1 | Goethe in the Vienna Music Scene of his Era

Otto Biba

When works of Goethe first became known in Vienna, and when Goethe reception first began there, has not yet been thoroughly investigated. In 1776 a production of Erwin and Elmire marked the first performance of a play by Goethe on the stage of the Burg Theatre.1 This is to be seen as a sign of visible acknowledgement of the poet. At that time Vienna was experiencing, and had experienced, the Werther fashion.2 The Werther fever3, was, of course, weaker than in some parts of Germany: enthusiasm for the cult of feeling was also characteristic of Vienna of the 1770s. But the immediate production of parodies and travesties4 accompanied successful literary works of this kind in Vienna, and inhibited any drastic results of the Werther enthusiasm. In her memoires,5 the writer Caroline Pichler (1769-1843) relates:

Mich ließ der Werther, als Roman, kalt, so lebhaft mich die psychologische Wahrheit der Charaktere, die tiefe Kenntnis des menschlichen Herzens, die Naturschilderungen usw. anzogen.

Her mother had – as long as she considered her too impressionable and too immature – withheld from her two books that were widely read at the time: Goethe’s Werther and Wieland’s Agathon. At about the age of twenty or twenty-one she recounts how she read them:

[...] und sowohl meine Mutter als ich selbst mussten uns wundern, daß der Eindruck, welchen diese Werke auf mich machten, ganz dem erwarteten oder gefürchteten entgegengesetzt war. [...] Meine Phantasie, deren Aufregung man hauptsächlich gefürchtet hatte, blieb ruhig.6

Goethe’s world of feeling was familiar, but people were not carried away by it. For a relatively short time it was a fashion to follow, but one soon returned more or less to the terra firma of sober reality. Nothing illustrates this more clearly than Caroline Pichler’s judgement. Around 1790 her mother, almost certainly on the basis of her own experience, was afraid that Goethe’s Werther would cause her daughter an emotional upset. But this was not the case.

This is the background against which the first Goethe settings by Viennese composers are to be seen. They chose texts characterized by feeling and emotion, which, sufficiently supported by music, brought Goethe into the music repertoire as a poet belonging to the Emfindsamkeit era. It is not surprising, therefore, that in a song collection published in 1778 with works of the Court Pianist Joseph Anton Steffan (1726-1797)7 – the piano and music teacher of the children of the Imperial family – the first Goethe song contained8 in it is ‘Lotte auf Werthers Grab’. Thus the Werther fashion can also be traced in music and brought Goethe to the attention of composers. It is worth noting that the volume contains a setting of ‘Das Veilchen auf der Wiese by Gleim’, but in fact the poem, wrongly attributed to Johann Wilhelm Ludwig Gleim (1719-1803), is by Goethe. The Viennese were familiar with the text since 1776, as a song of Goethe’s heroine in Erwin und Elmire. In Part Three of this collection, which appeared in 1780, we again find a setting of the poem ‘Das Veilchen auf der Wiese’ by Karl Frieberth9, who had a career an opera singer, most notably under Joseph Haydn at the court of Prince Esterházy. He was conductor of choirs in important Viennese churches and was also known as a composer. As with all the other songs in this volume, the name of the poet is omitted.

In Goethe’s poem the violet wished to be plucked by a beloved young shepherdess and pressed to her bosom. But it is trodden on and so dies through her: ‘And if I die, at least I die through her, at her feet’, as we read at the end of the poem or song. That love finds fulfilment in death must have been a fascinating theme that was often taken up by composers of this time. It is not surprising therefore that in 1785 Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart went back to this Goethe text (KV 476): ‘Das Veilchen. Vom Göthe’ appears in his manuscript.10 The term ‘vom [von dem] Göthe’ shows that he was very familiar with the name Goethe, that he knew it intimately. Ulrich Konrad supposed that the basis for the composition was not a text edition of Erwin und Elmire, nor any other literary publication, but rather Frieberth’s setting which appeared in 1780.11 Fulfilment of love in death was a theme with which Mozart was often preoccupied, including the G minor aria of Pamina in Die Zauberflöte. His setting of Goethe’s ‘Veilchen’ can therefore be seen, on the one hand, as part of a chain of a musical tradition beginning in Vienna in 1778,12 and, on the other hand, as a central theme in his work.13

