“Swerve me? The path to my fixed purpose is laid with iron rails, whereon my soul is grooved to run. Over unsounded gorges, through the rifled hearts of mountains, under torrents’ beds, unerringly I rush! Naught’s an obstacle, naught’s an angle to the iron way!”

—Herman Melville, Moby Dick (1851)

Let us begin with a simple railroad timetable from the 1850s. Railroad companies printed timetables on cards of varying sizes, posted them at depots, and reproduced them in handbills and in newspaper advertisements. With their long lists of arrival and departure times, mileages, and routes, the railroad timetables stood apart from many printed broadsides and pamphlets at the time because they did more than print text—they offered readers the opportunity to rehearse their movement between parts of the South and to calculate their time, distance, and route. The tables were like nothing else in the newspapers for nineteenth-century readers, eventually comparable only to financial market information and commodity prices in their complexity and detail. These abstractions of time and space represented an important break in how Americans, North and South, thought of time, geography, and themselves.

The timetable acted as a translation, a mediator, and a symbol. It signified, among other things, progress, freedom, escape, history, order, movement, mobility, control, and the future. As a means to assess one’s position on a rapidly changing network, the timetable was useful but imperfect. Railroads rarely ran on time in the North or the South, and stops along the route were dropped and missed routinely.

Like the tackle on a whaling ship, however, the railroad timetable held together a set of associations, some physical and some abstract. Towns, depots, and cities were linked together on the printed paper and brought into a practiced relationship as the trains ran between them, continually rehearsing the timetable. The timetable was an important, if silent and often forgotten, agent in the social world of nineteenth-century America, devised for a singular purpose, but used for many different applications.1

All sorts of people consulted the timetables in the South—more than we had previously realized, including slaves, women, free blacks, businessmen, planters, merchants, and politicians. The technology of the timetable, indeed of the railroad, proved widely adaptable. As it turned out, people of all classes and races shaped and adapted the railroad to their own interests. In this respect the railroad and its timetables, as well as its locomotives, rails, roadbeds, water stations, passenger depots, bridges, and tunnels, played active roles in the South in ways we have ignored. They comprised profoundly important connections between the material and social worlds and offered enormously diverse possibilities for the South in the decades before the Civil War.2

Frederick Douglass’s escape from slavery, to take a dramatic example, was brought into movement by a railroad timetable. Although he kept the exact means of his escape from slavery secret for nearly forty years, we know that Douglass consulted the Philadelphia, Wilmington, and Baltimore Railroad timetable on September 3, 1838, to plot his escape. Timing his arrival at the depot and his boarding of the northbound train with the precise time of its departure, Douglass carefully avoided any unnecessary exposure on the platform.3

White Southerners associated the railroad technologies with political power, urban development, and regional identity. The experience of these years in the South, therefore, was full of awkwardness and promise, as everywhere the modern coexisted side-by-side with the premodern, and new connections between the material and social worlds were made.

Slavery was the most obvious example. Many Northerners considered the institution a sign of backwardness, a glaring stain on the tapestry of American progress. Watching slavery from afar, some Northerners held out hope that America’s technological progress would be joined someday by moral and material progress and slavery would be ended. Frederick Douglass had great confidence in the ability of technological progress to change the moral landscape and eventually to destroy slavery. Even some white Southerners predicted that modern advances might consign slavery to the margins of history. William H. Ruffner, president of Washington College in Virginia, issued a stirring pamphlet against slavery’s expansion in 1847 and questioned whether slavery could long endure or bring material progress to the South. Ruffner argued that “the atmosphere of free States” was enough to slow slavery’s deleterious effects. He boldly proclaimed that slavery “infected” Virginia, weakening and ultimately crippling its material and cultural progress. For this he was forced to resign in disgrace.4

Despite Ruffner’s doubts, slavery proved quite adaptive to the modern age. Slave labor was used to build thousands of miles of railroads in the South. As in the North, this work went forward with crude technology and in stark contrast to the highly complex steam locomotive engines that would run on the finished tracks. To lay the tracks, workers wielded picks and shovels, axes and wheelbarrows, mules and carts. Even more surprising, Southern railroads were quick to begin purchasing slaves to help operate their lines once the hard labor of construction was finished. The modern technologies, it seemed, might extend slavery rather than rendering it obsolete, despite the fervent hopes and prayers of some Northerners and of those enslaved.

Historians have often dismissed Southern railroad development before the Civil War as antithetical to the plantation system of the South and indicative of the region’s limited priorities. Because slavery encouraged local production of cheap goods and low consumer demand, they contend, rails carried cash crops to market, but brought little back into the plantation. Furthermore, the Southern railroads were built with different gauges (width) of track, and few of them were connected, therefore to talk of a railroad “system” in the South is a fiction. Built to carry light loads, the argument goes, Southern railroads could not withstand the heavy hauling of the war, and they broke down quickly. Southern railroad management was inefficient, fractious, and ill suited to large-scale business operations, critics have charged, and because Southern roads were laid with track produced in England or the North and operated with locomotives built and fitted out in shops also outside of the South, the network, such as it was, could not be maintained in the war. One historian has summarized that, “because southern railroads relied so heavily on individual states, a ‘South’ simply did not cohere before the Civil War.”5

When we look closely at the South’s railroad culture, its experience with railroads, and the wide-ranging associations that railroads signified for Southerners, however, a different picture emerges. The South’s experimentation with and investment in railroads and other technologies, it turns out, was consistent with the rest of the nation. In retrospect, the South’s self-reliance, industry, and adaptation to technologies appear surprisingly robust. The South’s business and railroad leaders spoke in a language of expansion familiar to the North, and they faced many of the same obstacles to financing, constructing, and running their operations. Increasingly, despite the rhetoric of national unification that accompanied the railroads, regional networks coalesced in the North and South with distinctive alignments that knit together the slaveholding states. The expansion of railroads accentuated the divergent regional identities that were already taking shape in the rush of modernizing development before the Civil War.

