In addition to such structures, in the sources for sorcery of a kind clearly-related to seiðr we also find a spatial context which was characterised by an absence of material props. This concept of útiseta, ‘sitting out’, seems to have represented a kind of nocturnal meditation, bringing wisdom and contact with other realms (Strömbäck 1935: 127–36; Hermann Pálsson 1997: ch. 8). We see this in Voluspá 28, quoted in full below: Ein sat hón uti, ‘alone she sat outside’, after which the seeress has gained new knowledge and insight.

The practice is found occasionally in the Old Norse texts, and is again sometimes connected with combat. A classic example, interestingly set by Snorri in a relatively late context, occurs in his Hákonar saga herðibreiðs (16). In the year 1161 as King Hákon of Norway prepares for a decisive battle, his foster-mother Gunnhildr commissions a woman called Þórdís skeggja to sit out in order to secure victory. She replies that if the battle is fought at night, then Hákon will win. Similarly in Orkneyinga saga (65), of a man close to the Earl of Orkney in the twelfth century it was said that, hann var forn mjog ok hafði jafnan úti setið, ‘he was keen on the old practices and had spent many a night in the open’.

The same idea appears in Old High German with hlīodarsazzo, ‘sitting to listen’ (cf. Meissner 1917). The person ‘sitting out’ often did so at a crossroads, or by a gallows under the bodies of the hanged (de Vries 1957: §236). In some way it is clear that útiseta relates to Óðinn’s ability to talk with the hanged, referred to as we have seen in the twelfth spell in the Ljóðatal section of Hávamál (157), in Ynglingsaga (7) and in several of his names. This must be the same valgaldr – the ‘corpse-charm’ – with which the god raises the dead volva to answer his questions at the gates of Niflhel in Baldrs draumar (4), and with which Svipdag does the same in Grógaldr (1).

Though this was a definite Óðinnic marker, widespread belief in útiseta as a mortal practice can be seen as late as the early thirteenth century, when Bishop Bjarni Kolbeinsson of the Orkneys began his Jómsvíkingadrápa thus:

| Varkak fróðr und forsum, | I did not become wise under the running water, |

| fórk aldrigi at goldrum, | I never gave myself to galdr, |

| hefkak ............................. | I have never........................... |

| ......................................... | ............................................... |

| ollunis namk eigi | not at all did I take up |

| Yggjar feng und hanga | the booty of Yggr [Óðinn > poetry] under the hanged |

Bjarni Kolbeinsson, Jómsvíkingadrápa 2; my translation

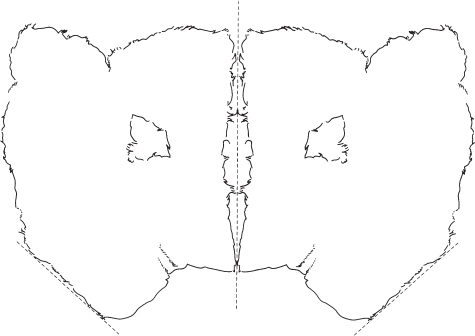

Fig. 3.57 Reconstruction of the costume of Þorbiorg lítilvolva, based on the description in chapter 4 of Eiríks saga rauða (drawing by Þórhallur Þráinsson).

As well as gaining wisdom and inspiration, útiseta has the same sense of summoning something that we will see repeatedly in other parts of the seiðr complex. In the medieval Norwegian Gulaþing laws against pagan practice, this is made concrete when we read that they forbid útisetu at vekia troll upp, at fremia heiðni með því, ‘sitting out to wake up a troll, to perform heathenism by means of it’ (NGL I: 19, 182). Perhaps Þórdís in Hákonar saga Herðibreiðs also conjures some being of this kind, and it is this that would fight on Hákon’s side to ensure victory (as with Þorgerðr Holgabrúðr in chapter 6).

In considering the special clothing of the seiðr-workers, the obvious starting point is the very detailed description of Þorbiorg lítilvolva’s outfit in Eiríks saga rauða (Fig. 3.57). This has already been quoted in chapter 2, but we can reiterate here:

107.enn er. hun. kom vm kuelldit ok se madr er i moti henni uar senndr. þa var. hun suo buin at hun. hafdi yfir sier tygla mauttvl blann. ok var settr steinum. allt i skaut ofan

108.hun. hafdi a. haalsi ser gler taulr. hun hafdi. a haufdi lamb skinz kofra suartann ok vid innan kattar skinn huitt staf hafdi hun. i henndi ok var.a. knappr …

110.hun. hafdi vm sik hnioskv linda ok var þar aa skiodu punngr mikill. varduetti hun þar i taufr þau er hun þvrfti til frodleiks at hafva.

111.hun hafdi kalf skinnz sko lodna a. fotum ok i þveingi langa ok sterkliga. latuns knappar. mikler. a enndvnvm.

112.hun hafdi a. haundvm ser katt skinnz glofa. ok uoru hvitir innan ok lodner.

When she arrived in the evening, together with the man who had been sent to escort her, she was wearing a blue [or ‘black’] cloak fitted with straps, decorated with stones right down to the hem. She wore a string of glass beads around her neck. On her head she wore a black lambskin hood lined with white catskin. … Around her waist she had a belt of tinder-wood, on which was a large leather pouch. In it she kept the charms (taufr) that she used for her sorcery [fróðleikr]. She had hairy calfskin shoes on her feet, with long, sturdy laces; they had great knobs of tin [or ‘pewter’ or ‘brass’] on the end. On her hands she wore catskin gloves, which were white inside and furry.

Eiríks saga rauða 4; text from Skálholtsbók after Jansson 1944: 39–44; my translation

Some aspects of this clothing – the cloak, the glass beads, possibly the hood – are relatively common elements of Viking-Age female dress. Other aspects of her garb are unique, such as the ‘stones’ with which the cloak is set. There are no parallels for this in the archaeological material or the saga sources, and one is tempted to suggest a medieval invention here, suitable for a story-book magician. Many aspects of this description must surely be treated with caution, and not taken as a pattern for the ‘outfit’ of the volur, even were we to assume that they had any form of standardised dress.

However, some aspects of the clothing have definite parallels, and must be taken more seriously. The ‘straps’ on the cloak are puzzling, and these recall the numerous such features found on the jackets of Siberian shamans. The focus on the special belt also recalls other traditions, such as those of the Sámi; again, we shall examine these in the next chapter. The metals may also be important. In the description of Þorbiorg’s shoes, the knobs on the ends of her laces are made of latún, which is variously translated as ‘tin’, ‘pewter’ or even ‘brass’ – we simply cannot be sure which of these metals was intended.

Other descriptions of sorcerers’ clothing are very sparse in the sagas. The volva in Laxdæla saga (76) is wearing a woven cloak when she appears in a dream, and when her grave is opened it is found to contain a brooch or pendant. The spákona Þórdís in Vatnsdæla saga (44) also wears a black cloak, which appears to be more than functional clothing because she instructs a man to wear it when he uses her staff to bewitch an opponent.

Amongst the archaeological material we may think of the silver toe-rings worn by the woman from Fyrkat, and the possible nose-ring found in Birka grave Bj. 660. The silver-embroidered head-bands found in Bj. 660 and 845 may also be relevant in this context, though these are also found in other female graves.

The seated woman on the relief pendant from Aska in Hagebyhöga in Östergötland, who as we have seen may represent a volva, wears two or three layers of long garments with a quadruple row of beads and a large bow-brooch of pre-Viking type (see Arrhenius 2001: 306). Around her temples she bears a thin band, perhaps similar to those found in the Birka graves.

The Old Norse written sources contain almost no direct references to the use of masks or other head coverings in connection with sorcery, but there are a striking number of implicit descriptions of such items. In addition, there is a wealth of evidence from archaeological material.

In the Eddic poems, as we have seen above there is a consistent motif of Óðinn in disguise, reflected in the god’s names. Of these, his aliases as Grímr and Grímnir – ‘Mask’ and ‘Masked One’ – in the Grímnismál are particularly suggestive, especially as he appears to enter some kind of trance in this poem. Similarly, the dead volva who appears in a dream to Herdís Bollisdóttir in Laxdæla saga (76) is wearing a cloth that covers her head like a hood (faldin hofuðdúki). In this context we can recall the possible veil accompanying the woman buried in Fyrkat grave 4 (Pentz et al. 2009: 218f).

