One must be absolutely modern.

—Arthur Rimbaud, “A Season in Hell,” 1873

Articulating the doctrine of a live-fast-die-young youth, Arthur Rimbaud was a libertine who ran away to Paris from his small French hometown of Charleville when he was fifteen. In his famous “seer” letter of May, 1871, he wrote to his friend Paul Demeny that he believed he could only become a “visionary” poet by a “rational derangement of the senses,” which he did with fruitful abandon, throwing himself into a world of constant absinthe drinking and hashish smoking, going around town unwashed and lice-ridden, and embarking on an affair with Paul Verlaine, a poet who was ten years older than he was and who had a pregnant wife. Rimbaud was a compound sum of teenage kicks, the sublime, the gutter, and the beautiful.

Born in 1854, Rimbaud’s story and work became iconic reference for beatniks, hippies, punk-rock-and-rollers and artists more than a hundred years later: his devotees famously include Victor Hugo, who called him an “infant Shakespeare,” Jim Morrison, Patti Smith, the Clash, Henry Miller, and Allen Ginsberg. Rimbaud’s refusal to write any more verse at the age of twenty-one was his final anarchic flourish: instead, he joined the Dutch army, deserted, and finally disappeared to Africa, where he spent the rest of his life in Ethiopia making money doing a little bit of this and that—selling elephant guns, coffee, and spices.

