CHAPTER 2

Making Movies

Lots of people wanted to move to Los Angeles in the early 1900s. Among them were filmmakers in the East.

Movies were a new thing and just starting to become popular. The Great Train Robbery of 1903 was a landmark. It had a real story with thrilling action—a robbery, a chase scene. It was long, too—at least for the time. The Great Train Robbery lasted twelve minutes. Directors in New York and New Jersey were now looking for a better place to film even longer, more involved movies. They were tired of cramped indoor studios. They needed space. They wanted to be able to do a lot of filming outdoors. Los Angeles might be perfect. The weather was great, and there were so many different kinds of scenery: mountains, canyons, deserts, the Pacific Ocean. Also, Los Angeles was far from Menlo Park, New Jersey, headquarters of Thomas Alva Edison.

Thomas Edison was one of the world’s most famous inventors. In 1877, he had invented the phonograph, and in 1879, he created the electric lightbulb. By the late 1880s, he was concentrating on inventing a camera that took moving pictures and a projector to display them on a large screen.

Moviemakers wanted to use Edison’s new camera. Theater owners wanted to use his new movie projector so that many people could watch a movie at the same time.

Edison, however, was determined to keep control of his new inventions. Anyone who used his cameras or projectors had to pay him a fee. If they didn’t, Edison would sue.

Some early movie directors found ways to avoid paying him. One way was to head to Los Angeles, where Edison’s lawyers would have a hard time finding them.

Cecil B. DeMille

Cecil B. DeMille had been writing plays and working on short documentaries in New York City. In 1913, he moved to Hollywood. He was planning a longer movie. A Western. But filming in New York would have been impossible. He needed many outdoor locations—mountains, countryside, vast open fields. The area around Los Angeles had all that. Plus, in the winter Los Angeles had good weather, so he wouldn’t have to stop production because of rain or snow.

DeMille’s movie was called The Squaw Man. It told the story of an Englishman who travels out west and marries a Native American woman. Few directors had made movies about marriages between people of different races before. (Squaw was a term used back then for a Native American woman, but for a long time has been considered very disrespectful and racist.)

DeMille and his codirector, Oscar Apfel, had headquarters in a barn in Hollywood. They had no idea that the location, at the corner of Vine Street and Selma Avenue, would later become the center of the movie capital of the world.

