An invisible structure exists in American society that operates to maintain the status quo.”

An invisible structure exists in American society that operates to maintain the status quo.”Reframing Your Thinking

We are all captives of culture.

—EDWARD T. HALL, PHD, ANTHROPOLOGIST

In spite of what we might like to believe, the culture of any given organization does not spontaneously or mysteriously develop. The founders of an organization instill their company culture with their values, beliefs, and assumptions. The learning experiences of the first employees—people who share the vision of the founders, believe in the mission, and are willing to assume the risks—also serve to inform the developing culture, but it’s the founders who impact and influence culture the most. This first group of employees, led by the founders, effectively sets up the process of culture formation.

Informed by the vision and mission of company leaders, teams typically begin to seek funding, secure workspace, build products, develop services, and do the work that’s needed to grow and manage a new company. As more people are hired, the history of the organization begins to take hold, and the vision and mission of the company’s leaders become embedded in the values, beliefs, and assumptions of the founding group. Basically, at this point, they’ve established the corporate norms and the accepted way of doing things.

Looking at Your Organizational Culture

In sociology, a norm is known as an established standard of behavior, shared by members of a group, that each member of the group is expected to conform to. In business organizations, norms are informally taught to employees when leaders socialize the norms, act with confidence on them, and make decisions based on them.

Although company norms aren’t documented as a part of the developing culture of a company, they are profoundly influential.1 This is because the values embraced by an organization are implicitly governed by the norms of the founders; and as a result, employees are expected to act on those values.

As you think about how to develop, inform, or transform your organization, it’s important to realize that fully effective leaders of an organization understand the business and human value of developing diverse and inclusive workforces. It wouldn’t occur to these kinds of leaders to develop a company in any other way. Does your company have leaders who place value on a diverse and inclusive workforce? Have they set up norms in your company that support and sustain a culture of inclusion?

Building a Culture, Creating a Legacy

Kaiser Permanente (KP), one of the largest integrated healthcare systems in the United States, was founded in the early 1940s as the result of a collaboration between industrialist Henry J. Kaiser and physician Sydney Garfield. In its earliest beginnings, the Kaiser shipyards of World War II employed the first women to help build American ships in an industrial setting. By 1944, women accounted for 35% of the shipyard workforce. Kaiser next established the first on-site, company-sponsored child-care centers in the United States, and then throughout the 1940s they hired an estimated 20,000 African-Americans, Chinese-Americans, Native Americans, and Latinos. In 1943, two decades before Civil Rights legislation was even passed, the Permanente Foundation Hospitals refused to discriminate, offering all its employees the same check-ups and quality of medical attention from KP doctors, regardless of gender or race. Even more, the KP public health plan took the lead in equal treatment of hospital patients in 1945, refusing to segregate them by color.

As the founders of KP, Kaiser and Garfield built an organizational culture that was progressive and innovative in the 1940s, showing that they not only valued diversity and inclusion but were also willing to take risks to make it happen. The corporate norms and organizational values of diversity and inclusion, embedded by the KP founders, continue to inform the award-winning culture of KP today.2

Truly inclusive leaders break from past norms, take risks, and champion a culture of diversity in their organizations. They don’t make statements we sometimes hear people say, like “I’d hire them, but they’re just not there,” “It’s going to take a long time to correct the diversity problem here,” or “Changing the educational system is the real problem.” They don’t make excuses, shift responsibility to someone else, or shrink away because the work is hard. Inclusive leaders understand the essential value in diverse work environments and summon the courage to proceed toward that vision.

We’re all learning how to establish diversity in the context of different workplace cultures, and sometimes this requires that we develop certain skills. But the goal is to have leaders in place who embody certain key qualities, whether they possess these qualities intuitively or they learn how to attain them. Inclusive leaders are people who:

DO YOU HAVE AN INCLUSIVE LEADER?

Want to find out if your leader is inclusive? Here are a few things you can do:

1.Start by asking a couple of simple but vitally important questions: Is your company leader trustworthy? Would customers, suppliers, and employees across organizational levels describe the leader this way? Trust is perhaps the single most pertinent characteristic of an inclusive leader because it is something that is earned, not given. Inclusive behaviors cannot be faked; even false pretenses of inclusivity reek with the smell of insincerity. If a leader acts with inclusive behaviors, that is someone who is typically trusted in a company.

2.You can also observe the actions and consistent behavior patterns of your leader. Is your leader genuinely open to input? Does this person respond to feedback from employee surveys, communicating that he or she has heard the workforce, is prepared to take action, and will share the results of those actions? These behaviors show that a leader is a person who cares about the differing perspectives of others, listens actively, and responds with action and transparency. Does your leader facilitate dialogue with curiosity and a desire to understand? These are traits and behaviors you want to see in an inclusive leader.

3.Take the test developed by the Catalyst organization to measure inclusive leadership. Here’s the link: www.catalyst.org/knowledge/quiz-are-you-inclusive-leader.

Norms, Values, and Mental Models

Edgar Schein, former professor emeritus at the Sloan School of Management at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, is a pioneer in the field of organizational development. For decades he’s been widely recognized as one of the leading thinkers on the topic of organizational culture and leadership. He says organizational culture, which emanates from a company’s founders, has three components. According to his definition, organizational cultures are built from:

1.artifacts, or what you experience with your senses (language, styles, stories, and published statements, like vision and mission placards);

2.espoused beliefs and values (ideals, goals, and aspirations); and

3.basic underlying beliefs (taken for granted and not questioned/discussed).3

Organizational culture is like the speed of light—it’s impossible to change. When organizational leaders say, “We need to change the culture around here,” what they’re really saying is that they desire behavior change. Maybe they want managers to attend meetings on time or they want employees to be more customer-centric. These types of behaviors can often be altered by changing structure; leaders can introduce new policies or put reward systems in place, for example.

