It was the breakthrough Phil Woosnam had longed for. Hindered by the lack of any meaningful television coverage of his league and with only the Cosmos gaining any kind of international recognition, the NASL was at a pivotal point in its short history.

With Pelé’s legacy in grave danger of coming to nothing, what the NASL needed now, more than ever, was a network TV deal to take its product into America’s living rooms and to those armchair fans who had yet to sample soccer. Without one, the Cosmos could go on signing the biggest and best names in the world game, but whether it would have anyone to play against would be entirely another matter.

In mid-November, Woosnam proudly announced that the NASL had signed a two-year deal with ABC television that guaranteed nine live games, including the Soccer Bowl, during the 1979 and 1980 seasons. While Woosnam had wanted more games and more money, it was, at the very least, a huge leap forward for the league and for soccer in the States. Television was crucial,’ says Woosnam. ‘It had always been a thorn in our side and when we finally signed a deal with ABC it looked like we were getting somewhere.’

For ABC, it seemed to be a gamble worth taking. While there had been some limited coverage of World Cup tournaments in the States, there had been little programing devoted to domestic soccer. For the most part, the big networks had shied away, largely because of the difficulties of screening it. While established sports like baseball and American football were awash with myriad opportunities for commercials, soccer lacked natural breaks, not to mention the kind of intervals that would lend themselves to statistical analysis or interesting facts—something that sports fans in the States adored. Indeed, when CBS had tried to screen games in the old National Professional Soccer League in 1967, one referee, Peter Rhodes, admitted that of the twenty-one free kicks he called in the game between Toronto and Pittsburgh, eleven were only awarded so commercial breaks could be shoehorned into the program. He was even seen to hold one prostrate player down just so a commercial break could be completed.

There was also the problem of soccer’s low scores. While the NASL had introduced the shoot-out so that no league game could end in a tie, the notion that a team could win a game by just one goal to nil was at odds with American sports fans’ expectations. Asking viewers to give two hours of their weekend in return for a single goal was always going to make it hard to attract new fans to the game.

But with the upsurge in attendances and the perceptible rise in the game’s profile, it appeared that the time was right for ABC to try its hand at soccer. Jim Spence was senior vice president of ABC Sports at the time. ‘We had hopes that it [the NASL] was going to be the next big thing,’ he explains. ‘The North American Soccer League had shown some real progress [and] the New York Cosmos were very popular . . . The league seemed like it had a real future so we wanted to get involved.’

Needing an authoritative, charismatic presence to front their coverage, ABC turned to Jim McKay, the widely respected host of their Wide World of Sports program and a huge fan of the game. ‘He loved soccer and he really had great hopes on a personal level that it would be successful,’ adds Spence.

ABC also enlisted Paul Gardner as a color commentator. Gardner was a Brit based in Manhattan. He had written an acclaimed history of soccer called The Simplest Game and was known as much for his passion for the sport as for his knowledge. ‘I don’t think anyone thought they were going to get a lot of money from TV because you only get that when the ratings come in,’ he says, ‘but in terms of publicity and in terms of joining the big guys [like] the NFL and the NBA … it was very important to the league at that stage.’

While the NASL and ABC were delighted with the agreement, not everyone was convinced that the deal would prove beneficial to the long-term prosperity of the league. Ed Bleier was the chairman of the NASL’s Television Committee. ‘I had a very different view of our television potential than the other team and club members,’ he recalls. ‘They wanted an instant network contract and I said we will go on television and fail, then they will blame soccer … I wanted us on anthology shows, like the Wide World of Sports with standings, players, saves, goals, player of the week to build all the intrinsics of the sport and only put the championship game on television. I was overruled. I got out voted.’

The network TV deal would bring a new sense of purpose to the existing franchises in the NASL and encourage a glut of new signings to enter the fray. Johan Cruyff aside, the most prominent transfer was that which took the prolific West German striker Gerd Müller to the Fort Lauderdale Strikers. Nicknamed ‘Der Bomber’, Müller was, unquestionably, the most lethal striker of his generation. In his sixty-two appearances for West Germany he recorded an incredible sixty-eight goals, while in the World Cup Finals of 1970 and 1974 he scored a record fourteen in just thirteen games, including the winner in the 1974 final against the Netherlands.

