You never realize how much of your background is sewn into the lining of your clothes.

—Tom Wolfe, The Bonfire of the Vanities, 1987

Tom Wolfe is a dedicated follower of nonfashion. He has paved a sartorial path that is as distinct and knowing as his epic novels and New Journalism writings. He started wearing his legendary and fabulous white suits as a matter of course in 1962 and explained in a 1980 Rolling Stone interview the value of being a square: “When I did The Pump House Gang, I scarcely could have been in a more alien world. I did the whole story in my seersucker rig. I think they enjoyed that hugely. They thought of me as very old. I was thirty-odd years old, and they thought of me as very stuffy. They kind of liked all that—this guy in a straw boater coming around asking them questions. Then it even became more extreme when I was working on Electric Kool-Aid Acid Test. I began to understand that it would really be a major mistake to try to fit into that world.”

Wolfe’s genteel day-to-evening wear of a three-piece cool suit is the presumption of a man who always dresses with a classic twist and gently echoes the tradition and spirit of his hometown, Richmond, Virginia. Wolfe’s fine wardrobe started out as a happy mistake, as he admitted in the 1980 Rolling Stone interview: “I went to a tailor here in New York and picked out a white material to have a suit made for the summertime. Silk tweed is actually a very warm material, so I started wearing the thing in the wintertime. This was the winter of 1962 or 1963, and the reaction of people was just astonishing. . . . The hostility for minor changes in style was just marvelous.” Wearing a white suit suggests the delicate sashay of someone who is not going to get his hands dirty. Dressing in white is a serene and unflappable proposition. Wolfe spent his life as a successful writer sitting on the edge, watching others get embroiled in life.

