6 | Goethe and the Czechs

Goethe among the musical Czechs is a multi-layered and at times frustratingly patchy tale. For example, while Goethe is a potent presence in Czech culture in the first part of the nineteenth century, as the numerous song settings of his poetry by Tomášek attest, he retreats into a somewhat hazy middle distance in what has come to be termed as the national revival in the latter half of the century, a situation that requires explanation. While there had been more than stirrings of a broad cultural awareness of Goethe among the Czechs from the late eighteenth century onward, the heyday of the national revival dates, more or less, from the founding of the Prague Provisional Theatre1 in 1862. This precursor of the Czech National Theatre, which now stands as the principal architectural ornament of nineteenth-century Prague on the banks of the Vltava, opened its doors on 18 November 1862 and had a mission to perform plays and opera exclusively in Czech. Inevitably its repertoire tended to favour native writers in Czech rather than the classics of German drama, although many of the latter were given in translation.

There were, however, a number of anomalies in play at this juncture. Several major figures of the national revival, both literary and musical, the latter including the composers Bedřich Smetana and Zdeněk Fibich, spoke German as their first language. In the case of these two composers, the situation was determined by their relatively comfortable middle-class backgrounds. Dvořák, on the other hand, from a decidedly poor, rural, working-class background, spoke Czech as his first language; indeed, he was unusual in coming both from a more or less impoverished background and being a first-language Czech speaker. While the main thrust of this contribution is orientated to musical connections between Goethe and the Czechs,2 it is, for the sake of a more complete picture, desirable and necessary to reflect on Goethe’s legacy among the Czechs as both a philosophic and literary phenomenon, the latter present, not just in influence, but also in terms of the reception and contemporary significance, within the national revival, of such works as Faust and Egmont.

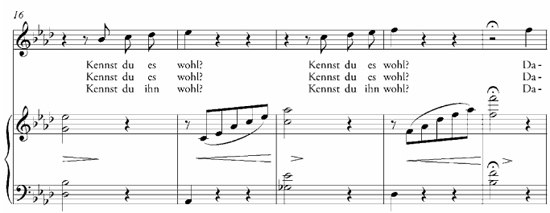

Zdeněk Fibich (1850-1900) was perhaps the most intellectually engaged of all the composers of the Czech national revival; a pronounced modernist when it came to musical theatre, he wrote the first thorough-going Czech Wagnerian Music Drama, based on Schiller’s The Bride of Messina, and revived Benda’s epoch-making melodramas Ariadne and Medea in 1875. This pioneering revivalism was not limited to performance and eventually led to his own trilogy of scenic melodramas, Hippodamie, lasting a near Ring-like three nights in an attempt to realize, as he and his later librettist, Anežka Šulcová, saw it, the full potential of Wagner’s theories of music drama.3 Rather earlier in his career – Fibich was a child prodigy who conducted his first symphony at the age of thirteen – he had set numerous German texts, in fact, a large majority of his songs. Leipzig trained, Fibich was drawn to the poetry of Chamisso, Eichendorff, Heine, Lenau, Rückert and, indeed, Goethe. His nineteen settings of Goethe were made between 1866 and 1871, and he also set for mixed chorus Goethe’s ‘Über allen Gipfeln ist Ruh’. His settings were not composed as parts of cycles, although three, including Mignon’s ‘Kennst du das Land’, were included in a collection entitled Jarní paprsky (Spring sunbeams, 1884). His interest in Goethe was not just confined to settings of poetry: while in Leipzig (1865-67) he provided entr’acte music for Clavigo and a parody duet for tenor and bass based on Faust; there is also a ‘Gypsy song’ for solo and chorus composed for a production of Götz von Berlichingen (1869). These Goethe settings all belong to the 1860s when Fibich’s career might easily have taken him to employment in Germany; as his fortunes prospered in Prague, however, we find, a familiar pattern among Czech composers, Fibich turning more and more to native texts with national resonance.

Bedřich Smetana (1824-1884) showed little interest in text setting until after the opening of the Provisional Theatre when he began forging the line of operas that were the chief propellant of the national revival. There are, however, a few German song settings from 1853, including texts by Wieland and Rückert, though none by Goethe. Unfortunately, Smetana’s overture to Doktor Faust, one of his few genuinely witty pieces, does not have a direct Goethe connection since it was composed for a production in 1862 of a puppet play of the same name by Kopecký. Goethe’s Faust, however, was certainly in the air in the early 1860s in Prague. In 1862 Gounod’s Faust had proved enormously popular with audiences in Prague’s German theatre and extended its hegemony over Czech audiences in the Prague Provisional Theatre. From its premiere in Czech, on 6 July 1867, until the final closure of the Theatre in 1883,4 Gounod’s Faust was given complete 115 times, along with six performances of separate acts, outstripping in popularity any non-Czech operas and being trumped only by Smetana’s The Bartered Bride, which was given 116 times.5 Additionally, in 1861 the Czech Dramatic Theatre had put on successful performances of Goethe’s Faust, Part One. A year later, on 6 December 1862, Prague’s St Cecilia Music Society, one of the Czech capital’s most imaginative concert-giving bodies, gave a performance of Schumann’s Scenes from Faust.6

