7 | Maker, Mother, Muse: Bettina von Arnim, Goethe and the Boundaries of Creativity

Briony Williams

Bettina von Arnim has long been seen as a ‘muse’ to male creators such as Goethe, Beethoven and the Grimm brothers. She herself could be seen to have assisted in immortalizing this role through her semi-fictitious epistolary accounts of her relationships with these men. Her rewriting of much of the correspondence has earned her a great deal of controversy in historical terms, due to the resulting questionable veracity of her account. Bettina herself courted this controversy when she wrote in her introduction to Goethes Briefwechsel mit einem Kinde:

[…] treten Sie abermals hier zwischen mich und das Vorurteil derer, sie schon jetzt, noch eh’ sie es kennen, dies Buch als unecht verdammen und sich selbst um die Wahrheit betrügen.1

This has been assumed to mean that Bettina intended the letters to be taken as reality; but Bettina also gives a hint of her intentions in the book when she wrote to the Weimar Chancellor, Friedrich von Müller, ‘ich spreche nicht von [Goethe], ich spreche zu ihm’.2 These two statements immediately problematize the defining concepts of our use of the term ‘muse’ in relation to the complex figure of Bettina. What exactly was she intending, creatively speaking, in her works? How are we to see her relationship with Goethe? Some answers can be found through exploring the three ways in which Bettina responds to Goethe artistically – through the correspondence, through her poems and through her musical compositions. These last two ‘primary’ creative activities reveal a great deal about Bettina’s own relationship to, and view of, the role of muse.

One difficulty in defining Bettina as a muse in the common conception of the term is that the connection between Bettina and Goethe neither resulted directly in a poem by Goethe, nor is described, at least at face value, in realistic terms in the published correspondence. How, then, did this relationship work in reality?

The word ‘muse’ has often come to define a passive role, particularly of a woman who inspires a male creator in his artistic endeavours, often with herself as the object of his artistic scrutiny. Kimberley Marshall sums up popular contemporary definitions when she writes:

Late-medieval descriptions of the Muses show them making music, inspiring through example as mentors in the specialized disciplines they came to represent. Unfortunately, during the intervening centuries these powerful archetypes have been reduced to an insipid allegory for artistic inspiration.3

Those far more active connotations of the original Greek Muses that were still present in medieval thought are recorded by Ferdinand Comte:

The Muses created what they sang about. By praising the gods, they completed their glory; by boasting of valiant warriors, they wrote their names in history. In this way they collaborated in the ordering of the world […] The disciples of Pythagoras celebrated the Muses as the keepers of the knowledge of harmony and the principles of the universe which allowed access to the everlasting gods.4

Here the word ‘access’ is, I believe, of prime importance in redefining Bettina’s response, in particular to Goethe, in more active terms.

Goethe’s acquaintance with Bettina’s family had already extended over two generations. Bettina’s grandmother was the acclaimed novelist Sophie von La Roche, whose first published book, Die Geschichte des Fräuleins von Sternheim, was an overnight success, and is considered to be the model for Goethe’s Die Leiden des jungen Werthers. Goethe himself wrote of Sophie, ‘Sie war die wunderbarste Frau, und ich wußte ihr keine andre zu vergleichen.’5 Through Sophie’s salons, Goethe also met her daughter Maximiliane, Bettina’s mother. Goethe was considerably attracted to the young woman. Bettina discovered this fact when she read Goethe’s correspondence with Sophie, and it seems to have inspired her to take something of the same role. She began writing to Catherina von Goethe, the poet’s mother, in 1806, and after meeting Goethe himself in 1807, began a correspondence with him as well. Both letter exchanges are ‘documented’ in Bettina’s book, Goethes Briefwechsel mit einem Kinde.

