Experience

Kate Kaul

“Experience” is built of two compounded prepositional prefixes. Its “ex” has a range of uses, applying to space (“out of,” “from”), time (“immediately after,” “since”), cause (“by reason of”), transition (“from being”), and means (“by means of”); it also distinguishes a part from a whole (“out of,” “from among,” “made of”) (Traupman 1979). “Per” is “through,” in the multiple senses of space (“through,” “along”), time (“through,” “during”), agency (“through,” “by means of”), means (“through,” “by”) and—anticipating the claims-making function, the legal uses of “experience”—in oath (“by”) (Traupman 1979).

More specifically, “experience” comes from Latin’s “experire” (“to try,” “to put to the test”) and overlaps in early usages with “experiment,” which shares the same origin. In this overlapping usage, “experience” was a testing-out, in the sense of “proof by actual trial.” The Oxford English Dictionary tells us that this sense has passed into “the observation of facts or events, considered as a source of knowledge,” but this learning by observation is difficult to separate from “experience” in another sense, describing “an event by which one is affected.” Finally, “experience” is also the “knowledge resulting from actual observation or from what one has undergone.” This etymology points to an interesting shift in the relationship between the subject and the world; in “experience” as experiment, the subject tests out a possibility and learns from observation—out of, and through, a trial, a testing, an observed event. Later (and still now), it is the subject and not the world outside that undergoes events, who goes through and emerges out of them, who is tested, changed. The subject observes not only the outside world, but also herself.

“Experience” thus simultaneously presents a claim to knowledge and a refusal of knowledge; its radical possibility lies in our ability to take this simultaneity seriously. In the March 25, 1978 entry of her Cancer Journals, Audre Lorde writes: “The idea of knowing, rather than believing, trusting, or even understanding, has always been considered heretical. But I would willingly pay whatever price in pain was needed, to savor the weight of completion; to be utterly filled, not with conviction nor with faith, but with experience—knowledge, direct and different from all other certainties” (1980, 24).

To claim “experience” is to claim knowledge and authority based on imminence and immersion, on identity and life lessons, rather than on expertise; however, it is also—as Lorde demands—to claim knowledge that moves from these immediacies, these events, into an awareness based on reflection and return, a knowledge that can only be collective. The “belief,” “trusting,” and “understanding” that Lorde opposes to “knowing” have often been considered heretical in an epistemology that opposes feelings to truth. It is “experience” as knowledge, at the end of Lorde’s statement, which brings them together. Lorde’s title, “Breast Cancer: A Black Feminist Lesbian Experience,” asserts that experience can be both individual (“A”) and collective (“Black,” “Feminist,” “Lesbian”). Lorde’s claim to experience as knowing brings an experience of breast cancer into Black, feminist, lesbian knowing; at the same time, it sets Black, feminist, lesbian knowing into a long, troubled, tradition of knowing and experience. The heresy lies not so much in Lorde’s knowing through experience as in her bringing knowing, believing, trusting, and “even understanding” together.

In his Keywords entry on “experience,” Raymond Williams presents the word’s dual structure, its insistence on both immediacy and reflection. Williams distinguishes between “experience past” (lessons) and “experience present” (full and active awareness); the two are, he suggests, “radically different, yet there is nevertheless a link between them, in some of the kinds of action and consciousness which they both oppose” (1976, 127). At its most serious, “experience past” includes those processes of consideration, reflection, and analysis that the most extreme uses of “experience present” as unquestionable authenticity and immediacy exclude (128). “Experience past” (lessons) suggests that “experience present” (immediacy) constantly offers to the present the possibility of knowledge that has traditionally been understood as available through “experience past.” As Williams suggests, there is a dialectic relationship between these two senses of experience. The etymology he offers demonstrates not a replacement of one sense by the other but, instead, a historical ambivalence in which the careful consideration of what has happened and a physical immediacy that defies consideration are set against each other.

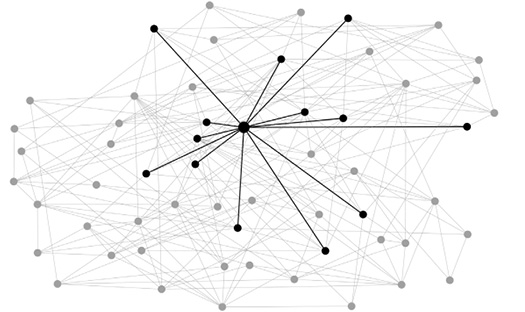

Lorde is not alone in pointing out that writing, or expression, is the work that turns the things we live through into the knowledge we share with others—a knowledge she identifies with experience. Michel Foucault’s (1991) notion of the “experience-book” recognizes that the production of knowledge from experience involves many more of us, and asks more of us, than any writer, reader, or actor, can anticipate. The experience-work that moves us from surviving events to thinking through them, from individual encounters to collective response, is discursive. As discourse, what has been said and what can be said about (and through) “experience” depends on relations of power and knowledge (Foucault 1972). Bringing knowledge, language, and power together, “experience” moves different kinds of subjects in and out of recognition and intelligibility.

At the first Disability Studies conference I ever attended, there was heated debate over whether able-bodied people should be working in Disability Studies. “I don’t care who does this work, as long as they have the disability experience,” a woman behind me said as the conference hallway around us filled with blind people, Deaf people, people with invisible disabilities, and (presumably) people without any. Standing in a crowd of unfamiliar bodies, I was thrown off balance by this statement. What was “the disability experience”? What was it in that moment? According to Mikhail Bakhtin, “there is no experience outside its embodiment in signs. It is not experience that organizes expression, but, to the contrary, expression that organizes experience, that, for the first time, gives it its form and determines its direction… Outside material expression, no experience. More, expression precedes experience; it is its cradle” (quoted in Todorov 1981, 43).

