For our purposes the closer interest comes with Bøgh-Andersen’s type III, formed essentially as a straight metal rod with a point at one end and a handle at the other. The two sub-types concern the form of this handle, with either a simple knob or mount differentiating it from the rest of the shaft (type III-U) or an actual handle construction formed of a ‘basket’-like cage of bars bowing out from the shaft (type III-M). It is this ‘basket’ that we have seen on the staffs from Birka and Klinta, which are placed by Bøgh-Andersen as meat spits in her class III-M (ibid: 71–80). The question as to whether these objects of her type III actually are meat spits is central for a discussion of possible staffs of sorcery.

Throughout her thesis, not least in the title itself, Bøgh-Andersen acknowledges that these objects are not merely functional tools for food preparation. Her opening chapters and conclusion all stress this, and indeed she discusses the staffs with very developed ornamentation – such as those from Birka and Klinta – in terms of status and appearance. Bøgh-Andersen’s work clearly focuses on the roasting spits themselves, however, and this tangential argument is not taken to its logical conclusions. The problem is not that she has misinterpreted the meat spits that form the bulk of her useful study, but that she does not develop the idea that some of the more elaborate objects are not ‘symbolic’ spits at all – they are something else entirely, with resemblances to the spits (the same point was made in a review by Holmquist Olausson, 2002).

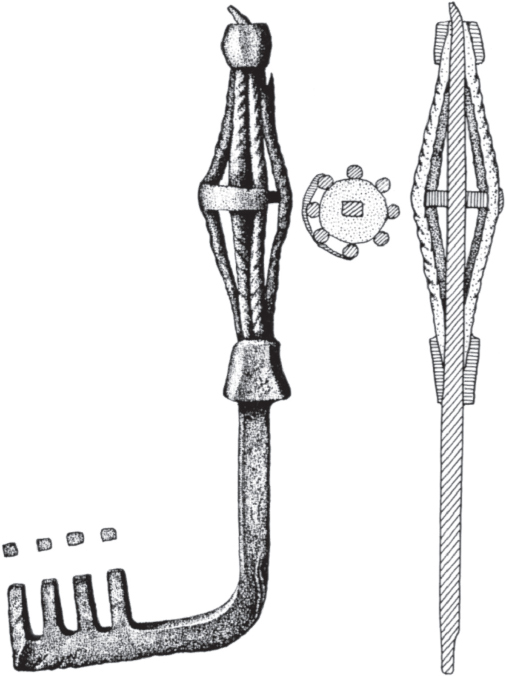

This is not a far-fetched notion, as we already know that her type III objects share several features in common with other artefact types. Looking first at the basket-like ‘handles’, we can note that almost identical constructions are found as the handles of certain types of Viking-Age keys (cf. Aanestad 2004 and Berg 2015 for wider, gendered discussions of these objects). The keys of this type are mostly from Gotland (Fig. 3.79), and examples are known from Rangsarve in Alva parish, Fjäle in Anga, an unknown find-spot in Björke parish, Hanes in Endre, Hallvands in Garda, Hägvards in Hall, Hallegårde in Halla, an unknown find-spot in Hejde parish, Vägome in Lärbro, and an unknown find-spot in Rute parish (Thunmark-Nylén 1998: pl. 207ff; 2000: 33, 40, 60, 140, 223, 311, 347, 377, 495, 607). Another example was found in the Mästermyr tool-chest (Arwidsson & Berg 1983: 9, pl. 19), and a superbly-preserved tenth-or eleventh-century key of this type has been found at the Viking-Age trading centre of Bandlundeviken, also on Gotland (Brandt 2002: 252, 298; Fig. 3.80).

The terminals of the keys would seem to ostensibly support the idea that the openwork device really was the handle of the staffs, and that they were thus held at one end rather as one would grip a sword. However, some of the staffs themselves give the lie to this, for example that from Søreim in Norway, which has an openwork ‘basket’ far too broad for any but the largest hand to grasp. Added to this, an iron rod held in a fire would grow hot, and thus perhaps require insulation to pick up – this would add to the bulk of the ‘handle’, and make it even harder to hold. A good guide to a comfortable grip in the Viking Age, at least for men, can be found in the hilts of swords. When compared, it is immediately clear that several of the staff ‘handles’ exceed these dimensions. When one also considers that women tend to have smaller hands than men, the disparity increases. The Klinta staff is different again, as its ‘basket’ is not only even broader than that from Søreim but is not situated at the end of the object. What then do the ‘handles’ mean? Do the strands of metal forming the ‘basket’ signify anything?

