Within hours after the decision was announced, District Attorney Henry Wade called a press conference at which he rather jubilantly announced: “Apparently, we’re still free to try them, so we’ll do just that.” He was referring to the fact that the Fifth Circuit Court had refused Coffee and Weddington’s request for an injunction ordering him to stop enforcing the abortion law. In effect, Wade was issuing an open invitation to the Dallas County police to crack down on illegal abortion. Furthermore, the example set by his office would be followed by district attorneys across the state of Texas.

The next day, Texas Attorney General Crawford Martin held a press conference in Austin to announce that the state would appeal the Dallas decision. In a way, Martin’s reaction was more understandable than Wade’s. The attorney general’s office at least had built its case around its moral opposition to abortion; Wade’s reaction appeared to have more to do with protecting his image as a tough law enforcer than anything else since, like law enforcement officials across the country, he had been less than diligent for years about enforcing the abortion law. About a year earlier, though, the situation had changed when a federal judge had overturned the Washington, D.C., abortion law, and the nation’s capital had become an abortion capital overnight, providing abortions not only to women who lived in the district, but also to women from all over the country. District Attorney Wade had no intention of letting that happen on his turf.

The two press conferences merely added to the confusion that followed the decision. Was abortion legal in Texas or was it not? Could doctors and hospitals perform them or not? Inquiries poured into law enforcement offices. Wade’s office did its best to discourage all abortions by telling everyone who asked that, at least as far as the district attorney was concerned, (1) the law was still what it had been before the ruling, (2) the statutes were still on the books, (3) the decision was under appeal, (4) no injunctions were issued by the federal judges against the district attorney that would preclude prosecution or following the state law, and (5) the district attorney was still prosecuting Dr. Hallford. John Tolle was assigned to act as liaison between Wade’s office and any hospitals that sought further clarification.

What this all meant was that the decision had changed nothing. If anything, abortions would now be less accessible than they had been before the ruling. Texas women were not going to be able to obtain the abortions to which they were constitutionally entitled. Coffee and Weddington were frustrated and at least a little angry, although they blamed neither Wade nor Martin. They might have liked them to work a little less diligently, but they understood that both men had to cope with public opinion, too. Besides, as lawyers they knew what was happening. They had fired the first round, and now Wade and Martin were firing the second. The third and, they hoped, final round was up to them. They needed to take their case to a higher court.

Fortunately, one result of the ruling had been to put Coffee and Weddington—especially Weddington, who was the more outgoing of the two—in touch with the pro-choice network that was rapidly taking shape across the country. As word of the Roe decision filtered through the legal world, congratulations and offers to help began to pour in, mostly from New York, where many groups were actively seeking reform, but also from lawyers around the country who were working on other abortion cases. Many of the lawyers wanted copies of the brief and the decision. Weddington and Coffee were happy to send copies of the decision to other lawyers, but the brief, only a few pages long and hastily hand-typed by Coffee, who had been racing to file Roe v. Wade before a local reporter broke the story, was not worth sending out. In return, they sought advice about the next step—where they should take their case on appeal.

The two women also were not displeased to discover that the decision and the publicity that ensued made them minor celebrities in Dallas. Deluged with invitations to speak before local groups, they soon realized they would have the forum they needed from which to address the problems that remained with the Texas abortion law, the most pressing of which, they now knew, was the fact that the judges’ ruling was not going to be respected by local law enforcement officials. Hospitals and doctors who were, in theory, free to do abortions were not about to start doing them. They also knew they would need to raise money to mount an appeal, and their newfound celebrity might help them do that.

Wherever they took an appeal, the first step was to find out whether their clients were, in fact, willing to continue with the case. Throughout all the publicity, Norma McCorvey managed to maintain her anonymity. Besides, she had just had her baby and was recuperating from childbirth and the much more painful decision to give her child up for adoption. McCorvey was quite naturally preoccupied with matters other than the decision—especially since the decision had not been of any help to her. Weddington called her to talk about the idea of appealing the case. McCorvey thought the case was settled and could not understand what was left to do, but she had become very attached to Weddington and, to paraphrase her own words, would have trusted Weddington with her life. She readily agreed, therefore, to appeal the case.