In fact, Goethe’s first appearance on the stage in Czech in Prague had been with the first part of Faust in 1855 in a translation by Josef Jiří Kolar (Kolar was the translator of choice in both plays and opera in mid-century; he also translated, among a number of plays by Schiller, his Wallenstein trilogy – a cycle with understandably poignant significance for the Czechs); he was also a fine actor and took the role of Mephistopheles in this production. This landmark production was followed by Goetz von Berlichingen in 1856 and Egmont in 1858.

The nature of Czech-language theatre in mid-century Prague needs some supplementary explanation. In this period the Czech capital was changing from a primarily German-speaking city into one in which Czech became the majority language. There had been a continuous tradition of German theatre and opera since the late eighteenth century in the Estates Theatre originally built by Count Nostitz in 1783. Described as a ‘National Theatre’, it was sold by Nostitz’s son to the Bohemian Estates in 1789. Productions in German took place here until 1888 when the company transferred to a new theatre near Prague’s main station (it was renamed the ‘Smetana Theatre’ after the Second World War and yet again renamed after the Velvet Revolution when it became the home of the state opera company). Nostitz’s theatre still exists today and was completely rebuilt (it closed for renovation for eight years and reopened in 1990); it is now mainly associated with Prague’s newest musical industry, namely giving frequent performances of Mozart’s better-known operas, in a way appropriate since the theatre management in Nostitz’s day commissioned and gave the premiere of Don Giovanni.

There was no permanent home in Prague for plays and opera in Czech until the so-called Provisional Theatre was opened on 18 November 1862.7 Productions in Czech were sporadic throughout the earlier part of the century, some, on relatively regular occasions in the 1850s held in the German Theatre. These, largely matinee events, were given on a hand-me-down basis where sets and costumes were concerned and often fell victim to the management dropping the curtain if a production overran.

The Provisional Theatre, a handsome if decidedly small structure, designed by Ignac Ullmann, an ingenious architect responsible for many of the architectural endeavours of the national revival, is now only visible as the back part of the National Theatre which succeeded it. While it is tempting to give the impression that the Provisional Theatre was the kind of temple to culture that its instigators had hoped it would be and the rather more high-minded historical accounts of the national revival have tended to favour,8 the reality is somewhat different. The management which ran the theatre were extremely practical when it came to the profits they were charged with maintaining, since they were engaged on short-term renewable contracts. 9 Aspects of populist entertainment, such as tight-rope walking, and gymnastic displays were mounted alongside plays and opera. As an indication of the nature of taste among Provisional Theatre audiences, Smetana’s populist, rabble-rousing first opera, The Brandenburgers in Bohemia, was a great deal more popular than the rather more lofty, if ravishingly lyrical, Dalibor. Reflecting the public predilection for the spectacular, it is little surprise to find Smetana and his librettist, Karel Sabina, incorporating a circus scene into their first comedy, The Bartered Bride. The nature of foreign repertoire also reflected a demotic tone: while Verdi and Gounod were certainly popular, the audiences for the operettas of Offenbach, Johann Strauss and others, particularly in the summer seasons, were among the largest to be found in the theatre.10 This is, to a large extent, explained by the nature of the audience. The intentions of the founders of the Provisional Theatre had been inclusive of the new working classes drawn in to Prague from the provinces by the industrial revolution; thus high art was tempered by popular repertoire.

This might, to an extent, explain Goethe’s somewhat disappointing track record in the Provisional Theatre:

Table 6.1 Productions of Goethe’s plays Faust and Egmont

in the Provisional Theatre

Faust |

Egmont |

|

1863 |

0 |

1 |

1864 |

0 |

0 |

1865 |

3 |

2 |

1866 |

1 |

2 |

1867 |

1 |

0 |

1868 |

2 |

1 |

1869 |

2 |

0 |

1870 |

1 |

1 |

1871 |

0 |

0 |

1872 |

2 |

1 |

1873 |

2 |

0 |

1874 |

2 |

2 |

1875 |

0 |

0 |

1876 |

1 |

1 |

1877 |

0 |

1 |

1878 |

1 |

1 |

1879 |

1 |

1 |

1880 |

0 |

1 |

1881 |

3 |

3 |

1882 |

2 |

0 |

Totals |

24 |

18 |

The statistics are simple enough: the first performance of a play by Goethe was of Egmont, though apparently without Beethoven’s music on 29 December 1863.11 Faust was given for the first time on 15 March 1864; the performance was accompanied by Lindpaintner’s overture and music, and the splendour of the occasion was advanced by its being the translator-actor J.J. Kolar’s last stage performance as Mephistopheles.