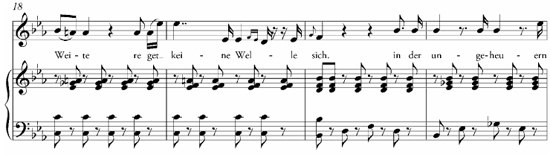

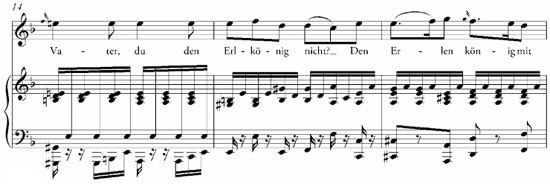

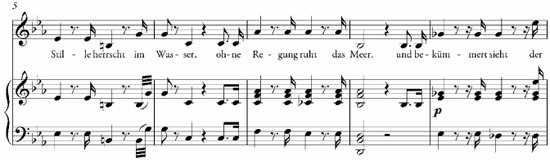

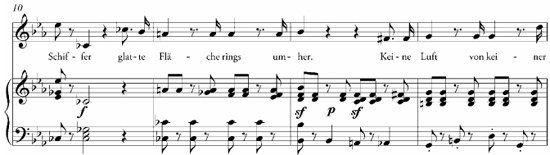

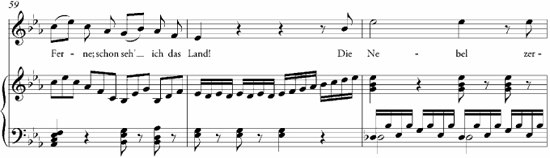

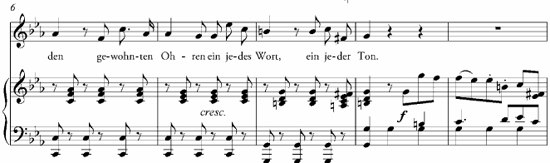

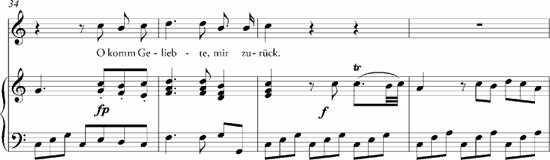

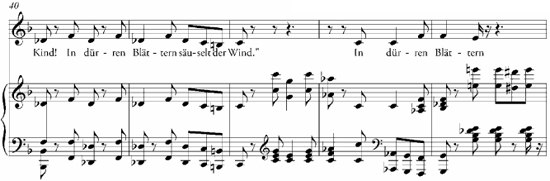

Example 1.1 Eberl, ‘Meeresstille, Glückliche Fahrt’

The sensibility of the Rococo period reflected in the theme of the lover’s yearning that leads to death (symbolized by an experience of nature), but also love and yearning for their own sake is evident in the four Goethe poems which Anton Eberl (1765-1807) chose for the six ‘Songs with piano accompaniment’14, op.23, published in 1804: ‘Nähe des Geliebten’, ‘Der Fischer’, ‘An die Entfernte’, ‘Meeresstille – Glückliche Fahrt’ (see example 1.1). Eberl was a piano teacher and composer in Vienna and several of his works were falsely circulated under Mozart’s name, which is understandable because to a large extent he followed Mozart’s musical idiom. It is worthy of special attention that in his Opus 23 he combined, for the first time, both Goethe poems – ‘Meeresstille’ und ‘Glückliche Fahrt’ – in one composition. Beethoven did the same in 1814/15 in his Opus 112, which, without Eberl as a precursor, would be unthinkable. With this combination Eberl was the first to see Goethe’s lyrical poetry under the aspect of musical drama. It was not until Franz Schubert that also Goethe’s dramatic ballads or his dramatic poems became interesting for Austrian composers. Indeed, Eberl’s Opus 23 was also a precursor for Franz Schubert: he, too, had set ‘Der Fischer’ und ‘Nähe des Geliebten’. At the same time, Eberl should not be seen as a direct model for Schubert – even if it is possible that Schubert knew Eberl’s settings – but rather as a precursor: Schubert belongs to an already different age, for he approaches the setting of these texts with completely new presuppositions and with different intentions. On 9 April 1804 Eberl sent Goethe a copy of his six songs, op.23.15 Characteristically, Goethe didn’t reply. But when on 30 January 1806 Josef Friedrich Freiherr von Retzer, with whom Goethe often corresponded on theatre business, sent Goethe a letter16 recommending that Eberl be warmly received in Weimar, Goethe responded. He was welcomed ‘at the Weimar Court both because of this recommendation and because of his talent, and I hope, when he left us, that he was not unhappy with the reception’, Goethe wrote to Freiherrr von Retzer17. This was a more or less official reception given to a travelling composer as was customary at courts interested in the arts. But that doesn’t mean that the visit gave rise to a profound discussion of song style and song composition, since it was not a private visit to Goethe.

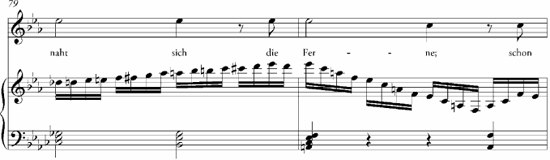

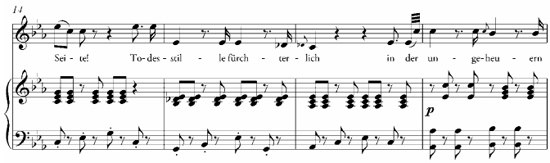

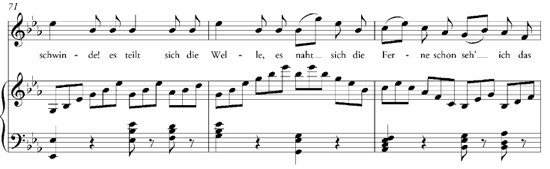

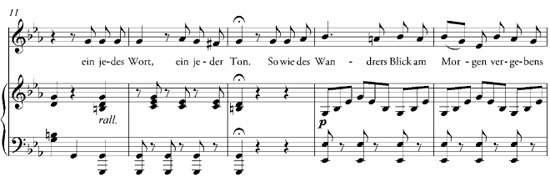

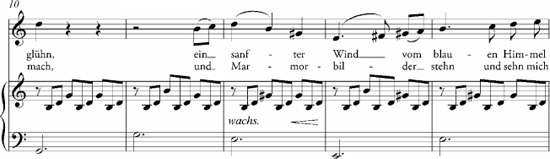

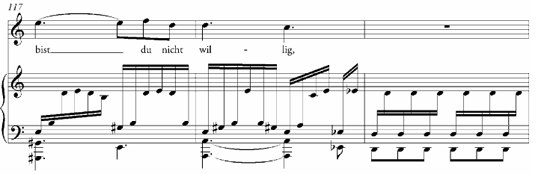

Example 1.2 Dietrichstein, ‘An die Entfernte’