In contrast, the Does, who had come to view themselves as symbols of the reform movement, had managed to speak out publicly, although they still maintained their anonymity. Because of their activities in the pro-choice movement, they had contacts with the press and agreed to be interviewed provided their identities were not revealed. In an interview with Barbara Richardson of the Dallas Times Herald, they explained that although they had lost their case, they still felt as if the Dallas judges had ruled in their favor anyway. They wondered if “the judges might have thought that our society is not ready for that drastic a social reform.” Considerably more sophisticated about the law than McCorvey, they were eager to appeal and understood exactly what was at stake.

Given the go-ahead from their clients, Weddington and Coffee’s next problem was where to take the appeal. Everyone agreed an appeal was proper, but opinion was divided as to where the case most properly belonged. Some people thought they had to go to the next highest court, the Fifth Circuit Appellate Court, while others thought they might have a direct route of appeal to the Supreme Court. The appellate process, “inherently ponderous,” in the words of one expert, is also not unlike working one’s way through a mine field: in neither situation is there room for mistakes. Deciding where to take an appeal, or even whether the case merits one, is not always easy—and taking a wrong turn at any stage can be disastrous. The women had heard about several abortion cases rumored to be destined for the Supreme Court where lawyers had filed improper appeals and, in doing so, had irrevocably lost the right to appeal. The Wisconsin case Babbitz v. McCann would probably have been heard by the Supreme Court rather than Roe v. Wade (it had raised almost identical issues) had errors not been made in preparing the appeal.

Sometimes even experienced lawyers are unsure where to take an appeal, so Coffee and Weddington knew they needed some expert help. Although they discussed the problem with just about any lawyer who called to talk to them about the case, they again relied on the expertise of Page Keeton, dean of the University of Texas Law School; Bernard Ward, a professor who was well versed in Supreme Court procedures; and John Sutton, whom Weddington had worked for during and after law school. While they were preparing Roe for the lower court, these men had suggested that they might fall into the relatively rare category of cases that had a direct route of appeal to the Supreme Court, and now they were exploring that possibility.

Meanwhile, Coffee and Weddington made plans to file an appeal with the Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals. Better to file an appeal, they reasoned, in a court in which they were sure the case belonged than try to go directly to the Supreme Court and lose any chance of appealing in the lower federal court. Bruner, who was also planning to appeal on behalf of his client, filed for Dr. Hallford on July 23; Weddington and Coffee followed suit on behalf of their clients the next day.

Shortly after they filed their appeal in the Fifth Circuit, they learned that they did indeed have a right to appeal directly to the Supreme Court. Although people often speak of “appealing” a case to the Supreme Court, actually only a few special classes of cases come to the Supreme Court via appeal. Most come via a writ of certiorari. (Apart from their different names, though, requests for certiorari and appeals go through essentially the same process to reach the Court.) At that time, cases in which a three-judge court had been asked for and had not granted an injunction were entitled to direct appeal. Coffee and Weddington had never given any thought to laying out their case in such a way as to enhance their chances of taking it to the Supreme Court, but it now seemed that what they had initially viewed as a setback—the court’s refusal to grant injunctive relief—would prove to be a decided advantage.

To set the appellate process in motion, the appellants need only file a simple notice of appeal with the court in which the case originated. In three-judge cases, the appeal must be filed within sixty days of the final decision. This they did on August 17, 1970.

The appellants were Norma McCorvey (who filed again as Jane Roe), John and Mary Doe, and Dr. James Hallford. The party that originates an appeal is the appellant regardless of whether he or she was a defendant or plaintiff in the lower court. The next step—often a time-consuming one—is to prepare a jurisdictional statement, a special brief that must be filed within sixty days of the appeal. This is a comprehensive, sometimes lengthy document, in which the appellant presents written arguments on behalf of the case. Ostensibly these are designed to persuade the court to hear oral arguments or at minimum to affirm or dismiss the case, as one prefers.