The letters are saturated with Bettina’s views on creativity. Interestingly, she seems to see the act of creation as always being reciprocal – whether it is between two artists, or between an artist and his or her inspiration. In the correspondence with her brother, published as Clemens Brentanos Frühlingskranz, Bettina talked of the ‘four pillars’ of her soul – Goethe, Arnim, music and nature.6 All four are, in Bettina’s view, capable of interplay. Even nature not only inspires but is inspired. Bettina’s image of the shepherd playing his shawm is an example of this view, as he is so in tune with nature that he not only copies the echo he hears, but teaches it new melodies. And music is inspired by words, but the reverse is equally true. The model of creative reciprocity in place in the exchange between Bettina and Achim von Arnim prior to their marriage – where Achim would send her poems, which she would then set to music, which would, in turn, inspire him to add more verses – was not only an exchange between the two creators, but between their creations as well. Not only did Achim inspire Bettina to compose, but his poetry inspired her music in a much more direct way.

This whole notion of inspiration arising from within the work itself is apparent in Bettina’s own poetry. It would seem very clear that Bettina is intending a direct response to specific Goethe poems – the most obvious is ‘Wer sich der Einsamkeit ergibt’, in which the first verse is a direct quote from the Harper’s song in Wilhelm Meisters Lehrjahre. Other poems are less obvious, but still seem to draw their own parallels, for example, the untitled poem in which the narrator stands atop his hill, viewing the scene below, and yearning for the sight of the lost beloved’s rooftop:

Auf diesem Hügel überseh ich meine Welt!

Und könnt ich Paradiese überschauen,

Ich sehnte mich zurück nach jenen Auen,

Wo Deines Daches Zinne meinem Blick sich stellt,

Denn der allein umgrenzet meine Welt.7

One cannot help but be reminded of ‘Schäfer’s Klagelied’. Other examples include Bettina’s ‘Lied des Hemdchens’, a story of what can only be attempted rape, with its overtones of ‘Heidenröslein’, or ‘Das Königslied’, which, like ‘Der König in Thule’, is the story of a king coming to terms with an event in his life before his death.

‘Wer sich der Einsamkeit ergibt’ is a particularly interesting example, not only because it opens with a direct quotation from the Harper’s song, but also because of its overt statements regarding Bettina’s views on the relationship between an artist and a muse. In this parody she has distanced herself from ordinary mortals, from the ‘masses’, and has endowed upon herself the role of priestess in the quasi-religious experience which she believes music to be and as she continually describes it to Goethe in the Briefwechsel.8 Like the original Greek muses, the persona of Bettina within the poem is the medium for communication between the artist and heaven – she gives a gift of ‘the flame of life’. And it does not end there – she lays wreaths at the altar, that is to say she offers her own creations as part of the dynamic of the relationship, and in so doing, achieves immortality for both herself and the artist. Although this could be seen simply as an indication of Bettina’s search for historical permanence, the most interesting aspect of this view of the muse is its possibility for neverending reciprocity – a conceptualization of creativity that is a model of a type of creativity which, in Riane Eisler’s words, moves the process ‘from a linear, cumulative view to a more cyclic, or spiralic one, where repetition and recombination play an important role.’9

Table 7.1 Bettina von Arnim, ‘Wer sich der Einsamkeit ergibt’

Wer sich der Einsamkeit ergibt, Ach der ist bald allein; Ein jeder lebt, ein jeder liebt Und läßt ihn seiner Pein. |

He who devotes himself to solitude Alas, is soon alone. Everybody lives, everybody loves, And leaves him to his sorrow |

Wer sich dem Weltgewühl ergibt, Der ist zwar nie allein. Doch was er lebt und was er liebt, Es wird wohl nimmer sein. |

He who devotes himself to the milling crowd Is, admittedly, never alone What he experiences and what he loves Is mere allusion |

Nur wer der Muse hin sich gibt, Der weilet gern allein, Er ahnt, daß sie ihn wieder liebt, Von ihm geliebt will sein. |

He who devotes himself to the Muse Is willingly alone He senses that she returns his love And that she wants to be loved by him |

Vergöttlicht Lust und Pein. Sie kränzt den Becher und Altar, Was sie ihm gibt, es ist so wahr, Gewährt ein ewig Sein. |

Deifies pleasure and pain, She crowns the chalice and altar What she gives him is so true It gives eternal being. |