In 1811 Graf Moriz von Dietrichstein (1775-1864) published sixteen settings of Goethe poems (two of them duets) in Vienna and dedicated them to the poet18. Quite apart from its musical quality, this edition is worthy of attention, firstly, because Dietrichstein called the poems he has chosen ‘Lieder’ and, secondly, because it is dedicated to Goethe. On 23 January 1811 the composer sent a copy of this edition to Goethe. He described himself as ‘enthused by your immortal Lieder’ – so, again, not poems, but Lieder – and ‘far removed from the illusion that I possess those excellent qualities which distinguish Herr Reichardt from all others’. It was clever to mention Reichardt, whom Goethe, as also later Carl Friedrich Zelter (1758-1832), so admired. For Reichardt (like Zelter) represented the Berlin Lieder school whose approach to song composition was fundamentally different from that in Vienna. Goethe was familiar with the Berlin School, whereas the song aesthetic of the Viennese was to a large extent foreign to him. Still, on 23 June 1811 Dietrichstein received an effusive thank-you letter from Goethe who was in Karlsbad. He assured Dietrichstein that the songs had given him much pleasure:

Ohne dass ich im Stande bin ein Kunsturtheil über jene Compositionen zu fällen, darf ich doch soviel sagen, dass mir sowohl ihre Anmut als eine gewisse Eigenheit des Charakters sehr viel Vergnügen gemacht hat. Es gibt zu interessanten Betrachtungen Anlaß, wenn man sieht, wie der Componist, indem er sich ein Lied zueignet [gemeint: aneignet] und es auf seine Weise belebt, der Poesie eine gewisse Vielseitigkeit ertheilt, die sie an und für sich gar nicht haben kann; woraus denn erhellt, dass etwas Einfaches und beschränkt scheinendes, wenn es nur wirksam ist, zu den manigfaltesten Productionen Anlaß geben kann. 19

Goethe’s very noteworthy and fundamental aesthetic comments reveal the extent to which he was inspired by Dietrichstein’s songs. He continues:

Sehr angenehm würde es mir seyn, diese Lieder von dem Componisten selbst oder in seiner Gegenwart vorgetragen zu hören, weil sie dadurch gewiß nur gewinnen können. Indessen haben unsere Sänger und Musiker sie mit viel Liebe und Aufmerksamkeit behandelt und mir dadurch manche vergnügte Stunde gemacht.20

In this letter Goethe mentions twice that he would like to get to know Dietrichstein personally.

Was it Dietrichstein’s social standing at the centre of a literary and musical circle in Vienna that drew such a detailed response from Goethe, or were there artistic reasons for the response? If one asks this question it is in the understanding that Dietrichstein was a very able composer and was acknowledged as such. He is not to be seen as a nobleman who, out of ambition or a misplaced enthusiasm, wanted to try his hand at composition. He had a perfect technical grasp of music and was in fact artistically gifted. He was also aesthetically educated and in these Lied settings, one can detect the subtle influence of Reichardt to please Goethe, to whom he wished to give a token of his devotion21. Goethe knew how to savour this. To explain it more simply: Dietrichstein’s Lieder are situated between Mozart and Schubert. They are far removed from Rococo sentiment, but the music is still the handmaid and not an equal partner of the text.

This aesthetic – which requires more of music than empathy with the sensibility of the text and is less interested in an additional or new interpretation of the text – is more advanced than Beethoven’s early Goethe Lieder: the ‘Mailied’, op.52/4, published in 1805 but of a much earlier date; ‘Aus Goethes Faust’, op.75/2; and the three songs from 1810, op.83. This is further corroborated by the fact that there seems to be no answer from Goethe when Beethoven sent him his cantata ‘Meeresstille und Glückliche Fahrt’, op.112. Here in Opus 112, which dates from the years 1814/15, Beethoven is striking out independently. The music rises with the aid of the text only to leave it behind, having achieved independence. It was the same (of course, to a much more modest degree) with Eberl’s setting of both of these poems, but also in the tone painting (‘der Wandrer bebt’ or ‘mit dumpfem Rauschen die Welle steigt’) of his ‘Nähe des Geliebten’. On the other hand, Eberl’s ‘An die Entfernte’ – a strophic song, in contrast to the two mentioned – is again in the tradition of Emfindsamkeit songs such as Beethoven’s ‘Mailied’ and equivalent settings of other early poems of Goethe.