The appellee, as the other party is called, has thirty days to respond to the jurisdictional brief. Knowing that his response will not change the Court’s consideration of the case, he may decide, as Texas did, not to file a responding brief. All this means that a case will not be “ripe for consideration,” as the Court likes to say, for a minimum of 150 days in a three-judge case (120 days in most other cases, which have different deadlines for filing).

While Coffee and Weddington were in the throes of preparing a Supreme Court appeal, they received some help from an unexpected source.

The women were never sure how Roy Lucas heard about them, probably the same way other lawyers had—through the legal grapevine. In any event, Weddington picked up the telephone one day to find him on the other end of the line. Like the many other lawyers with whom they had talked, Lucas at first seemed only to want to wish them well and find out how their case was going. When they told him about both appeals, he offered one excellent suggestion, that they file a motion in the Fifth Circuit Court to hold that appeal in abeyance pending any action by the Supreme Court. They were grateful to him for the advice.

A difference soon emerged, however, between Lucas and the other movement lawyers who had called. While attorneys such as Harriet Pilpel and Cyril Means were helpful, they seemed to recognize and respect the fact that the case belonged to Coffee and Weddington, and they offered advice only when asked. Lucas, however, gradually let it be known that he was interested in working with them in a more direct way. He presented himself so persuasively that they found him nearly impossible to refuse.

For one thing, his credentials seemed impeccable. He described the many cases he was handling across the country, including Vuitch, recently decided in a federal district court in Washington, D.C., and now, like Roe, headed to the Supreme Court. He sent them copies of the article he had written while still in law school—the first ever to outline the potential constitutional grounds for establishing women’s right to abortion.

Most important to two young, inexperienced lawyers, Lucas held out the promise of resources and badly needed funding. Although they were willing to continue working for little or nothing, they knew expenses were not minor. They certainly hoped to spend less than the $240,000 that Brown v. Board of Education reportedly cost to bring to the Supreme Court; nonetheless, one of their primary concerns was money. They would need it for the printing costs (the Supreme Court seemed to want everything in duplicates of forty) and for research. As director-general counsel of the James Madison Law Institute, which was mostly funded by civil rights activist-lawyer Morris Dees and Joseph Sunen, owner of Sunen Contraceptives, Lucas told Weddington and Coffee that he could provide both. He would help personally with fund-raising, and the institute maintained contacts with lawyers working on abortion cases across the country, often submitting amicus curiae (“friend of the court”) briefs, which were used to help support important cases. It had an extensive collection of abortion briefs upon which a model for the Supreme Court might be drafted.

The impressive board of directors for the James Madison Institute read like Who’s Who in civil rights and included such illustrious names as Yale Law School Professor Tom Emerson, who had argued Griswold in the Supreme Court; New York University Law School Professor Norman Dorsen, who had helped to establish the rights of illegitimate children and was a familiar face at the High Court; University of California Law School Professor Norval Morris; Tufts University Sociology Professor Edwin Shur; Stanford Law School Professor Anthony Amsterdam; Yale Law School Professor Charles Black; and Professor Clark Byse of Harvard Law School.

Lucas’s offer to Coffee and Weddington, when he finally got around to making it, was to handle the appeal for them. Although at the time, as Coffee would later recall in our conversations, Roy Lucas looked like welcome help, she and Weddington wavered back and forth over whether to accept his offer. On the one hand, they were keenly aware of their own inexperience—and scared to think that the burden of abortion rights for all American women rested on their shoulders. On the other hand, they were extremely proud of what they had accomplished in the Fifth Circuit Court, and they wanted to take the case to the Supreme Court by themselves. Like many other pro-choice reformers, they were beginning to develop a sense that this was somehow uniquely a woman’s issue—and to them, that meant women should take responsibility for it.