Es blühet hell in seiner Brust Der Lebensflamme Schein. Im Himmlischen ist ihm bewußt Das reine irdsche Sein.10 |

The brilliance of life’s flame Blossoms bright in his breast In the heavenly he becomes conscious of The purity of earthly being. |

At times, in Bettina’s life, the term ‘muse’ seems to be almost interchangeable with the term ‘role model’. Bettina herself had a number of role models who could be seen as fulfilling both functions. She grew up in an environment conducive to creative achievement in women. The most important of these was, of course, her grandmother Sophie von La Roche. Not only was Sophie an internationally well-known literary figure even before Bettina was born, she was also financially independent as a result of her writing. Her husband, Georg Michael von La Roche had published a book anonymously, Briefe über das Mönchswesen. It was a politically critical book, and despite the anonymity, his authorship was well-known, and his views lost him his job and career. Overnight, Sophie became the breadwinner of the family with her continuing publications. From 1785 she published almost one volume per year until her death in 1807. Her work encompasses novels, travel memoirs, epistolary novels and, in the two years before her death, two volumes of an autobiography.

There are a number of interesting parallels between Sophie and Bettina, not only through their choices for creative expression – for example, the epistolary novels – but also through their life choices. Both of them married comparatively late and chose partners whom they thought would encourage them in their quest for self-expression. Both women also published most of their output later in life, due to early pressures in their roles as wife and mother. The fact that these other gendered roles encroached on their creative lives means that Bettina’s views on marriage and motherhood need to be taken into account when considering her perception of the gendered role of muse.

Regarding gender issues, two different interpretations of Bettina emerge. One is that she was not interested in her own role as a woman, being far more concerned with her role as an artist. Gert Mattenklott is an advocate of this viewpoint. She names individual women such as Rahel Varnhagen von Ense, Caroline von Schlegel and Bettina von Arnim as being exceptions to the general gendered silence in Germany at that time, but argues that these women were more interested in the rights of the individual to artistic expression than their right as a woman to be heard.11 Yet all of these women fulfilled the role of muse as well as original creator, and were aware of this duality. Surely it is possible that the two perspectives are not mutually exclusive. Despite the emphasis on individual expression, it seems to be the case that these women were aware of the difficulties facing them culturally through their choice to be outspoken. They were also acutely aware of the differences in their means and outcomes of expression from those of men. At one point Bettina wrote to Achim von Arnim, ‘nun sagen meine Lehrer zwar, daß ich nicht dumm sei, sondern besser verstehe wie mancher Mann, aber daß noch viel, viel Zeit dazu gehört, bis ich etwas kann.’12

Another view of Bettina is as an outspoken advocate of women’s issues, as she was on many other social matters. The difficulty with this view is that women’s issues per se do not feature in her writing, although it could be said that there are a number of indirect references. There is, for example, the account of how she and her sister dressed as men to travel to Weimar:

Jetzt rat’ Sie einmal, was der Schneider für mich macht. Ein Andrieng? – Nein! – Eine Kontusche? – Nein! Einen Joppel? – Nein! Eine Mantille? – Nein! Ein paar Boschen? – Nein! Einen Reifrock? – Nein! Einen Schlepprock? – Nein! Ein Paar Hosen? – Ja! – Vivat – jetzt kommen andre Zeiten angerückt – und auch eine Weste und ein Überrock dazu. Morgen wird alles anprobiert, es wird schon sitzen, denn ich hab’ mir alles bequem und weit bestellt, und dann werf' ich mich in eine Chaise und reise Tag und Nacht Kurier durch die ganzen Armeen zwischen Feind und Freund durch; alle Festungen tun sich vor mir auf, und so geht's fort bis Berlin, wo einige Geschäfte abgemacht werden, die mich nichts angehn. 13