In the succeeding twenty years of the theatre’s existence Egmont and Faust performed an elegant two-step with 1865 something of a bumper year: Egmont was given twice with Beethoven’s overture and incidental music (13 March; 22 July), and Faust three times (30 October; 5 and 23 November) , each time with Lindpaintner’s incidental music. In 1874 the number of performances was reversed with three performances of Egmont (27 February; 30 April; 4 May) and two of Faust (17 May; 27 November). But generally, performances were rarities in the repertoire, one or two a year, until 1881 when both were given three times (Egmont: 8 March; 23 May; 24 September; Faust: 13 February; 12 March; 13 May). Bearing in mind the theatre management’s ready tendency to reflect public response, it is possible that the overwhelming popularity of Gounod’s operatic treatment of Faust froze the play off the stage; there is also the question that in a repertory company of actors adopting roles that settled fairly quickly, performances of Faust perhaps fell victim to the retirement of actors. It is possible to discount theories of anti-Germanism relating to the repertoire since Schiller, to take but the most prominent example, was frequently performed in the theatre. Apart from opera, Faust had other incarnations on the Czech stage, namely a series of parodies. These included one entitled Doctor Faust and his little home-made hat by Hopp and another by members of theatre’s company. 12 Ironically, these might have guaranteed the sporadic performances of Faust the play as a way of touching base, a means of reminding the ready audiences for parodies of the fountainhead for their enjoyment.

Goethe on stage in the Czech lands was not just a metropolitan phenomenon: performances of Faust and Egmont were given in provincial theatres in Hradec Kralové and Brno in the nineteenth century. Once Kolar’s translation was felt to be somewhat dated, a new one of very real literary distinction was provided by Jaroslav Vrchlický – a kind of Czech Tennyson who was arguably the greatest native Czech poet, and certainly the most prolific, of the nineteenth century. Vrchlický was an avid translator of literary epics from the Renaissance to his present day.

The fact that there are no Czech Goethe operas is not surprising, even apart from the comprehensive popularity of Gounod’s Faust. Subject matter for both comic and serious opera was overwhelmingly related to national material. Where composers did tend toward non-national material, the leanings favoured mid-nineteenth-century modernism, in other words subjects suitable for Wagnerian music drama – Schiller’s The Bride of Messina provided Fibich and his librettist, Otakar Hostinský, with the basis for the most thorough-going Czech music drama of the national revival; for his epic retelling of the Hippodamie legend in melodrama over three nights Fibich used suitably classically-orientated libretti by Vrchlický; the same author also provided Dvořák with the text for his last opera, Armida, based on episodes from Tasso’s Gerusalemme liberata.

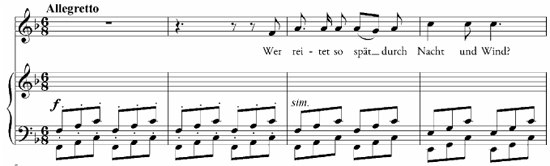

There was, however, one occasion when Czech musical nationalism’s founding father and Goethe came together. In Smetana’s musical treatment of ‘Der Fischer’ (in Czech, Rybář) we encounter one of the real curiosities of the Czech national revival. A very popular entertainment in Prague in the 1860s and 70s was the so-called živý obraz – better known to English-speaking audiences by its French title, the tableau vivant. Capitalizing on the popular appeal of these entertainments, Smetana contributed to a concert designed to raise funds for the completion of St Vitus Cathedral.13 For a concert on 12 April 1869, Smetana provided the music for three tableaux vivants; the first was an arrangement of music from The Bartered Bride – which included the first chorus – a suitably uplifting presentation entitled the Judgement of Libuše (Libušin soud), based on an episode from Czech historical mythology, and a treatment of Goethe’s ‘Der Fischer’. This last is best described as a melodrama in which the poem, against a musical background with an eye-catching backdrop enhanced by atmospheric lighting, is recited. This single ‘setting’ of a text of Goethe by Smetana poses a conundrum since it is, to all intents and purposes, a reduction of the opening of Wagner’s Das Rheingold. Although this preludial portion of Der Ring was not premiered until 22 September 1869, some months after the debut of Rybář, its vocal score had been published eight years earlier (1861). Smetana’s homage to Wagner’s evocation of the depths of the Rhine was almost certainly prompted by the nature of the poem itself, presented here in a somewhat histrionic translation mirroring the Czech version Smetana used: 14