Reshaping Slavery

On at least three levels slavery and modern railroad development in the South were fused in a relationship of profound social consequence. First, by 1860 Southern railroads became some of the largest slaveholding and slave-employing entities in the South, marking for Southerners, black and white, a consistent pattern: advanced technologies and modern development did not appear incompatible with slavery but instead inextricably linked with the institution. As early as 1841, the chairman of the board of the Louisville, Cincinnati and Charleston Railroad proposed a resolution that the directors “purchase for the service of the Rail-road, from fifty to sixty male Slaves between the ages of sixteen and thirty.” It was adopted without argument or amendment.6

By 1860 the South Carolina Rail Road Company held 90 slaves and was among the top 200 slaveholders in the city of Charleston (out of over 2,800 total slaveholders). In rural Autauwga County, Alabama, the South and North Rail Road with 121 slaves was the largest slaveholder in the county. In Baldwin County, Alabama, the Northern Rail Road held 41 slaves, and ranked among the top 25 slaveholders in the county. Although many slaveholders in the South held similarly large numbers of slaves, and some planters held many more than these companies, the railroad companies as a group in the 1850s employed over 10,000 slaves in the South and individually amassed holdings in slaves that rivaled the largest planters in the region.7

Railroad directors and officers also personally held slaves. They pursued the new technological opportunities of railroading from within their position in the slaveholding elite. In Virginia, among the directors and corporate officers of the state’s fifteen railroad companies in 1859, 87 out of 112 held slaves. Those that did not were head engineers or superintendents, men who worked directly for the companies, often at the start of their careers. The average number of slaves held by the Virginia corporate directors was twenty. Some held over ninety, and many held over fifty. The list of directors in Virginia, furthermore, included many of the top slaveholding families in the state with extensive, large-scale plantations. Virginia’s fifteen railroad presidents, despite the demands of running these new systems, included eight slaveholders, four of whom held over thirty slaves. The lower officers held slaves, too. D. S. Walton, the engineer on the Richmond and York River Railroad, held two slaves. Every class of company ownership and senior management, moreover, from engineer to president, secretary, treasurer, superintendent, and director, included slaveholders.8

Second, the extension of railroads gave white Southern slaveholders the means to dramatically enhance their property rights in slaves. The growing rail and telegraphic networks enhanced the slave trade; indeed, these technologies shaped the slave trade into a modern, information and time-sensitive market by the late 1850s. In addition, the networks gave white Southern slaveholders the ability to expand slavery into the western borderlands at a scale and speed that had important consequences for the ways they thought about their region and its growth.9

Third, and similarly, the railroads brought formerly distant regions into unexpectedly close proximity as New England free-labor, antislavery, and abolition advocates were much nearer to Kansas in 1856 than ever before. Along the borders, including some of the fastest-growing slaveholding counties in the South, slavery was no longer a distant threat to Northerners but instead a visible presence three or four depot stops away. Slavery’s strongholds were measurable in minutes on a railroad timetable from places in the free North.

The reverse was also true, of course, and the free-labor society of the North was reachable in minutes from the South at several points along the border. The modernizing effects of the railroads and telegraphs did not point in a single direction for the South. Instead, they sustained all sorts of models for how the Southern states might progress and slavery might adapt. The Baltimore and Ohio Railroad (B & O) oriented its entire operation toward free labor, employing no slaves and hiring some free blacks on its payroll. None of the directors of its subsidiary line in Virginia held slaves. Although the company never took a stand on slavery per se in the growing sectional crisis, the B & O’s great celebratory banquet in 1857 featured speeches and toasts to the Union from the abolitionist governor of Ohio, Salmon P. Chase, who praised the loyalty of the western states and by implication a free-labor society. Indeed, one B & O director toasted that the railroads would effectively “republicanize a people” by leveling class distinctions and providing equal access to mobility and modern progress. With its position skirting the border, however, the B & O became the sole exception in the South in its commitment to free labor and in its orientation to the free west. For the rest of the South, railroads advanced everywhere with slavery.10

If we look at the progress of the South in the 1850s and halt our gaze short of the Civil War, we begin to see just how rapidly and thoroughly the region’s technology was becoming associated with its civilization. When The Railroad Advocate, for example, a trade journal published out of New York, wanted to assess the state of Southern railroads in 1855, the editor, Zerah Colburn, sent a special correspondent on a tour of the South. Colburn’s correspondent reported a South brimming with modern development, a region that had harnessed slaves to the most advanced technologies of the day. He found the Seaboard and Roanoke, a road Frederick Law Olmsted traveled a year later, to be “well managed” and “well constructed.” The locomotives were built by the nation’s finest manufacturer, and the shops were equipped with “the best tools.” The entire enterprise was impressive. On the North Carolina Central, a road over 200 miles long, without a grade exceeding 50 feet, and laid with the best 60 pound iron rails available, he discovered “one of the best constructed [roads] in the country.” Its locomotives were deemed the most “beautiful machines in the country.”

When Colburn’s traveler arrived in Savannah, Georgia, moreover, the railroad station there stunned him. “To say that Savannah, Georgia, is likely to have the most complete and elegant railroad station in the country (besides being one of the very largest) may be a matter of some surprise to northern and western railroad men,” he reported. The building was 800 feet long and 63 feet wide, designed in a modern style and rivaled only by a few railroad stations in the nation, the ones in Boston and Baltimore. The road was equipped with engines exhibited at the New York Crystal Palace Exhibition. The yards included six parallel tracks, with over three miles of railroad, a remarkably large and extensive facility. The shops held the best workbenches and lathes in the business, “the best we’ve seen.”11

All of these railroads were both worked and made possible by slave labor. According to Colburn’s journal, Southern railroads had achieved through slavery an extraordinary level of quality construction at half the cost of Northern and Western railroads. And the low cost of construction through the use of slaves prompted “astonishment in more northern communities.” At a cost of $15,000 per mile to construct, the Southern railroads had achieved staggering efficiency, and Colburn praised the slaveholding railroad stockholder who let his slaves work “at cost” and who “looks for his profits not to what he can make out of the road but to what the road can, when in operation, make for him.” Northern and Western roads often cost twice as much to build, averaging by most estimates at the time between $30,000 and $35,000 per mile.12 There was much to admire about these Southern efficiencies, Colburn found himself admitting: no contractors scamming the roads for high profits, no inflated costs and padding of contracts, no secretive promoters keeping the public at arm’s length while they engineered a boondoggle.

In 1855, then, the South’s railroads, at least according to a leading Northern-based industry journal, appeared the envy of the nation, built at a level of efficiency that no Northern line could manage and equipped at the very highest levels of quality. The notion that Southern roads were all laid with “strap rail,” Colburn noted, was wrong, because all of these had been replaced with “heavy T rail.” The “best engineering talent . . . in the world” was in the South building railroads. Led by its public men, the white South had sidestepped the financial scheming and shenanigans that afflicted Northern lines, according to Colburn. And slavery was a big part of the explanation for the region’s success.

