Some scholars have argued that it is not possible, or worthwhile, to attempt to compile a collective terminology of Norse sorcery. In her recent survey of the field, for example, Catharina Raudvere has suggested that,

… there is no need to establish a taxonomic structure that does not exist in the sources. Precise classifications are impossible to formulate since the texts give contradictory statements – not because the Norsemen had confused opinions, but because the concepts of trolldómr and related ideas were used for explanations in so many very different areas of life.

Raudvere 2001: 80

This is correct to the extent that this plurality of contextual meanings was certainly a part of the seiðr complex, but this should not be used to argue that we cannot distinguish between different types of practice and practitioner. The analysis in the preceding pages has attempted to demonstrate this, and while each of these people and the rituals they performed are different, they also fall into patterns – some broad, some more clearly defined.

Gathering together the categories discussed above, I would argue that in fact we can begin to arrive at a basic terminology for the performers of Nordic sorcery in the Viking Age. The chronology and contemporaneity of the terms is problematic, of course, but this serves as an outline on which to build. In particular, we can compare it with a similar array of terms among the Sámi that we shall examine in the next chapter.

The generic term ‘sorcerer’ has been used in the translations for any word that clearly refers to someone who works magic, but without any more precise association. Obviously the different ‘sorcerer’ words had their own meanings, now lost to us, but we should also remember that they may also have been generics in the medieval period. It must be emphasised that in the later texts terms are often employed with an arbitrary meaning, as with ‘wizard’, ‘sorcerer’, ‘magician’ and similar words today. This is especially true of terms based on galdr- and spá-.

The word maðr can grammatically refer to individuals of both sexes, but as noted above the only instance of its use for a magic-using woman is when Kotkell’s family of three male sorcerers and one sorceress are collectively described as seiðmenn. This is therefore included here among the male terms.

Male (including -maðr formations):

•seiðmaðr ‘seiðr-man’

•seiðskratti ‘evil-seiðr-sorcerer’?

•seiðberendr ‘seiðr-carrier’? (obscene?)

•spámaðr ‘prophecy-man’

•falsspámaðr ‘false prophecy-man’

•villuspámaðr ‘false prophecy-man’

•galdramaðr ‘galdr-man’

•galdrakarl ‘galdr-man’

•galdrasmiðr ‘galdr-smith’

•galdraraumr ‘great-galdr-man’

•galdrameistari ‘galdr-master’

•galdradrengr ‘galdr-attendant’?

•vitki sorcerer

•fjolkyngismaðr sorcerer

•fjolkyngisberendr ‘sorcery-bearer’

•gandrekr ‘gandr-man’, ‘gandr-warrior’

•kunáttumaðr ‘man who knows magic’

•vísendamaðr ‘man who knows’

•tauframaðr ‘charm-man’

•gerningamaðr sorcerer

Female:

•volva ‘staff-bearer’, seeress, sibyl?

•seiðkona ‘seiðr-woman’

•spákona ‘prophecy-woman’

•spákerling ‘old prophecy-woman’

•kveldriða ‘evening-rider’

•trollriða ‘rider of witchcraft’

•myrkriða ‘darkness-rider’ or ‘night-rider’

•munnriða ‘mouth-rider’

•túnriða ‘fence-rider’ or ‘roof-rider’

•kaldriða ‘cold-rider’ • þráðriða ‘thread-rider’

•galdrakona ‘galdr-woman’

•galdrakerling ‘old-galdr-woman’

•galdrasnót ‘galdr-lady’

•galdrakind ‘galdr-creature’? (i.e. sorceress, negative?)

•vitka* sorceress

•fjolkyngiskona sorceress

•vísendakona ‘wise woman’, ‘woman who knows’

•heiðr sorceress (positive?)

•fordæða evil witch?

•flagð(kona) evil witch?

•fála witch? (negative)

•gýgr witch? (negative)

•hála witch? (negative)

•skass witch? (negative)

We have examined these people in the written sources, their possible affiliations and relative context, but what evidence do we have for them from the funerary material?

The archaeological material that directly relates to seiðr and its performers can be divided into two broad categories:

•individual objects that may be interpreted either as tools for the working of sorcery or as otherwise connected with its practice

•the graves of possible sorcerers

The latter category can be defined as such due to the presence of the former, and by evidence of unusual mortuary behaviour, but the material culture of Nordic sorcery is also found in archaeological contexts unassociated with graves. Each type of object will be considered separately in the next section on the practicalities of seiðr performances, but we can first examine the burials as complete assemblages.

Very many burials from Viking-Age Scandinavia contain objects associated with spiritual belief in some way, most typically ‘amulets’ of various kinds such as Þórr’s hammers, miniature sickles and so on. There is little to suggest that these artefacts were directly associated with magic, though some of them may have symbolised aspects of its practice (two categories of these, miniature chairs and model staffs, are considered below). In interpreting a grave as that of a ‘sorcerer’, we must therefore seek to locate objects that were actually employed in performance. Of these, the two most characteristic are probably staffs and narcotics.

In total there are 26 Viking-Age burials known from Norway, Sweden and Denmark which contain iron staffs of a kind that may arguably be related to the practice of sorcery, following the specific interpretations set out later in this chapter. 12 staffs are known from stray finds across the same region, and one more has been excavated from a cultic deposition. Outside Scandinavia proper, but within the Viking world and the Norse sphere of influence and colonisation, another 8 iron staffs have been recovered from burials. In addition to these 47 iron staffs from various contexts, 4 wooden staffs are also known from Scandinavia – 3 from burials and one ritually deposited in a bog – making a total of some 51 staffs of all kinds known from the Viking world.

The staff graves present a number of empirical problems. Firstly, as we shall see below the total corpus of staffs includes different types, some of which are more secure than others in their association with seiðr; they range from clear examples to others which are simply iron rods, but buried in contexts that imply a function beyond the ordinary. Secondly, many of the burials in which these objects are found are either poorly preserved, badly recorded, or else in cremation deposits that provide little information as to the deceased. If we are to attempt an ‘archaeology of sorcerers’, rather than merely their equipment, we therefore need to find burials which combine appropriate artefactual assemblages with acceptable levels of preservation.

Following these criteria, we find that there are ten Scandinavian Viking-Age graves which can be reasonably claimed to be those of volur or similar practitioners of sorcery, and which are also relatively intact and well-recorded. These include seven inhumations and three cremations. To these we may add an inhumation from the Isle of Man which also fulfils these criteria.

We can begin with four graves from the cemeteries around the Viking-Age town of Birka, in Lake Mälaren (Fig. 3.3), three of which have also been reviewed in dramatic form by Anna Lihammer (2012: 197–204) in her study of ruler figures.

Bj. 760 is a small cremation under a mound in the southwestern corner of the Hemlanden cemetery, immediately east of the rampart. It is largely unremarkable, with finds consisting solely of two beads, fragments of iron nails presumably from some wooden object, and a small ceramic vessel which probably served to contain the cremated bones (Gardeła 2016: 329); what sets it apart is the presence of one of the best-preserved iron staffs from any Viking-Age funerary context. Unlike the other objects, the staff has no details of its location in the grave, which seems unusual given its spectacular nature and the stark contrast that it makes with the other grave goods. Significantly perhaps, the staff does not seem to have been burnt. Arbman speculates that it may have been laid in the fill of the mound above the level of the cremation deposit (1943: 278), which would suggest that the act of placing the staff played some other role in the burial ritual than in Bj. 834 and 845 (see below).

The first edition of this book followed Arbman’s suggestion (1943: 278) that the iron staff labelled by Stolpe as coming from Bj. 760 in fact derived from Bj. 660, which seemed to be supported by the close match between the excavator’s object description and the field drawings of the latter grave. Furthermore, alone among the finds from Bj. 660, the staff clearly shown on the excavation plans could not be found when Arbman was preparing the publication of the graves; this seemed to me good evidence that the staff labelled as deriving from Bj. 760 was actually the ‘missing’ artefact from Bj. 660. This re-allocation of the find had also been supported by Kyhlberg (1980b: 274) and Arwidsson (1986: 165). However, this situation changed in the years following the publication of my book, in the course of Leszek Gardeła’s research for his 2012 PhD thesis. Bearing in mind that the extant find was unambiguously labelled as coming from Bj. 760, with the assistance of Swedish History Museum curator Gunnar Andersson, Gardeła decided to try to locate the documented Bj. 660 staff in the finds magazines in Stockholm – and succeeded (Gardeła 2016: 57ff). Contrary to the position taken in the first edition, there is now no doubt that both Bj. 660 and Bj. 760 contained staffs, bringing the total currently known from the island’s cemeteries to four (together with Bj. 834 and Bj. 845 below).

Fig. 3.3 Plan of Viking Age Birka, showing the urban settlement and the surrounding cemeteries. The location of the four possible ‘sorceress graves’ is shown: 1. Bj. 660, 2. Bj. 760, 3. Bj. 834, 4. Bj. 845 (map prepared by Charlotte Hedenstierna-Jonson).