Despite their feelings, however, they suffered from the lack of any powerful female role models within the pro-choice movement. Like most other civil rights movements, the abortion movement was initially dominated by men—powerful physicians and constitutional lawyers who formed an independent old-boy clique within the abortion network. So competent and highly esteemed a lawyer as Harriet Pilpel, who had originated much of the strategy behind the constitutional right to abortion and who as counsel to Connecticut Planned Parenthood had developed the Griswold case, had not argued Griswold in the Supreme Court; that honor had been claimed by her male co-counsel, Tom Emerson.

Lucas was not above playing on the women’s insecurities by pointing out what he considered to be flaws in the way Roe had been handled at the federal court level. For one thing, the use of aliases bothered him, and he suggested they might pose a problem for the Supreme Court, too. The fact that no evidence had been presented in the lower court was another potential problem. It might give the Supreme Court a reason to send the case back to the lower court to develop the record. He hammered home the difficulties and importance of preparing a brief of Supreme Court caliber. It was a pipeline to the justices’ minds and might be all that several of them would read about abortion.

Had Coffee and Weddington had more experience, they would have known that while aliases were not common, they were not unusual, either. (The Supreme Court would not question the use of aliases, as indeed most courts did not in an era when protecting a woman’s reputation from social stigma was a serious matter.) They also would have known that throughout the 1960s, three-judge panels frequently declined to hear evidence, preferring instead to render an opinion strictly on the merits of the case. As for preparing the brief, it did seem like an enormous task, one that might require resources and funding beyond their ability. Weddington felt the lack more strongly than Coffee. From the start, when East Coast reform lawyers had strongly urged that the case should be amended to a class action suit, Coffee had resented what she viewed as unnecessary interference from outsiders. She would always believe that she and Weddington could have gotten along quite well by themselves. Her only reservation about outside help was that she planned to continue working at her job and was not sure how much time she would be able to devote to the case.

About the time Lucas was raising these issues with Coffee and Weddington, several Supreme Court rulings seemed to signal a new trend that they feared might affect Roe’s chances of being heard. The Court remanded several important cases, including two from Texas (one involving the state’s sodomy law and another involving an obscenity law), back to the lower courts so the record could be more fully developed there. The Court was reportedly trying to stem the flow of civil rights cases, and one method of doing so was to deny standing until all proper avenues of appeal at the state level had been exhausted. Both Texas cases involved criminal proceedings, as did Roe, which fueled speculation among the local press that the Roe appeal would also be sent back. Coffee and Weddington worried that they should have originated their case in a state court rather than before a federal three-judge court, and this simply added to the pressure they already felt to let Lucas handle the appeal.

In his efforts to persuade them to sign on with him, Lucas played up his experience. Although he had hardly been out of law school any longer than Weddington and Coffee, he managed to sound more worldly and experienced—how New Yorkers often managed to sound to the rest of the country. He seemed to know everyone who was actively or even peripherally involved in abortion reform on both coasts, and he had impressive ASA, ACLU, and NARAL ties. Lucas also had a way of speaking about Supreme Court justices as if he had some sort of personal pipeline to them, and he even implied that the Court preferred to hear arguments from the numerous “good” lawyers in New York and Washington, D.C., rather than two country bumpkins (although he did not, of course, say this directly).

Even if Weddington and Coffee had been inclined to do a background check on Roy Lucas (which they were not), they would have found little to alert them to potential trouble. His interest in abortion appeared to be both serious and genuine, dating back to a summer in 1969 he spent in England between his junior and senior years of law school. The liberal British abortion law had just been passed, and people in his circle were talking about little else. From home Lucas got word of another exciting boost to the reform cause, a recently published article written by former Supreme Court Justice Tom Clark, in which he had come right out and said that women had a constitutional right to abortion. The article was widely hailed by pro-choice reformers as a signal that the time was ripe to bring an appeal before the Supreme Court.

Lucas also had met and married the first of his three wives, a woman named Uta Landy, who was herself intensely interested in abortion reform. Her interest fed his, and Lucas returned to the United States and his senior year of law school imbued with the possibility of changing the abortion laws in his own country.