If railroad companies were buying slaves by the dozens, and leasing them by the hundreds, they were also shipping them from one part of the South to another as part of a modernized slave-trading system and market. With the growth of railroads and telegraphs in the South, slave trading took on the characteristics of other markets: time-sensitive information, networks of buyers, rapid transit, and national reach. Slaveholders and slave traders increasingly used and adapted these technologies. Slave sales shifted in the 1850s from a localized courthouse trade to a wider railroad-and-telegraph-enabled trade. Up-to-the-minute information, telegraphed from markets all over the South, affected the sales and prospects of traders. Browning, Moore, & Co., one of the largest slave traders in Richmond, Virginia, negotiated deals by telegraph, maintained close contact with the railroads, and shipped slaves out to buyers on the railroad network all over the South. So did Moore & Dawson, another Richmond slave-trading firm. One of their agents in Baltimore wired, “if I buy them I am going to . . . take the negroes and carry them by first train to Richmond.” His expense sheet listed not only the prices he paid for the slaves but clothing expenses, the house commission, and the train tickets “on negroes from Baltimore to Richmond.” Buyers used the telegraphs to deliver instructions for credit and used the railroads for quick delivery: “bring the negroes on immediately” meant load them on the trains as soon as possible. “I can be down tomorrow with five (5) Negroes,” one seller from Lynchburg wired the Richmond firm.13

In this context many white Southerners began to argue that the competition with the North had entered a new phase with the arrival of railroads, telegraphs, and steamships. When the Virginia Board of Public Works and the Blue Ridge Railroad began building a tunnel through the mountains of western Virginia, the project became symbolic of the South’s resurgent development and the region’s attempt to conquer the natural barriers to regional unity. As one of the most challenging engineering feats of the day, the tunnel drew national attention because it would be the longest tunnel in the United States. As a means to unify Virginia and the South, the tunnel served a wider purpose, a small step on the path of Southern modern economy and political independence.

The project, moreover, would link together the older Virginia Tidewater region with the more recently settled western parts of the state. Virginia seemed in many respects to be a microcosm of the South. There was, it turned out, nothing inevitable about mountainous geography and free labor. Slavery pushed into the mountains and valleys of western Virginia throughout the 1850s, often along the lines established by the railroads. The Blue Ridge tunnel, then, was strategically positioned to orient western Virginia into the dominant, slavery-based network of the state and to satisfy the long-standing grievances of westerners that they had been denied adequate transportation and support.14

In 1851 the Virginia Board of Public Works engaged one of nation’s most distinguished engineers, Claudius Crozet, to design and build the line through the mountains. Born in France and a man of wide military and engineering experience, Crozet served as the chief civil engineer for the board. He planned and surveyed the state’s development of canals, turnpikes, bridges, and railroads. By 1850 he was one of the leading engineers in the world and had written widely used textbooks and treatises.15

Slavery figured prominently in every aspect of the operation. Crozet hired contractors who brought hundreds of Irish workers to the Blue Ridge Mountains and housed them in “shanties.” White Irish laborers were put to work almost exclusively on the tunnel, the most dangerous job. In the early phases of the project, though, Crozet secured permission from the board to use enslaved labor to lay the tracks and build the roadbed, and hundreds of black slaves worked along the line. After a series of strikes, however, and after the price of white labor jumped higher in 1853–1854, Crozet moved to hire black slaves for the tunnel. Slaveholders set limits on when, where, and under what conditions slaves might work, and Crozet found that he could hire slaves only for drilling in the tunnel but not for “blasting.” “Fifty negroes in the Tunnel,” he explained, “will relieve the white hands, and enable us to have a full force at the drills.” The board, at Crozet’s urging, took out insurance policies on slaves hired in the tunnel. When two slaves were killed in the operation, Crozet attempted to deflect the board’s liability onto the Virginia Central Railroad, which owned the tracks leading to the tunnel. The attorney general of Virginia, however, determined that the board was liable and should compensate the slaveholders at fair market value. Affidavits were taken from white men who had known the slaves and who estimated their value. The state paid the slaveholders.16

When Southern railroads could not buy or lease slaves, they turned to other means. One ready source of labor was in state prisons. Virginia authorized the hiring of slave prisoners to companies in 1858 in its “Act Providing for the Employment of Negro Convicts on Public Works.” The governor of Virginia, John Letcher, negotiated the contracts with railroads, and in 1860 he sent over one hundred men and sixteen women to work on the Covington & Ohio Railroad (C & O). The C & O was the state’s premier project to follow the Blue Ridge tunnel and break through the Allegheny Mountains to the Ohio River valley. Another symbolic effort to reshape the South, the C & O project had been praised by George Fitzhugh in the dedication of his widely read treatise defending slavery, Cannibals All! Or Slaves Without Masters. The slaves sent to work there found themselves pitched into the largest construction project in the state. In 1861 with the onset of war, the project was abandoned, but in 1863 Virginia’s engineers recommended restarting it and supplying the necessary labor again by using convicts.17

For slaveholders, too, the prospect of hiring out their slaves to the railroads was financially attractive, and few passed up the opportunity. Once slaves were sent to the railroad, however, it might be months before they returned. One ex-slave from Athens, Georgia, Paul Smith, recalled that his father had worked on the first railroad in the state. When the family’s slaveholder died, the administrator of the estate “hired out most all” of the slaves to work on the railroad. The slaveholder’s wife had little say in the matter, and “it was a long time ‘fore she could get ‘em back home.”18

In the 1850s railroads in the South began to increase their use of slaves not only for the back-breaking construction of the road but for the routine operation of the line once it was built. The president of the Mississippi Central Rail Road explained that slavery would probably become the dominant means of running and maintaining the railroad. He reported that slaves could be deployed across the system and “could be controlled and directed [sic] at all times be controlled and concentrated whenever wherever an emergency may demand.” He admitted that the fifty-four slaves owned by the company represented “a small portion of the number of laborers required by the company,” but he expected the company to acquire more each year until “the company becomes the owner of all the labor that may be desired [sic] required for repairs of their road.” The deletions and edits were significant. Slaves could indeed be “concentrated” not only “whenever” but “wherever” the company needed them, and the railroad’s operations seemed especially conducive to employing slave labor.19

Much of the investment that railroad companies made in purchasing slaves would not be entirely apparent until the end of the Civil War, when accounting reconciliation required some kind of statement for the annual reports. In 1865, for example, the Mississippi Central Railroad’s annual report contained one line item of note: “Account of C. S. [Confederate States] Bonds and cost of Negroes now free: $585,237.” The Nashville and Chattanooga Railroad president was more direct in his 1867 recapitulation of the losses from the war: “We find from the books that there has been invested in negroes, in Georgia, the sum of $154,348 and negroes sold amounting to $32,805.25 leaving negro investment $121, 542.71.” This amount, he rather dryly noted, “is now, manifestly, a total loss.”20

Slavery had taken on new forms with the explosion of railroad building. There was an expectation among white Southerners that the most modernizing technology might be run entirely with slave labor. The promotion of railroads seemed to fit neatly with the idea of the South as an expansive, slaveholding, republican region. Few whites were worried about the compatibility of railroads or industry with slavery. Many thought that the South’s natural position could only be enhanced with the arrival of the railroads. In this spirit one delegate to the numerous Southern commercial conventions of the 1850s declared, “Every planter who has a dozen negroes wants a railroad running in front of his house, and every gentleman who has fifty negroes must have one running by his house and another by his kitchen.”21