We can also consider the famous episode from Íslendingabók, in which Ari recounts the decision by which Iceland accepted Christianity. He describes how the alþing met to debate the new religion, and the Lawspeaker Þorgeirr ljósvetningagoði covered himself with a cloak for a day and a night in order to meditate before announcing his recommendations to adopt the new faith. Jón Hnefill Aðalsteinsson has studied this episode at great length (1978), and concludes that Þorgeirr is communing with the spirits in a ritual act, bordering on a shamanic trance.

In the archaeological sources we have a number of indications of Viking-Age masks, but none of them are unequivocally associated with religion. The most dramatic are two examples found rolled up and used as caulking in a tenth-century ship from the harbour at Hedeby in Denmark (Hägg 1984a: 69–72, 185–8; 1984b; 2001).

Fig. 3.58 The complete felt mask from Hedeby, Fragment 14D, seen flat in the upper picture and also moulded into what is believed to be its original shape (after Hägg 1984a: 71; photo by E. Tams).

The smaller mask, Fragment 14D in the Hedeby textile database, was made of red felt, and measured only 19 × 14 cm in size (Fig. 3.58). If intended for an adult, only the area of the face itself could have been covered, or it may have fitted an adolescent. The mask had pointed ears, a marked elongated snout, eye-holes and sculpted contours for nostrils. The outer surface of the felt had been brushed up to give an appearance of fur. It is difficult to say which animal is represented – dog, sheep or fox have all been suggested.

Of the other mask, Fragment 25, only half was preserved, but as this was one side of the complete object its original form could be reconstructed (Figs 3.59, 3.60). Unlike the smaller mask, this was of a size suitable for an adult, being 26 × 20 cm wide and therefore twice as big when new. Made of dark brown twill, the mask has been suggested to have depicted a bull or cow, and was originally formed with a flat snout, elongated eyes and clearly defined, pointed ears.

Fig. 3.59 The more incomplete of the felt masks from Hedeby, Fragment 25, preserved to half its original form; the mask is seen here as a doubled image in an attempt to reconstruct the complete appearance (after Hägg 1984a: 70; drawing by H-J. Mocka).

Fig. 3.60 Reconstruction of the incomplete Hedeby mask, Fragment 25 (after Hägg 1984a: 70; drawing by H-J. Mocka).

It may originally have been part of a hood that enclosed the entire head, perhaps fixed at the front so the mask itself could be lifted aside or removed.

In her publications on the Hedeby masks, Inga Hägg has made a comprehensive survey of references to masking traditions, and suggests that they might best be seen in the context of the berserkir and ulfheðnar, though she also mentions the Óðinnic Grímr-names.

The Hedeby masks bear interesting comparison with a number of similar pieces found at Novgorod, on the Volkhov river in northwest Russia. At least a dozen masks have been found at various sites around the city, all made of leather and preserved in the anaerobic, waterlogged soils. No full publication has been made of these finds, but of the dozen or so discovered a few have been studied in some detail. The excavators have dated all these objects to the thirteenth century on stratigraphic grounds, but these datings must be treated with some caution in view of the methodologies used when the excavations were carried out.

All the published masks are cut from a single piece of leather, and average around 25 cm long by 20–24 cm wide, large enough to cover an adult face. The eyes and mouth are cut out, and the nose is usually formed as a three-sided flap which would cover the wearer’s own nose and project slightly, rather like the nose-guard of a helmet (see the examples in Perepelkina 1985: 30f). The mouths are often smiling, and with teeth individually cut out of the leather. Some of the masks also preserve traces of paint, either accentuating the eyes, radiating out from the mouth, or sometimes in coloured circles at different points on the face. Another example, made like the others but with clearly formed ears cut in profile at the top of the mask, was found at Novgorod in the early 1990s and published by Rybina (1992: 181f). This has been dated to the late twelfth century, perhaps as late as the beginning of the thirteenth. The use of the Novgorod masks is unknown, though they were clearly not toys. Their sheer quantity is very striking, and they presumably related to some public performances in the early medieval town (perhaps, as we have seen, even as early as the end of the Viking Age).

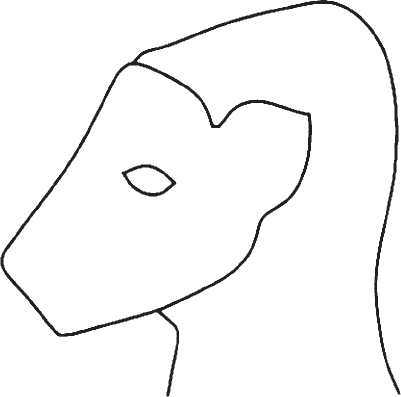

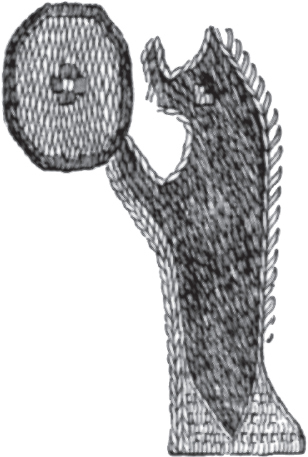

Two strange figures on the Oseberg tapestry may also depict women wearing masks, but they may alternatively represent shape-shifters in animal form. Identified as female by the classic sweeping dress characteristic of women in Nordic iconography, one of these shows a figure with a beaked head like a bird, perhaps a crane (Fig. 3.61). She has either a folded shawl or perhaps a pair of wings wrapped about her. The other figure is shown wearing what appears to be the skin of a boar, with a clearly depicted head and bristles running down the back of its neck all the way to the ground (Fig. 3.62). This latter figure is holding a shield aloft (see Hougen 1940: 103ff; Mannering 2017: ch.6).

Looking at other aspects of Viking-Age material culture, a motif that appears with some frequency in the metalwork and occasionally on runic stones is an elongated, kite-shaped human head often termed a ‘face-mask’ (Fig. 3.63). The motif reached its zenith of refinement in the Mammen style, but examples are known from much earlier artistic traditions. The image is found on various forms of jewellery including pendants and necklaces, on some of which the ‘masks’ are formed as individual silver and bronze pendants strung together. The most lavish example is the early eleventh-century hoard from Fölhagen on Gotland, which we have already encountered above as it contained two miniature chairs. The hoard also included 13 mask-pendants, of which one was designed in a mix of Scandinavian and Slavic styles (Stenberger 1947: 21–4, pl. 170; Jansson 1996: 52ff).

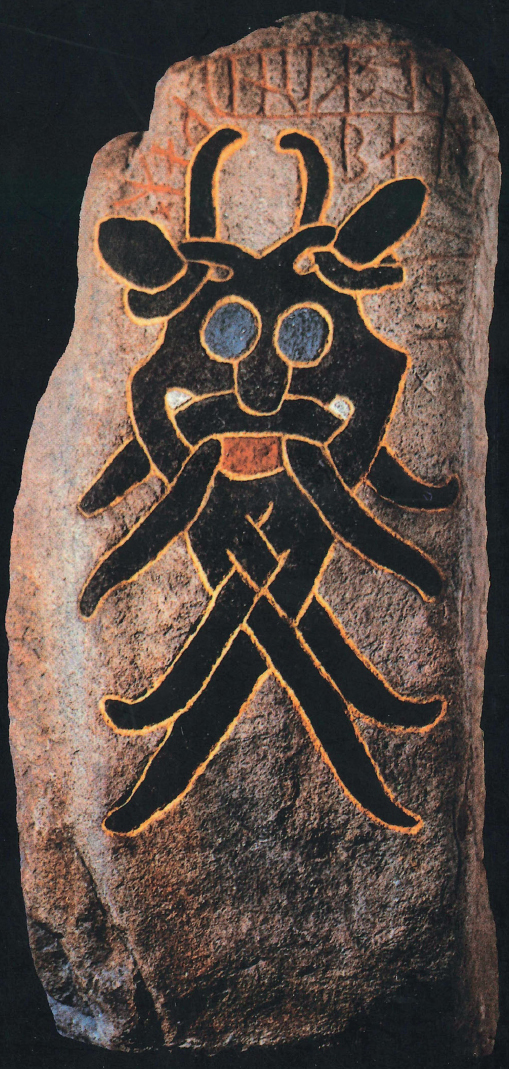

Other such images appear on some of the Gokstad and Oseberg woodwork, on a bone sword-pommel from Sigtuna, and in the decorative schemes of the Cammin and Bamberg caskets amongst others. The face-masks also occur on a number of runestones, particularly in Denmark, of which the clearest example is probably the image on runestone DR 66 from Aarhus (Fig. 3.64). The full corpus of motifs has been assembled by Floderus (1945) and Arwidsson (1963), with a useful discussion by Ramskou (1975).