Little more can be said about Bj. 760 given the meagre nature of the records, but it is an important addition to the Birka corpus, and also demonstrates that such objects were not only buried with high-status chamber inhumations. In this, as we shall see below, the Birka graves now collectively look less distinctive from the other forms of staff burials than they first appeared.

Bj. 660 is a large chamber grave containing a probable female inhumation, which Arbman places at an unknown location within the cemetery north of the hillfort (1943: 231ff). Working from Stolpe’s excavation diaries, Ola Kyhlberg has achieved a more precise location, and suggests that all the graves in the sequence Bj. 656–660 can be placed within a small area on the northern periphery of cemetery 2A, at the very edge of the town and at the foot of the slope up towards the hillfort (pers. comm.; see Fig. 3.3).

Oriented northwest–southeast and measuring 2.45×1.5m, the grave-cut was 1.8 m deep. The chamber does not seem to have had wooden walls, though in each corner the excavators found what appeared to be a single filled-in post-hole. These perhaps related to the construction of the grave, but they may equally be the remains of some ritual about which we know nothing. Stolpe does not record in his notebooks whether or not he emptied the ‘post-holes’.

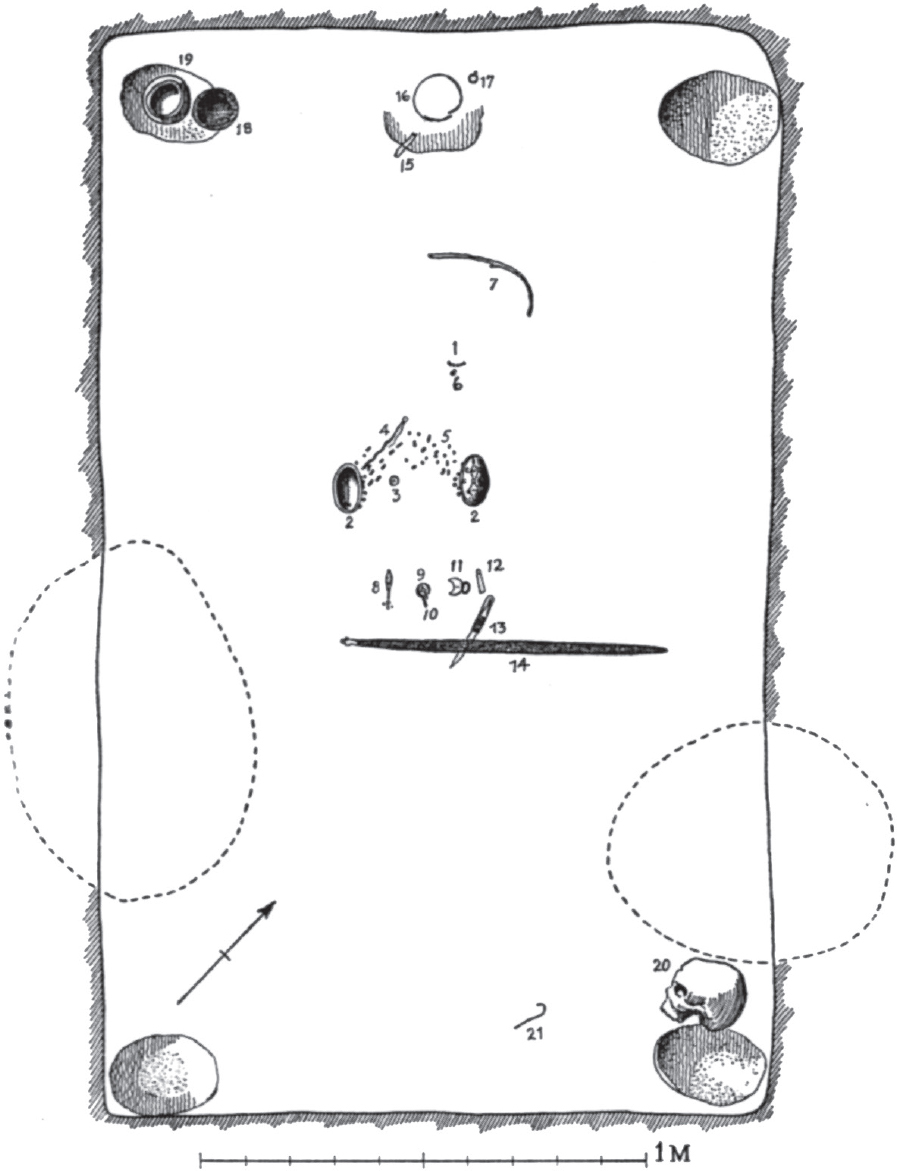

Fig. 3.4 Plan of Birka chamber-grave Bj. 660 (field drawing by Hjalmar Stolpe, ATA Stockholm, in the public domain).

In my discussion of the chamber below, reference is made to the numbered finds on the plan of the grave, and to the reconstruction drawing commissioned for this book (Figs 3.4–3.6). The objects numbered 20 and 21 on the plan are later intrusions into the fill, and are unrelated to the original grave. The large dotted shapes at the sides of the burial are boulders which originally lay outside the edges of the grave, but which subsided into it at a later date as the earth settled. Again, they are unrelated to the burial itself.

Of the skeleton only the teeth remained (1), and all sex determinations in this burial are thus made through artefactual associations alone. For the rest of this book, the occupants of this and other similar graves will be referred to with female pronouns, but see chapter 8 below for the considerable uncertainities surrounding such vocabularies and the attitudes behind them; this ambiguity should be borne in mind throughout the discussion that follows.

From the positions of the grave-goods, the woman (if such this person was) seems to have been lying full-length on her back in the centre of the chamber. She was wearing a silver-threaded silk band (7) around her head, as in grave Bj. 845 below. The woman was otherwise dressed in ‘conventional’ Viking-Age female costume, with at least one garment (a silk shawl?) edged with a narrow band of silver work as in grave Bj. 834. She was wearing a pair of oval brooches of type P51 C2, worn in the usual way (2), with a thin silver chain (4) perhaps strung on the right-hand of the two. A necklace of 28 beads (5) was strung between the oval brooches, including examples of rock crystal, glass with gold and silverfoil, and polychromatic glass with patterns. At the centre of the strings of beads was a circular pendant with a whirling design (3).

Fig. 3.5 Plan of Birka chamber-grave Bj. 660 (drawing by Harald Olsson after Arbman 1943: 232).

Under the oval brooch on her right breast was one of the most famous of all the Birka grave finds, namely the silver granulated crucifix which appears in every discussion of the material culture of early Scandinavian Christianity. It had presumably been strung with the beads, or perhaps attached to the silver chain.

As the body had decayed, or possibly while the woman was placed in the grave, the arrangement of jewellery had been disturbed. All the bead necklaces had slid towards the woman’s head, and the right-hand oval brooch had fallen to the side. None of this is remarkable, except for the difficulty it makes for interpreting another piece of jewellery – a clear glass bead strung on a ring of gold wire (6), which was found by the woman’s teeth. It is possible that it had rolled there from the main set of necklaces, but it is hard to see why this object alone should have moved in this way. All the usual forms of taphonomic process would surely have disturbed other beads from such a fragile context. Another possibility is that this bead represented a form of facial jewellery, a piercing of some kind, most likely either in the lip or the nose. In the reconstruction drawing we have chosen to depict the latter. An outside possibility is that it had for some reason been placed in the woman’s mouth.

Fig. 3.6 Reconstruction of Birka chamber-grave Bj. 660 as it may have appeared when the burial was sealed (drawing by Þórhallur Þráinsson).

Attached to her belt she wore a number of small objects. From her right to left, these included a bronze ear-spoon (8) with a silver bead strung on it, a pair of iron scissors (9), an iron awl with a perforated handle (10), a curved pendant of Eastern origin (11), a whetstone of banded slate (12) and an iron knife (13).

Lying at right angles across the woman’s body just below the waist, with the ‘handle’ end to the southwest (perhaps in the woman’s hand?) was an iron staff (14). In a brief note, Stolpe described it as, “an iron object…with a bronze knob at one end”.

At the centre top of the grave, above the woman’s head, was a wooden box with iron mounts (15 & 17). Resting on this was a conical glass beaker of Continental type (16). In the western corner of the grave, resting on the filled-in hole, was a small ceramic vessel (19), next to which was a small iron-clad vessel (18). This perhaps supports the idea that the holes were more than constructional features. At the lower centre of the south-western long wall, up against the side of the chamber and under the stone shown as a dotted line, was a large wooden bucket (not shown on the plan – see the reconstruction).