In highlighting the issue of male costume as camouflage, Bettina is, I believe, making a very strong statement about how aware she is of gender constructs and limitations in what she achieves. Thus it would seem that Bettina was fully aware of the necessity of action in encouraging freedom of expression for women, but consciously chose to address these issues through her artistic works. Certainly she appears to have thought very carefully of her options before marriage to the poet, Achim von Arnim. Bettina was afraid that the move would stifle her creative endeavours but the apparent environment of mutual inspiration between poet and musician assured Bettina that her creativity would be nurtured. Unfortunately, this was not to be the case – Bettina became confined in a world of domesticity, financial struggle and – worst of all – her husband’s neglect of her creativity. That she understood this in terms of her gendered role in the society of the time is evident from her advice to Philip Hössli that marriage is ‘für das Weib das Einzige, für den Mann blos eine Epoche.’14

Despite Bettina’s frequent depression and feelings of creative inadequacy during her marriage, she was a highly successful mother – all seven of her children survived into adulthood, a rare occurrence at the time. In such a case, it seems difficult to accept Sally Winkle’s view of the adoption of ‘subordinate’ roles for women leading to the loss of their ‘active capability to resolve, lead, create or transform.’15 Bettina seems to have brought her creative self to almost all of these roles in a consciously active and successful way that turned them into primary roles. Although Bettina herself does not seem to have attached the notion of creativity to these other roles, she does make one interestingly explicit comparison between the creativity of a mother and an artist in the passage in the Briefwechsel where she describes music as ‘Mutterwärme’. She writes that music is a mother of twins: ‘eins hatte sie an der Brust, und das andre wiegte ihr Fuß im Takt, während sie ihr Lied sang.’16

Although Bettina was most well-known as an author, her own desire was to be a composer. Music, she felt, expressed what words could not, and she wrote to the poet Caroline von Günderode that she felt more at home within the rhythms of music than those of words.17 It was through composition that she felt most able to converse with other artists – mostly, of course, Arnim and Goethe, and to a lesser degree, with other poets. Formal composition, however, was difficult for Bettina throughout her life, and she constantly struggled to commit her ideas to paper and permanence. She was known as a great improvisational singer – Ludwig Tieck was one of those who admired her talent – and this seems very clear in the structure of her songs. Improvisation could be defined as instantaneous composition in response to a larger context and certainly her melodies seem to unfold in direct and immediate response to a particular text. Bettina’s description of her composition methods outline this process:

Jetzt macht mir’s Freude zu komponieren. – Hymnen der Diane, Päane an Dionysos, von Stolberg übersetzt. – Ja, das macht mir Freude, ich klettere am Abend aufs Dach von der Waschküche, dort erfind’ ich die wunderlichsten Wendungen. Der Himmel rötet sich davon vor tiefem Mitgefühl, und die Sterne drängen sich herbei und lauschen, und Hoffmann lauscht auch, er ist unser nächster Nachbar. Meine Stimme ist durchdringend, wär mein Geist es auch! – Hoffmann kommt am Morgen in die Stunde, kann meine Melodie halb auswendig, was ich mit Bleistift notiert habe, kann er meist besser als ich – über Metrum streiten wir zwar nicht; denn er will durchaus, es soll sein, wie ich’s ursprünglich singe, Takt und Auftakt kommen in Subordination und dürfen nicht ihre herkömmliche Observanz mehr geltend machen, er sagt, wenn ich mich hineinstudiere, so wird’s der Musik eine neue Bahn brechen. Närrischer Kerl! Will mir schmeicheln, mir Mut machen zum Lernen; weiß ich doch, daß er’s mir weismacht, so trägt’s doch meine Begeistrung unendlich hoch!18

Because of the improvisatory nature of much of Bettina’s music-making, her songs have often been dismissed, from Liszt, who wrote to Marie D’Agoult, ‘Ces Lieder qu’elle vient de publier et de dédier à Spontini ne valent pas grand chose,’19 to Max Friedländer, who rather condescendingly acknowledges her ‘für eine Dilettantin erfreuliche Begabung’.20 Of the approximately eighty songs in existence, most are fragments. Nine songs were published in her life-time – two in works by Achim von Arnim, and one collection of seven songs, dedicated to Spontini, director of the Royal Opera.21 All display the same hallmarks of unconventionality.

