Everybody is identical in their secret unspoken belief that way deep down they are different from everyone else.

—David Foster Wallace, Infinite Jest, 1996

The psyche of every decade is reflected in its cultural output, and it’s often possible to see in retrospect a fusion of identity to an era. Fashion is an excellent starting point in distinguishing the voice of a generation. On a simplistic level, the 1980s were power-suited, and designer clothes reflected the loads-of-money spiral of consumerism that had taken hold. The postwar 1950s had optimism set into its DNA, and the clothes mirrored this, too, with cheery, cherry-pie-printed dirndl skirts and swishy ponytails. Meanwhile, the rich of the decadent, live-fast 1920s went to parties in fur-lined coats and white-tie ensembles.

The 1990s were about free-form dislocation and the survival of the masses. Dichotomies in fashion flowed easily, from grunge to heroin chic to the gloss of American designer Tom Ford, with his velvet and satin Gucci collection in 1995, to the deconstructive style codes of designer Martin Margiela’s fur wigs and hoofed tabi boots in 1994. Wallace’s writing style, dissecting and delivering a barrage of detail, scrutinized the world around him and anecdotally repackaged it. He said: “Fiction’s about what it is to be a fucking human being.” His fiction was about the multipurpose reality of the 1990s.

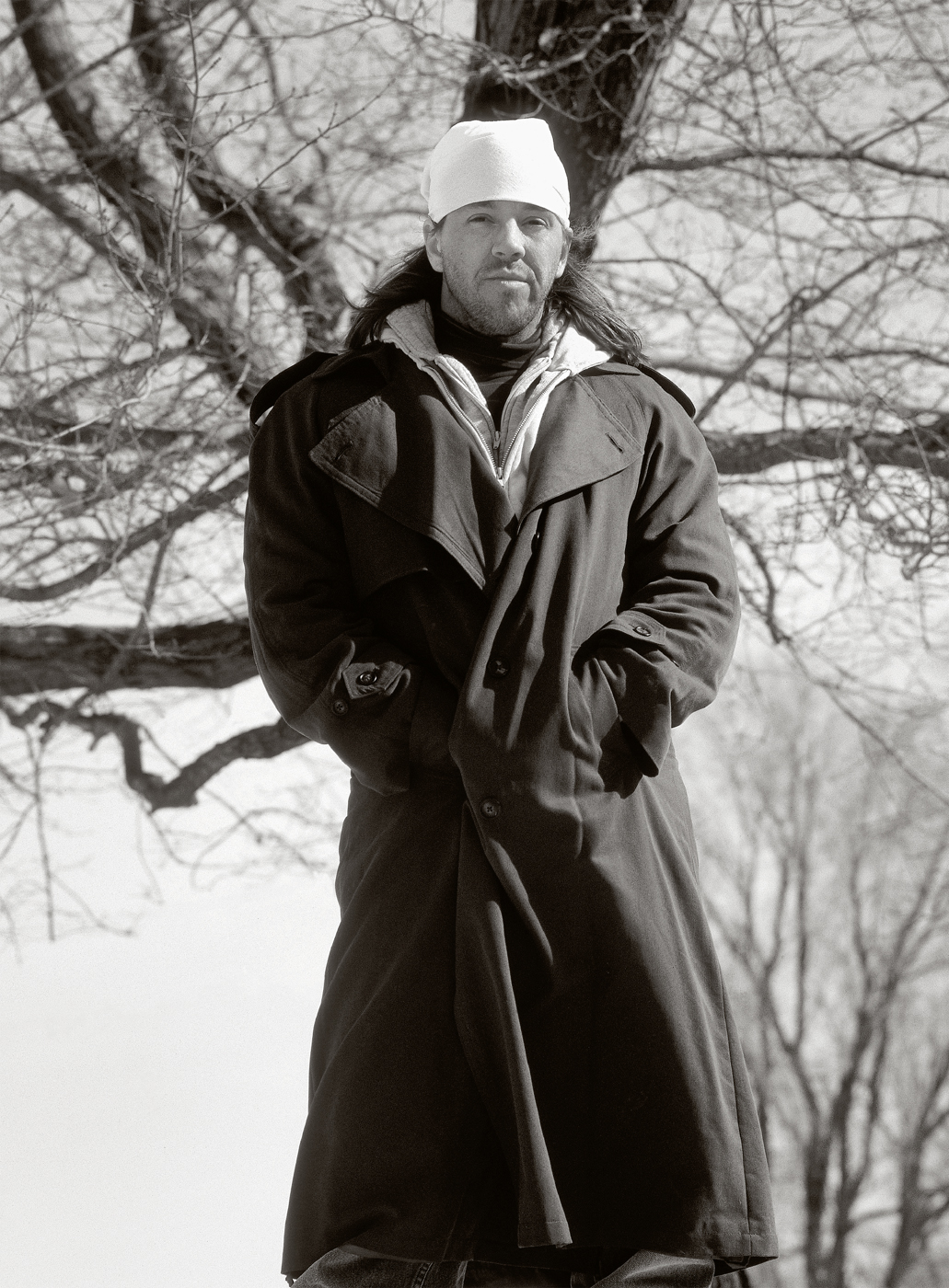

Hannabarger, Gary: © 2016 Gary Hannabarger

David Foster Wallace, Champaign-Urbana, Illinois, 1996.