Can we say that Eberl and Beethoven had to share the fate of hearing no response from Goethe to settings of this kind? For Beethoven it was the case that ‘I, too, have to remind you of myself’, as he wrote to Goethe on 8 February 1823, after he had received no reaction to his ‘Meeresstille und Glückliche Fahrt’. Beethoven wrote:

beide schienen mir ihres Kontrastes wegen sehr geeignet auch diesen durch Musick mittheilen zu können, wie lieb würde es mir seyn zu wissen, ob ich passend meine Harmonie mit der Ihrigen verbunden, auch Belehrung welche gleichsam als wahrheit zu betrachten, würde mir aüßerst willkommen seyn. 22

Even his assurance – ‘wie hoch würde ich eine allgemeine Anmerkung überhaupt über das komponiren oder in Musick sezen Ihrer Gedichte achten!’– did not help.23 What Beethoven had sent him did not belong to Goethe’s musical world. He avoided a long written discussion about it – as he had already done with Eberl – but he also wanted to avoid making a short negative reply. Whereas the Lieder compositions were made to be performed privately or in a semi-public musical salon, this particular work, with its cantata character, belonged to the few Viennese settings of Goethe texts to be performed in the concert hall. The first performance took place on 25 December 1815 in the Großer Redoutensaal. In February 1822 this work was published in Vienna by Sigmund Anton Steiner. It is well worth noting that the Leipzig composer Friedrich Rochlitz (1769-1842), who corresponded with Goethe and was appointed Court Councillor by the Grand Duke of Weimar, wrote a review24 in which he gave this work high praise. He was very attracted by this music which, with its tone painting, assumed an independent role – which, for Goethe, was too much of a good thing.

In contrast to Beethoven’s cantata and to Eberl’s settings, Dietrichstein’s Lieder corresponded to Goethe’s musical world. For us this is all the more remarkable because we are still captive to hero-worship. We busy ourselves with Goethe, Beethoven and Schubert but fail to see that we are better able to see the relationship between these three if we also take Eberl and Dietrichstein into account.

The same applies to the Goethe settings by Nikolaus Freiherrn von Krufft (1779-1818), a composer who today is completely forgotten, but whose Lieder and chamber music are as fine as any composed in Vienna at the beginning of the nineteenth century.

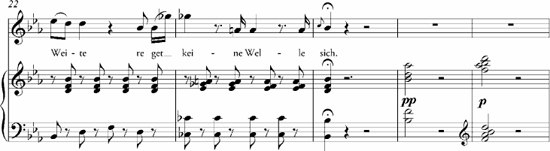

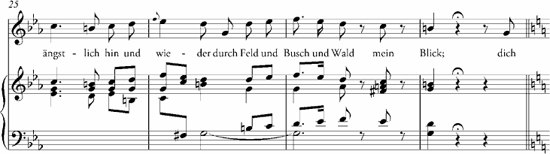

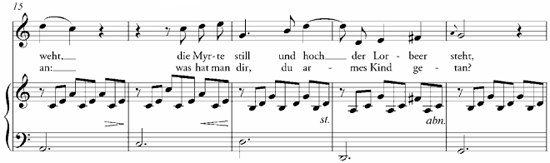

In 1812 he published 25 Lieder with piano accompaniment and a significant foreword dated February 1812:

Was die musikalische Behandlung dieser Texte betrifft, so hatte ich dabey einen dreyfachen Zweck vor Augen: Richtige Declamation in dem Geiste der Gedichte und mit Beziehung auf alle Strophen; möglichste Klarheit und Abründung der Melodie; unabhängige Clavier-Begleitung, so viel sich dieß mit der erforderlichen Unterstützung der Stimme vereinigen ließ. 25

These are strophic songs in which the music is neither subordinate nor dominant but plays a role equal with that of the text. They are, as the composer writes in the foreword:

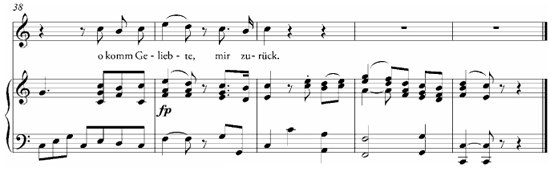

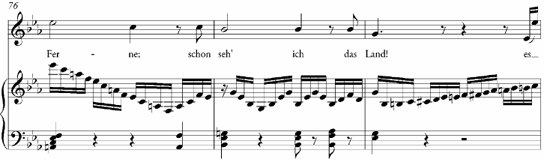

in den klassischen Dichtern Deutschlands geschöpft; bey einigen derselben, z.B. der Würde der Frauen, dem Troste in Thränen, dem Liede aus der Ferne, dem Liede aus Meisters Lehrjahren – traf ich in der Wahl mit sehr ausgezeichneten Tonsetzern zusammen; viele derselben wurden, so viel mir bekannt, noch nie componirt.26

Goethe is represented with three poems: Stylistically these Lieder are closer to Schubert’s than to Dietrichstein’s strophic Lieder. For anyone who wants to place Schubert’s Goethe settings in the proper context of the period, knowledge of these Lieder by Krufft is indispensable.