The Rush to Modernity

By 1860 the South had constructed not only one of the most extensive rail networks in the world—as we shall see—but also an advanced vision for its economic and social future. It was significant that 75 percent of the total railroad mileage that the South would have at the end of the 1850s had been built during that same decade. Over 8,300 miles of track were laid down in the 1850s rush. Only the states of Ohio, Illinois, Indiana and the rest of the northwest could match this new mileage or boast a similarly rapid growth rate. Two regions—the West and the South—built railroad lines so fast that of the 22,000 new miles in the 1850s they accounted with equal shares for over 17,000 of them.22

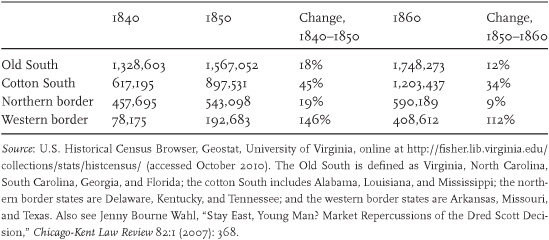

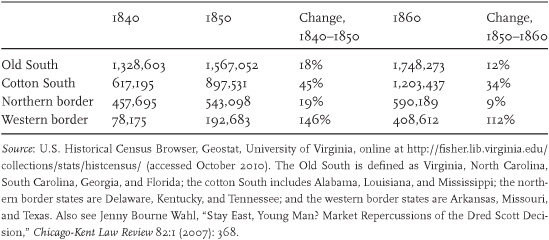

This feverish railroad building in the 1850s coincided with the rapid transfer of slaves into the southwestern region, and slave prices skyrocketed with the expansion. Slavery, it appeared, could thrive in the western territories and nearly everyone knew it. Between 1840 and 1860, as railroads extended lines westward, Southern slaveholders established themselves in the extreme western reaches where slavery was permitted. Slavery grew fastest in these places in the two decades before 1860 with the number of slaves in the western border states more than doubling from 1840 to 1860 (see table 8.1).

TABLE 8.1. Total number of slaves by subregion.

One important consequence of the rush to build railroads in the South was to enhance Southern identity as distinct from the rest of the nation. For the South, the railroads united white Southerners who were separated by vast rural spaces and overcame the region’s significant natural barriers. By 1860 the most highly populated regions of the South were linked in ways unimaginable a generation earlier. Only western Virginia, a significant exception, stood out as a major population of white Southerners out of reach of the Southern-oriented rails. In the decades before the 1840s, cities in the South seemed to have little to do with one another: information rarely circulated between them, commodities were traded more with the North, especially New York, Boston, and Philadelphia, and travelers headed out of the region rather than across and within it. But the boom in railroad construction and the emergence of telegraphic communication after 1840 linked the South’s cities and created regional networks for shared information, social interaction, and trade. By 1860 people in the smaller cities and towns across the South received their information from the region’s larger cities. Even the names of the railroad lines evoked a kind of formal bond or at least a fledgling relationship between distant Southern places: the Memphis and Charleston; the Mississippi Central; the Savannah, Albany & Gulf; the East Tennessee and Virginia.23

The different gauges of railroad in the South did not materially hinder this process of unification and common interest. Indeed, the closest study of the development of different gauge systems in the United States reveals precisely how innovative the South was in the decades before 1860. Hardly a recalcitrant and late adopter of the “standard” 4’8.5” gauge, the South experimented with different gauges just as other regions did. The 4’8.5” gauge was steadily losing its prominence in the 1840s and 1850s to other, wider gauges; by 1860, there were nine major subregions with distinct gauge standards. The period from 1855 to 1865 was the most diverse time in railroad gauge development, with only 17 percent of the entire U.S. railroad network reachable on a common gauge route without a break, either in the North or the South. The development of gauges, it turned out, depended on who the chief engineer was on a project and on what gauges were in use nearby.24

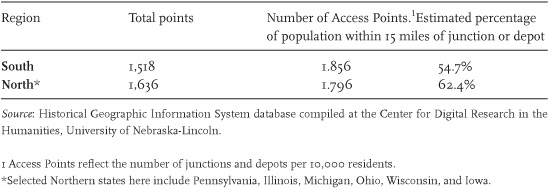

TABLE 8.2. Per capita access to railroad depots and junctions, 1861, for free population (per 10,000 persons).

By 1861 over 10,000 miles of railroad track linked cities and towns across the South. The region boasted hundreds of junctions, depots, and end points—so many that despite the South’s vast geography (compared to much of the North) the level of railroad access for its free population nearly matched Northern states and exceeded them in the number of depots and junctions per capita (see table 8.2).

In a decade the South had vaulted itself into a comparable position with much of the North in its access to railroads and all that they signified. Despite their size and difficult mountainous terrain, the states of Georgia, Tennessee, Maryland, Virginia, and South Carolina led the South in the percentage of free residents living within fifteen miles (a day’s journey on an ox-cart) of a railroad depot—all of them with access rates of over 60 percent. Although some Northern states had higher percentages of residents living within this fifteen-mile zone, the South’s per capita density of railroad structures (depots and junctions) for its free population was higher than in many Northern states. In Mississippi and South Carolina, for example, there were 3.1 and 4.8 depots per 10,000 free residents, while in Ohio there were 1.7. By this measure, whites in the South could claim by 1861 an extraordinary level of railroad penetration, investment, and accessibility.

The effects of the Southern network were more pervasive than we have imagined. Although the South had previously relied on its extensive river system for transportation and communication, railroads were what definitively broke the region’s geographic barriers. Furthermore, the network was overlaid on existing river systems and existing roads and turnpike systems. Plank roads, turnpikes, macadamized roads, and even canals combined with railroads to create a deep “system.” And because steam-powered railroads in the 1850s required a depot every eight to twelve miles for watering and fueling, the technology created a high level of access, whether the populations it served were dispersed or concentrated. In this respect New York City had no greater access to the modern technology than Resaca, Georgia. Moreover, there were universal limits to the number of tracks and length and number of cars, further democratizing access. In fact, the Southern white population, because it was dispersed and yet served by widely available railroad access points, had more direct encounters with the modernity that railroads brought.

