2 | Goethe and Zelter: An Exchange of Musical Letters

Lorraine Byrne

Goethe’s Musicality Revealed

Goethe’s correspondence with Zelter, which began in 1799 and lasted until 1832, the year in which both friends died, is an important source for the poet’s understanding of music, and testifies to his musical intelligence. In order to survive life, Goethe was convinced that a person needed the soothing power of music, above all song, and in his letters to Zelter the poet’s genuine need for music in his life is apparent. He regularly attended concerts and soirées, and when approaching sixty he organized a Singschule in his house to make music under his direction. Goethe’s interest in vocal music led him to compose a rhythmic setting of ‘In te, Domine, speravi’ for four-part choir. A year later, in the winter of 1813/14, he asked Zelter to compose a setting of ‘In te, Domine speravi’ for the same medium in exchange for some quodlibets for his Liedertafel.1 The composer acquiesced and, in comparing the two renditions, Goethe recognized the influence of the Baroque composer, Jommelli, on his own compositional style.2

Goethe’s Hauskapelle was the fulfilment of a dream he wrote about in Wilhelm Meister. In this novel he saw himself as Serlo, who:

ohne selbst Genie zur Musik zu haben oder irgendein Instrument zu spielen, wußte ihren hohen Wert zu schätzen […] Er hatte wöchentlich einmal Konzert, und nun hatte sich ihm durch Mignon, den Harfenspieler und Laertes, der auf der Violine nicht ungeschickt war, eine wunderliche kleine Hauskapelle gebildet.3

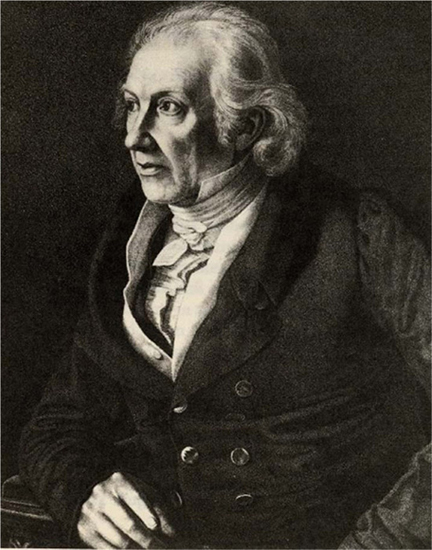

Figure 2.1 Carl Friedrich Zelter, Lithograph by Ludwig Hein from the Oil Painting by Karl Begas

Through Goethe’s letters to Zelter we know what music was performed and how his house-music was arranged. The first part of the programme was always dedicated to sacred music; the secular works were usually followed by songs dealing with ‘nature and the world’ and finally – as was the preference of the poet – the evening ended with the performance of humorous songs.4

In addition to his Hauskapelle Goethe attended concerts regularly, yet constant musical activity alone was not enough for the poet. After performances he consulted Zelter about the music he had heard and so we witness his spiritual response to music and his sincere concern to understand the art. The history of music interested Goethe as part of the chronicle of human culture, and his correspondence with Zelter reveals his desire to obtain a picture of musical development in general. In a letter to Zelter dated 14 January 1819, Goethe records a series of instructional recitals in Berka, where Schütz played to him every day for three to four hours at his request:

in historischer Reihe: von Sebastian Bach bis zu Beethoven durch Philipp Emanuel, Handel, Mozart, Haydn, durch, auch Dusseck und dergleichen mehr.5

In a similar fashion, he urged the twenty-two-year old Mendelssohn to play him pieces in chronological order and then to explain what each composer had done in order to further the art. While Goethe’s relationship with both musicians reveals a certain reliance on an interpreter to bring music alive to him, the poet’s modest technical skill in music should not be taken as definite proof that the poet was ‘unmusical’. Goethe’s lack of skill in score reading and performance did not result from a lack of musicality, but arose from his late start in learning an instrument. While Goethe grew up with music, he was fourteen before he learned to play the piano; flute and cello were studied in later years. Goethe refers to his incomplete musical education in his correspondence with Zelter, yet, conscious of this handicap, he was industrious in acquiring a greater knowledge of the art.

Goethe’s love for the melismatic melodies of Bach and Handel reveals the independence of his musical judgement and suggests how his opinion on setting words to music is not as conservative as is traditionally held. His own perception of Bach stands in complete contrast to the social aspect of music-making and performance. Lying down with his eyes shut in the Juno room of his Frauenplan house, in a state of heightened experience, Goethe listened attentively to Schütz’s interpretations of Bach’s preludes and fugues. This took place in November 1818.6 Even before this significant encounter he acclaimed Fräulein Hügel’s performance of Bach in 1815, many years before Mendelssohn’s Berlin performance of the St Matthew Passion in 1829 heralded the revival which brought Bach’s music to the attention of the public at large. The signficance of Goethe’s encounter with the music of Bach is apparent in a letter to Zelter in 1827, where he again records the private recitals in Berka and describes how his entire attention was directed at the transacoustic background of the music:

Wohl erinnerte ich mich bei dieser Gelegenheit an den guten Organisten von Berka; denn dort war mir zuerst, bei vollkommener Gemütsruhe und ohne äussere Zerstreuung, ein Begriff von eurem Grossmeister geworden. Ich sprach mir’s aus: als wenn die ewige Harmonie sich mit sich selbst unterhielte, wie sich’s etwa in Gottes Busen, kurz vor der Weltschöpfung, möchte zugetragen haben, so bewegte sich’s auch in meinem Innern, und es war mir, als wenn ich weder Ohren, am wenigsten Augen und weiter keine übrigen Sinne besässe noch brauche7