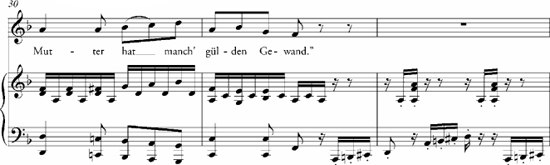

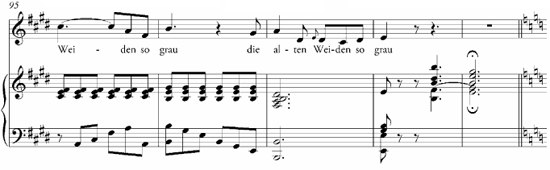

Example 1.3 Krufft, ‘Lied aus Wilhelm Meisters Lehrjahre’

Amongst the many Viennese composers who set Goethe texts to music, Johann Christoph Kienlen (1783-1829), originally from Bavaria, must also be highlighted, although he belonged to the Viennese musical world only in 1808, when he worked as theatre conductor in Pressburg (today Bratislava), and again from 1811 to 1816 when he was opera director and theatre conductor in Pressburg and Baden-Wien. Already in 1810, while working briefly in Munich, he published twelve Goethe Lieder in Leipzig.27

Kienlan’s setting of ‘Heidenröslein’, is, according to Max Friedländer28, ‘of all [settings of this text] the nearest to that of Schubert’. Around 1813/14 twenty of Kielen’s songs were published in Vienna29, seven of which have texts by Goethe: ‘Der Rattenfänger’, ‘Lied des Mephistopheles aus Faust’, ‘Ritter Curts Brautfahrt’, ‘Wechsel-Lied zum Tanze’, ‘Trost in Thränen’, ‘Wer kauft Liebesgötter’, ‘An Mignon’. His simple and unpretentious settings correspond exactly to the ideal of the Berlin Lieder School and thus to that of Goethe and his musical models, Reichardt and Zelter. It is no wonder that Goethe was interested in Kienlen, supported him and in 1815 recommended him for work in Frankfurt.30 The Goethe settings of Ignaz von Mosel (1772-1844) have a similar character, although we don’t know whether Goethe knew them. Like Kienlen, Mosel had, on the one hand, set texts with which we are familiar from Schubert, and, on the other hand, composed poems which we would never have expected to be set. For us the Goethe settings in the Lieder dedicated to Michael Vogl and published in 1820 are of particular interest. 31 Michael Vogl is known to us above all as a dedicatee and interpreter of Schubert songs. These settings of the poems ‘Sehnsucht. Aus dem Roman: Wilhelm Meisters Lehrjahre’, ‘Jägers Abendlied’, ‘Rastlose Liebe’ were also set by Schubert, though in a very different way.

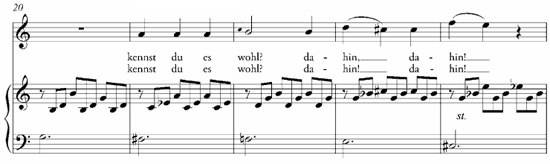

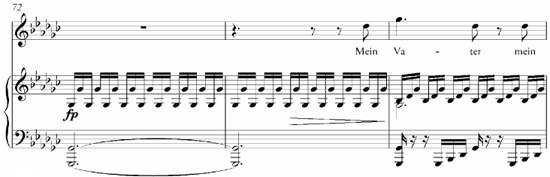

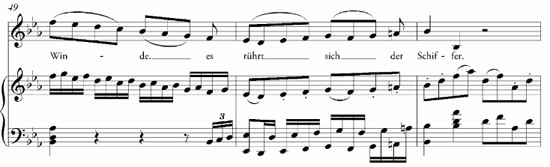

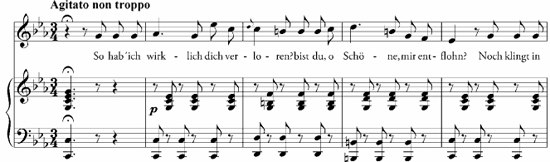

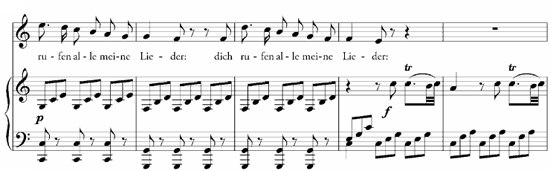

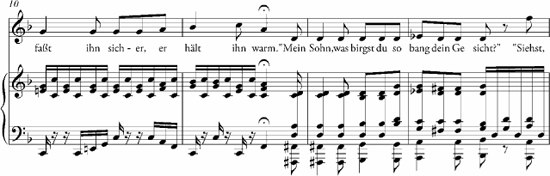

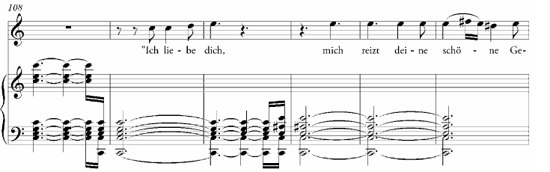

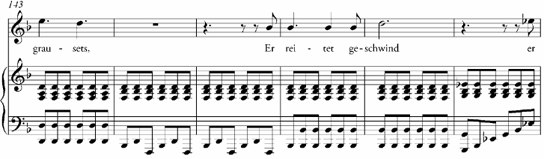

Out of this rich supply of material one final reference should be made to the Goethe settings of the Beethoven pupil, Carl Czerny (1791-1857), best known as a composer for piano. These settings were composed in the years 1810/11 and were not published, though this does not at all mean that they were not performed32: ‘Des Mädchens Klage’, ‘Das Geheimnis’ und ‘Der Erlkönig’ (see example 1.4). What the young composer produced leads us into a new era: his understanding of the Lied is that of Schubert. While he does not match Schubert’s achievement either in invention nor in artistic quality, he shares with him the ability to exhibit completely new possibilities for setting Goethe’s texts. They are, to begin with, through the tone painting in a completely independent piano part, not in line with Goethe’s aesthetic but are pointing to the future. If we were tracing lines of development, they would lead from Eberl via Czerny – and partly via Krufft – to Schubert.