Table 6.2 Goethe ‘Der Fischer’

Der Fischer |

Rybář |

The Angler |

Das Wasser rauscht’, Ein Fischer saß daran, Sah nach dem Angel ruhevoll, Kühl bis ans Herz hinan. Und wie er sitzt, und wie er lauscht, Teilt sich die Flut empor: Aus dem bewegten Wasser rauscht Ein feuchtes Weib hervor. |

Znívody šum Tam rybář na břeh sed, Zřel za udicí klidně v hloub A jeho srdce – led. A jak tu tiše naslouchá, Vod rozčeří se klín A ve vln šumu pozvedá Se vlhké ženy stín. |

The water roars, A fisher sits nearby. Calmly he looks at his rod, Calm, too, is his heart. And as he sits and as he looks The waves rise and part. Out of the roiling waters, A woman rises from the depths. |

The metaphysical seduction that ensues is too well known to require further elucidation, but the poignant point for Prague audiences is the image of the woman from the waters who draws the fisherman into her welcoming depths. Watery things are afoot, and the concert at which this version of ‘Der Fischer’ was premiered was given in a hall on the Sophie (Žofin) Concert Hall on an island in the river Vltava, the Rhine equivalent for Czech audiences. Perhaps, more importantly, the water imagery that Smetana evokes so successfully via Wagner is the start of an inheritance prompted by Goethe which bore rich fruit. Smetana’s symphonic poem Vltava, from the cycle My Country (Má vlast) makes use of this kind of water imagery and, the greatest of all Czech evocations of watery depths, Dvořák’s opera Rusalka, is soaked in the atmosphere that rises mist-like from this curious piece.

What is clear, where the Czech tradition is concerned, is that Goethe’s influence is apparent, if somewhat sporadic, and also subtly inherent. In fact, Goethe’s influence among the Czechs at its most significant might best be described as endogenous, an influence that grew within the development of the national revival. For evidence of this influence, it is necessary to look back toward the late eighteenth century and Goethe’s relationship with Johann Gottfried Herder whose writings, both philosophical and otherwise, not only underpinned the politics of the Czech national revival, but provided part of the seed corn of that revival.15 A seminal episode in advance of influence was the period in 1771 when Goethe went into the countryside of Alsace in search of German folksong. Of the twelve songs that Goethe sent to Herder three found their way into the philosopher’s influential collection ‘Folksongs from many lands’ (Volkslieder 2 vols, 1778-79 which is better known under the title, Stimmen der Völker in Liedern (1807)). In his landmark biography, Boyle was exaggerating only a little when he described Goethe as ‘[…] one of the very first field-workers in German folklore’.16 Goethe’s model and the fruits of his labours proved to have significance well beyond the borders of Germany.

Although it is far too easy to over-rate, particularly in the cases of Smetana and Dvořák, the role of Czech folksong in the national revival, a vital source for the Czech self-image was founded on folksong collecting. Jan Harrach’s initial instructions to potential composers of Czech opera for the Provisional Theatre was the distinctly Herderian command that comedies should make use of the songs of the Slavic peoples of Bohemia, Moravia and Silesia. 17 Among the Slavs, the Czechs came to formal folksong collecting relatively late; the Russians had been hard at it in the early nineteenth century followed in short order by the Poles, the Ukranians and the Slovenians. The first significant stirrings in the Czech lands were prompted by an official Austrian body, the Gesellschaft der Musikfreunde of Vienna. This institution charged provincial governments within the Austrian empire with fostering the collecting of folksong. An early result was a volume of Böhmische Volkslieder published in 1825 and edited by Jan Ritter z Rittersberku and Friedrich Dionys Weber, which comprised 300 Czech songs, 50 German songs and 50 instrumental dances.18 Of greater local significance for the Czechs were the activities of the poet František Ladislav Čelakovský who, heavily influenced by the philosophy of Herder and Goethe, 19 sought to bring about a renaissance of the Czech language through the revival of folk poetry. While Herder was certainly crucial in providing inspiration for Čelakovský, the most important influence was the poetry of Goethe: without doubt, Faust, about which Čelakovský wrote at length, but in the case of his approach to folk poetry and his own work, the poetry and Volkslied style promulgated by Goethe. Čelakovský’s three volumes of Slavonic Folksong (Slovanské národní písně), published between 1822 and 1827, and comprising mainly verse with only a few melodies, were, in a sense, the first pebbles dislodged in what rapidly turned into an avalanche. Key ventures were the folksong collecting activities of František Sušil and Karel Jaromír Erben: Sušil eventually published some 2500 Moravian folksongs (published in seven instalments it was complete by 1860: Moravian folksongs with tunes included with the text; Moravské národní písně s nápěvy do textu vřaděnými); Erben did much the same in volume for Bohemian folksong (tunes 1862, texts 1864: Czech folksongs and nursery rhymes; Prostonárodní české písně a říkadla). As well as providing the Czechs with the authentic article, Erben produced, in 1853, a sensationally successful volume of ballads based on folk sources entitled A Garland of National Tales (Kytice z pověstí národních, 1853). Erben was a huge admirer of Goethe and had translated ‘Erlkönig’ into Czech. In many ways the atmosphere of this, one of the most popular and famous of Goethe’s works, hovers over the poems of Erben’s Garland, notably the ‘Water Goblin’ (Vodník). One of the most atmospheric and successful of Dvořák’s four late symphonic poems based on poems from Erben’s Garland20 was a version of the Erlkönig-shaded ‘Water Goblin’.