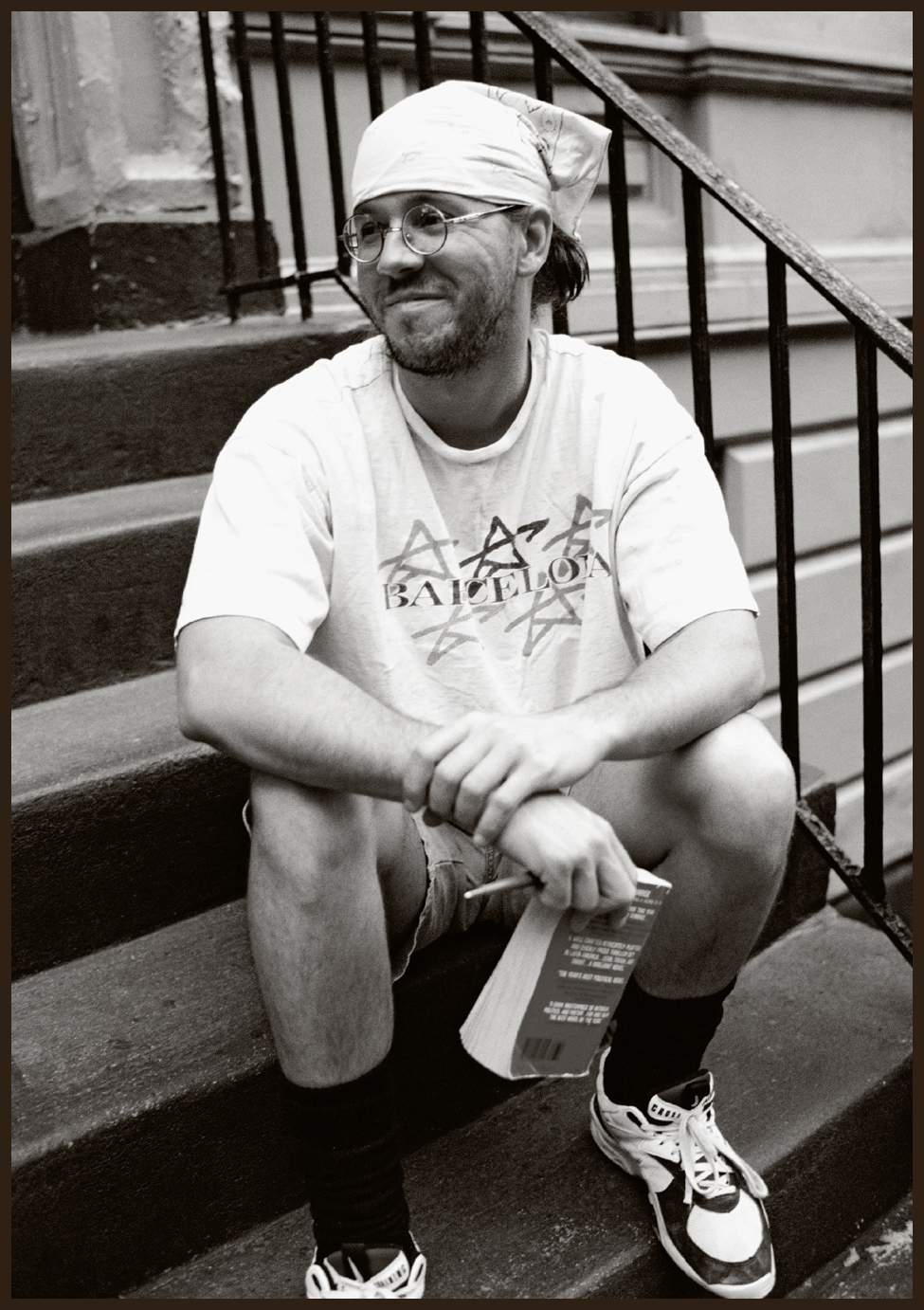

Getty Images: Beckman, Janette

David Foster Wallace, New York City, 2005.

If you worship money and things—if they are where you tap real meaning in life—then you will never have enough. Never feel you have enough. It’s the truth. Worship your own body and beauty and sexual allure and you will always feel ugly, and when time and age start showing, you will die a million deaths before they finally plant you.

—David Foster Wallace, This Is Water: Some Thoughts, Delivered on a Significant Occasion, about Living a Compassionate Life, 2009

Wallace had the sartorial grace of a slacker–skateboarder. His unshaven face, long, greasy hair, rumpled T-shirts, and faded denim jeans were all worn carelessly. He inhabited his clothes. His wardrobe reflected exactly what he was—the literary version of a rock-and-roll star, complete with hell-yeah bandanna. Wallace’s style-setting headwear didn’t come from following the season’s trend forecast from Vogue. Instead, it symbolized the headspace of a thinking, overarticulate, spooked-out writer trying to fathom the world he was living in. It was an extension of his psyche in a way that was entirely sincere, and amid a 1990s world that swiftly became a bricolage of truths, it now seems evocative of Wallace’s solitary mind searching.

There are 577,608 words in Infinite Jest.

David Foster Wallace’s favorite book was The Screwtape Letters by C. S. Lewis.

Wallace grew up in the Midwest, where his home life was comfortable but his mind was turbulent. He was hospitalized, suffering from depression, while at Amherst College, and his first published short story for the college magazine was a semi-autobiographical account of his struggle with the disease. By the time he committed suicide in 2008, he had undertaken twelve sessions of electroshock therapy and attempted suicide once before. He drank, smoked pot, and went to