I write entirely to find out what I’m thinking, what I’m looking at, what I see, and what it means. What I want and what I fear.

—Joan Didion, “Why I Write,” 1976

Joan Didion has told the world the story she wants to live by: she is a style hound who won a guest editorship at Mademoiselle in 1955, then spent ten years at Vogue after securing their notable student writing award, the Prix de Paris. She honed her eye for fashion at the magazine: “In an eight-line caption everything had to work, every word, every comma. It would end up being a Vogue caption, but on its own terms it had to work perfectly,” she explained in an interview with the Paris Review in 1978.

Didion’s style is celebrated worldwide. She was photographed as an icon by Juergen Teller for Céline’s spring 2015 campaign; in 1989 she also took center stage in the Gap’s Individuals of Style advertising billboards. She has been a regular in the pages of Vogue—wearing Armani in 2002 and talking about the nostalgia of clothes in a 2011 feature, in which she reminisces about the dress-up appeal of her mother’s red-velvet, white-fur-collared Patou cape and the childhood fantasies she had of wearing a sable coat, dark glasses, and black silk mantilla. These fantasies have partly come true: “the dark glasses are now most definitely her trademark.”

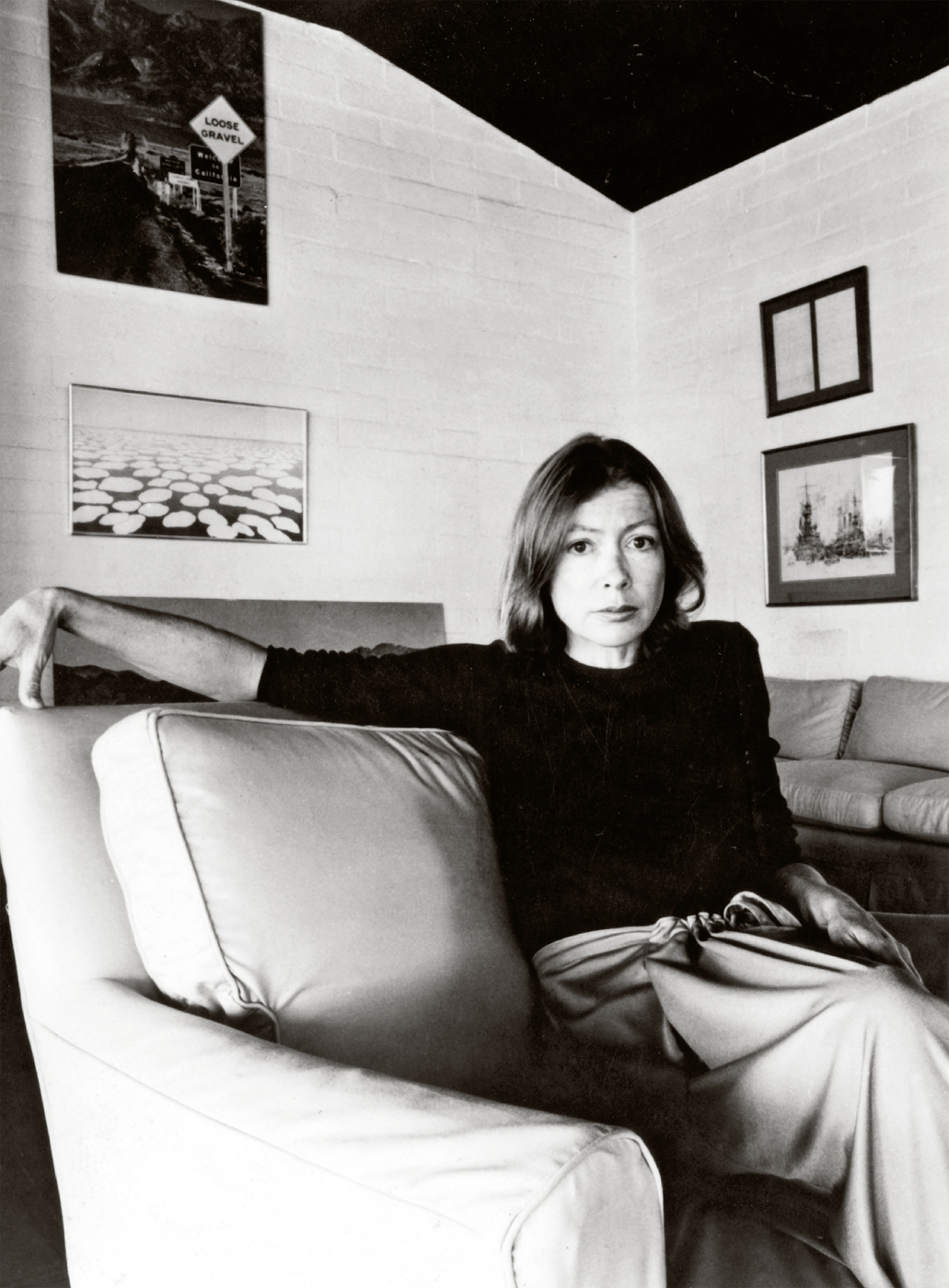

Alamy Stock Photo: Everett Collection Historical

Joan Didion, 1977.