Several writers, including Dragsholt (1961) and Ramskou (1975: 151f), have suggested that the face-masks represent originals in leather. The interlace is taken to indicate a complex series of folds that would allow the mask to be flexibly fitted to the face (Dragsholt’s paper includes a number of patterns drawn out from the Viking-Age designs).

The problem with these images in the present context is that while they may represent genuine masks, they may equally have been intended as nothing more than faces. We must be careful here not to let the terminology of art historical analysis spill over into interpretations of actual objects. Similarly, the archaeologically-excavated masks tell us little of the circumstances in which they were used. While they appear unlikely to have been toys, they may have been employed in seasonal dances and festivals of the kind familiar from later medieval Europe, rather than used by sorcerers in the course of magical practices. We shall return to this subject of masking and guising in chapter 6, reviewing the important work undertaken in this area by Gunnell, Hutton, Cawte, Back Danielsson and others. Several other archaeological artefacts are also discussed there in the section on the berserkir, including Russian frescoes of masked warriors, the evidence of the Migration Period helmet plaques, runestone imagery and other depictions of masked fighting men.

We must also consider the possible Norse use of another object that in fact forms one of the primary attributes of shamans across the circumpolar region – the drum.

In the textual sources there is one single incident in which such an instrument may be mentioned – the passage from Lokasenna 24 in which Óðinn is accused by Lóki of practising seiðr. The god is said to have draptu á vétt sem volor, ‘tapped on a vétt like the volur’.

Fritzner was an early interpreter of the vétt as a shamanic drum, along the same lines as those common in Sámi culture (1877: 196f), and this idea has been developed at greater length more recently by Kabell (1980). However, this is in many ways a problematic interpretation. Clearly the vétt was some kind of instrument to be struck or beaten, or rather tapped lightly, but it must be emphasised that the most obvious sense of ‘drum’ is purely conjectural. No trace of drums has ever been found in Norse archaeological contexts, nor anything that might resemble a drum-hammer or beater. When one considers the contrast with the Sámi culture area, and the relatively numerous finds of both drums and hammers, this seems strange. Admittedly the Sámi drums have mostly been preserved in ethnographic collections of various kinds, but hammers have been excavated, and several of them are made of perishable organic materials such as antler or bone (see chapter 4). In the light of this, it is surely suggestive that nothing similar should have emerged from the archaeology of the Viking world.

Fig. 3.61 A woman with bird’s head – a shape-shifter or a valkyrja? – from the Oseberg tapestry (after Ingstad 1992b: 245; drawing by Sofie Krafft).

Fig. 3.62 A shield-bearing figure from the Oseberg tapestry that appears to show a woman wearing the skin of a wild boar, or perhaps a female shape-shifter (after Hougen 1940: 104; drawing by Mary Storm).

Another possibility is that the vétt was a kind of lid, for a tub or barrel, as Strömbäck proposed (1935: 22ff) and Dronke concurs (1997: 362). One may recall the buckets present in the ‘staff graves’ such as Bj. 845 and 660 as we have seen above – could these conceivably have been vétt (I am indebted to Lisabet Guðmundsdóttir for this suggestion)? We should note here too that in many parts of the circumpolar world, including Sápmi, drums were quite frequently replaced in the rituals by other objects – pot lids, pieces of wood or anything else on which a beat could be maintained (see chapters 4 and 5). In one case though, the idea of vétt as a drum is reinforced by its use in certain kennings for shields, such as Hildar vett from Þjóðólfr’s Haustlong and referring to the valkyrja Hildr (1; see the discussion in North’s edition, p.14f, and chapter 6 below). Like other shield-kennings, this one clearly suggests the slightly bowed form of the shield, and thus by analogy a drum.

With an obvious caveat against future finds, we may be forced to tentatively conclude that the vétt was not likely to have been a drum, but something else. It is even possible that we have found many of them but do not recognise them, for they may have been objects of everyday use (such as wooden bowls) that took on a temporary specialised function according to their context. Again, there are Siberian parallels here.

Fig. 3.63 ‘Face-mask’ motifs from Viking Age contexts. Top row, left to right: an oarlock from the Gokstad ship; runestone from Aarhus (DR 66); runestone from Skern (DR 81). Centre row, left to right: runestone from Sjelle (DR 62); an ornamented antler object from Køge, Sjælland; the axe from Mammen. Bottom row, left to right: runestone from Västra Strö (DR 335); runestone from Bösarp (DR 258); runestone from Lundagård (DR 314). After Floderus 1945: 35.

Fig. 3.64 A late tenth-century runestone from Aarhus, Denmark (DR 66), decorated with a face-mask in the Mammen style. In the fragmentary inscription a fallen Viking is given a classic tribute by his friends: ‘Gunúlfr and Øgotr and Aslakr and Hrólfr set up this stone in memory of Fulr, their comrade-in-arms. He found death … when kings were fighting.’

There are also other possibilities for some kind of object use for the maintenance of a steady beat during Old Norse rituals. In Ibn Fadlan’s account of the ship cremation on the Volga in 922, a group of men are described as using “shields and staves” to beat in unison before and/or during the sacrifice of a slave-girl (translated in Foote & Wilson 1980: 410). As a passive spectator Ibn Fadlan interprets this as a ruse to drown out the woman’s screams, so that the other slaves present will not in the future refuse to volunteer for sacrifice at their own masters’ funerals. This seems rather unlikely as it would presume considerable stupidity on the part of the slaves, so it may be that the drumming had some other function in the ritual which we do not understand. It is also possible that these are the same men who later have sex with the slave-girl and then actually assist in her death: this would not make sense if they are simultaneously drumming to shut out the sounds of her distress, but the text is quite confusing at this point and such an interpretation is certainly possible. If Ibn Fadlan has understood the scene correctly then they would also have to continue drumming for a very long time, whereas if the shield-beating had some other purpose then it would be consistent for the drummers and killers to be the same. It may be significant that the men with the shields are also the bearers of an intoxicating drink given to the slave-girl before she is taken to the place of sacrifice; this drink and the sexual elements of the ritual are discussed below. Morten Lund Warmind (1995: 134) compares the shield-beating to the vapnatak, the clashing together of weapons that marked decisions taken at the þing. He argues that in the funeral ritual it is a way of hallowing the proceedings, and of marking out a sphere of the sacred.

If the written sources for seiðr-performers are taken collectively, there is no doubt that one object above all others was characteristic of the sorcerer’s equipment – a staff. They appear in various forms and under different names, sometimes linked to specific functions or to the separate terminologies of those who wielded them. These are examined individually below, in both historical and archaeological form, but it is clear that in one sense at least they were seen collectively as part of the material repertoire of magic (cf. Gardeła 2016, discussed more fully in ch. 8 below). This prominence of staffs in the apparatus of Old Norse sorcery is seen in several contexts, of which perhaps the most expressive are the Norwegian law codes from the twelfth century:

Engi maðr skal hafa í húsi sínu staf eða stalla, vítt eða blót eða þat er til heiðins siðar veit.

No man shall have in his house staff or altar, device for sorcery or sacrificial offering, or whatever relates to heathen practice.

Eiðsivaþingslov 1:24 in NGL 1.383

There are three references in the sagas to the staffs wielded by the volur and spákonur. The most detailed of these occurs in the famous passage from Eiríks saga rauða (4) that has been quoted above. Here the staff is simply called stafr, and is described as follows:

ok hvn hafdi staf i hendi ok var a knappr hann var bvinn md mersingv ok settr steinum ofan vm knappin

and she had a staff in her hand with a knob at the top, adorned with brass set with stones on top

Eiríks saga rauða, Hauksbók version, 4: 108–9; translation after Kunz 2000: 658

The phrase describing the location of the stones is ambiguous, and can mean ‘below’, ‘above’ or ‘around’; clearly they are set near the knob, but we cannot be sure exactly where. We are told nothing of how the staff is used, or under what circumstances. The volva Þorbiorg holds it in her hand as she arrives, after which the staff is not mentioned. Bringing it with her, it cannot have been among ‘the things she required to perform seiðr’ that the household provide for her, and it appears more as a symbol of her power. There is no question that it is one of the main tools of her trade.

