We were crying, he was very calm, but he was frightened. He said, ‘I don’t know whether I’m going to see you all again, but keep a stiff upper lip, and if I get a chance, I’ll write.’ ”

“When the Germans first occupied Holland,” Ida says, “we would lie in bed at night and hear the footsteps of the soldiers taking the Jewish people away. They came in the middle of the night. The only reason they tolerated us was because a lot of Germans had never seen any black people. They’d rub you to see if the color came off you.”

Ida, her daughters, and Evelyn were soon removed to another camp in Holland. “They were killing Jews there,” Marilyn says. “I saw men kicked to death by German boots with the metal spikes. They did not fight back, and I couldn’t understand. My mother used to worry because I believed in speaking my mind. If I saw an old man, a skeleton with cheeks and eyes sunken, and the Germans were kicking him, I would yell, ‘Stop it!’ and my mother would grab me and pull me aside with a hand over my mouth.

“I’ll never forget it. Kicking an old person until he died. And these were young, most of the German soldiers, fourteen, fifteen. I talked to one of them once, he was crying and saying, ‘I miss my mother, I’m afraid.’ ”

Later, in Germany, Evelyn and the Johnsons were held in a convent in Liebenhau.

In 1942, the world was exploding. Americans fought at Bataan, Midway, Guadalcanal; Germans slogged through Russia, reaching all the way to Stalingrad; the British beat Rommel at El Alamein.

But all continued calm at the Comte clinic. On the arm of her devoted nurse, Marie Rochas, Josephine was now able to walk in Parc Murdoch. Mohamed Menebhi brought her lemon chicken. Jean Gabriel Domergue (who had painted her portrait for the cover of the Folies-Bergère program in 1936) came to visit and was horrified to see she had lost fifty pounds. “Ah,” he said, “your beautiful buttocks have disappeared.” A crowd of locusts flew in through the window, and when Marie tried to stamp on them, Josephine screamed and called her a murderess. An American vice-consul named Bartlett stopped by to say how happy Washington was with the material Captain Abtey had been supplying.

In August, Maurice Chevalier appeared, but Josephine refused to see him. “He is a great artist,” she said, “but a very small man.” (She would later accuse him publicly of being a Nazi collaborator.)

Back in Paris, Chevalier, his pride wounded, made up a story that spread like a brushfire: the dying Josephine had clung to him, saying, “Maurice, do not abandon me.” The German-controlled French press printed that she had syphilis, and Josephine wrote to the Guignerys at Le Vésinet. “Thank God all those reports are big lies, I ask myself why people amuse themselves with such ugly stories, and I beg you to tell our friends not to pay any attention to them.”

She wrote to the Rivollets as well. “She sent us postcards telling us alarming news,” said André, “with gynecological details and a total lack of modesty. The post-office employee blushed.”

In October, she found a stray cat, for whom she knit a sweater. “It is God who sent him to me,” she said. Vice-Consul Bartlett was called home, but before he left, he told Jacques and Josephine, “It won’t be long now, we are coming in considerable strength.”

They came on November 8, a huge force of Americans and British disembarking in Casablanca, Oran, Algiers, from five hundred warships and cargo ships under air support from Gibraltar. Once the Allied troops landed, Hitler and Mussolini hastened to occupy all of France, there was no Free Zone anymore.

Because the political situation was so bizarre—“Marshal Pétain,” wrote Louis Snyder, “immediately ordered resistance and broke off relations with the United States”—French troops fought Americans in the streets of Casablanca.

“The Americans arrived on land where the French flag was flying,” said Jacques Abtey bitterly, “and they were welcomed by machine-gun fire.” Abtey resolved to report to American headquarters—he hoped to be received by General Patton, but this did not happen—and Josephine wanted to go with him, but he said no. He drove from the French sector to the American sector in a borrowed ambulance, flying the flag of the Red Cross, and all along the roads, he passed dead soldiers. “The first I found was Senegalese, he died as a servant of Hitler, not knowing the French had used him. After that, two Frenchmen . . . then the first American. Death had not disfigured his adolescent face. He was lying with his arms crossed over his chest. . . . I turned my head away, I was ashamed to be French.”

