Our theme is a city—a great Southern importing, exporting, and manufacturing city . . . where we can . . . open facilities for direct communication with foreign countries, and establish all those collateral sources of wealth, utility, and adornment, which are the usual concomitants of a metropolis. . . . Without a city of this kind, the South can never develop her commercial resources nor attain that eminent position to which those vast resources would otherwise exalt her.1

In The Impending Crisis of the South, an influential attack on slavery published in 1857, Hinton Helper asserted that the South’s lack of a “great” city blocked economic development and denied it international prestige. Helper’s criticism reflected his experience in cities, Northern and Southern. Raised in central North Carolina towns by middle-class manufacturers, Helper clerked at the store of a slaveholding planter/industrialist. In 1850, Gold Rush tales lured Helper west via New York and other free-state cities, where he saw poor men enjoy opportunities unavailable back home. Helper was prevented from including this observation in a book about his travels because his publisher feared offending Southern readers. Infuriated, Helper wrote his full-length indictment of slavery while living in Baltimore, Maryland, the South’s largest city. There he witnessed proslavery mobbing of Republican Party meetings, even as city manufacturers seemingly vindicated Republican free-labor ideas by employing over 17,000 wage workers but almost no slaves, whose local presence was fading. The latter trend convinced Helper that among Southern cities Baltimore was “greatest because freest” from slavery’s “pestilential atmosphere” within which “an aspect of most melancholy inactivity and dilapidation broods over every city and town.”2 Notwithstanding this observation, Helper’s own life, which included patronage from a modernizing slaveholder and experience in a proslavery industrial port, suggests that the urban South did, in fact, possess the “usual concomitants of a metropolis” but in a form that Helper and sympathetic readers disliked.

A “great city,” as Helper understood it, was measured by the giant metropoles of his day, New York and London, and their example continues to influence interpretations of Old South urbanization. While urbanization had other features, the North and England were clearly ahead of the South in urban population, a basic measurement of city building. In 1860, the North possessed thirty-four cities with more than 20,000 residents, while the South had only eleven; one in four Northerners lived in a community of more than 2,500 people (the U.S. census definition of urban) compared to only one in ten Southerners; and the largest Northern city was five times the size of the largest Southern one. England was even farther ahead. In 1850, it had become majority urban and had ten times the South’s urban population, a number that London alone doubled.3

To explain the South’s lower proportion of urban residence, historians have followed Helper in portraying Southern cities as stunted versions of the modern metropolitan centers that transformed the North. For example, David Goldfield regards the South as “part of the modern urban nation,” but a lesser one that, because of rural folkways and slaveholder economics, “by 1860 . . . was lagging farther behind northern urbanization than at any previous time American history.” These arguments work from a developmental model of social history that posits growth from infancy to maturity. Applied to cities, societies travel the same road from rural to urban but some move faster than others. Accordingly, slavery acted as a “handicap” on the South that caused it to lag behind the North in urban modernity.4

This scholarship mischaracterizes antebellum Southern urban history as either opposed to change or trailing behind more advanced societies. At issue is urbanization, a flexible historical process that does not treat commercial-industrial metropoles like New York and London as the essential measure of a city. Urbanization refers to a proportional increase in the urban-over-rural population and qualitative change within cities marked by “differentiation, standardization, [and] change in the quality of social relations. . . .” City growth promotes innovation and fosters urban trade networks of goods, information, and people—changes that, in turn, promote “relationships that cross the boundaries of kinship, locality, and traditional alliances.”5 Conceiving of the slave states as lagging behind the North loses sight of the ways that the Old South met the standards of urbanization but did so on terms that suited its commitment to slavery. That perspective can be lost if the urban South is considered solely in comparison to standards of city size and industrial output set by the eastern Northern states and England. Southern cities were smaller than Northern ones, but by the same token Northern cities were smaller than those in other parts of the world. For example, mid-nineteenth-century New York is rarely characterized as a less-modern version of Beijing, even though the latter had 60 percent more people than the former. To understand how Old South city-building was caught up in the currents of modernity, this essay makes comparisons beyond the North and looks anew at the differences slavery made for urbanization.

Southern cities grew rapidly, combined industry and trade, built railroads and telegraphs, attracted a heterogeneous population, standardized public spaces, and allowed for social mobility and political openness. Yet each of these steps bore the marks of slavery. The results were something different than an immature version of the North and England. By comparison, Southern urbanites typically lived in bigger cities. And their cities were more comprehensively policed, and more culturally diverse. On the other hand, Southern cities had less industry, less democracy, and fewer public services than their free-labor peers. For someone like Helper, who hated slavery and valued political openness, the urban North was a better place. However, to say—as Helper and like-minded observers did—that Northern cities were also more modern ignores the features of Old South urbanization that worked their way into the fabric of post–Civil War cities, Rather than a retrograde stage of urbanization, antebellum Southern cities represented one of several ways that the forces of population growth, communications revolution, and mass production remade urban life in the nineteenth century.

How Fast and How Many?

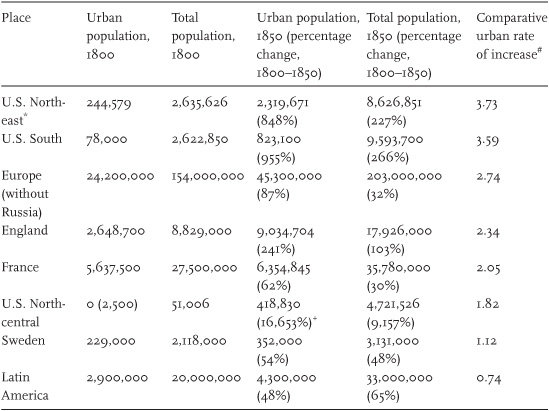

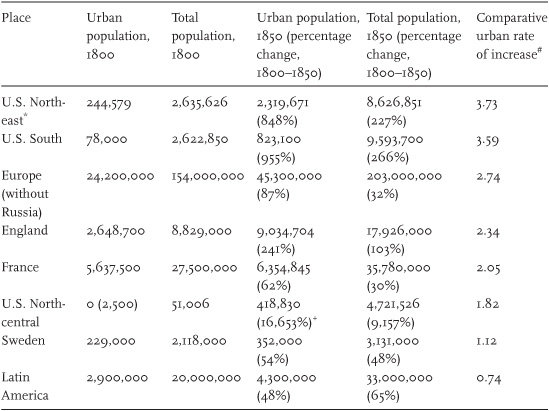

Judged by the rate of urban population growth, the antebellum South stood in the vanguard of its contemporaries in the Americas and Europe. To measure the rate of net urbanization—how much faster cities grew than rural places—the comparative rate of urban increase divides growth rates for cities and towns by the total population’s rate of change. This method corrects the distortion of fast growth rates for societies with few city dwellers by measuring urban change against a society’s total population change.6 As shown in table 7.1, the Old South stood just behind the northeastern United States in net urbanization. Although the South was still overwhelmingly rural in 1850, its quickening city growth, which steadily gave cities more people and prominence in Southern life, put it in the camp of urbanizers like the North-east states and England.