A second description appears in Vatnsdæla saga (44), also reviewed above, and offers a quite different image of the staff in action and the uses to which it is put. The term used here is stafsprota, meaning something like ‘staff-rod’ or ‘staff-stick’. No indication of its appearance is given, but curiously it has its own name, Hognuðr, with an approximate meaning of ‘Useful’. There are exceptions, but normally objects are only given individual names if they are regarded as being of great worth, examples being swords and other weapons among humans, and almost any kind of object associated with the gods. Here the staff is in the possession of the spákona, Þórdís, and is put to a very specific use. Seeking to convince a certain Guðmundr to agree to the terms of a law suit, Þorkell Þorgrímsson asks the advice of the seeress. She tells him to wear her ‘black cloak’ (kufl minn inn svarta) and take the staff in his hand, and to strike Guðmundr three times with it on his left cheek. As a result Guðmundr becomes slightly confused and forgetful, enough to delay the case and make his claim void, but not sufficient that anyone thinks it odd. Afterwards, the spákona tells Þorkell to strike Guðmundr again with the staff, three times on his right cheek: he then recovers his memory. He does not remember the incident with the staff, but realises that something unusual has happened to cause his sudden drying up in court, saying, ok má vera, at við ramman væri reip at draga (‘it may be that I was pulling on a rope against a strong man’). We may note that there is no mention of any kind of argr behaviour attaching to Þorkell for his use of the staff and the spákona’s cloak.

The third mention comes from a short section of Laxdæla saga (76), and is worth quoting in full as it contains the only description of a volva’s grave. The saga’s heroine, Guðrún Ósvífrsdóttir, has become religious in her old age and prays regularly in nocturnal vigils at the church at Helgafell, in which she is accompanied by her friend Herdís Bolladóttir. One night Herdís has a dream in which a bad-tempered woman appears to her, complaining that Guðrún is tossing and turning on top of her every night, and scalding her with tears. She adds that she has chosen Herdís to convey a message because she prefers her company, though she has a ‘strange air’ about her. On hearing of the dream, Guðrún orders the church floor dug up at the spot where she is accustomed to pray:

Þar fundusk undir bein; þau váru blá ok illilig; þar fannsk ok kinga ok seiðstafr mikill. Þóttusk menn þá vita, at þar mundi verit hafa voluleiði nokkut. Váru þau bein fœrð langt í brott, þar sem sízt var manna vegr.

Underneath they found bones, which were blue [or ‘black’] and ill-looking, together with a brooch and a great seiðr-staff [seiðstafr]. People then realised that a volva must have been buried there. The bones were moved to a remote place, where people were least likely to pass by.

Laxdæla saga (76); my translation

An interesting motif occurs here, in the location of a church above a place with some form of spiritual significance, and the name Helgafell (there are several in Iceland) reinforces this. The fact of the volva’s association with this locality echoes the Spákonufell where Þórdís lived.

A staff also appears in connection with a volva’s divination in quite a different context, in Orvar-Odds saga (2) when it is used – by a man – as a weapon against the sorceress herself. This is one of the few examples of violence directed against a volva by the recipient of a prophecy not to his liking. Prior to the volva Heiðr’s arrival at the farm, Oddr has consistently opposed her invitation, and during her later revelation of the future he has remained hidden under a cloak (perhaps a parallel with Þorgeirr’s actions at the alþing discussed above). The volva asks who is concealed under the cloak, and Oddr emerges carrying a sprota staff. He threatens to beat her with it if she tells his future. When she does so anyway, he strikes her with the staff, drawing blood. Heiðr states that no-one has ever struck her before and leaves, but not before accepting gifts in compensation from the householder.

Presumed staffs of sorcery also appear in two other non-human contexts, interestingly specifying that they were made of iron. The most dramatic of these comes from Óláfs saga Tryggvasonar (33), in an episode describing the supernatural population of Iceland defending the country against a hostile sorcerer. Amongst many apparitions, the one decisive in seeing off the unwelcome visitor is a mountain giant who carries an iron staff (járnstafr) in his hand, the purpose of which is not explained. The passage is reproduced in chapter 6 below. Similarly, in Njáls saga (133), Flósi has a dream vision of a man wearing a goatskin who also carries a járnstafr. The man declares himself to be Járngrímr, an Óðinn-name, and then recites a list of men’s names and a battle poem. The man then strikes the ground with his staff, making a great crashing sound, and disappears. The dream is interpreted to mean that all those named by the supernatural visitor will die.

A probable analogue for the (seið)stafr is a term not found in the Old Norse literature in connection with sorcery, but which can be inferred from the very name of the sorcerers themselves: volva means simply ‘staff-bearer’, and derives from volr, ‘staff’. Presumably therefore, in some circumstances volr could also be used to denote a seeress’s staff. A version of the word occurs once in Skáldskaparmál 18, when the giantess Gríðr lends Þórr her staff called Gríðavolr, ‘Gríðr’s Staff’. Steinsland (1991: 162) calls this a volva’s staff, but this is inference alone. Þórr uses it to help him ford a river, and it appears in Eilífr Goðrúnarsson’s Þórsdrápa as hógbrotningi skógar, ‘the forest’s handy fragment’ (tr. Faulkes 1987: 86) suggesting that he thought it was made of wood. Roberta Frank (1986) argues that it is a symbol of aristocratic power, a theme developed for other staffs by Steinsland (1991: 163–8).

Another Old Norse term that has been interpreted as referring to a staff for ritual use is gandr, first discussed once again by Fritzner in his 1867 dictionary. His citation there refers to a stick or staff, employed especially as an instrument of sorcery either for general purposes or as part of shape-changing rituals. As we have seen in chapter 2, it has also been understood to refer to a whole category of sorcery, and further meanings will be reviewed below. The interpretation of gandr in Norse ritual remains far from clear even now, but here we can confine ourselves to the arguments for its use in the sense of a staff.

Shortly after his dictionary discussion, the suggestion was made that gandr was a Sámi concept that had been loaned into Old Norse, an idea partly based on the Historia Norvegiae discussed below, but this notion was soon disposed of by Fritzner himself (1877: 164). The term occurs in several texts, in contrast to the various stafr permutations, but this may reflect the range of meanings that gandr could convey. Some translators, such as Hollander (1962) and Terry (1990), avoid the issue entirely by rendering it in terms of general magical activity. Others take a definite stance, as with Wilbur’s reading of vítti hón ganda in Voluspá 22/4, which he translates as ‘she consecrated the staves’ (1959). Larrington (1996: 7) gives the same phrase as ‘she charmed them with spells’, but curiously adopts the meaning of ‘staff’ in her version of strophe 29, where she translates spáganda as ‘a rod of divination’ (1996: 8).

This variation is typical of the gandr problematic. By the late Middle Ages and early modern period in Norway, gand had come to hold a number of disparate meanings, summarised by Nils Lid in 1927 (see also Tolley 1995a: 66). These included ‘stick’ in the sense of a cane or staff; ‘swollen ridge around a damaged place on a tree’; and simply ‘magic’, specifically associated with the Sámi and in particular with a special form of doll used to curse a victim and constructed from pieces of wood, hair and nail parings. The latter meaning is almost certainly very late, and matches a class of objects that are familiar from European folklore and late medieval witchcraft over a broad region (see Merrifield 1987 for a range of excavated examples found in house foundations, secreted inside wall-spaces, and so on). However, the sense of ‘staff’ is clear and is found in other contexts which reflect the same meaning, for example as an element in place-names referring to coastal inlets with long, very narrow elongated forms coming to a clear and dramatic point (these include Gandvik in Finnish Karelia, and the Gøndfjord east of Stavanger; Fritzner 1877: 164–5).

The idea that sorcerers rode the staff was also introduced by Fritzner, a notion that quickly broadened into a discussion of the relationship between gandr and seiðr. This has been briefly reviewed in the preceding chapter, and is taken up again in chapter 5, but for now we can concentrate on the debate as to what the gandr actually was. Gustav von Düben argued that it referred to both the staff used by a woman in the practice of seiðr, and the stick ridden by witches (1873: 273). However, this interpretation was rejected on etymological grounds by Fritzner himself, against his own earlier dictionary citation, though he left open the question of an operative link between the two practices (1877: 167–9). De Vries (1931a: 53) built on this to suggest that the very connotation of ‘staff’ itself derives from later traditions of the witch’s broomstick, and does not reflect the meaning of the word in the Viking Age. It is here that the problems relating to the meaning of gandr really begin, for there is also an argument for a ‘staff’ of a kind that was not used for riding. It certainly seems that the first uses of the word in the sense of a witch’s broomstick come in the fourteenth century, for example in Þórsteins saga bœjarmagns when the central character uses a krókstafr, a ‘crooked stick’, to go on a gandreið (see below and chapter 5; also Bø 1960).