While the rest of the NASL franchises were bolstering their squads, confident that national television exposure would lead to healthier crowds and increased revenue, the Cosmos too had been scouring the world for the best talent that Steve Ross could afford. Normally, this would have involved the coach earmarking those players he felt could improve his team, taking the names to the board and allowing them to commence negotiations. Now, though, Eddie Firmani found himself subject to the whim of the Warner management, and had to sit by as a steady stream of acquisitions, such as the Brazilian defender Francisco Marinho, the Dutchman Wim Rijsbergen and the Iranian Andranik Eskandarian, arrived at the club, all seemingly without the coach’s blessing.

Firmani’s crime, it appeared, was to have substituted Giorgio Chinaglia in the previous season, a decision that had not only damaged the relationship between the two men but suggested to the board that Firmani harbored opinions of his own. The one thing Warner didn’t want in such an influential position, it seemed, was a free thinking individual.

They could have no quarrel, though, with his record as coach. In his two seasons at the club, the Cosmos had won unprecedented back-to-back Soccer Bowls, and he had lost only a handful of games. He had taken a team who had lost its most charismatic, most accomplished player and made them an even stronger proposition.

In Francisco Marinho, the Cosmos, and not Firmani, had signed an undeniably talented player but one who could and would test the resolve of the most hardened coach. With a thatch of blond hair, an impossible tan and confidence that knew no bounds, Marinho was also the kind of player who got on Giorgio Chinaglia’s nerves. In training, he would routinely take potshots at goal from distances and angles not even Pelé would have considered, sending the ball yards over the crossbar and high into the upper tier of the stands. With his shooting threatening everything but the goal, he was soon nicknamed ‘Mezzaninho’ by his teammates.

That said, Marinho was a Cosmos player through and through. Gifted on the field, he soon acclimatized to the rich social scene available off it. Indeed, within weeks of signing, he would even be suspended for breaking Eddie Firmani’s curfew. On the eve of one home fixture, the Brazilian was caught in bed with two women at the Hasbrouk Heights Hilton in New Jersey when he should have been resting before the game.

Eddie Firmani’s decision to suspend Marinho rankled with the Erteguns and soon after, when Firmani also dropped the goalkeeper—their goalkeeper—Erol Yasin, it seemed as though the coach had as good as signed his own resignation letter.

Certainly, Giorgio Chinaglia no longer had any time for the coach, their relationship now nothing more than perfunctory. It seemed that if you wronged Chinaglia you stayed wronged. Yet the Italian was still held in high regard by the club, if not by all of the Cosmos fans. For the game against Tulsa Roughnecks on May 20, the Cosmos board declared that it would be ‘Giorgio Chinaglia Day’, in recognition of his extraordinary goal-scoring record with the organization. Over 46,000 people turned up for the game and were entertained by a succession of Chinaglia’s friends and admirers who took to the field to deliver eulogies to the Italian striker. Clive Toye couldn’t make it.

While the pre-game entertainment had been received warmly, Chinaglia then found himself being booed by sections of the home crowd during the game itself. The Newsday columnist Johnette Howard once wrote that the New York sports fan ‘will boo his own mama if she burns the breakfast toast’. She wasn’t wrong. Despite Chinaglia’s scoring twice in a 3–1 Cosmos win, the crowd had taken the opportunity of his special day to voice their displeasure at what they perceived as his constant scheming behind the scenes. ‘There were many occasions when he was roundly booed by the fans,’ recalls Bob Iarusci. ‘I think they just wanted him to be a player and nothing more.’

Not that he cared. As the archetypal pantomime villain, he reveled in the attention. ‘It was because of my interference with the team,’ he concludes. ‘Some people they used to like I got rid of.’

One of those people was Eddie Firmani. When the Cosmos sacked him on June 1, 1979, it cited the inability of Firmani and the board of directors to agree on the direction of the club. The same line had been peddled for Clive Toye’s resignation and echoed the commonly cited reason for rock bands splitting: ‘musical differences’.

Later, Ahmet Ertegun attempted to explain Firmani’s dismissal. ‘Look,’ he told the press. ‘I think Eddie Firmani’s a terrific human being, and I think he’s probably relieved that this is over. There was dissension in our locker room. I understand that we’re probably going to always have dissension. Coaching the Cosmos is one of the hardest jobs in the world. We’ve got a lot of great players. We’ve also got a lot of personalities, you know, egos.’