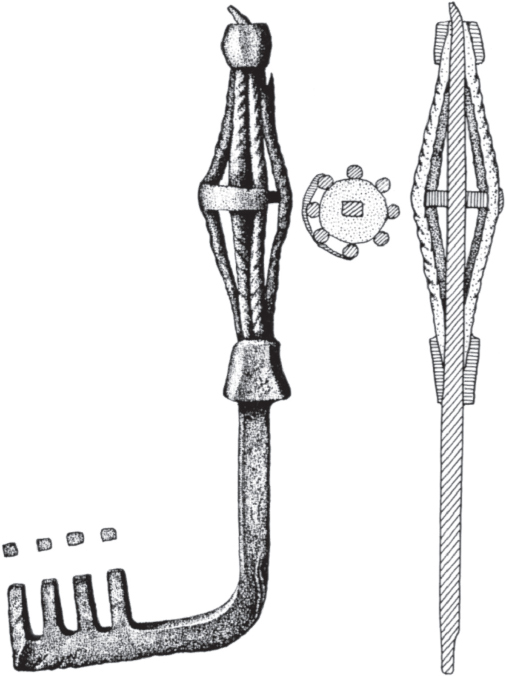

One possible symbolic indicator can be found in an iron object of a similar construction from Gävle in Gästrikland, Sweden, now stored in the National Museum in København (Brøndsted 1936: 196f; Pentz et al. 2009: 224f; Gardeła 2012: 67ff, 2016: 334f; Fig. 3.81). The artefact was found in a male grave with a sword, arrows and jewellery, and is usually interpreted as the shank of a dog-whip. It measures 0.48 m long, with a 0.12 m ‘basket’ at one end, which is topped with a semi-spherical terminal. Below, the ‘basket’ leads into the straight shaft with a gaping animal head, almost identical to those on the Klinta staff and on that from Bj. 760. The shaft terminates in a polyhedral knob and a flat plate on which hangs a ring, with two double spirals and a loop to take the leather thong. Despite similar finds in Finland and Sweden (ibid: 196), there is no certainty that this object has been correctly interpreted, and the ‘rattles’ on the loop could equally imply a magical function (or a combination, as such rattles are common features of horse harness and other objects in the Viking Age, and are found as far away as Ladoga; Brandenburga 1895: pl. IX). The resemblance to the staffs is very striking – the piece from Gävle may even be a staff – and adds yet another confusing dimension to these objects.

Fig. 3.79 One of the iron keys found in the tool-chest from Mästermyr on Gotland, with a handle similar to the ‘basket’ feature on possible staffs of sorcery. The detail of its construction is clearly shown, with bronze disks and terminals, and is identical to that on the ‘handles’ of the staffs (after Arwidsson & Berg 1983: pl. 19; drawing by Janis Cirulis).

Fig. 3.80 The iron key with bronze fittings from Bandlundeviken, Gotland, with a ‘basket’ handle of the same type as the possible staffs of sorcery. The superb preservation gives an idea of how impressive the staffs would originally have looked (after Brandt 2002: 298).

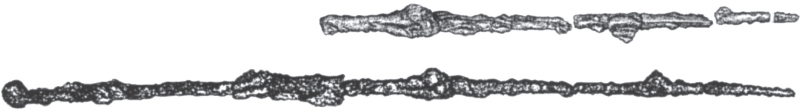

A further parallel for the ‘basket’ construction comes from two remarkable iron chains found in the Oseberg ship burial, in which the links of the chain are each formed like the ‘handle’ of the staffs (Brøgger & Shetelig 1928: 136). Though lacking the central rod which forms the shaft of the staffs, the chain links are each made of four twisted strands of iron with terminal knobs at the top and bottom, fixed by loops to the next link in the chain. It is worth emphasising that on this object the ‘basket’ form clearly has no handle-like functions at all. As we shall see below, the chains were found in a chest which also contained a possible staff of sorcery, though made of wood.

Similar parallels can be found for the polyhedral knobs on the shafts of the staffs, as these are essentially the same as a common form of weight found throughout the Viking world – even the different types of knobs reflect the typologies of weights (see Arbman 1940: pl. 127; Kyhlberg 1980b: 220). In a further connection, these same kinds of polyhedral knobs are occasionally also found on the key handles, as in the example from Rute parish on Gotland.

In my opinion it is these knobs and shaft mounts that also finally dispel the meat spit argument for at least some of Bøgh-Andersen’s type III-M objects. The knobs along the length of the shaft are very substantial, and completely prevent joints of meat from being pushed along the full length of the object. In purely functional terms the staffs therefore cannot be used as meat spits – they simply do not work for this purpose. The only means of using them in food preparation would be to pierce a piece of food on the very point of the shaft and then somehow hold it in a fire, rather in the manner that one toasts marshmallows on a stick.

Those who advocate the meat spit interpretation have also focused on the presence of kitchen implements in the graves, which are claimed as support for the identification of the objects as roasting implements (Petersen was the first to do this, 1951: 428, and Bøgh-Andersen follows this line throughout her 1999 thesis). This argument does not stand up to closer inspection, however, since the kitchen implements of course prove nothing in themselves. They are only of relevance to the staffs if the meat spit interpretation is accepted in advance. This becomes obvious if we consider finds of kitchen utensils in relation to other objects whose function we understand – thus the presence of a frying pan does not ‘prove’ that a sword or a comb was used in the kitchen, but we can only say this because we can immediately recognise the latter objects for what they are, which is not the case with the staffs.

Fig. 3.81 The Viking Age iron ‘whip shank’ from Gävle, Gästrikland, Sweden, with a ‘basket handle’ (photo by Arnold Mikkelsen, National Museum of Denmark).

This is not to say that the staffs do not resemble meat spits, and other objects, for they certainly do. However, in this context it is worth considering our frames of reference in relation to those of the Viking Age – perhaps the keys, weights and meat spits imitated the staffs, rather than vice versa.

To this can be added the variety of embellishments to the ‘basket’ constructions: the loops beneath the model house on the Klinta staff; the perforated attachments to the knobs on the Birka staffs; the spirals and nails on the Jägarbacken and Kilmainham pieces discussed below, like the perforation on the staff from Aska, and so on. Another curious feature of several of the staffs is the presence of one or more rings attached to the ‘handle’. In some of the simpler examples a single ring is present and has been interpreted as a suspension loop for storing the object hanging up, but on other staffs – such as that from Kvåle – there are two rings. The staff from Nordfjord has a ring hanging from each strand of the ‘basket’ construction. It seems unlikely that these are purely for suspension, and on some staffs the rings are decorated further: the Søreim piece, for example, has a Þórr’s hammer attached to it. All these features again imply that the staffs are special objects, and not least that they are even less likely to have been used as meat spits.