TABLE 7.1. Comparative rates of urban increase, 1800–1850.

Source: Data comes from Paul Bairoch, Cities and Economic Development: From the Dawn of History to the Present (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1991), 423; John M. Merriman, ed., French Cities in the Nineteenth Century, (London: Hutchinson, 1982), 14; Andrew Lees and Lynn Hollen Lees, Cities and the Making of Modern Europe, 1750–1914 (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2007), 5; David B. Grigg, Population Growth and Agrarian Change: An Historical Perspective (New York: Cambridge University Press, 1980), 169, 226. Lower limit of U.S. urban is 2,500 people; Europe, 2,000; Latin America, 5,000.

Note: For method see Jan De Vries, “Problems in the Measurement, Description, and Analysis of Historical Urbanization,” in Urbanization in History: A Process of Dynamic Interactions ed. Ad van der Woude, Akira Hayami, and Jan De Vries (New York: Oxford University Press, 1995), 47; Leonard P. Curry, “Urbanization and Urbanism in the Old South: A Comparative View,” Journal of Southern History 40 (February 1974): 50.

# The comparative rate of urban increase is determined by dividing the rate of change for the urban population by the rate of change for the total population.

* The Pennsylvania-Ohio border divides North-east from North-central. Pacific Coast states excluded. U.S. Northeast states include Connecticut, Maine, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, New Jersey, New York, Pennsylvania, Rhode Island, and Vermont. U.S. North-central states include Illinois, Indiana, Iowa, Michigan, Minnesota, Ohio, and Wisconsin.

+ Because North-central’s 1800 urban population is zero, it cannot be divided into the 1850 regional urban population. Therefore, the equivalent of the minimum urban unit, 2,500 people, is used as a stand-in for zero. Showing the proximity of that number to the actual early republic population of the North-central states, in the 1810 federal census their total urban population was 2,540.

The rapidly urbanizing South differed fundamentally from other highly rural societies like Sweden or Latin America that experienced static or declining net urbanization. The rural character of these societies signified continuity with a predominantly rural past. In the South, the comparatively small share of urbanites in its mid-century population belied a demographic transition from country to city that broke with the region’s eighteenth-century past. The South’s higher rate of urban growth as a percent of total population growth also diverged from the North-central states, where the boom in agriculture made rural population rise at a pace more in balance with their impressive urban increase. As time passed residents of each section of the nation would find the other’s pattern of city building disturbingly unlike their own experience.

During a steamboat passage from Cairo, Illinois, to New Orleans in 1857, Alabama-bred writer Daniel Hundley met “an old gentleman from New-York” habituated to his city’s “continuous hum and noise.” Traveling southward, the man grew so agitated by the “vast solitude” of the lower Mississippi River that he burst out “WHERE’S YOUR TOWNS?”7 This question reflected how differently urbanization in the slave states appeared to a resident of the free states. While the South’s growth rates resembled those of the North-east and England, its distribution of urbanites between large cities and smaller towns better resembled a Latin American slave society. The North as a whole and England stood out not only for New York and London but also for their numerous smaller towns. In 1851, England’s vast urban edifice included 563 places of 5,000 or more people, and instead of London “the typical British urban dweller lived in a small town.”8 Meanwhile, the typical Southern urbanite lived in a city of at least 20,000, an experience more familiar to residents of other New World slave societies.

The share of urbanites living in large cities, for which comparable data are available, stands in as a measure of town-to-city ratios. In 1860, 65 percent of urban Southerners lived in the section’s ten largest cities.9 Outside the South, the ten largest U.S. cities had many more residents, but they accounted for only half of the non-Southern urban population. The North’s lower concentration of big-city residents resembled the pattern for other Atlantic rim nations that lacked slavery, such as Sweden (49 percent), England (40 percent), and France (39 percent). Furthermore, urban population dispersal looked alike in free societies that urbanized rapidly, like the North, or slowly, as did Sweden. Only the sugar-planting, slave island of Cuba, with three-fourths of its urban population resident in large cities, surpassed the South.10

The importance of property rights in slaves helps explain the South’s cities-without-towns pattern of urbanization. Contrasting the investment strategies of Northern “landlords” and Southern slaveholding “laborlords,” Gavin Wright shows how Northern town building met the needs of land promoters who had to provide public amenities such as roads, schools, and markets to attract laborers who would buy land. Slaveholders, on the other hand, had the capital and coercive power to take their labor to new plantations. Having invested in labor and land instead of land by itself, slaveholders did not need the towns that free workers demanded.11

Although slaves were more concentrated in the lower South, slavery’s negative impact on town building was evident everywhere that the institution was legal. In 1824, a British traveler wrote that “in New York . . . villages were rising up in various places. . . . But in Virginia how dismal was the look of things! Few, very few villages attracted the eye. From Richmond to Charlottesville, a distance of eighty miles, there was hardly one deserving the name. . . .”12 A decade later, aboard an Ohio River boat, Frenchman Alexis de Tocqueville noticed “the population is sparse” in slave Kentucky, while “the confused hum emanating from the right bank [in free Ohio] proclaims from afar the presence of industry.”13 Like Hundley’s associate, free-labor visitors’ equation of few towns with failed urbanization reveals more about expectations derived from their homelands than about the South, where urban dwellers were more likely to live in cities.

