Fashions, being themselves begotten of the desire for change, are quick to change also.

—Marcel Proust, Within a Budding Grove, 1919

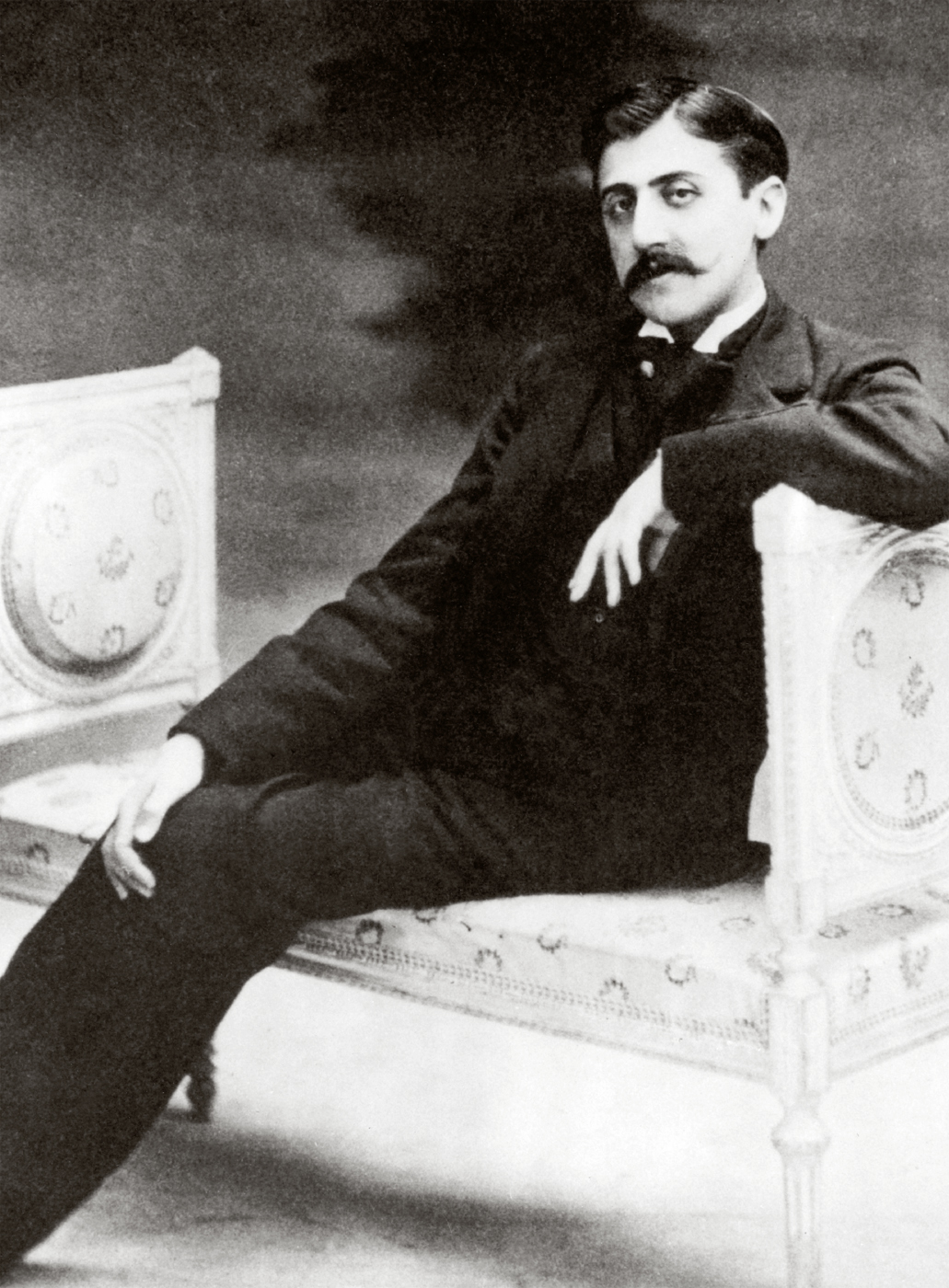

Born in 1871 in Auteuil, a district of Paris, Proust was a belle epoque dandy who wore beautifully laundered white gloves and a cattleya orchid boutonniere, an extravagance purchased daily from the expensive Parisian florist Lachaume on Rue Royale. He observed and embodied the sartorial niceties of the era—his hair was beautifully waved and slicked, and his mustache flourished with the finesse of the time. His ties were secured with a sweeping bow, artistically knotted just on the right side of elegant. He “wore a coat lined with fur” and was said to often wear it to dinner parties. He was regularly spotted with it at the Ritz, having tea.