Clive Tolley, who has made the most extensive recent study of gandr (1995a), adopts aspects of de Vries’ position, by arguing that it has no primary meaning as ‘staff’ at all. He follows a different line, in which the gandr, plural gandir, are seen not as items of equipment but as helping spirits of some kind; this alternative reading is discussed below. However, even if we accept this idea, the staff argument is refined further by Tolley himself who suggests that we should instead be focusing our attention on the tools used to summon the gandir. It is here that confusion has arisen, he claims, because this instrument was named with a derivative of gandr, namely gondull.

There is a small corpus of compelling evidence that the gondull was something from which the gandir were sent out, but the relevant sources are of quite late medieval date (see Mitchell 2003). They centre upon the records of a court case held in Bergen in 1325, when a woman on trial for witchcraft made the following statement:

ritt ek i frá mér gondulls ondu[m], ein þér í bak bíti, annar í brjóst þér bíti, þriði snúi uppá þik hæimt [heipt?] ok ofund I ride [or ‘thrust’] from me gondull’s breaths, one to bite you in the back, another to bite you in the breast, a third to turn harm and evil upon you.

Diplomatarium Norvegicum IX: 93

The accused witch, Ragnhildr, then added that after singing the above charm one should spit on the enemy towards whom it was directed. It is probable that the ‘breaths of the gondull’ (its spirits?) took the form of wolves, because an almost exactly similar charm that specifies such creatures is recorded in German from another witchcraft trial in Basel from 1407 (Ohrt 1935–36: 202; Tolley 1995a: 69). As we shall see shortly, this fits exactly with other sources on the gandir spirits that might have been summoned. The idea of the witch’s breath as a bringer of doom was known in the Middle Ages, and is also found in kennings which mention breaths from the gondull (Weiser-Aall 1936: 77f; Tolley 1995a: 69f). However, we here face the same problem of interpretation as the ‘witch’s broomstick’ reading of gandr, because the sources can be seen in the context of a much later tradition of witchcraft that has little relation to Old Norse sorcery but which has nonetheless appropriated aspects of its vocabulary. Nevertheless, the idea of this kind of projected malice is not at all unlikely for the Viking Age, and fits with a much wider complex of magical projectiles that are known from throughout the circumpolar region, especially among the Sámi; these are discussed in chapter 4, but see also Lid’s magisterial study of this phenomenon (1958).

Far more convincing to my mind are the sexual associations of the gondull-staff, that may well illuminate the nature of the rituals involved in the summoning of the gandir. These are discussed below in the section on engendering seiðr, but are in themselves sufficient evidence that the gondull really was some kind of tool used in the gandr-seiðr complex. For now, its possible function as the means of summoning and unleashing the gandir (or perhaps gondulls andar) must remain speculation. It should be noted though that Tolley, whom as we have seen has made the most comprehensive study of this matter, is convinced of such an interpretation. On this topic we may lastly add that some support is provided again from Siberian religion, as there are several instances of spirits being summoned by means of a staff; among the Ket, for example, the shaman’s staff had a crossbar on which the invoked spirits could rest (Nioradze 1925: 79).

Another type of staff used in sorcery, the gambanteinn, is known from only two sources, the Eddic poems Hárbarðzljóð and Skírnismál. In both cases the staff is used either by gods or their servants, though previously owned in one instance by a giant (see Steinsland 1991: 162 for the possible significance of this), and it may be that the gambanteinn was a tool only of the highest levels of the ritual community. The name means simply ‘gamban-twig’, and has definite connotations of slenderness and flexibility. In Skírnismál strophe 32, it is made from a freshly-cut sapling, which supports the idea of a slim cane.

The element gamban- occurs once more in Skírnismál, in strophe 33 with gambanreiði (‘gamban-wrath’), and here it is clear that it refers to something of great power or magnificence, even divinity, thus strengthening the association of gambanteinn with the gods. A similar connotation is found in Lokasenna 8, with gambansumbl (‘gamban-feast’; see Söderberg 1984: 59 for further discussion). Some have suggested a reference to divination (van Hamel 1932; Sturtevant 1956;) but this is uncertain and may relate again to the notion of magical potency (de Vries 1957: § 229; the etymology has also been reviewed by Steinsland, 1991: 160ff). The gambanteinn is probably therefore to be understood as ‘twig of power’ or ‘twig of potency’, although the most accurate translation might well be ‘magic wand’ in the original sense of the term, notwithstanding its unfortunate modern connotations of party tricks and story-book wizards.

It is striking that the gambanteinn is used for the same purpose in both poems, namely to drive a person insane. In Hárbarðzljóð 20, Óðinn is given the staff by the giant Hlébarðr, and then uses it to rob him of his wits, to Þórr’s disgust. In Skírnismál 26, more detail is given, when Skírnir, on an errand from Freyr, threatens the giantess Gerðr with a gambanteinn. A full ten strophes (27–36) are then spent describing the extent of the ‘frenzy of wandering madness’ (in Orchard’s phrase, 1997: 52) that will descend upon Gerðr: utterly deranged, she will howl with grief, travel constantly oppressed by hostile supernatural beings of some kind, rejecting food and wasting away in the shadow of the gods’ contempt.

Interestingly, in both poems there is a further dimension of the gambanteinn’s effects, which serves as a background to the infliction of madness, namely a theme of sexual submission coupled with the instilling of an ungovernable lust. In Hárbarðzljóð, Óðinn receives the staff immediately after he has seduced and slept with seven sisters, who are later termed myrkriðor (an interesting parallel to the volva Þorbiorg’s nine sisters in Eiríks saga rauða). This prolonged sexual conquest of sorceresses is described over four strophes (16–19), and the notion that Óðinn has bent the women to his desire is reinforced by his admission that he employed manvélar, ‘love-spells’. It is at this point that the gambanteinn is mentioned.

In Skírnismál the sexual overtones are even more explicit, as is the idea that the gambanteinn forces submission to the wielder’s will. In strophe 26 it is referred to as a tamsvondr, a ‘taming wand’, apparently a synonym for gambanteinn that further illuminates its function: Tamsvendi ek þik drep, /en ek þik temia mun, /mær, at mínom munom. ‘With taming wand I touch you, /for I will make you tame, /girl, to my wishes.’ (trans. after Dronke 1997: 382). The complete surrender of free-will is emphasised in strophe 30, and in 31 and 34 it is further made clear that the victim has no say in her choice of sexual partner, this too being at the wand-bearer’s command.

At least as described in Skírnismál, the gambanteinn seems to have been empowered by the carving of runes upon it, and it is stated that the removal of these marks would reverse the charms thus effected (see also de Vries 1957: §370). In strophe 36 Skírnir names the three runes that he will carve on the gambanteinn, which show more clearly than anything else the nature of the staff’s power: ergi, œði and óþoli. The first of these, ergi, is a problematic concept that is discussed extensively below; as we shall see it is most often used to describe a curious state of being for men, where it has connotations of ‘passive’ homosexuality in the sense of playing the penetrated role in the sexual act. However, when used of women in a heterosexual context, as in Skírnismál 36, ergi refers not to a Norse notion of perversion but instead to an overwhelming lust. Both œði and óþoli refer to burning pains that afflict the genitals, something made clear by their very specific role among the torments of the lecherous in Hell in later medieval texts (Dronke 1997: 413). Both terms have connotations of agony, combined with a ‘sexual itch’ of irresistible desire. The three runes of the gambanteinn can therefore be translated approximately as ‘(Extreme) Lust’, ‘Burning (with genital connotations)’ and ‘Unbearable (Sexual) Need’. Their place in the complex of Old Norse sexual spells is discussed in Dronke’s introduction to Skírnismál (1997: 398f).

The gambanteinn thus emerges as a particularly terrible weapon, employed by the highest levels of the sorcerous hierarchy within a narrow range of sexual and violent functions.

It appears that the staff not only played a central role in seiðr and its associated rituals, but also that there were different types of staff, used by specific individuals for specific purposes. We may summarise them as follows:

•an attribute of the volva

•implied use in the course of summoning varðlok(k)ur spirits, and for divination?

•an attribute of the volva

•could be very large

•an attribute of supernatural beings?

•an attribute of the spákona

•used to strike an enemy directly, on the face

•used to rob an enemy of his memory, and to instil mild confusion

•implied use in divination?

•no direct information, but can be inferred to have been used generally by the volur

•distinct phallic connotations

•probably used for summoning gandir spirits, and their release for clairvoyance or prophecy, and sometimes the infliction of injury on others

•associated with the working of sexual magic (either sorcery with sexual objectives, or sorcery involving sexual acts in its performance)

•possibly used for riding, especially with intent to bring injury to one’s enemies

•used for severely disordering an enemy’s mind

•specifically employed for instilling both uncontrollable lust and (sexual) subservience to the wielder of the staff

•possible, though doubtful, connotations of divination

Thus once again we see the connection between violent or aggressive sorcery and sexual themes, furthermore associated with specific instruments for the implementation of such magic.