Because Ohio had many more people than Kentucky, a more telling test of Tocqueville’s riverboat observation is Indiana, another of Kentucky’s free-state neighbors. In 1860 these states had nearly the same size and percentage of urban residents but very different distributions of cities and towns. Villages of a few hundred to 2,500 people littered Indiana but were scarce in Kentucky, whereas Kentucky doubled Indiana’s population in cities of 10,000 or more. Arguably, concentration in cities gave Kentucky urbanites a more cosmopolitan experience than did the diffusion of Hoosiers in towns.

The same trend held for the sections at large. As the size of the urban unit increased, the South narrowed its gap with the North. In 1860, the ratio of Northerners to Southerners living in towns of less than 2,500 people was 6:1; for places of 2,500 or more, the ratio fell to 4:1; and for cities over 20,000, it dropped to 3:1. At no point did the South achieve parity with the North, but it got closer near the top of the urban scale. As discussed below, slavery as practiced in the highly commercialized economy of the Old South stimulated urban growth—but a particular kind that favored cities over towns. What appeared to free-labor observers as a sign of social decay was, in fact, a different kind of urbanization, one in which cities shot up without a network of small towns, much like tree trunks without branches.14 Notwithstanding explanations of the comparative lack of towns in the antebellum South as products of a rural mind-set or poor soils, the rapid growth of towns after slavery ended strongly indicates that the labor laws of the Old South more than anything else shaped its path to building modern cities.15

Significantly, the Southern subregion with the most pronounced cities-without-towns growth pattern, the seven cotton-growing states of the lower South, also had the highest share of slaves (one-half) in its rural population. In 1860, the lower South housed a smaller proportion of the South’s small-town residents (one-fourth) than of its 20,000-plus city dwellers (one-third), and it had a higher rate of urban residence than the upper South states of Arkansas, North Carolina, Tennessee, and Virginia, despite having fewer towns proportional to population. In Georgia, small towns dotted small-farming Piedmont counties, but in “the coastal savannahs and swamps of the southeast, villages were relatively few.” Not surprisingly, “the latter area boasted the highest concentration of slaves in the state and the greatest commitment to commercial agriculture.”16 Rather than an innate antiurbanism, the scarcity of Southern towns was a symptom, or expression, of the ways that slavery influenced land-development strategies. As explained above, slaveholding planters—the wealthiest rural Southerners—had less incentive than Northern land speculators to invest in town-building public works aimed at attracting free labor to their lands. Furthermore, enslaved workers were less able to stimulate town growth than were free workers because slaves were not paid a wage and therefore had less cash to spend in local stores, which were the primary economic enterprise in most small towns.

Cities in Society: Urban Networks

In addition to implying failed urbanization, the South’s comparative absence of towns also informs the argument that “no southern system of cities developed” and that the urban South was a “‘colonial’ outlier of the northeastern regional city-system.”17 Sometimes called “urban network,” city-systems refer to connections that cities share with one another. Like comparisons of city size, the “colonial outlier” assessment of the South’s city-system captures a real difference between the sections. The North had a denser urban network that in many respects, particularly international trade, subordinated the South to its primary city, New York. Nevertheless, concluding from these facts that the South either lacked an urban network or relied on New York to mediate between its cities hides connections that bound Southern urbanites to one another and to the wider urban world.

The South’s urban networks are hard to see if viewed through a theoretical framework that treats large-scale manufacturing as an essential component of modern city-systems. Formulated during modernization theory’s heyday in the Cold War era, the classic city-system model regarded industrial innovations, like improved plows, as catalysts that “released” capital and labor from agriculture and redirected them to cities possessing an “agglomeration” of factors necessary for further production. Cities that cross a resource “threshold” experienced an industrial “takeoff” that compounded into additional growth and drew smaller urban places into their network.18

As critics note, however, flows of investment capital—the driver behind factories and commerce—are only one of many exchanges between cities. Movements of labor, ideas, and political power do not always coincide with capital flows because “networks are always partial and cannot, and are not, simply mapped straight onto a messy and complex world.”19 For example, New Orleans was subordinate to New York City in global cotton commerce and in intellectual life, but it was the center of the domestic slave trade and, along with Richmond and Charleston, a leader in the genre of proslavery polemics.

Furthermore, industry was not a prerequisite for building cities and towns. Europe’s first net increase in urban populations occurred in Britain and the Netherlands in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, before the factory system came to dominate either country. Instead of being caused by industry, urban growth responded to a change in rural culture that went from seeking only subsistence to a new consumerism that created demand for more goods. This change, which occurred independent of labor-saving technology like better plows, created more jobs in cities to meet rural demand. “Only in a fully developed market economy with country dwellers strongly conscious of a desire to acquire urban goods and services,” writes E. A. Wrigley, “were there the kinds of incentives to improve agricultural practices that could underwrite urban growth by providing the flow of food for people and organic raw materials for industry.” In short, the country had to change before the city could grow.20 This pattern of rural consumption driving the expansion of cities and towns held for the antebellum South, but slavery altered the pattern from the free-labor archetype.

To explain that pattern: After the 1750s, planters in the Southern colonies raised their personal consumption, which aided urban growth.21 Thereafter rural Southerners’ consumer demand sufficiently exceeded the level of subsistence to make cities grow. Not only did planters buy luxuries like books, clocks, and fine clothing, but recent studies demonstrate that even in areas with bad soils and transportation, like Appalachia, small farmers concentrated on cash crops and avidly bought town goods.22 As Larry Hudson shows in this volume, slaves participated in the market,23 but bondage restricted the amount of cash they could spend and barred them from urban amenities like schools and banks, thereby diminishing rural resources for small-town development. The South urbanized in a heavily commercialized slave society, where the limits on slave labor’s ability to purchase urban goods and services kept the region’s rate of urbanization below that of the northeast, where free farm labor had more disposable income. For the same reason, the South’s urban growth rate fell behind the North-central states in the 1820s, when improved transportation and a steady influx of farmers boosted the role of marketing and manufacturing in North-central cities.24

