Fashion is what one wears oneself. What is unfashionable is what other people wear.

—Oscar Wilde, An Ideal Husband, 1895

Oscar Wilde had an appetite for beauty that almost literally killed him. Lord Alfred Douglas was the apple of his eye, but it turned sour; at the turn of the twentieth century, their relationship was enough to send Wilde to prison and perpetuate the disintegration of his life and livelihood. Wilde’s wretched end, destitute in Paris—“dying beyond his means”—was hardly a fitting finale for the flamboyant Irish writer and poet who urged in his 1890 novel The Picture of Dorian Gray, “Live! Live the wonderful life that is in you! Let nothing be lost upon you. Be always searching for new sensations. Be afraid of nothing.”

Heedlessly and hedonistically, Wilde embraced life. He was smart, and for a time there was equilibrium when the planet understood him—velvet cape, breeches, sunflowers, silk stockings, and all. He was open-minded and found beauty without cliché in the most unexpected of places; it was this originality that meant, for a time, that he was applauded and audiences found magic in the themes he discussed.

His attitude toward clothing was essentially more pragmatic than history suggests. For Wilde it was never simply a pose, but rather born from a deliberated viewpoint. “The beauty of a dress,” he said in his essay “The Philosophy of Dress,” published in the New York Tribune in 1885, “depends entirely and absolutely on the loveliness it shields, and on the freedom and motion that it does not impede.” He was never a slave to fashion, and one of his most famous quotes, again from the Tribune essay, underlines his wardrobe-wise way of thinking: “Fashion is ephemeral. Art is eternal. Indeed what is a fashion really? A fashion is merely a form of ugliness so absolutely unbearable that we have to alter it every six months!”