The woman in Bj. 660 was buried with rich grave-goods, including imports such as the glass, and she was clearly a person of some standing in the community. The placement of the staff also emphasises its importance to the woman, laid as if for immediate use. In addition, the presence of the silver crucifix may also be interpreted in the context of a reference to the supernatural. In this context, the presence of the cross would make sense simply as an object of spiritual power, and the fact of its symbolism in a different faith would not contradict its use in a non-Christian ritual context – indeed, this might have been the very point (Andersson 2018: 110– 15). An interesting parallel has been discovered in Denmark from a female grave at Ketting in Als, southern Jylland, where an almost identical crucifix occurs in a wagon burial bearing remarkable similarities with grave 4 from Fyrkat, discussed below (Eisenschmidt 2013); a gold example, again identical to that from Bj.660 apart from the use of more precious metal, has also been found at Aunslev in Denmark (Beck 2016). It has been siuggested that both the Als and Aunslev examples are so close in detail to the crucifix from Bj.660 that they were certainly made in the same workshop, and probably by the same person (ibid: 16) – an interesting extra dimension to the life of the woman in the Birka grave.

With a degree of caution, grave Bj. 660 was assigned to the very end of the ninth century by Arwidsson (1986: 166), which with a margin extending into the early 900s is also supported by Kyhlberg’s chronology for the cemetery on the basis of clustered coin datings (1980a: 82; 1980b: 274). However, a more precise – and slightly later – date can probably be achieved with reference to the oval brooches. In his comprehensive study of these objects, Ingmar Jansson notes that brooches of this type occur in the very richest graves (1985: 133), and suggests that they are most common in phase three of his Middle Viking Period (ibid: 174f; 1991: 268f). This period begins sometime in the early tenth century, which provides our most secure date for grave Bj. 660.

Burial Bj. 834 at Birka was a double inhumation located in sector 1C of the Hemlanden cemetery. Here a man and woman had been interred together in a chamber grave, aligned east–west and located beneath – and thus predating – the town rampart (Arbman 1940: 304–8).

As above, reference is made to the numbered finds on the plan of the grave (Figs 3.7, 3.8), and to the reconstruction drawing. My observations about the disposition of the burial in Bj. 834 are based on an examination of Stolpe’s original field drawings, in the form of the photographic enlargements made in the late 1970s for Uppsala University when the Birka cemetery publications were being prepared. These primary records show more detail than the plans redrawn for Arbman’s report from 1940–41, which in some cases also include errors in the copying. All of Stolpe’s field records for his Birka cemetery excavations are now also available online at the Birkaportalen of the Swedish History Museum (http://historiska.se/birka/).

The chamber was very substantial, 4 m long by 2 m wide, and 1.95 m deep – almost an underground room. The floor was bare earth but the walls were lined with horizontally-laid timber planks up to almost the lip of the grave cut. There were no corner posts, as the planks of the long walls simply butted against the end walls and held them in place. The grave was divided into two sections, a main burial chamber 2.6 × 2 m, and a raised platform at the east end, 1.4 m deep and 0.3 m high. The platform was built up of large, flat stones held in place by the wooden walls of the grave and a revetment of horizontal planks along its western edge, facing the main burial chamber.

Lying on the platform were two draught horses, their legs folded and their heads to the south. After they had been killed, the horses had been carefully arranged in the grave with their necks curled round so that the heads rested on the forelegs. It is possible that the animals had been decapitated, which would account for the strange position of their heads, but there is no direct indication of this on the plan or the bones. The horse to the west was 7–8 years old, while the horse to the east was 4–4½ years. The horses were buried wearing costly bridles and draught harness of good quality, with ornamental rings, tackle and strap-distributors, decorated with mounts. The western horse was shod with four crampons (25, 26), implying a winter burial, and seems to have had a single glass bead hanging from its bridle (28). Lying over the horses was a whip mounted with rattles (36).

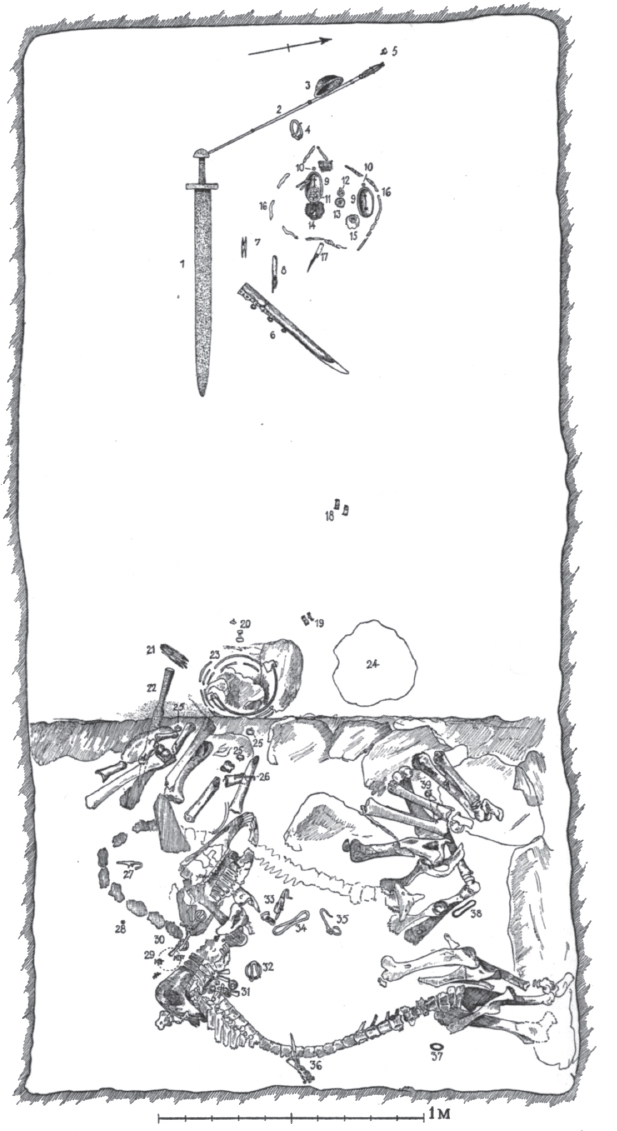

Fig. 3.7 Plan of the double inhumation in Birka chamber-grave Bj. 834 (field drawing by Hjalmar Stolpe, ATA Stockholm, in the public domain).

The arrangement of the main grave was highly complex, and requires some discussion before moving on to the grave-goods. The primary problem in understanding how the bodies were placed in the grave is that the skeletons have not survived beyond a single set of teeth. The two sets of shoes, double sets of jewellery and other conventionally ‘sexed’ objects, strongly suggest that there were two bodies in the grave, assumed to be a man and a woman (though with caveats as for Bj. 660 above). Double burials of this kind are not uncommon at Birka, and are known from skeletal remains which survive in other graves.

Fig. 3.8 Plan of the double inhumation in Birka chamber-grave Bj. 834 (drawing by Harald Olsson after Arbman 1943: 306).

Kyhlberg argues that the woman’s burial in Bj. 834 is secondary (1980b: 274), having been added to what was originally a chamber built for a man. However, in all the other Birka chamber-graves where secondary burials can be proven to have occurred soon enough after the first burial that soil had not accumulated between them, not only has the primary skeleton been pushed to one side (we cannot know this about Bj. 834 because the woman’s teeth are the only surviving human bones) but so have the grave goods associated with it (Gräslund 1980: 36f; cf. Bj. 703 and 823). In Bj. 834 by contrast the man’s equipment is still in situ. In short there is no reason to suppose that Bj. 834 was not a simultaneous double burial.

Our main parallel for the disposition of Bj. 834 comes from another Birka chamber grave, Bj. 644, in which enough bone fortunately survives to make a more detailed interpretation possible. This is especially important, because it seems that Bj. 644 contained the body of a man seated on a chair, with the body of a woman placed on top of him in the same position (i.e. two people in the same chair, their bodies ‘stacked’ in a conventional sitting posture, rather than the woman sitting cross-wise on the man’s lap; Fig. 3.9). The evidence for this is three-fold:

Fig. 3.9 Plan of Birka chamber-grave Bj. 644, used to determine the original disposition of grave Bj. 834. Both burials seem to have contained a man seated in a chair, with a woman seated on top of him in his lap (after Arbman 1943: 222).

•both femurs of both bodies were preserved, and were lying exactly adjacent to one another – i.e. the legs of the dead were exactly parallel, and the bodies were on top of one another

•in itself this could mean that they were buried in an extended position one above the other, but the position of the man’s skull rules this out: the only situation that could produce this relative location of the bones is that the dead were seated

•the woman’s jewellery was found in appropriate positions to indicate that it was worn on the body, but the complete set of brooches was inverted, i.e. when found the woman was lying face-down; again, this would result if she had been uppermost in the chair and had fallen out of it to one side.