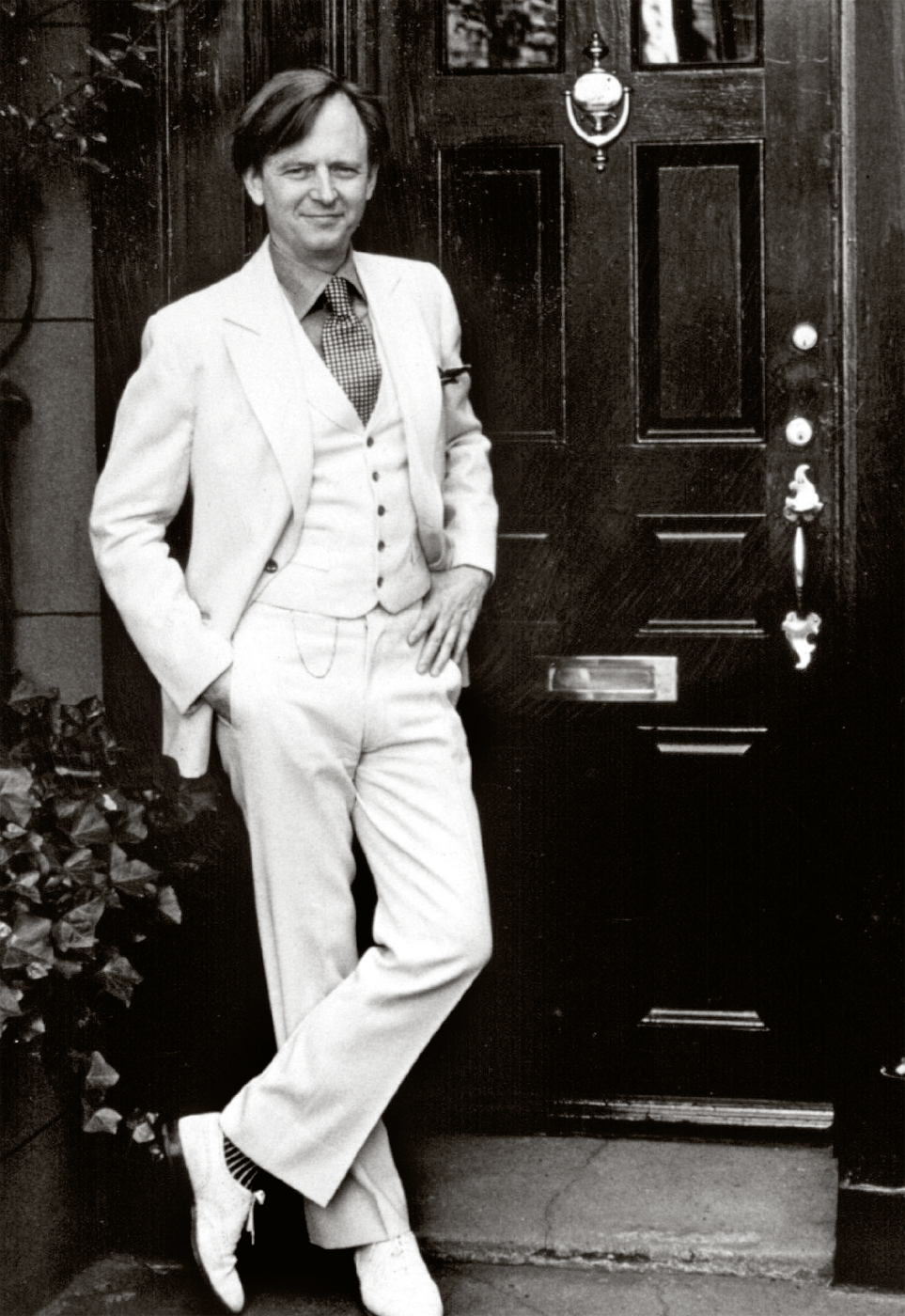

Alamy Stock Photo: Everett Collection Historical

Tom Wolfe, circa 1980.

The New York Public Library bought 190 boxes of notebooks, letters, tailor’s bills, Christmas cards, drawings, and manuscripts from Wolfe for more than $2 million. He said it made him feel “very important.”

The only other career Wolfe considered, apart from being a writer, was to become an artist.

When in the middle of a piece, Wolfe sets a target of writing ten pages a day—approximately 1,800 words.

In Wolfe’s writing, the devil is in the fascinating detail. And this is exactly how he sees value in his wardrobe. “The Secret Vice” was an essay he wrote for the New York Herald Tribune in 1966 in praise of “real buttonholes” and properly tailored suiting. Likewise, in his literary work it’s not just the component parts of his characters’ lives that are meticulously researched and held up for scrutiny: more often than not, their clothes are, too.

The psychology of modern Western life is wrapped up in consumer culture, and identity is frequently disclosed by dress. Wolfe delves into these rudiments in his writing, and in a 1991 interview in the Paris Review, he said: “I realized instinctively that if I were going to write vignettes of contemporary life . . . I wanted all the sounds, the looks, the feel of whatever place I was writing about to be in this vignette. Brand names, tastes in clothes and furniture, manners, the way people treat children, servants, or their superiors, are important clues to an individual’s expectations.”

Dark observation of casual dress is a classic Wolfe technique. His own closet of canes, homburg hats, spats, and coordinating vests are at direct odds with a culture of dressing down. Wolfe clocks casual and dissects it in The Bonfire of the Vanities, using casual dress as a frenzied contrast to the ostentation of his Wall Street bond trader character, who calls himself the Master of the Universe. Sherman McCoy wears a “formidable rubberized British riding mac, full of flaps, straps and buckles . . . he had considered its aged look as just the thing, after the fashion of the Boston Cracked Shoe look.” In comparison, travelers on the D train wear cheap sneakers: “Half the people in the car were wearing sneakers with splashy designs on them and molded soles that looked like gravy boats. Young people were wearing them, old men were wearing them, mothers with children on their laps were wearing them. . . . On the D train these sneakers were like a sign around the neck reading SLUM or EL BARRIO.”

Real buttonholes. That’s it! A man can take his thumb and forefinger and unbutton his sleeve at the wrist because this kind of suit has real buttonholes there.