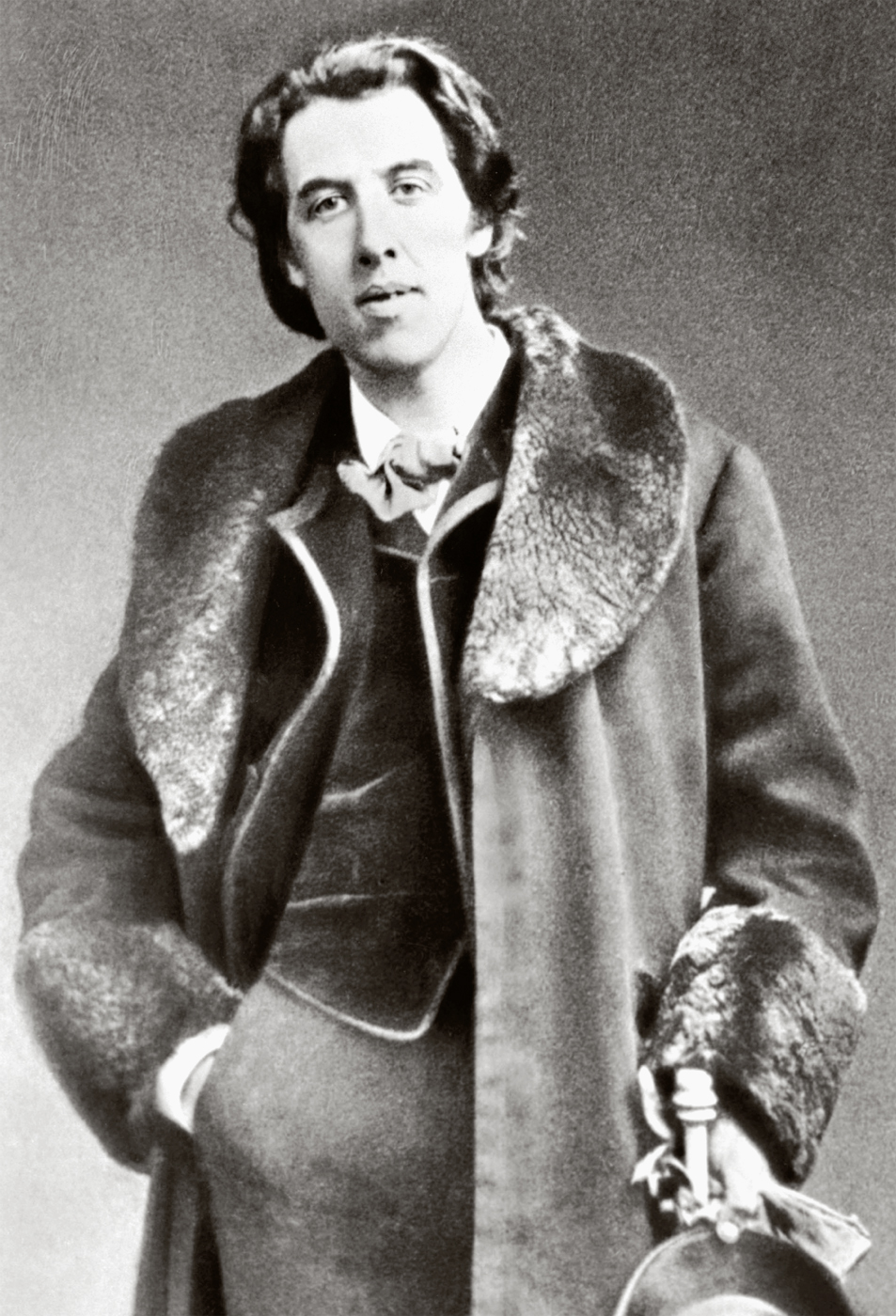

Alamy Stock Photo: SPUTNIK

Oscar Wilde, 1882.

Wilde was a member of the Rational Dress Society, which saw no value in the corsetry and bustles of Victorian England. They asserted that clothing should marry practicality and beauty, and the association fought to release women from the restrictions of the flounces and furbelows of the belle epoque. In the same essay Wilde maintains: “A well-made dress is a simple dress that hangs from the shoulders, that takes its shape from the figure and its folds from the movements of the girl who wears it . . . a badly made dress is an elaborate structure of heterogeneous materials, which having been first cut to pieces with the shears, and then sewn together by the machine, are ultimately so covered with frills and bows and flounces as to become execrable to look at, expensive to pay for, and absolutely useless to wear.”

Before his death at L’Hotel in Paris’s St.-Germain-des-Prés area, Wilde reportedly said: “This wallpaper and I are fighting a duel to the death. Either it goes or I do.”

Wilde always lied about his age, even on his marriage certificate in 1884—he is listed as being twenty-eight, two years younger than he actually was.

Wilde was a heartfelt intellectual, and this, combined with a first-class education at Trinity College Dublin and Oxford, enabled him to articulate with precision an artistic and profound vision, through a body of poetry and words. His dress sense was an extension of his life flow, and as natural as his ability to entertain at the dinner table. For a time, he was the doyen of the Aesthetic movement, known in London society as a wit and an entertaining connoisseur of life. He was friends with Lillie Langtry, the mistress of Albert Edward, the prince of Wales, and one evening in the 1870s the prince invited himself to a séance at Wilde’s house, allegedly with the excuse: “I do not know Mr. Wilde, and not to know Mr. Wilde is not to be known.”

It is absurd to divide people into good and bad. People are either charming or tedious.