As noted in the preface, the bulk of the text in this second edition deliberately preserves the flow of the original. To this end, the subsequent and very exciting body of work by Eldar Heide (2006a–c) is reviewed in chapter 8; suffice to say here that I believe he has resolved the nature and meaning of the ‘handle’ construction beyond reasonable doubt.

Considering all these problems, within Bøgh-Andersen’s type III we can therefore isolate not two but actually four categories:

•staffs without an expanded ‘handle’ construction

•staffs with an expanded ‘handle’ construction

•staffs with an expanded ‘handle’ construction and mounts or knobs on the shaft

•staffs without an expanded ‘handle’ construction but with mounts or knobs on the shaft

In addition, we can note that there is a large variation in the types of ‘handles’, shafts and shaft mounts. In considering these objects as possible staffs of sorcery, we must consider not only the written sources but also the graves in which each individual staff was found. In this light I would suggest that we convert the four above categories into the following three interpretations:

•very probable staff of sorcery: mounts or knobs on the shaft, with or without expanded ‘handle’ construction

•probable staff of sorcery: expanded ‘handle’ construction

•possible staff of sorcery: simple ‘handle’ demarcation

We can review this in the context of the Birka staffs, and ask if we can see them as symbols of high status. Following his argument that the staffs were for measurement, Kyhlberg (1980b: 275) suggests that graves Bj. 760 (660 as he thought), 834 and 845 together build a generational pattern of ‘offi ce-holders’, and that the staff as volumetric measure was a symbol of considerable status – perhaps a female equivalent to male graves with balances. It is unclear how this view might change given that Bj. 760 is a cremation, but perhaps it would simply add a fourth individual to Kyhlberg’s model. As noted above, my interpretation of the burials’ relative chronology differs from Kyhlberg’s, because of his separation of the two individuals in Bj. 834; he assigns the staff to the man, which he sees as the earlier of the two. Following my view of the graves’ dating, there is no ‘generational sequence’, but the idea of the staff as a symbol of great dignity could apply equally well to a sorceress as to a person with control over economic functions. One could also argue that both textile-rules and volumetric measures could be seen as rather mundane objects, of which we might expect to find more examples. Both functions might carry a degree of social status in their performance, but hardly at the level implied by the burial contexts of the objects in question. By contrast, this would not be the case if the staffs were tools of sorcery – all the circumstantial evidence of the graves fits such an interpretation without diffi culty.

Before examining the other Scandinavian staffs, it is worth devoting a few words to the original appearance of the examples from Birka, Klinta and Fyrkat. As always with archaeological finds, the condition of the objects when found makes it hard to visualise how they once looked when new, but in the case of the staffs we should focus especially on the bronze mounts. When first made and polished, these would have gleamed almost like gold, standing out very dramatically against the dark iron of the shafts, especially if the latter had been blacked. An exact reproduction of the Klinta staff has been made for the National Museum of Antiquities in Stockholm, and an examination of this makes very clear the original magnificence of these pieces (see Lamm 2002; Fig. 3.82). This gives a quite different appearance to the ‘handle’ constructions and the knob-mounts on the shafts, and can only increase the likelihood that these were objects of some dignity.

In addition to the examples from Birka, Klinta and Fyrkat, iron staffs of the kinds described above are known from 20 burials in Scandinavia dating to the eighth to tenth centuries, with 12 more from stray finds. It should be noted that for the Norwegian finds especially, Gardeła (2016: 55f) strongly disagrees with my inclusion of some items in my lists of staffs. I refer the reader to his objections for the close detail, but suffi ce to say that in a couple of cases I stand corrected, while in the others I hold to my original view, each explained on an individual basis below. Some of the objects he identifies as staffs, such as those from Gerdrup and Trekroner-Grydehøj, I do not find convincing (see chapter 8), while my catalogue here includes several that he omits altogether. It is interesting – and somehow appropriate for these diffi cult objects – that even after two decades of work, the two scholars who have most closely focussed on the staffs and their analogues do not agree on a final corpus.

Fig. 3.82 A reconstruction of the Klinta staff; note that the shaft of the original was longer (photo Oskar Kullander, Swedish History Museum, Creative Commons).

By my reckoning, three other iron staffs have been found in Iceland and Finland (the Icelandic examples again contested by Gardeła, ibid). In addition to these, five are known from outside Scandinavia, and there are at least four wooden staffs that may belong to this broad category; these are considered separately below (Fig. 3.83). As discussed below, the bulk of the staffs have been catalogued as meat spits by Bøgh-Andersen (1999), working from Petersen’s survey of Viking-Age tools (1951: 421–30).

Fig. 3.83. Find-spots of possible staffs of sorcery from the Viking world (partially based on underlays after Susanne Bøgh-Andersen 1999; originally mapped by Karin Bengtsson 2002; updated by the author, and map created by Daniel Löwenborg, 2018).

•circle = iron staff without shaft mounts

•square = iron staff with shaft mounts

•triangle = wooden staff

•solid symbol = staff with an expanded ‘handle’

•open symbol = staff or shaft without an expanded ‘handle’

•black = burial determined as male

•red = burial determined as female

•yellow = burial without sex determination

•blue = stray find

•green = ritual deposit

Location key

Norway:

1.Arnestad, Sogn og Fjordane

2.Fure, Sogn og Fjordane

3.Gausel, Rogaland

4.Gutdalen Stryn, Sogn og Fjordane

5.Hellebust, Sogn og Fjordane

6.Hilde, Sogn og Fjordane

7.Huseby, Sør-Trøndelag

8.Kaupang, Vestfold

9.Kvåle, Sogn og Fjordane

10. Mindre-Sunde, Sogn og Fjordane

11. Myklebostad, Sogn og Fjordane

12. Nordfjord, Sogn og Fjordane

13. Søreim, Sogn og Fjordane

14. Trå, Hordaland

15. Villa farm, Møre og Rogndal

16. Øvre Høvum, Sogn og Fjordane

17. Hopperstad, Sogn og Fjordane

18. Melhus, Trøndelag

19. Steine, Nordland

20. Tveiten, Buskerud

21. Vatne, Hordaland

22. Vestre Berg, Hedmark

23. Veka, Hordaland

24. Oseberg, Vestfold

Sweden:

25. Birka, Mälaren, Bj. 660.*

26. Birka, Mälaren, Bj. 760

27. Birka, Mälaren, Bj. 834

28. Birka, Mälaren, Bj. 845

29. Gnesta, Södermanland

30. Gävle, Gästrikland

31. Jägarbacken, Närke

32. Klinta, Öland

33. Lilla Ullevi, Uppland

34. Aska, Östergötland 35. Tuna i Hjelsta, Uppland

36. Tuna i Badelunda, Västmanland

Denmark:

37. Fuldby, Sjælland

38. Lejre, Sjælland*

39. Fyrkat, Jylland

40. Ladby, Fyn

41. Fyrkat, Jylland

42. Hemdrup, Jylland

Finland:

43. Pukkila-Isokyrö, Vasa

Iceland:

44. Álaugarey-Nesjahreppur

45. Stærri-Árskógur

Isle of Man:

46. Peel Castle, St. Patrick’s isle

Orkney:

47. Pierowall, Westray

Ireland:

48. Kilmainham, Dublin

Russia:

49. Gnezdovo, Smolensk

50. Lake Zelikovje, Tver

* the expanded ‘handle’ on these objects is assumed by association with similar finds, but not proven.

Not shown: one unprovenanced iron staff with expanded ‘handle’ construction from Norway.

We can review them here by type and country. All the following entries describe burials with staffs of the stated kind, with full descriptions in cases where the graves have been published (again augmented with reference to the new catalogue in Gardeła 2016). If no reports were made (i.e. for entries below that include no information other than dating, location and the sex of the burial), for more information the reader is referred to the nineteenth-century accession registers of the relevant museums, references for which are given below.

These objects have been found as follows:

•Female burials (note: all sex determinations have been claimed by the respective excavators solely through artefactual association, and are thus to be regarded as highly provisional)

○Fure – Askvoll sogn, Sogn og Fjordane

▪A square-section iron staff, some 0.84 m long, with a ‘handle’ construction. Found in an unmarked chamber grave with items of conventionally female jewellery and household equipment. Dated before 800 (ÅFNF 1893: 148; Petersen 1951: 426ff; Bøgh-Andersen 1999: 47f; Gardeła 2012: 96ff, 2016: 290f).

○Huseby – Børseskogn sogn, Sør-Trøndelag

▪Damaged iron staff, 1.04 m in length, probably originally longer; second half of the ninth century (TVSS 1908/14: 13; Petersen 1951: 426ff; Bøgh-Andersen 1999: 47f)

○Trå – Granvin sogn, Hordaland

▪A mound inhumation, presumed to be female on the basis of numerous items of jewellery. The grave included a rich array of textile-working equipment and kitchen implements – one of the reasons why the staff has earlier been interpreted as a meat spit. Only the lowest terminal of the ‘handle’ is preserved, but by comparison with more complete examples the staff appears to have had a ‘basket’ construction (Gardeła disagrees, 2016: 55f, 316). It has recently been argued that the burial is that of a female cult leader, possibly a gyðja – an intepretation that would fit well with the presence of the staff (Kaland 2006; cf. Gardeła 2016: 60–3). The surviving staff fragment measures 0.88 m in length and was originally longer; first half of the tenth century (BMÅ 1913/14: 45; Petersen 1951: 426ff; Bøgh-Andersen 1999: 47f; Gardeła 2016: 316f).

○Arnestad – Gjemmestad sogn, Sogn og Fjordane

▪A cremation under a layer of birch bark and a mound, the human remains largely interred in an iron cauldron. The remains were artefactually sexed as female due to the presence of oval brooches, textile-working equipment and cooking implements. Dated to the tenth century (BMÅ 1924–25/2: 37; Petersen 1951: 426ff; Bøgh-Andersen 1999: 47f; Gardeła 2012: 78ff, 2016: 288f).

○Hilde – Innvik sogn, Sogn og Fjordane

▪A cremation burial under a mound, with weaving equipment and an array of household items suggesting an artefactual female sex determination. The grave also included a complex amulet with nine Þórr’s hammers. An important burial for the interpretation of the staffs, because in addition to the 0.95 m-long ‘basket’ type noted here the grave also included a true meat spit formed as a fork (Bøgh-Andersen’s type I). Tools are rarely duplicated in Viking-Age graves, and this provides further indication that the ‘basket’ staffs are not meat spits; tenth century (BMÅ 1901/12: 25; Petersen 1951: 426ff; Bøgh-Andersen 1999: 47f; Gardeła 2012: 90ff, 2016: 298f).

○Kvåle – Stedie sogn, Sogn og Fjordane

▪A cremation burial under a stone cairn, the latter also containing burnt bone. Household items, textile-working equipment and ‘female’ jewellery provide an artefactual sex determination. A complete, slightly bent iron staff with outstanding preservation, c.0.8 m long, with two possible suspension rings above the ‘basket’, and indentations on each side of the knobs that adorn it; the purpose of these is not known; tenth century (ÅFNF 1880: 241f; Petersen 1951: 426ff; Bøgh-Andersen 1999: 47f; Gardeła 2012: 75ff, 2016: 302f).