Getty Images: Bryson, John

Joan Didion with her husband John Gregory Dunne and their daughter Quintana Roo Dunne on a deck overlooking the Pacific Ocean in Malibu, 1976.

Casually cool sartorial savoir faire has always been Didion’s byline. Her writing is infused with descriptive analyses of clothing as cultural consideration, and as the years rolled by, her essays have become templates of generational sensibilities. Time and again, she uses the narrative of dress as a structure to explore and examine. In her 1979 collection of essays, The White Album, she talks about her encounter with Manson Family member Linda Kasabian, and as a foil to the horror of the murders, Didion shares the story of buying her a dress to go to court in: “On July 27, 1970, I went to the Magnin-Hi Shop on the third floor of I. Magnin in Beverly Hills and selected, at Linda Kasabian’s request, the dress in which she began her testimony about the murders at Sharon Tate Polanski’s house on Cielo Drive. ‘Size 9 Petite,’ her instructions read. ‘Mini but not extremely mini. In velvet if possible. Emerald green or gold. Or: A Mexican peasant-style dress, smocked or embroidered.’ She needed a frock that morning because the district attorney, Vincent Bugliosi, had expressed doubts about the dress she had planned to wear, a long white homespun shift. ‘Long is for evening,’ he had advised Linda. Long was for evening and white was for brides. At her own wedding in 1965 Linda Kasabian had worn a white brocade suit.”

When she was younger, Didion wanted to be an actress. She said later “I didn’t realize then that it’s the same impulse as writing. It’s make-believe. . . . The only difference being that a writer can do it all alone.”

In the late 1960s Didion had a dog she named Prince Albert.

Didion’s 2005 memoir, The Year of Magical Thinking, written after the death of her husband, John Gregory Dunne, was sadly followed by a 2011 sequel, Blue Nights, in the wake of the passing of their daughter, Quintana Roo. It’s a searching volume that takes the reader through the lawless emotions that materialize when a child dies. Again, Didion uses the metaphor of clothing as memory to fathom a dialogue she can delve into: “There is no drawer I can open without seeing something I do not want, on reflection, to see. There is no closet I can open with room left for the clothes I might actually want to wear. In one closet that might otherwise be put to such use I see, instead, three old Burberry raincoats of John’s, a suede jacket given to Quintana by the mother of her first boyfriend, and an angora cape, long since moth-eaten, given to my mother by my father not long after World War Two. . . . In theory these mementos serve to bring back the moment. In fact they serve only to make clear how inadequately I appreciated the moment when it was here.”

With a typically easy, questioning line, Didion writes with an outsider’s searching consideration of politics, popular culture, sound, and vision: her lucid discussions in print run from the “reverence for water” articulated in her 1979 essay, “Holy Water,” for those who live in parched landscapes such as herself, at a home in Malibu; to the time she recounts in “The White Album” essay published in 1977 how Janis Joplin came to her house in Hollywood and “wanted brandy-and-Benedictine in a water tumbler. Music people,” she reflected, “never wanted ordinary drinks.” Didion intuitively details the disintegration of 1960s idealism and the bitter wariness of 1970s fallout. A 1972 Vogue spread shows Didion with her family near her home in California. She’s wearing a maxi patchwork skirt and pigtails on the beach. Her stylish appeal is even stronger today—international fashion magazines run stories with outfits inspired by her flair and elegance. The Julian Wasser shoot of Didion smoking in front of her Corvette is seminal and a benchmark for serene, laid-back, and blasé poise. Who doesn’t want hair like hers? Who doesn’t want to be skinny and gorgeous like her? Who doesn’t want her ethereal Virgin Suicides–like sensitivity and quirky intelligence? Even now, during her later years, Didion has got the package that the fashion industry craves and copies.

When Didion was working on a book, she would regularly sleep in the same room as her manuscript in order to feel closer to it.

We tell ourselves stories in order to live. . . . We live entirely, especially if we are writers, by the imposition of a narrative line upon disparate images, by the “ideas” with which we have learned to freeze the shifting phantasmagoria which is our actual experience.

—Joan Didion, “The White Album,” 1979