The question as to exactly how the staffs were used in the seiðr rituals is, in one sense, impossible to answer: we simply do not know, and the surviving sources do not tell us. However, there is a possible solution to be found in the ethnographic analogies that can be drawn from the other circumpolar cultures; this will be considered in chapter 5. A second line of enquiry concerns the sexual aspects of the seiðr complex; these are discussed further below.

From their literary descriptions we can see that the various forms of staff differed quite markedly in appearance. There are no explicit descriptions of a gandr or gondull, only circumstantial evidence that they came to a sharp point and were probably made of wood. The gambanteinn was made of wood, appears to have been quite slender, and was perhaps carved with runes; this was probably the smallest of the staffs. The volr may also have been wooden. The stafr was fitted with brass and set with ‘stones’, and had at least one knob; there is no indication of the material used for the main shaft. The seiðstafr could be quite large. As their name implies, the two járnstafr held by dream beings and giants were made of iron.

It cannot be emphasised too strongly that these descriptions are unlikely to be exact, notwithstanding the source-critical problems associated with their saga contexts, nor are they necessarily representative. There is no possibility to exactly match archaeological finds with these objects – in the circumstances we must also add source criticism of the material culture to that of the literary evidence. However, we can use these descriptions to isolate archaeological finds which might reasonably be placed within the general category of staffs of sorcery.

These principally concern a number of iron staff-like objects found in graves from all over Scandinavia (principally western Norway), all differing slightly in appearance but with common characteristics. A small number of comparable pieces are also known in wood. All these are collected and presented below, beginning with the ‘type-examples’ from Birka, Klinta and Fyrkat, after which some general observations are made on their interpretation. This is followed by a catalogue of all the other known examples (with updated detail and references from Gardeła’s subsequent listing, 2016: 268–347; see chapter 8 below).

Three of the staffs from Birka are discussed by Greta Arwidsson (1986), Bøgh-Andersen (1999: 71–6) and Ingunn Ásdísardóttir (2007: 94–7); note that prior to Gardeła’s 2012 re-evaluation, this was believed to be the entire corpus from that site, as discussed above. Due to their common qualities they build a ‘Birka type’ somewhat distinct from the other examples discussed below, while the knob-like mounts on the shafts are paralleled only on the staffs from Klinta, Tuna, Fyrkat and two from Russia (Fig. 3.65).

As described above, the staff that in fact derives from chamber grave Bj. 660 was rediscovered by Gardeła and Andersson in 2012. It now consists of 13 iron fragments and a single bronze mount (Figs 3.66, 3.67). These are too badly corroded to reconstruct the object in terms of length and quality, but provide enough data to correlate with Stolpe’s field records. It is also clear that the staff was of the same broad type as the other three, better-preserved examples from Birka.

When first discovered, the staff that has now been confirmed as coming from Bj. 760 was approximately 0.75 m long (Arbman 1940: pl. 125; 1943: 232), though now only 0.45 m survives in a very poor state of preservation (Gardeła 2016: 326–329). The point is missing, and so the staff was originally even longer. The shaft is of square-section iron, 1 cm in thickness, and at some point along its length once had a four-sided knob. The latter was found loose in the grave detached from the shaft, so its original position along its length is unknown; the knob is now lost. The ‘handle’ is 14.5 cm long, and consists of six round-section iron rods compressed quite tightly around the shaft (Fig. 3.68). Where the ‘handle’ meets the shaft is a mount in the form of an animal head, with the shaft emerging from its jaws. Its eyes are moulded in detail, and the head is decorated with circle-and-dot ornament. At the mid-point of the ‘handle’ is a composite mount consisting of five decorated bronze plates fixed around the shaft to give a faceted appearance. The plates are decorated with punched dots in lines following the axis of the staff. The terminal of the ‘handle’ is a polyhedral bronze knob with indistinct decoration. From this emerges a small flat plate, but this is too corroded to make out any detail.

Fig. 3.65 The three possible staffs of sorcery from Birka graves Bj. 760 (marked 3a–d, and wrongly designated to Bj. 660), 834 (1a–b) and 845 (2a–c), photographed in the late 1930s; all three objects are in a poorer state of preservation today (after Arbman 1940: pl. 125).

Fig. 3.66 The 13 iron fragments from the staff in Birka grave Bj. 660, rediscovered in the Swedish History Museum in 2012 by Gardeła and Andersson (photo by Gabriel Hilderbrand, Swedish History Museum, Creative Commons).

Fig. 3.67 The bronze mount from the staff in Birka grave Bj. 660, rediscovered in the Swedish History Museum in 2012 by Gardeła and Andersson (photo by Gabriel Hilderbrand, Swedish History Museum, Creative Commons).

The staff from Bj. 834 was 0.77 m long when found, though now only 0.57 m remains (Arbman 1940: pl. 125; 1943: 305ff; Gardeła 2016: 330f; Figs 3.69, 3.70). Its original length was probably greater, as the point had already corroded away when it was discovered. The iron shaft is approximately 1 cm thick and square in section, with two polyhedral knobs of bronze with circle-and-dot decoration located respectively 0.19 m and 0.44 m from the base of the ‘handle’. The latter, which is 10.7 cm long, is formed of ten twisted iron rods of which one is now missing, joined above and below by a polyhedral bronze knob of the same kind as those on the shaft (Fig. 3.71). All the knobs were decorated with four circle-and-dot designs on each four-sided facet, except for that at the point where the ‘handle’ joins the shaft, which had five such dots. At the mid-point of the ‘handle’, the rods are encircled by a bronze band engraved with a repeating diamond pattern.

Fig. 3.68 The staff from Birka grave Bj. 760, originally misattributed to Bj. 660 (photo by Gabriel Hilderbrand, Swedish History Museum, Creative Commons).

Fig. 3.69 The staff from Birka grave Bj. 834, as found and reconstructed (after Bøgh-Andersen 1999: 74; drawing by Håkan Dahl, used by kind permission).

Fig. 3.70 Detail from one of the shaft mounts on the staff from Birka grave Bj. 834 (photo by Christer Åhlin, Swedish History Museum, Creative Commons)

Fig. 3.71 Detail of the ‘handle’ of the staff from Birka grave Bj. 834 (photo by Christer Åhlin, Swedish History Museum, Creative Commons).