Other behavior changes, such as those needed to increase the amount of diverse talent in the organization, however, involve first identifying the underlying influences that reinforce existing behaviors. But becoming a more equitable, inclusive, and diverse organization requires a mindset shift that involves an intentional movement away from being less self-conscious to becoming more interaction-conscious.

This is extraordinarily challenging, particularly for US-based companies, since this kind of mindset shift runs counter to the highly individualistic American culture. To change a company in this way asks us to go up against our accumulated learning, which is based on everything we’ve learned and experienced individually, in groups, and throughout a company up to that point.

Understanding the norms, values, and mental models (lenses through which each person sees the world) upon which the founders of your organization built your company is essential, since these directly affect the way people in the organization interact as well as the people who might even be asked to join the organization. As you think about bringing change to your organization, understand that organizational culture represents the collective values and beliefs of a larger group; it implicitly governs appropriate behavior for various situations, including how people behave toward others who are different from them.

To appreciate and understand the influences that strongly impact the leader(s) of your company, ask questions. Instead of asking about workplace issues or concerns, ask what life—not career—advice they would give to others or to you. Ask them what life advice they wish they had received themselves. Ask them about people who influenced them. Then you might begin to see the world and the company through the lens of the leader(s).

A Framework for Thinking about Differences

I once suggested to a group at a large, established organization that they should consider developing a separate leadership program just for women. One of the senior leaders of this company, a white male, responded, “We don’t need that. Sure, there are women who need help advancing in their careers, but there are plenty of men—including white men—who need help, too.”

He was correct. But here is what he didn’t acknowledge: an invisible structure exists in American society that operates to maintain the status quo. It is akin to hidden organizational norms; only in this case, we’re talking about societal norms.

An invisible structure exists in American society that operates to maintain the status quo.”

An invisible structure exists in American society that operates to maintain the status quo.”

Societal norms enable some people to move through life with ease and require others to work much harder to move forward. To be effective at developing diverse, inclusive work environments, we have to be willing to accept that this framework has influenced all of us—even people like me, who were taught to treat everyone with fairness and respect; even people who were raised in multicultural environments where they learned to embrace distinctions among people. Every person who is good-hearted, compassionate, and well-intentioned has still been shaped and influenced by the issues affecting equity, inclusion, and diversity. We are all complicit in keeping invisible forms of discrimination alive, regardless of our good intentions. The forces are invisible but powerful.

Every person who is good-hearted, compassionate, and well-intentioned has still been shaped and influenced by the issues affecting equity, inclusion, and diversity.”

Every person who is good-hearted, compassionate, and well-intentioned has still been shaped and influenced by the issues affecting equity, inclusion, and diversity.”

To enable you to take a closer look at the ways in which issues of equity, inclusion, and diversity influence and inform the society in which we live and work, consider the following chart.4

When we acknowledge that we have been shaped by the beliefs that enable the above framework, we position ourselves to become less defensive and more understanding of the opportunity to use this framework to guide meaningful dialogue about workforce effectiveness, diversity, and the sense of belonging that is inclusion. This is the beginning of becoming a more culturally effective person—and of understanding that a system of unearned advantage is a longtime structural institution that impacts our conscious and unconscious beliefs and behaviors.

As an example, prior to the Americans with Disabilities Act, not much thought was given to the challenge of entering a building or a bathroom in a wheelchair, because most people are able-bodied. The Disability Implicit Association Test shows that 76% of people have a hidden preference (bias) for able-bodied persons.5 Similarly, the senior male leader mentioned earlier has never experienced the challenge of being female, since that has never been the lens through which he views the world. So this means that it’s essential for each of us to understand our places in the framework of differences.

Those of us who go through life accepting things without question often behave in ways that assume what is true for us is also true for everyone. It takes humility to admit that some groups have it much easier than others based on variables none of us control. And it takes courage to act on this. Consider these scenarios:

When we choose to act, we use our privilege to make our workplace, society, and the world a better place for women, minorities, and other extraordinary people.

When we choose to act, we use our privilege to make our workplace, society, and the world a better place for women, minorities, and other extraordinary people.”

When we choose to act, we use our privilege to make our workplace, society, and the world a better place for women, minorities, and other extraordinary people.”

In a study of identical resumes, one with a man’s name and one with a woman’s name, the study found that 79% of applicants with the man’s name versus 49% of those with the woman’s name were considered “worthy of hire.”6 This means that for all of us, reflection and deliberate intention are required in order to see systems as they truly are; until we do this, we won’t be able to change them.

As we uncover our hidden biases, practice self-reflection, and grow in our curiosity about others, we can begin the process of writing what I call “mental prescriptions” to help keep ourselves in check. A feeling of discomfort in the company of people who are not like me is a normal feeling. When these instances occur, the mental prescription is a reminder that the sense of discomfort is about me, the person experiencing the uneasiness—not about the person(s) I am with.

Mental Prescriptions

Mental prescriptions are messages we create for ourselves to practice new ways of thinking—reframed thinking. When we think positively, we give others the benefit of the doubt. That is, we start from a place of assuming good, rather than bad, things about people or their actions.

When we’re driving on the freeway and another person tailgates us, we may go negative and get annoyed, upset, or angry. We may think: “What’s wrong with them? What’s the big hurry? What a reckless driver!” and similar thoughts that typically run through a person’s head.