In the course of developing his interest in abortion reform, he made sure he met the right people. Harriet Pilpel was especially impressed when he called on her one afternoon to ask her advice on his article—so impressed that she began to mentor him through the movement. In the words of one lawyer who knew them both, she lionized Lucas, and under her auspices he was able to obtain many more plum committee assignments than anyone else of his years and experience.

It was difficult not to like Lucas. He was charming, intelligent (“damned bright,” according to Lawrence Lader), handsome, extremely personable, and smooth talking. Several years after the Roe decision, when most of his law practice consisted of helping abortion-service providers, Lucas’s willingness to fly to his clients at the drop of a hat (for a hefty fee) caused the providers to refer to him only half-jokingly as their “knight in shining fusillage.”

Admittedly, Lucas was overly aggressive, but then young lawyers were expected to be. Later his brashness and self-serving attitude would begin to wear thin with other movement activists, but it had not yet done so when he contacted Weddington and Coffee. Had they checked him out, they would have found nothing to dissuade them from working with him. After much wavering back and forth, Coffee and Weddington finally decided to let Lucas work with them, although they believed the deal they struck with him left them fully in control of their case.

When Weddington called McCorvey for the second time in several weeks to tell her that her case was being appealed to the Supreme Court, and that she and Coffee might even go to Washington, D.C., to argue it, a flabbergasted McCorvey could only stammer, “God, the Supreme Court of the United States. My God, all those people are so important. They don’t have time to listen to some little old Texas girl who got in trouble.” Weddington assured her that they did and quite possibly would.

Although Attorney General Crawford Martin had announced that he would appeal, no one in his office had much time to devote to preparing an appeal, and the opportunity to do so might have been lost had Assistant District Attorney John Tolle not begun preparing an appeal as soon as the decision was handed down. Strictly speaking, the case no longer involved Henry Wade and his staff. Since the attorney general was charged with responsibility for defending the laws of the state, the case was now officially his to contend with. The district attorney’s office typically bowed out at this stage, but Tolle had developed a special interest in the case and hoped to continue working on it. The attorney general’s people were so overburdened that, by their own admission, they often let cases slip through the cracks by failing to take appropriate legal action within the required time. Determined not to let this happen with Roe, Tolle decided to go ahead and initiate an appeal. Later he and Floyd could talk about working together. Tolle believed if they joined forces, they could build a better case in the appeals court.

Like everyone else working on Roe, Tolle was at first unclear about where to take the appeal. He soon determined that the state’s appeal properly belonged in the Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals. The basis for the appeal was that the state did not believe its abortion law was unconstitutionally vague or overbroad. The state, unlike the plaintiffs, had no right to a direct appeal to the Supreme Court; instead, it could only take the case to the next highest federal court.

On July 10 Tolle had filed the first appeal in the entire case with the Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals. When he notified Assistant Attorney General Jay Floyd of his action, Floyd wrote back, thanking him and indicating that the attorney general’s office would handle the case from here on out. A disappointed Tolle realized he would no longer be working on the abortion case.

Throughout the summer and fall of 1970, Lucas and the Madison Law Institute took over much of the work on Roe v. Wade, which largely consisted of arranging for the lower court record to be submitted to the Supreme Court and getting the jurisdictional statements printed in multiple copies and delivered to the Court.

On October 30, 1970, Lucas was notified by the Fifth Circuit clerk that the record had been submitted to the Supreme Court. In November Lucas was told that the docket fee was due at the Supreme Court. That meant the case was being docketed, and, if all went well, the justices would soon consider whether or not to take the case.

In fall 1970 one of the cases that came in on appeal to the Supreme Court was Roe v. Wade. The Court dealt with it as it did all other cases.

Petitions for certiorari and appeals are distributed to all the justices for review. Although each considers the applications separately, the justices do not discuss all 3,800 requests that come their way each year at conference. In about 70 percent of the cases, they agree that a case is frivolous or before their court improperly, and it is removed from the agenda without further discussion. The remainder are put on a list to be discussed at conference. A minority of four votes are needed to take a case.