The two Goethe settings chosen for discussion are prime examples of this refusal to adhere to mainstream compositional rules. They were written approximately twelve years apart – ‘Ach Neige’ in 1810, ‘An Luna’ in about 1822. ‘An Luna’ was written for the singer and actress Amalie Neumann, upon the request of Philipp Hössli, a law student who was a close friend of Bettina’s. The copy in his notebook is dated 28 June 1822. On the surface, the poem of ‘An Luna’ (see table 7.2) could be seen to be an evocation of feminine archetypes, from Luna – the moon, a very common symbol of feminine purity – to the maiden asleep beneath the male gaze. But even here there are echoes of the active muse. In the first verse, Luna has awoken the poet – that is, she has given him both consciousness and the ability to create his verses. She raises him to her side and shows him the object of his inspiration, his beloved asleep in her bed. Her own history is also invoked, through the Endymion myth. Luna has inspired the persona of the poet, who in turn inspires Goethe, Bettina, the performer, and ultimately the listener. But according to Bettina, the circle can also work in reverse, so that the listener can redirect the response of the performer, which in turn literally changes the meaning and content of both music and poetry, all the way back to the Endymion myth. In the myth, Luna saw the shepherd Endymion asleep among his sheep as she went on her nightly rounds, and fell for his beauty. She thereupon went to Zeus and asked if Endymion could be granted eternal youth and eternal life. Zeus granted her wish, and Endymion slept on for eternity, dreaming that he held the moon in his arms, while Luna seduced him nightly. Certainly the kind of eroticizing of the muse role inherent in the myth is completely in character for Bettina; and given Bettina’s penchant for reading her own life in terms of myths, it becomes possible to begin to understand how past and present, conscious and unconscious, intertwine in creative interchange.

Table 7.2 Bettina von Arnim, ‘An Luna’

Schwester von dem ersten Licht Bild der Zärtlichkeit im Trauer! Nebel schwimmt mit Silberschauer Um dein reizendes Gesicht. |

Sister of the sun Picture of tenderness in mourning! Mist swims in silver shimmers Around your lovely face. |

Deines leisen Fußes Lauf Weckt aus tagverschloßnen Höhlen Traurig abgeschiedne Seelen, Mich, und Nachtgevögel auf. |

The tread of your soft foot Awakens from caves that shut out the day Sad isolated souls, Me, and nocturnal birds. |

Forschend übersieht dein Blick Eine unermeßne Weite: Hebe mich an deine Seite, Gönn’ der Schwärmerei dies’ Glück. |

Your glance, searchingly surveys A boundless expanse Raise me to your side Grant my zeal this happiness. |

Und in wollustvoller Ruh Säh der weitverschlagne Ritter Durch das gläserne Gegitter Seines Mädchens Nächten zu. |

And in peaceful ecstasy The knight, driven far, would, through The glass barrier, keep watch over His lady as she slept. |

Des Beschauens holdes Glück Mildert solcher Ferne Qualen Und ich sammle deine Strahlen Und ich schärfe meinen Blick; |

The sweet happiness of contemplation Assuages the torments of such distance And I gather your rays And I focus my gaze |

Hell und heller wird es schon Um die unverhüllten Glieder Und sie zieht mich zu sich nieder Wie dich einst Endymion.22 |

It becomes bright and brighter already Around the unveiled limbs And she draws me down to her As once Endymion did to you. |

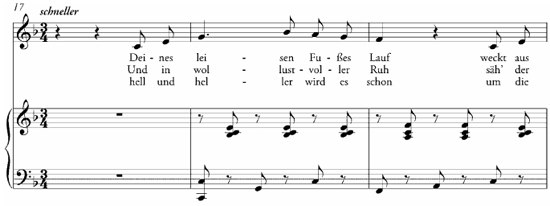

Example 7.1 Bettina von Arnim, ‘An Luna’