Now, however, when someone tailgates me on the freeway, I try to move out of the way and let them pass. The mental prescriptions I write for myself say, “Perhaps they are nearsighted and overdue for an eye exam,” or “They could be rushing their child to the emergency room.” I try to come up with a thought that allows me to be sympathetic or amused, something that enables me to give this person the benefit of the doubt. The reality is that I don’t know why they are driving so closely behind; they could in fact be reckless. But I can’t control their actions. I can only control my response.

So how do mental prescriptions apply to workplace diversity? My friend and colleague Sam is a highly educated, accomplished African-American woman and corporate diversity strategist. She once facilitated a challenging discussion with a group of white men, trying to get them to own the privileges bestowed on them by society. She called me afterward to share her mistake in taking this approach and feared having done harm. When the men left the discussion that day, they were angry at the suggestion that they were somehow responsible for workplace discrimination and social injustice. Sam wrote herself a mental prescription. It said, “If I had entered the room giving the benefit of the doubt to those men—perhaps they are not even aware of systemic inequities—I may have had greater success in getting them on board to help fight inequality at work.” Sam’s truth is that she experiences daily aggressions directed at her as a Black woman. But her anger at this injustice is about her, not about them.

Learning to write mental prescriptions requires that we use critical-thinking skills. This means we need to be people who think for ourselves. We need to raise important questions, gather relevant information, think open-mindedly, and consider alternative views. We need to recognize and assess our assumptions and also consider both the practical and potential unintended consequences of these assumptions. Critical thinking is a skill set people develop with a lot of practice over time. We need to learn how to do this well if we ever want a chance at really changing the reality of hidden discrimination in our workplaces.

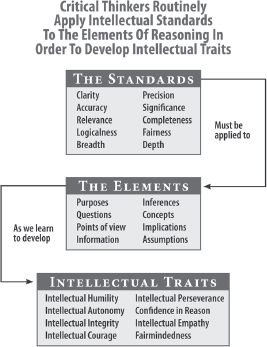

Individuals with a well-developed capacity for critical thinking possess what are sometimes called intellectual traits. This does not imply that an advanced degree is required to learn to think critically. To be clear, credentials have nothing to do with the ability to think critically. Anyone who is curious and has a desire to learn and to develop a stronger understanding of a topic can develop critical-thinking skills. Critical thinkers are people who act with courage, show empathy, possess humility, and are fair-minded. They have integrity and have mastered the ability to think for themselves. To develop these traits, they apply elements of reasoning. They ask questions and consider implications and assumptions. They evaluate the purpose of a discussion or topic and look at different viewpoints. Their reasoning is guided by a desire for clarity, precision, accuracy, and relevance. And they care about fairness and seek to understand issues beneath the surface.

I think of critical thinkers as people with enlightened traits. We are using critical thinking when we hear or see something and decide to suspend judgment so that we can check to see if it’s valid; when we take multiple perspectives into consideration; when we consider the consequences of an action or the implications of things we believe; when we use evidence as a basis for decision-making; and when we reevaluate a viewpoint or belief in light of new information.

The three dimensions of critical thinking defined by the Foundation for Critical Thinking are shown as follows.7

From “The Miniature Guide to Critical Thinking, Concepts and Tools,” by Dr. Richard Paul and Dr. Linda Elder, 7th Edition. Copyright © 2014 by the Foundation for Critical Thinking, www.criticalthinking.org.

All rights reserved. Reproduced by permission of the Foundation for Critical Thinking.

What does all this mean? As humans, we have the built-in tendency to believe things as we perceive them to be. We usually view ourselves as objective and feel pretty confident about our beliefs. We see our ideas as meaningful because we’ve always believed them to be true, we want them to be true, or it’s in our interest for them to be true. This winds up being an egocentric kind of thinking that’s largely done without any objective questioning. It’s a natural thing we all do.

Similarly, in groups and societies we tend to position our norms, cultures, and even religions as more valuable than those of others. We act in the way we are expected to act, not questioning or considering differences among others. This is a socio-centric kind of thinking that’s profoundly supported by mass media, particularly social media, and it constrains us to the viewpoints of our own society and groups. Like egocentrism, we also tend to do this naturally and innately.

All of us regularly engage in these two less-than-rational ways of thinking. And while being egocentric and socio-centric are natural conditions in human development, critical thinking works differently and occurs when we actively and intentionally develop our skills in it. Author and creative innovator Scott Berkun says there are two questions that should be asked wherever people gather—in schools, meeting places, cafes, and anyplace where thinking for oneself is advocated:

Why do we believe what we believe?

How do we know what we know?8

There are courses that teach the art of debating, and the best of these take learners far beyond the ability to form a position, present evidence, or respond to objections. Optimal learning and speaking skills come when we are required to defend the opposite position, the one that runs counter to our true opinions or beliefs. It’s healthy for us to consider not just our own views but also counter views. As well, when engaged in debate, Berkun suggests we try asking people:

Who, besides you, shares this opinion (or point of view)?

What are your major concerns, and what actions will you take to address them?

What would need to change for you to develop a completely different (opposite) opinion?9

If we want organizations that are multidimensional, inclusive of differing viewpoints, and fair to all, then we need to encourage people to think for themselves, reward open-mindedness, and act in ways to show that the rights and needs of every worker are equal to our own.10 Critical thinking does not occur naturally; it must be taught, fostered, developed, and rewarded. This active cultivation combats irrational tendencies and activates the ability to write mental prescriptions in support of progressive, diverse workplaces that will drive future success. It also quite literally expands our brain-processing power.

