Beekeepers commonly talk about bees as just that—bees. We usually do not use the qualifying adjective, honey. We know, though, that our bees are honey bees and that they are very specific bees within a very large family. To put honey bees in context, consider that on a worldwide basis there are perhaps 20,000 different species of bees and in North America there are 2,000 to 3,000 of those species. In most of the states we can probably find about 300 species. Of all of these species, worldwide, no more than six are honey bees, and in the Western Hemisphere there is only one species, the Western honey bee. The other five species are native to Southeast Asia.

These are interesting and perhaps impressive numbers, but keep in mind that we are talking only about bees. Wasps, including hornets and yellow jackets, are not included. Bees are not wasps; wasps are not bees. The two are related and have many similarities, but they are also decidedly different. Furthermore, there are more wasps, worldwide and locally, than there are bees. To add to the confusion, in addition to bees and wasps, there are also other insects that look superficially like them—certain flies, for instance. All of this means that on a summer day, when an insect flies by and someone swats at it or ducks away from it and says, “Ugh, a bee,” it is probably not a honey bee at all, or even a bee of any kind.

To further clarify the honey bee’s place in the insect world, see the chart, which represents an abbreviated family tree for the honey bee. It shows where insects, in general, and honey bees, in particular, fit into the animal kingdom.

Unfortunately, most people do not make a distinction between the various insects of similar appearance. To them, a bee is a bee is a bee. Incidents do occur, though, and the poor honey bee gets the blame. Frequently, the actual culprit is the yellow jacket, which somewhat resembles the honey bee, hangs around at summer outings, and is known for its repeated stings. Actually, the yellow jacket is a wasp, related to the honey bee only at the suborder level. The bumblebee, a closer relative of the honey bee, adds further to the confusion because it really is a bee, (although not a honey bee), is found in many of the same places as the honey bee, and looks a little like a honey bee.

Let’s get back to our honey bee now. It is a very specific bee in the world of bees, known scientifically as Apis mellifera and known commonly as the Western or European honey bee. The honey bee’s origins are thought to be the Near East, from where it spread naturally into Africa, Europe, and Asia. It is now found in most of the rest of the world, having been carried there by settlers in the early days of colonization.

As Apis mellifera has evolved over the millennia, many subspecies or races appeared. These are found in parts of the world where this bee has spread naturally, adapting to the particular climatic and geographical specifics of the different regions.

As you browse through the various literature, you will find reference to a number of different kinds of bees: Italian, Carniolan, Caucasian, Starline, Midnite, Double Hybrid, and Buckfast are examples. Often, little information describing these different bees is included. I’ll try to clarify this a little.

First, a reminder. All of the honey bees available to us in this country are of the same species, Apis mellifera, the Western honey bee. Other species of honey bees do exist in the world, but all of the honey bees normally kept or found in North America and South America, Europe, Africa, and Australia are of this same species. The other species of honey bee are found primarily in Southeast Asia and include Apis cerana, the Eastern honey bee; Apis dorsata, the giant honey bee; Apisflorea, the little honey bee; and at least two more recently acknowledged species, Apis koschevnikovi and Apis andreniformis.

Going back to Apis mellifera, many races of this species exist throughout the world. Some of the best known are the Italian (Apis mellifera ligustica), the Carniolan (A. m. carnica), the Caucasian (A. m. caucasica), and the African (A. m. scutellata). Because all of these races are of the same species, they can crossbreed. From this crossbreeding we get the hybrids—Buckfast, Starline, Midnite, Double Hybrid, and Africanized, for instance.

Races are relatively easy to understand and they are discussed often enough so that we have a sense of their background and origin. For the most part, they are the result of evolution in geographic isolation (Italians on the Italian peninsula, for instance) where the specific climate and vegetation influenced their development over the ages. Each race has specific traits that relate to the geographic origin of that race.

Hybrids carry things a step further. Rather than letting nature continue to take its course, we have stepped in and crossbred the races, attempting to develop a “better” bee more quickly. The specifics of this betterment are a little different for each of the several hybrids available today, but they commonly include gentleness, increased honey production, and suitability to particular environments or conditions. Sometimes, this all works out and we have a bee that is better suited for a particular situation—the Buckfast bee for British-type conditions, for instance. Other times, it doesn’t work out as well—the Africanized bee is an example. (This latter, of course, was not a deliberate introduction.)

The Midnite hybrid is derived from Caucasian and Carniolan stock. The workers are dark in color and known to be extremely gentle. They are said to work at lower temperatures than other bees and to have excellent honey production capabilities. The Starline hybrid comes from Italian stock. The bees are yellow with dark stripes and markings. Their stated desirable traits include good honey production, rapid buildup in the spring, and gentleness. The Double Hybrid is a cross of the Starline and the Midnite lines and, presumably, combines the better characteristics of both these lines. The Buckfast hybrid, the result of many years of effort by Brother Adam, a monk at the Buckfast abbey in Great Britain, derives primarily from a cross of native British black bees (Apis mellifera mellifera) with Italian bees (A.m. ligustica). The Buckfast is reported to have superior honey production, gentleness, a compact brood nest, and the ability to winter on limited stores.

Maintaining a line of hybrid bees is not simple for a breeder. Many colonies are involved and constant evaluation and reevaluation of the line are required. Breeding stock is maintained through artificial insemination. The procedure is expensive in time and in money. For the individual beekeeper, maintaining a line is easier: it’s a matter of buying a new queen periodically.

Although all of the above-named races and hybrids are found in this country, the Italian bee is by far the most common race. It is an all-around good bee for our purposes and was first imported into this country in the mid-1800s. The Italian bee, or stocks that are derived from it, now comprise the majority of bees in this country, both feral and kept. This, means of course, that the same proportion of drones in this country are of Italian stock. A random queen flying out to mate is most likely to encounter and to mate with Italian drones. Therefore, any colony headed by a hybrid queen should be requeened at least every 2 to 3 years, although more often is probably better to ensure that the line is not lost through crossbreeding during supersedure or swarming.

Three kinds or castes of bee are found in a hive of honey bees: the workers, the drones, and the queen. Each is essential to the life of the colony, and each has a specific role and specific duties. Each is indispensable over the long term, although drones are not present at all times of the year, and even the queen may be absent under certain circumstances. A minimal number of workers is always present.