—Tom Wolfe, “The Secret Vice,” 1966

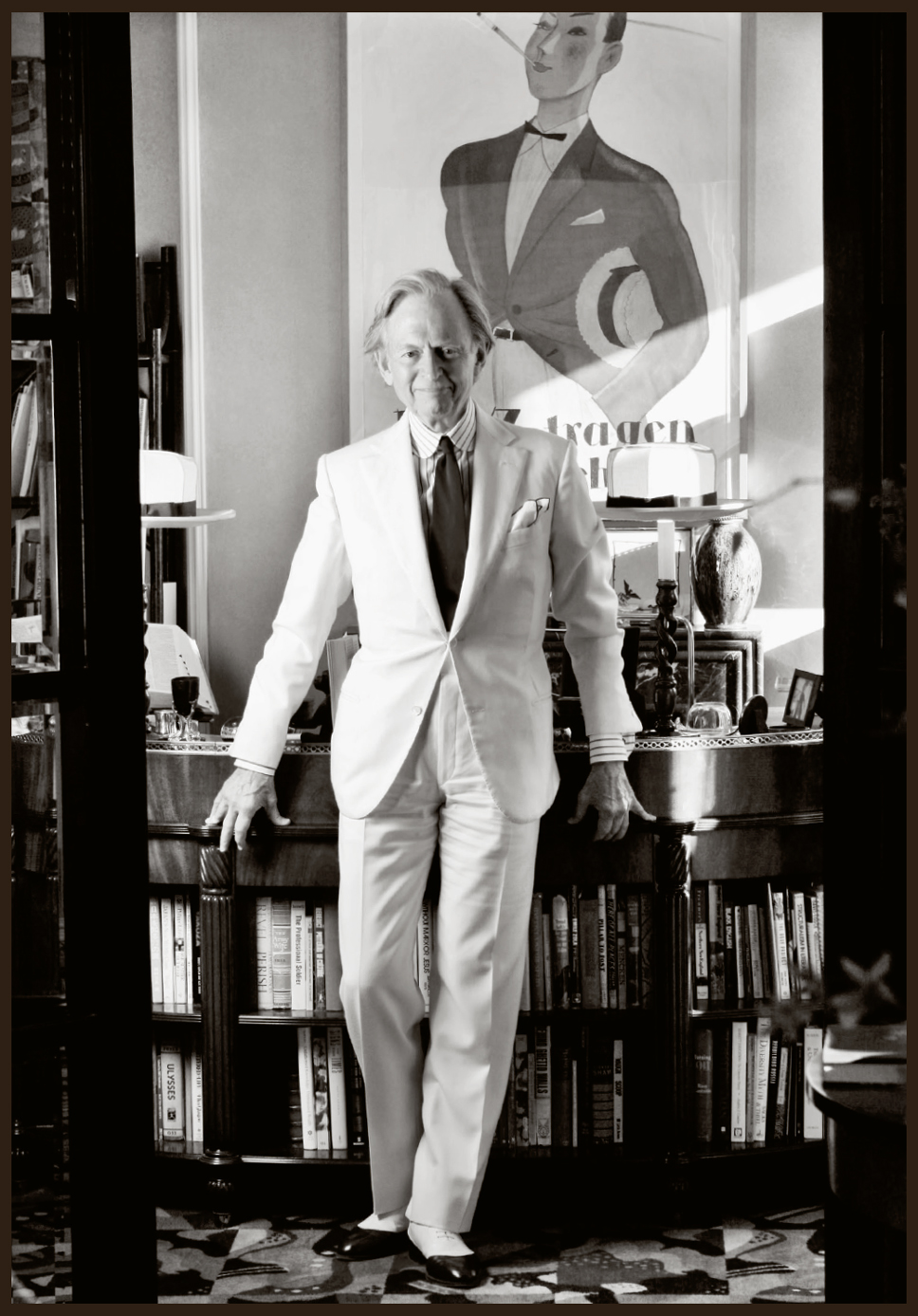

Alamy Stock Photo: Callister, Dan

Tom Wolfe at his Upper East Side apartment, New York City, 2004.

In Wolfe’s 1970 article for New York magazine, “Radical Chic: That Evening at Lenny’s,” he satirizes the elegance of Park Avenue with a feature documenting a party given by the conductor Leonard Bernstein for his well-heeled friends in aid of the Black Panther cause. The minutiae of the moment centers on what is being worn.

The Panther women . . . are so lean, so lithe, as they say, with tight pants and Yoruba-style headdresses, almost like turbans, as if they’d stepped out of the pages of Vogue, although no doubt Vogue got it from them. . . .

What does one wear to these parties for the Panthers or the Young Lords or the grape workers? What does a woman wear? Obviously one does not want to wear something frivolously and pompously expensive, such as a Gerard Pipart party dress. On the other hand one does not want to arrive “poor-mouthing it” in some outrageous turtleneck and West Eighth Street bell-jean combination, as if one is “funky” and of “the people.”

—Tom Wolfe, “Radical Chic: That Party at Lenny’s,” 1970