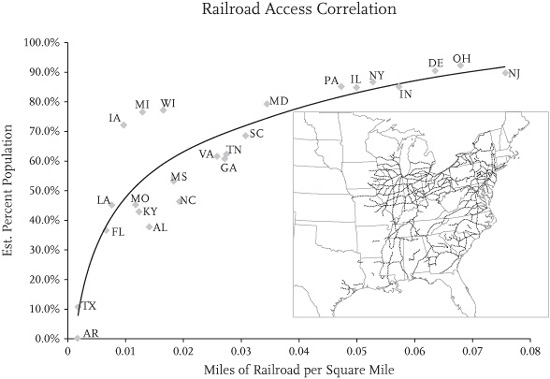

For every state there was a saturation point, a point of diminishing returns, in the development of railroad mileage and access to the network. Here, too, the pattern of Southern development was impressive and consequential. Beyond a certain point each mile of railroad that was added to a network included an increasingly small percentage of the population. For example, Ohio, one of the leading states in railroad mileage, had 295 percent more miles of railroad track than South Carolina in 1860, but only 22 percent more of its population was serviced by its railroad network. The Southern railroad network served its most densely populated areas, and, relative to the North, it brought proportionately more of its residents into contact with the railroads (see figure 8.1).25

The pattern was similar across the South: despite the costs and consequences, leading white Southerners saw these projects as modern necessities for a vibrant, powerful, modern region. A large part of these railroad projects’ appeal was the impression that they would extend the South’s slavery-based civilization, conquer nature, promise economic independence, and enable physical connections. In the Wiregrass region of Georgia, the Macon and Brunswick Rail Road got underway in the 1840s. According to a close study by historian Mark Wetherington, its growth “reflected local support for railroads” among the elite, who saw it as “one of the building blocks of civil society.” Planters and slaveholders led the effort to bring the railroad into the Wiregrass. Yeoman farmers, on the other hand, may have feared the railroads as a threat to their economic independence and stability, suspecting that the railroad would bring great changes. They knew that wherever the railroad went slave-holding, cotton farming, fence building, and timber cutting followed.26

The Wiregrass’s commercial activity was transformed in the wake of the railroad. The number of slaves per farm increased, the number of cotton bales per farm doubled. The project’s chief engineer, Albert Hall Brisbane, believed that the railroad was part of a larger commercial struggle with the North and saw his project in these competitive terms. “Sectional jealousy of the American states,” he wrote in 1849, “is beginning to exhibit itself on the score of comparative wealth.” The South could “spare no expense to eclipse” the North in the race for wealth.27

FIGURE 8.1. Railroad-access correlation logarithmic trend line graph Source: This graph includes National Historical GIS data from the University of Minnesota and railroad depot data compiled at the Center for Digital Research in the Humanities, University of Nebraska, based on original map sources.

The rush of railroad building prompted Democrats across the South to recast their Jacksonian-era fears of corporate privilege and power and to use their state’s railroad projects to secure the allegiance of upcountry voters. In Georgia these Democrats made extravagant claims that the railroad would connect the little town of Brunswick in “direct trade” with Europe. The railroad, in other words, would bypass the North, free the South, and in the great commercial and economic rivalry taking shape allow Southern planters, large and small, to dominate the trade.

Expansionists across the South, especially in the Democratic Party, believed they were in a race with the North and little seemed worth sparing in the contest, even if they had to recast their views of constitutional powers. “We are on the locomotive expansion,” the Dallas Herald declared; “The steam is up and the bell will ring soon; those that don’t want to take a ride had better get off. Sonora [Mexico] will be the next watering place.” Southern newspapers were filled with these urgent visions. “Railroad mania,” as it was sometimes called, swept the region, and Democrats were on the hustings calling for railroad access. There were skeptics, such as South Carolina’s senator James Henry Hammond, who wrote a long tract against “railroad mania.” Hammond and other Democratic Party detractors, however, objected to state aid for railroads on principle more than to railroads as a modernizing device.28

Such conflicts came part and parcel with nearly every railroad project in the South, for not all politicians were sympathetic to the grand schemes of the railroad-planter coalition, especially regarding the state aid these powerful interests repeatedly requested. Most of the opposition came from those strict constructionists and Democrats who in the tradition of Andrew Jackson feared the use of state power to concentrate wealth and capital in the form of a corporation. For the federal transcontinental project these fears were deep-seated, but they trickled down to local and state political debates as well.

Virginia’s senator James Murray Mason and South Carolina’s congressman Andrew Butler, for example, were leading strict constructionists. They saw congressional efforts to build a transcontinental railroad as an encroachment of the federal government on the power of the states and extrapolated that if a president could choose a route, he could dictate to the states where the route could run and eventually a president could extend his reach to meddle with slavery. This power, they warned, was just a first step in federal authority to control the states. Mason and Butler, followers of John C. Calhoun, fixed their opposition not on the railroad—which they wanted and for which Calhoun had advocated on behalf of the South—but on the excessive exercise of presidential power that the boom mentality might make possible.

The federal government’s refusal to consider the Southern route exacerbated North-South relations, especially because many leading white Southerners believed that nature, the landscape itself, favored the South in the race to Mexico, California, and the West. Weather played a role, as heavy snows, bitter cold, and ice blocked more northerly routes through the mountains. Ease of construction and grading were also widely discussed advantages. During the 1858 congressional debates over the location of a proposed transcontinental railroad, Alfred Iverson, Georgia’s senator, proposed two routes, one Northern and one Southern, both federally supported, and emphasized the Southern route as the cheapest to build and the most reliable. But Northern congressmen opposed the measure and ignored the arguments for the Southern route’s low cost and reliability. This opposition seemed to many white Southern leaders to fly in the face of the obvious natural advantages of the Southern route. After a decade of railroad building in the South designed to break the mountain chain and reshape the geography of the region, the Northern opposition seemed especially galling to white Southern promoters. “We cease almost to be considered as parties having rights,” Iverson lamented, echoing the concerns of John C. Calhoun eight years earlier; “Nature itself declares in our favor but her voice is disregarded.”29

The rush to build railroads in the South led its leaders to constantly recalibrate their region’s position relative to the nation’s commercial and economic network. As late as 1860 and 1861 the rush was still on. New Southern railroads were coming on line, connecting places never before linked, and adding to the dynamic of sectional examination and measurement. In this respect the 1850s marked a decisive period of change for the white South’s identity, as modern ideas, technologies, practices, and institutions were instantiated in repeated sequences across the region. The timetable, the depot platform, the locomotive, and rail bridges and tunnels offered evidence to white Southerners of the mobility and success of their society.30

For the white South the transformation of the landscape, the great engineering feats of the railroad companies, and their extensive use of enslaved labor were all tied to the widespread belief, articulated by Iverson, that “nature itself” favored the region. Indeed, nature needed to be conquered and mastered from the malarial swamps of the Tidewater to the craggy passes of the Allegheny Mountains. The effort to take this step required a massive scale of enterprise, state investment, and adaptive forms of slavery. Every Southern state participated in this movement, and, in the context of the newly acquired western territories, the stakes were increasingly significant.31

Railroad companies also moved to acquire slaves and use them to extend their lines and man their far-flung networks. As Southern railroad developers adapted slavery into the service of the new technologies, the flexibility of slavery could not have been more apparent, nor its reach more extensive, nor its consequences more alarming for many Northerners. The fastest-growing slave-holding regions of the South were also the fastest-growing railroad regions. It should not seem surprising that the Confederacy had its greatest pull, its greatest adherents, in the regions that railroads penetrated in the 1850s, nor that those places in the South with few railroads—Missouri, Arkansas, western Virginia, western Maryland, eastern Tennessee—remained on the edges of the Confederacy.