The total number of bees in a colony varies over the year, but for an average colony in good health at the peak of population, we can expect to find one queen, at least several hundred drones, and as many as 60,000 workers. There are exceptions to these numbers, but we will assume for the moment that they are more or less firm.

The Worker

The Queen

The Drone

All three kinds of bees are, of course, honey bees, so the obvious question is: How and why are they different? The first distinction is their sex. The queen and workers are female; the drones are male. The second distinction is the work or contribution they each make to the life of the colony. The queen and the drone have one basic contribution—reproduction. The queen’s duty is to lay eggs; the drone’s is to mate with a queen. The workers do the rest. They carry out the many and varied tasks essential to the life of the colony; that is, they work. Let’s look at all three kinds of bees more closely.

The queen is the most important bee in the colony. Her importance derives from the fact that she is unique. She is the only bee in the colony capable of laying the fertile eggs that grow and produce the life force of the colony—the workers. Those same fertile eggs also produce queens, should any be needed. A further part of the queen’s uniqueness is that she is the mother of all of the bees of the colony—workers, drones, and any queens the colony may choose to raise.

The queen’s life span is relatively long for a bee. It can be measured in years; 2 or 3 years is perhaps normal, although her life span can be longer and often is considerably shorter.

By her appearance, she is obviously related to the other bees of the colony, but there are differences. She is the largest bee, having a long, tapering abdomen, usually without color bands. Her wings, proportionately, are short, and there are no pollen baskets on her hind legs. A less obvious difference is that the queen has no wax glands for the production of beeswax. She does have a stinger, although she uses it very selectively—for stinging other queens. Reports of a queen stinging a human are very rare, almost nonexistent. Apparently, if a queen does sting a human, it is accidental or the result of extreme provocation.

The queen has two principal activities. She lays eggs, normally 1,000 to 1,500 per day, and sometimes as many as 2,000. Furthermore, by her presence she maintains colony morale and cohesion. A brief life history of the queen is as follows: An egg is laid in a suitable cell; the egg hatches to become a larva; the larva is fed royal jelly (bee milk) for the full duration of its larval life, then spins a cocoon and becomes a pupa. The pupa matures and emerges as an adult queen, which after a few days of maturation goes on a series of mating flights, mating with a dozen or so drones during a 1-or 2-day period. She then returns to the nest carrying a lifetime supply of sperm from these matings. In a few more days she takes up her duties, laying eggs. She may never again leave the colony.

The drone, although shorter than the queen, is bulkier and noticeably larger than the workers. His life span is variable but rarely longer than a few weeks. Drones do not normally live through the winter. Their period of existence is what we might refer to as the active season of the colony—the part of the year when the colony is growing, plants are blooming, bees are foraging, and queens may be flying out to mate. Drones are born throughout this active season. The life span of an individual drone is tied to the exact time in the season when he is born, and to his success or failure in fulfilling his role—mating with a queen. The end of a drone’s life is often abrupt: if he successfully mates with a queen, he dies in the act. If he is not successful and has not died of old age, he is evicted from the colony at the season’s end to die of starvation.

Other than mating with a queen, a drone does no work. He is, in fact, not equipped to work. He has no wax glands, no pollen baskets, no stinger, and no capability to collect nectar or pollen. In the usual course of events, drones are not seen outside of the hive. Their only reason to leave the hive is to seek out queens with which to mate. Because mating takes place high in the air, we seldom see drones (or queens) except in the hive or at the hive entrance as they depart and return.

The worker is the smallest of the three bees in the colony and has the shortest life span (although individual drones may live shorter ones). Her adult life span is probably about 4 to 5 weeks during the summer, the busy time of a bee’s life. The length of her life is governed by the amount of work done. She wears out her body with her labors. In the late fall and winter, with little or no work to be done, a worker may live for several months. We will consider the worker’s life in some detail as we proceed.

Each honey bee’s life can be divided into segments. For the workers, there are three—brood, house bee, and field bee. For the queen and drones there are two—brood and adult, although the adult stage can be broken into two phases, maturation and functional.

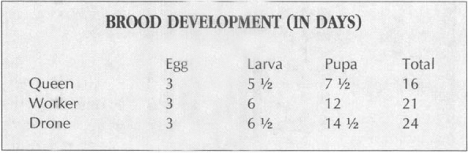

For all three castes, life starts as an egg and proceeds through the larval and pupal stages of development before emergence as an adult. The timing of this development varies for the castes. It is shown here in days.

For each caste, the beginning is the same. In fact, all castes arise from identical eggs. Any egg produced by a queen honey bee has the potential to become another queen, a worker, or a drone. The first differentiation occurs as the egg is laid. The queen has the capability to cause each egg to be fertilized or not to be fertilized as it is laid. She does this by releasing or withholding sperm as the egg passes through the oviduct. A fertile egg, after hatching, may develop as either a queen or a worker, depending on other factors that we will consider shortly. Unfertilized eggs develop into drones. This latter process is known as parthenogenesis, or virgin birth. This means that a drone has a grandfather but no father.

A worker’s life is divided into three segments: brood, house bee, and finally, field bee.

Each bee starts as an egg. As part of the act of laying, the queen first checks the cell where she plans to deposit the egg. She wants to be sure that the cell is empty and clean. She then checks to determine whether the size of the cell is that of a worker or of a drone. If the cell is of worker size, approximately ⅕ inch in diameter, she causes the egg to be fertilized as it passes from her body. She does this by releasing sperm from her spermatheca, the organ of her body that contains the sperm received from the multiple matings that took place earlier in her adult life. If the cell is of drone size, approximately ¼ inch, she does not release sperm. After 3 days, the egg hatches to become a larva.

The queen’s cell (on right) is much larger than the workers’ cells (on left), to accommodate her longer body.

For the duration of her larval life, a young worker is fed continuously. For the first 3 days, the food is exclusively royal jelly, a secretion from glands in the heads of the nurse bees. After 3 days, feeding continues, but the worker now receives ordinary brood food—glandular secretions mixed with honey and pollen.