As a young man Proust suffered from asthma and was generally in poor health, but he suffered with poise. Inspired by the English watercolorist, art critic, and art patron John Ruskin, Proust lived his life to the artistic backbeat of the art nouveau, but his work In Search of Lost Time (À la recherche du temps perdu; earlier translations were called Remembrance of Things Past) has become known as the most important modernist novel of the twentieth century.

Alamy Stock Photo: Colaimages

Marcel Proust, Paris, 1900.

In Search of Lost Time is an exquisite and winding journey into Proust’s soul and mind. It’s a tunnel of an experience for bibliophiles who dare take the challenge of reading the entire seven parts: it’s more than three thousand pages long and meanders around the question of the meanings of life, love, and art. Published between 1913 and 1927 (the last section after Proust’s death), it was a novel that delved into the mind and described thinking. It was also a novel that took the value of clothes and their wispy, otherworldly resonance and incisively assessed their significance.

Proust’s heroine from In Search of Lost Time, Albertine, is said to be based on his secretary, Alfred Agostinelli.

While in prison for theft and petty crime, playwright Jean Genet read Proust and, in 1944, was inspired to write his poetic and fluid novel Our Lady of the Flowers about the underworld of Paris.

In Proust’s early notebooks, he wrote about toasted bread and honey as a memory trigger, rather than the famous madeleines of In Search of Lost Time.

In this novel, Proust mainly depicts fashion in the context of the styles seen in the chicest salons at the end of the nineteenth century, when embellished and impossible elegance was the purpose of design. The finest trimmings and fabrics and the most delicate of accessories, including hats, which were almost always adorned with ever-increasing numbers of feathers and flowers, were the day wear staples of the noble glitterati. Spanish designer Mariano Fortuny created his Grecian column dress, Delphos, in 1907. Made from pleated silk, its pillar like shape was a contrast to the more complicated corseted silhouette of the day. Proust’s description of its aura, in Swann’s Way, is sublime.

Fortuny was of special interest to Proust. He was married to the sister of Proust’s friend Reynaldo Hahn, and his artistic work is used as a metaphor in In Search of Lost Time. The narrator, Marcel’s, adoration of Venice, the sliding sentiment of longing, and the transformation of his lover, Albertine, are all channeled into the clothes Albertine wears. She has a quirky unconventionality, but when “captive” in volume five, she wears designer Fortuny gowns that Marcel buys her because the “best-dressed woman in Paris,” the Duchesse de Guermantes, is a fan. Proust’s use of fashion in this volume is complex and intricate: his attention to fabric, cut, and construction indicates individuality and social position, but also memory and nostalgia.

We do not succeed in changing things according to our desire, but gradually our desire changes.

—Marcel Proust, The Fugitive, 1925

Getty Images: Photo 12

Marcel Proust, Paris, 1905.

Proust is a cult read among scholars and style setters alike, and he is the only author whose designer status has been sanctified by fashion’s own head of the church, Yves Saint Laurent. Saint Laurent designed a number of gowns for Marie-Hélène de Rothschild’s ball celebrating the centenary of the author’s birth in 1971, including a taffeta creation for English actress and musician Jane Birkin. The cream dress had poofy leg-of-mutton sleeves; an enormous bow was tied to the back and edged in lace. It sounds like a monstrous bridezilla horror, but unlike the belle epoque furbelows, it was graceful and easy to wear and looked wonderful as she danced the evening away.

The Fortuny gown which Albertine was wearing that evening seemed to me the tempting phantom of that invisible Venice. It swarmed with Arabic ornaments, like the Venetian palaces hidden like sultanas behind a screen of pierced stone, like the bindings in the Ambrosian library, like the columns from which the Oriental birds that symbolized alternatively life and death were repeated in the mirror of the fabric, of an intense blue which, as my gaze extended over it, was changed into a malleable gold, by those same transmutations which, before the advancing gondolas, change into flaming metal the azure of the Grand Canal. And the sleeves were lined with a cherry pink which is so peculiarly Venetian that it is called Tiepolo pink.

—Marcel Proust, Swann’s Way, 1913