Listening to Schütz’s performance, Goethe experienced the very essence of Bach’s music, its inner coherence and timelessness. When Goethe speaks of eternal harmony, he is, of course, alluding to the classical idea of a numerically structured cosmic harmony, which he believed to have witnessed upon hearing Bach’s music. He describes Bach’s instrumental music as resounding metaphysics, as the revelation of musica mundana, which gave him a sense of inwardly participating in the cosmic order. Within the framework of Goethe’s Theory of Sound, enclosed in a letter to Zelter in 1826, the music of Bach would be classified in terms of numerical laws. In this way it contrasts with the anthropocentric, organic dimension of music, whose medium is the human voice, and with which Goethe ultimately had greater affinity.

As with his scientific studies, Goethe’s portrayal as an Augenmensch is complementary to his musicality, for he often translated the effect music had upon him into pictorial terms. Various images contained in the correspondence show how Goethe sought to capture the gestures of music pictorially, in a way which altogether matched the basic nature of music. During his visit in 1830, Mendelssohn reports that upon hearing the beginning of Bach’s Overture in D Major, Goethe visualized a Baroque feast in tableau form. While scholars have interpreted this form of criticism as a lack of technical ability, Goethe’s method of approach is embedded in the universality of interdisciplinary thinking. His form of musical appreciation revealed relationships which a more academic approach might possibly not have reached. An example of this is his manner of thinking in analogies, which he drew between music, architecture and colour, and which transcended the limits of the individual arts. Goethe considered Leonardo’s Last Supper to be the first fugue in the visual arts and it is reasonable to assume Goethe was open to synaesthesia. In his letters to Zelter Goethe openly acknowledged this visual orientation and he took cognizance of this when listening to music. Unlike Carl Philipp Emanuel Bach who saw the gestures of music-making as a positive contribution to the communication process, Goethe held them to be a disturbing secondary phenomenon, which could divert attention from the unreserved reception of music if they were not in harmony with the music performed. With chamber music the communication between players enhanced the performance, but in opera the orchestral players should be hidden, for their gestures interfered with the musical drama.

Goethe regarded not the eye but rather the ear as the sense organ, which permits the most direct access to the individual’s innermost being. When Goethe found himself incapable of making more than a partial pictorial transformation of a quartet by Mendelssohn, whom he greatly esteemed, he described how it remained ‘in den Ohren hängen’. It remained on his ear until he had time to assimilate it. Conversely, when Mendelssohn played through the first movement of Beethoven’s Fifth Symphony during his 1830 visit, Goethe immediately remarked, ‘Das bewegt aber gar nichts, das macht nur staunen’.8 Goethe’s verbal inadequacy in the face of Beethoven’s Fifth is not an example of the poet’s musical conservatism, as is usually claimed. Like Zelter, Goethe recognized Beethoven’s brilliance as a composer and admired him with awe.9 Beethoven’s music had a diffuse emotional effect upon Goethe: some of it remained beyond rational grasp and was therefore incomprehensible. Interestingly, for Zelter, such incomprehensibility was part of its appeal and in a letter to Goethe in 1831, he considered, ‘Das ist der Vorteil den man beim Genie voraus und davon hat: es beleidigt und versöhnt, es verwundet und heilt; man muß mit.’10 Yet musical enjoyment, which Goethe described to Zelter as a balanced relationship between sensuality and intellect, was, for him, tantamount to intelligibility. By not being accessible to the intellect, Beethoven’s instrumental music embodied the daemonic for Goethe, something he had always inwardly rejected and once defined for Eckermann as that ‘was durch Verstand und Vernunft nicht aufzulösen ist’.11

One of the most interesting documents in Goethe’s communication with Zelter is his interest in music as an acoustic phenomenon and his discussion of major and minor tonalities. That Goethe was the leader in this discussion, and not reliant on Zelter’s opinion, is evident in his letters to Schlosser where the debate is continued. In contrast to Schlosser, Goethe questions the association of the minor mode with melancholy, and he relates major and minor tonalities to the duality in human nature. For Goethe, the major mode was an expression of all that is objective and connects the soul to the outer world, and the minor tonality is the mode of introspection and concentration. The poet’s preoccupation with musical polarity is revealed through his correspondence with Zelter, and it is clear that he does not always accept the composer’s opinion. While Zelter’s conciliatory response brought the debate to a halt, Goethe reopened the discussion a year before his death, and it is Zelter who agrees with Goethe’s musical opinion. 12 Goethe’s first formal papers on music commenced in 1805, with his translation of Diderot’s Neveu de Rameau.13 What is most significant about Goethe’s writing about music is that he is not merely recycling his reading and the views of others, but is giving his own experienced, passionately felt, existentially authentic insights. In the notes to this work he recognized the depth of his own musical response, and his research on the French composer awakened his interest in other theorists. In a letter to Zelter on 4 January 1819, he mentions his discovery of the theoretician, Johann Mattheson, a contemporary of Bach, whose monumental folio Der Vollkommene Capellmeister he was reading.14 The fact that Goethe was interested in the theoretical background and sought appropriate expert advice strikes us as extremely modern. Inspired by the acoustician, Ernst Chladni and the scientist Ernst Meyer,15 he sketched a treatise on acoustics. Goethe’s Tonlehre is contained in his correspondence to Zelter on 9 September 1826, where he encloses it for the composer’s consideration.16 Although fragmentary in form, Goethe’s Tonlehre is interesting, for it reveals how he approaches music in a scientific way in order to gain a deeper insight into the art.