Follow me on this. The brain’s ability to reorganize itself by forming new neural connections is known as neuroplasticity. From the moment we arrive into the world, we begin developing a belief system. As newborn babies, since we lack a developed capacity for rational, logical deduction, our first beliefs are based on our experience of the world. As we grow and mature, our skills, knowledge, abilities, and understanding of the world expand. Our brains are constantly developing new and often stronger (based on length) neural connections, and in effect are reorganizing based on our new experiences.

Undertaking new experiences enables us to grow, learn, and effectively change the shape of our brains.11 And new experiences enable us to push past the common binary categories we too often use—young and old, gay and straight, black and white. With gender, we assume people to be either male or female, thereby excluding individuals born intersexed (genitalia not definitively male or female). Exclusion minimizes people and makes them less visible. This then leads to them not getting the rights they deserve as humans. In politics, we focus on conservatives versus liberals and lose the value that independent, moderate views could bring to addressing national and global issues. New experiences provide the opportunity for us to reorganize our thinking, which betters us individually and the world collectively.

DISTINGUISHING CONSCIOUS FROM UNCONSCIOUS

The reflective system, or conscious mind, represents 10% of our brainpower, which thinks, plans, analyzes, and controls shortterm memory. The reflexive system, or unconscious mind, represents the other 90% of our brainpower, including long-term memory, emotions and feelings, habits, relationship patterns, addictions, creativity, and intuition.

Our conscious mind takes certain actions, while our unconscious mind is the automatic system responsible for keeping us safe. When we’re tired, stressed, frustrated, annoyed, or threatened, these emotions overtake our reflective control mechanisms, and our unconscious biases are triggered to take over our conscious behaviors.12 This automatic triggering can be both helpful and hurtful. It’s useful, for example, when I’m exhausted and working late in the office, and without conscious thought, to find something to eat or allow security personnel to walk me to my car. The times when automatic triggering might be hurtful to me and others is when fear keeps me from engaging with others or taking action that could potentially benefit us.

Automatic triggering can prevent us from having the very experiences that may help our brains make new connections and grow. In these circumstances, mental prescriptions are useful, providing reminders that others may feel as uncertain about us as we do about them. Knowing this, we can take the first step and introduce ourselves.

Mindfulness is a state in which we’re intentionally conscious or aware of something. Recent work tying together neuroplasticity and mindfulness helps us understand how mindfulness can enable us to subdue our automatic responses so that we can be more thoughtful and flexible in our responses to others.13

For us, this insight holds profound possibilities. When we’re intentionally mindful, we can seek to heighten our understanding of the beliefs and assumptions that drive people’s behavior. We can also use mindfulness to learn new approaches to effective communications and decision-making in multicultural workplaces.

When we’re intentionally mindful, we can seek to heighten our understanding of the beliefs and assumptions that drive people’s behavior. We can also use mindfulness to learn new approaches to effective communications and decision-making in multicultural workplaces.”

When we’re intentionally mindful, we can seek to heighten our understanding of the beliefs and assumptions that drive people’s behavior. We can also use mindfulness to learn new approaches to effective communications and decision-making in multicultural workplaces.”

With the use of brain-imaging studies, the effect of thought on the brain, known as self-directed neuroplasticity, demonstrates that different types of mindful meditation actually bring about anatomical changes in the brain. We all sometimes operate on “autopilot,” when we eat something or drive somewhere or undertake some task based on habit and without real awareness of what we’re doing. Mindfulness means not operating on autopilot. Instead, it requires that we pay attention purposefully and focus our attention on the present moment. When we’re mindful, we maintain conscious awareness of our thoughts, feelings, and actions in a nonjudgmental fashion. We awaken to experience each moment as it is, and we value that experience.14

The book Search Inside Yourself offers three steps that are intended to allow people to change themselves in exceptionally short timeframes (from one day to seven weeks). The author, Chade-Meng Tan, an engineer, offers a course on this multiple times a year at Google, providing participants with hands-on practice with these three steps: attention training, self-knowledge and self-mastery, and creating useful mental habits.15 Through the experiential course, people learn attention-focusing techniques to help bolster their creativity, reduce their stress, increase their empathy, and find ways to create greater meaning in their lives and jobs.

I think these same techniques could be leveraged for mindful meditation and reflection that would improve our brain neuroplasticity and help us become more compassionate to, and welcoming of, various types of persons.

By growing our self-awareness through mindfulness, we give ourselves permission to stop and consider our thoughts and feelings without judgment. The more we become aware, the easier it is to see where certain beliefs and actions might limit us. This self-compassion, which we all need in order to be able to look within ourselves and change those beliefs, also has the added benefit of expanding our humility toward others. We end up treating people different from us with greater kindness and caring.

As we grow and mature, our experience of the world expands. The beliefs and assumptions that we develop in our lives are typically based on general methods of information gathering. We do this through:

Interestingly, only one method, evidence-based believing, stems from our ability to use critical thinking. The skills we associate with evidence-based beliefs are skills that develop over time through education. In a courtroom, evidence may show that one thing causes another, and understanding this appeals to people. It feels logical and makes sense. In business, education, medicine, and many other fields, we typically look at events or outcomes that are measurable, scientifically studied, and tested with hypotheses.

But in actuality, the primordial power of our beliefs and assumptions comes far less from evidence. Family traditions and preferences strongly influence our religious practices, our political party preferences, and even our favorite sports teams. And society—through subtle and overt advertising, community groups, work teams, and our associates—also contributes to the informal information-gathering that profoundly affects what we believe and what we assume to be true.