Reference to these selected works of all the composers before, and contemporary with, Schubert is not only important for highlighting the strength of Goethe’s presence in the Viennese music scene of his time. These songs also show us that Schubert’s Goethe settings are to be seen in an historical perspective which reveal two aesthetic trends which needed to be described here. That Schubert trod a path that did not correspond to Goethe’s own aesthetic ideas about music and genre has often been discussed. But it is important to know that Schubert was not alone in this respect and was still less a pioneer. What was new in Schubert was that he set so many ballads and dramatic texts of Goethe which account for a higher percentage of his Goethe settings than with any other composer mentioned here. It is also important to remember that Goethe must have looked on the Schubert settings of his texts at least with good will, despite the fundamental aesthetic distance, for, according to the censorship laws which were tightened up as a result of the Congress of Vienna, the name of the dedicatee could only be put on the title page of a publication with his written permission. If Schubert dedicated his three Lieder op.19 ‘respectfully to the poet’33 there must have been a written permission from Goethe. It is a pity that it has been lost, but that it existed cannot be denied. It was not an acknowledgement by Goethe of Schubert’s Lieder style, but it was a proof of his respect for the composer.

Did the Viennese public make the aesthetic distinctions that Goethe did or could have done? Not likely, because it loved variety, newness – it sought new ideas, new conceptions and happily waited for something different, whatever it might be.

Example 1.4 Czerny, ‘Der Erlkönig’

Goethe’s presence on the Viennese music scene naturally affected the stage as well. In 1796, the director of the orchestra of the Vienna Court Theatre, Paul Wranitzky (1736-1808), asked Goethe whether he would entrust to him the setting of Part Two of the Zauberflöte that Goethe was working on. The poet thought very highly of Wranitzky’s Oberon, König der Elfen, and consented in principle. There were other reasons why the libretto remained a fragment and could not contribute to Goethe’s presence on the Viennese music scene.34 When the enthusiastic friend and patron of music, Joseph Franz Maximilian Fürst von Lobkowitz (1772-1816), advertised a richly endowed competition for opera libretti and asked Goethe to preside over the jury, Goethe declined, but he consented to look through the most deserving of the manuscripts that were to be sent to him. We don’t know what became of this, and there was no recommendation by Goethe of an opera libretto for Vienna. ‘May it please you to find time to come to Austria’, wrote Lobkowitz in this context. ‘I am convinced that you will find Vienna interesting in various ways, and Vienna won’t fail to appreciate its guest.’35 It is worth adding that Lobkowitz had earlier already been in contact with Goethe over musical issues concerning the Weimar Court Theatre.

In relation to musical drama, Goethe was present in Vienna for the first time in 1780. We can name here the following examples of operas with texts either by Goethe or in imitation of him. Usually it is stated, without any distinction, that the text is by Goethe. In the year 1780 the three-act opera Claudine von Villa Bella by Ignaz Beecke (1733-1803) had premiered in the Hofburgtheater; the opera remained on the programme and was also performed in the Kärntnertortheater. Franz Schubert’s Singspiel Claudine von Villa Bella, D 239, composed in 1815 and unfortunately partly lost, was not staged in a public theatre. There is some evidence that there was a private performance (at least of some numbers) in a Haustheater.36 Similarly it is a matter of regret that nothing came of the project of a setting of Claudine von Villa Bella by the Haydn pupil, Anton Polzelli (1763-1855), because Goethe gave advice for its composition.37 On the other hand, in 1830 Claudine von Villa Bella by Joseph Drechsler was performed. Scherz, List und Rache, a German opera with Goethe’s text and music by Peter von Winter, had its premiere in Vienna in 1784. In 1794 Goethe’s Singspiel Erwin und Elmire, published in 1788 (the previous year there was a revision of the drama which had been performed at the Wiener Burgtheater as early as 1776) with music by Josef Martin Ruprecht (1756-1800), was given its first performance in the Kärntnertortheater.