The bodies and the chair had all decayed, naturally, and the different rates at which this took place would explain the final positions in which the different parts of the corpses came to rest. In his annotations on the original excavation plan of this grave, Stolpe writes that the bodies in Bj. 644 must have been seated. He does not specify a single chair (the Swedish is ambiguous), but the superimposition of the thigh-bones could not come about if the dead had been seated separately. The idea of two bodies sitting on the same chair was put forward explicitly by Arbman (1943: 221), and supported by Gräslund (1980: 37). I find no reason to disagree, as this interpretation is really the only one that fits the combination of skeletal evidence and the positions of the grave-goods.

In Bj. 834 it is difficult to see how the bodies could have been placed if buried extended on their backs, as the grave-goods leave no room for them to have been laid out side by side. What evidence is there then to indicate that they may have been seated? Here we lack the bones that made such a specific interpretation possible in Bj. 644, but the relative positions of the grave goods are the same – especially the sword and the woman’s jewellery. A close examination of the field drawings clearly shows that the oval brooches are upside down, but still in the correct locations to be attached to the body’s clothing when they fell into this position. In itself this could mean that the woman was buried prone, but here we can refer back to Bj. 644. Again, such a position for the body would be expected if the woman was in fact originally seated, and at some point in the decay process slumped over to one side and then finally out of the chair (Kyhlberg agrees with this, but as a secondary burial – 1980b: 275). I have discussed this with a former police officer, who confirmed that in cases where people have died sitting in a chair and their bodies have not been found for some time, the corpse is often discovered face-down on the floor in precisely this way.

The grave-goods provide an answer to the obvious question as to how two bodies would have stayed on the chair in the first place if placed in this way. On the plan we can note object 16 which was a thin chain of iron sections linked by loops, found spread out on the floor of the grave enclosing the woman’s jewellery in a rough oval. This could have been used to hold the bodies on the chair, fastened under their arms, and then fallen with them as they (or the chair) decayed. By the time this happened the bodies would have been essentially skeletonised, but perhaps still held together by their clothing. All of this would fit with the positions of the objects in the grave. Thus in Bj. 834 it seems that in approximately the centre of the chamber stood a chair, facing east, on which was sitting a man with a woman on top of him (Figs 3.10, 3.11).

Fig. 3.10 Reconstruction of the double inhumation in Birka chamber-grave Bj. 834 as it may have appeared when the burial was sealed, seen from above (drawing by Þórhallur Þráinsson).

Fig. 3.11 Reconstruction of the double inhumation in Birka chamber-grave Bj. 834 as it may have appeared when the burial was sealed, seen from the side (drawing by Þórhallur Þráinsson).

The idea that the dead were sometimes seated in the chamber-graves is also found in several literary sources, and is supported by at least two sagas. The most vivid account, and the most archaeologically useful, comes from Grettis saga Ásmundarsonar 18. The anti-hero Grettir has decided to rob a large burial mound on a headland, over which he has seen flames hovering at night (the idea of burial fires is found in other sources too, notably the un-named poem usually known in English as ‘The Waking of Angantyr’ and found in Hervarar saga ok Heiðreks konungs; here, as in Grettis saga, the fires are taken to denote the presence of treasure in the mound beneath). Grettir is told that the mound contains the remains of the former landowner of the region, who has since haunted the area so as to make it uninhabitable by any save his own descendants. Undeterred, and assisted by the local farmer Auðunn, he begins to break into the mound from the top. He works hard until he reaches the ‘rafters’ (viðir), which he then breaks through. Lowering a rope, he prepares to enter the barrow:

Gekk Grettir þá í hauginn; var þar myrkt ok þeygi þefgott. Leitask hann nú fyrir, hversu háttat var. Hann fann hestbein, ok síðan drap hann sér við stólbrúðir ok fann, at þar sat maðr á stóli. Þar var fé mikit í gulli ok silfri borit saman ok einn kistill settr undir fœtr honum, fullr af silfri. Grettir tók þetta fé allt ok bar til festar; ok er hann gekk útar eptir hauginum, var gripit til hans fast. Lét hann þá laust féit, en rézk í mót þeim, ok tókusk þeir þá til heldr óþyrmiliga. Gekk nú upp allt þat, er fyrir varð; sótti haugbúinn með kappi. Grettir fór undan lengi, ok þar kemr, at han sér, at eigi mun dugua at hlífask við. Sparir nú hvárrgi annan; fœrask þeir þangat, er hestbeinin váru; kippðusk þeir þar um lengi, ok fóru ýmsir á kné, en svá lauk, at haugbúinn fell á bak aptr, ok varð af því dykr mikill.

Then Grettir went into the mound. Inside it was dark, and the air not very sweet. He groped about to find out how things were arranged. He came upon some horse bones, then he knocked against the carved backpost of a chair, and he could feel someone sitting in it. A great treasure of gold and silver was gathered there, and under the man’s feet was a chest full of silver. Grettir took all the treasure and carried it towards the rope, but as he was making his way through the barrow he was seized fast by someone. He let go of the treasure and turned to attack, and they set on each other mercilessly, so that everything in their way was thrown out of place. The mound-dweller attacked vigorously, and for a while Grettir had to give way, but finally he realised that this was not a good time to spare himself. Then they both fought desperately, and moved towards the horse bones, where they had a fierce struggle for a long time. Now the one and now the other was forced to his knees, but in the end the mound-dweller fell backwards, and there was a great crash.

Grettis saga Ásmundarsonar 18 Translation Fox and Hermann Pálsson 1974: 36–7.

The roof-construction of the chamber is exactly paralleled by Stolpe’s findings in the Birka cemeteries, such as the rafters found in grave Bj. 607 (Gräslund 1980: 35). The contents of the mound could almost be a description of the Birka chamber-graves, with the boxes of precious objects and the presence of horses, which the last part of the above passage clearly indicates were slightly separate from the main chamber, again exactly as at Birka.

Fig. 3.12 Grave-goods from the double inhumation in Birka chamber-grave Bj. 834 (after Arbman 1943: 307; drawing by H. Faith-Ell).

Another account to mention a seated person in a mound comes from Njáls saga 78, when Gunnarr Hámundarson is described as sitting upright in the barrow constructed for him. In Gunnarr’s case a chamber is clearly mentioned, as it is lit up by four ‘lights’ which enable the onlookers to see the dead man’s exultant face as he happily sings in his mound (the mention of lights brings to mind the large wax candle found in the chamber grave at Mammen in Denmark, see Leth-Larsen 1991).

One further piece of supporting evidence, though not relating specifically to a chamber grave, is found in Ibn Fadlan’s celebrated account of a Rus’ funeral on the Volga, recorded during his diplomatic mission in 922. As noted in chapter 1, the famous ship burial description and other passages that may concern Scandinavians have been discussed many times and will not be reviewed in any detail here (excellent discussions appear in Wikander 1978, 1985; Foote & Wilson 1980: 407–11; Montgomery 2000; see also my own study of aspects of the text, Price 1998a: 39–42, 2010a, 2012). We can focus here on just one element of the burial rites: Ibn Fadlan makes it clear that the dead man is deposited in the funerary ship on a bier covered with tapestries, but that he is propped up with cushions to a sitting position.

Strangely, all these descriptions were largely ignored by archaeologists until Anne-Sofie Gräslund’s analysis of the burial customs on Birka (1980: 37ff), prior to which the notion that the dead were seated in the chambers had been made only by the original excavator Hjalmar Stolpe (1882: 58–9; 1889: 461) and followed by Arbman as we have seen (1943: 221). Soon after finishing his main excavations on Birka, in the early 1880s Stolpe again encountered seated burials in some of the ships at Vendel, in particular the tenth-century grave IX which contained a man in a chair (Stolpe & Arne 1912: 37). Having reviewed the complete Birka funerary material, Gräslund was able to support Stolpe’s suggestion that seated burial was actually common in the chamber-graves (1980: 37; see also Robbins 2004).

Returning to Bj. 834, we find an impressive array of grave-goods (Fig. 3.12). We know little of the man’s clothes, except that he was wearing a cloak, fastened by a pennanular brooch (4). He had a belt on which were hung a sheathed knife (8), a long fighting knife (6), and a leather pouch containing Arabic coins (14). The latest of these was minted c.917–918.

The woman was wearing a belt from which hung an iron knife (17) and a leather pouch containing more Arabic coins (15) of which the latest provides a terminus post quem of c.913–932 for the construction of the grave (Arwidsson 1986: 166).

She seems to have worn the archaeologically normative Viking-Age female dress, with two oval brooches of type P42 (9), bronze and silver brooches (11, 13) and two faience beads strung between them (10). A ninth-century Arabic coin had been mounted as a pendant and worn on a thread round her neck (12; Audy 2018: 300–1). She was wearing a silk shawl round her shoulders, partly covering the oval brooches. The shawl was edged with a continuous silver-threaded 1 cm-wide brickband of type B3 (see Larsson 2001) and was probably fastened with one of the circular brooches. There were also traces of a very coarse-weave wool (a cloak or blanket?) of unknown location in the grave, perhaps supporting the idea that this was a winter burial.