What does it really mean to question assumptions in light of all this? It means that if we can apply evaluative thinking (also called critical thinking) to our life situations, it enables us to better consider varying points of view.

The Value in Questioning Assumptions

Throughout history, scientists have questioned the assumptions of others. Albert Einstein questioned Isaac Newton’s widely accepted laws of motion. If he hadn’t done this, he might not have gone on to develop his general theory of relativity.

On a more personal level, when my mother-in-law comes to visit, I never need to ask what time dinner should be served, because from her perspective, 5 p.m. is dinnertime. The assumption she makes is that people eat dinner at 5 p.m., and it does not occur to her to think about whether she is hungry at that time or not. She doesn’t question it because it seems natural and normal to her. The rest of my family is not likely to be hungry until later, so I find when I gently question her assumption, asking her if she’s actually even hungry at 5 p.m., she pauses to think, considers a varying viewpoint, and typically adjusts the behavior around her assumption. This helps resolve a small family issue around dinnertime; and although it serves as only a simplistic example, it makes the point that there’s often value in questioning assumptions.

In the workplace, assumptions that women are not as good as men when it comes to solving certain math or engineering problems can be a significant issue. Similarly, assumptions that whites have greater intellectual ability than Blacks, that younger people are more technically savvy than older people, or that men are better than women as CEOs of large companies (because they hold the majority of these positions) are assumptions worth questioning.

Beyond the workforce, there are also many more common stereotypes in parts of the world that are based on false assumptions. The idea that women are better than men at caring for children and elders, or that Blacks have more natural athletic ability than whites, are examples of assumptions that prove to be extremely limiting and problematic. As we surface our unconscious biases, questioning our beliefs about gender and family, Blacks and whites, and a host of other hidden preferences, we can empower ourselves to learn and grow by using evaluative thinking.

As we surface our unconscious biases, questioning our beliefs about gender and family, Blacks and whites, and a host of other hidden preferences, we can empower ourselves to learn and grow by using evaluative thinking.”

As we surface our unconscious biases, questioning our beliefs about gender and family, Blacks and whites, and a host of other hidden preferences, we can empower ourselves to learn and grow by using evaluative thinking.”

Think about something you strongly believe. Ask: “Is this belief true?” “Is this belief serving me?” “What would happen if I chose to believe something else?” Challenge yourself to investigate this belief by using trustworthy, scholarly, objective sources. Just because all your friends on social media think something is true, or you heard it on a news report, doesn’t mean it’s based on verifiable evidence.

If we begin to question things we believe and hear, our investigatory powers can lead us to much greater learning. But we need to be willing to be wrong, to empathically put ourselves in the place of others, and to adopt new mindsets and beliefs based on evidence, not hearsay or misplaced trust in advertising or social media.

We need to be willing to be wrong, to empathically put ourselves in the place of others, and to adopt new mindsets and beliefs based on evidence, not hearsay or misplaced trust.”

We need to be willing to be wrong, to empathically put ourselves in the place of others, and to adopt new mindsets and beliefs based on evidence, not hearsay or misplaced trust.”

Challenging Yourself

The unconscious belief that Blacks are inferior to whites is widespread, according to the data compiled from millions of people taking the Implicit Association Test. Yet, scientific evidence shows that there’s no biological difference between races. Race is a social construct. But how often are your actions guided by implicit beliefs?

Challenge yourself by going to implicit.harvard.edu/implicit/ to see what group you’re in: the 76% of people who unconsciously prefer white people over Black people, or the 24% who do not.

Anytime you question your assumptions and beliefs with a genuine desire to learn, you invite a level of discomfort. It takes openness, a willingness to be vulnerable, internal fortitude, and a lot of maturity. You’ll also need to be able to do it with nonattachment. Questions you could begin to ask yourself include:

Deciding What to Do about Bias

The human brain is hardwired to be cautious about differences of all sorts. Each one of us is uniquely different, so our human tendency to congregate with others based on shared gender, race, ethnicity, skills, abilities, and interests is natural. Unconscious biases are, quite simply, preferences we are unaware of. Inherent mechanisms in human brains enable situations to be simplified so that we can process them automatically and quickly.

Unconscious biases are simply

Unconscious biases are simply

preferences we are unaware of.”

If you are driving in traffic and a car suddenly veers in front of you, your brain acts without conscious thought and you step on the brake. Humans have evolved to be cautious about people, animals, things, and situations that are unfamiliar and, therefore, potentially unsafe. However, the same implicit assumptions may also lead us to make prejudicial judgments about people who are different from us.

My friend Katy Wright has been teaching incarcerated prisoners for nearly a decade. She loves her work and the opportunity to help people who have a desire to better themselves actually be able to do so. Her courses include prescribed curricula from the penal system, but she’s also taught communication skills to fathers behind bars so that they may maintain positive contact with their children while serving their terms.

Katy is limited in the kinds of questions she’s allowed to ask the men, yet their stories emerge nonetheless. As pictures of each prisoner’s upbringing, environment, and (frequently) horrific challenges they’ve faced emerge, along with the regrets they have and lessons they’ve learned, she develops a balanced empathy, a level of compassion, and an appreciation for each individual.

Not all of Katy’s friends and acquaintances value her work. Some judge her, questioning why she might choose to “waste” her time teaching people who’ve committed crimes when the need for teachers in school systems is so great. Katy recognizes that the prisoners she helps are the kind of people others often try to avoid contact with. But she says that in her experience, the men who come across as the most intimidating in a dangerous system are typically kind, caring people and, surprisingly, some of her best learners. Her story teaches us that conscious and unconscious bias prevents many of us outside the system from ever seeing or even being open to the potential that lies within other people.