In the Freihaustheater directed by Emanuel Schikaneder, the German version of an Italian opera with words by Goethe and music by Domenico Cimarosa (1749-1801) was produced with the title Die vereitelten Ränke. The Singspiel Jery und Bätely with words by Goethe and music by Conradin Kreutzer (1780-1849) had its premiere in 1810 in the Hofburgtheater. Around 1812, during the time he was opera director and conductor in Pressburg and Baden-Vienna, Johann Christoph Kienlen’s Singspiel with Goethe’s text, Scherz, List und Rache, was written38 and must have had its premiere in one of the two theatres – and thus in the outskirts of Vienna. After nothing came of a Faust project of Beethoven’s, Josef Bernard wrote a Faust libretto – a version of Goethe – for Louis Spohr (1784-1859); his big two-act Faust opera, written in Vienna in 1813, had its premiere in Prague in 1816 and its first Viennese performance in 1818 in the Theater an der Wien. In 1827 it was also in rehearsal in the Kärntnertortheater. In the Theater an der Wien in 1816 the five-act melodrama of Ignaz Seyfried (1776-1841) had its premiere (with August Ernst Klingemann’s version of Goethe’s text). It remained a success right into the second half of the nineteenth century.39

Of the music for Goethe’s plays we need only refer to Beethoven’s Egmont music, op.84, with an overture and nine vocal and instrumental numbers for which he was commissioned by the Hofburgtheater in 1809. Since the composer was not finished on time, the play received its first performance there in 1810 without Beethoven’s music, which finally came to be heard for the first time in the fourth performance. It is, right up to the present day – but now only in the concert hall – the best known music to a dramatic text of Goethe.

Footnotes

1 Helmut Barak, ‘Goethe im Hofburgtheater’, in: Goethe und Österreich (Vienna, 1999), p.98.

2 Gustav Gugitz, ‘Die Wiener Stubenmädchenliteratur von 1781’, in: Emil Karl Blümml – Gustav Gugitz: Altwienerisches 1 (Vienna, 1921), pp.28-64 (p.38).

3 Gustav Gugitz, Das Wertherfieber in Österreich (Vienna, 1908).

4 Barak has collected examples, partly with relevance to music, pp.87-196.

5 Caroline Pichler, Denkwürdigkeiten aus meinem Leben, ed. Emil Karl Blümml, 1 (Munich, 1914), p.139. ‘Werther, as a novel, left me cold, though I found the psychological truth of the characters, the profound understanding of the human heart and the descriptions of nature etc. extremely attractive.’

6 ibid. ‘[…] and both my mother and I were surprised that the impression these works made on me was just the opposite of what was expected or feared. […] My imagination, the agitation of which one had most feared, remained calm.’

7 Sammlung Deutscher Lieder für das Klavier.[...] I (Vienna: Joseph Edler von Kurzböck, 1778), N.5. Copy consulted in the Archiv der Gesellschaft der Musikfreunde in Vienna, Cat. N. VI 4203 (Q 10633).

8 ibid., N.16

9 Sammlung Deutscher Lieder für das Klavier. [...] III (Vienna: Joseph Edler von Kurzböck, 1780), N.14. Copy consulted in the Archiv der Gesellschaft der Musikfreunde in Vienna, Cat. N. VI 3974 (Q 5579).

10 Facsimile edition with an epilogue by Alfred Einstein (Vienna-Leipzig, Zürich, 1936.) An identical facsimile edition done by collotype and with the same commentary was published without the publisher’s name and undated. On a label glued to the inside cover it was claimed that this manuscript was ‘the first collotype reproduction of the original’. There were 100 numbered copies. The text of this label mentions that supposed ‘chance’ mentioned in footnote 13 below. It says: ‘Only in one single case has that ideal combination of the purist musician and the greatest poet come about by chance: in ‘Veilchen’. (Nur in einem einzigen Fall ist jene ideale Verbindung des reinsten Musikers mit dem größten Dichter durch Zufall zustande gekommen: im ‘Veilchen’.) Copies consulted in the library of the Gesellschaft der Musikfreunde in Vienna, Cat. Nos 23619/161 and 23620/161.

11 Ulrich Konrad – Martin Staehelin, ‘allzeit ein buch’, in: Die Bibliothek Wolfgang Amadeus Mozarts (Wolfenbüttel, 1991), p.110.

12 Max Friedländer has some examples of still earlier settings outside the Viennese area: Gedichte von Goethe in Compositionen seiner Zeitgenossen, ed. Max Friedländer (Weimar, 1896), pp.12-17.

13 Against this Ilija Dürhammer maintains: ‘It is likely that Mozart had not had Goethe in mind, and that Mozarts ‘Veilchen’ setting was more due to chance’ (‘auch mehr einem “Zufall” zu verdanken’). (Ilija Dürhammer: ‘ “Göthe’s musikalisches Dichter-Genie”. Goethes Bedeutung für die österreichische Musikgeschichte von Mozart bis Mahler’, in: Goethe und Österreich, p.66 and p.78). This opinion is not to be suppressed here even if, because of the broader considerations he has outlined, the author cannot agree with it.

14 Gesaenge mit Begleitung des Pianoforte von Anton Eberl. Works 23 (Vienna: Kunst- und Industrie-Comptoir, No. 298, 1804). Copy consulted in the Archiv der Gesellschaft der Musikfreunde in Wien, Cat. N. VI 11987 (Q 5425).

15 Eberl’s letter is published in: Goethe und Österreich. Briefe mit Erläuterungen II., ed. August Sauer (Weimar, 1904), p.76.

16 ibid., p.20.

17 ibid., p.21.

18 XVI Lieder von Göthe in Musik gesetzt und dem Dichter gewidmet vom Grafen Moriz von Dietrichstein (Vienna: Artaria, No. 2120, 1811). Copy consulted in the Archiv der Gesellschaft der Musikfreunde in Vienna, Cat. No. VI 11975 (Q 7549).