The ideas of civilization and progress, what a nation needed to claim modernity, were most strikingly evident in the way white Southerners understood the effects of railroad development. What surprised them was the North’s blatant disregard for the underlying geographic advantages that they thought nature had bestowed upon the South. The recent mastery of geography that their railroad building so clearly demonstrated seemed to count for little in the North, and yet the experience gave the white South unprecedented confidence in their modern civilization and slavery’s place in it. In this respect the Pacific Railroad Bill and its debates in the 1850s revealed to the white South that Northerners might never respect their region’s claim to modern progress.

When Virginia’s delegates met for the secession convention in 1861, three railroad directors represented their districts, two of them as outright secessionists. One of them, Thomas Branch of Petersburg, reported on his district’s resolution that “negro slaves are property.” Another railroad man, William Ballard Preston, however, took a more tempered approach. He did not favor immediate secession and instead pushed throughout the crisis for careful negotiation to achieve clear constitutional guarantees for slavery. Finally, on Tuesday, April 16, 1861, a day after President Lincoln’s call for troops to suppress secession in the lower South, William Ballard Preston, a western Virginian, a director of the Virginia and Tennessee Railroad Company, and a holder of eighteen slaves, introduced the Ordinance of Secession in the Virginia Convention. For weeks the floor of the convention had been a junction point for receiving and sending up-to-the-minute information and sparring over the right course of action. Asking for “God’s mercy,” Preston cautioned that he was not reacting to either “the influence of circumstance or telegraphic information.” Instead, his dramatic proposal came forward only after a hand-delivered, hard copy report from Washington, D.C., that confirmed Lincoln’s actions.32

Despite Preston’s reluctance to trust the news over the wires, his motion to secede and the convictions that sustained the white South were possible in large measure because of the region’s well-practiced confidence as a modern nation-state. That confidence descended from widely shared experiences with railroads and telegraphs, as symbols of modernity, as carriers of national identity, and as agents for the adaptability and extension of slavery. In this environment of rapid change, both the North and the South staked its society’s future on the railroad and what it enabled long before the Civil War. Americans in both regions knew that with secession a modern war between these nations was more than a possibility. That dim recognition was enough to give William Ballard Preston pause, but not nearly enough to stop either him or the Confederates from acting on their national vision.

NOTES

1. My concerns and approaches have been influenced here especially by “actor network theory,” as well as by the literature on the social construction of space. Bruno Latour’s views on the modern “constitution” with its separation of Nature and Society, on the importance nonhuman objects as actors, on the idea of a “sociology of associations,” and on the mediation among actors in society have been especially important in my thinking about the role of the railroad in Southern society. See Bruno Latour, Reassembling the Social: An Introduction to Actor Network Theory (New York: Oxford University Press, 2005), and We Have Never Been Modern (Cambridge, Mass: Harvard University Press, 1993). The works on space and modernity include J. Nicholas Entrikin, The Betweenness of Place: Towards a Geography of Modernity (New York: Macmillan, 1991), esp. 27–59; Allan Pred, Making Histories and Constructing Human Geographies: The Local Transformation of Practice, Power Relations, and Consciousness (Boulder, Colo.: Westview Press, 1990), esp. 126–170; Anthony Giddens, The Consequences of Modernity (Cambridge: Polity, 1990). I have also been especially influenced by Peter Onuf and Nicolas Onuf, Nations, Markets, and War: Modern History and the American Civil War (Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press, 2006), for their understanding of the South as a nation and of the Civil War as a clash of modern nation-states.

2. On the social construction of technologies, and for a recent account of the social meanings of technology and how people adapt technology to their use, see David Edgerton, The Shock of the Old: Technology in Global History since 1900 (New York: Oxford University Press, 2006). Edgerton emphasizes a history of “technology in use,” rather than invention, and the persistence of old technologies among the modern. He calls the tendency to overemphasize the impact of technology “futurism.” Here, Edgerton’s view is especially relevant because with railroads the question is how people adjusted to them, adapted, and came to terms with their use and meaning. This is predominately a cultural and social question. Other important works focused on this question include Carolyn Marvin, When Old Technologies Were New: Thinking about Electric Communication in the Nineteenth Century (New York: Oxford University Press, 1988), esp. 193–209; and David Nye, Technology Matters: Questions to Live With (Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press, 2006), esp. 46–47. Nye emphasizes that technology is not deterministic and is “unpredictable,” often with “no immediate impact.”

3. On Douglass, see Lisa Brawley, “Fugitive Nation: Slavery, Travel, and Technologies of American Identity, 1830–1860” (Ph.D. diss., University of Chicago, 1995).

4. William H. Ruffner, Address to the People of West Virginia Showing that Slavery is Injurious to the Public Welfare, and that it may be Gradually Abolished without Detriment to the Rights and Interests of Slaveholders, By a Slaveholder of West Virginia (Lexington, Va.: R. C. Noel, 1847). See also William Blair, Virginia’s Private War: Feeding Body and Soul in the Confederacy, 1861–1865 (New York: Oxford University Press, 1998), 18.

5. For analysis along these lines, see Scott Reynolds Nelson, Iron Confederacies: Southern Railways, Klan Violence, and Reconstruction (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1999), 16–45 (quotation). For a recent treatment of the South, especially Virginia, as unmodern in its development, see Susan Dunn, Dominion of Memories: Jefferson, Madison, and the Decline of Virginia (New York: Basic Books, 2007), esp. 110–112. For a traditional argument along these lines, see Robert C. Black, Railroads of the Confederacy (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1952), 282–299.

6. Proceedings of the Stockholders of the Louisville, Cincinnati and Charleston Rail-Road Company (Charleston, S.C.: A. E. Miller, 1841), Special Collections, University of Virginia Library, Charlottesville.