As Eddie Firmani had discovered to his cost, not all of those egos lived in the locker room. Quizzed about his sacking, he remained tight-lipped, saying, ‘I enjoyed my experience with Cosmos. I mean I enjoyed dealing with the players and with the public. It was the other facets I didn’t enjoy so much that I don’t wish to speak of.’

When Giorgio Chinaglia finally spoke on the subject, there was a discernible lack of sympathy for Firmani. ‘It’s all over now,’ he said. ‘The old coach is gone, the new coach is here and we’re trying to play the best we can. Why talk about something when it’s history?’

In the wake of Firmani’s departure, the New York newspapers all ran pieces on the club’s handling of the situation, with most expressing incredulity that Firmani had been sacked. It didn’t end there. Throughout the NASL, the issue provoked a variety of opinions, ranging from bewilderment to resignation. Former Cosmos coach Gordon Bradley, now coach for the Washington Diplomats (and therefore free to say what he liked about the Cosmos), maintained the decision was typical of a club where wrong often passed for right, black could be mistaken for white and where the coach was coach in name only. ‘One thing that is difficult is that men like Eddie and I grew up with a system, a system which allowed the coaches to choose their teams and then put those teams on the field as they saw fit. That way, if a coach chooses the right players and wins, he gets the credit. If not, he takes the blame, period. Here, though, especially with the Cosmos, a coach feels like he doesn’t control his own destiny.’

Even the younger players in the squad were tiring of the incessant squabbling. ‘You learn to live with the atmosphere,’ said Gary Etherington, the twenty-one-year-old striker from North Virginia. ‘I’m not saying that it’s good or bad, but you kind of get used to it—it’s a part of your life day in and day out.’

The man charged with taking the Cosmos on to a hat trick of Soccer Bowls was Ray Klivecka. A former United States youth team coach, Klivecka was Firmani’s assistant and had been asked to shoulder the responsibility for the remainder of the season. Within four days of his appointment, though, Pelé’s old adviser, Professor Julio Mazzei, would be appointed as the interim technical director of the club, a move which effectively put Ray Klivecka straight back in his old position of assistant coach. ‘We have great confidence in Professor Mazzei,’ said an official club statement, ‘because of all his years of experience in soccer and the respect he enjoys throughout the soccer world, both on and off the field.’

The fallout from Eddie Firmani’s sacking overshadowed the buildup to one of the most intriguing games that the Cosmos would play. With a 10–2 record behind it in the league, it had shoehorned an exhibition game against the reigning world champions, Argentina, into its schedule. It would prove to be a fascinating test of the team, and, according to press rumors, an opportunity for Ahmet Ertegun to sound out the Argentinian coach, César Luis Menotti, about taking over the Cosmos at the end of the season. Having taken the Argentinian team to a World Cup victory in 1978, the chain-smoking Menotti (who had also played for the New York Generals in the late 1960s) certainly met Ertegun’s criteria for a new coach. The Cosmos president had told the press that he wanted ‘a top, world-renowned coach, who can give this team the kind of spirit and evenness of play we’re looking for’.

When kickoff arrived, it was difficult to envisage anything other than a comprehensive Argentinian victory. After all, the visitors were the team that had out played an outstanding Dutch side in the World Cup final and were considered to be at the height of their powers. In addition, the opposition could count on some typically slapdash preparations from the Cosmos. In short, there were all the ingredients for a mauling unlike anything the Cosmos would ever encounter in the NASL.

As it turned out, it was the Cosmos that surprised everyone. Performing at a level above and beyond most people’s expectations, it more than held their own against the world champions (who also fielded a seventeen-year-old called Diego Maradona in their lineup) and only lost when the visiting captain, Daniel Passarella, scored a controversial winner with two minutes remaining.

While still a defeat, the result was nevertheless a testament to the huge strides the Cosmos had made, and though the reaction of the 70,000 fans in Giants Stadium that night spoke volumes for the effort the team had put in, it was the response of the Argentinian coach that showed that the team was becoming a genuine force in the world game. Having kept his team in the locker room for over forty minutes after the final whistle, Menotti eventually appeared before the media and, through an interpreter, blamed the artificial turf for his team’s less than convincing victory. ‘We had to change our shoes at halftime because of the field. It gave us serious problems. I don’t think you can say the Cosmos have a very good team until they learn to play in other places besides here, on this field.’