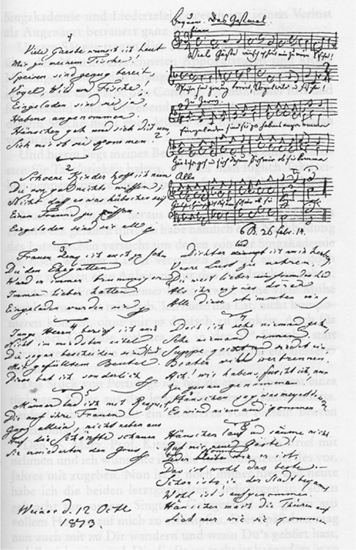

Figure 2.2 Zelter’s Setting of Goethe’s ‘Das Gastmahl’ enclosed in the correspondence (in Goethe’s and Zelter’s own hand)

Goethe’s independent and ingenious reflections upon music, as exemplified by the tonality controversy with Zelter or by his draft of a system of acoustics, derive not least from his opinion that the sensual effect which music exercised upon his imaginative faculty was more important than preconceived aesthetic dogma. For Goethe, theory was the critical penetration of sensual perception, of what is audible as music. In countering Zelter, who held the minor to be a deficient mode on empirical, scientific grounds, it is interesting that Goethe should have used the musician’s ear as an argument: ‘Was ist denn eine Saite und alle mechanische Teilung derselben gegen das Ohr des Musikers?’17 The primary encounter was of paramount importance to Goethe, followed by knowledge through reflection. Thus Goethe gave priority to listening to music. To Friederike Helene Unger Goethe named three qualities which characterized his listening to music: his conviction regarding the unique affective power of music, the frame of mind in which he listened to music, and listening as far as possible, ‘unreservedly’ and ‘repeatedly’. Goethe placed great emphasis on repeated listening, not only because of the importance of increased familiarization, but rather that in the phase of actually coming to grips with the music, described by Goethe as ‘Nachdenken’ (a reflective process), repeated hearing provided him with several chances to check his first impressions and deepen them. Goethe’s personal experience of this phenomenon is described in his letters to Zelter; on one occasion he attended three performances of Mozart’s Il Seraglio in order to gain access to the music. In 1824 he opens up a discussion of Handel’s Messiah inspired by his reading of J. F. Rochlitz’s theoretical study of the work.18 He arranges a performance of Handel’s Messiah in his home and attends rehearsals to test out what he has read. He discusses the work with Zelter and relates how his understanding becomes clearer in performance.

Scholars far too seldom realize what extraordinary wide-ranging knowledge of the repertoire Goethe possessed. It included the music of Palestrina, which he had encountered for the first time during his journey to Italy; Byzantine vocal music; and composers right up to his own time, such as Hummel, Beethoven, Schubert, and Mendelssohn. Numerous operas, which had been performed under Goethe’s theatre direction in Weimar, were likewise at his hand. Goethe’s correspondence with Zelter bears testimony to his catholic taste in music and contradicts the perception that the poet blindly accepted Zelter’s musical opinions. While Goethe admired Zelter’s musicological writing and compositions he also recognized the limits of his abilities. In May 1815 he suggests Zelter write a History of Music in the same vein as Winkelmann’s classical histories19 but, like their plans to write a cantata for the Reformation Jubilee,20 Goethe eventually drops the idea, recognizing Zelter’s talent was realized in smaller forms. Even here Goethe did not acclaim Zelter blindly: in a letter to the composer on 14 October 1821, Goethe asks permission to reinstate the poet as he alters the musical rhythm of Zelter’s setting of ‘Derb und Tüchtig’.21 While the beginning of Goethe’s correspondence with Zelter is marked by his dependence on the composer, frequently Goethe opened up their musical discussion and, as his knowledge grew, gradually this reliance diminished. When Zelter tells Goethe that Milton’s tragedy first induced Handel to write his Samson, Goethe is intrigued but finds Handel’s treatment closer to the Bible than Milton’s text which, in his opinion, approached very closely the purport and style of ancient Greek Tragedy.22 Following a performance of a Greek choir at the Easter services in 1808, Goethe remarks on the close relation between the Russian hymns and Sistine chants, and asks Zelter about the origins of Byzantine music.23 Zelter’s reply reveals that Goethe’s musical knowledge had surpassed him in this area and he corresponds with the philologist F. A. Wolf on the music in Constantinople. At the end of their correspondence Zelter himself recognized the reversal in their roles, and in a letter to the poet he admits: ‘you are the only person I know, whose musical judgement offers unique insight and value’.24