While Goethe’s influence, whether endogenous or by proxy as in the case of Erben on Dvořák, was crucial in the Czech national revival, there is a much more material link between his poetry and the Czechs in the shape of the forty-three Goethe settings by Václav Jan Křtitel Tomášek (1774-1850).21 Tomášek’s long life spanned the late classical period, early romanticism and the somewhat faltering early days of the national revival. Tomášek’s musical education was a classic of the Bohemian type: from a far from wealthy mercantile family, he was taught music, as so many were, in the rural locality, graduating at nine to elementary school in Chrudim – a small town – where he studied singing and the violin. In his early teens he gained a scholarship to the Minorite monastery in Jihlava – had he been born a generation earlier he might well have studied, as did so many others, in a Jesuit seminary, but the order had been dispersed in 1775. From here, Tomášek went to Prague to Gymnasium in the Lesser Town (Malá strana) and went on to study, among other subjects, philosophy and law at the Charles University. A formative musical experience in Prague in 1790 was a performance of Mozart’s Don Giovanni.

With no conservatory in Prague at this stage, music for Tomášek was largely a selftaught art. In 1806 he was appointed as music tutor to the aristocratic Buquoy family; Count Buquoy was a man of broad humanist sympathies and an acquaintance of Goethe. 22 This loose-limbed appointment enabled Tomášek to travel extensively in Austria and Germany where he had the opportunity to meet many of Europe’s musical luminaries. Many of those he did not meet on his travels beat a path to his door in Prague once he had become established as the city’s undisputed musical doyen. His pupil, the critic Hanslick, referred to him as Prague’s ‘Dalai Lama’ or ‘musical Pope’;23 among these visitors were Berlioz, Wagner, Paganini and Clara Schumann. We know about the former visits abroad, and much else, since Tomášek tells us in his autobiography, an extensive and fascinating document, published in six issues of the Prague periodical Libussa between 1845 and 1850. 24 The period covered by these reminiscences runs from Tomášek’s childhood to 1824. It is little exaggeration to say that Tomášek name-dropped for Bohemia while exhibiting a healthy flair for gossip: there were visits to the failing Haydn in 1808, the near completely-deaf Beethoven in 1814, and in 1822 a significant appointment with Goethe.

Before considering this high point in Tomášek’s life, a brief word on the nature of his muse and influences. He was an ardent, not to say devout, Mozartean and an admirer, via his studies with Forkel, of J.S. Bach. The musical life of Prague during his lifetime was not as fecund as might be supposed from snapshots of the city in Mozart’s later years or, indeed, in the national revival. There were few of the institutions that were to guarantee the musical health of Prague later in the century. Indeed, so limited were the opportunities for promising musicians, that the haemorrhage of talent so evident through the eighteenth century continued into the early years of the nineteenth. Tomášek, himself, was unusual in being one of the few who stayed at home; many of his pupils, including Voříšek, Dreyschock and Hanslick, all left to seek their fortunes elsewhere. The most significant institution arrived with the founding of the Prague Organ School in 1830 largely designed to fill the gap left when the Jesuit seminaries were abolished in the late eighteenth century; the consequent decay in the standards of church music was not lost on the founders of this institution which eventually educated the likes of Dvořák and Janáček. Apart from these ventures, musical endeavour in Prague might be described as having fallen into a kind of post-Mozartean gloom in the early decades of the nineteenth century.