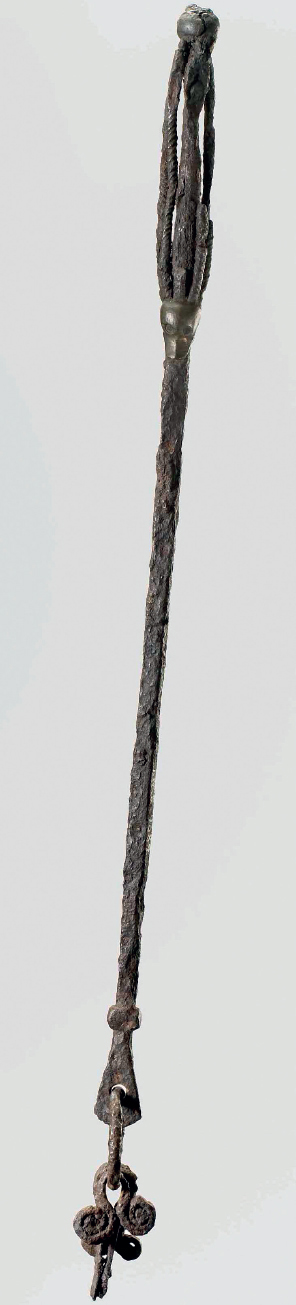

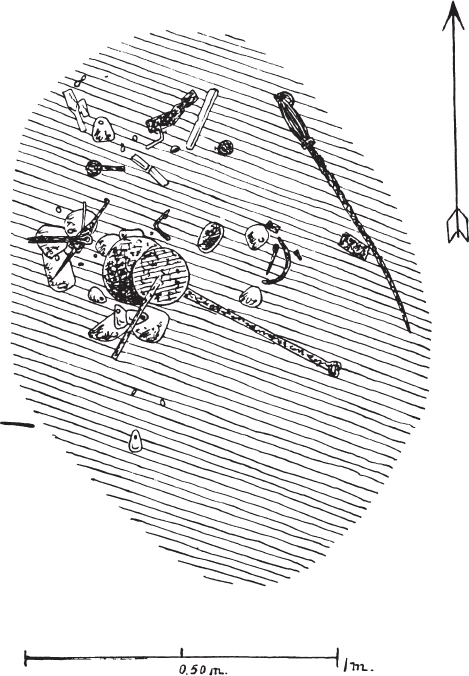

○Myklebostad – Eid sogn, Sogn og Fjordane (Figs 3.84, 3.85)

▪A cremation under a mound, with the artefactually-sexed remains of a woman who had been burnt together with a dog and a chicken in a small boat, the ashes of which had been collected from the pyre and transported to the site of the burial. The grave-goods included textile-working implements, cooking accessories, jewellery and beads, and the remains of at least one wooden box with iron mounts; a single bronze ring may have been meant for the big toe, the only comparable example to the toe-rings from Fyrkat 4. A small dog and a chicken had also been present on the pyre. The staff found was well-preserved, 0.88 m in length and 2 cm thick with a square cross-section. The ‘basket’ construction had two polyhedral terminals, and a ring at one end. Most of the grave-goods were piled randomly in the northwest part of the cremation layer, and the excavator noted how the staff had been placed apart from them in the northeast part of the ashes. A male warrior grave had been cut into the upper levels of the mound after the main interment, and was probably a later, secondary burial. The woman’s grave can be dated to the tenth century (BMÅ 1903/3: 21; Shetelig 1905, 1912: 188–94; Petersen 1951: 426ff; Bøgh-Andersen 1999: 47f; Gardeła 2012: 81ff, 2016: 306f).

Fig. 3.84 Plan of the burial in mound 4 at Myklebostad, Eid sogn, Sogn and Fjordane (after Shetelig 1912: 191).

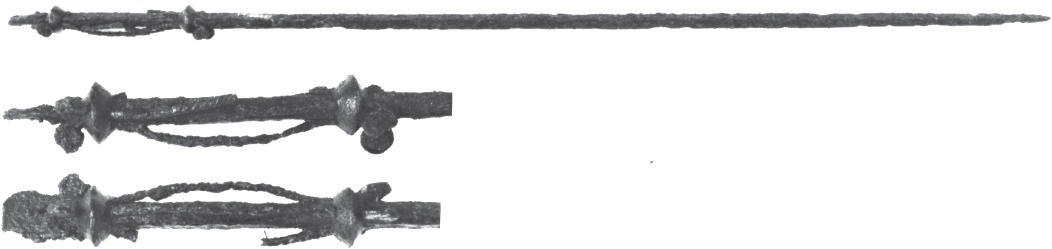

Fig. 3.85 The staff from the burial in mound 4 at Myklebostad, Eid sogn, Sogn and Fjordane (after Shetelig 1912: 193).

○Nordfjord – Sogn og Fjordane

▪Tenth-century iron staff, with an iron ring hanging from the terminal end of each strand in the ‘basket’ construction. (BMÅ 1904/6: 26; Petersen 1951: 426ff; Bøgh-Andersen 1999: 47f).

○ Øvre Høvum – Nes sogn, Sogn og Fjordane

▪A flat cremation, dated to the tenth century and artefactually sexed as female due to the presence of textile-working equipment and household items. The staff is 0.91 m long, square in section and slightly bent (BMT 1919: 44; Petersen 1951: 426ff; Bøgh-Andersen 1999: 47f; Gardeła 2012: 93ff, 2016: 310f).