Zelter’s relationship with Goethe

Zelter’s relationship with Goethe has been looked at askance, the blunt Zelter being falsely blamed for Goethe persisting in eighteenthcentury concepts of musical aesthetics and ‘ignoring’ composers like Schubert and Berlioz. Ossified into an object of philology, the pedantic tutor of Mendelssohn, Loewe, Nicoli and Meyerbeer, and a solid monument to a philanthropic sense of responsibility to education, today Zelter’s name is only raised in association with Goethe or with composers such as Schubert or Mendelssohn. In comparing a composer of ability with a composer of genius, it is not surprising that Zelter comes out of it badly. If we compare the canon of Zelter’s compositions with Schubert’s compositional oeuvre, the difference between the two composers is clear, without our even listening or reading through it. Yet, looked at in their own light, Zelter’s songs are as good as any Lieder to be found by a contemporary composer other than Schubert, but in performance and musicology we continually underrate his music through such comparisons. In making this observation I am not espousing a Zelter renaissance but am interested in responding to the history of the German Lied against the wider background of German cultural history. Like Reichardt, Zelter’s was a philosophical and a sociological approach to the definition of musical goals. His desire to find a language capable of communicating emotional experience in its simplest and purest form bore something of the same cultural message, as did the nascent ideas of German classicism. Goethe and Zelter recognized song as the innermost unity of poetry and sound. Goethe’s first letter to Zelter on 26 August 1799 praises the unity of words and music in Zelter’s Goethe settings and the composer’s true inclination for making much of their spirit his own. 25 Zelter describes his compositional process to the poet; the correspondence is laden with attachments – suggestions of poems to be set – some of which were taken up: ‘Um Mitternacht’ and ‘Gleich und Gleich’ received their setting this way. The correspondence records settings of some particularly demanding poems of Goethe such as the varied interpretations of ‘Harpers Klage’ composed in 1795 and in 1816, as well as programmatic scenes and musical tableaux such as ‘Johanna Sebus’.26

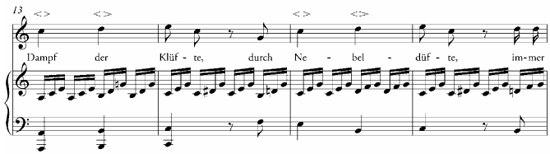

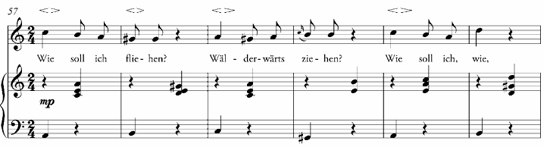

In the correspondence there are many references to popular settings such as ‘Wandrers Nachtlied’ (‘Über allen Gipfeln’, see example 2.1): in 1814 Goethe praises a performance by the tenor, Carl Moltke at his Hauskapelle27 and in 1820 he cites it along with ‘Johanna Sebus’, ‘Um Mitternacht’ as ‘die reinste und höchste Malerei in der Musik’.28

Figure 2.3 The Wooden House on the Gickelhahn at Ilmenau

Figure 2.4 Opposite the Wooden House on the Gickelhahn at Ilmenau

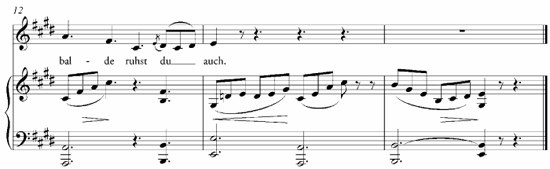

Example 2.1 Zelter, ‘Wandrers Nachtlied’

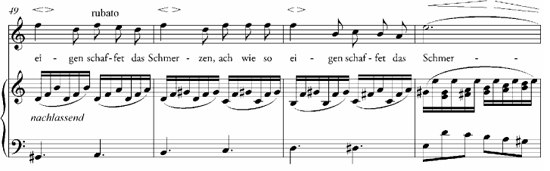

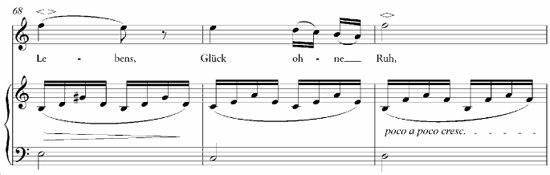

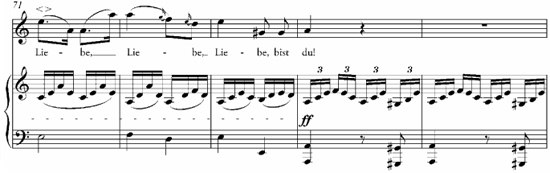

The correspondence also records Goethe’s response to settings of deeply thoughtful poems like ‘An die Entfernte’, which Zelter composed plainly and strophically, as well as his enthusiasm for )’s ‘Rastlose Liebe’, which is remarkably progressive, starting with precipitate declamation and building up to furious, emphatic octave rises (see example 2.2):

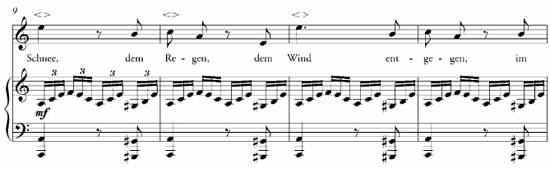

Example 2.2 Zelter, ‘Rastlose Liebe’

Zelter’s musical ability is continually called into question by scholars, yet his letters to Goethe reveal a reflective musician. When he asks Goethe to translate from Latin Jungius’ Harmonie he rewards the poet by discussing the fundamental principles of harmony discussed in relation to the music of Hans Leo Hassler and Palestrina. Later when Goethe sends him a manuscript of 247 chorales by Pachelbel, Zelter considers Pachelbel’s achievement in relation to other composers of chorales from Luther up to Sebastian Bach. 29 Zelter’s correspondence with Goethe chronicles the composer’s artistic growth and the impact he had on the musical life of Berlin. In December 1808 he founded the Berlin Liedertafel, a choral society of twenty-five men – which inspired the formation of other such societies. In addition he established various institutes for teaching church and school music in Königsberg (1814), Breslau (1815) and Berlin (1822) and a student ‘collegium musicum vocale’ in 1830. When he was founder of the Royal Academy of Religious Music in Berlin (1822) and director of the Sing-Akademie (1823), numerous works were staged under his direction. The correspondence chronicles performances of such works as Bach’s motets and cantatas, Handel’s oratorios, Graun’s Der Tod Jesu, Haydn’s Creation and Seasons; Beethoven’s Oratorio, Christus am Ölberge, and Mozart’s Requiem. Under his guidance, the Sing-Akademie became a model for the performance of early sacred choral works with instrumental accompaniment, provided by the Ripienschule, which he founded in 1809. Zelter drew his profound understanding of musical works and sources from the extensive collection of music in the Sing-Akademie Archives and thereby gained a reputation as an authority on early sacred music. In recognition of this he received an honorary doctorate from the University of Berlin in 1829 and was appointed Professor of Music of the Akademie der Künste in Berlin the following year.