Constitutional scholar Norman Dorsen has said that he would not be surprised if Justice Harry Blackmun had been influential in the decision to take the case. One can even reconstruct what might have happened at the conference when Roe v. Wade was first discussed. In favor of hearing an abortion case were undoubtedly Justices William Brennan, Thurgood Marshall, and William Douglas, the Court’s stalwart liberals. They were all that remained of the Warren Court’s liberal majority that had expanded civil and minority rights so diligently throughout the 1960s. On the opposite side, literally and figuratively, were probably Chief Justice Burger, in his second term, and Justice Potter Stewart, an Eisenhower appointee and strict constructionist who had generally opposed expansion of civil rights. A surprising member of the bloc that opposed liberalizing the abortion laws was Justice Byron White, a Kennedy appointee. White, who had been Robert Kennedy’s number-two man in the Justice Department, was known to be tough on both crime and civil rights violations. His opinion on women’s rights was unknown, but he could reasonably have been expected to join the liberal bloc. Instead, he opposed liberalized abortion. Justices John Marshall Harlan and Hugo Black had died within weeks of each other shortly before the Court reconvened, so only seven justices were sitting, one more than the minimum needed for the Court to conduct any business.

There remained Harry Blackmun, the most junior justice, who had joined the Court the previous June. Blackmun’s leanings on abortion were unknown. (Justices do come to the Court with a history of political activity, but their past voting records are not always the best evidence of how they will react or vote once they have joined the Supreme Court. In fact, Supreme Court justices in recent years have more often than not proven to be disappointments to the presidents who have appointed them.) The third choice of President Nixon, after his two earlier nominees Clement Haynesworth and Harrold Carswell had failed to win consent from the Senate, Blackmun had maintained a low profile since coming on the Court. He was a midwesterner, a fact that was reflected in his pragmatic approach to everything, including the law. After attending Harvard Law School, Blackmun had worked in private practice for sixteen years; when appointed to the Eighth Circuit, he developed a reputation as a hardworking, capable jurist. The experience in his life that carried the most weight on this case, however, was the period between 1950–59 when he had served as resident counsel to the Mayo Clinic, nine years that were, by his own account, among the most exhilarating in his life. Blackmun was at Mayo during the exciting pioneer years of heart surgery, and what he witnessed there left him with an enduring, almost reverential respect for physicians.

Blackmun was the only justice with any serious medical experience. If he said the case was important and deserving of the Court’s attention, that undoubtedly would have carried considerable weight with the other justices.

Only 5 percent of all cases were scheduled for oral argument. Despite these poor odds, pro-choice reformers badly wanted a case to be heard by the Supreme Court. Reformers worried that if the decision were left up to the individual states, the abortion laws would end up in a constant state of revision, as state legislatures alternately loosened and tightened the laws in accordance with the vagaries of their political constituencies. And of course, the ultimate issue revolved around the fact that if women had a constitutional right to abortion, as most reformers and the majority of Americans now believed they did, then it would not do to deny women access to abortion in one state while permitting it in another.

Most pro-choice reformers believed the Supreme Court would have to hear an abortion case sooner or later. In fact, the race was on to get a case heard by the Supreme Court. By the time the Court appeal on Roe v. Wade was filed, eleven states across the country had local cases pending, twenty cases challenging state abortion laws were before three-judge courts, and five, counting Roe, were on the docket in the Supreme Court. The Dallas reformers in particular wanted “their” case to be heard.

Coffee and Weddington could only hope that Roe would be chosen. Sometimes their hopes ran high, although in their less optimistic moments they could not imagine that theirs would be the one. Other cases probably had a more fully developed record from the lower court or had included expert testimony, or perhaps they simply presented the issues in a more clear-cut way than Roe did. They fretted that they should not have used anyone but Norma McCorvey as an appellant, and then they buoyed themselves up with the thought that their clients were an unusually well-rounded roster of appellants. But then again, maybe the Court would only hear a case on one of the new, so-called reform laws. It could be used to strike down new and old laws in one blow, if the Court chose to do so.