Slavery’s impact on consumption also manifested itself in the behavior of planters, which favored the development of a few cities over numerous small towns. In the village of Gallatin, Mississippi, merchant Samuel Aby built a thriving business with local cotton growers but moved to New Orleans when a proposed “Rail Road from N. O. to Jackson” threatened to bypass Gallatin and “ruin our trade here.” Confident that his “great many friends amongst the planters . . . will doubtless transact all their business in N. Orleans through him,” Aby retained rural customers who preferred long-distance shipping rather than buying direct at the cost of building up Gallatin, which never registered enough population to appear in antebellum census records.25

On top of cutting costs, moving to a major port improved Aby’s access to new trends and products preferred by wealthy country consumers. More generally, cities connected Southerners to goods, people, and ideas from around the world. Leading merchants, editors, booksellers, and authors clustered in cities, as did theater troupes, visual artists, and architects. City dwellers discussed the ideas generated by these professionals in lyceums and debating societies that fed what one historian calls the “desire to rethink southern ideas and institutions.”26 To better experience these cosmopolitan trends, planters often maintained dual residences in town and country. Illustrating these plantation-city ties, in 1850 John Rutherfoord, who lived in Richmond, wrote to his father, a politician running the family estate in the Virginia Piedmont, to convey news about state government, promise to fulfill his father’s request for “the best buggy that Richmond can furnish,” and criticize “the lonely and dreary life you lead in the country. . . .”27 The Rutherfoords’ links to Richmond typified a rural relationship to urban services that favored cities over small towns because cities had a much higher density of the commercial and cultural amenities that planters desired.

The Rutherfoords’ correspondence hints dually at an identification with a universalist cosmopolitanism—that is, rather than get by with local gossip and handicrafts, they wanted the news and the goods of the world—and a rootedness in the particular setting of the slave South. This dual perspective found expression in a description of English cities written in 1853 by William Henry Trescot, an American diplomat from Charleston, South Carolina. Corresponding to his wife about London, Trescot exclaimed “what magnificent streets and buildings! Nothing however, strikes me as strange—even the soldiers seem like so many militia companies on parade—with a difference.” Although that passage did not elaborate the “difference,” Trescot generally approved of the contrast between London and his home. He praised the “abundance of room for light air” in public squares, the “superb avenues and room for thousands not to crowd each other,” and went so far as to call London “the perfection of this world’s civilization.” Yet Trescott did not want to stay there. Like many Americans abroad, he felt shut out of London’s social life, which he described as “nearly always frivolous and often vicious.” Moreover, as a slaveholder dedicated to white supremacy, Trescot was unnerved by London’s blurring of racial boundaries. He expressed less surprise at his hosts’ antislavery opinions—Americans were well aware of British abolitionism—than at their respectful treatment of persons of African descent. This discomfort was manifest in Trescot’s account of a visit to the U.S. embassy by Liberian President Joseph Jenkins Roberts, who, like many of Liberia’s elite, was a free black immigrant from the United States. Trescot described Roberts as “the most elaborately dressed man I have seen in London” who, in response to white “servants bowing very politely,” carried himself “with a dignified complacency.” Of all the sights London had to offer, it was the ability of Roberts, a black man who might have been attacked for a similar display in his Virginia birthplace, to be treated as an equal in elite circles that left Trescot “standing in gaping wonderment.” In London, Trescot recognized improvements on familiar features of his native Charleston, but he also identified differences that provoked him to assert his affiliation with a separate, unique country and section, one ultimately defined by the practice of racial slavery. Many urban Southerners shared this defense of distinctiveness, but they, like Trescot, also reveled in their connections with the cities of the world.28

Perhaps the best illustration of the ways that Southern urban networks went beyond the nation’s borders is immigration. In 1860, 34 percent of people in Southern cities of 20,000 or more were born abroad as compared to 39 percent in comparable Northern places. However, the higher percentage of blacks in the urban South (15 percent) than the North (2 percent) meant that immigrants comprised the same share of whites (two-fifths) in each section’s cities. The urban South had a smaller proportion of native-born whites (51 percent) than the urban North (59 percent); of those, 10–15 percent were Northern migrants, such that a majority of whites hailed from outside the slave states. By these demographics the urban South was more culturally diverse than the urban North and much more so than contemporary London, where the largest immigrant contingent, the nearby Irish, accounted for only 4.6 percent of its people. The urban South’s cultural pluralism not only confounds another measure of its supposed lag behind the North, it also reveals the intercity networks that slave states shared with foreign ports.29

If Southern cities’ interconnections and industry seem weak compared to the North, a comparison with Latin America throws into relief the basic strength of Southern city building. Although not the prime cause of initial city growth, manufacturing usually increased along with urban networks. In 1860 the U.S. South achieved levels of industrial production three and four times above what Brazil mustered a quarter-century later. Most Southern industry was urban, and all Southern cities had growing manufacturing sectors. In railroad track, which connected cities, the South dwarfed the almost nonexistent networks of Brazil and Argentina: In 1860, Southern tracks totaled 9,165 miles, which connected the region’s major cities to each other across vast distances; Brazil had only 70 miles. Likewise, in 1855, the Argentine capital of Buenos Aires was fed by only 6 miles of track.30

Latin American cities’ weak links to the countryside owed much to “the tendency for export production to be based on relatively self-sufficient economies within plantations, haciendas, or mines,” which soaked up rural demand that spurred urbanization in the non-self-sufficient rural South.31 Contrasting rural mind-sets in his 1853 history of Mexico, Baltimore’s Brantz Mayer wrote that “the planter . . . is usually in our own country to be envied for the peculiar privileges which his station affords him. But in Mexico, the position and education of the planter . . . are altogether different from those of the North American . . .,” because, among other reasons, hacendados did not “enjoy equal facilities of intercommunication between the cities or rural districts of Mexico.”32 Along with very weak rural demand, the below-subsistence wages paid in some Latin American cities curtailed consumption in the towns themselves. After Ecuador’s separation from Spain in 1820, investors in the port of Guayaquil tried to manufacture for local customers only to find that “the poor were unable to buy even tobacco.” By comparison, markets and consumerism were more pervasive in the rural Old South; as a result, the slave states had faster growing and more densely networked cities.33

Some Latin American cities succeeded in creating strong urban networks. For example, Havana, Cuba, which rivaled Baltimore’s Civil War–era population, completed Latin America’s first railroad in 1838, adopted the telegraph in 1851, and hosted a thriving tobacco industry that employed over 15,000 workers. Of course, Cuba, like the U.S. South, was a slave society, and the two “shared markets, technologies, and a bedrock reliance on a coercive labor system marked by brutality.”34 Cities in Cuba and the U.S. South grew faster than their countrysides because of well-developed urban networks that supplied rural consumer demand. Similarly, both places differed from the pattern of free-labor urbanization by concentrating urban dwellers in cities at the expense of towns. Understood in a global comparative context, the Old South built urban networks typical of commercialized slave societies.