At the end of this larval period, the developing worker spins a cocoon and enters the pupal stage. For 12 more days the pupa lies quietly and matures, after which it emerges as an adult bee. The total brood development time is 21 days. At maturation and emergence the new young bee is fully grown. She has reached her full adult size, although not all of her muscles and glandular systems are fully functional. This development, from egg through emergence, which is the brood period, takes place within a waxen cell in the heart of the colony.

Soon after emergence, the worker begins her labors. The first half of her adult life, 2 to 3 weeks, is spent in the hive as a house bee. The remainder, about 2 weeks, is spent as a field bee. As adults, these workers perform all of the many and various tasks, other than reproduction, that are necessary to the success of the colony. The actual tasks performed by each worker at any particular time depend on the needs of the colony at the moment and the particular capabilities of the worker at that time. These tasks include such activities as cleaning cells, feeding larvae, building comb, attending the queen, cleaning the hive, processing nectar into honey, guarding, and ultimately, foraging for nectar, pollen, propolis, and water. Nectar and pollen are the food supply and are collected from flowers. Water is used to dilute brood food. Propolis, a resinous material collected from the bark and buds of certain trees, is used to strengthen the comb and to seal up cracks and crevices in the hive against the weather.

The brood stage of the queen’s life is similar to that of the worker. However, three things differ: the diet, the timing, and the cell in which she develops. The worker larvae are fed royal jelly for only 3 days, but the queen larvae receive it for their full larval life, which is shorter than that of the worker. The cell for a queen is also much larger than that of either the worker or the drone to accommodate the much longer body of the queen.

On emergence, the queen is not fully developed and functional. She must grow into her job. Initially, she does much the same as workers (and drones) do: she eats, wanders about the brood nest, rests, and completes her muscular and glandular development. About 3 to 5 days after emergence, she makes the first of two or three orientation flights. She must learn her surroundings so that her subsequent mating flights will proceed smoothly. After another 3 to 5 days, she will make her actual mating flights, and another 3 to 5 days later, she will lay her first egg. Her life as a queen has begun.

Once egg laying has commenced, the queen will not leave the hive again in the ordinary course of events.

The drone’s development is not significantly different from that of the other two castes. The brood stage is the longest of the three stages, but otherwise is most like that of the workers. When drones emerge, they also stay in the brood area for a certain period while eating, resting, and maturing. It takes about 2 weeks for a drone’s reproductive organs to mature. During this time, the drones make orientation flights. As with the queen and the workers, drones must learn their way about the countryside.

Once mature, the drone spends his days alternately flying out to find a queen and eating and resting in the hive. Drone flights take place in the middle of the day and last for perhaps 30 minutes. On one of his many flights, a drone may find a queen and mate, thus ending his life, or he may die one day of old age without ever accomplishing his mission. Hundreds, perhaps thousands, of drones exist for every queen, limiting the possibilities of any particular drone mating. At the end of the active season, any remaining drones are forced from the hive to die. They are seldom allowed to winter over.

Because of his casual and often idle lifestyle, the drone has a poor reputation with many beekeepers, who feel that because drones don’t contribute to the hive, get rid of them. Efforts are often made to this end, destroying cells, brood, and sometimes, even the adult drones. This is a short-sighted attitude. Drones are necessary to the well-being of the colony, and workers will go to great lengths to raise replacements during the active season, leading to the expenditure of resources that could be better spent raising workers or foraging.

Honey bees are insects. Beekeepers often lose sight of this fact and attribute to these fascinating creatures a far higher level of intelligence and mental capability than they actually have. For the most part, bees have little control over their actions and their activities. They don’t think—they react, and their reactions are in response to specific stimuli. Bees are thought to be genetically preprogrammed from birth, their abilities at any given time being closely tied to physiological development. This theory has been supported by demonstrations showing that workers raised from artificially incubated brood, and having no contact with adult bees, behave in the same manner as workers raised in a normal hive situation.

An individual bee’s reaction to stimuli depends on its physiological development, which continues over at least the first half of a bee’s adult life. For instance, not every bee can or will sting. The inclination and ability to sting are tied to age and maturation of the bee’s venom glands, which are not fully functional until about 2 weeks into a bee’s life.

I am alluding here to factors governing a bee’s internal organs and systems. These include muscular development, which controls flight; the nervous and sensory systems, which allow for the detection of stimuli; glandular development, which permits wax and venom secretion; and genetic composition, which affects the tendency towards aggression or resistance to disease.

As might be expected, external factors also play an important role. Odor, light, heat and cold, and sound (or more properly perhaps, vibration)—the absence or presence of these factors can be significant in interpreting and controlling activities and behavior.

Time is also a factor in a bee’s life, in two respects. One is reaction time. Bees react to stimuli with amazing speed. This is typical of many insects and can be attributed, at least in part, to the very short pathways from the sensory cells to the brain. Bees also have a time sense, and respond to timed activities, such as the availability of food at a particular point and place in each day. Such responses are known to be reactions within the nervous system to a reward of sugar.

If all of this is true, patterns of behavior should be evident—and are. For instance, a bee returning to the hive with pollen pellets carried in her pollen baskets sometimes loses them before arriving at a storage cell. Even so, she will continue through the series of actions necessary to unload the pellets, not realizing that her baskets are empty. The process of collecting, transporting, and storing pollen is carried through to the bitter end, despite its futility.

Another example of patterned behavior is the bees’ reaction to smoke. The judicious application of smoke to a colony brings about a set pattern of responses involving engorgement with honey and, for reasons not completely understood, reduces the defensive reactions of the bees.

Honey bees do not have human characteristics or traits. They are not happy, they are not content, they are not mean; they cannot be accurately described by any of the terms that we use to describe human personality or temperament. However, anthropomorphism, the attribution of human traits or characteristics to nonhumans, is a handy way to interpret and to discuss honey bee (and other animal) behavior. Of course, it can lead to inaccurate and improper interpretations, which can be misleading and, sometimes, dangerous. But, as long as the true interpretation is fully understood, anthropomorphism is probably an acceptable practice.

A classic example of anthropomorphism is to judge a particular colony as mean and to accept meanness as its personality. Although some colonies have a threshold of defensiveness that makes them “mean”, it could be that a colony is suffering from some outside influence that has temporarily lowered its threshold (constant harassment by a skunk, for instance, or excessive shade). Correction of the problem could restore the colony’s equanimity.