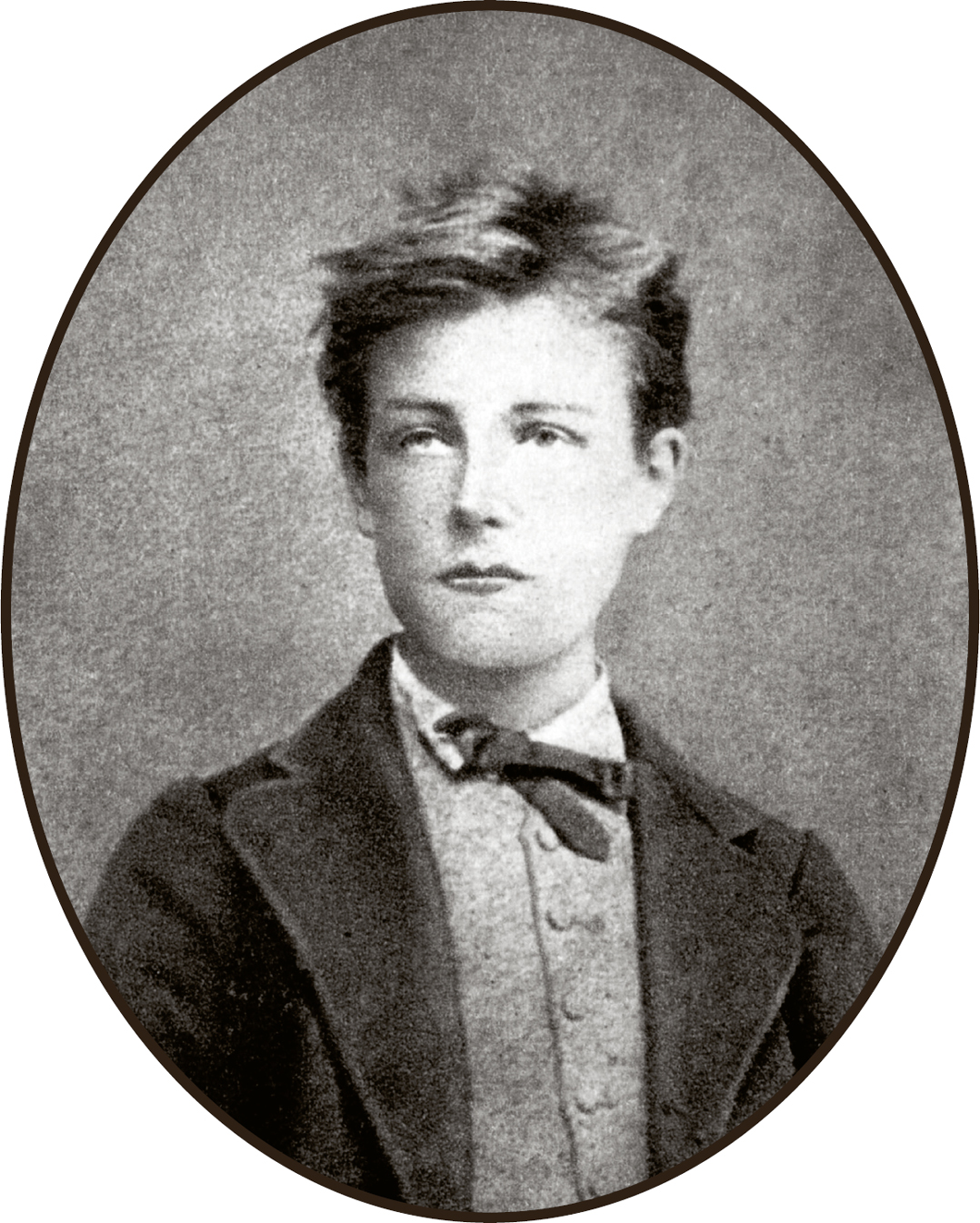

Alamy Stock Photo: The Print Collector

Arthur Rimbaud at sixteen, 1870.

Verlaine saw in Rimbaud a wild and insolent teenager with piercing blue eyes and a reckless nonchalance: all the things that make up the DNA of a Hollywood heartbreaker were wrapped up in Rimbaud’s countrified casualness. Plus, he was a dazzling poet. The two became inseparable.

Rimbaud was a member of the National Guard during the Franco-Prussian War.

Rimbaud wrote the poem “The Seekers of Lice” about the aunts of Georges Izambard, his teacher from the Collège de Charleville, because they used to sit and pick nits out of his hair.

When living in Ethiopia, Rimbaud became best friends with Ras Makonnen, a governor of the Harar district, who was the father of Emperor Haile Selassie, whom the Rastafarian movement believes is God incarnate.

Rimbaud’s poem “My Bohemian Life (Fantasy),” written when he was sixteen, rests for a moment on the role of clothes for the freethinking writer; in tune with Verlaine’s keen grasp of the value of an untidy tangle of an outfit, Rimbaud’s verse celebrates the worth of a deconstructed jacket and a pair of trousers that needs patching. Rimbaud knew that his clothes told the story of him—where he was now, in thought and word and moment. The adolescent bard was nothing if not sincere, and his clothes markedly reflected this. The reason that fashion followers are drawn to grunge and pre-distressed designer wear is because it feels underground—a disheveled look that explodes with the allure of youth and carefree chaos. It’s a fashion statement today, but for Arthur Rimbaud it was the faithful face of an artist.

By age seventeen, he was well on his way to looking the part of the genuine vagabond poet he aspired to be. Wearing a scrawny tatter of a bow tie, he had become a serial runaway and spent time in a prison in Paris for fare dodging and homelessness. Clothes and appearance were an essential part of the vagabond fixation if only insofar as they were as radical and rebellious as he was becoming. “I’m now making myself as scummy as I can. Why? I want to be a poet, and I’m working at turning myself into a Seer. You won’t understand any of this, and I’m almost incapable of explaining it to you. The idea is to reach the unknown by the derangement of all the senses. It involves enormous suffering, but one must be strong and be a born poet. And I’ve realized that I am a poet. It’s really not my fault.”

Idle youth, enslaved to everything; by being too sensitive I have wasted my life.