Tomášek himself was always ready to espouse the virtues of his beloved Mozart and German music while frequently excoriating Italian composers and their taste, yet his music, once he had reached compositional maturity, from about 1807, has a distinctly early romantic cut. His numerous piano works often bear a generalized resemblance to Schubert, a feature shared by his greatest composing pupil, Jan Hugo Voříšek, and one which was more a case of parallel development than specific influence.

Tomášek’s relationship with Goethe’s poetry was long lasting. It is interesting, if sadly salutary, to reflect that, despite the large number and excellence of his Goethe settings, the songs on which the Czechs focused in the national revival of the 1860s tended to be from Tomášek’s fairly extensive groups of Czech settings, made in order to remind the composer of his native language spoken before he learned German.25 A more fruitful influence on the later Czechs was his various sets of piano pieces: Eclogues, Dithyrambs and Capriccios; revived by Karel Slavkovský in the 1870s, they had a conspicuous impact on Dvořák.

Concerning Tomášek’s relationship with Goethe, the modern reader can lean to a considerable extent on the composer’s own words since there is ample reference to the poet in Tomášek’s autobiography. Tomášek informs us of the extent of his interest in Goethe as follows: ‘I wrote several sets of songs which I sold by subscription’, adding with relish, ‘I wrote them with taste and love’. ‘In the seventh set, which I dedicated to Goethe, there are three ballads.’26 Tomášek was thanked handsomely by Goethe for the songs and the dedication, the poet telling him that ‘Your songs are the best I have come across in years’; 27 since this was written in 1820, Goethe’s comment would have included Beethoven and Schubert in this appraisal.

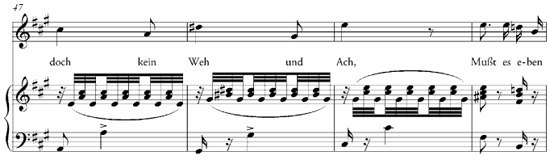

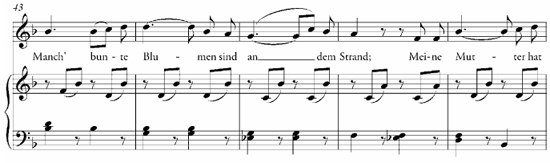

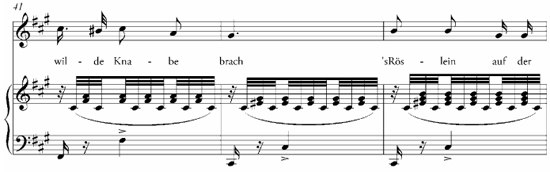

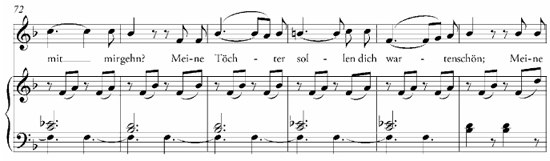

In 1822 Tomášek had the opportunity to meet Goethe who was staying in the west Bohemian town of Cheb (Eger). Tomášek attended on the poet and was greeted cordially; after much conversation, he performed a number of his settings, the first of which was ‘Heidenröslein’. Tomášek’s setting may lack the epigrammatic qualities of Schubert’s, but it has unquestionable charm and freshness including a delightful yodelling effect at the end of the first line. There is one point of close contact with Schubert’s setting, in that the treatment of the word ‘Röslein’ is identical in rhythm and melodic shape. A point of difference from Schubert’s approach is that he does not treat the poem exclusively strophically: for the climax in the third verse, Tomášek goes for minor key drama (see example 6.1).

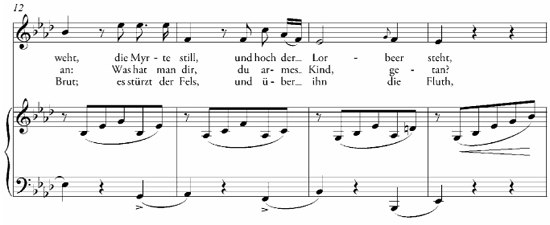

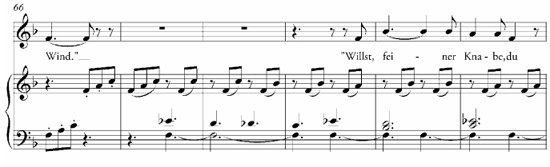

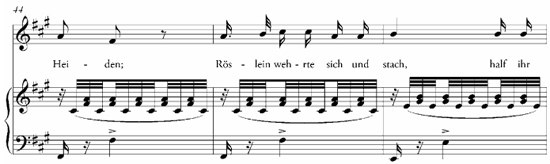

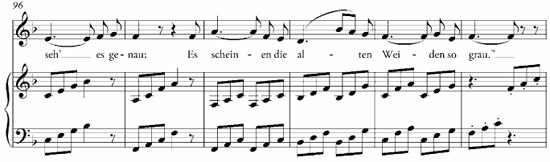

The last song Tomášek performed for Goethe in this impromptu recital was ‘Mignons Sehnsucht’ (see example 6.2). A graceful, dignified setting, it is, unlike Schubert’s, entirely strophic, a point that clearly appealed to Goethe and evoked the following approbation:

You understand the poem – Goethe said this to me after listening to the last-named song; he also said clearly that he was entirely satisfied with my setting of the song […] It seems strange to me that both Beethoven and Spohr so completely misunderstood the song when they composed it. The distinctive mark in the same place in each verse, I would think, was enough to tell composers that what I expect from them is simply a song [Lied]. Evidently, Mignon by her very nature could not sing an aria, but only a song.28

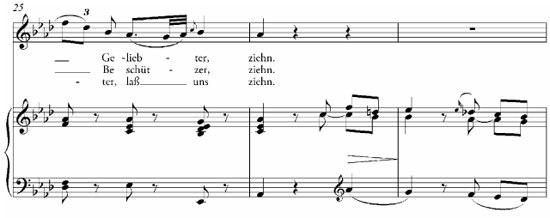

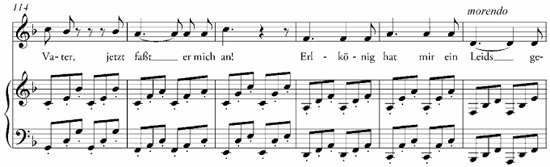

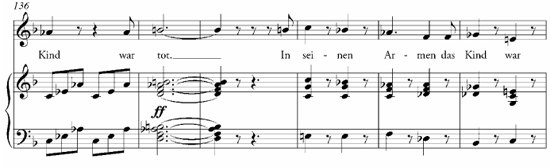

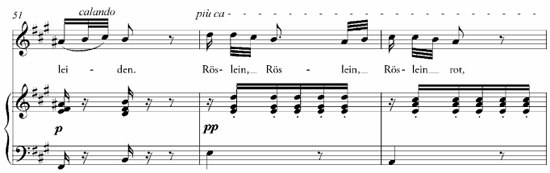

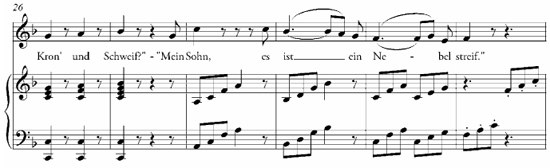

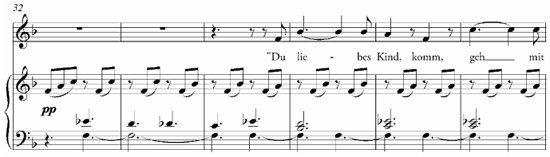

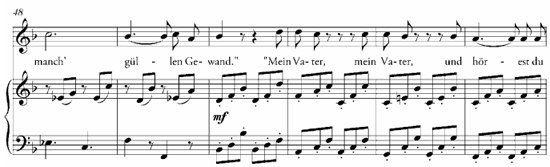

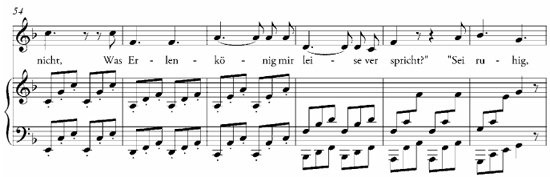

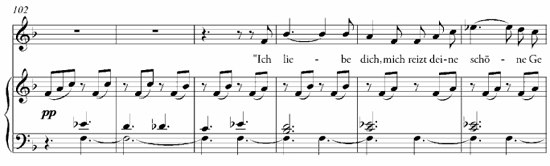

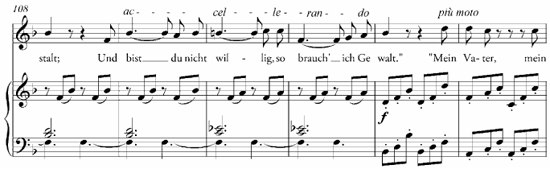

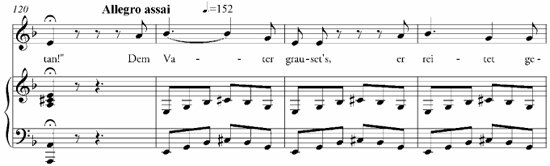

The variety in Tomášek’s Goethe settings is considerable and, as a whole, the collection of songs represents the finest body of Czech Lied settings in the first part of the nineteenth century. While Goethe clearly approved of Tomášek’s uncomplicated approach to his Lied-inspired verse, we do not know the poet’s view of the Czech composer’s treatment of ‘Erlkönig’ (see example 6.3). Schubert’s superbly dramatic setting will always take pride of place, and those of Loewe and Franz are likely to claim precedence in terms of performance history, but Tomášek’s certainly stands high in this company. Effectively through-composed, it develops wonderful impetus and climaxes, with a clear metronome-mark increase, in an Allegro assai dash to the double bar. Eschewing Schubert’s expressionist clinching of the drama, Tomášek repeats the final words, placing ‘todt’ at the top of a bold diminished chord followed by a Neapolitan cadence which unleashes savage descending chromatics in the piano part.