It was an ungracious reaction that did little to engage his American suitors. When he refused to entertain the idea of a money-spinning rematch, the possibility of Menotti taking over at the Cosmos withered on the vine.

If proof were needed of the superfluous nature of the position of Cosmos coach it materialized less than two weeks after Eddie Firmani’s exit, when, despite the upheaval in the locker room and the uncertainty over the position of coach, the Cosmos signed the Dutch midfielder Johan Neeskens on a five-year, $1.6 million contract. ‘We had to choose if we wanted a Neeskens type of player or a Cruyff type,’ explained the Cosmos president, Ahmet Ertegun. ‘Cruyff is thirty-two, and likes to run the show. We have enough of those.’

If previous coaches had issues with some of the signings that arrived at the club, none of them would have questioned the wisdom of buying a player of Neeskens’s stature. At twenty-eight, he was in the prime of his career and boasted the kind of international experience and reputation for which any coach at any club would have paid a premium. He would also prove to be a more than capable deputy for the injured Franz Beckenbauer. ‘Our ground was Astroturf and at least half of the grounds in the league were Astroturf and Johan had no fear of doing slide tackles,’ says Steve Hunt. ‘He would rip himself to pieces but next time he would do it again, you know. [He was] a very hard man and just crazy, an absolute lunatic. Good to have on your team though.’

If the size of the Cosmos organization had changed beyond recognition—the squad alone now had thirty players on it—the camaraderie was, for the most part, as strong as ever, even if the oc-casional spat, suspension or sacking threatened to spoil the party. Shep Messing, their former goalkeeper, once described life on the road with the Cosmos as being ‘like a bad Fellini movie’. He had a point. If Bobby Smith and Giorgio Chinaglia weren’t arguing the toss over the relative merits of communism and capitalism, then Steve Marshall was dancing up and down the aisle of the plane (or team bus) like a drunken uncle at Christmas, or Francisco Marinho was roaming from hotel bed to hotel bed on his own kind of workout.

It was all but impossible not to join in and the new recruit Johan Neeskens quickly adapted to the Cosmos way of life. On one flight to an away fixture, the Dutchman decided to liven up proceedings by making the journey in drag. ‘He had the lipstick and the dress on and then he stuck golf balls in his shirt. It was originally funny, but then it became uncomfortable. He stayed in drag the whole damn flight,’ remembers Phil Mushnick of the New York Post.

Even Franz Beckenbauer, the epitome of Teutonic detachment, had long since ditched any pretensions he had to remain aloof from the craziness of the Cosmos roadshow. Now, after two years in the Big Apple, he was a man very much at ease. He could walk through Central Park without being mobbed, or go for dinner and actually enjoy it and, on the advice of his friend Shep Messing, he had even discarded his hair dryer in favor of letting his hair dry naturally. Once, when Beckenbauer was dining with Ahmet Ertegun at Elaine’s restaurant on Second Avenue, he noticed the film director Woody Allen at a neighboring table and mentioned to Ertegun that he would like to meet him. As the man who knew everyone, Ertegun took Beckenbauer by the hand and led him to Allen’s table. ‘Before I could say anything,’ recalls Ertegun, ‘Woody Allen turns around and says “My God, Franz Beckenbauer!’”

Certainly, the Cosmos was a team brought together by a common purpose, not to traverse the States and convince the nation that it was right about soccer and America was wrong, but to secure handsome salaries, a first-class lifestyle and the opportunity to wring every last drop of fun out of New York City. In doing so, however, a rare team spirit and solidarity emerged and found a spiritual home in the locker room at Giants Stadium. ‘I miss the locker room always. I’m married [and have a] family, and all that stuff is beautiful, but being part of a locker room, and that team,’ sighs Bobby Smith, ‘you don’t replace that kind of an experience, you really don’t. That locker room is our place, and it’s beautiful, you know.’

Franz Beckenbauer agrees. ‘In the New York Cosmos we had fourteen different nationalities,’ he explains. ‘Everybody was a stranger in the city and that’s what kept the team together. We had much more spirit than other teams I played [for].’