19 Goethe und Österreich. Briefe mit Erläuterungen, pp.77-79. ‘Without my being in a position to judge the compositions aesthetically, may I say that their charm and a certain original character made them very pleasing. It gives rise to interesting reflections when one sees how the composer, when he makes the song his own and brings it to life in his own way, gives the poetry a certain manysidedness which it can in no way have of itself. This makes it clear that something that seems simple and limited can, if it is effective, give rise to the most manifold productions.’

20 ibid. ‘It would be very pleasant for me to hear these songs performed by the composer, or at least in his presence, because they could thereby only be enhanced. In the meantime our singers and musicians have treated them with much love and attention and so have given me many an hour of pleasure.’

21 Goethe und Österreich. Briefe und Erläuterungen, p.77.

22 Ludwig van Beethovens Briefwechsel. Gesamtausgabe, ed. Sieghard Brandenburg, 5 (Munich: 1996), p.36. ‘both seemed to me to be communicable through music. How nice it would be for me to know whether I have succeeded in combining my harmony with yours; even instruction, which I would accept as truth, would be extremely welcome.’

23 ibid. ‘how highly I would value any sort of general comment at all about the composing or setting of your songs!’

24 Allgemeine Musikalische Zeitung, 24 (Leipzig, 1822), columns 674-76.

25 Sammlung deutscher Lieder mit Begleitung des Claviers. Der verdienstvollen Sängerin Therese Fischer zugeeignet vom Freiherrn Niklas von Krufft (Vienna: Anton Strauß, 1812). Copy consulted in the Archiv der Gesellschaft der Musikfreunde in Vienna, Cat. No. VI 3752 (Q 6406). ‘With regard to the musical treatment of these texts I had a three-fold aim in mind: correct declamation in the spirit of the poems and in relation to all the strophes; the greatest possible clarity and roundedness of the melody; independent piano accompaniment, insofar as this was compatible with the support required by the voice.’

26 ibid. ‘drawn from the classical writers of Germany; some of the poems – like “Würde der Frauen”, “Trost in Thränen”, “Das Lied aus der Ferne”, the Lied from Wilhelm Meisters Lehrjahre – coincided with the choice made by other, excellent composers; many of the poems, so far as I know had never yet been set to music at all.’

27 Zwölf Lieder von Göthe mit Begleitung des Piano-Forte in Musik gesetzt und Ihro Majestät der Königin von Baiern Friederike Wilhelmine Caroline in aller tiefster Ehrfurcht gewidmet (Leipzig: Ambros Kühnel, Plattennummer 818, 1810). Copy consulted in the Archiv der Gesellschaft der Musikfreunde in Vienna, Cat. No. VI 12502 (Q 6286). There was a copy of this edition also in Goethe’s library.

28 Max Friedländer, p.133.

29 Zwanzig Lieder mit Begleitung des Piano-Forte in Musik gesetzt und Seiner Kaiserlichen Hoheit dem Allerdurchlauchtigsten Erzherzog Rudolph von Oesterreich in allertiefster Ehrfurcht gewidmet (Vienna: Pietro Mechetti, 228, 1813/14). I consulted Kienlen’s copy dedicated to the Archduke Rudolph in the Archiv der Gesellschaft der Musikfreunde in Vienna, Cat. No. VI 12503 (Q 10544).

30 Goethe und Österreich. Briefe und Erläuterungen, p.XXXVI.

31 Sechs Gedichte für eine Singstimme mit Begleitung des Piano in Musik gesetzt und Herrn Michael Vogel [recte: Vogl] k.k. Hof-Opern-Sänger gewidmet (Vienna: S. A. Steiner & Comp., 3014 1820). Copy consulted in the Archiv der Gesellschaft der Musikfreunde in Vienna, Cat. No. VI 12651 (Q 7321).

32 Czerny’s manuscript is in the Archiv der Gesellschaft der Musikfreunde in Vienna, Cat. Musikautographe Carl Czerny 27a.

33 ‘dem Dichter verehrungsvoll’ is the formulation used on the title page of the first edition which appeared with Anton Diabelli & Co. in Vienna.

34 Goethe was assuming that the second part of the Zauberflöte would be played in conjunction with the first part, but since the latter was, at the time, only being presented in Schikaneder’s Vorstadttheater, Goethe would have had to apply to the Baron Braun, the Theatre Director. It was unlikely that Braun would suddenly stage Part One for that reason alone. A further impediment would have been the competition with a rival theatre. The question of censorship would have played a part: Goethe would have had to submit his sequel to the Viennese authorities for their approval. It is certain that they would have required some changes. For further correspondence on this project see Goethe und Österreich. Briefe und Erläuterungen, pp.3-8.

35 ibid., pp.44-48.

36 For further discussion of this theme see Otto Biba, ‘Schubert’s Position in Viennese Life’, NCM (1979), NCM 3/2 (1979), pp.106-13.

37 ibid., p.XXXVI

38 See Othmar Wessely in: Die Musik in Geschichte und Gegenwart. Allgemeine Enzyklopädie der Musik 7 (Kassel-Basel-London-New York, 1958), column 885.

39 This overview is taken largely from Anton Bauer: Opern und Operetten in Wien (Graz-Köln, 1955).