Could Slavery Survive without Cities?

Although slavery did not prevent urbanization, slaves’ presence in large cities was declining. Between 1840 and 1860, the South’s ten largest cities added nearly half a million whites but almost no slaves, lowering the proportion of slaves from 19 to 8 percent of the total population. In his chapter in this volume, Marc Egnal regards this proportional decline as evidence of the “weakening grip of slavery on the Southern cities.” This trend and Egnal’s counterpoint raise an important question about Old South urbanization: could slavery survive in its growing cities? Historian Richard Wade answered in the negative by exploring how urban life’s everyday freedoms acted like “corrosive acids” on slave discipline. For Wade and others, “the cause of slavery’s difficulty in the city was the nature of urban society itself.”35 Unquestionably, cities challenged slaveholder authority, but few have asked this question in reverse: could the South’s version of chattel slavery have survived without cities? An overview of the topic suggests that the answer is no.

Cities played a “crucial role” in the slave trade that sold one million bond-people from the seaboard states to the southwest and approximately two million more within state lines.36 Urban places offered slave traders access to credit from banks, security from jails, food and clothing (as well as whips and chains) from provisioners, and, most of all, markets and customers. One-time slave Frederick Douglass thought his move from country to city “opened the gateway” to freedom, but for countless others going to town brought one of slavery’s worst features: forced separation from family. Recalling the sale of “little Joe, the cook’s son,” Elizabeth Keckley, a slave in southern Virginia, wrote that “his mother was kept in ignorance of the transaction, but her suspicions were aroused. When her son started for Petersburg in the wagon, the truth began to dawn upon her mind, and she pleaded piteously that her boy should not be taken from her.”37

If transported to a county seat, slaves waited in jail for shipment or sale. In cities they went to “depots” and auction houses operated by traders, often, as in Richmond, a short walk from the principal hotels and businesses.38 In their campaign to outlaw slave sales in Washington, D.C., which occurred within sight of the capitol, antislavery Northerners protested a commonplace feature of the urban South that generated outsized profits. On the eve of the Civil War, slave sales amounted to $8 million for New Orleans, $4 million each for Charleston and Richmond, and $2 million for Natchez, Mississippi, which had only 6,000 residents.39

The slave trade also used the South’s urban network to direct the flow of interstate traffic following the cotton boom. Trading networks moved human cargo between Lexington and Louisville in Kentucky to Memphis and Natchez on the lower Mississippi, and from Alexandria, Danville, and Norfolk on Virginia’s Chesapeake coast to the ports of the lower South and New Orleans. Border South towns, even those with few slaves, were vital sale and shipment points. In St. Joseph’s, Missouri, perched on slavery’s northwestern frontier and home to only 170 slaves out of 8,932 people, English immigrant Elise Isely remembered seeing “a negro woman sold from a scaffolding built beside the street. . . . Right past my uncle’s house drove the slaver, while the woman screamed in bitterest anguish.”40 Similarly, Wheeling, Virginia, which had only forty-four slaves in 1850, “grew into a major regional slave-trading hub” because of its location at the northernmost point where slaves could be traded legally on the Ohio River, and hence the entire Mississippi watercourse.41 In the 1850s the slave population of the four border states increased by 10 percent, notwithstanding mass sales southward. Even if border cities themselves had few enslaved residents, slave traders needed them to conduct commerce in human chattels.

In a role analogous to a research-and-development laboratory for slave-holders, cities spawned most of the adaptations cited as keys to slavery’s chances for persisting past 1865 had the Civil War not intervened. The practice of slave hiring—that is, leasing a slave to an employer for a fixed period—began in Charleston, South Carolina, in the first half of the eighteenth century, as local masters sought to maximize profits by meeting rising demand for domestic service and artisan labor. The Chesapeake region adopted hiring only after its towns grew in the late 1700s. Along with hiring, urban masters pioneered “term slavery,” whereby slaves exchanged work and cash for postdated manumission.42

Factory slave labor occurred in cities because unlike mining and lumbering, only cities had the agglomeration of capital, markets, and service that mass production required. As James Huston argues, the comparatively small number of enslaved industrial workers owed more to wage rates than to problems of factory discipline. If cotton prices fell, the tobacco mills of Petersburg and iron foundries of Richmond offered slaveholders ready prototypes for making factory hands of field workers.43

Increases in slave hiring, dangerous industrial work, and rising slave prices spurred another urban innovation: slave life insurance. On an 1851 visit to Richmond, a British traveler noted that “a good man will fetch $800. Some I saw had been hired at seventy-five dollars a year, and are therefore generally a very good investment.” The increasing profits of urban slavery encouraged owners to insure hired slaves’ lives against risky industrial work. A recent study finds that “the proportion of life insurance policies on the lives of urban slaves in the Upper South approximated that of white male northeasterners by the mid-1850s.” Significantly, the pioneering firm in slave insurance was headquartered in Baltimore, the South’s most industrial city and an early site for slave hiring.44

The problem of urban slave discipline, often cited as the reason that cities undermined slavery, prompted the South’s early development of paid policing. In 1805, New Orleans, newly arrived in the union, organized a “city guard” that ran like a military company and funded itself with a tax on slaveholders, a reflection of its role in suppressing revolt. Charleston, Savannah, Richmond, and Mobile also established paid police well before 1845, when New York City became the first Northern municipality to do so. In 1837, Charleston had the largest paid force of any American city, even though it ranked tenth in total population.45

