The unendurable is the beginning of the curve of joy.

—Djuna Barnes, Nightwood, 1936

Djuna Barnes’s early life was a cauldron of events that simmered and suckled her turbulent literary work. She was born in 1892 in a log cabin on Storm King Mountain in New York, overlooking the Hudson River. The poetry and rhythm of her life was encapsulated in this visceral starting place; her world was an uneven and testing environment, but it could be exhilarating and beautiful. Barnes’s sinews of survival were stretched instinctively. At the age of five her difficult father, who was a prolific but unsuccessful composer and who rarely earned any money, moved his mistress into the family home. He refused to send Barnes and her eight siblings and stepsiblings to school. Instead, he educated them all himself, helped by Djuna’s grandmother, Zadel, who was a writer, women’s activist, and psychic medium. In her writing, Barnes expressed very little directly about her childhood—instead she provided shades and traces. More concretely, however, she told the novelist Emily Holmes Coleman that her father was “a horror of the first water, what a terrible man . . . Violence, fights and horror were all she knew in her childhood, no one loving her except her grandmother—whom she passionately loved.”

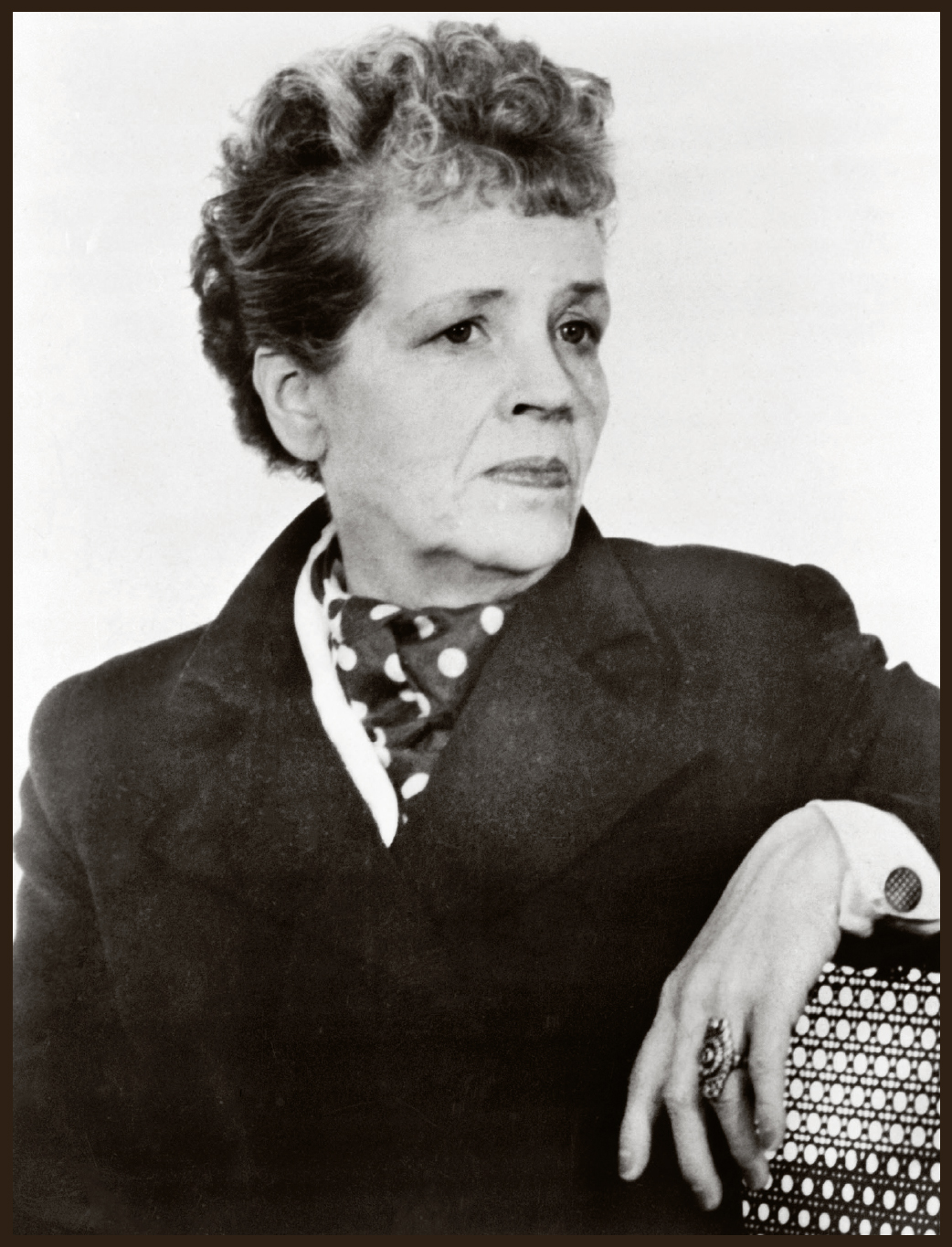

Alamy Stock Photo: Pictorial Press Ltd/Alamy

Djuna Barnes, 1921.