Scientific data about unconscious bias, implicit associations, and neuroscience clearly shows that we’re all inherently biased. Like it or not, we are all somewhat racist, sexist, and a host of other unappealing labels. In fact, our biases typically run counter to what we believe to be true about ourselves. A stunning finding from the research on unconscious bias and implicit associations is that men are not the only ones biased against hiring and promoting women; women are often biased against other women; and Blacks can be biased against other Blacks.16 So automatic are these preferences that we need to constantly self-evaluate our behaviors.

Our biases typically run counter to what we believe to be true about ourselves.”

Our biases typically run counter to what we believe to be true about ourselves.”

Recognizing that our biases can be at odds with what we think about ourselves will be a major challenge when we begin to deal with our unconscious biases. In our questioning and evaluating, we’ll be confronted with the views we not only privately hold but also publicly state about the value and equality of people of all races, ethnicities, and other differences. It’s not easy for any of us to see ways in which our demonstrated, measurable behaviors can be at odds with what we believe.

We use membership in social groups to make automatic, unconscious judgments based on how similar or different we are from others. This explains why we tend to socialize with others from the same socioeconomic class, age group, and background. While this behavior is normal and natural, in business it serves an unintended consequence, because managers and leaders tend to hire, mentor, promote, and work with those like themselves. Diverse groups do not develop from these actions and behaviors; homogeneous groups do.

Substantial research validates that exposure to others is the single best way to remove bias and appreciate differences among people.17 Knowing this, and acknowledging my disdain for radical Islamists and my growing discomfort with seeing Muslims in my community, I challenged myself to visit the Islamic Cultural Center of Northern California. I shared my decision to visit the center with no one, and while driving to Oakland, where the center is based, I had two conversations going on in my head: I told myself I could just turn around and go home (the comfortable thing to do), or follow through with the visit (the uncomfortable thing to do). Not sure how it would go, I was hesitant to put myself out there, even though I knew it could be a positive first step.

I proceeded to the cultural center, and the visit was rewarding beyond measure. When I arrived, I was welcomed by a diverse, compassionate, caring group of Muslims. They shared artwork and literature to help me understand the kindness and value in their religion. The visit disarmed me. It affirmed my decision to welcome uncertainty and allow vulnerability. In facing my discomfort and bias and actually taking action, I opened myself up to be able to develop appreciation for others different from me. I was able to listen, to learn, and to grow.

The ramifications of change, based on this experience, have been positive for me in both attitude and behavior. Today, I’m more conscious of and intentional about expending the effort to welcome others in my community; I’m better able to act with compassion for people’s circumstances and feel gratitude that they’re here.

The next time you feel that someone different from you makes you uncomfortable simply because of that difference, consider taking a deep breath and recognizing this as a flag that you can react positively to. Work within your discomfort zone, acknowledge that the feeling you have is about you and not necessarily about them, and do the right thing. Give that person a chance to join your company, be promoted in your organization, take on a stretch assignment, and so on. Reflect. Be mindful. Use evaluative thinking skills.

Most reasonable people would agree that it’s neither fair nor smart to select a CEO just because he’s tall, or treat a patient with less compassion because she’s overweight, or hire a person named John versus Jane or Jamal if all three have the exact same credentials and experience. Yet data shows us that this occurs with regularity.18 Part of the reason is that our hidden biases enable these very occurrences.

If an inclusive leader does not want to limit human potential in an organization, this leader needs to work to recognize and counter the unconscious biases that drive these behaviors, and it must be a top organizational priority, not just for the recruiting staff, the people in human resources, or certain portions of the workforce. This must be a top priority for the chairman, the chief executive officer, all of his or her direct reports, all of their direct reports (Levels 1-2-3), and the board of directors, cascading down through the entire workforce. Taking one training class to learn about unconscious biases, while helpful, is grossly insufficient, because this is not a once-and-done undertaking.

Regular exposure to the Implicit Association Test (IAT) will help anyone who is interested in uncovering their hidden biases so that they can counter them. Most people who take the IAT (myself included) are unpleasantly surprised by evidence that shows their actions are out of sync with their professed beliefs and intentions. While we like to believe we’re progressively open-minded, fair, and without prejudice, it’s of course unsettling to find out that the opposite is often true. We can console ourselves with the knowledge that this does not mean, however, that we are bad or immoral people.

Oftentimes we are not aware of bias that is innate, hardwired, or unconscious. However, when we challenge ourselves to become aware of possible bias, then we must decide what to do about it. Once bias rises to a level of conscious awareness, we have the opportunity to overcome the bias, with practice, and thus to change our thinking, ourselves, and our environment.

There’s a big, looming question about whether company leaders and staff are willing to change their deeply rooted attitudes; and so feelings of shame, embarrassment, and disgust—both inside and outside the organization—may appear. Once we’re educated about an important topic that we know has potential negative effects, we must change our actions, assuming we have the desire and skills to do so.

When we challenge ourselves to become aware of possible bias, then we must decide what to do about it.”

When we challenge ourselves to become aware of possible bias, then we must decide what to do about it.”

Many companies, technology organizations in particular, insist they want a diverse and inclusive workforce. Yet data reveals that these companies are usually heavily male-oriented, mostly white, with some Asian and Indian employees; women, Blacks, Hispanics, and other minorities are severely underrepresented in these organizations. Exclusionary behaviors, resulting from unconscious negative biases, hidden beliefs, and even positive intentions that have negative unintended consequences, have led to the disparity in numbers.