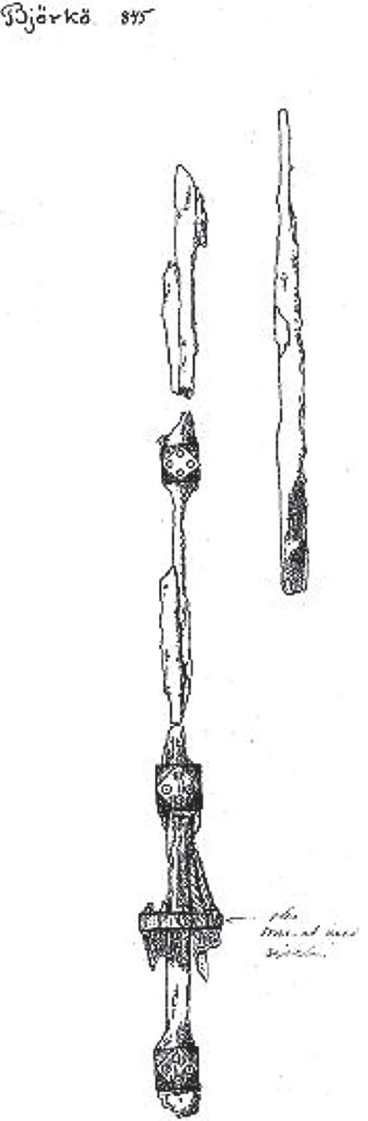

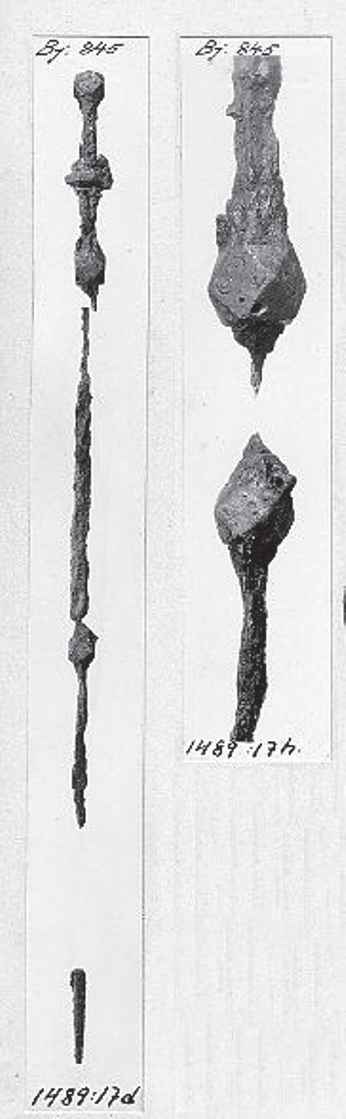

The staff found in Bj. 845 was in very fragmentary condition when discovered (Arbman 1940: pl. 125; 1943: 320; Gardeła 2016: 332f; Figs 3.72, 3.73). According to Stolpe’s field drawings, its length when found was approximately 0.7 m. The shaft is again four-sided and about 1 cm in thickness, tapering to a point. The 14 cm-long ‘handle’ was very damaged, but it appears that it once had ten iron rods bowing out around the central shaft in a ‘basket’ form. At the mid-point, the rods passed through a perforated bronze disc which maintained the even form of the ‘handle’. Like the staff from Bj. 834, the rods were joined above and below by polyhedral bronze knobs with four circle-and-dot decorations on each four-sided facet. The knob at the point where the ‘handle’ meets the shaft is drilled completely through in two places on opposite sides of the polyhedron. These holes are approximately 1.5 mm wide, and could have held nothing thicker than a thread or very thin wire; nothing was found attached to them. Another knob of the same kind as those on the ‘handle’ was fixed to the shaft 0.14 m below the ‘handle’. A small triangular plate projects from one of the polyhedron’s facets, on the side nearest the ‘handle’. The plate is perforated with a single hole, about 1.5 mm in diameter. Again, nothing was found that might have been attached to it.

The staff from the double grave at Klinta on Öland is also a special case. When found its total length was 0.82 m, but one end had been broken off and it is clear that originally the object was longer – perhaps substantially so if the tapering profile was projected to a point (Gardeła 2016: 342ff; Andersson 2018: 180–4; Fig. 3.74). The staff had been badly affected by the fire of the cremation and was broken in several places.

The shaft is square in section, and up to 3 cm on a side. 52 cm from the broken end of the staff is a ‘basket’-like construction 18 cm long, made of four iron rods curving out from the shaft and then rejoining it. At the point where each rod joins the shaft, both above and below, it is gripped in the jaws of a small bronze animal head, resembling a wolf – eight heads in all. On the shaft, 7.5 cm below the ‘basket’, is a polyhedral bronze knob.

Fig. 3.72 The staff from Birka grave Bj. 845 (drawing by Harald Faith-Ell, Swedish History Museum, Creative Commons).

Fig. 3.73 The staff from Birka grave Bj. 845 (photo by Harald Faith-Ell, Swedish History Museum, Creative Commons).

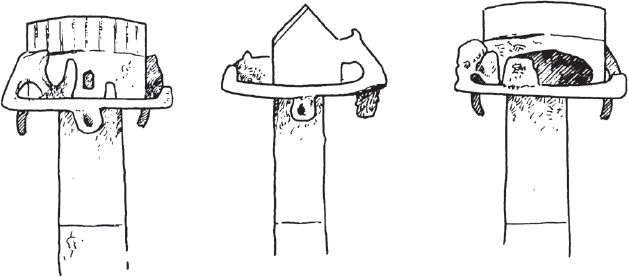

Above the ‘basket’ the shaft continues for 8 cm until the staff terminates in a flat bronze plate, 4 cm square with slightly concave edges. On top of this is a bronze model of a building, apparently a hall of the kind known from the Trelleborg-type enclosures and elsewhere in the Viking world (Figs 3.75, 3.76). The building has a ridged roof apparently covered with planks, and wall buttresses along the long sides which each have a central door (in passing, we can note that this object forms one of the very few contemporary images of a building from the Viking Age and has been widely used in reconstructions). On each corner of the bronze plate sits an animal of some kind – only one is now preserved – stretching up to the eaves of the building. Underneath the bronze plate, from the mid-point of three of the sides (and probably originally the fourth), there extends a small loop of bronze with an eye about 2 mm in diameter; what, if anything, was attached to these is unknown. Only one similar object is known, a square and heavily decorated bronze plaque from the Roskilde area (Christensen 2015: 94f) that also has a three-dimensional building model placed centrally, and with what appear to be birds at each corner; although described as a ‘brooch’, the object has no fittings for a pin on the reverse, and it is possible that this too is the top of a staff of the Klinta type; it is accordingly marked as such on the distribution map.

Fig. 3.74 The staff from grave 59:3 at Klinta, Köpings parish, Öland (photo by Gabriel Hilderbrand, Swedish History Museum, Creative Commons).

Fig. 3.75 Three views of the miniature building on the staff from grave 59:3 at Klinta, Köpings parish, Öland (after Schulze 1987: 109).

Fig. 3.76 Detail of the miniature building on the staff from Klinta, Köpings parish, Öland (photo by Gabriel Hilderbrand, Swedish History Museum, Creative Commons).

Interpretations of the staff’s function have varied. All have compared it to the Birka staffs, and to their suggested functions discussed below, but Mårten Stenberger (1979: 713) saw it as a status symbol or a cult object. Bøgh-Andersen (1999: 77–80) interprets it as a meat spit. The excavator, K. G. Petersson, suggested that the Klinta staff had a parallel of sorts in the iron ‘standard’ from the ship burial in Mound 1 at Sutton Hoo (1958: 147) – a notion discussed in turn in the Sutton Hoo report (Bruce-Mitford 1978: 427f). Both objects have a ‘cage’ of iron bars with animal heads at the terminals, and both are similarly puzzling, but the resemblances are not otherwise close. The most obvious parallels are the Birka staffs, with the ‘basket’ construction and the polyhedral knob, though the Klinta piece remains unique for its size and for the building model.

In view of its parallels, and the extraordinary nature of the grave in which it was found with its elaborate rituals and gender-crossing artefact correlations, there is no doubt that the Klinta staff may be viewed in the same context as other possible staffs of sorcery.

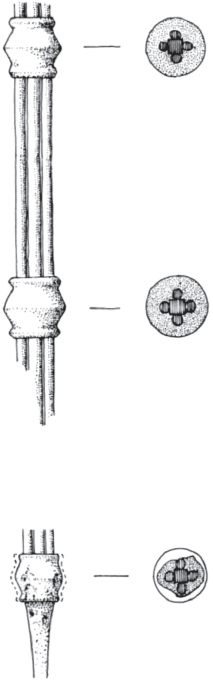

The fragmentary staff from grave 4 at Fyrkat was in two pieces, and so badly corroded that both ends of both sections were missing (Roesdahl 1977a: 97–101; Gardeła 2016: 345ff; Fig. 3.77). Its original length is unknown, but the surviving fragments are very small indeed, being only 7 cm and 2.5 cm long, and about 1 cm in diameter – approximately the dimensions of a thick pen. Almost nothing survives of the object today, its condition being so poor when found, and most of the details described here have been discernible only through X-ray analysis. The link to the other possible ‘sorcery staffs’ comes from its construction and appearance, and its presence in the grave of a woman who on several other grounds might be considered to have been in contact with the supernatural.

The Fyrkat staff is composed of a central iron rod, square in section, bonded on each side with four thinner, circular rods, also of iron. On the longer fragment are two copper alloy knobs, spaced 3 cm apart, through which the five rods are drawn. On the shorter fragment is a single such knob, one one side of which the rods have been fused together into what appears to be a tapering point (this is somewhat unclear on the X-ray, and the end of the ‘point’ is also missing).

The writers of the Fyrkat report do not make a firm interpretation of the staff, but Roesdahl (1977a: 143) does note its similarities with ‘meat spits’ of the kind found in Norway, of the Birka type. It should be noted that this was before anyone had suggested that these latter objects might instead be staffs of sorcery. I agree with this comparison, though Roesdahl also rightly points out that the knobs are almost identical to those on a mount from the front of a tenth- or eleventh-century reliquary from Viborg (1977b: 27–30). The comparison with another box is compelling: was the Fyrkat ‘staff’ actually mounted as decoration on the oak chest itself? One argument against this is that the chest was poorly made and further embellishment perhaps less likely. With a cautious reservation, in the light of the examples considered here and the other objects in grave 4 at Fyrkat, I feel it is justified to include this piece with the rest of the possible ritual staffs. Little more can be added on this fragmentary object, except to note that its slight variation from the other staffs in construction and design – the tapered end especially – may enable us to slightly expand our typologies for magical tools of this kind.