The racial component of law enforcement stood out in Southern city statute books. Curfews, passes, badges, and bans on access to liquor, weapons, and public assembly all aimed at preventing revolt. Racial bars on high-paying occupations and access to public markets reserved the best economic opportunities for whites. Even seemingly inconsequential behavior could be outlawed if officials thought it threatened racial hierarchy; for example, New Orleans and Richmond, among other cities, banned African-American public smoking because the right to blow smoke in another’s face carried a “connotation of equality and social presence.” For some settlements, the need for paid police who could perform these multiple tasks of white supremacy motivated their initial request for municipal incorporation. Slave jails and markets created a slavery-influenced urban landscape in the South that included forts like Charleston’s Citadel, built in the wake of an 1822 insurrection panic, and a concern for street designs that facilitated surveillance of the black population. Slavery’s impact on law enforcement gave the urban South a greater militarized police presence than existed in the urban North.46

The Urban South’s Unstable Politics

In light of slavery’s need for cities, its supporters had reason to worry about the late-antebellum surge in urban free labor. As noted above, by 1860, Southern-born whites were outnumbered in the cities by a heterogeneous mix of African Americans, European immigrants, and Northern whites whose loyalty to slave-holders was questionable. African Americans, free or slave, were closely policed and could not vote, but white men could, and where their numbers were large enough they elected municipal governments that pushed against the wishes of rural planters and their urban allies. Although white workers challenged aspects of the slave regime across the urban South, they had more difficulty gaining political control in smaller cities, such as Richmond, Charleston, Savannah, and Mobile, that had higher percentages of disfranchised workers in labor forces that were 40–50 percent African American as well as higher proportions of women and nonnaturalized immigrant men.47

In the 1850s voters in the three largest slave-state cities, Baltimore, New Orleans, and St. Louis, elected governments at odds with the increasingly solid Democratic South. In Baltimore and New Orleans, the anti-immigrant but pro-slavery American or Know-Nothing Party ran things, whereas St. Louis openly defied the planters by electing Republicans who opposed slavery’s expansion. American-born white labor backed the Know-Nothings because they promised to provide public works jobs for the unemployed, combat immigrant influence, and disrupt patron-client relationships that employers had used to keep wages low and labor docile. By expanding government spending and patronage, and by encouraging working-class gangs to intimidate Democratic voters, Southern Know-Nothings experimented with machine politics that flourished later in the century. Know-Nothings made sure to avow their support for slavery, but they angered planters nonetheless when Baltimore congressman Henry Winter Davis voted for a Republican speaker of the House of Representatives and when New Orleans Know-Nothings attacked Democratic candidate P. G. T. Beauregard for hiring slaves on a federal construction project.48

Proslavery publicists such as George Fitzhugh and J. D. B. DeBow promoted urbanization as key to Southern self-sufficiency and often praised particular cities like Richmond as “a subject of just pride throughout all the Southern States” that would “lead off in every matter that concerns the honor and security of the South,”49 but these same writers worried about the increasing power of white workers in big-city politics and the trend they set for smaller cities. Commenting on the local rise of free labor, the Charleston Mercury warned that “the process of disintegration has commenced. . . . [White workers] may acquire the power to determine municipal elections; they will inexorably use it; and thus this town of Charleston, at the very heart of slavery, may become a fortress of democratic power against it.”50 These comments reflected the outlook of the Democratic Party, which by the late 1850s controlled most Southern state governments. Democrats achieved state and regional dominance because slaveholders, who dominated rural Southern politics, increasingly demanded a united front to fight Northern antislavery. City governments run by worker-supported opposition parties were a dangerous challenge to this new orthodoxy.

Proslavery politicians did not want to end urbanization but instead sought to control urban democracy. In Baltimore and New Orleans, reform movements emerged in 1857 bankrolled by urban businessmen and planters influential in state government. Officially nonpartisan so as to attract ex-Whig businessmen, Democrats allied to the party’s Southern leadership dominated these organizations. To overcome Know-Nothing police and gangs, reformers relied on state troops, federal patronage workers, and volunteer militia like Baltimore’s newly created Maryland Guard, a 300-plus unit of the sons of pro-Democratic merchants. State government also helped. In 1859, the Maryland legislature took over Baltimore’s police and courts. The next year, police arrested gang members and kept the polls clear for reformers to win election on a campaign promising law, order, and “the suppression of partisan government altogether.” New Orleans Know-Nothings survived by a combination of street muscle and an alliance to a dissident Democratic faction that thwarted a legislative takeover of city functions. Ominously for secessionists, St. Louis Republicans stopped nonpartisan reform in its tracks. In each city, foes of the machine were friends of secession, while the opposition’s rank-and-file backed the union and, during the Civil War, fulfilled proslavery fears by spearheading state-level emancipation movements.51

The Civil War ended proslavery municipal reform as well as the broader process of Old South urbanization, but echoes of the urban Old South reverberated after 1865 in machine politics, racial segregation, ethnic heterogeneity, heavily armed and quasi-militarized police, the cities’ eclipse of small towns, and the contract-labor networks that built the West. None of these aspects of modern U.S. urban history is directly and solely traceable to the Old South—New York’s paid police differed from Charleston’s, antebellum Northerners had their own struggles over machine politics, contract labor was not enslaved—but neither are they completely free of that history. The South’s brand of proslavery urbanization existed within, not outside of, the United States and just as Northern influences disrupted secessionists’ urban dreams, so too did elements of slaveholders’ blueprint for urban America find their way into the cities remade by the Civil War.

NOTES

In common usage “city,” “town,” and “village” signify a large-to-small gradient in size but have no fixed population values. For clarity, this essay classifies a city as a concentration over 10,000 people; a town as 2,500–10,000; and a village or small town as under 2,500.

1. Hinton Rowan Helper, The Impending Crisis of the South: How to Meet It (New York: Burdick Bros., 1857), 333.

2. Ibid., 56, 215; David Brown, “Attacking Slavery from Within: The Making of The Impending Crisis of the South,” Journal of Southern History 70 (August 2004): 546–549, 560, 562–563; Frank Towers, The Urban South and the Coming of the Civil War (Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press, 2004), 22.