If intelligence is the ability to apply knowledge, to reason, and to think abstractly, bees do not have intelligence. However, they are capable of learning because their behavior can be modified by experience. But, the ability to learn is not intelligence. Some examples of bee learning include the association of food and odor, the timing of food availability, and the memorization of the terrain within a fairly large area around their hives.

Do bees get to know their keeper? The answer to this question probably has more to do with the activities and behavior of the beekeeper than with those of the bees. It seems unlikely that bees get to know any one person. One reason is that the average beekeeper does not visit each hive often enough for the bees to come to know her or him. A bee lives perhaps 4 to 5 weeks during the active season. The average beekeeper probably visits each hive no more than once every 2 weeks or so, and many visits do not involve a detailed inspection of the hive contents. Most of the bees don’t have any real exposure to the beekeeper.

Bees may react differently to different people. Sometimes it’s chemistry. Bees’ lives are governed by pheromones, or odors. Humans have odors that are not noticeable to us but are noticeable to other animals, including bees. The odor of some individuals is probably offensive to bees.

Aside from odors, there are people who get along with bees better than others do, but not because the bees “know” them. It has more to do with the beekeeper’s attitude and understanding of the bees. If a beekeeper approaches a hive with confidence, opens it carefully with a minimum of thumping and banging, and does not crush or otherwise agitate the bees, they tend to remain calm. If the beekeeper is nervous or apprehensive, this can be communicated to the bees through his or her actions, and they are likely to react.

When we think about bees and life in the hive, we think primarily of the worker bee. Although the drone’s role in the total scheme of things is critical, we don’t think of him on a daily basis, as we do the workers. And, although it isn’t quite this simple, you might say that once mating is over and egg laying has become routine, we can forget about the queen unless a problem arises. For most other activities, the worker is the primary life force of the colony, whether it be brood rearing, foraging, honey production, or any of the other tasks that take place within and without the hive. A closer look at the worker’s many duties and how they are performed is worthwhile.

Any worker bee is capable at some time in her life of carrying out any task within the colony, except those that are exclusive to the queen and the drones. This statement can be qualified by recognizing that there is a genetic factor that influences capability or inclination to do certain tasks, but for our purposes this factor is not important to understanding the motivation and actions of the workers.

A worker bee emerges from her natal cell as an adult, ready to work almost immediately. She is full size at emergence, although certain of her glands and muscles must develop and mature. After an initial brief period of eating and grooming, this new, young bee begins to work. Her first duties are performed in the heart of the brood nest, and she does not stray far for several days. However, as time passes, this bee undertakes a range of duties, each dependent on at least three factors: her age and corresponding capabilities, the needs of the colony, and the time of year.

Life inside the hive is much more varied than life outside it, but over the course of her life span, a worker spends more or less equal amounts of time as a house bee and as a field bee. Let’s look a little more closely at both of these phases.

The young bee is born in the heart of the hive, in the brood nest, where it is dark and warm. She remains here for at least several days, but eventually her work takes her slowly toward the hive entrance. In fact, during her days as a house bee, she makes periodic forays to the hive entrance and beyond to take orientation flights. These forays serve a dual purpose. They allow her to learn where she lives so that she can find her way home when she goes out on her regular trips as a field bee, and they allow her to exercise and strengthen her wing muscles.

Actually, during this time, and even later as a field bee, our bee is not “busy as a bee.” In a sense, she is no busier than any other animal. About one-third of her time is spent resting or sleeping and another third may be spent patrolling, moving through the hive looking for work. If, during her patrolling, she comes across a job that needs to be done, and it is within her capabilities at that moment in her life, she will undertake it. She does not concentrate exclusively on any one task in a given time period. She is usually capable of undertaking more than one task during any developmental stage and will take on whichever of these she encounters.

Her abilities are not cumulative and she cannot perform certain tasks continually. For instance, very early in her life, each worker bee’s hypopharyngeal and mandibular glands begin to secrete brood food. These glands function for this purpose for about 1 to 2 weeks. She is then no longer able to feed brood. During the period that these glands are functioning, they do not secrete food continuously, so a given bee spends very little time actually feeding brood. Between bouts of feeding, which are often quite brief, she performs other tasks.

Not every bee performs every role for which she is qualified. There are only so many cells to be built, so many larvae to be fed, and so much guarding to be done, even in a busy season. Further-more, many tasks are strictly seasonal. For instance, little or no foraging, nectar processing, or comb building is done during the winter months in most of the country, and brood rearing is cut back drastically or stopped altogether.

Finally, at some point, the needs of the colony for new food gatherers, the ever-changing capabilities of her body, and the pressures of the new generations developing behind her push her out the door and into the life of a forager.

When the house bee graduates, she becomes a field bee and will spend the rest of her days foraging. She may collect nectar, pollen, water, or propolis during this period. However, she will tend to concentrate on one or two of these.

Foraging is not random. Except perhaps for a few scout bees, each bee, as she leaves the hive, goes after one of the specific raw materials of colony life. She collects this same material exclusively on a given trip, perhaps all day, and in some instances, throughout her entire time as a field bee. This constancy is one of the reasons that the honey bee is so valuable as a pollinator. She does not go from one flower species to another as she forages for nectar or pollen, but stays with the same species for at least that trip and usually for many trips. The pollen is then moved from like-flower to like-flower, and pollination is accomplished.

The field bee’s wings are worn down by repeated contact with flowers, foliage, and other bees in the hive. When it can no longer fly, the bee soon dies.

Many variables affect the length of a bee’s life. Her labors, both in and out of the hive, take a toll on her body. One visible manifestation of this is in the wear on her wings. This comes partly from brushing and rubbing against other bees in the busy hive and from contact with flowers and foliage as she forages. Eventually, she can no longer fly while carrying a load. Her life is effectively over and she will soon die. Actually, the bee’s worn wings more or less coincide with a particular physiological development: a bee is capable of digesting only a given amount of sugar in her life, and once she has processed that amount, her life ends. During the active season when the bees are working harder, life ends sooner. In the off season, the bees tend to be idle and eat less, so they live longer.

We have alluded several times to the needs of the colony. In a colony with little brood to raise at a particular time, young bees pass quickly through that phase of development to the next—wax secretion, perhaps. The capability to secrete brood food disappears or atrophies. This is understandable and reasonable.