Alcoholics Anonymous. He gave up on his antidepressant prescription of Nardil and eventually found life too hard to bear without medication. His writing was funny, astute, sharp, and painful. He wrote with honesty, and his meta, mega texts were complex and earnest and expressed a yearning for an optimistic alternative.

Green and Mildred Bonk and the other couple they’d shared a trailer with T. Doocy with had gone through a phase one time where they’d crash various collegiate parties and mix with the upper-scale collegiates, and once in one February Green found himself at a Harvard U. dorm where they were having a like Beach-Theme party, with a dumptruck’s worth of sand on the common-room floor and everybody with flower necklaces and skin bronzed with cream or UV-booth-salon visits, all the towheaded guys in floral un-tucked shirts walking around with lockjawed noblest oblige and drinking drinks with umbrellas in them or else wearing Speedos with no shirts and not one fucking pimple anyplace on their back and pretending to surf on a surfboard somebody had nailed to a hump-shaped wave made of blue and white papier mâché . . . Mildred Bonk had donned a grass skirt and bikini-top out of the pile by the keggers and even though almost seven months pregnant had oozed and shimmied right into the mainstream of the swing of things.”

—David Foster Wallace, Infinite Jest, 1996

David Foster Wallace changed prose. And prose gets changed not that often in a century. Hemingway changed prose, so did Salinger and Nabokov. David changed it too. He did an amazing thing. One of the things that writing and speech can do is express what we’re thinking one thought at a time. But we think a thousand things at a time, and David found a way to get all that across in a way that’s incredibly true and incredibly entertaining at the same time. He found that junction.

—David Lipsky, “Getting to Know David Foster Wallace,” 2008