A number of objects had been placed in and around the chamber. Beside the presumed location of the chair, lying on the floor of the grave, was a sword in a wooden sheath (1). Between the sword and the chair was a collection of female toilet implements: a pair of iron scissors (7) and beside them a pair of tweezers, two awls and a needle-case. Against the west wall of the grave chamber a shield had been leant (3) with its front side towards the wall, and positioned directly in line with the chair; the shield was possibly repaired with a riveted patch (5).

South of the shield, in line with the sword, was an iron staff (2). As in many of the Birka chamber-graves, the objects in Bj. 834 were laid out with some care, aligned at neat right angles to the sides of the grave. The staff as it lay in the grave when found is an exception to this, which suggests that it may have come to rest in this position having fallen from an upright placement against the chamber’s end wall, near the shield which was clearly propped up in this way. Kyhlberg (1980b: 275) suggests that the staff was deliberately placed with its pointed tip under the pommel of the sword, but the field drawing is very ambiguous here and we have no other source – it is not clear that the tip actually is under the sword rather than just touching it, and in any case this position could equally be a chance result of the object falling as the chamber decayed. This object is discussed extensively below.

At the foot of the grave, up against the horse platform, was a riveted wooden box (20), on top of which had been placed a wooden bucket with iron handle and rim mounts (23). Immediately to the north of the box and bucket was another wooden box with iron nails and mounts (24), quite simple though perhaps with a small silver mount. Lying on the floor of the chamber at the east end was a bundle of 15 arrows, probably in a quiver (21). We can probably presume a bow too, now decayed, but lying somewhere nearby on the chamber floor.

The two pairs of crampons (18 & 19), presumably attached to shoes, present a problem. Are these ‘Hel shoes’, the helskór mentioned in Gísla saga Súrssonar 14 as being fixed with special bindings to the feet of the dead to speed their journey to Valholl? They are only mentioned in this one source, but it is interesting that – despite their name – the destination towards which they will aid the wearer’s journey is specifically the hall of Óðinn, not just the realm of the dead in general (see Strömbäck 1961). In the reconstruction drawing I have suggested here that the man was wearing cramponed shoes (find 18, slightly larger than the crampons from find 19), while the woman had no need of them because she would ride to the next world in the wagon implied by the presence of the harnessed and cramponed horses. The footwear represented by find 19 cannot have been worn by either of the people in the chair, and so they are shown here as a separate pair of (woman’s?) shoes, ready for use at the foot of the grave.

Finally, a lance (22) – in the form of its metal head, the shaft having decayed – was found embedded at a downward-sloping angle in the wooden facing of the horse platform, about 15 cm from the floor of the chamber. The head had penetrated some 30 cm into the wood, leaving only 15 cm of iron still exposed, thus indicating that it must have been thrown into the wall with very considerable force. The angle of the head suggests that whoever cast it was standing on the northwest lip of the grave, behind and to the left of the people in the chair, looking from the lance-thrower’s point of view. Other lances from the Birka chamber-graves have been estimated as having a total length of 2.5–3 m (Gräslund 1980: 31); if this figure is applied to the lance in grave Bj. 834 then this would mean that the thrown weapon could have cleared the edge of the grave and the bodies in the chair, and hit the wall at an angle of about 45 degrees, an estimate which also appears to match the angle of the embedded lance-head as shown in Stolpe’s original field drawing. The base of the lance shaft would therefore be almost level with the edge of the grave cut, and the shaft would have extended obliquely across the grave chamber over the people in the chair. The relative chronology of the actions suggested here is supported by the fact that the obstructive presence of the lance would have made it extremely difficult to furnish the chamber after it had been thrown, and it is therefore very likely that the lance was cast into the chamber wall after the grave contents had been arranged, perhaps as the last act before the chamber was closed.

In its totality, the burial in Bj. 834 is hard to interpret, but clearly very special. The presence of the harnessed draught horses suggests an absent wagon, which is almost always a funerary vehicle of high-status women in Viking-Age graves. Does this imply that the woman in Bj. 834 was the most important occupant? The staff is the only object that directly suggests an association with sorcery, but it is one of the four such objects which can be interpreted most securely. The possibility that the dead woman was a volva or similar must be regarded as every strong.

One element in particular is striking – the throwing of the spear into the completed burial chamber. It is important to note that the spear’s trajectory would have carried it over the bodies in the chair, as the Old Norse sources record several instances of this practice. In Ynglingasaga 9, Óðinn declares that all those who are to go to him after death are to be marked with the point of a spear; in Flateyjarbók 11, a spear is shot over an enemy host at the start of a battle, to dedicate them to the god; and in Voluspá 24 it is Óðinn’s casting of a spear over an army that precipitates the war between the divine families (see also Ellis Davidson 1964: 51ff and Turville-Petre 1964: 43 for more examples). The precision of this action is surely comparable with the spear cast into Bj. 834. There would seem little doubt that its occupants were dedicated to Óðinn, the god of seiðr, which would of course fit with the presence of the staff (see Kitzler 2000 and Artelius 2006 for more on Viking-Age spear rituals, including examples from Birka).

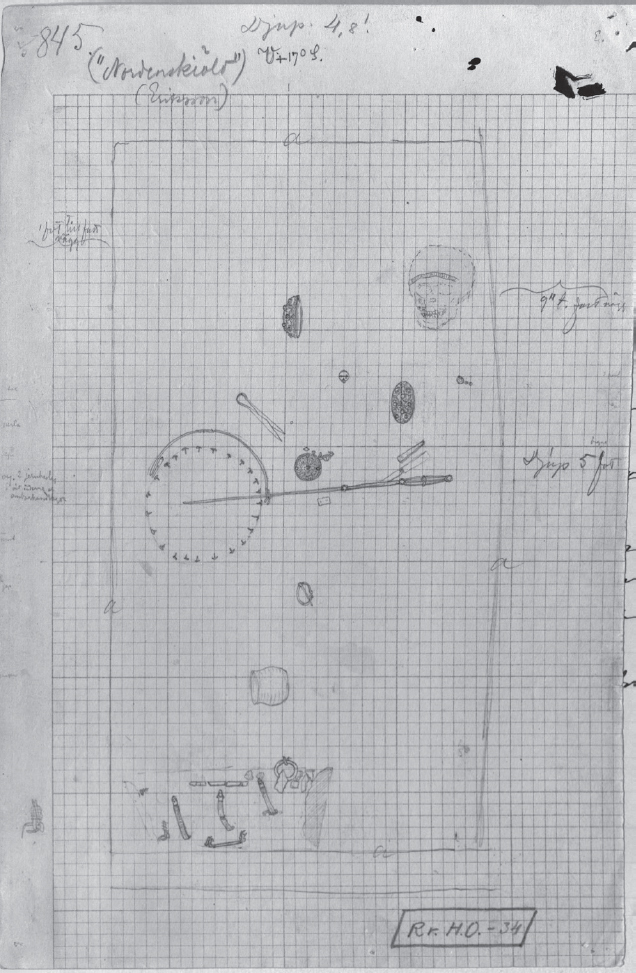

Bj. 845 was a chamber grave under a mound, standing on its own inside the town wall, at the southern end of cemetery sector 1B. From its position relative to the second gap in the wall (counting from the south), it seems likely that the mound post-dated the construction of the rampart and had been raised beside a road leading out of the town.

The chamber was relatively small, only 1.8 × 1 m, and oriented west–east. The walls were lined with horizontally-laid logs, up to a height of 0.45 m above the floor (Arbman 1943: 319f; Figs 3.13–3.15).

Of the skeleton, a nearly complete skull was all that remained. From the size and shape of the chamber, and the position of the grave-goods, there is again a strong likelihood that the dead person – assumed to be a woman – was buried sitting in a chair. This would have been facing east, and positioned roughly central in the chamber with a centre of gravity just east of object 4 on the plan.

On her belt hung a leather pouch (un-numbered), a small whetstone (9) and a small iron knife (10), with silver wire on its handle. She was wearing conventional Viking-Age female dress, including two unique oval brooches of Berdal type (1; see Jansson 1985: 32f, 136) and a large circular bronze brooch (2). Beside the latter was a row of pendants (3; Audy 2018: 302) – two coins and two small oriental pieces – and a glass bead (6), all presumably once strung together on a string. She also wore a small circular bronze brooch (4) and what appears to have been a separate necklace with three beads (8).

Over her dress the woman was wearing a woollen cloak lined and trimmed with beaver fur, and perhaps fastened with one of the circular brooches. Like the woman in Bj. 660, she was also buried with a silver-embroidered silk band 1.5 cm wide (7) around her temples, just above the eyes. We do not know if this was a head-band alone, or if it held a scarf or something similar in place.

Resting across the woman’s knees, with its ‘handle’ pointing towards the north wall, was an iron staff (11). It was probably cradled in her hands. The shaft extended down to the floor on the woman’s right side, where it rested inside a wooden bucket with an iron handle and iron nails around the base (13). Roughly 30 cm high, the bucket stood on the floor of the chamber at the mid-point of the south long wall. The bucket’s handle was standing vertically, resting against the shaft of the staff (see Fig. 3.15).