Three days later, all was sunny again, there was a military parade with troops—American, French, Moroccan—marching through Casablanca. “A reconciliation,” Jacques called it. Later, he and members of Paillole’s group went to Josephine’s room and drank champagne. “We raised our glasses to America, to England, and to our eternal France.”

Nineteen months after she had arrived there, Josephine was discharged from the clinic (Dr. Comte never gave her a bill) and returned to Marrakesh. This time, Mohamed Menebhi took her into his own palace, where she could be better cared for.

Now rumors of her dying turned into rumors of her death. The Chicago Defender had her breathing her last “in the city hospital at Casablanca, Portugal [sic]. . . . By her side . . . was her estranged Italian husband.”

And in an obituary written by the black American poet Langston Hughes, Josephine was called “as much a victim of Hitler as the soldiers who fall today in Africa fighting his armies. The Aryans drove Josephine away from her beloved Paris. At her death, she was again just a little colored girl from St. Louis who didn’t rate in Fascist Europe.”

“When I saw in a newspaper that my sister had died,” Margaret told me, “I ran home and tore upstairs to Mama’s place. She was sitting in a chair, staring out the window. ‘Mama,’ I said, ‘Tumpy’s dead.’ ”

Slowly, Carrie turned and shook her head. “Tumpy ain’t dead,” she said.

Freda J. McDonald? The only baby picture of Josephine Baker. But is it authentic? “Is that you, Mother?” (Courtesy Jacques Abtey)

Eddie Carson, one of Carrie’s lovers and believed by some to be Josephine’s father—but she knew better. (Courtesy Richard Martin, Jr.)

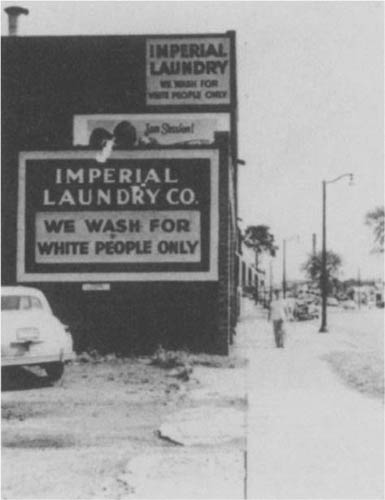

This sign was typical in Josephine’s youth and she saw it when she helped out at the Cooper’s laundry in St. Louis. It would fuel her rage. (John Vachon, Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, NYPL)

A wistful Josephine McDonald Martín Wells before she left St. Louis in 1921—with her lady lover, Clara Smith.

Clara Smith, billed as the South’s “favorite coon shouter.” Josephine could not have found a better singing coach. (Courtesy Frank Driggs)

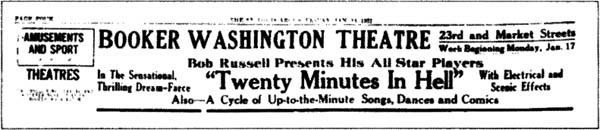

Booker Washington Theatre: the incubator of Josephine’s dreams. What she learned there, she could not have learned anyplace else.

August 1922, in Boston with Shuffle Along, looking like schoolgirls in their cotton dresses: second from left is Josephine; next to her are Ruth Walker, Mamie Lewis, Evelyn Sheppard (“Little Shep”), and her brother, Willie. No one remembers the identity of the man at left or the little girl.

The Honeysuckles on bended knee in Shuffle Along: “The preacher will be waiting when the knot am tied.” A smiling Josephine is fifth from left. (Courtesy Robert Kimball, Sissle-Blake Archives)

A sartorially splendid Josephine, long before Paris fashion claimed her. This photo was inscribed to Mr. and Mrs. Eubie Blake. (Courtesy Robert Kimball)

The entire company of Shuffle Along: Josephine is down front, second from right, a standout in taffeta and ruffled skirts—always a scene-stealer.