3. Lynn Hollen Lees, “Urban Networks,” in The Cambridge Urban History of Britain, vol. 3: 1840–1950, ed. Martin Daunton (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2000), 70. Unless otherwise specified, population numbers for U.S. cities come from Joseph C. G. Kennedy, Population of the United States in 1860 (Washington, D.C.: GPO, 1864); U.S. Bureau of the Census, Population of the 100 Largest Cities and Other Urban Places in the United States: 1790 to 1990, comp. Campbell Gibson, Population Division Working Paper 27 (Washington, D.C.: U.S. Bureau of the Census 1998); Michael R. Haines, “State Populations,” in Historical Statistics of the United States: Earliest Times to the Present: Millennial Edition, vol. 1, part A: Population, ed. Susan B. Carter et al. (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2006), 180–374.

4. David Goldfield, Region, Race, and Cities: Interpreting the Urban South (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1997), 235; David R. Goldfield, Cotton Fields and Skyscrapers: Southern City and Region (1982; repr., Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1989), 64; David L. Carlton, “Antebellum Southern Urbanization,” in The South, the Nation, and the World: Perspectives on Southern Economic Development, ed. David L. Carlton and Peter A. Coclanis (Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press, 2003), 42 (2nd quotation). Also see Peter Kolchin, A Sphinx on the American Land: The Nineteenth-Century South in Comparative Perspective (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 2003), 26–27; James M. McPherson, Ordeal by Fire: The Civil War and Reconstruction (Boston: McGraw Hill, 2001), 28, 35; Robert William Fogel, Without Consent or Contract: The Rise and Fall of American Slavery (New York: W. W. Norton, 1989), 307.

5. Jan De Vries, “Problems in the Measurement, Description, and Analysis of Historical Urbanization,” in Urbanization in History: A Process of Dynamic Interactions, ed. Ad van der Woude, Akira Hayami, and Jan De Vries (New York: Oxford University Press, 1995), 44.

6. Ibid., 47; Leonard P. Curry, “Urbanization and Urbanism in the Old South: A Comparative View,” Journal of Southern History 40 (February 1974): 50.

7. Daniel R. Hundley, Social Relations in Our Southern States (New York: Henry B. Price, 1860), 26.

8. Lees, “Urban Networks,” 67–68.

9. In 1860, these cities were Baltimore, New Orleans, St. Louis, Louisville, Washington, Charleston, Richmond, Mobile, Memphis, and Savannah.

10. John M. Merriman, French Cities in the Nineteenth Century (New York: Holmes and Meier, 1981), 14; Richard M. Morse, “Cuba,” in The Urban Development of Latin America, 1750–1920, ed. Richard M. Morse, with Michael L. Coniff and John Wibel (Stanford, Calif.: Center for Latin American Studies, Stanford University, 1971), 78; Sergio Diaz-Briquets, “Cuba,” in Latin American Urbanization: Historical Profiles of Major Cities ed. Gerald M. Greenfield (Westport, Conn.: Greenwood Press, 1994), 177. For Swedish cities see http://www2.historia.su.se/urbanhistory/cybcity/nedladd/befolkn_mac/befolkning_1860_mac.txt (accessed October 2010).

11. Gavin Wright, Slavery and American Economic Development (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 2006), 66–68.

12. Isaac Candler, A Summary View of America: Comprising a Description of the Face of the Country, and of Several of the Principal Cities (London: T. Cadell, 1824), 251.

13. Alexis de Tocqueville, Democracy in America, trans. Arthur Goldhammer (New York: Library of America, 2004), 399.

14. Data interpolated from Michael J. Fishman, “Population of Counties, Towns, and Cities in the United States, 1850 and 1860” (computer file), (Chicago: University of Chicago, Center for Population Economics [producer], 1990; Ann Arbor, Mich.: Inter-university Consortium for Political and Social Research [distributor], 1990). Fishman used Kennedy, United States in 1860, which presents disproportionately high urban populations for some states. Carter et al., Historical Statistics of the United States, has been used to adjust errors.

15. Goldfield, Cotton Fields and Skyscrapers, 4; John Majewski, Modernizing a Slave Economy: The Economic Vision of the Confederate Nation (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2009), 25, 41. For town growth after 1865, see Gavin Wright, Old South, New South: Revolutions in the Southern Economy Since the Civil War (New York: Basic Books, 1986), 39–42, and Edward L. Ayers, The Promise of the South: Life after Reconstruction (New York: Oxford University Press, 1992), 20.

16. Darrett B. Rutman with Anita H. Rutman, Small Worlds, Large Questions: Explorations in Early American Social History, 1600–1850 (Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press, 1994), 251–252.

17. Carlton, “Antebellum Southern Urbanization,” 38–39 (first quotation); Alan Pred, Urban Growth and City Systems in the United States, 1840–1860 (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1980), 115–116 (second quotation); John Majewski, A House Dividing: Economic Development in Pennsylvania and Virginia Before the Civil War (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2000), 166; Goldfield, Cotton Fields and Skyscrapers, 64–65.

18. Pred, Urban Growth and City-Systems, 8; Alan Pred, “Industrialization, Initial Advantage, and American Metropolitan Growth,” Geographical Review 55 (April 1965): 168; Eric E. Lampard, “Historical Contours of Contemporary Urban Society: A Comparative View,” Journal of Contemporary History 4 (July 1969): 17.

19. Richard G. Smith, “World City Actor Networks,” Progress in Human Geography 27 (February 2003): 32 (quotation); Ben Derudder, “On Conceptual Confusion in Empirical Analyses of a Transnational Urban Network,” Urban Studies 43 (October 2006): 2027–2046.

20. E. A. Wrigley, Poverty, Progress, and Population (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2004), 267.

21. Peter A. Coclanis, “Global Perspectives on the Early Economic History of South Carolina,” South Carolina Historical Magazine 106:2–3 (2006): 130–146.

22. J. William Harris, The Making of the American South: A Short History, 1500– 1877 (Malden, Mass.: Blackwell, 2006), 99.

23. Sources in Hudson’s chapter and Kathleen Mary Hilliard, “Spending in Black and White: Race, Slavery and Consumer Values in the Antebellum South” (Ph.D. diss., University of South Carolina, 2006), 8, 17–39.

24. “Growth rate” measures simple urban population increase rather than how fast cities grew compared to total population growth, the metric used in table 7.1. On that score the South was far ahead of the North-central states for the period 1800– 1850. Richard Wade, The Urban Frontier: The Rise of Western Cities, 1790–1830 (1959; repr., Urbana, Ill.: Illini Books, 1996), 193.