To illustrate, let’s talk for a moment about the widespread, implicit belief that older people don’t understand technology as well as younger people. If teams that develop technology products in a company hold this implicit belief, or bias, they may likely refuse to solicit input from older people or value the suggestions of older people. This could prove to be a huge missed opportunity for a company to explore the thinking and ideas of a group with rich life experience, insights, and expertise to offer. And, given that the global population age sixty and over is projected to reach nearly 2 billion by 2050, this could mean the potential loss of a successful new product and services market.19

HOW BELIEFS AND ASSUMPTIONS RELATE TO DIVERSITY AND INCLUSION

Invisible dimensions of thought are assumptions, values, and beliefs.

Visible dimensions of thought manifest as behavior.

The cause-and-effect relationship is this: behavior is a direct result of what people assume, value, or believe. In other words, our thoughts are invisible to others and are based on what we value, believe, and assume; our actions are visible to others. So there’s a relationship here—how we act is a result of what we think.

Ask yourself:

We’ve all heard it said that America is the “land of opportunity.” Belief in the American Dream is about can-do individualism and goes something like this: anyone in this country can rise to a level of success based on his or her talents, abilities, and hard work. But children also inherit different starting points from the parents they were born to or raised by. Children from poor families have to work much harder to benefit from the privileges afforded the middle and upper classes. Social class, immigration status, and discrimination (conscious and unconscious) are factors that impede a fair and equal system of opportunity for all. And, of course, inherited wealth says nothing about the talent, ability, or hard work of the person inheriting the benefits.

Most companies want us to believe that they hire and promote the most-qualified applicants, regardless of gender, race, age, or other differences. Technology companies and select others claim that their overwhelmingly young, white male-dominated workforces simply reflect the larger problem of insufficient numbers of older people, Blacks, Latinos, or women available with the skills necessary to do the job. The sentiment is “We’d hire them, but they’re just not there.”

More recently, the tech industry has begun to acknowledge ways in which unconscious biases get in the way of hiring others who are not like people already in the industry. Even when the most-qualified applicants for a position are women or people from underrepresented minorities, the reality is that company leaders tend to still hire based on who they feel the most comfortable with—applicants they can relate to or who they think would be a good “fit” in the organization’s culture.

For an industry that prides itself on daring innovation, the situation demonstrates stagnant, backward thinking that, even if inadvertent, is designed to minimize diverse hires. Tech companies seem to want and favor underrepresented minorities who grew up in affluence, attended top-tier universities, and possess myriad connections to leverage—elitists, like them.

Debby Irving, in her book Waking Up White, and Finding Myself in the Story of Race,20 shares her feelings about discovering that the GI Bill, instituted at the end of WWII to help returning service people obtain higher education and secure home loans, was, through its implementation, effectively for whites only. At the time, a quota system limiting the number of Black students in colleges and universities restricted the number of eligible Blacks who could attend. Yet a preponderance of returning GIs, about one million, in fact, were Black.

At the same time, the Federal Housing Administration (FHA) hindered opportunities for non-whites to purchase homes by instituting policies suggesting that the skin color of a homeowner could affect the value of a given home in a neighborhood. This perpetuated a common belief that if Black people, or other non-whites, moved into white neighborhoods, housing values would decline. Specifically, the FHA gave builders loans through banks, on the condition that no Blacks could be sold homes in subdivisions. Also, no suburban homebuyer could resell to a Black person; and should this occur, the white neighbor could both evict the Black homeowner and be entitled under the law to collect damages. These were known as housing and neighborhood covenants.

Eventually, these practices were ruled illegal, and the Fair Housing Act contained in Civil Rights legislation during the late 1960s changed the law to remove discriminatory housing practices. But by then, the damage was done. As a result of public policy, inner-city public housing became all Black, while suburbs became all white. Whites got equity appreciation from their housing, while Blacks did not, the effects of which continue to this day.21 The bottom line is that many whites gained education and housing benefits during this time in history, but fewer than 5% of Blacks did.22 The “American Dream” was rigged by a system of discrimination.

Many Americans acknowledge historical forms of discrimination, including mass killings of Native Americans and the displacement of the remaining Native Americans to reservations; Africans brought to America and sold at auction as slaves; Jim Crow legislation; and the internment of Japanese-Americans during WWII. Whites, the primary beneficiaries of opportunities during these times, can be labeled the “in-group.” All others were considered the “out-groups.” When we act as though the small number of women and minorities in technology and other industries is due to individual failings or lack of availability in the market, we elevate the idea of meritocracy and ignore the effects of hidden bias, subtle prejudice, and systemic discrimination.

When we act as though the small number of women and minorities in technology and other industries is due to individual failings or lack of availability in the market, we elevate the idea of meritocracy and ignore the effects of hidden bias, subtle prejudice, and systemic discrimination.”

When we act as though the small number of women and minorities in technology and other industries is due to individual failings or lack of availability in the market, we elevate the idea of meritocracy and ignore the effects of hidden bias, subtle prejudice, and systemic discrimination.”

Laws have changed since the end of WWII, but to what extent have beliefs and behaviors changed? Do employment and promotional opportunities exist equally today in companies? Clearly not. Unconscious bias alone prevents that. The top jobs go primarily to white men, role models for women and minorities are few, and opportunities for people who are a part of the “outgroup” occur at an astoundingly slow pace.