○Villa Farm – Vestnes sogn, Møre og Rogndal

▪Found in an 8 m-diameter mound on a sandbank some 22 m from the sea, in connection with a cremation urn, the staff is exceptionally large at 0.9 m long, with its tip deliberately bent. The burial also contained significant numbers of high-status objects, presumed to be associated with women: a pair of fine-quality oval brooches, beads including silver examples, an ornamented comb, a whalebone plaque and weaving batten, a sickle and shears of iron, m fragments of a whetstone, a wooden box, and a ceramic urn. The mound was excavated in 1894 and not well recorded, but it seems to have included a harnessed horse and quite possibly the remains of a cremated boat (Villa 1894; Brunning 2016; Gardeła 2016: 346 records this item as unprovenanced, but I am grateful to Barry Ager and Sue Brunning for their pers.comm. with further details on this burial).

•Male burials (note: all sex determinations have been claimed by the respective excavators solely through artefactual association, and are thus to be regarded as highly provisional)

○Hellebust – Vik sogn, Sogn and Fjordane

▪A poorly documented mound burial, though whether inhumation or cremation is unknown. The grave contained a full array of weapons, together with horse quipment, and was thus provisionally sexed as male. Only the lowest terminal of the ‘handle’ is preserved, but it is unclear whether an ‘expanded’ frame was present (Gardeła thinks not, and suggests that what I see as the lower part of a ‘handle’ is instead a mount on the shaft – 2016: 55f, 296). I retain its classification here, but it must be reagrded as very tentative; eighth century (Nicolaysen 1862– 66: 487; Petersen 1951: 426ff; Bøgh-Andersen 1999: 47f; Gardeła 2012: 102ff, 2016: 296f).

○Mindre-Sunde – Nedstryn sogn, Sogn and Fjordane

▪A stone-lined flat ‘grave’ construction, without any preserved human remains; an abundance of weapons suggests that the deceased was male. The staff is preserved to a length of 0.83 m and is in poor condition. My own examinations suggest that a ‘handle’ was present, though now badly damaged; Gardeła again disgrees (2016: 55f, 304), but as above I provisionally retain its original classification. Eighth century? (ÅFNF 1887: 119; Petersen 1951: 426ff; Bøgh-Andersen 1999: 47f; Gardeła 2012: 99ff, 2016: 304f).

•Stray finds, probably from burials

○Søreim – Dael sogn, Sogn and Fjordane (Figs 3.86)

▪Iron staff with a very broad four-strand ‘basket’, linked by a thin horizontal plate at the centre of the ‘handle’. The latter terminates in a ring on which is threaded a Þórr’s hammer. The staff is 0.96 m long and can be dated to the Viking Age without further precision (ÅFNF 1872: 68; Petersen 1951: 426ff; Bøgh-Andersen 1999: 47f; Gardeła 2012: 84ff, 2016: 314f).

○Gutdalen Stryn – Sogn og Fjordane

▪A very long staff, c.1 m, located by Gardeła in Bergen Museum. Bent almost double, and with an elaborate ‘handle’ of 6 rods to which are affixed 5 rings – a truly exceptional example, but unfortunately without context (Gardeła 2012: 87ff, 2016: 294f).

○Norway – unprovenanced

▪A very crudely made iron staff, found bent round in a curve and with the point missing. Its present length is approximately 0.35 m, with a square-section shaft up to 1.5 cm thick. The ‘handle’ is made from four strands of iron, bowed around the central shaft and joined at both ends by a disk of iron approximately 2.5 cm in diameter and 1 cm thick. The disk nearest the terminal of the ‘handle’ also has a thin band of iron wound tightly across its width at one point. From this disk also projects a flattened loop of iron, with an eye perhaps 3 mm in diameter. The staff is of undetermined Viking-Age date (Undset 1878: 81; Petersen 1951: 426ff; Bøgh-Andersen 1999: 47f; Gardeła 2016: 345ff).

Fig. 3.86 The staff from Søreim, Dael sogn, Sogn and Fjordane (after Petersen 1951: 423).

Sweden

•Female burial (note: sex determination has been claimed by the excavator solely through artefactual association, and is thus to be regarded as highly provisional)

○Jägarbacken – Ånste sn, Närke (Figs 3.87, 3.88)

▪Grave 15 from the Jägarbacken cemetery, in which the cremated remains of a woman (suggested by the presence of an extensive jewellery set and dress accessories) had been buried in two pottery vessels placed on the ashes of the pyre. The deceased had been burnt with a full complement of brooches, beads and personal items such as a comb and shears, and it seems that a horse was also cremated together with a set of draught harness. The grave also contained an iron staff, which was 0.81 m long with a 0.15 m ‘basket’ and two ornamented bronze terminal knobs. The latter were augmented by small bronze spirals attached so as to stand proud of the shaft, and the end of the ‘handle’ had been hammered into an oval plate through which a nail had been fixed; the purpose of these embellishments is unknown. The staff had not been burnt on the pyre, but had instead been thrust vertically into the ashes surrounding the woman’s bones; around the staff two unburnt oval brooches had been placed. The whole deposit, including the staff and brooches, was then covered by an earthen mound. The grave can be dated to the tenth century (Hanson 1983: 8, 24; Bøgh-Andersen 1999: 82f; Graner 2007: 52–61; Gardeła 2012: 54ff, 2016: 338–41).

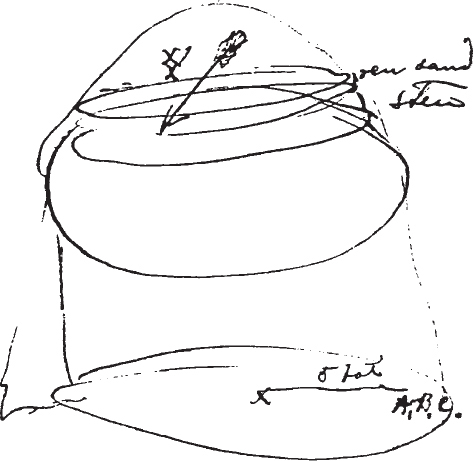

Fig. 3.87 The iron staff from the Jägarbacken cemetery in Närke, with details of its ‘handle’. Note the spirals around the terminal knobs, and the flattened plate at the end (after Hanson 1983: 24).