Her father married her off to a much older man when she was sixteen. To escape, Barnes moved to Brooklyn with her mother, the violinist Elizabeth Chappell, and studied at the Pratt Institute for six months before leaving to work as a journalist in order to help with household finances. “You’d be foolish not to hire me,” she professedly told the editor of the Brooklyn Daily Eagle—so they did, when she was twenty-one. Barnes’s experiential approach to news writing went on to generate stories of odd originality, including a New York World magazine feature from 1914 called “The Girl and the Gorilla,” in which she interviewed an ape at the zoo. “My Adventures Being Rescued,” from the same year, recounted what it was like to be saved from a skyscraper.

Inspired by the Suffragettes in England, who went on hunger strikes to bring attention to their cause, Barnes wrote an article in 1914 for New York World magazine called “How It Feels to Be Forcibly Fed.” She went through the agony of force-feeding to understand what it was like in order to complete the feature.

Barnes’s aura and appearance mirrored her skillful and strange approach to writing. In and around the bohemian cafés of Greenwich Village in 1912, Elizabeth Wilson writes in Adorned in Dreams that Barnes was openly laughed at by children who stared in amazement at her striding about in her trademark black cape. Capes at the time were regularly featured in Vogue and a standard for fashionable women. However, it was the way Barnes wore them that counted: overtly masculine and with a flourish of poise and charisma—often topped off with an Alpine hat, trimmed with ribbon. Her effervescent-with-a-twist demeanor is described in a 1919 interview with Guido Bruno for Pearson’s magazine: “Red cheeks. Auburn hair. Gray eyes, ever sparkling with delight and mischief. Fantastic earrings in her ears, picturesquely dressed, ever ready to live and to be merry: that’s the real Djuna as she walks down Fifth Avenue or sips her black coffee, a cigarette in hand, in the Cafe Lafayette. Her morbidity is not a pose. It is as sincere as she is herself.”

In Mary Lynn Broe’s 1991 book, Silence and Power: A Reevaluation of Djuna Barnes, the pianist Chester Page remembers Barnes cutting a similarly magical dash on “a shopping trip to Altman’s on Fifth Avenue, where she was an awe-inspiring figure with her cape and cane and regal posture.” Like many fashionable inspirations, she found a look she liked and kept to it. Andrea Barnet notes in her book, All-Night Party, The Women of Greenwich and Harlem, 1913–1930, that the poet Mina Loy was also in awe of her friend Barnes’s “supreme elegance of clothing.” The friendship between the two modernists caught the eye of American artist Man Ray, who insisted on photographing the kindred spirits in 1920. They turned up for the picture in contrasting black and beige outfits, and, as Ray wrote in his 1963 memoir, Self-Portrait, they “posed as if the camera wasn’t there.” Barnes wore a high-collared cape shrugged onto her shoulders, a silk blouse, and a felt hat: effortlessly elegant. The photographer, Berenice Abbott, was Ray’s assistant and was mentored by him; she went on to take many of the most illuminating images of Barnes. Her pictures show Barnes gracefully tranquil: dressed in tweeds and Lurex, polka dots and lipstick, she was the unflustered flip side to her raging and powerful prose.

Well, isn’t Bohemia a place where everyone is as good as everyone else—and must not a waiter be a little less than a waiter to be a good Bohemian?

—Djuna Barnes, “Becoming Intimate with the Bohemians,” 1916

Getty Images: Bettmann

Djuna Barnes, 1930s.

E. E. Cummings was Barnes’s next-door neighbor when she lived at Patchin Place in Greenwich Village. She lived at number five and he lived at number four. Cummings had a house there from 1923–1982 and Barnes from 1940–1982. Over the years, many writers have lived at Patchin Place, including Theodore Dreiser and John Cowper Powys.

Her 1936 novel, Nightwood, is about the desperate and hopeless, and Barnes makes their conditions so real and immersive that it’s tricky not to be convinced by their bleak evaluation of life. The character Dr. Matthew O’Connor has a diagnostic perception of the world that is both creepy and compelling. He is a seer of the underworld, making sense and nonsense of the creatures he encounters. The novel breezes easily through a realm where unapologetic homosexuality is a fact of life and shifted souls meet and greet the siren call of 1920s Paris with coolly open arms. Trapeze artists, bogus barons and duchesses, bearded ladies, and left children weave in and out of Barnes’s tale. T. S. Eliot compared the work to an Elizabethan tragedy, but Nightwood endures as a modernist collage of thoughts and personalities that search and find as many questions as answers to the dilemma of being alive.