Fig. 3.13 Plan of Birka chamber-grave Bj. 845 (field drawing by Hjalmar Stolpe, ATA Stockholm, in the public domain)

At the foot of the grave in the southeast corner was a heavily ornamented iron box, studded with nails and with complex animal-head fasteners (16). On top of it was resting an iron ring with a knotted fastening, 5 cm in diameter. No finds were recovered from the box, so it was either buried empty or filled with organic materials – probably clothing. The box has a very close parallel in the Oseberg ship burial, discussed below, where a similar chest contained what appears to be a set of equipment for cultic activities, including a possible staff of sorcery.

On the floor of the chamber south of the chair was a pair of iron shears (5), with beside them a pair of tweezers. These had probably been laid in the woman’s lap. Near her feet a pennanular brooch (14) was found, which may have been placed in the grave as the fastening on a folded cloak which has since decayed. At the east end of the chamber was a ceramic urn (15), resting on the floor just west of the box.

Fig. 3.14 Plan of Birka chamber-grave Bj. 845 (drawing by Harald Olsson after Arbman 1943: 320)

This was the latest of the four ‘staff graves’ at Birka, with the coin pendants providing a terminus post quem of 925– 943 for the construction of the chamber (Arwidsson 1986: 166). Like Bj. 660, the position of the staff indicates that this was a primary requisite of the grave-goods, and testifies to its significance for the dead woman.

The most spectacular of the possible ‘volva graves’ from Sweden was excavated in 1957 on the west coast of Öland, at Klinta in Köping parish. In the Viking Age this was the site of a small beach market, with clusters of burial mounds on the higher ground overlooking the sea (Petersson 1964: ch. 5; Fig. 3.16). At first the archaeological investigation, which took place under rescue conditions and was necessarily somewhat hurried, explored what were thought to be separate grave mounds composed of stone cairns. As the excavation progressed, it emerged that at least two of the mounds formed part of a single, complex funerary act. We shall here focus on the mounds designated 59:2 and 59:3, their numbering following the register of ancient monuments in the parish (the burials were described in outline by the excavator K. G. Petersson in 1958, with an expanded description in his licenciate thesis from 1964; a third report is collected in Schulze 1987: 55–62, 102–12, with further discussions by Svanberg 2003b: 132f, 252f and Hedenstierna-Jonson 2015a).

Fig. 3.15 Reconstruction of Birka chamber-grave Bj. 845 as it may have appeared when the burial was sealed (drawing by Þórhallur Þráinsson).

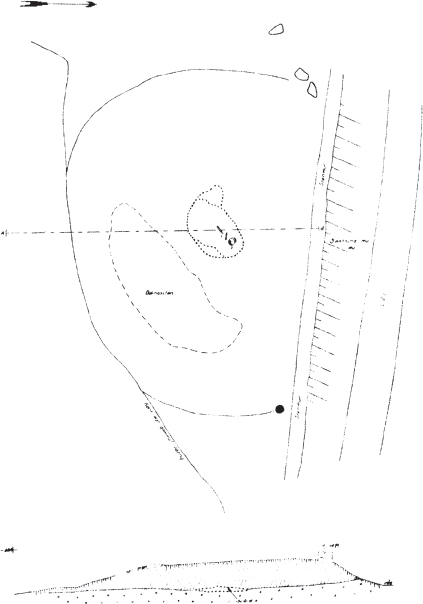

Fig. 3.16 Location plan for graves 59:2 and 59:3 at Klinta, Köpings parish, Öland. The woman’s grave is shown as the black dot (‘det undersökta röset’), while the man’s grave is the mound shown immediately to the north-west of it at the edge of the road (after Petersson 1958: 135; drawing by K. G. Petersson).

Sometime in the first half of the tenth century – a dating based on the artefactual assemblage – two adults, a man and a woman, were cremated together on the heath above the beach at Klinta. The funeral perhaps took place in the autumn, on the basis of rowan berries and hazelnuts found in the ashes. The pyre had been constructed at the very edge of cultivated fields, equidistant between a clearance cairn and the beginning of the tilled soil – perhaps a kind of liminal zone. The two people had been laid out in a boat, which from the quantities of nails and ship-rivets found in the cremation deposits could have been up to 10 m long. Finds of bear claws and paw bones suggest that the dead couple either lay upon one or more bearskins, or were covered by them on the pyre. Around them had been laid a very large number of objects of different kinds, together with the bodies of animals.

Fig. 3.17 Plan and section drawings of the woman’s grave, 59:3, at Klinta, Köpings parish, Öland. In the centre of the mound the cremation pit can be seen, covered by its hexagonal ‘lid’ and the two layers of pyre material and limestone chips. The stones shown at the mound’s north-western edge belong to a Viking Age clearance cairn which was partially buried under the barrow (after Petersson 1958: 136; drawing by K. G. Petersson).

After the fire had died down, an attempt was made to separate and remove the cremated remains of the man and the woman. The woman’s ashes were then buried within the remains of the pyre and a mound raised above them (monument 59:3; Fig. 3.17), while the man’s remains were buried nearby and covered by a second mound (59:2). This interpretation of a double cremation followed by separate burial was first put forward by Petersson (1964: 31f); I agree with his analysis, and refer the reader to his thesis for a detailed review of the stratigraphic background to his suggestion. We can consider these two graves and the evidence for their funerary rituals in detail.

When the human remains had been retrieved, they were washed clean in preparation for their further treatment. At the site of the pyre, the next action seems to have been the excavation of a pit 0.45 m in diameter, placed centrally and dug down through the ash to cut some 0.4 m into the gravel sub-soil beneath. The gravel thus displaced was then built up as a raised ring around the edge of the pit, standing out against the black ashes. The exact sequence of events is impossible to determine, but at or about the same time a substantial portion of the pyre debris was set aside and transported a few metres away to be used to form the adjacent man’s grave.

Fig. 3.18 The urn containing the washed bones of the woman in mound 59:3 at Klinta, Köpings parish, Öland (after Petersson 1958: 139; photographed in situ by K. G. Petersson).

Fig. 3.19 Section drawing through the cremation pit under the remains of the pyre, grave 59:3 at Klinta, Köpings parish, Öland. The urn containing the woman’s burnt bones can be seen at the base of the pit, surrounded by grave-goods; the staff is lying across the top of the pit, covered by the remains of the clay ‘lid’ (after Schulze 1987: 59; from a field drawing by K. G. Petersson).

About 2 litres of the woman’s bones, probably unintentionally mixed with a very small quantity of the man’s remains, were then placed in a small pottery vessel (Fig. 3.18). This was deposited at the bottom of the pit under the pyre. Next to the vessel had been laid the unburnt body of a freshly-killed hen. After this, a number of diverse objects had been packed in around and above the cremation urn, filling the pit (Fig. 3.19):

Fig. 3.20 The two curled copper sheets with runic inscriptions from grave 59:3 at Klinta, Köpings parish, Öland (after Schulze 1987: 109).

•a silver pendant with relief ornament of a kneeling man with two bird-like figures on his shoulders

•a bronze jug, 26 cm high

•a bronze basin

•2 bronze oval brooches of type P51

•2 bronze cruciform mounts

•2 bronze decorated rings

•2 bronze strap-ends

•a bronze trapezoidal mount with interlace decoration and an animal head terminal

•2 copper sheets (Öl 83 and 84), each with one end rolled for suspension and a fragmentary runic inscription (Fig. 3.20):

○-irþn (Nilsson 1973: 242) or -run (Gustavson 2004: 67; Pereswetoff-Morath 2017: 215), probably meaning ‘secret’ or ‘secret knowledge’

○side A: a...f..aþlufalu...þr (Nilsson 1973: 242) or aistrtaubalufalarai (Pereswetoff-Morath 2017: 216), with an undeciperhable inscription on side B; the legible text on side A is possibly a magical formula, but in any case apparently has lexical meaning

•2 pairs of iron shears, one with an attached silver ring

•2 iron knives

•an iron wood-working cramp

•a bearded, slim-bladed battle-axe of Petersen’s Type C

•an L-formed iron key

•25 fragments of a slim iron chain

•2 fragments of iron hook-eyes

•151 beads of carnelian, rock crystal, glass and glass paste

•a Þórr’s hammer ring of iron, badly damaged, with four small Þórr’s hammers

•30+ fragments of iron mounts, probably from an iron-bound bucket

•a bronze fragment of a brooch or part of a reins-distributor

•bronze fragments and melted droplets

•40+ fragments of iron mounts of various forms

•2 rowan berries

When the pit had been filled with objects, and further packed with earth and ash from the pyre, a large metal staff had been laid horizontally across the top. This object can be interpreted as a possible staff of sorcery, but is unique in form even amongst others of its kind, being decorated with animal heads and surmounted with a small model of a building. It is discussed in detail later in this chapter.