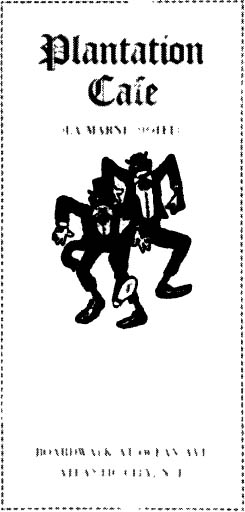

Program from the Plantation Cafe. Inset: Josephine clowns at Revere Beach, 1924, with Howard Nelson (center), violin, and Edgar Campbell, clarinet. (Courtesy Marion Cumbo)

Plantation Cafe, on the boardwalk, Atlantic City. (Courtesy Johnny Hudgins)

At the curtain call of Chocolate Dandies (1924), in the arms of Johnny Hudgins while Lew Payton looks on. “To be funny then, colored comedians had to cork up,” said Hudgins. (Courtesy Robert Kimball)

The great Florence Mills, the first black to headline the New York Palace Theatre, 1925. Josephine loved her, even when reviewers compared them—to her disadvantage: Josephine “. . . is a rat who kicks with so much spirit! The other is an island bird.” (Courtesy Joe Attles)

Maude Russell, the “slim princess” of the T.O.B.A. (Tough on Black Asses) circuit. Beautiful, talented, and unfailingly honest. “You learned a lot in those days, baby.” (Courtesy Maude Russell)

A random search in an old thrift shop brought this precious discovery: the Berengaria passenger list of Wednesday, September 16, 1925. The very date of Josephine’s departure for Paris—and destiny.

Josephine (foreground) looking like an urchin on the deck of the Berengaria during a mine alert, September 18.

1) Mabel Hopkins

2) Josephine Baker

3) “Jack,” an actor on his way to England

4) Spencer Williams

5) Maud de Forrest

6) Bea Foote

7) Marguerite Ricks (Courtesy Claude Hopkins)

September 22, 1925. “Bonjour, Paris!” La Revue Nègre in all its elegance at the Gare Saint-Lazare. (Courtesy Claude Hopkins)

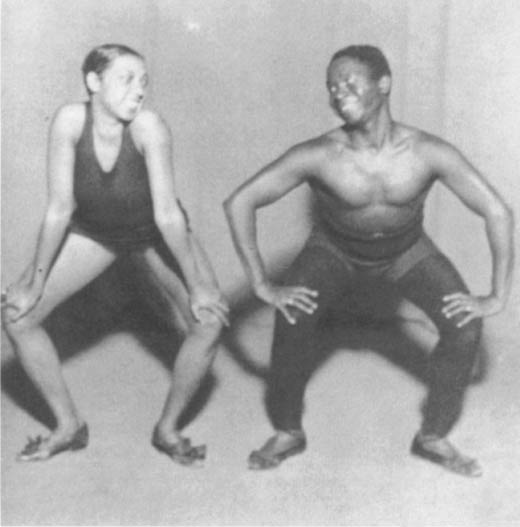

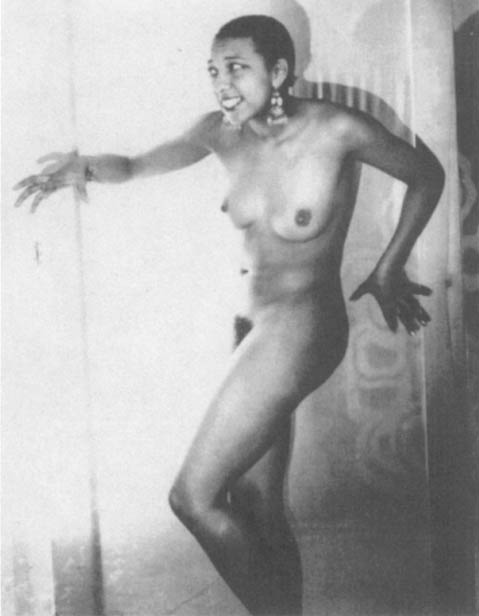

The calm before the storm. Josephine and Joe Alex rehearsing “La Danse de Sauvage.” “Barbaric . . . naughty . . . a return to the customs of the dark ages,” a critic would say. (Courtesy Claude Hopkins)