Two years before his death, Zelter admitted to the poet, ‘[Ich kann] nicht ohne Töne leben’,30 and Zelter’s discussion of concerts attended provides a valuable chronicle of concert life in Berlin at the beginning of the nineteenth century. His letters provide an important musical record of the music performed in public concerts in Berlin, which included performances of Rossini’s Tancredi, Wilhelm Tell, Othello, The Siege of Corinth and La Donna del Lago; Spontini’s Olympia, Cortes and La Vestale; and Spohr’s Macbeth’.31 Zelter shared Goethe’s love of the human voice and his letters carry detailed descriptions of performances such as those of Anna Milder-Hauptmann in Gluck’s Iphigénie en Tauride; as Emelina in Die Schweizerfamilie and Pamina in the Zauberflöte; Henriette Sontag’s performances of Susanna in Mozart’s Figaro and Desdemona in Rossini’s Othello, and he acclaims Wilhelmine Schröder-Devrient as the leading lady in Ferdinand Reis’s opera, Die Räuberbraut.32 Like Goethe, Zelter criticized the virtuoso cult of individualism, which degrades the musical work to a mere vehicle for the demonstration of technical and artistic dexterity and so works against the listener’s purely musically-oriented interest. At first Zelter complained about the extravagant reception of Paganini’s concerts of his violin concerti, yet when he heard him perform he acclaimed not only his technical virtuosity as a performer, but also his individuality, his grace and intellectual force.33 Other performances of note include concerts given by Moscheles and Hummel, whom Zelter describes as ‘ein Summarium jetziger Klavierkunst indem er Echtes und Neues mit Sinn und Geschick verbindet’.34 Goethe envies musical activities such as Moser’s Quartet evenings in Berlin, and Zelter continually makes an effort to include him. He continually introduced composers and performers to Goethe and a year before both artists died, he wrote to the poet, ‘Dein redlicher Anteil an meinen Produktionen ist mir immer gegenwärtig, so wie ich Dich unter unsern Zuhörern denke’.35 Zelter’s role as inspector of public music education made him attentive to the needs of musicians. And he objected to the high fees Rossini and Spontini received in comparison to the orchestral players.36 He was acutely aware of this on a trip to Vienna in the summer of 1819, during which time he really embraced the musical life of the city. He tells Goethe how Beethoven is praised to high heavens and Haydn is forgotten, though his spirit lives among the Viennese. He relates how Rossini is in vogue and he attends many performances including La Gazza Ladra. He meets Beethoven and Grillparzer,37 befriends Weigl and Salieri, and, astonishingly, he says none of Salieri’s pupils surpass their master.38 The letters contain many topical issues, some directly related to his own work such as the quarrels over the new Berlin Hymn Book. Others more striking include Beethoven’s use of the metronome and the question of authorship in Mozart’s Requiem.39

Zelter’s correspondence with Goethe throws light on the background to the Bach revival. A chart of Baroque composers which he draws up for Goethe reveals his extensive knowledge of the period and includes such musicians as Schütz, Schien and Scheidt, Rosenmüller, A. Scarlatti, Pachelbel and Telemann.40 In their correspondence of 1827, Goethe is fascinated by Zelter’s observation of Couperin’s and Vivaldi’s influence on Bach’s compositional style, and during his trip to Vienna, the composer considers how ‘Mozart steht viel näher an Sebastian Bach als Emanuel Bach und Haydn’.41 He informs Goethe of Mozart’s enthusiastic reception of Bach in Leipzig at a time when Hiller considered Bach’s music dated and raises the question of Baroque influence on Mozart’s style.42 Zelter sends Goethe some autographs of Sebastian Bach, discusses the musical irony in Bach’s biblical settings and comments on the inward nature of Bach’s music. There is extensive documentation of the rehearsals for the first performance of the St Matthew Passion. Zelter relates to Goethe how, ‘Felix hat die Musik unter mir eingeübt und wird sie dirigieren wozu ich ihm meinen Stuhl überlasse’43 and from the orchestral pit he watched Mendelssohn with pride.44 Although in one letter he calls out to Bach, ‘Ich habe dich wieder ans Licht gebracht’,45 he only steps in to conduct a second performance because Felix was giving a series of organ recitals in London and he does not hide from Goethe how the reviews are different, but not intolerably so.46