The cyclic nature of the story is picked up by Bettina in her setting of ‘An Luna’, where the opening accompaniment is harmonically static. The almost constant use of the dominant seventh chord removes any feeling of climax and repose. Even the ending is open, hovering about the dominant. Despite the harmonic stasis, however, ‘An Luna’ is tonally ambiguous. Because there is no introduction and no postlude, the ambiguity of the final chord of each verse blurs the strophic boundaries until the very end, when the questioning half-close becomes at last apparent. This continuous feel makes the music almost glide, and the rests in both voice and piano seem a particularly poignant cessation of movement. Bettina also, through irregular rhythmic movement, blurs where text lines begin and end. The accompaniment is deliberately neutral, a framing device that is representational of the ‘larger context’ that is the performance space for the emotional improvisation of the singer. The text dictates the structure: therefore we cannot define structure in the usual musically analytical terms. It is as if all the accepted defining components have been removed – harmonic direction, formal symmetry – so that we are left with what is, in a sense, a return to the original lyric. In her music, Bettina has created a bridge between listener and text, thereby enabling our access to artistic experience in a way that has been seen historically as inherent to the role of muse. If we accept this as a definition of muse, Bettina has been successful in her aims.

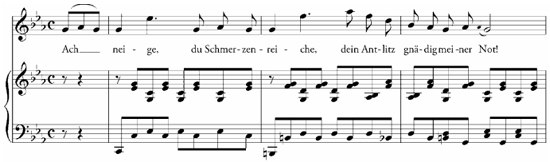

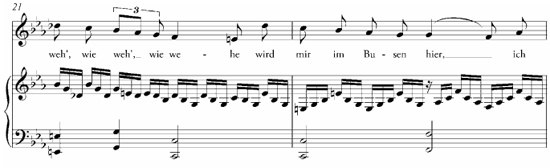

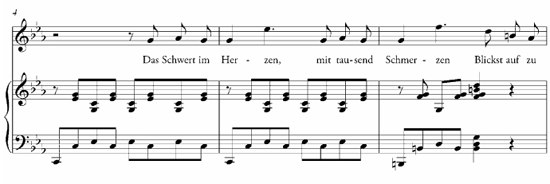

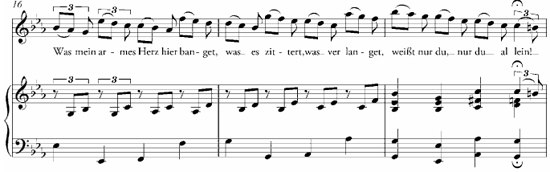

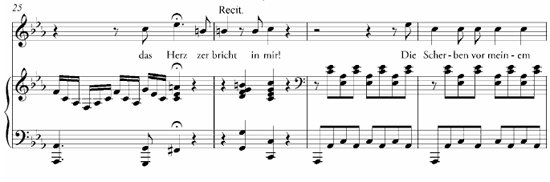

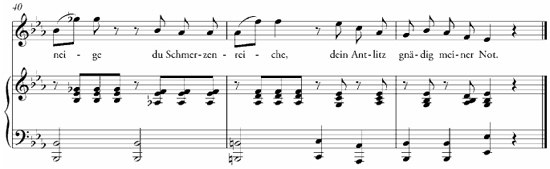

The other song, ‘Ach Neige’ 23(example 7.2) raises a different set of questions, but again, Bettina’s musical language could be seen to arise from her belief in cyclic creativity. Bettina did not want to set all of Faust, but she did write an Overture – one of the only two textless compositions she is known to have written. Unfortunately this is, at present, lost, along with settings of ‘Was ist die Himmelsfreud’ in ihren Armen’, ‘Der König von Thule’, and two songs known only as ‘Zwei glückliche Melodien zum Faust’. One of these ‘good melodies’ may be the setting of Faust’s declaration of love to Gretchen in the garden, ‘Ich schaud’re nicht’, which appears in the Spontini collection. It is interesting that Bettina chose to set direct speech from Faust, as well as some of the more obvious songs.

