If I have any talent at all, it is not for doing but for being.

—Quentin Crisp, The Naked Civil Servant, 1968

Quentin Crisp’s writing is a legacy of individualism. Of course he wrote about himself—his most significant books are memoirs that are master classes defining the art of the raconteur. Crisp was a cyclone that spins inward—constantly referring to and revealing a painstaking personality that spent years refining its core values. Crisp was unique in his dressing-up skills: what he wore bared his soul—authenticity was at the heart of his look.

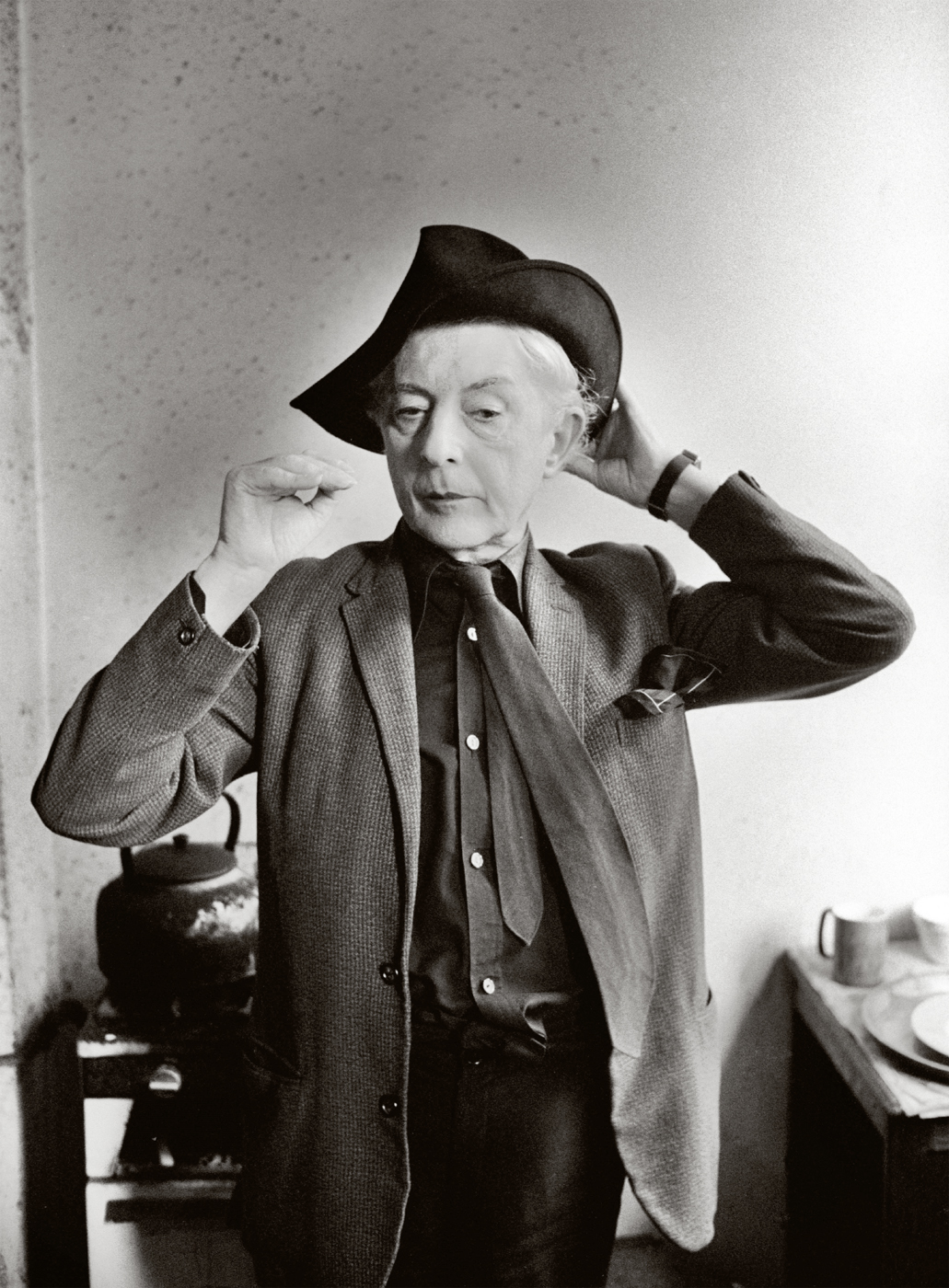

Characteristic Crisp style is embodied by a fedora hat, a silky flowing scarf, a bouffant of dyed hair—red when young, blue as a “stately homo,” as he described himself—and as much makeup as he could layer on. Completely bohemian with a tornado of a twist, Quentin made up dressing-up rules as he went along. Crisp insisted on recognition for what he was: an unashamed gay man. Born in 1908, when he was growing up in suburban England, homosexuality dared not speak its name, but Crisp put on his rouge, hennaed his hair, and brought it up in conversation whenever the opportunity arose.