Zelter’s letters to Goethe provide a fascinating account of Mendelssohn’s development as a composer. He introduces Felix to Goethe in the winter of 1821/22 and after the visit his letters chronicle Mendelssohn’s development. He describes ‘sein erstaunliches Klavierspiel’47 and recounts Mendelssohn’s compositional progress with delight. Between 1822 and 1826 he records the composition of Mendelssohn’s dramatic works: Die wandernden Komödianten; Der Onkel aus Boston oder Die beiden Neffen; Die Hochzeit des Camacho; a Gloria in E flat Major and a Magnificat in D Major for solo voices, choir and orchestra; the Piano Quartet in C Minor, op.1; his Concerto in A Minor for piano and string orchestra; his Double Piano Concerto in A flat Major; his Octet in E flat Major, op.20, and the first movement of his String Quintet, no.1 in A Major, op.18. Characteristically, Zelter recounts Mendelssohn’s ‘schöner Fleiß’48 without any trace of jealousy, admitting, ‘Weiß ich selber nichts Rechts zu machen, halte ich doch meine Jünger an’;49 he relates how Mendelssohn’s development positively delights him and after a private performance of his fourth opera in 1824 he admits, ‘Von meiner – schwachen Seite kann ich meiner Bewunderung kaum Herr werden, wie der Knabe der so eben 15 Jahre geworden ist mit so großen Schritten fortgeht’.50 Goethe responds with delight, recalling Felix’s performance of his Piano Quartet in D Major, op.3, which he dedicated to the poet during his visit to Weimar in 1825,51 and a year later he sends thanks to Felix for the splendid copy of his aesthetic studies.52 Mendelssohn’s travels to Paris in 1825 and 1832, to Scotland in 1829, and his Italian Journey in 1830 are all documented and discussed in Goethe and Zelter’s letters.

Zelter’s humility is evident in his letters to Goethe and it is clear that he recognized the limits of his musical abilities. He recalls how he practised the violin unwearyingly in his youth, performing Tartini’s, Benda’s, Celli’s, and Corelli’s concerti in public; at the same time he recognizes the limits of his technical ability.53 The experience of these years informed his writing of instrumental music including the Viola Concerto in E flat Major.54

In 1808 Zelter described his music as ‘kleinen Herrlichkeiten’55 to the poet Goethe, admitting, ‘Könnte ich nur an etwas Großes kommen. Meine Jahre gehn dahin und es wird – nichts’.56 At the same time he was well able to celebrate those around him. In a letter to Goethe on Christmas Eve 1825, Zelter acclaims a performance of Weber’s Euryanthe. He compares the unfavourable reception of this work in Vienna and Dresden to the warm reception and encouragement the composer received in Berlin. He praises Weber’s intense industry57and is delighted by the celebrations after the performance, remarking:

Daß ich altes Stück dabei nun auch immer sein muß braucht Dich nicht zu wundern, weil ich nicht der Narr sein will mit den Schmälern zu Winkel gehn und mich am Wohlergehn Eines Menschen in der Welt zu ärgern.58

A remarkable example of his humility is found in Zelter’s letter to Goethe on 11 June 1826, where he compares his own setting of a poem by Voss to a setting by his student, Fanny Hensel, and admits, ‘sie [hat] es in der Tat besser getroffen als ich’.59

Conclusion

Goethe and Zelter spent a staggering thirty-three years corresponding or, in the case of each artist, over two thirds of their lives. Zelter’s position as Director of the Sing-Akademie in Berlin and Goethe’s location in Weimar resulted in a considerable correspondence. The 891 letters that passed between these artists contain an important historical record of the music performed in public concerts in Berlin and in the private and semi-public soirées and matinees of the Weimar court at the beginning of the nineteenth century.

Goethe’s letters offer a chronicle of his musical development, from his Classical Weimar years to the final months of his life. While the beginning of Goethe’s friendship with Zelter is marked by his dependence on the composer, Goethe’s awareness of the gap in his musical knowledge inspired him to develop, and gradually his reliance on Zelter diminished. Although they remained life-long friends, Goethe moved away from the composer on many points and at an early stage in their correspondence he recognized the composer’s limitations. He perceived Zelter as an unsuitable composer for Der Zauberflöte Zweiter Teil and for Faust, and though they originally planned to write an oratorio together which could stand beside Handel’s Messiah, he was aware that the composer could not realize this aim. Zelter’s name is usually linked with Goethe, as a composer of his settings, yet what Zelter offered Goethe and bequeathed to history was much more than this. As Kayser and Reichardt correctly realized, Goethe found in Zelter the musical correspondent he had been seeking. In Zelter he found an intelligent and reflective musician whose natural outspokenness, sharp wit and ironic sense of humour engaged the poet. Zelter’s unceasing energy, his passionate devotion to music, and the profound shocks that he suffered, drew Goethe to him. Their correspondence grew increasingly intimate, and the strength of their friendship is shown in Goethe’s letter to Zelter about the suicide of his stepson Karl Flöricke. Here he used the familiar pronoun ‘du’. Zelter was one of the few people after 1800 with whom Goethe shared this form of address. Goethe’s trust is reflected in the openness with which he discusses his various artistic ventures with Zelter. His letters to Zelter offer important insights into the creation and reception of his work, and the richness of themes raised in them establishes this group of letters as being amongst the finest in all of Goethe's correspondence.