As the club’s car supplier, the Brooklyn car dealer Joe Manfredi took it upon himself to ensure that the players never wanted for anything. He would routinely pick up the tab for team blowouts, scout towns for the best venues for post-game parties and hand over the keys to up to forty new cars to the players, management and front desk each season. ‘When we went out and you would reach for your wallet it was like an insult to Joe,’ explains Steve Marshall, ‘because he felt like he wanted to be part of the family and unfortunately he felt the only way he could do that was to buy every drink.’

Surely nobody could begrudge Manfredi the good times. Having supported the club through the lean times Manfredi was finally hitching a ride with a team that was every bit as famous, in the major conurbations at least, as the Mets, the Giants or the Knicks. Indeed, Manfredi was now such a fundamental part of the Cosmos family that on match days he would travel with the squad on the bus (he called it the ‘happy tank’), have use of his own locker in the locker room and then sit next to the substitutes in the dugout. Such was Manfredi’s devotion to the Cosmos cause that he even missed the births of his children to be on the road with the Cosmos. ‘I never saw them being born to be honest with you,’ he admits. ‘I’m not proud to say that, but I tell you being with the Cosmos—I think it was the right thing to do.’

Steve Marshall spent many a drunken evening with Joe Manfredi but while Manfredi maintains that life on the road was nothing but ‘clean fun’, Marshall remembers it differently. ‘Joe would always want to go out,’ he laughs. ‘He liked the hotel bars but he liked to venture out to clubs … he was quite the party animal.’

At the end of the regular season, the Cosmos boasted a 246 record, and having retained their National Conference Eastern Division title with a total of 216 points, they had also broken their record for the number of points gained. That they were heading, inexorably, towards a third consecutive Soccer Bowl triumph seemed indisputable, especially after they breezed past Toronto in the opening game of the play-offs. While the Tulsa Roughnecks took the Cosmos to a minigame decider in the next round—a Chinaglia pair helping them through 3–1—it would be the game against the Vancouver Whitecaps that would go down as one of the greatest games ever witnessed in the NASL.

The Cosmos and Vancouver had history. All season, Tony Waiters’s Whitecaps had got the better of them, winning 4–1 at their own Empire Stadium in June and then winning again at Giants Stadium in July, 4–2.

The latter game had been a prickly affair. When tempers flared during the second half, Vancouver’s bear-like English goalkeeper, Phil Parkes, took the opportunity to offer Giorgio Chinaglia one of his choicest Anglo-Saxon insults. Rising to the bait, the Italian began throwing his weight around like a street brawler and the referee duly sent Chinaglia off.

Then, what had started out as a soccer match descended into farce. As the official brandished his red card, Chinaglia responded by ripping the card out of his hand, tearing it up in front of his face and then throwing the pieces to the ground. As he stormed off, the Cosmos fans began booing Parkes for his part in Chinaglia’s dismissal while Parkes, a player who took great delight in antagonizing the opposition, turned to face them and blew them kisses.

The two games against Vancouver (three, if you include the minigame) would have everything any soccer fan could ever want. There were suspensions and shoot-outs, heroes and heartache. There were flare-ups, disallowed goals, red cards and sheer exhaustion; Giorgio Chinaglia even barged the linesman.

Some three hours and forty minutes after the contest began it finally ended when the Cosmos’s Nelsi Morais, taking the final shot of the second shoot-out of the day, scored his goal. For once, however, it wasn’t the Cosmos that had won. According to the stadium clock, Morais’s shot had come one second after the five-second deadline. The Whitecaps went through to the Soccer Bowl.

After the game, the Cosmos locker room, so often a scene of celebration and superstar shoulder-rubbing remained closed as the postmortem began. As the media pack battled to get inside, one reporter demanded to know why they weren’t allowed in. As he pushed his way forward, Jay Emmett instructed a nearby security guard to ‘shut that door in his face’.

Later, Professor Julio Mazzei emerged from the gloom of the locker room and with a distinct lack of grace, poured scorn on the Whitecaps’ victory. ‘Vancouver won because the league wanted [the] team to win,’ he grumbled. ‘The officials were against us in the play-offs.’

The Cosmos’s glorious reign had ended, not in dignified defeat but in allegations and petty squabbling. Newsweek perhaps summed it up best when it suggested that the Cosmos had been ‘victims of their own arrogance’.