Alamy Stock Photo: Sykes, Homer

Quentin Crisp, London, 1981.

In the 1930s, Crisp spent his time in London working by day, at an electrical engineering workshop making technical drawings and as a commercial artist and, by night, writing in a studio apartment. By his own admission in his 1968 memoir, The Naked Civil Servant, he had “the airs and graces of a genius” but had yet to find his voice as a writer. Instead, he was more successful in grooming his appearance and indulging seriously in showing off. He wrote: “Exhibitionism is like a drug. Hooked in adolescence, I was now taking doses so massive that they would have killed a novice. Blind with mascara and dumb with lipstick, I paraded the dim streets of Pimlico with my overcoat wrapped round me as though it were a tailless ermine cape. I had to walk like a mummy leaving its tomb. . . . Sometimes I wore a fringe so deep that it completely obscured the way ahead. This hardly mattered. There were always others to look where I was going.”

At age eighty-three, Crisp played the part of Elizabeth I in the 1992 film Orlando.

Crisp always listed his home telephone number, and often encouraged strangers to call him. He always spoke to callers and would go to dinner with them if asked.

By the time World War II began, he had mastered the art of cutting and pasting his wardrobe to fit the one-off character he had become. He explains in The Naked Civil Servant: “In the matter of clothes, I was supported entirely by voluntary contributions, like a hospital, and when introduced to anyone . . . I always looked at their feet to see if they were as small as mine. I hoped their cast-off footwear might be given to me. The trouble with shoes is that they are unalterable . . . I could at any time enlist the services of a certain Mrs. Markham, known throughout Soho as the greatest trouser-taperer in the world. Thus the need to visit men’s-wear shops had been almost totally eliminated.”

Crisp’s feminized style was unique. He wore clothes that twirled around him, edifying his public on the ambiguities of identity. But his intention was not to be taken for a woman, but rather to tread his own inimitable path. In fact, drag bored Crisp. In his memoir, he recounts the story of trying it on for size: “Once, when I lived in Baron’s Court, I traveled by Underground to Piccadilly Circus wearing a black silk dress and some kind of velvet cape. I went to the Regent Palace Hotel, had a drink, and talked airily of this and that with my escort, who was, I think, in a dinner jacket. Then I returned home. The evening was a triumph, in that it was boring; nothing happened. Since then I have never worn drag. Its only effect on me is to make me look less feminine. In women’s clothes even a faint Adam’s apple, even slightly bony insteps, are harshly conspicuous.”

Style is not the man; it is something better. It is a dizzy, dazzling structure that he erects about himself using as building materials selected elements from his own character.

—Quentin Crisp, How to Have a Lifestyle, 1975

Getty Images: Ochs, Michael

Quentin Crisp, circa 1970.

Crisp understood the nuances and code of clothes scrupulously. In 1930s and 1940s England, mainstream menswear was most categorically on the straight and narrow, which of course made Crisp’s wardrobe adventures even more stunning. Even the wrong footwear cast aspersions on an individual’s worth, as he described in The Naked Civil Servant: “To wear suede shoes was to be under suspicion. Anyone who had hair rather than bristle at the back of his neck was thought to be an artist, a foreigner or worse.” Crisp also recollects in this memoir “a friend of mine . . . says that, when he was introduced to an elderly gentleman as an artist, the gentleman said, ‘Oh, I know this young man is an artist. The other day I saw him in the street in a brown jacket.’”

Crisp moved to New York City when he was seventy-two. Despite never becoming a voice for gay rights, Quentin’s decades’ worth of style synchronizing has become an inspirational touchstone the world over. Crisp’s life philosophy was enduring. In 1998 when he was ninety he said: “When you know who you are, you can do it, you can be it, you can be seen to be yourself. That’s the point. You first have to find who you are. Then, you have to be it like mad.”