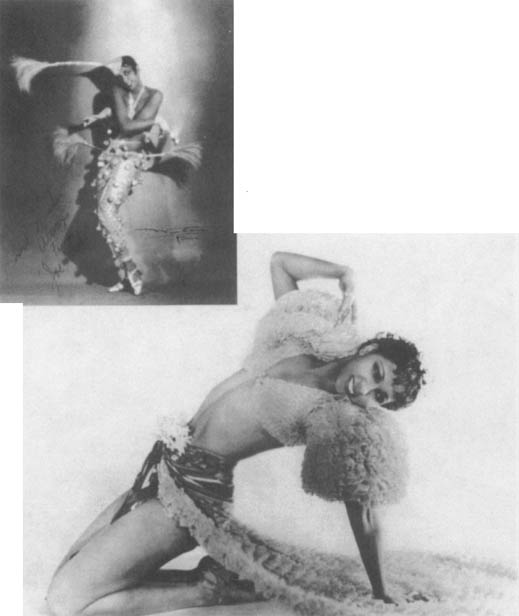

The famous banana costume from the 1926 Folies-Bergère. Many will claim to have invented it, but only Josephine would dare to strategically fashion herself a substitute phallus. (Roger-Viollet)

Imitating Johnny Hudgins in blackface, Folies-Bergère, 1927.

In the 1926 Folies-Bergère after emerging from her famous Crystal Ball. She never tired of looking at herself in a mirror. (Courtesy Shubert Archive)

A rare photo of Josephine flahing. The tigress is in her element, but who is she stalking this time? (Roger-Viollet)

Parodying the greate Pavlova. She never liked ballerinas on point. “They look like silly little birds . . . dreadful.” (Studio Piaz)

In 1932 at the Casino de Paris, singing “Si J’Etais Blanche” (“If I Were White”). She hated being black, but she never forgave whites for the racial injustices she had suffered at home. (Studio Piaz)

Do you have a light? Cross-dressing at the Casino de Paris. (Studio Piaz)

The “Electric” Fairy: Celebrating the modern convenience of electricity, Casino de Paris, 1930. (Roger-Viollet)

A 1927 Folies-Bergère pose inscribed to her friend Mildred Hudgins, whom she had first met in Philadelphia in 1921. Not all memories of home were bad. (Walery-Paris)

In Offenbach’s La Creole, 1934. Her introduction to the “legitimate” theater. “Now I spoke French,” she claimed, “at the side of strictly French actors.” (Studio Piaz)

First flying lesson with instructor Demay, 1935.

On her twenty-first birthday, she got her driver’s license.

Infectious joie de vivre draws a crowd on the streets of Paris, 1926.

From left to right, Mildred Hudgins, “Count” Pepito, and a friend celebrate with a pensive Josephine at Chez Josephine, her boîte in Montmartre.

On St. Catherine’s Day, when unmarried French girls don hats and search for husbands, she played the innocent virgin with designer Paul Poiret and his models. (Courtesy Christiane Otte)

A blooming Josephine, inscribed to her friend Miki Sawada. (Courtesy Emi Sawada-Kamiya)

A prickly version of the banana costume in the Ziegfeld Follies of 1935. Her return home was less than triumphant.

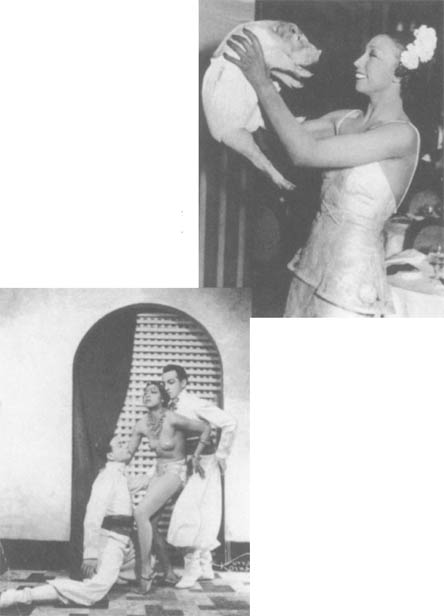

Josephine and her pet baby pig. She had a lifelong love of animals, from the exotic to the domestic.