However, there is another aspect to the way a bee responds to needs of the colony. Sometimes a massive disruption in colony life takes place. Perhaps insecticide has wiped out all or most of the foraging force. House bees will then mature very quickly. Some of the older house bees will graduate early and take up foraging. Younger house bees will develop faster to fill in for those departing older ones. The overall balance of activities in the colony will be quickly restored, although in numbers smaller than before the disruption.

Similar changes can take place if an insecticide is inadvertently brought back to the hive by pollen foragers. Stored in the pollen cells, insecticides may cause the death of large numbers of newly emerged young bees as they feed—potential nurse bees. Very quickly, the capability of some of the older bees to secrete brood food will regenerate, thus restoring the balance.

Of course, none of this is a result of a direct recognition of needs through any kind of judgment or thought process on the part of the bees. Everything takes place in response to the absence or the presence of pheromones given off by adults and brood, which signal the status and the needs of life in the hive.

What is the beginning of a bee’s year? We have several choices, and in a sense, the answer depends on what aspect of beekeeping we are concentrating on at the moment. Actually, as soon as we start thinking about a bee’s year, we tend to focus on hive management, which leads into the beekeeper’s year. The bee’s year and the beekeeper’s year are not necessarily the same. The fact that a nice day in early spring is when we first open the hive has little bearing on what the bees have been doing all along.

A honey bee colony is active year-round. Although there are periods of relative inactivity, there is no hibernation. The type and level of activity in the colony throughout the year are dependent on the season of the year, the climate and geography of the specific locale, and the current weather. Most of us deal with bees in a temperate climate, and this is a governing factor.

Although the colony is potentially active year-round, its level of activity varies considerably, as does the population level. This population level is a reflection of hive activity. When activities are low, as in the winter, population is low. When activity level is high or has the potential to be high, population is high. For much of North America, the population cycle of a colony is represented in the chart provided here, perhaps with local variations.

The curve reflects a healthy, normal colony with adequate food reserves and with normal forage available. Notice that the population may fall off 50 percent or more over the year. A curve representing a specific colony in a specific location would show more short-term variability, reflecting the actual conditions affecting that colony.

The curve as shown is a representation of colony life for an existing colony, one that has wintered over for at least 1 year. We will arbitrarily use mid-March as the beginning of its new year. The reason is obvious. This is the low point in a colony’s population, the time when the increased stirrings of new life offset the winter decline, and the population count is rising after a winter’s rest.

There are other dates that could be chosen as the start of a new year. Swarming time is one: it represents a new beginning for both the swarm and for the parent colony that cast that swarm. The installation date of a new package or of a nucleus is another. However, these are best understood if we first outline the rising and falling of life in an established colony.

As winter passes, the bees cluster, keeping each other warm, while normal colony life goes on inside the cluster—eating, sleeping, household chores, raising brood, and so on. The bees even fly out if the weather permits. However, bees die every day, and as a result, population falls.

Brood rearing has been underway, perhaps since mid-or early winter. The exact time it begins in the new cycle is variable, depending on such factors as the climate, the race of honey bees, and the conditions in the colony. If all goes well, the rate at which new bees emerge exceeds the rate of die-off, and the net population increases. With the stimuli of spring—lengthening days, warmer weather, blooming plants—the rate of population growth increases, leading up to maximum numbers at about the time of the summer solstice.

After the solstice, the days begin to shorten and the bees take this as a signal to begin cutting back. Up to this point, colony activities have concentrated on population expansion and nectar and pollen collection. Now, emphasis ever so subtly shifts to preparation for winter. Brood rearing continues at a good rate, but by paying careful attention you can see that it is slowly tapering off. In the early season, the bees collected great quantities of pollen and of nectar, but the bulk of these were consumed in brood rearing. Now, stores are beginning to build up and the beekeepers’ honey production is in full swing. Of course, the bees consider it their honey for the winter ahead. That’s fine—there should be plenty for all.

With late summer and the onset of autumn, population drops further and activities slow. Brood rearing cuts back more and life in the hive moves at a less frenetic pace. As the nights begin to cool (and later, the days), the bees spend more time in their cluster, and brood rearing slows to accommodate this change. No more brood can be raised, at any time of year, than can be covered and kept warm by the adult population as they cluster. No matter what the season, the brood nest must be maintained at approximately 94°F (34°C). Sometime in the late fall (the exact time is dependent on latitude and other factors pertaining to the specific colony) the queen stops laying. A 3-week period follows during which the last of her eggs hatch, the brood matures, and then all brood rearing ends. Some weeks later, at least partially in response to the lengthening days, the queen starts laying again and the new cycle is underway.

Although we hear of the queen laying 1,000, even 2,000 eggs per day, she does not start out at this rate. She works up to it slowly, but by early spring her numbers are well into the hundreds and rising. By late spring she has hit her stride, and with the renewed availability of nectar and pollen, the new year is well underway. The cycle is complete and a new one begins.

Swarming is a fact of beekeeping life. It is difficult to keep bees and not have to confront swarming at some point, or even many points in a beekeeping career. It may not be a matter of actually having swarms. With careful management, swarms can be controlled—most of the time. But management for swarm control is a part of swarming. It is important, it is often misunderstood, and sometimes, it doesn’t work. However, a beginner with a package or a nucleus hive probably will not have to cope with swarming during the first season. There are no guarantees, though, so be prepared with some understanding of the process.

The following information is not intended to be a complete explanation of swarming and swarm control. Entire books have been written about the process, and research continues. The intent is to expose you to the problem. Once you are comfortable with your bees, look more deeply into swarming and its control and prevention.

In the bees’ scheme of things, swarming is good. However, even for bees it is not always desirable for a colony to swarm. It may not have the strength required to do so successfully, the timing within the season may be poor, and the quality of the season may not allow a swarm to survive. However, the colony does not know this. It simply reacts to signals—to factors such as nectar flow, numerical strength of the colony, age of the queen, and other factors that may not relate to the ability of the swarm or the parent colony to survive. Don’t assume that the bees know what they are doing.