—Oscar Wilde, Lady Windermere’s Fan, 1892

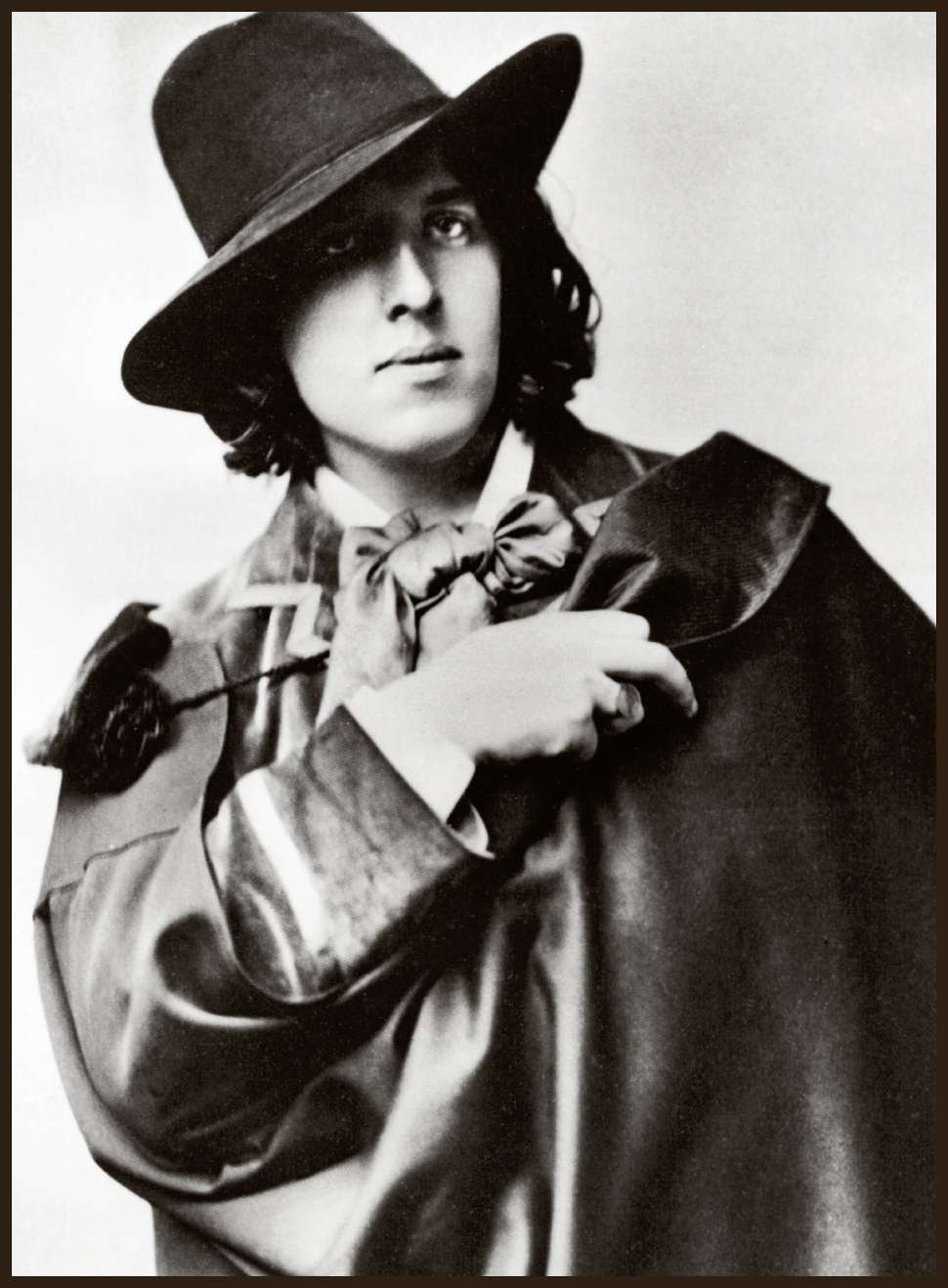

Alamy Stock Photo: Pictorial Press Ltd/Alamy

Oscar Wilde, circa 1880.

The Aesthetic movement he embodied believed in free, unbound expression and revered organic, natural beauty, and Wilde practiced thoroughly what he preached. In the preface to his novel, Dorian Gray, he wrote: “Those who find ugly meanings in beautiful things are corrupt without being charming. This is a fault. Those who find beautiful meanings in beautiful things are the cultivated. For these there is hope.”

In 1882, Wilde reached the high point of his love affair with Aesthetic fashion with the clothing he wore on a trip to America. An 1882 article, “Ten Minutes with a Poet,” in the New York Times described in detail Wilde’s lavish costume: “He wore a low-necked white shirt, with a turn-down collar of extraordinary size, and a large light-blue silk neck scarf. His hands were in the pockets of his fur-lined ulster, and a turban was perched on his head. He wore pantaloons of light color, and patent leather shoes. . . . The only jewelry displayed by him was a seal ring on a finger of his left hand.” The Wildean style was a talking point decades after his death.

No one appreciates more fully than I do, the value and importance of Dress, in its relation to good taste and good health.

—Oscar Wilde, from Constance: The Tragic and Scandalous Life of Mrs. Oscar Wilde, by Franny Moyle, 2012