The opposition was not unhappy with the possibility of a Supreme Court decision. Although they firmly believed that this was an issue best resolved by the states and even though most of the lower court decisions had not gone their way, they could not imagine that the highest court in the land would condone abortion. At worst, they thought the Supreme Court might permit abortions in instances where it was needed to protect a woman’s life and health.

The Court was unusually backlogged throughout 1970, and it was not until early May 1971, near the end of the term, that the announcement came that the Supreme Court was indeed prepared to hear an abortion case. In fact, they had voted four to three to hear two cases: Roe v. Wade and Doe v. Bolton, the latter a case challenging a new reform law in Georgia.

Sarah Weddington, in 1980, accepting an award after speaking at the convention of the National Federation of Democratic Women. (UPI/Bettmann Newsphotos)

Sarah Weddington, in 1979, when she was a senior political advisor to President Jimmy Carter. (UPI/Bettmann Newsphotos)

Linda Coffee, in 1972, shortly after she argued Roe v. Wade in the Fifth Circuit federal court. (UPI/Bettmann Newsphotos)

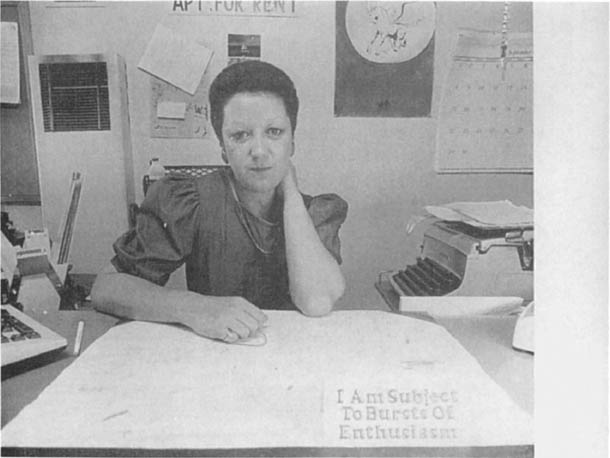

Norma McCorvey, in 1985, in her office where she works as an apartment building manager. (UPI/Bettmann Newsphotos)

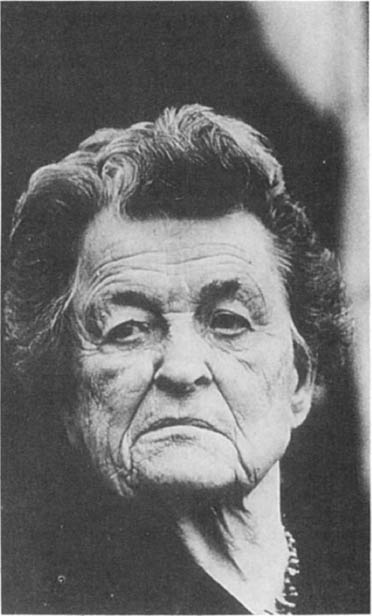

Sherri Finkbine at home in 1962, during the period when she was trying to obtain a legal abortion in Arizona. Finkbine’s request for an abortion when she learned that she might be carrying a thalidomide-deformed fetus played an important role in setting off the nationwide controversy over abortion reform. (UPI/Bettmann Newsphotos)

California physician Dr. Paul J. Shively, left, with his attorney Robert Lamb, during his hearing before the state’s Board of Medical Examiners for illegal abortion. Dr. Shively was placed on probation and Dr. Seymour Smith, the other doctor involved in the case, was reprimanded. The doctors’ case, like Finkbine’s, served to awaken people to the need for abortion reform. (UPI/Bettmann Newsphotos)

Virginia Whitehill, around 1970 when she undertook to reform abortion laws in Texas.

Doris Middleton, who played an active behind-the-scenes role in organizing Texas abrotion reform, in 1987.

Ellen Kalina Lewis was active in the women’s group at the Unitarian Church and later served as the first president of the Dallas abortion reform group.