Fig. 3.21 Photograph showing the cremation pit before excavation, under the remains of the pyre in grave 59:3 at Klinta, Köpings parish, Öland. The staff can be clearly seen embedded in the remains of the hexagonal clay ‘lid’, as can the bronze jug (after Schulze 1987: 61; photo by K. G. Petersson).

After the staff had been placed across the mouth of the cut, the pit was then sealed in a manner that seems to be unique in Viking-Age excavated contexts. A ‘lid’ had been constructed of grey chalk-rich clay, built around a framework of twigs or bracken, and carefully shaped in a deliberately angular hexagon (in terms of its construction, this ‘lid’ was effectively built like a clay-daub wall). The ‘lid’ was then placed over the cremation pit in such a manner as to cover the shaft of the staff, while leaving the end with the building model projecting out from under it on the northern side (Fig. 3.21).

When these preparations had been completed, the remaining debris from the pyre was swept up and laid over the sealed pit, in a layer up to 0.45 m thick and with a diameter of 2–3 m. This layer of burnt material contained a number of artefacts, the small size of which suggests that they had simply not been retrieved from the smoking ashes.

They included the following, either whole or in the form of burnt fragments:

•an Abbasid silver coin minted for al-Amīn in 801–804

•parts of an equal-armed brooch

•33 beads of rock crystal, carnelian and glass paste

•2 bronze rim-mounts decorated with animal heads

•a circular bronze pendant, badly burnt

•2 iron rim-mounts

•4 iron mounts with pierced triangular decoration

•10 fragments of an iron strip with double rows of punched ornaments

•3 fragments of iron plates with folded edges

•5 fragments of iron rods

•a fragment of a bronze strip

•a fragment of a reins-distributor for a pair of horses

•an iron hook, possibly part of a horse-bit

•a glass linen-smoother

•a charred wooden handle for an unknown object

•fragments of an antler shaft for an unknown object

•iron fragments and melted droplets

•hazelnut shells

This layer also contained the majority of the ship-rivets, 18 whole examples and over 300 burnt fragments.

The ashes of the pyre also contained 14.7 litres of cremated animal bone, the remains of the creatures that had been burnt together with the two people. The exact numbers of each animal could not be determined – and an almost equal amount of their remains had been removed with the ashes for the man’s grave – but among the species represented were horse, cow, pig, sheep, dog, cat and several unidentified birds. As mentioned above, a few bones of a bear were also found but these strongly imply a pelt rather than the whole animal.

The remains of the pyre were then buried in turn under a level surface of limestone chips, spread out evenly over the burnt material. Above this was raised a stone cairn, 13 m in diameter and 2 m high. Granite and limestone blocks up to 0.5 m in size had been placed down first, with the surface of the mound carefully composed of smaller stones which had been laid to form an even dome. The mound had never been covered by earth, and was intended to be seen as a cairn. Its dimensions exactly spanned the zone at the edge of the fields, incorporating the clearance cairn to the north-west and just overlying the agricultural soil to the south-east.

The site chosen for the burial of the man’s remains was 5 m north-west of the woman’s cairn, also within the border zone between the tilled fields and the clearance cairns at their edge (Fig. 3.22). However, his grave was constructed actually adjacent to a large pile of such stones, the whole of which was buried under the mound that was later raised. No pit was made for the man, nor were his remains grouped together. Instead, his cremated bones were mixed up with the debris that had been removed from the pyre, the whole mass of ashes then being spread out in a layer up to 0.25 m thick over a 2 × 3 m area.

Fig. 3.22 Plan and section drawings of the man’s grave, 59:2, at Klinta, Köpings parish, Öland. In the centre of the mound the pile of cremation debris can be seen, secondarily deposited adjacent to a Viking Age clearance cairn which was subsequently buried under the barrow (after Petersson 1964: Fig. 9; drawing by K. G. Petersson).

This burnt deposit contained over 10 litres of cremated bone, almost all of which derived from animals. Only horse and dog were found, which implies that the animals too were separated from the pyre to be laid specifically in each grave. Bear claws and paw bones were again found, suggesting that another pelt followed the man in death.

Only a very small quantity of the ashes belonged to the man. Clearly, very much less of his remains were collected – by comparison with the treatment of the woman, it almost seems as if only a symbolic amount of the man’s bones was buried.

Most of the objects buried with the man were spread out randomly through the burnt deposit. They included the following, either whole or in the form of burnt fragments:

•a silver Abbasid coin minted for al-Mamum, 809–810

•a bronze oval brooch of type P51

•a bronze button

•10 bronze buttons of a different pattern

•4 bronze trapezoidal mounts with interlace decoration and an animal head terminal

•fragments of up to 16 cruciform bronze mounts

•a pair of bronze scales

•over 200 ship-rivets

•a sword, of Petersen type M/E (1919)

○this had been snapped in two before cremation; the pointed end had been buried apparently haphazardly amongst the debris from the pyre, but the part with the hilt had been plunged into the cremation layer and left to stand vertically above it

•8 iron mounts with pierced triangular decoration

•16 beads of rock crystal, gold and silver foil, glass and glass paste

•a bone comb

•a bone needle

•18 gaming pieces – 1 of bone, 17 of Öland limestone

○these had been burnt, but were buried in a wooden, iron-bound and decorated bucket that had probably not been on the pyre

•a semi-circular gaming board of bone

•a slate whetstone

•a fragmentary wooden object, 2.3 cm long and bored hollow

The burnt layer containing the man’s remains was then covered by a stone cairn, 15 m in diameter and 1.3 m high, made up of limestone and granite rocks up to 0.4 m in size with a fill of sand between. Unlike the adjacent woman’s grave, the cairn was covered with turf and would have had the appearance of an earthen mound.

The rituals of which we find the material remains are complex enough, and become only more so when we consider all the probable actions that did not leave such traces in the archaeology. From this and the quality of the artefactual assemblage it is clear that at least one and possibly both of the dead were of considerable status.

In themselves, with few exceptions the grave-goods are not remarkable in the context of such elite burials. We find a range of ordinary domestic items, and also craft-related material: equipment used in textile production, wood-working, and balances for trade (it is interesting that there are no weights). Weapons are present (an interesting absence of spears and arrows), as are the leisure activities of the privileged, in the form of the gaming set. The jewellery is of high quality, and the various buttons and other dress accessories suggest that the clothes of the dead were also impressive. The bear pelt(s) fit in well with this picture.

The various mounts and fragments of decorated bronze and iron also suggest the presence of boxes, chests, buckets and similar items (see the reports on the Klinta grave for detailed parallels for these objects). To this we can probably add a variety of wooden articles, items made of organic materials such as clothing and textiles, and quantities of food and drink. There also seems to have been a full set of horse harness on the pyre, with equipment both for riding and drawing a wagon.

The animals represent all the domesticated creatures on a prosperous farm, together with the horse(s) that could have served both as a draught animal and a mount, the domestic cat and the dog which can to some extent be regarded as animals of the elite. The birds, of unknown species, may also represent hunting activities which were also an attribute of society’s upper strata.

Several singular features are however present in these two burials. Firstly, boat cremations are very rare on Öland, and beyond the small group of them at Klinta (there were three more in addition to that under discussion) only three Viking-Age burials of this kind are known from the island, all from the same site at Karlevi in Vickleby parish; one further cemetery at Nabberör in the north of Öland contains a burial of an unburnt boat (Schulze 1987: 56f). Clearly, on Öland the rite of boat cremation seems to have been exceptional in itself.

The find of a Viking-Age sword is almost unique among Öland graves. The axe is also especially interesting, as it was at least 150 years old when placed in the grave. Probably dating from the Vendel period, though perhaps made as late as c.800, it may have been some kind of family heirloom. We obviously do not know whether the age of the axe was important, but we should perhaps recall here the knife with a broken point mentioned among the volva’s tools in Eiríks saga rauða – perhaps the axe was ‘special’ in some way too? Though the excavator does not comment upon it, in the section drawing of the burial pit it is clear that the axe lay with the blade downwards. The handle would have burned on the pyre so it could not have been swung into the ground, but the manner of its placement recalls the man’s grave, in the ashes of which the sword had been stuck point-down. This ritual is known in four graves from Birka (Gräslund 1980: 76), and Nordberg has collected nineteen more in addition to the Klinta grave (2002: 18f); there are also related examples from Finland, with spears used as coffin nails (Wickholm 2006). Weapons embedded in Viking-Age grave deposits are of several types, sometimes with several in the same burial – a total of 15 swords, 15 spears and 7 axes are known to have been buried in this way. Using a variety of supporting criteria, Nordberg has argued convincingly that the rite was one of dedication to Óðinn (ibid: 20–3), which would apply doubly in the case of the Klinta graves with the sword and axe.