7. These figures come from a variety of sources. Exact numbers for railroad ownership of slaves is surprisingly difficult to pin down. The Virginia Central Rail Road leased a dozen slaves in Staunton (Augusta County), Virginia (see The Valley of the Shadow project census database at http://valley.lib.virginia.edu/ (accessed October 2010). The online resource http://www.Ancestry.com (accessed September 2010) lists slaveholders but makes no distinction between railroads that hired slaves and those that purchased them, nor do the transcribed names make it possible to search for railroads (which were abbreviated often and cryptically). One of the best (but incomplete) sources online is Tom Blake’s “Large Slaveholders of 1860” site at http://freepages.genealogy.rootsweb.ancestry.com/~ajac/ (accessed September 2010), a detailed compilation of many Southern county-level census records on slaveholders. The best records of slave ownership by railroads are the railroad company annual reports. Theodore Kornweibel, Jr., has compiled one of the most detailed accounts of slave numbers on railroads in “Railroads and Slavery,” Railroad History 34 (Fall-Winter 2003): 34–59.

8. List of company officers and directors taken from Virginia Board of Public Works, Annual Reports of Railroad Companies (1859), Charles Kennedy Collection, box 105, Special Collections, University of Nebraska, Lincoln. Slaveholding for individuals compiled and checked against Ancestry.com.

9. Gavin Wright, Slavery and American Economic Development (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 2006), 48–49. Wright’s important argument in this volume explains the significance of the large slaveholders’ capacity to dominate new areas and lands by moving enslaved labor quickly and in large numbers into them. Their high rates of return, moreover, help explain the grip that these slaveholders maintained over the institution and, in addition, its significance in the mounting sectional crisis over the western territories. See also Jenny Bourne Wahl, “Stay East, Young Man? Market Repercussions of the Dred Scott Decision,” Chicago-Kent Law Review 82:1 (2007): 361–391.

10. William Prescott Smith, The Book of the Great Railway Celebrations of 1857; Embracing a Full Account of the Opening of the Ohio & Mississippi, the Marietta & Cincinnati Railroads, and the Northwestern Virginia Branch of the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad (New York: D. Appleton & Co., 1858), 86–88.

11. The Railroad Advocate, December 16, 1854, January 20, 1855, and January 27, 1855. Colburn’s journal was based in the North and offers a different perspective on the industry’s view of Southern railroad development from the works of Frederick Law Olmsted. Olmsted’s A Journey in the Seaboard Slave States (New York: Dix & Edwards, 1856) depicted Southern railroads as badly managed and as ultimately subversive of slavery because of their implicit modernity and culture. “They [railroads] cannot be prevented from disseminating intelligence and stirring thought,” Olmsted wrote (quotation, 103).

12. The cost of railroad construction has been a subject of much debate among scholars rightly skeptical of the railroad accounting in this period. Colburn, like many others at the time, used railroad annual reports and state commission data for his basis and admitted that these estimates were rough. The 1860 Census of the United States, Preliminary Report (U.S. Bureau of the Census, Washington: GPO, 1862), contained detailed construction costs and mileage for each state and railroad and reveals the major discrepancy between Southern and Northern railroad costs per mile. In addition, there are estimates in Dionysius Lardner’s Railway Economy (London: Taylor, Walton and Maberly, 1850), 403–406. One of the best discussions of this problem is E. R. Wicker, “Railroad Investment Before the Civil War,” in Trends in the American Economy in the Nineteenth Century, Studies in Income and Wealth 24 (Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, 1960). Wicker states that as a rule New England costs were higher than the South (512). For a full analysis of railroad construction costs, see Albert Fishlow, American Railroads and the Transformation of the Ante-bellum Economy (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1965), 342–347. Fishlow estimates U.S. construction costs at $35,000 per mile. Robert W. Fogel points out that engineers estimated the cost of the Union Pacific construction, for example, at $27,500 per mile; see Robert William Fogel, The Union Pacific: A Case in Premature Enterprise (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1960), 57.

13. William F. Askew to Dickenson and Hill, February 13 and 19, 1856; William D. Hix to Moore and Dawson, July 10, 1860; and numerous telegraphic messages, Cornelius Chase Papers, box 6, folders 6 and 10, Library of Congress, Washington, D.C.

14. See William G. Shade, Democratizing the Old Dominion: Virginia and the Second Party System, 1824–1861 (Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press, 1996). See also Kenneth Noe, Southwest Virginia’s Railroad: Modernization and the Sectional Crisis (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1994), 7–8, 43, 70. For an important analysis of the South’s move toward modernization, see John Majewski, Modernizing a Slave Economy: The Economic Vision of the Confederate Nation (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2009).

15. See Robert F. Hunter and Edwin L. Dooley, Jr., Claudius Crozet: French Engineer in America, 1790–1864 (Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press, 1989), 140–160, on the Blue Ridge Tunnel construction, and Robert L. Barrett, “Claudius Crozet,” The National Railway Bulletin, 67:5 (2002). Claudius Crozet, A Treatise on Descriptive Geometry: for the Use of the Cadets of the United States Military Academy (New York: A. T. Goodrich, 1821), and An Arithmetic for Colleges and Schools (Richmond: Drinker and Morris, 1848).

16. Claudius Crozet to Board of Public Works, January 4, 1854, Blue Ridge Railroad Correspondence, 1854, no. 216, Library of Virginia, Richmond. On slavery’s adaptation to modern industries and settings, especially its legal formulations, see Jenny Bourne Wahl, The Bondsman’s Burden: An Economic Analysis of the Common Law of Southern Slavery (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1998), 54, 85–90.

17. Kornweibel, “Railroads and Slavery,” 34–59.

18. Paul Smith, Born in Slavery: Slave Narratives from the Federal Writers’ Project, 1936–1938, (Athens) Georgia Narratives, vol. 4, part 3, 336, Federal Writer’s Project, USWPA, Manuscript Division, Library of Congress, American Memory Project, Washington, D.C., http://memory.loc.gov/ammem/snhtml/snhome.html (accessed October 2010).

19. Illinois Central Railroad Company Records, IC 6 M6.51, box 27, folder 666, Newberry Library, Chicago.

20. Mississippi Central Railroad, Annual Report of the President and Directors (Holly Springs, Miss., 1855–1860), and Nashville & Chattanooga Railroad Company, Fifteenth Annual Report of the Directors and Officers of the Nashville & Chattanooga Railroad Company (Nashville: Roberts, Watterson, & Purvis, 1867), Special Collections, University of Virginia Library, Charlottesville.