A year before he died Goethe wrote to Humboldt that for him in his later years everything became ‘mehr und mehr historisch’.60 In Zelter’s final letter to Goethe, he shares this consciousness, writing: ‘es wäre recht artig, wenn man von Jahrhundert zu Jahrhundert auf die Oberwelt zurückkehren könnte, welches Korn aufgegangen und fortgegangen ist?’61 Like Goethe, Zelter felt compelled to express his artistic ideas in writing – in reviews and music criticism in such journals as Deutschland, Lyceum der schönen Künste and the Allgemeine musikalische Zeitung – but, above all, he was aware of his bequest to music history through these letters. The original German texts, first published in three sizable volumes between 1834 and 1836 by Friedrich Wilhelm Riemer in Briefwechsel zwischen Goethe and Zelter in den Jahren 1796-1832, were prepared with Goethe’s collaboration. Both artists consciously handed down their letters. To borrow Goethe’s words, the letters ‘sind so viel wert, weil sie das Unmittelbare des Daseins aufbewahren’.62 They open the door to Goethe’s and Zelter’s musical lives. As Goethe once wrote:

Briefe gehören unter die wichstigen Denkmäler, die der einzelne Mensch hinterlassen kann. Lebhafte Personen stellen sich schon bei ihren Selbstgesprächen manchmal einen abwesenden Freund als gegenwärtig vor, dem sie ihre innersten Gesinnungen mitteilen und so ist auch der Brief eine Art von Selbstgespräch. Denn oft wird ein Freund, an den man schreibt, mehr der Anlaß als der Gegenstand des Briefes.63

Portraits of Beethoven and Goethe by Joseph Karl Stieler (1781-1858)

Footnotes

1 Goethe to Zelter, 26 December 1813, MA 20.1, p.326.

2 Goethe to Zelter, 23 February 1814, MA 20.1, p.333.

3 Wilhelm Meisters Lehrjahre, HA 7, Book 5, Chapter 1, p.283. Serlo ‘knew how to appreciate the high value of music without having a genius for it or playing any kind of instrument; […] he had one concert a week and now through Mignon, the Harper, and Laertes, who was good at playing the violin, he had formed a wonderful little Hauskapelle.’

4 See, for example, Goethe’s letters to Zelter on 15 September 1807, MA 20.1, p.163 and 16 December 1807, MA 20.1, p.168.

5 Goethe to Zelter, 4 January 1819, MA 20.1, p.550. ‘in historical sequence selections from Sebastian Bach to Beethoven, including Philipp Emanuel, Handel, Mozart, Haydn, Dusseck too, and other similar composers’.

6 See Goethe’s letter to Zelter, 4 January 1819, MA 20.1, p.549.

7 See Goethe to Zelter, 17 July 1827, Enclosure, MA 20.1, p.1021. ‘On this occasion I of course, recalled the good organist of Berka; for it was there, in perfect repose and without extraneous disturbance, that I first formed an idea of your great maestro. I said to myself, it is as if the eternal harmony were conversing with itself, as it may well have done in God’s breast just before the creation of the world; that is the way it moved deep within me, and it was as if I neither possessed nor needed ears, nor any other sense – least of all, the eyes. See also Zelter’s letter to Goethe, 9 June 1827, MA 20.1, p.1003.

8 Andreas Eichhorn, ‘Goethe als Musikhörer’, in: Goethe Chorlieder (Frankfurt am Main, 1998), p.27. ‘That does not move one at all, it only causes astonishment.’

9 Zelter to Goethe, 14 September 1812, MA 20.1, p.286.

10 Zelter to Goethe, 6 April 1831, MA 20.2, p.1462. ‘This is the advantage we derive from genius: it offends and reconciles, it wounds and heals; one must go along with it’.

11 Eckermann, 2 March 1831, (Stuttgart, 1998), p.486. ‘that which cannot be accounted for by understanding and reason’.

12 See, for example, Goethe’s letters to Zelter on 22 June 1808, MA 20.1, pp.184-85; 31 March 1831, MA 20.2, p.1460 and Zelter to Goethe, 14 April 1831, MA 20.2, p.1463.

13 Goethe to Zelter, 19 June 1805, MA 20.1, p.102.

14 Goethe to Zelter, 4 January 1819, MA 20.1, p.550. See also Zelter’s letter to Goethe, 2 June 1819, MA 20.1, p.561.

15 Goethe to Zelter, 31 January 1803, MA 20.1, p.33.

16 Goethe to Zelter, 9 September 1826, MA 20.1, p.952.

17 Goethe to Zelter, 22 June 1808, MA 20.1, p.186. ‘For what is a string and all its mechanically produced division in comparison with the ear of a musician?’

18 Rochlitz, Die Entwickelung des Messias, in Für Freunde der Tonkunst, Goethe to Zelter, 8 March 1824, MA 20.1, p.788. See also Zelter to Goethe, 20-23 March 1824, MA 20.1, p.796; Goethe to Zelter, 27 March 1824, MA 20.1, p.798 and 28 April 1824, MA 20.1, p.803.

19 Goethe to Zelter, 17 May 1815, MA 20.1, p.383.

20 Goethe to Zelter, 14 November 1816, MA 20.1, p.476.

21 Goethe to Zelter, 14 October 1821, MA 20.1, p.670.

22 Goethe to Zelter, New Year’s Eve 1829, MA 20.1, p.1299.

23 Goethe to Zelter, 20 April 1808, MA 20.1, p.173. Zelter to Goethe, 2 May 1808, p.179.

24 For further development of this theme, see Lorraine Byrne, Schubert’s Goethe Settings (Aldershot: Ashgate, 2003), pp.10-14, and 426-28.