Swarming has a particular season, actually two particular seasons. The primary swarm season is in late spring and early summer and lasts for about 6 weeks. The season starts earlier in the south and later in the north. Depending on location, the season may begin during April or May and continue into June or July. It is somewhat variable from year to year, reflecting the actual weather of the particular year. During this primary swarm season, about 80 percent of the swarms of that year occur. You can learn the dates of the approximate swarm season for your area by talking with local beekeepers.

A secondary swarm season also exists that is less well known to many beekeepers. This period extends for about a month, starting sometime in August. During this period the other 20 percent of swarms occur. Swarms from the primary season stand a reasonable chance of surviving into the following year, but long-term survival for these late swarms is much less likely. They do not have time to become reestablished for winter. In addition, the parent colony has been badly weakened and will also have difficulty surviving.

The general reason for swarming is propagation of the species. Why a particular colony swarms at a given time is less clear, but can usually be tied to population and perceived congestion in the hive. The age of the queen is a related factor. Other factors also bear on this process and it is difficult and dangerous to oversimplify any explanation.

The preparation for swarming begins well in advance of the actual day of the event. It is triggered by some combination of conditions in and out of the hive involving population, size of the hive, age of the queen, nectar flows, weather, and other factors. The exact conditions probably vary from colony to colony. It is often difficult to look at a colony that has just swarmed or is about to swarm and discern its precise reason for swarming. Many people believe that it can be explained in simple terms and controlled by simple manipulations. But swarm control requires a thorough understanding of the process and application of specific hive management techniques.

Let’s assume that conditions in our colony are such that it is ready to swarm. Some days before the actual event, the queen begins to reduce her rate of egg laying. This is not a voluntary act on her part. It is the result of less stimulation and feeding of the queen by the workers. The queen is not in charge.

About 3 days before a swarm, the queen stops laying entirely, and some of the workers begin to harass her, shaking and mauling her. Presumably, their goal is to cause her to lose weight and bulk, getting her down to flying trim. A queen who is in full egg-laying condition cannot fly far or well and swarms often travel great distances.

Meanwhile, the workers have begun to rear several new queens, one of which will head up the parent colony after the swarm has departed. The swarm actually leaves the parent colony about the day that the first of these queen cells is capped, weather permitting. About 9 days after the swarm has departed, the new queen emerges as an adult to begin preparation for taking over the egg-laying responsibilities for the parent colony. The swarm moves on to a new home, usually some distance from the parent colony, where they establish themselves and begin life as a completely new and separate colony.

From a beekeeper’s point of view, swarming is a highly undesirable occurrence. The parent colony has lost about half of its population at the height of the honey production season. It has lost the services of a laying queen for up to 4 weeks while the new queen develops, matures, and begins to lay, which also adversely affects population. Honey production for the season can be severely reduced, if not lost altogether, and the colony may be so weakened it cannot adequately prepare for the coming winter.

Swarming is controlled by an impulse, a compelling force that takes over the colony some days before the actual emergence of the swarm. That impulse must be satisfied, which happens when the colony actually swarms or when they are made to think they have swarmed. Swarm control and prevention measures that do not recognize and take into account this swarm impulse rarely work. In fact, such measures may do more harm than good to the colony in the long run. Such inappropriate steps include confining the queen, blindly destroying queen cells, and simply adding more supers to the hive to relieve congestion without paying close attention to the overall needs of the colony.

Recognition of the importance of the swarm impulse is one of the most important lessons to be learned in beekeeping. Of course, recognizing the swarm impulse does not in itself control swarming—there are steps that must be taken. The best swarm control measures begin well in advance of the swarm season and are manipulations that prevent the swarm impulse from developing. These include regular requeening, recognizing and relieving congestion, knowing the environmental conditions that encourage swarming (for instance, a warm winter, an early spring, or strong nectar flows), and removing adult bees or brood, either permanently or temporarily.

A new colony started in the spring is not likely to swarm during that first season. A novice beekeeper should not be overly concerned about swarming, and especially should not be carried away with poorly understood or unnecessary swarm prevention techniques. However, this is one of the important areas for the new beekeeper to read about and gain additional knowledge of before the next season. Furthermore, the focus of this reading should be on activities and behavior, and on bee biology. To correctly understand swarm control and prevention, you must first understand the bee.

Nutrition is as important to honey bees as it is to any living thing, and yet, bees are more restricted in their food sources than many other creatures. During certain times of year, no outside sources of food are available to them and bees are left to their own resources. They work very hard to build up food reserves for these times. We often lose sight of the fact that bees are storing food for their own benefit, not for ours. They are anticipating the cold rainy stretches when they cannot leave the hive, the droughty conditions when no nectar or pollen is available, or the long cold winter ahead. We, too, must be aware of all of this and do our part to ensure that the colony always has adequate food.

The two principal components of an adult honey bee’s diet are honey, which they produce from nectar, and pollen. From these two sources, supplemented by water, the bees derive all of the elements of a balanced diet—carbohydrates, protein, fats, vitamins, and minerals. Carbohydrates come from the honey, in the form of sugar; protein and fats come from the pollen; and vitamins and minerals come from both.

Honey bee brood also requires food during the larval stage. Their first food is bee milk or royal jelly, a secretion from glands in the worker bees’ heads. Later in larval life, honey and pollen are added to that diet.

Not only must the bee’s diet be balanced, but food must be available continually to stimulate colony activities. The bees are aware of how much food is in reserve and how much is coming into the hive. They adjust their daily activities in accordance with this volume. Bees cannot store energy in their bodies. If there are no food reserves and no nectar coming in, the colony will soon perish. An individual bee can live only a matter of hours without sugar.

Pollen is also critical. Without pollen stores on hand, or pollen coming into the hive, no brood rearing takes place—brood rearing that is underway stops, no new brood rearing will commence, and brood that is developing may be removed by adult bees.

Let’s look a little more closely at these dietary components.

Nectar (carbohydrates). Nectar is a watery secretion available from the flowers of many plants. A principal component of nectar is sucrose, a sugar, and it is for this sugar that bees collect the nectar. The bees convert nectar to honey by reducing its moisture content and inverting the sucrose to yield two different sugars, glucose and fructose. Bees can and probably do eat a certain amount of nectar directly, but their main source of energy throughout their lives is the honey they have produced and stored. A colony cannot survive without nectar or honey continually available.