Fig. 3.88 Contemporary sketch of the cremation deposit of grave 15 at the Jägarbacken cemetery in Närke, investigated in 1896 by Emil Ekhoff. The layer marked ren sand, sten (‘pure sand, stone’) covered the cremation, and the arrow-like mark above indicates how the iron staff was standing vertically in it, with the mound built up on top (after Hanson 1983: 8).

Fig. 3.89 Detail of the ‘handle’ on the staff from Gnesta in Södermanland (after Bøgh-Andersen 1999: 83; drawing by Håkan Dahl, used by kind permission).

•Stray finds and settlement deposits

○Gnesta – Södermanland (Fig. 3.89)

▪Found in 1892 somewhere in the vicinity of the railway station, the Gnesta staff was 0.66 m long, with a 0.15 cm ‘basket handle’ incorporating particularly richly decorated bronze knobs at each end. Viking Age (Bøgh-Andersen 1999: 83f; Gardeła 2012: 58ff, 2016: 336f).

○Lilla Ullevi, Bro sn, Uppland

▪Excavated from deposits associated with a ritual structure, interpreted as a horgr offering platform, this fragmentary object appears as the expanded ‘handle’ section of a staff. Four twisted iron rods are preserved, with a single mount holding them together at one end; the rest of the object is broken off. There is a possibility that this is the remains of a key, of the kind reviewed above and with a specific parallel in a similar context from Gamla Uppsala (Beronius Jörpeland et al. 2017: 198–201; Eriksson 2018: 283f). However, its proximity to what the excavators have tentatively identified as a seiðhjallr merits its inclusion here as a tentative staff of sorcery (Bäck et al. 2008: 53f; Gardeła 2016: 345ff). A second fragment of iron rod with an unusual but plain ‘handle’-like terminal resembling that from Fyrkat, found in a different and much later context at the same site, does not seem convincing to me (Bäck et al. 2008: 54; Gardeła 2016: 345ff).

•Burial of indeterminate sex?

○Fuldby – Bjernede sn, Sorø amt (Fig. 3.90)

▪Found in 1868, probably in a heavily disturbed grave under a large stone, originally thought to be the burial of a man due to the find of a stirrup (now lost) but it is also likely that the finds represent the disturbed remains of several burials; there is therefore no basis on which to make even a preliminary sex determination of the presumed grave. The staff has a ‘basket handle’ with twisted iron rods in the cage, with corroded terminal mounts of which at least one seems to represent a beast’s head. Tenth century (Brøndsted 1936: 196f; Bøgh-Andersen 1999: 52; Pentz et al. 2009: 224f; Gardeła 2012: 31f, 2016: 272f).

Finland

•Burial of indeterminate sex

○Pukkila-Isokyrö, Vasa län (Fig. 3.91)

▪A richly-furnished boat cremation, redeposited in a pit on a flat-ground cemetery. New analysis of the bones suggests that the boat contained at least two individuals of indeterminate sex, one aged 10–24 and other 18–44. Finds of helmet, shield, sword and scabbard, spear, arrows, axe, scramasax, knife, toilet implements, cooking implements and agricultural tools. Conventionally the artefact assemblage might be sexed as male, but this is highly uncertain and the burial contained at least two people. The grave has been preliminarily dated to the eighth century (contra Gardeła, 2016: 345). The staff is broken a short distance below the ‘basket’ feature and has been consistently interpreted as a meat spit; its solid square section suggests that it is a staff, and not a broken-off key (Hackman 1938: 154f; Kivikoski 1973: 88, taf. 71; Bøgh-Andersen 1999: 47f; Gardeła 2016: 345ff; see also discussions in Wessman 2010).

These objects have been found as follows:

Norway

•Female burials (note: all sex determinations have been claimed by the respective excavators solely through artefactual association, and are thus to be regarded as highly provisional)

○Hopperstad – Vik sogn, Sogn and Fjordane (Fig. 3.92)

▪A probable cremation in a boat, though poorly recorded. A finely-wrought staff with a decorated bronze ‘handle’, accompanying a woman (artefactually sexed through jewellery and household items). The burial was exceptionally rich, and dated c.900. It included western European bronze vessels and glass, and bronze-mounted buckets (ÅFNF 1887: 125; Petersen 1951: 426ff; Bøgh-Andersen 1999: 47f; Sørheim 2011; Gardeła 2012: 117f, 2016: 75f, 300f).

Fig. 3.90 The staff from Fuldby, Bjernede on Sjælland (photo by Arnold Mikkelsen, National Museum of Denmark).

Fig. 3.91 The staff from Pukkila-Isokyrö, Vasa län, Finland (after Bøgh-Andersen 1999: 52; drawing by Håkan Dahl, used by kind permission).

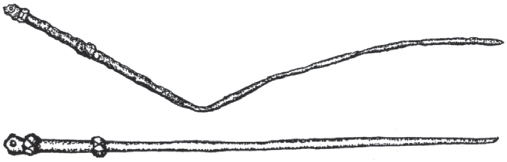

Fig. 3.92 The iron staff with bronze ‘handle’ from Hopperstad, Viks sogn, Sogn and Fjordane (after Petersen 1951: 423).