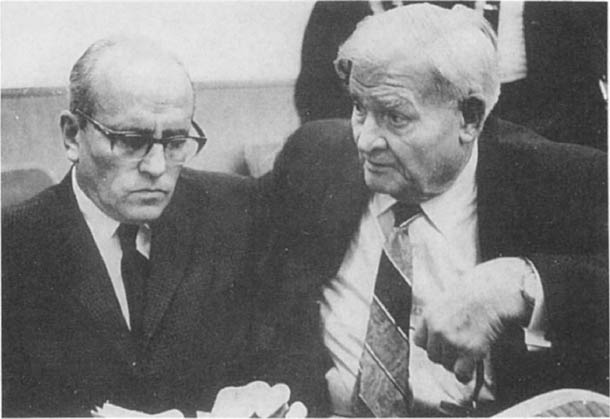

Judges Irving S. Goldberg (1982) and Sarah T. Hughes (1981), Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals. Two of the three judges who heard Roe. v wade argued in 1970 in Dallas. (Randy Grothe/Dallas Morning News)

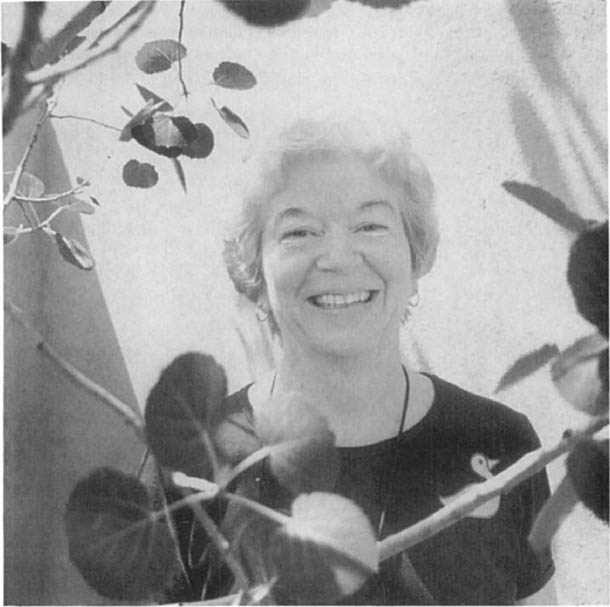

New York University Law School professor Norman Dorsen, a well-known constitutional lawyer who specializes in civil rights, in 1987. He argued Vuitch in the Supreme Court and was the lead lawyer in Roe v. Wade.

Supreme Court Justice Harry Blackmun, center, who wrote the Roe v. Wade opinion, in April 1970, shortly after the announcement of his nomination to the Supreme Court. He is flanked by his sponsors, Senators Walter Mondale, left, and Eugene McCarthy, right. (UPI/Bettmann Newsphotos)

Abortion reform rally, St. Louis, 1970. Across the country women registered their dissatisfaction over present abortion laws with public marches and rallies. (UPI/Bettmann Newsphotos)

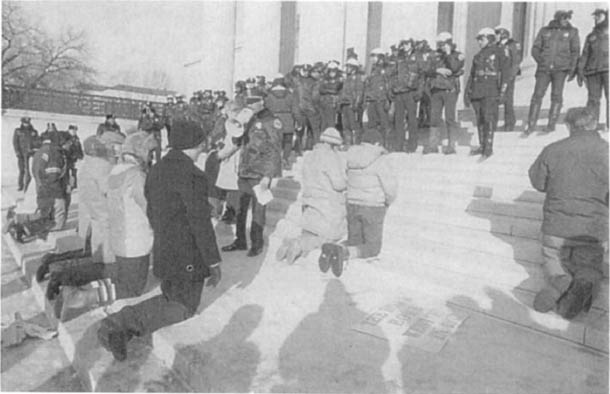

On January 22, 1985, the twelfth anniversary of the Roe v. Wade decision, antiabortion reformers knelt on the steps of the Supreme Court in protest. (UPI/Bettmann Newsphotos)