Example 7.2 Bettina von Arnim, ‘Ach neige, du Schmerzenreiche’

While writing ‘Ach Neige’, Arnim wrote to Goethe, ‘ich meine es müßte gut sein denn es hat mich innig gerührt.’24 She also told her husband, ‘Mein Lied […] hat mich viel Mühe gekostet.’ 25 Formally, the song is a mixture of linear development and sectional compartmentalization. It has the effect of introducing what Ruth Solie has called ‘narrative gaps’. Not only is each section an immediate response to a changing emotional context, the listener also has the impression that we are within a larger story, that other history and experience are implicit in the breaks. The space that is thus constructed is not so much a performance space, as in the case of ‘An Luna’, but rather a narrative space. This narrativity, however, is more flexible than it may at first appear. We are accustomed to an Ariadne’s thread of chronology, in which structural events conform to a linear, conscious time, occuring in logical response to textual and musical material. But ‘Ach Neige’ seems to follow a circular, subjective time, in which, as in the subconscious, all events are concurrent and present. This can result in musical language that is ‘incorrect’ under the rules of mainstream response. The odd intrusion of major tonality at the end of bar 2 is one example. C minor has barely been established before two fleeting beats of the relative major interrupt, only for C minor to close over again instantly. (See example 7.2, bars 1 to 3.) This moment of warmth could be seen as an almost physical presence of the person whom Gretchen addresses, and would thus be an overlapping chronology, a reminder that this is not simply Gretchen’s tale. The same effect seems to be in place at the end of the section, when Bettina chooses to highlight rhythmically the word ‘deine’, in sein’ and deine Not’ (bars 9 to 11). We are taken back into an earlier time frame and forced to remember that Gretchen speaks to Mary, who in some ways mirrors her. In the same way, there are moments that project the listeners forward – the sudden unison accompaniment at ‘deines Sohnes Tod’ seems autobiographical in its maternal empathy (bars 4 to 7). The very ending, too, with its major tonality (bars 38 to 42), involves us in an implicit assumption of our fore-knowledge of Gretchen’s redemption. Gretchen is not aware of this, but we know of her rebirth as the Ewig-Weibliche, creative source.

Despite Bettina’s unconventionality as composer, or perhaps because of it, she can reveal a richer font of creativity than may be at first apparent. Her goals seem to have been not so much to produce repertoire, but to open up new routes and new directions through her discourse with other creators. Suzi Gablik sums up this partnership in art when she writes:

when art is rooted in the responsive heart, rather than the disembodied eye, it may even come to be seen, not as the solitary process it has been since the Renaissance, but as something we do with others.26

Footnotes

1 Bettina von Arnim, Goethes Briefwechsel mit einem Kinde, in Sämtliche Werke, ed. Waldemar Oehlke (Berlin, 1920-22), III, unpaginated. ‘you should ignore the prejudice of those, who before they are acquainted with the book, condemn it as not genuine and thus deceive themselves of the truth.’

2 Quoted in Ann Willison Lemke, Bettine’s Song: The Musical Voice of Bettine von Arnim, neé Brentano (diss., Indiana University, 1998), p.154. ‘I do not speak of [Goethe], I speak to him.’

3 Kimberley Marshall, ed., Rediscovering the Muses: Women’s Musical Traditions (Boston, 1993), p.xix.

4 Ferdinand Comte, The Wordsworth Dictionary of Mythology (Ware, 1994), p.135

5 Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, Dichtung und Wahrheit (Stuttgart, 1884), p.445. ‘She was the most wonderful woman, and I know of no other who can compare with her.’

6 Lemke, op.cit., p.1.

7 Arnim, op.cit., IV, p.149.

8 Bettina von Arnim, Goethes Briefwechsel mit einem Kinde, op.cit. See for example the letters dated Winkel 7. August, pp259-263, and 24. July, pp.232-34.

9 Riane Eisler and Alfonso Montuori, ‘Creativity, Society and the Hidden Subtext of Gender: Toward a New Contextualized Approach’, forthcoming in Social Creativity eds A. Montuori and R. Purser (Hampton Press:Creskill, NJ), III.

10 Bettina von Arnim, Werke und Briefe (Frechen, 1963), IV, p.125.

11 Gert Mattenklott, ‘Romantische Frauenkultur: Bettina von Arnim zum Beispiel’, in: Frauenliteraturgeschichte: Schreibende Frauen vom Mittelalter bis zur Gegenwart, eds Hiltrud Gnüg and Renate Möhrmann (Stuttgart, 1985), p.123.