25. Samuel Aby to Charles Aby, July 1, 1853, and Charles Aby to Mrs. Jonas Aby, June 20, 1855, Aby Family Papers, Mississippi Department of Archives and History, Jackson.

26. Jonathan D. Wells, The Origins of the Southern Middle Class, 1800–1861 (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2004), 96; Gregg D. Kimball, American City, Southern Place: A Cultural History of Antebellum Richmond (Athens: University of Georgia Press, 2000), 105.

27. John Rutherfoord to John Coles Rutherfoord, July 4, 1850, John Rutherfoord Papers, Rare Book, Manuscript, and Special Collections Library, Duke University, Durham, N.C.

28. William Henry Trescott to Eliza Trescot, January 28, February 15, and 16,and April 4, 1853, William Henry Trescot Papers, South Caroliniana Library, University of South Carolina, Columbia.

29. Dennis C. Rousey, “Aliens in the WASP Nest: Ethnocultural Diversity in the Antebellum Urban South,” Journal of American History 79 (June 1992): 156; Dennis C. Rousey, “Friends and Foes of Slavery: Foreigners and Northerners in the Old South,” Journal of Social History 35 (Winter 2001): 374.

30. Majewski, Modernizing a Slave Economy, 174; Richard Graham, “Slavery and Economic Development: Brazil and the United States South in the Nineteenth Century,” Comparative Studies in Society and History 23 (October 1981): 626, 631; Richard E. Boyer and Keith A. Davies, Urbanization in 19th Century Latin America: Statistics and Sources, supplement to The Statistical Abstract of Latin America (Los Angeles: Latin American Center, UCLA, 1973), 7, 9.

31. Bryan R. Roberts, The Making of Citizens: Cities of Peasants Revisited (New York: Arnold, 1995), 38.

32. Brantz Mayer, Mexico; Aztec, Spanish and Republican (Hartford: S. Drake, 1853), 34–35.

33. Camilla Townsend, Tales of Two Cities: Race and Economic Culture in Early Republican North and South America (Austin: University of Texas Press, 2000), 92.

34. Rebecca J. Scott, Degrees of Freedom: Louisiana and Cuba after Slavery (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 2005), 27; Joan Casanovas, Bread or Bullets! Urban Labor and Spanish Colonialism in Cuba, 1850–1898 (Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press, 1998), 25–27, 31.

35. Richard C. Wade, Slavery in the Cities: The South, 1820–1860 (New York: Oxford University Press, 1964), 246. Claudia Dale Goldin, Urban Slavery in the American South, 1820–1860 (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1976); Barbara Jeanne Fields, Slavery and Freedom on the Middle Ground: Maryland During the Nineteenth Century (New Haven, Conn.: Yale University Press, 1986), chap. 3.

36. Steven Deyle, Carry Me Back: The Domestic Slave Trade in American Life (New York: Oxford University Press, 2005), 149.

37. Frederick Douglass, Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, an American Slave (Boston: Anti-Slavery Office, 1845), 31; Elizabeth Keckley, Behind the Scenes, or, Thirty Years a Slave, and Four Years in the White House (New York: G. W. Carleton, 1868), 28–29.

38. Deyle, Carry Me Back, 115; Kimball, American City, Southern Place, 157.

39. Deyle, Carry Me Back, 4, 149, 155; Jonathan D. Martin, Divided Mastery: Slave Hiring in the American South (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 2004), 30.

40. Elise Dubach Isely and Bliss Isely, Sunbonnet Days (Caldwell, Idaho: Caxton Printers, 1935), 115–116.

41. Wilma A. Dunaway, “Put in Master’s Pocket: Cotton Expansion and Interstate Slave Trading in the Mountain South,” in Appalachians and Race: The Mountain South from Slavery to Segregation, ed. John C. Inscoe (Lexington: University Press of Kentucky, 2000), 117–118.

42. Martin, Divided Mastery, 22, 32; T. Stephen Whitman, The Price of Freedom: Slavery and Manumission in Baltimore and Early National Maryland (Lexington: University Press of Kentucky, 1997), 93–118.

43. Robert S. Starobin, Industrial Slavery in the Old South (New York: Oxford University Press, 1970), 11; James L. Huston, Calculating the Value of the Union: Slavery, Property Rights, and the Economic Origins of the Civil War (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2003), 100.

44. George M. Dixon, Transatlantic Rambles: or; A Record of Twelve Months’ Travel in the United States, Cuba, and the Brazils (London: George Bell, 1851), 54 (first quotation); Sharon Ann Murphy, “Securing Human Property: Slavery, Life Insurance, and Industrialization in the Upper South,” Journal of the Early Republic 25 (Winter 2005): 618 (second quotation).

45. Dennis C. Rousey, Policing the Southern City: New Orleans, 1805–1889 (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1996), 13–19, 38; Sally E. Hadden, Slave Patrols: Law and Violence in Virginia and the Carolinas (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 2001), 52–56; Robert C. Wadman and William Thomas Allison, To Protect and to Serve: A History of Police in America (Upper Saddle River, N.J.: Pearson, 2003), 35.

46. Dell Upton, Another City: Urban Life and Urban Spaces in the New American Republic (New Haven, Conn.: Yale University Press, 2008), 329 (quotation); Tom Downey, Planting a Capitalist South: Masters, Merchants, and Manufacturers in the Southern Interior, 1790–1860 (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 2006), 170; Wade, Slavery in the Cities, 266–268; Lisa C. Tolbert, Constructing Townscapes: Space and Society in Antebellum Tennessee (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1999), 259n16.

47. Towers, Urban South, 23, 56; Jacqueline Jones, Saving Savannah: The City and the Civil War (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2008), 103; William A. Link, The Roots of Secession: Slavery and Politics in Antebellum Virginia (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2003), 88.

48. Towers, Urban South, 101, 146.

49. “The Cities of the South,” DeBow’s Review 28:2 (August 1860): 187.

50. Towers, Urban South, 34–35 (quotation); Blaine A. Brownell, “The Idea of the City in the American South,” in The Pursuit Of Urban History, ed. Derek Fraser and Anthony Sutcliffe (London: Edward Arnold, 1983), 144.

51. Towers, Urban South, 155, 158, 171–172.