But while Vancouver’s victory (and their eventual triumph over Tampa in the 1979 Soccer Bowl itself) was a surprise, it at least demonstrated to the other franchises that the Cosmos could be toppled and gave the impression that a new breeze was blowing through the NASL. On a wider scale, however, opinion varied as to whether the failure of the Cosmos to extend its sequence of Soccer Bowl victories was a good thing for the NASL. Although some semblance of genuine competition had been reestablished in the league, there was still a feeling that despite the league’s protestations to the contrary, the Cosmos was still carrying the NASL and if their support began to wane then what future was there for the other franchises?

Hola! - The Cosmos team enjoy a preseason trip to Mexico. (Standing, left to right, men in hats unidentified): Len Renery, Roby Young, Randy Horton, Joe Fink, Werner Roth, Jerry Sularz. (Squatting, left to right): Siggy Stritzl, Charlie Martinelli, Everald Cummings, Malcolm Dawes, Ralph Wright. (Len Renery)

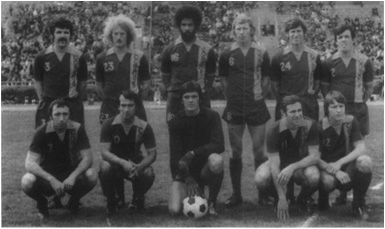

Team spirit - The 1974 Cosmos team line up at Randall’s Island. (Back row, left to right) Frank Donlavey, Len Renery, Randy Horton, Malcolm Dawes, Gordon Bradley, Barry Mahy. (Front row, left to right) Harold Jarman, Germy Rivera, Jerry Sularz, Jorge Siega, Joe Fink. (Len Renery)

The off-duty Cosmos - (left to right) Shep Messing, Giorgio Chinaglia, Werner Roth and Franz Beckenbauer. (Shep Messing)

Star spotting - Shep Messing and friend with Pelé and Eusebio (Shep Messing)

Flag day - Prior to his debut for the Cosmos, Pelé was joined on the pitch at Downing Stadium by Dallas’s Kyle Rote Jr. (Peter Robinson/EMPICS)

The New York Cosmos 1976 - (front row, left to right) Trainer Joel Rosenstein, Kurt Kuykendall, Bob Rigby, Terry Garbett, Jorge Siega, Pelé, Keith Eddy, Giorgio Chinaglia, Bob Smith, Werner Roth, Charlie Aitken, Edward Edgar, Shep Messing. (Back row, left to right) Head Coach Gordon Bradley, Frank Sauer, Barry Mahy, John Russo, Dave Clements, Charlie Mitchell, Ramón Mifflin, Nelsi Morais, Tony Field, Brian Tinnion, Brian Rowan, Mike Dillon, Tony Donlic, Assistant Coach Professor Julio Mazzei, Assistant Coach Joe Mallet. (Shep Messing)

Happy days - Franz Beckenbauer and Carlos Alberto share a joke. (George Tiedemann)

Access all areas - U.S. Secretary of State Henry Kissinger joins Franz Beckenbauer in the locker room. (George Tiedemann)

What’s up Doc? - Bugs Bunny wows the crowd at Giants Stadium. (George Tiedemann)

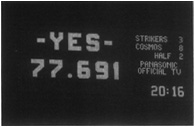

YES! - A record crowd for the 1977 play-off game against Fort Lauderdale Strikers. (George Tiedemann)

Smokin’ - The irrepressible Giorgio Chinaglia. (George Tiedemann)

Dutch master - Johan Cruyff meets the press after signing a short-term deal with the Cosmos. (George Tiedemann)

Dream ticket - Pelé’s farewell game against Santos at Giants Stadium was a sellout. (Shep Messing)

The greatest - Muhammad Ali joins Pelé on the pitch at his farewell game against Santos. “Now there are two of the greatest,” said Ali. (George Tiedemann)

The end - Pelé says his good-byes to Giants Stadium. (George Tiedemann)

Turning Japanese - After his last game in New York, Pelé and the Cosmos headed off on a tour of the Far East. (Shep Messing)

For all Phil Woosnam’s fervor—he once told ABC’s Jim Spence that the NASL would be bigger than the NFL within ten years—it was becoming painfully clear that soccer was never going to gain parity with baseball, basketball or football and the ratings for ABC’s live games certainly suggested that soccer was a game that had barely registered on the public’s radar. Locally, the ratings in those cities where soccer had strong franchises (New York, Washington, Tampa, etc.) had been respectable, but on a national basis the sport had bombed.