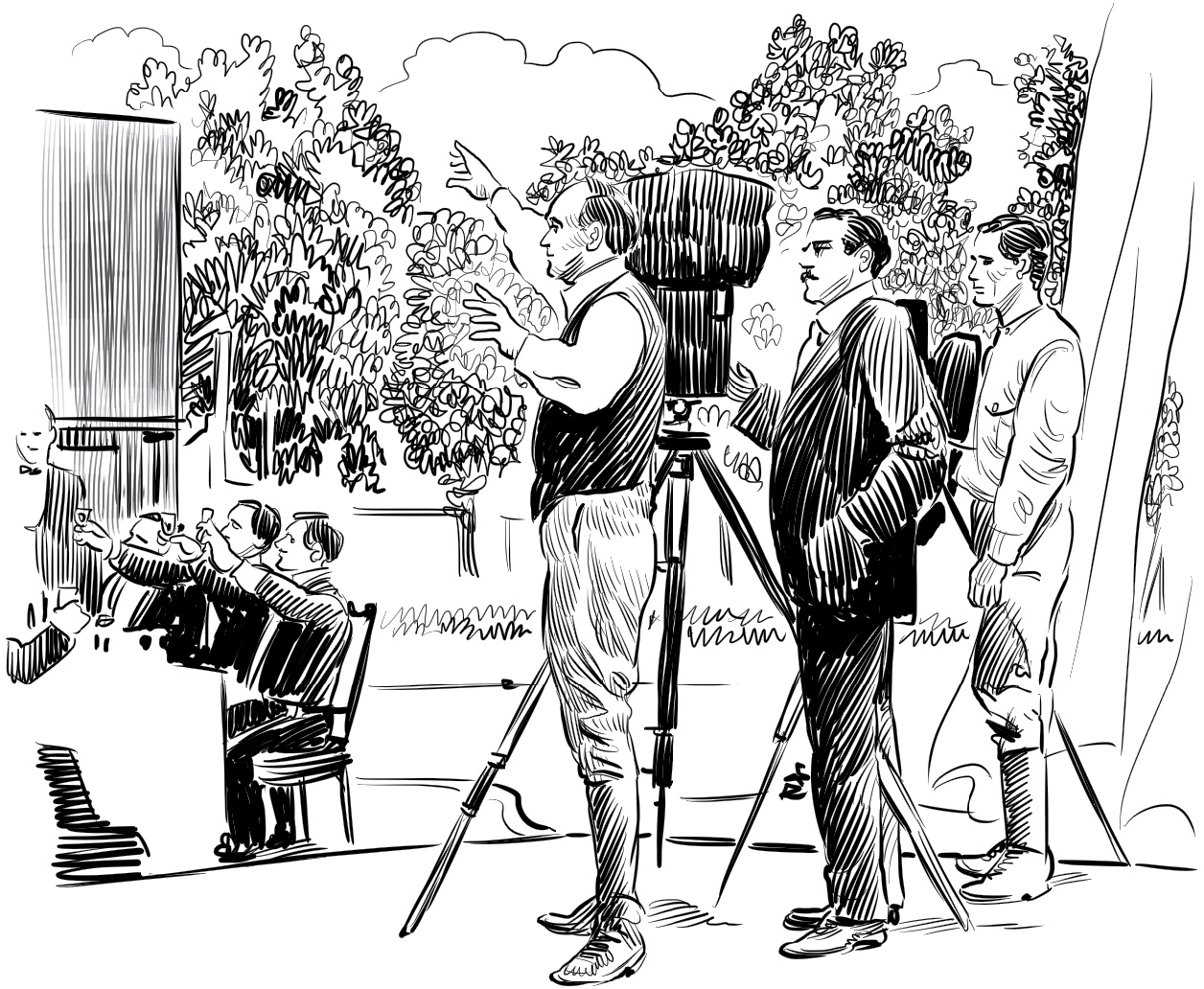

On December 29, 1913, they started filming. DeMille was very good at creating interesting characters, settings, and plots. Apfel knew how to film faraway shots, medium shots, and eye-level shots. All movies at that time were in black and white and were silent. No actors spoke lines. No one had figured out how to sync, or match up, the sound of words with actors’ moving lips. Audiences in theaters had to read important parts of the story on cards that appeared on the screen.

Movies may have been silent, but that didn’t mean there was no sound in theaters. Filmmakers often wrote musical scores. Sometimes piano players or small orchestras played the music as the movie was shown.

The Squaw Man was seventy-four minutes long. It was considered Hollywood’s first feature (full-length) film. Audiences loved it.

D. W. Griffith was another director of short films who moved to Hollywood from New York. By 1914, he was directing hour-long movies. In California, he began work on a sweeping, three-hour epic called The Birth of a Nation.

D. W. Griffith

It was about two families—one Northern, one Southern—during and after the Civil War. It followed the same characters over the course of many years. No director had done that before. One battle scene called for hundreds of extras. Nothing like that had been filmed before.

It took three months to make The Birth of a Nation. Griffith used new camera techniques: close-ups, fade-outs. The actors rehearsed their scenes before filming. That was also new.

Lillian Gish

The Birth of a Nation opened on the night of February 8, 1915. It made more money than any movie of the silent era—$18 million. That would be the same as $1.8 billion today. Its star, Lillian Gish, would become one of Hollywood’s biggest silent-screen stars.

But like The Squaw Man, The Birth of a Nation is no longer shown. That is because of the offensive way it portrays African Americans. (Not many black actors even appeared in it—most were white actors in blackface makeup.) The film portrays characters who are in the Ku Klux Klan, a white hate group, as good people. It is one of the most racist movies ever made. Civil rights groups protested outside of theaters showing it. Despite their biased stories, both The Squaw Man and The Birth of a Nation were very popular. Cecil B. DeMille went on to have a long and successful career, making epic spectacles like The Ten Commandments. He and D. W. Griffith put Hollywood on the map. Actors and directors watched these movies, saw a future career in films for themselves, and headed to California. So did businessmen with plans to build movie studios where many films could be produced at once. There was money to be made in this exciting new business. Lots of it.