Fig. 3.77 The surviving fragments of the metal staff from grave 4 at Fyrkat, drawn from X-ray photographs (after Roesdahl 1977a: 100; drawing by Flemming Bau).

One of the earliest descriptions of these objects that we possess is found in Hjalmar Stolpe’s field notes from his excavations at Birka, which produced (as we now know) four such finds. Typically sensible, he showed more caution than all subsequent interpreters and freely admitted that he did not know what they were, calling them simply ‘iron objects’.

This aside, most other early interpretations all centre around the notion that they were spits for roasting meat, an idea put forward in the 1880s by Lorange and later supported by all the main Norwegian Iron Age specialists of the late nineteenth century including Undset, Gustafson, Shetelig and Bøe. This was expanded upon by Petersen in his catalogue of Viking-Age tools from Norway (1951: 425–9).

Other scholars, such as Rygh (1885), saw them as fragments of lamp-stands, and they have also been interpreted as whip shanks (Brøndsted 1936: 196). Both of these interpretations were proposed in relation to fragmentary examples, and at a time when few other objects of this kind had been published. Neither author had much in the way of comparative material against which to assess his suggestions. When the whole corpus of the objects is reviewed today, some of them in complete condition, it is quite clear that neither of these interpretations is tenable.

Another popular early interpretation of the staffs was as measuring rods, an idea reinforced by the fact that several of them approximated an ell (aln) in length. This suggestion was offered by Emil Ekhoff for the Jägarbacken staff in 1896 (Hanson 1983: 8), and it seems to have been Arbman’s preferred explanation for the Birka staffs (1943: 278, 305, 320). It is certainly the case that the staffs bear some resemblance to surviving late medieval measuring rods of this kind, which until recently were fixed to the doors of Gotlandic churches (Carlsson 1989: 19ff). Because the Viking-Age examples were overwhelmingly found in what were assumed to be the graves of women, it was proposed that the staffs were probably for measuring out lengths of cloth, the production of which was arguably a female occupation.

A variation on this theme was presented by Ola Kyhlberg in his doctoral thesis, which included a design element on one of the staffs that had hitherto gone unnoticed (1980b: 274–8). He generally follows the idea that they were used to measure length, but on the staff from Bj. 845 he notes the presence of the small perforations on the shaft mounts, one of which is bored through a triangular plate extending out from the knob. He argues that these were for the attachment of some kind of extra element, which was used at right angles to the main shaft as a means to measure volume, either in vessels or of general packaging (ibid: 275). Citing a range of measuring systems from prehistory to the post-medieval period, and taking up the earlier ideas on the staffs as ell-lengths, Kyhlberg suggests that the three staffs are broadly equivalent to the Swedish ell (the reaassigned Bj. 760), 16 inches (Bj. 845) and the Sjællandic ell (Bj. 834), and that they may have been used to create standardised forms of vessel (ibid: 275).

The implications of this interpretation have not generally been taken up in Viking studies, though the idea of the staffs as units of measure has been followed by Nils Ringstedt in his economic studies of the Birka chamber-graves (1997: 135–44). One difficulty is the lack of standardisation, which would seem to be a requirement for a system of standards. Every staff is different, including those that have perforations or similar features (see the list of staffs below). In favour of the interpretation is the fact that the Scandinavians undoubtedly possessed sophisticated economic measurement, as we see in the ring-money of Scotland, the various coin standards in the later Viking Age, the systems of hacksilver, and not least in the weights which form the main focus of Kyhlberg’s 1980b study. The staffs could indeed be a part of this, but as Kyhlberg himself emphasises (ibid: 277), this must remain hypothetical. Ingrid Gustin’s more recent work (2004, 2010) on the staffs as units of measurement is discussed in chapter 8 below.

The most recent interpretation to have been proposed for these objects is the one of most relevance here – namely that they were staffs of sorcery. The text that follows takes this discussion up to the publication of the first edition; see chapter 8 for the works that subsquently took up this theme, sometimes in interesting new directions.

It had long been noted that some of the staffs were likely to be status symbols of some kind, and that their dignity suggested something more than a mundane purpose – Stenberger’s comments on the Klinta staff are typical of this. Building partly on earlier works by Tove Hjørungdal (1989, 1990) which are discussed below, the first lengthy articulation of the idea was presented by Gundula Adolfsson and Inga Lundström in conjunction with their exhibition Den starka kvinnan: från völva till häxa (‘The powerful woman: from völva to witch’, set out in two different works of the same name, of which the most recently published was written first and should be read in that light: Lundström & Adolfsson 1995: 21; Adolfsson & Lundström 1997: 13f).

Three criteria are put forward by Adolfsson and Lundström for interpreting the staffs in this way (1997: 13):

•their appearance and close affinities with each other, and in relation to the literary sources

•the concentration of their find-spots to areas with Frö/ Frej place-names and labyrinths

•the concentration of their find-spots to the Vestland of Norway, where they consider women to have had a strong role in ‘pagan cult’

The first of these receives very great support in the excavated material. Not only do the objects match the written descriptions of the seiðr staffs and their analogues, they are found almost exclusively in what seem to be the graves of women of very high status, in several of which are other artefacts which may have had a connection with sorcery (‘charms’, narcotics, and so on). We also know from Laxdæla saga that the volur could be buried with their staffs.

Adolfsson and Lundström’s other two criteria are less convincing, relying on a decidedly partial reading of Scandinavian prehistory that traces a decline from egalitarian Goddess-worship (“in the beginning men and women are equals”) to the chauvinist oppression of Christianity (“this is the beginning of the end of the culture that worships life and love without sin” – Lundström & Adolfsson 1995: 5). To be fair to the authors, they make their political intentions with the exhibition abundantly plain throughout their two publications. An explicitly feminist vision of the later Iron Age is to be welcomed, though the misogyny of the early church has been questioned by scholars working on the phase of conversion in the North (e.g. Gräslund 2001a: 84; 2003). The problems arise when such an exercise lets its message distort its material, which in turn weakens the message. This is not the place to list the inaccuracies in these publications, but with respect to the staff criteria we can note that there is no proof whatever that prehistoric labyrinths were connected to fertility rituals, and the notion that Vestland women were cult leaders relies on Volsa þáttr and little else. When it was mounted in Stockholm the exhibition raised considerable protest, not least from those who felt that its simplifications did a disservice to its stated aims (see, for example, the multi-part newspaper debate in Svenska Dagbladet 6–11.4.97).

Den starka kvinnan was produced with good intentions, and it included much that was innovative and ground-breaking. Leaving aside its other qualities, the exhibition also made a crucial contribution to Viking studies in that for the first time the figure of the volva was given centre stage, in a manner never seen before in publications or public media. At a specific artefactual level, the interpretation of the staffs as tools of sorcery was established at the same time. It has been repeated since then in several archaeological works, discussed below and in the following chapters.

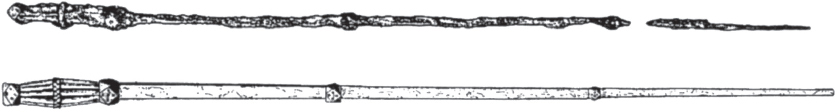

Of course other interpretations are still current, and today the meat spit has not quite disappeared; it should also be noted that this kitchen item can in itself be seen as a metaphor for power and the materiality of social elites (Isaksson 2000: 27f). Susanne Bøgh-Andersen (1999) has published a comprehensive licentiate thesis on Vendel- and Viking-Age roasting spits, with a catalogue of all known finds in the North. She has divided the spits into four types, I–IV, with two variants of type III (ibid: 56, 114; Fig. 3.78). Of these, types I and IV are without question objects for roasting, and are not considered further here. Her type II is extremely simple – essentially a straight, pointed iron rod – and thus could potentially have purposes beyond or instead of skewering meat, but the possibilities are so wide open that there is little we can do. As a proviso, however, one should consider her catalogue of examples (Bøgh-Andersen 1999: 46f) as a wider background to what follows.

Fig. 3.78 Susanne Bøgh-Andersen’s classification system for Nordic roasting spits of the Vendel and Viking periods; types III-M and possibly III-U are here reinterpreted as staffs of sorcery (after Bøgh-Andersen 1999: 114, used by kind permission).