The temptress in New York. She loved the photographer, Murray Korman, because he lit her so that she looked white.

On the train to Bordeaux, 1939, with husband, Jean Lion, and secretary. Josephine, chic and radiant, plays to her adoring crowd.

The star in war-torn France, knitting scarves for the soldiers at Les Milandes with Madame Bataille and her niece, July 1940. (Maurice Bataille)

Arriving in Paris from a South American tour, 1939, with friends and a menagerie of chattering souvenirs.

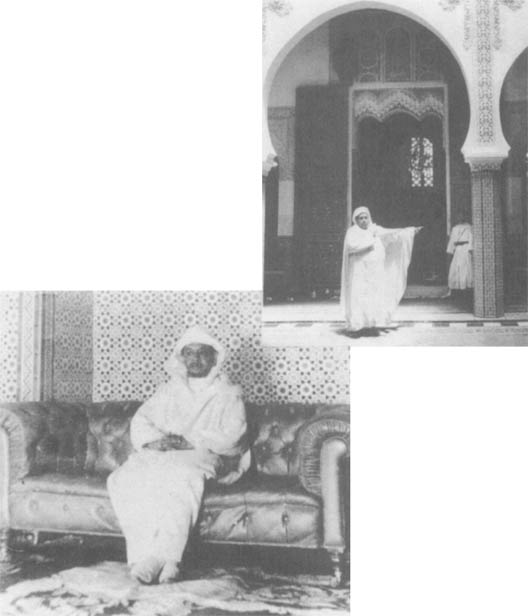

Thami el Glaoui, pasha of Marrakesh. (Courtesy Abdessadeq el Glaoui)

Ahmed Ben Bachir. (Courtesy Bachir Ben Bachir)

Mohamed Menebhi. (Courtesy Medhi Lamghari-Menebhi)

Casablanca, 1943, with Jacques Abtey and a friend. (Donald Wyatt)

Rehearsing before the opening of the Liberty Club, a Red Cross facility for black soldiers. Casablanca, February 1943. (Donald Wyatt)

With Major Donald Wyatt and friend. (Courtesy Donald Wyatt)

Richard Alexander Martin, who looked much like his half sister, Josephine, on duty during the war, in Great Lakes, Illinois. (Courtesy Richard Martin, Sr.)

Sublieutenant Josephine Baker on her way back from North Africa to a newly liberated Paris on a Liberty ship, October 2, 1944. Air Force officer Catherine Egger snapped the photo.

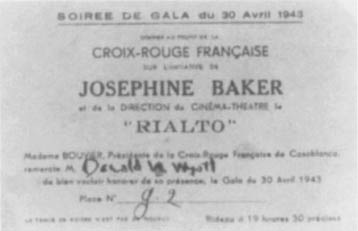

An invitation to the Rialto, Casablanca.

Soirée de Gala, starring Josephine and Frederic Rey.

Josephine is decorated with the Medal of Resistance on her sickbed in Paris. De Gaulle himself wrote to congratulate her and wish her a speedy recovery. “I would like to be upright to receive a medal from France,” she said. (France-Dimanche)

Avenue Bugeaud. she owned the building. (France-Dimanche)

Le Beau Chêne, Josephine’s villa at Le Vésinet.

Les Milandes in all its imposing splendor. (Paris Match)

At Place Josephine, the star in stone as the Virgin Mary blessing the tourists. (Arthur Prevost)

A tableau from the Jorama, a wax museum at Les Milandes: “Saint” Josephine with her husband, Jo Bouillon, being blessed by Pope Pius XII. (Courtesy Arthur Prevost)

Josephine with her glittering friends—Jean Cocteau, Mistinguett, Katherine Dunham, Jean Marais, and a dancer—at the opening of Dunham’s dance company, Paris, 1949. (Courtesy Katherine Dunham)

Josephine charming students at Fisk University in Nashville, 1947. (Courtesy Donald Wyatt)