—Arthur Rimbaud, “Song of the Highest Tower,” 1872

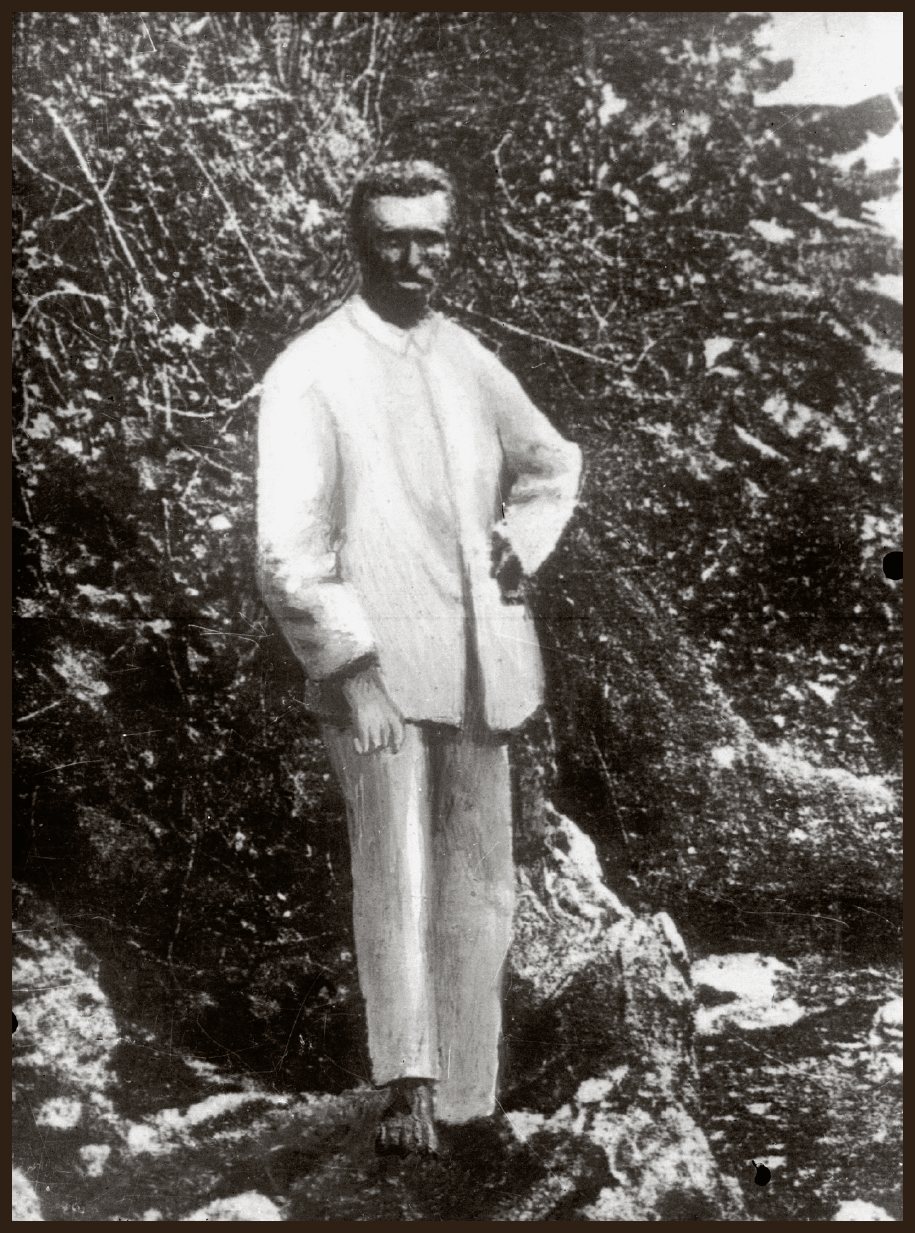

Rex/Shutterstock: Everett Collection Harlingue

Arthur Rimbaud, Harar, Ethiopia, 1883. He moved there reportedly to work as a coffee merchant, but it was really to rest and restore his nervous constitution.

In 1886 Verlaine collated a selection of Rimbaud’s pieces, titled Illuminations. Years later, these opuses would inspire wave after wave of freethinkers: existentialists including Albert Camus and Jean-Paul Sartre, who were drawn to the metaphorical poem “The Drunken Boat”; Dadaists, who would be roused by Rimbaud’s dissent against society; and surrealists, who would champion his embrace of irrationality. The fledgling voice of a sixteen-year-old and all that he conveyed in a fan letter to the poet Théodore de Banville still thrills and provokes anyone who has been a creative outsider: “I’m almost seventeen. The hopeful and dreary age, as they say, and I have begun, a child touched by the muse, sorry if it’s banal,—to express my beliefs, my hopes, my feelings, all those things proper to poets,—I call this spring . . . Ambition! Oh mad ambition!”

Rimbaud’s nickname for his mother was “mouth of darkness” because she was so strict and always trying to keep him in check.