Of course, the problem had been compounded by the failure of the Cosmos to reach the Soccer Bowl, and its unexpected exit in the play-offs had dented not just the attendance at the final game—just 50,699 turned up, despite claims by Phil Woosnam that over 60,000 tickets had been sold—but had hit ABC’s overall ratings too. With a 2.7 rating (equivalent to approximately two million households) ABC was having difficulty finding sufficient advertising support. ‘In all candor,’ says Jim Spence, ‘our affiliated stations around the country were not enamored with a property that was generating those low ratings. Affiliates are selling their local spots and when you generate that kind of a rating it negatively impacts their sales effort.’

As the league sought to allay ABC’s fears that its investment was misplaced, it was clear that the scheduling of the nine live games had been a major contributing factor in the disappointingly low ratings. Showing live games on a Saturday afternoon (when fans and families the nation over had better things to do) had proved folly and the feeling that the NASL had snapped ABC’s hand off when the deal came along without really examining the detail was hard to avoid. ‘I think we sold our souls to national television, and we’ve gotten very little in return,’ said Jack Krumpe, the vice president of Madison Square Garden, owners of the Washington Diplomats. ‘Why should we agree to let them put games on at 2:30 p.m. on Saturday in the middle of the summer? That just isn’t worth a darn, it has no dramatic impact at all. Look at the ratings, they’ve been abysmal.’

There was also a steadfast public perception that, for all the razzmatazz, big-name players and million-dollar salaries, soccer was still a foreigners’ game. Moreover, while the Cosmos’s Rick Davis had blossomed into one of the league’s most consistent performers, he was still just one of only a handful of Americans who had the potential to make a name for himself. This noticeable absence of any homegrown heroes for the viewing public to follow not only quashed potential merchandising and advertising opportunities for the league but also served to reinforce the belief that soccer and Uncle Sam weren’t really meant for each other.

It wasn’t just the ratings. Despite a determined effort to present a soccer show every bit as professional as those they produced for the mainstream American sports, ABC had struggled to adjust to the demands of covering so unpopular a sport. Stymied by the need for commercial breaks they would often cut away to a break only to return to find that they had missed a major incident in the game, sometimes even a goal. Paul Gardner, however, maintains that given the constraints, ABC did an efficient job of televising the NASL. They were very, very professional those guys and they learned very quickly,’ he explains. Tf you look back at those telecasts I think you will see that the quality of them was excellent. . . considering that this was the first time that most of these guys had ever done soccer.’

If the ratings for the ABC games had been dismal, the attendances at Giants Stadium were also a cause for concern for Steve Ross and Warner. Although the average turnout for a Cosmos home game had only dropped by a little over 1,000 per game, the fall to 46,690 was the first decline since the move to the Meadowlands and, more worryingly, the first fall in attendances in five seasons.

There was more bad news on the horizon for the Cosmos. After a season in which he had managed just one substitute appearance for his team, the Cosmos captain Werner Roth had been forced to retire because of a knee injury. Of the scores of players that had ever pulled on the Cosmos shirt, it was Roth, the kid from Ridgewood, who had witnessed the incredible transformation of the soccer club. He had been there when only a few hundred people had bothered to show up. He had been there when they had to paint the field green. And he had been there when a monkey was the main attraction. Now, as his Cosmos drew crowds of fifty, sixty and seventy thousand, he found his playing career cut short by injury. Today, Roth looks back on his years with the club with affection, concluding that It was the best of times and it was the worst of times.’

Keen to repay his loyalty, the Cosmos board soon gave Roth a new role as director of youth development at the club, although he was also exploring other avenues. As well as trying to establish his own Soccer Safari training schools and commentating on the radio, Roth had also been offered a leading role in Escape to Victory, a John Huston film about a team of Allied POWs who take on the might of Nazi Germany in a soccer game. Pelé was already in it, as were Michael Caine and Sylvester Stallone, and the producer Freddie Fields wanted Roth as one of the Allied players, ‘until they found out that I could speak German and then all of a sudden I became the captain of the Germans.’