21. Richard Nathaniel Griffith Means, “Empire, Progress, and the American Southwest: The Texas and Pacific Railroad, 1850–1882” (Ph.D. diss., University of Southern Mississippi, 2001), 35 (quotation). See esp. Michael John Gagnon, “Transition to an Industrial South, Athens, Georgia, 1830–1870” (Ph.D. diss., Emory University, 1999). Historians have tended to downplay the South’s industrial development in these years too much. See the most important close study of the South’s manufacturing, and its favorable comparison to the midwestern United States, in Viken Tchakerian, “Productivity, Extent of Markets, and Manufacturing in the Late Antebellum South and Midwest,” Journal of Economic History 54 (September 1994): 407–525. For an emphasis on Southern industrial development as empty rhetoric, see John McCardell, The Idea of a Southern Nation: Southern Nationalists and Southern Nationalism, 1830–1860 (New York: W. W. Norton, 1979), 126–127. The major work on the limitations of Southern industry is Fred Bateman and Thomas Weiss, A Deplorable Scarcity: The Failure of Industrialization in the Slave Economy (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1981). For a review of the economic arguments about Southern industry, see John Ashworth, Slavery, Capitalism, and Politics in the Antebellum Republic, vol. 1: Commerce and Compromise, 1820–1850 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1995), esp. 90–100 and 499–509 (appendix). Ashworth emphasizes the importance of slave resistance in shaping the context of Southern industrial development. On railway mileage, see U.S. Interstate Commerce Commission, Railway Statistics before 1890 (Washington, D.C.: Interstate Commerce Commission, 1932), 2. For an assessment emphasizing the South’s seriousness and depth of railroad investment, as well as its significance, see James A. Ward, “A New Look at Southern Railroad Development,” Journal of Southern History 39 (1973): 409–420. On Virginia and the South’s patent activity, see William H. Phillips, “Patent Growth in the Old Dominion: The Impact of Railroad Integration before 1880,” Journal of Economic History 42 (1992): 398.

22. Mileage data based on Henry V. Poor’s Manual of the Railroads of the United States, for 1868–69,(New York: H. V. and H. W. Poor, 1868) 20; Bureau of the Census, 1860 Census of the United States, Preliminary Report (Washington, D.C.: GPO, 1862), 237; and E. R. Wicker, “Railroad Investment Before the Civil War,” in Trends in the American Economy in the Nineteenth Century, Studies in Income and Wealth 24 (Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, 1960).

23. Benedict Anderson, Imagined Communities: Reflections on the Origins and Spread of Nationalism (London: Verso, 1991). Anderson emphasized the importance of newspapers in cultivating a widely shared national identity. Communication media, especially the telegraph, compounded this effect, as did rapid transportation networks that defied natural barriers. On the South’s relative position in its urban systems, see Allen Pred, Urban Growth and the Circulation of Information: The United States System of Cities, 1790–1840 (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1973), 295, 170–171, 122. Stephen Kern makes a similar point about the way technology had paradoxical effects: “It is one of the great ironies of the period that a world war became possible only after the world had become so highly united.” Stephen Kern, The Culture of Time and Space, 1880–1918 (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1983), 270.

24. Douglas J. Puffert, “The Standardization of Track Gauge on North American Railways, 1830–1890,” Journal of Economic History 60 (December 2000): 933–960. Puffert points out that railroads had every incentive to use the same gauge as the most proximate lines, not necessarily the majority gauge of the system as a whole; in other words, the gauge of the line the railroad will join mattered more than the gauge of the system as a whole. Historians continue to use the South’s gauge differences as an explanation for the South’s difficulties in the Civil War, despite the fact that the North’s gauges were just as mixed. See John Keegan, The American Civil War: A Military History (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2009), 70.

25. This research was made possible by the Center for Digital Research in the Humanities; data analysis is by C. J. Warwas, GIS specialist and cartographer for the Railroads and the Making of Modern America Project (http://railroads.unl.edu [accessed September 2010]). My concern is with passenger access and personal mobility, rather than freight. The closest study of rail and canal and wagon road networks remains Robert W. Fogel, Railroads and Economic Growth: Essays in Econometric History (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1964), esp. 79–80 for Fogel’s assessment of distance to rail and his use of a forty-mile buffer based on historical sources. We used a fifteen-mile buffer around railroad depots as a day’s journey to an access point, because our focus was personal mobility rather than freight shipping. Railroads in the 1850s were significantly more oriented to passenger business than in the later period. The technique for measuring and estimating each county population’s railroad access has been modeled on Ian Gregory, “Population Change and Transport in Rural England and Wales, 1825–1911,” paper presented at the Association of American Geographers, Boston, 2008 (in possession of the author).

26. Gagnon, “Transition to an Industrial South, 17. Mark Wetherington, Plain Folk’s Fight: The Civil War and Reconstruction in Piney Woods, Georgia (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2005).

27. A. H. Brisbane, “Detailed Report of General Brisbane, Dated June 30, 1849. Address to Richard Keily, Esq.,” in A Brief Description and Statistical Sketch of Georgia, by Richard Keily (London: J. Carroll, 1849). This can also be found in Wetherington, Plain Folk’s Fight, 41.

28. Quoted in Means, “Empire, Progress, and the American Southwest,” 52, 59.

29. Iverson quoted in Means, “Empire, Progress, and the American Southwest,” 67.

30. For an example, see Annual Report of the Philadelphia, Wilmington, and Baltimore, Railroad (Philadelphia: James A. Bryson, January 9, 1860), Charles Kennedy Collection, Special Collections, University of Nebraska-Lincoln. On the 1850s as a decisive break, see Lacy K. Ford, The Origins of Southern Radicalism: The South Carolina Upcountry (New York: Oxford University Press, 1988), 277, 359, 372; Bradley G. Bond, Political Culture in the Nineteenth-Century South: Mississippi, 1830–1900 (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1995), 110–111. Bond notes that railroads helped unite white Southerners and convey a high degree of economic independence. Indeed, he argues the boom mirrored secessionist sentiments, as the railroad’s success gave white Southerners unbounded confidence. For an important explanation of the South’s understanding of its modernity, civilization, and nation, see especially Nicholas Onuf and Peter Onuf, Nations, Markets, and War: Modern History and the American Civil War (Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press, 2006), 166, 177, 185.

31. Gavin Wright, Slavery and American Economic Development (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 2006), 48–49.

32. The three railroad directors at the Virginia Constitutional Convention were Thomas Branch of Petersburg, William Ballard Preston of Montgomery, and Lewis E. Harvie of Amelia, although many of the delegates may have been stockholders and involved in railroad promotion. See George H. Reese, ed., Proceedings of the Virginia State Convention of 1861, vol. 4 (Richmond: Virginia State Library, 1965), 24. William Freehling suggests that the timing of the completion of the Charleston and Savannah Railroad might have played a decisive role in the secession movement in South Carolina in December 1860. “A modern railroad might seem an ironic engine to further a reactionary revolution,” Freehling writes, but the celebration brought Georgians and South Carolinians together at a crucial moment in the secession crisis. William W. Freehling, The Road to Disunion, vol. 2: Secessionists Triumphant, 1854–1861 (New York: Oxford University Press, 2007), 406.