Bees cannot collect nectar from all flowers. Some flowers do not secrete nectar, whereas others do not have enough concentration of sugar to allow efficient collection. They would expend more energy collecting from these latter flowers than they would gain from the resulting honey.

Pollen (protein). Protein, in the form of pollen, is necessary for the development of the bees’ muscles, glands, and tissues. It is a component in the diet of the brood and is eaten by newly emerged adults. This consumption diminishes as the adults grow older and stops by the time they reach field bee status. However, pollen is found naturally in honey, so the bees consume some amount of it throughout their lives.

Pollen is the male reproductive part of a flower. As collected by bees, it is a microscopically fine dust that they consolidate into pellets by adding small amounts of moisture from their mouthparts. These pellets are transported back to the hive adhering to the pollen baskets on the bees’ hind legs.

Pollen is collected from a variety of different flowers, although not necessarily from the same ones as those from which they get nectar. Bees collect both nectar and pollen from some flower species, while they collect only one or the other from others. Pollens from different plants differ in nutritional content, and therefore, in their value to the bees. They should have a balanced pollen diet, although the beekeeper has little control over this. Many parts of the country have pollen shortages or deficiencies, but bees do not select for content or balance: they just collect what is there.

Pollen must be collected by the bees for it to be valuable to them. In other words, we cannot collect it from flowers and feed it to them. While collecting and storing pollen, bees add enzymes and perhaps other substances that help to preserve it and enhance its dietary value. Old pollen loses potency. After a year, it is of questionable value, but bees do not recognize this. They use whatever is available.

Vitamins. These are essential for the growth and the development of any living organism. Pollen has an exceptionally high vitamin content. Small amounts of vitamins are also found in nectar, and consequently, in honey.

Minerals. These are collected routinely as a part of nectar, pollen, and water. Bees need them, as does any living thing, but different elements and different minerals are necessary to particular functions at specific ages. Both deficiencies or the presence of certain minerals can be detrimental. For instance, salt reduces longevity.

Fats. Little is known about the need for fats. For day-to-day use, fat is available from pollen. There are fat bodies in the body cavity of honey bees that function as production and storage sites for food reserves, but these are developed primarily from sugar, not from pollen. The contents of the fat bodies vary with the season and the age of the bee.

Wax secretion is dependent on sugar consumption, and not, as might be expected, on pollen consumption.

Feeding a colony is occasionally necessary and a few words about what to feed are in order here. (When to feed is discussed in Chapters 3 and 4.) Two substances are commonly fed to bees—sugar and some form of pollen or pollen substitute.

Sugar. Two forms of sugar, other than honey, are acceptable for feeding bees: granulated sugar (sucrose) and high-fructose corn syrup. Both of these, when pure, create no problems for the bees. However, both of these (and several other forms of sugar) are found in many “impure” forms that can seriously harm, if not kill, bees. Examples are molasses, candymaking by-products, corn syrup, maple syrup or sap, high-fructose syrup such as surplus from soft drink plants, and others. The only sugar that should be used as feed for bees is table-grade granulated sugar, the same kind you use. High-fructose corn syrup should also be of food quality, with no additives.

Pollen. Protein may be fed in either of two forms—pure pollen or pollen substitute. Pure pollen can be collected at the hive entrance by the beekeeper, then cleaned, dried, and stored. Pollen traps are available for this purpose. It may then be fed back to the bees in times of need. Pollen substitute is a manufactured material containing variously such components as soy flour, brewers yeast, dry skim milk, and powdered casein. Pollen substitute is often combined with pure bee-collected pollen. In this case, the mixture is called pollen supplement. All three—pollen, pollen substitute, and pollen supplement—are fed in the same manner.

Pollen supplements can be purchased through bee supply sources in two different forms. One is dry, simply called pollen substitute. It can be fed as is, inside or outside of the hive, or it can be moistened with syrup and fed as a patty inside the hive. The second form comes in commercially prepared packages, offered under one or more trade names, and is intended to go directly in the hive.

Communication between honey bees takes place both inside and outside of the hive. This communication is extremely important to the successful life of a colony and it is reasonable to say that honey bees would not exist as we know them if they could not communicate with each other as they do. Examples of the information that bees are able to pass through various means include: locations of specific forage, whether it be nectar, pollen, or water; locations of potential new homes for a swarm; danger warnings; and specific needs within and without the hive.

Information is conveyed through the interpretation of odors (pheromones) given off by bees in particular places and under particular conditions, and through their ability to convey specific information through a so-called dance language. An understanding of the role of pheromones is important to understand the behavior and the motivations of individual bees and of colonies, and although it is not necessary for us to understand the bees’ language, it is interesting and at times helpful to be able to do so.

A pheromone is a chemical substance given off by an organism that serves as a stimulus to other organisms of the same species to cause a particular behavioral response. An organism may give off a few or many pheromones under different circumstances, affecting many aspects of its life. Pheromones are usually perceived as odors or tastes. We will simplify pheromones here and think in terms of odors.

A bee’s life is largely governed by odors. These odors are associated with most aspects of a colony’s activities. For instance, the queen gives off an odor in the hive that signals her presence to the colony at large. The brood gives off odors that signal caste and stages of development and indicate to the workers such needs as those for feeding or for cell capping. Odors deposited in an empty cell by a worker bee can indicate to the queen that the cell is empty and ready for an egg. At the hive entrance, the odor (or the absence of a correct odor) of a strange bee or other intruder indicates to the guards that there is something to be repelled. A homing odor is released at certain times of confusion to help lost bees find their way back to the hive or to help a swarm find its way to a new home. An alarm odor is associated with venom to signal the intruder’s location after stinging, so that more stings will be directed there. The list could go on and there are undoubtedly many pheromones associated with a bee’s life that are yet to be discovered.

Flowers of different plant species vary widely in the quality of their nectar, as measured by sugar content and by volume available per bloom. As a result, these flowers or crops vary widely in their economic value to the colony. It is in the bees’ best interest to forage only on those blossoms that yield the richest return. This return is usually determined by sugar concentration, but is also influenced by such factors as amount per individual bloom, concentration of the crop area, and distance from the hive. When bees forage, they do not do so blindly or randomly. Foraging is an efficient undertaking, with the colony exploiting its neighborhood to find the most rewarding sources available. Once an individual bee has found or been directed to a particular source, it remains faithful to that source for an indefinite period. This period is determined by one of two things. Either the source dries up, its time of bloom over, or the bee is made aware of an alternate source that is yielding nectar of greater economic value to the colony.