25 Goethe to Zelter, 26 August 1799, MA 20.1, p.7.

26 See, for example, Goethe to Zelter, 6 March 1810, MA 20.1, p.228.

27 Goethe to Zelter, 22 April 1814, MA 20.1, p.344.

28 Goethe to Zelter, 2 May 1820, MA 20.1, p.599. ‘the purest and highest style of word-painting in music’.

29 Zelter to Goethe, 4 April 1824, MA 20.1, p.800.

30 Zelter to Goethe, 4 March 1830, MA 20.2, p.1330. ‘I cannot live without music’.

31 See, for example, Zelter’s letters to Goethe: 27 August 1818 MA 20.1, p.543; 7 June 1820, MA 20.1, p.617; 21 July 1820 MA 20.1, p.625; 27 January 1830, MA 20.21, p.1310; 26 October 1830, MA 20.2, p.1383; 1 November 1830 MA 20.2, p.1387; 27 October 1831, MA 20.2, p.1560.

32 See, for example, Zelter’s letters to Goethe on l3 September 1812, MA 20.1, p.284; 28 October 1827, MA 20.1, p.1074 and 12 April 1830, MA 20.2, p.1342; 10 May 1830, MA 20.2, p.1356 and 12 February 1831, MA 20.2, p.1445.

33 See, for example, Zelter to Goethe, 17 April 1829, MA 20.1, p.1218; 14 May 1829, MA 20.2, p.1227. Goethe to Zelter: 17 May 1829, MA 20.2, p.1230 and 9 November 1829, MA 20.2, p.1275.

34 Zelter to Goethe, 23 May 1826, MA 20.1, p.922; ‘an epitome of contemporary pianoforte playing, for he combines what is genuine and new with feeling and skill.’ See also Zelter to Goethe, 30 April 1821; MA 20.1, p.657; 27 November 1824, MA 20.1, p.823; Goethe to Zelter, 14 October 1821, MA 20.1, p.671.

35 Zelter to Goethe, 14 April 1831, MA 20.2, p.1464. ‘Your honest, sympathetic interest in my music is ever present with me, just as I think of you as one of our audience’

36 Zelter to Goethe, 19 June 1825, MA 20.1, p.854 and 19 May 1831, MA 20.2, p.1475.

37 Zelter to Goethe, 14 & 15 September 1819, MA 20.1, pp.584-85.

38 Zelter to Goethe, 22 & 29 July, 1819, MA 20.1, p.568 and p.573.

39 Zelter to Goethe, 10 May l831, MA 20.2, p.1475 and enclosure to Zelter’s letter to Goethe, 10 August 1827, MA 20.1, p.1021.

40 Zelter to Goethe, 4 April 1824, MA 20.1, p.800.

41 Zelter to Goethe, 28 July 1826, MA 20.1, p.937. ‘Mozart stands much nearer to Sebastian Bach than to Emanuel Bach and Haydn.’

42 Zelter to Goethe, 28 July 1826, MA 20.1, p.936.

43 Zelter to Goethe, 9 March 1829, MA 20.2, p.1207. ‘Felix has studied it under me, and is going to conduct it, for which I am giving up my desk to him’.

44 Zelter to Goethe, 12 March l829, MA 20.2, p.1209.

45 Zelter to Goethe, 9 June 1827, MA 20.1, p.1005. ‘I’ve brought you to light again’.

46 See, for example, Zelter to Goethe, 9 March 1829, MA 20.2, p.1207.

47 Zelter to Goethe, 11 March 1823, MA 20.1, p.729. ‘his marvellous piano playing’

48 Zelter to Goethe, 10 December 1824, MA 20.1, p.828. The quote continues: ‘Sein schöner Fleiß ist die Frucht einer gesunden Wurzel’. ‘His admirable industry is the fruit of a healthy root’.

49 Zelter to Goethe, 17 March 1822, MA 20.1, pp.694-95. ‘Even if I myself fail to produce anything much myself, I keep my students focussed’.

50 Zelter to Goethe, 8 February 1824, MA 20.1, p.785. ‘From where I stand, I can hardly master my surprise, at a youth just fifteen years old, progressing so quickly.’

51 Goethe to Zelter, 21 May 1825, MA 20.1, p.844.

52 Goethe to Zelter, 11 October 1826, MA 20.1, p.954.

53 Zelter to Goethe, continuation of letter dated 7 May 1831, p.1468.

54 Carl Friedrich Zelter (1752-1832) Concerto for Viola and Orchestra in E flat Major (Munich Chamber Orchestra with Harold Schlichtig as soloist and conductor), CD 7 619911 070878.

55 Zelter to Goethe, 3 February 1803, MA 20.1, p.33. ‘small glories’

56 ibid. ‘Could I but achieve something great! My life is passing and nothing comes of it’.

57 Zelter to Goethe, 24 December 1825, MA 20.1, p.889.

58 ibid. ‘You need not wonder that an old artist like myself must always be at hand on these occasions, for I am not such a fool as to go into a corner with begrudgers or to be put out by the prosperity of anyone in this world’.

59 Zelter to Goethe, 11 June 1826, MA 20.1, p.933. ‘She has really caught the spirit of it better than I have.’

60 HABr, 4, p.463. ‘more and more historical.’

61 Zelter to Goethe, 22 March 1832, MA 20.2, pp.1633-34. ‘It would be nice from century to century if we could come back to earth [and see] which seed sprouted and blossomed.’

62 Dichtung und Wahrheit, Anhang, Aristeia der Mutter. ‘are worth so much because they preserve the immediacy of existence.’

63 Schriften zur Kunst, Winkelmann und sein Jahrhundert, Vorrede. ‘Letters belong to the most important monuments which the individual can leave behind him. Living people conjure up for themselves the image of an absent friend to whom they communicate their innermost thoughts. Thus the letter is a kind of conversation with oneself. Often the friend to whom one writes is more the reason for the letter than the object of it.’