12 Quoted in Lemke, p.31. ‘My teachers say that I’m not stupid, and that although I understand many things better than a man, it will be a long long time before I can do anything as well as a man can.’

13 Bettina von Arnim, Sämtliche Werke, III, p.6. ‘Now guess what the tailor is making for me. An Adrian? No! – A Paduasoy? No! – A Boddire? No! – A Mantilla? No! – A training-gown? No! – A Pair of trousers? Yes! – Hurrah! (Other times are now coming) – and a waistcoat and coat too. Tomorrow everything will be tried on; it must set well, for I have ordered everything to be made full and easy; and then I throw myself into a chaise, and courier-like travel day and night through the entire armies, between friend and foe […]’ Translation from Bettina von Arnim, Goethe’s Correspondence with a Child (London, 1837-39).

14 Quoted in Lemke, p.48. ‘the be-all and end-all for the wife, but for the husband it is simply an epoch.’

15 Sally A. Winkle, Woman as Bourgeois Ideal: A Study of Sophie von la Roche’s ‘Geschichte des Fräuleins von Sternheim’ and Goethe’s ‘Werther’ (New York, 1988) p.95

16 Arnim, Sämtliche Werke, III, p.235. ‘she had one at her breast, the other she rocked rhythmically with her foot while she sang her song.’

17 Quoted in Bettina Brand, Komponistinnen in Berlin (Berlin, 1987), p.32. ‘Ich hab oft darüber gedacht, daß Musik so leicht und gleichsam von selbst sich melodisch ins Metrum füge, die doch vom Verstand weit weniger erfaßt und regiert wird wie der Sprache, die nie ohne Anstrengung das Metrum des Gedankens ergründet und entwickelt.’ I have often thought how music, which fits so naturally and melodically into the metre, is less easily grasped and governed by the intellect; just as language can never, without effort, be fathomed and developed by thought.

18 Bettina von Arnim, Ein Lesebuch, ed. by Christa Bürger and Birgit Diffenbach (Stuttgart, 1987), p.45. ‘Now it gives me a great deal of joy to compose – hymns to Diana, paens of praise of Dionysos, translated by Stolberg. Oh yes, it gives me so much joy. In the evening I climb up onto the roof from the laundry, there I invent the most wonderful idioms. The sky blushes with deep empathy, and the stars gather round and listen, and Hoffmann listens too – he is our closest neighbour. My voice carries, if only my spirit did as well! Hoffmann comes to the lesson the next morning; he already knows my melody half from memory – the part I had written down in pencil he knew better than I. We scarcely argued about the timing, because he wanted the whole thing to be as I had originally sung it; the beats and upbeats are of lesser importance and make the established rules irrelevant. He says, if I apply myself to my studies, then music may break new ground. Foolish fellow! He compliments me so that I’m motivated to learn; I know that he says these things to keep my enthusiasm at the very highest pitch!’

19 M. Daniell Ollivier, ed. Correspondance de Liszt et de la Comtesse D’Agoult 1840-1864, (Paris, 1934), p.321. ‘Those songs that she has just published and dedicated to Spontini are of no great value.’

20 Max Friedländer, in Arnim, Sämtliche Werke, IV, p.299. ‘A pleasant talent for an amateur.’

21 At the time, Spontini had been accused of offending the king and booed out of the opera house. Bettina’s dedication was at once a political statement and a gesture of support.

22 Ann Willison Lemke, ed., Von Goethe inspiriert, (Kassel, 1999), p.12.

23 Ed. Renate Moering, Von Goethe inspiriert (Kassel, 1999).

24 Quoted in Lemke, Von Goethe inspiriert, p.56. ‘I think it must be good, because it has moved me deeply.’

25 ibid., p.56. ‘My Lied […] has cost me great effort.’

26 Gablik, Suzi, ‘Making Art as if the World Mattered’, Utne Reader, 34 (1989), p.76.