Example 6.1 Tomášek ‘Heidenröslein’

Example 6.2 Tomášek ‘Mignons Sehnsucht’

Example 6.3 Tomášek ‘Erlkönig’

Footnotes

1 The title in Czech was the ‘Královské zemské prozatímní divadlo’ which translates as the ‘royal provincial provisional theatre’.

2 The most substantial survey of Goethe and Bohemia, Johannes Urzidil’s Goethe in Böhmen (Esptein Verlag: Vienna and Leipzig: 1932) [hereafter Urzidil], mentions music rarely and Tomášek hardly more than peripherally.

3 For further information about Fibich’s activities in opera and melodrama in English, see Jan Smaczny, ‘The operas and melodramas of Zdeněk Fibich (1850-1900)’, Proceedings of the Royal Musical Association, CIX 1982-3, pp.119-33.

4 The National Theatre was opened for the first time in the summer of 1881 but burned down by accident days later; the rebuilding of the structure took place in hardly more than two years.

5 For details of performance statistics in the Provisional Theatre see J. Smaczny, The daily repertoire of the Prague Provisional Theatre (Prague: Miscellania Musicologica, 1994) [hereafter Smaczny].

6 I am grateful to Karl Stapleton for supplying this information.

7 The title of the Provisional Theatre arose from its status as a stand-in structure for the planned, and much larger, National Theatre.

8 See Josef Bartoš. Prozatímní divadlo a jeho opera [The Provisional Theatre and its opera] (Prague: 1938).

9 For further information concerning the theatres of Prague in English see John Tyrrell, Czech Opera – in particular ‘Theatres’ (Cambridge: CUP, 1988), pp.13-59 [hereafter Tyrrell].

10 For figures relating to performance see Smaczny, pp.135-37.

11 Figures for the list of performances of Goethe plays in the Provisional Theatre are derived from a ms. list compiled by J. Smaczny from material in the Theatre Centre of the Czech National Museum.

12 Doktora Fausta domácí čepička first given on 13 October 1864.

13 Although begun in the late middle ages, the structure that bears the name of St Vitus standing on the castle height in Prague by the nineteenth century was still without a substantial proportion of its nave and west end. The cathedral was eventually completed in 1929.

14 Czech translation by Otakar Zich.

15 See ed. René Welleck, trans. Peter Kussi, The Meaning of Czech History by Tomás G. Masaryk (Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press, 1974), pp.28-36.

16 See Nicholas Boyle, Goethe: the Poet and the Age, I (Oxford: OUP, 1991), pp.98-99.

17 See Tyrrell, pp.209-10.

18 ibid.

19 See Artur Závodský, František Ladislav Čelakovský (Prague: Melantrich, 1983), pp.144-61.

20 Dvořák set lines of Erben’s text to music which, without text, would be used as the main thematic material of these symphonic poems.

21 These forty-three settings comprise thirty-four solo songs, three duets and four duos; in addition, there are two there are two dramatic scenas based on texts from Faust. The only extensive consideration of these settings in English is to be found in Kenneth DeLong, ‘Jan Václav Tomášek’s Goethe Lieder’, Kosmas 7 (1988), pp.71-90.

22 See Urzidil, pp.169-70.

23 See Eduard Hanslick, Aus Meinem Leben (Berlin: Allgemeiner Verein für Deutsche Literatur, 1911), p.25.

24 V. Tomášek, ‘Selbstbiographie’, Libussa (Prague: 1845-50). There is no complete English translation of this source available although excerpts are printed in A. Loft, ‘Excerpts from the Memoirs of J.W. Tomášchek’, MQ xxxii (1946), pp.244-64. An annotated Czech translation, which was used as the basis of the sections relating to Tomášek’s memoirs in this article, exists: see Zdeněk Němec, Vlastní Životopis V.J. Tomáška [complete autobiography] (Topičova edice v Praze: Prague, 1941) [hereafter Němec].

25 Němec, p.190.

26 Němec pp.238ff.

27 Němec p.239.