The “disability experience” to which the speaker referred was a claim to authenticity, to life lessons, to the immediacy of living with, or near, disabled bodies. But it was not only this; in offering me a term—a sign—for something I had not thought about, it asked me to pay attention to two questions: what was “the” disability experience? And what was this work that “we” needed to do?

Historian Joan Scott suggests approaching—rather than appealing to—experience and, instead of embracing it uncritically, “focusing on processes of identity production, insisting on the discursive nature of ‘experience’ and on the politics of its construction. Experience is at once always already an interpretation and something that needs to be interpreted” (1992, 797). This focus, this critical attention, is part of experience itself. And, in the discourse of “experience,” no appeal to experience can be entirely reduced to “experience present” or “experience past”; each extends into the other.

Slogans like “the personal is political” and “nothing about us without us” present the urgency of appeals to “experience” and reveal the extent to which we need one another to understand and assert ourselves as individual subjects. In the context of disability rights activism, “nothing about us without us” makes the crucial claim that there is an “us,” that “we” exist and have a collective opinion—or, at least, that we are a collective that includes opinions. “Nothing about us without us” points to the dual function of experience: living-through and making knowledge from. It also reminds us that the relationship between the personal and the political is corporeal—we live it, think it, experience it, through and in our bodies—and we experience not only as individuals but always in a social context (Kruks 2001, 149). Activists use “experience” as a way of understanding identity—sameness, collectivity—but the claims to experience that ground identity politics have taken many different forms. “What counts as experience is neither self-evident nor straightforward,” Scott argues; “it is always contested, and always therefore political” (1992, 797). Whose experience counts (and, as a result, who counts) is also always contested, always political.

In Lorde’s frame, the work of experience is collective, epistemological action; it produces knowledge. Violence can be felt individually, but oppression—like epistemology—is collective. Experience emphasizes perspective; the sense-making of “experience past” relies on the testimony (the account) of someone to whom things are happening, or have happened, in some “experience present.” This extension from the collective to the individual, and from the individual to the collective, is the only way “experience past” can work and the only way “experience present” can mean. Who is that collective? Whether it is the Black feminist lesbians to whom Lorde extends her identification, the women she addresses in her memoir, or the reader she cannot anticipate, the collective is not defined in advance of or in anticipation of meaning-making; instead, it arises through it. For Bakhtin, the “utterance” is only recognizable when it ends with a response. In listening, recognizing, responding, we declare ourselves a “we” capable of experience.

For Giorgio Agamben (1993), along with language, “experience” marks the move from infancy to history; similarly, for William Blake, “experience” is the end of innocence (Jay 2004, 1). As in Williams’ formulation, these frameworks remind us that nothing yells “time” quite like experience. As imminence, “experience” is a being-in-the-present moment; however, experience is also the move from infancy and innocence into language and knowledge. Experience represents the impossibility we live: only ever in one moment, always aware of others, in a knowing that embodies this tension and is only possible through our awareness of time. Experience joins the urgency of the immediate to the lessons of the past, enabling our imagination of the future—and it is only this imagination that makes action possible in the present.

Like “experience,” “radical” has a dramatic, dual, relationship to time. In its 21-page entry, the OED connects “radical” securely to “root”: “relating to a root,” “fundamental,” “inherent.” A radical medical treatment, then, is not necessarily a drastic one but one that is directed at the root cause of a disease. In connection to change or action, “radical” means: “going to the root or origin; touching upon or affecting what is essential and fundamental; thorough, far-reaching.” Like “experience,” then, “radical” reaches both backward and forward; radical action and radical knowing identifies what is fundamental to determine what must be changed. Like “radical,” “experience” calls for a close attention to change, to authenticity, and to knowledge. It summarizes the work involved in bringing belief, understanding, and knowing together. Each present moment is a crystallization of this complicated path.

Claims to experience are claims to identity, knowledge, and community, but the notions of identity they appeal to are necessarily provisional, imperfect, and contested. Experience makes subjects but it also makes collectives—even if these are better described in terms of “allegiance” (Joyce 1987, 382) than of sameness or familiarity. Arguments that a transgender woman’s experience is not and does not represent women’s experience, and that a celebrity transgender transition is not and does not represent transgender experience, reenact the old drama of experience in which individual and collective can never neatly align. Despite fierce debates over whose experience counts (and who is counting), “experience” presents a way to value difference rather than to insist on sameness. If, as Sonia Kruks suggests, feminists orient toward the vast social differences between women rather than foregrounding “minimal commonalities,” then focusing on experience may be a way toward “solidarity” rather than similarity (2001, 152).

An appeal to “experience” is always an attempt to connect individual experience to something collective—and it involves collision and failure as much as it does connection. Claims to experience may be imperfect; however, they are part of how we make sense of ourselves and one another, of how we make ourselves—and are made—in the world. We no longer think of “experience” as the experiment that a subject carries out on the world, learning from the results; in the twenty-first century, “experience” is something in which we are all entangled together.

See also: Accountability; Agency; Authority; Bodies; Class; Community; Friend; History; Misogyny; Oppression; Politics; Queer; Space