At a given time, a colony may be happily foraging on a particular source, or perhaps on more than one source if others are available of approximately equal economic value. A scout bee comes across a new source, perhaps something just coming into bloom. The scout believes the new source compares at least favorably, if not better, to the sources currently being worked. It will return to the hive and signal the existence, the location, and the relative value of this new source. But first, how can this scout bee know that the find is worth touting? To understand this, we need to understand what happens to nectar as it arrives in the hive.

The nectar must be processed to convert it into honey. This processing is carried out by the house bees. The foragers, arriving at the hive with a load of nectar, pass it off to the house bees. Each house bee involved in the processing is aware of the quality of the nectar as it comes in. House bees only reluctantly accept loads of nectar from field bees that are of lesser quality than what has been arriving, but eagerly accept loads of higher quality. Thus, field bees are kept apprised of the quality of their contribution by the speed with which they are unloaded.

A scout bee, randomly searching the countryside, may come across a new source that she recognizes to be of exceptional quality, compared to what is currently being brought in to the colony. The scout bee will take a sample of this nectar back to the hive and communicate to hivemates the existence of this new source by dancing.

Bees have several dances that they use to inform hivemates of availability, quantity, and quality of nectar; honey; pollen; water; propolis; and potential homesites. These are not truly dances but that is a convenient name for these movements.

A bee in the hive dances when it has information to convey. Other bees, potential foragers, are attracted to the movement of the dance and approach the dancing bee. They are able to interpret the dance to learn what is being touted, its quality and quantity, and its location. Keep in mind that bees do not see the dance; it is dark in the hive.

The two primary dances used to signal new foraging locations are the round dance and the wag-tail dance. These are performed by foragers as soon as they return to the hive and take place on the vertical surface of the comb, usually near the entrance of the hive, where potential foragers are resting and waiting. For the purposes of this discussion, we will assume that the new forage source in question is nectar. A forager returns to the hive carrying a sample of this new find. She may also carry on her body odors associated with the flower.

The dance involves quick short steps. The total movement is confined to a relatively small area and may continue for a few seconds or as long as a minute. Other bees become excited by the action of the dance and follow the dancer, antennae toward or touching her. The dancer may be interrupted as other bees solicit samples of the nectar she is carrying, or the dancer may stop entirely and move to a different place on the comb, where she resumes dancing. For each dance, her hivemates are able to gather specific information.

The round dance. This dance is used when sources are within 100 meters of the hive. No other distance information is conveyed. The other bees know only that the new source is somewhere within a 100-meter radius, and as a group they will randomly search in that area. The other information conveyed in the round dance is the type of forage, which is apparent by the samples offered and the odors that may be adhering to the dancer’s body.

The wag-tail dance. This dance is associated with sources more than 100 meters from the hive, but the dancer is able to convey more precise information. Within a relatively small margin of error, the exact distance and a direction is indicated.

A bee’s round dance signals to others the discovery of a new source of nectar or pollen within 100 meters of the hive.

In the wag-tail dance, the bee moves in a figure-eight pattern, always in the same direction, and the orientation of the figure-eight remains the same throughout the period of the dance. The straight line through the center indicates the direction to the source of nectar, and may be interpreted by its relation to the direction of the sun.

The wag-tail dance—performed in a figure-eight pattern—conveys the distance and direction of a new nectar source that is over 100 meters from the hive.

When the forager, the potential dancer, flies to and from the nectar source, she flies on a line that is at a specific angle to the direction of the sun. That angle is reproduced in the hive as the bee dances, using a vertical line on the comb to represent the direction of the sun. As the dancer moves through the dance pattern, she wags her abdomen and gives off low-frequency sound blips. The number of blips, the intensity of the wagging, the number of straight runs, and the duration of the dancing have variously been correlated to the distance to the forage site and its quality. The quantity of food available can also be related to the number of bees dancing.

The dance language of the bees as outlined here is unbelievable, in a sense, considering that a bee has limited brain capacity, no intelligence, and no thinking capability. It becomes even more remarkable when we realize that the bee recognizes the movement of the sun and can adjust the straight-line run of the dance to follow that movement if a large amount of time passes during the dance period. The bee can also indicate the distance that must be flown to compensate for the effects of a crosswind en route, and she will indicate the straight line shortest distance even if the route actually flown must vary to go around or over an obstruction.

The alarm dance. The alarm dance indicates that contaminated or poisonous food has arrived in the hive. The dance starts within minutes of the arrival and is performed by both house and field bees. The bees run in spirals or irregular zigzags, shaking their abdomens vigorously. As a result, all flight activity stops.

Other dances. Other dances have been recognized, among them the sickle or crescent dance, which is a transition between the round and wag-tail dances, and the cleaning dance, a solicitation by the dancer to other nearby bees to clean and groom her.

What is the importance of the dance language? It is extremely important to the bees and the success of a colony and thus to the beekeeper. But it is not something that we can control or influence in any way. We can only recognize its existence. However, consider the implications. With a dance language, the bees fully exploit the resources of their neighborhood on a timely basis. Information on the comparative quality of sources is gathered and disseminated quickly. Without the dance language, each bee would be on her own, searching randomly through the countryside until she found an acceptable source. Large amounts of time would be spent scouting, and perhaps flying excessive distances, when acceptable forage might actually be located closer to the hive.

Researchers set up a large observation hive in a deciduous forest area. They watched and interpreted the dancing and analyzed foraging behavior of this colony for an entire summer. Over this time, the bees searched a 36-square mile area. They worked relatively few patches each day, but the locations changed almost daily. The conclusion was that the bees kept moving to more desirable patches as the quality changed. They could not have done this without a sophisticated communications system.

The dance language also helps to protect the colony. Foragers subjected to hazards—pesticides, toxic nectar or pollen, predators—either never return to communicate the source, or their behavior is so modified that they do not successfully communicate.

Dancing is probably as important to the long-term success of a colony as the stinging behavior discussed on page 6. Both activities allow colonies to maintain their population levels and, in turn, allow us to enjoy our particular diet and life-style by enhancing the pollination process.