Movie Palaces

Regent Theatre

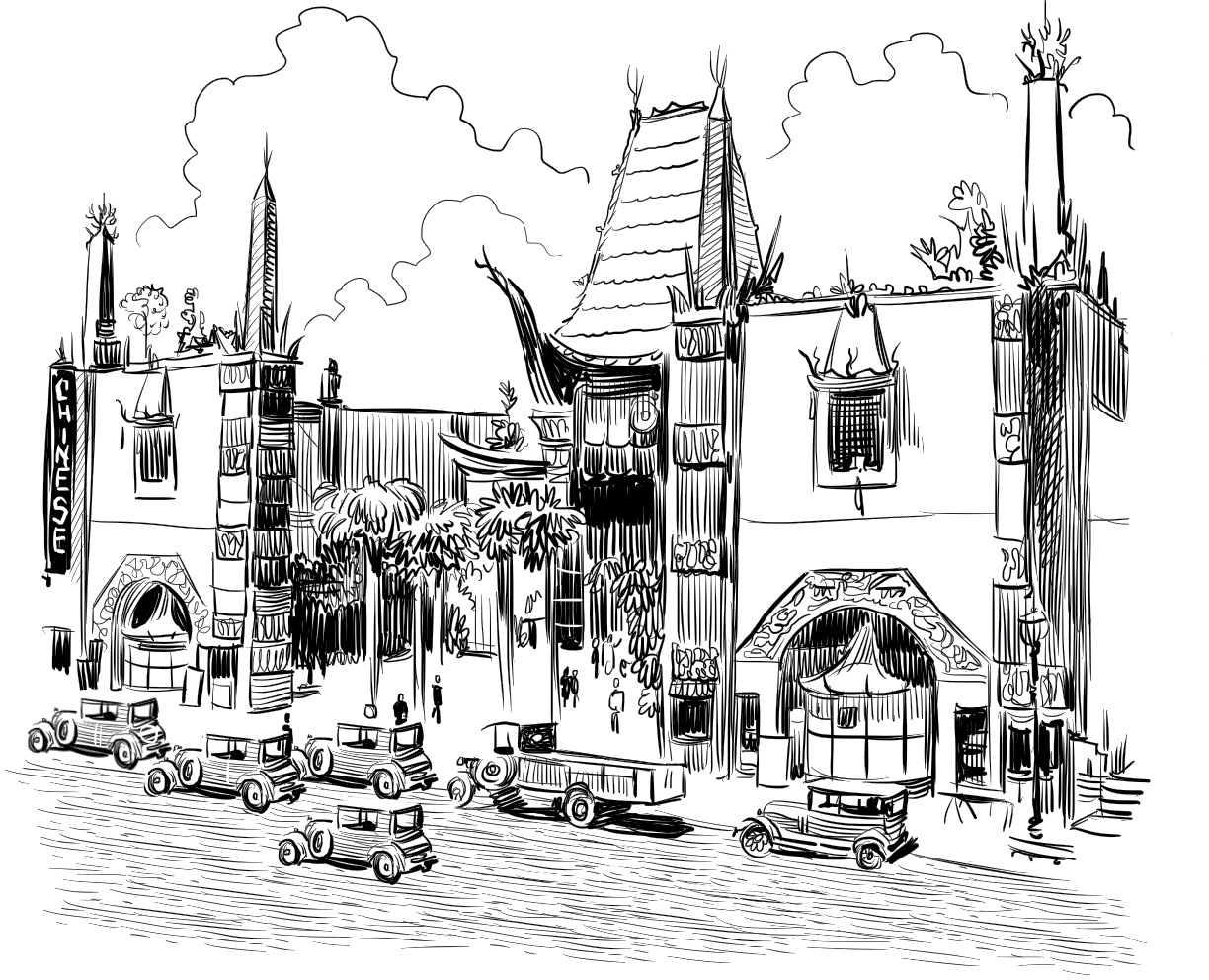

Grauman’s Chinese Theatre