At Klinta, the coins, like the axe, were also old when placed in the grave. Other artefacts from the burial are more individually interesting. The most striking of these, the metal staff with its model building, is discussed below. The jug, which would have been of very considerable value in the Viking period, is of a kind found elsewhere in Sweden and had its origins in the Orient, perhaps in Turkestan or Persia (Petersson 1958: 142 lists the parallels from Gotland, Åland and the grave from Aska in Hagebyhöga which is considered below as another possible ‘sorceress’ burial). The bronze basin probably came from the western European mainland.

The curious silver pendant with its design of a kneeling man also bears closer scrutiny. The object was originally a mount of some kind, re-used as a pendant through the addition of a suspension loop. Several details of the male figure can be discerned: he is shown kneeling in profile, with his head turned to present a full-face view; he has a long moustache, and either a cap with a tassel or perhaps an elaborate hairstyle with a pony-tail; he wears a shirt, belt, widely gathered trousers, and possibly shoes. In his hands he appears to hold long band-like objects, and above each of his shoulders is something that appears to be a bird. Petersson (1958: 143) speculated that the ‘bands’ are snakes, or that they are tethers for the birds, which could then be interpreted as hawks or similar hunting birds.

The image was compared by Petersson (ibid: 143f) to the snake-holding ?woman on the Smiss III picture stone from När parish on Gotland, discussed later in this chapter, and for which both Lindqvist (1955: 45–8) and Arwidsson (1963: 166–70) sought Celtic parallels. The man’s face and the snakes on the Klinta pendant have also been seen in the context of the Aspö rune-rock in Södermanland (Sö 175). None of these seems particularly convincing – if the ‘bands’ are not snakes then half the parallels disappear, and a moustachioed face is hardly a unique attribute in the Viking Age. An oriental origin for the pendant has also been proposed on the basis of a pendant from Birka grave Bj. 791 (Arbman 1940: pl. 95:3), and there are indeed striking similarities here.

A link of the figure to Óðinn, with the birds as Huginn and Muninn, does not seem to have been made. Even if the piece is of eastern origin, there is no reason why its motif should not have been reinterpreted in the context of Nordic beliefs, and I would argue that its deposition in the Klinta grave may well have been understood as a reference to Óðinn. Along with the Þórr’s hammer ring, this would thus bring two gods into the symbolic language of the Klinta grave.

There is also the matter of the separate burial of the two individuals, and the selection of artefacts to accompany them. The man’s grave, 59:2, contained the following combinations:

•conventionally assumptive ‘male’ items

○sword

○set of balances

○gaming set

○elaborate belt set

○large whetstone

•conventionally assumptive ‘female’ items

○oval brooch

○beads

○bone needle

The woman’s grave, 59:3, contained the following combinations:

•conventionally assumptive ‘female’ items

○oval brooches

○beads

○pendants

○shears

○key

○harness for draught horses

○equal-armed brooch (from the pyre debris)

○linen smoother (from the pyre debris)

•conventionally assumptive ‘male’ items

○battle-axe

○wood-working tools

The woman’s grave also contained the majority of the ship-rivets.

With slight reservations, both the excavator and subsequent interpreters have seen the presence of ‘female’ and ‘male’ objects in the graves of the opposite sex as most probably coincidental, a product of an arbitrary division of the grave-goods from the pyre (Petterson 1958: 139 & 1964: 32; Schulze 1987: 58; Bøgh-Andersen 1999: 80). Given the care taken to separate the bones of the two individuals, and the anything but casual division of the majority of the objects, this seems unlikely. The oval brooches, for example, are the size of a human hand, and one of them can hardly have been distributed ‘accidentally’ into the man’s grave. There seems then little doubt that the arrangement of the grave-goods in the man’s and woman’s grave at Klinta was intentional, and therefore presumably meaningful. These distinctions also took other forms, as clearly there was also some reason why the external appearance of the mounds intentionally differed, though this is of course obscure to us. What can this tell us?

Firstly, the deposition of so many objects conventionally associated with the opposite sex is unusual in Viking-Age graves. At Klinta, the woman was buried with woodworking tools and a weapon of war, while the man was buried with female jewellery and needlework tools. The ambiguous gender statements thus made should not be over-interpreted, but it is important to note that they implicate both individuals, and that the two graves are definitely part of the same funerary event. If the woman was a volva or something similar, on the grounds of her staff, then was the man a seiðmaðr or one of the other male users of magic? Sorcerous couples are known from the literature as we have seen, and the Klinta grave certainly qualifies as a case of the ‘special treatment’ that we know such people received in death. We should remember here the sword and axe plunged vertically into the respective cremations.

In a recent study (Lihammer 2012: 193–7; see also Vänehem 2015: 31), as well as in the current (2018) Viking galleries of the Swedish History Museum in Stockholm where some of the finds from the Klinta grave are displayed, the woman has been labelled furstinnan av Öland, which approximates to ‘chieftainess’, almost ‘princess’. The staff is here labelled unequivocally as a völvastav, but also as a kind of sceptre, a symbol of rulership. Whether this is true or not we really have no way of knowing.

Fig. 3.23 The silver pendant in the shape of a man’s head, from the female cremation at Aska in Hagebyhöga in Östergötland (photo by Gabriel Hildebrand, Swedish History Museum, Creative Commons).

In 1920 a small Viking-Age cemetery of six mounds was excavated under difficult conditions at Aska, Hagebyhöga parish, in Östergötland. In Grave 1 was found a cremation deposit beneath a 6.4 m-diameter mound, originally 1 m high and constructed on the site of the pyre. Bones of a woman and a number of animals were found, the latter including a horse, two dogs and a sheep or goat, with a concentration of remains in the centre of the mound. The burial can be dated to the ninth or tenth century (Arne 1932b: 67–82; see also discussions in Graner 2007: 53–62; Larsson 2010: 115f; Andersson 2018: 168–73).

Fig. 3.24 The pendant with a female figurine from Aska in Hagebyhöga, Östergötland; diameter 3.8 cm (photo by Christer Åhlin, Swedish History Museum, Creative Commons).

No detailed disposition of the grave was recorded, but the grave-goods were very rich. They included bronze oval brooches, beads of glass and rock crystal, silver pendants, a silver trefoil brooch and five silver berlocks. The burial also contained an iron kettle and a meat fork, a decorated bone plaque (probably a board for smoothing linen), a number of iron fittings which may represent one or more boxes, and a set of ornate harness for no less than four horses. A bronze jug of Arabic manufacture was also found, of a type very similar to that from the woman’s grave 59:3 at Klinta on Öland. Several loaves of bread had been laid on the funeral pyre.

Three items mark the grave as possibly that of a sorceress. The first of these was an iron staff, which is discussed in detail below. The second was a silver pendant in the form of a man’s head. This object depicts a man with pronounced eyebrows and moustache, long nose and apparently pursed lips (Fig. 3.23). The crown of his head is covered helmet-like by a bird, decorated in Style E from the very beginning of the Viking period or even earlier, resting with its beak on the bridge of the man’s nose (Graham-Campbell 1980a: 141). The piece was clearly old when placed in the grave, and had been adapted for use as a pendant having originally perhaps been made as a mount for a handle of some kind. The object is unlikely to represent Óðinn since it clearly has two eyes, but it may be intended as a depiction of Mímr’s head, or at least understood that way by the woman who owned it, more than a hundred years after it was made. If the iron staff is accepted as a symbol of the volur, then a representation of Óðinn’s personal oracle would fit perfectly with the theme of divination.

Fig. 3.25 A schematic drawing of the pendant with a female figurine from Aska in Hagebyhöga, Östergötland; diameter 3.8 cm (after Arrhenius 2001: 306).

The third remarkable, and unique, object from the Aska grave was a small gilded silver pendant in the form of a seated woman (Arne 1932b: 73; Arrhenius 2001: 306; Figs 3.24, 3.25). Circular in form and only 3.8 cm in size, on the pendant the woman is arranged with her skirts spread out over either a ring or a rectangular object, and it has been suggested that the figure represents a volva on a seiðr-platform, or perhaps a figure of Freyja (Steinsland & Meulengracht Sørensen 1994: 67; Adolfsson & Lundström 1997: 11). The latter interpretation is supported by the woman’s four-strand necklace, which may be intended as the Brísingamen which the goddess obtained from the dwarfs. Several scholars also consider that the figure is pregnant, which would also be appropriate for a fertility deity (Meulengracht Sørensen & Steinsland 1990: 40; Arrhenius 2001: 306). If the pendant does represent either Freyja or a volva, then it may provide us with a unique image of a seiðr-performer in action, sitting composed with hands in her lap, and perhaps with closed eyes.

Despite the poor recording and preservation of the grave itself, the staff and the two unusual pendants combine to make a strong case for the Aska burial as being that of a woman in contact with the supernatural. As with the other graves considered here, the richness of the objects that accompanied her on the pyre also confirm her high status.