Leave-of-absence policies, designed mainly for women with childcare and eldercare responsibilities, and performance evaluation systems that say more about the person giving the assessment than the individual receiving it, perpetuate discrimination under the guise of “helpfulness” or “merit.”23 We need to ask some tough questions about whom our systems and policies are really helping—and whom they leave out.

Perspective

Imagine a black person and a white person in a race together. The white person has a jet pack, and the black person does not. Both people run like that for a little while; then someone says that this isn’t fair. So, the white person has the jet pack taken away. But the race doesn’t start over; it just continues from where the runners were. A few minutes later, someone says that this still isn’t fair, because although no one has a jet pack now, the white runner has already benefited from its earlier use. Since the race can’t be started over, this person suggests giving the black person the jet pack for a little while.

In response to this, someone else asks, “But isn’t it racist to give the jet pack to a runner, based on race?”24

This story illustrates the structural institution we’re all born into and suggests that we’re all complicit in perpetuating a system of bias. “Restarting the race” for blacks, Latinos, Native Americans, women, people with disabilities, individuals with non-heterosexual orientation, or those with other differences are not options.

Interventions, however widely implemented, can serve to advance diversity in organizations. When some equally qualified candidates are competing for a job and the role is given to the underrepresented minority, this may be selection bias—but it is justified selection bias. The company wants and needs a diverse workforce, and the candidate deserves to “wear the jet pack” for a time.

Those leaders and teams progressive enough in their thinking to take this approach need to prepare for the inevitable backlash that will arise. The myth of meritocracy holds that the women and minorities selected with intention got their role only because of their minority status. This implication assumes that the person is not as qualified or credentialed as the individual who was not selected.

It’s imperative for leaders to openly address that their decision to employ selection bias is from among equally qualified candidates. It takes courage and forward thinking to act on these important choices. And individuals, groups, organizations, and society benefit from this selection.

The myth of meritocracy is used inside and outside many sectors to justify the lack of diversity. It’s essentially like telling women and underrepresented minorities that they only have themselves to blame if they didn’t get the job or the promotion. And when women and people of color exit the workforce with much greater frequency than white, Asian, and Indian men, the self-serving belief in meritocracy lessens the need to address the issue and examine why this even happens.

Dismantling the myth of meritocracy makes us all accountable for racism, sexism, classism, elitism, and all the other isms we’ve perpetuated on one another. Those companies who ground themselves in truth, data, introspection, and reality—for instance, companies scoring high in the global DiversityInc Top 50 annual survey—are excellent examples of how to do the work of diversity and inclusion and succeed. Other organizations would do well to learn from them.

A Success Story

Sodexo, the 19th-largest employer in the world, with over fifty years of success, has 420,000 employees, comprising more than 100 different cultural backgrounds. Operating in eighty countries, Sodexo is the global leader in quality-of-life services, which support the well-being of people in their daily living, including in workplaces, schools, and healthcare settings. Its stellar work focuses on improvements to the environment, community health, and socioeconomic opportunity, all factors that affect the overall quality of human life.

What does this impressive company say is the reason for its success? According to Sodexo’s 2016 employee survey, diversity and inclusion (D&I) is one of the top two drivers of worker engagement. Its 2016 Global Diversity and Inclusion Report details a decades-long actionable commitment to diversity and inclusion as a business strategy that produces a significant global competitive advantage. Sodexo challenges itself with programs to hold all employees accountable to its diversity commitments. Its research shows that Sodexo teams made up of 40 to 60% female managers, called gender-balanced teams, have measurably higher performance than unbalanced teams. Specifically, these teams have greater engagement, higher brand awareness, better client retention, and increased profit and growth over three consecutive years.

Changing the way we think about companies by looking at how employee belief systems and values affect an organization holds exciting possibilities for the future. As inclusive leaders and their followers apply a framework to think about differences among people and use critical thinking to guide them, better decisions are made that benefit everyone. Unconscious biases exist in all people, but they’re malleable—this is important to remember. The opportunity to make the unconscious conscious, be mindful, and apply evaluative thinking is hard work. But this hard work positions us to fix the myth of meritocracy and create organizations that thrive with brilliance and performance.

Here are some key points to remember from this chapter:

Need to know how to apply what you just read? Here are some steps and ideas:

•Reframing the way you think through practice, awareness, and intention leads to new possibilities to achieve success in workforce diversity and ultimately the success of the company. To begin to do this, reflect on these questions:

•Why do I believe what I believe?

•How do I know what I know?

•What would need to change for me to hold a completely different viewpoint?

•Ask yourself: “How are diversity and inclusion affected by the values, beliefs, and assumptions of my company founders?” Understanding the real company culture requires answering this question.

•Acknowledge and understand the framework for thinking about differences (pp. 61) and how your life has been affected by it.

•Just as you know your strengths and personality type, learn your unconscious biases, so that your awareness can help counter them for more effective decision-making. As you do this, practice mindfulness. One way to get started is to take the Implicit Association Test (IAT) at implicit.harvard.edu/implicit/takeatest.html. Learn your biases and actively work to counter them. Then, retake the IAT six months later to see how you have changed!

•Diversity begins at the end of your comfort zone. Lean into discomfort. Start to see this feeling like a positive, even essential, thing as you learn how to navigate differences among people.

•Practice the use of critical (evaluative) thinking skills. Write mental prescriptions to shift your thinking about those who are different from you.

•Ask yourself whether your actions work to support or dismantle “in-groups.” Do your behaviors include or exclude others? What will you do to change this?

•Become a cultural detective. Work every day to develop curiosity about difference. You can do this by visiting your local cultural centers to learn about other cultures and people. You can also do this simply by asking questions. Always be in learning mode.