Creating a furor in 1951 Havana with yet another new look with the help of hairdresser Jean Clement. (Courtesy Jean Clement)

Powdering her legs backstage in Cuba, a rare private moment getting ready for the public. (Courtesy Julio sendin)

Coccinelle, the most famous transsexual of France, with Marlene Dietrich. To Josephine, Coccinelle was always “my daughter” and Dietrich was always “that German cow.” (Courtesy Coccinelle)

“Thank God for making men like Perón,” said Josephine, here pictured in Buenos Aires, 1952, with her hero. (Courtesy Koffi and Diane Bouillon)

Members of the Rainbow Tribe with “Uncle Fidel,” Havana, 1966. (Courtesy Jarry Bouillon-Baker)

Newly decorated with the Legion of Honor and the Croix de Guerre with palm, Josephine stands at attention with Commandant Cournal at Les Milandes, August 1961. (France-Dimanche)

Josephine and daughter Stellina with Golda Meir in Israel, 1974. (UPI)

Carrie McDonald Martin Hudson gets a kiss from her first-born child backstage at the Folies-Bergère, 1949. (Courtesy Maryse Bouillon)

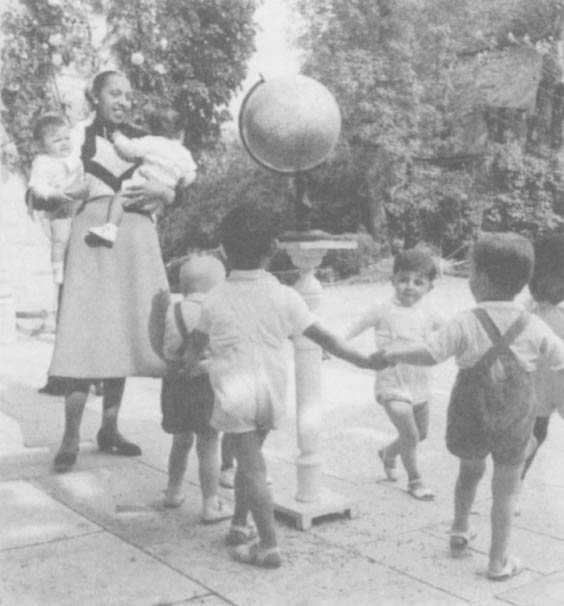

The self-crowned Universal Mother choreographing her dance of world brotherhood. Josephine holds in her arms Brahim and Marianne while looking down on Moise, Luis, Jean-Claude, Akio, Jari, and Janot. (Reporters Associés)

The Rainbow Tribe “protected” from the outside world but still on display at Les Milandes, the “Capital of Universal Brotherhood.” (Courtesy Arthur Prevost)

Lunch, en famille, in the kitchen of the château with the two “uncles,” Monsieur Marc and Monsieur Rey. Aunt Margaret is seated in front of the large American refrigerator. (France-Dimanche)

“A poor old lady alone in the rain.” A dream comes to an end. (Paris Match)

Luce Tronville, my natural mother. The virginal convent girl with the perpetually sad face and full heart.

Eleven-year-old “Yan-Yan” with my sisters, Marie-Jo, Marie-Annick, and Martine in St. Symphorien, 1954.

Josephine loved this faunlike portrait of me—and my natural mother was ashamed of it.

Bal à Tout Coeur, Cannes, 1973. At far left, that’s me in mod dress, Rama (Margaret’s daughter), a beaming mother, Marianne, Luis, and Janot. (Courtesy Hörzu)

I can almost hear her say once again, “Il faut, il faut!” “One must always do better!” (Ludwig Binder)

Josephine with her benefactors, Prince Rainier and Princess Grace of Monaco. (Robert de Hoe, courtesy Photo Archive of S.A.S., the Prince of Monaco)

Escorting “Maman” backstage at the Pimm’s Club, my discotheque in Berlin, 1970. (Erika Rabau)

Au revoir, but not adieu! At La Madeleine, France mourns—but Josephine is still the Queen of Paris. (Above: Pellepam—SIPA Press; right: UPI)