○Veka – Vangen sogn, Hordaland (Figs 3.93–3.96)

▪A complex, artefactually-sexed female inhumation, constructed in several distinct phases. On a southwest-facing slope above a river and overlooking a ford, a gently trapezoidal grave measuring 2.7 × 1 m had been cut 0.45 m deep into the sandy sub-soil. The grave had then been completely lined and floored with wooden planks. The resulting ‘box’ had then been lined with bark which had in turn been partly covered by textiles (perhaps a blanket?), on which the dead woman had been laid with her grave-goods. After the interment had been completed, the grave was sealed with a wooden lid, also lined with bark. This was then covered by large stone slabs piled irregularly over the grave. Above this had been raised a stone cairn, and finally a covering mound of earth 30 m in diameter, carefully built into the contour of the slope which had been dug away on the upper side to make the barrow a more imposing monument. The woman had been buried on her side, with a rich collection of jewellery – two oval brooches of type P51 B1, a bronze brooch, several necklaces with more than 100 beads in total, and arm-rings. Round her neck lay 16 beads individually strung on thin silver rings – either a remarkable necklace, or perhaps sewn onto her clothes. An Anglo-Saxon coin of Offa, already very old when buried in the grave, had been laid in the coffin behind her head. The Veka woman also had with her a sickle, comb, knife, and items for sewing and textile-working, several of them collected in a large box which had been placed at the foot of the grave. Aligned with the centre of the grave with its ‘handle’ at a level with the woman’s waist, lay a 0.74 m iron staff with polyhedral knobs. The two armrings were found on top of the ‘handle’, implying that the woman had been buried with her hands folded over the staff. The grave dates from the tenth century, and I here employ Shetelig’s early spelling of the place-name, an alternative to Veke (BMÅ 1909/14: 25; Shetelig 1912: 206–10; Petersen 1951: 426ff; Bøgh-Andersen 1999: 47f; Gardeła 2012: 108f, 2016: 320f).

○Vatne – Seim sogn, Hordaland

▪A cremation under a low mound, artefactually sexed as female due to the presence of textile-working implements and jewellery. Only the lowest terminal of the ‘handle’ is preserved, and the shaft is noticeably bent. In the first edition I classified this as having a fragmentary ‘expanded handle’ construction, but following Gardeła’s observations (2016: 55f) I agree with him that this was probably not present and the staff has therefore been reclassified here; tenth century (ÅFNF 1879: 242; Petersen 1951: 426ff; Bøgh-Andersen 1999: 47f; Gardeła 2012: 111ff, 2016: 318f).

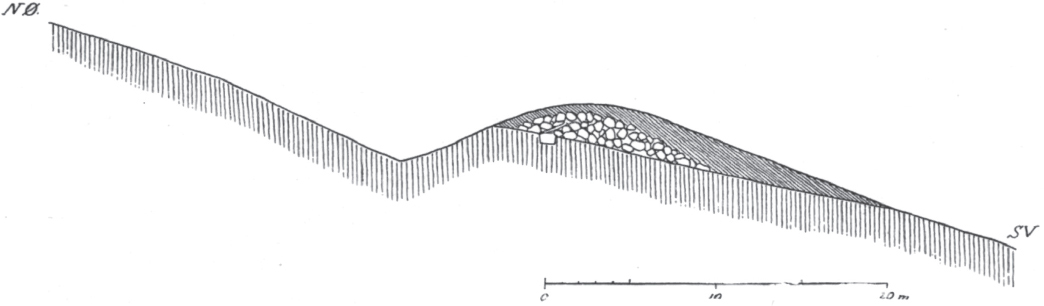

Fig. 3.93 A northeast–southwest section through the grave from Veka in Vangen sogn, Hordaland, showing the location of the burial mound on a gentle slope; the inner grave construction can be clearly seen (after Shetelig 1912: 207).

Fig. 3.94 Plan of the inhumation at Veka, Vangen sogn, Hordaland (after Shetelig 1912: 207).

•Male burial (note: sex determination has been claimed by the excavator solely through artefactual association, and is thus to be regarded as highly provisional)

○V. Berg – Løten sogn, Hedmark

▪A poorly documented burial, producing a damaged staff, perhaps with a suspension ring, from the first half of the tenth century (ÅFNF 1887: 85; Petersen 1951: 426ff; Bøgh-Andersen 1999: 47f).

•Double burial (note: sex determination has been claimed by the excavator solely through artefactual association, and is thus to be regarded as highly provisional)

○Melhus – northern Trøndelag

▪A high-status boat burial under a mound, set within a small barrow cemetery. No human remains were preserved, but from the artefactual assemblage it has been suggested that it originally contained a man and a woman. The grave included a full set of weaponry, a rare insular reliquary, a range of expensive jewellery, and a half-metre fragment of a square-section iron rod. Once seen as a roasting spit, following the arguments of this book’s first edition the object has recently been reinterpreted as a staff, and the Melhus woman is now viewed as a ‘mistress of the cult’ with her ‘ritual tools’ (Petersen 1907; Heen-Pettersen & Murray 2018: 73ff).

•Stray finds, probably from burials

○Steine – Bø sogn, Nordland

▪A finely-made staff with biconical knobs on the

‘handle’; unspecified Viking-Age date (Nicolaissen 1903: 11; Petersen 1951: 426ff; Bøgh-Andersen 1999: 47f).

○Tveiten – Veggli sogn, Buskerud

▪A well-preserved, complete staff 0.82 m long, with a 16.5 cm ‘handle’ demarcated by two knobs with quadriform projecting points. From the terminal knob projects a flattened plate of iron with a pierced hole, in which hangs an undecorated iron ring 6.5 cm in diameter. The staff is of indeterminate Viking-Age date (Undset 1888: 29; Petersen 1951: 426ff; Bøgh-Andersen 1999: 47f).

Fig. 3.95 Reconstruction of the inhumation at Veka, Vangen sogn, Hordaland as it may have appeared when the burial was sealed (drawing by Þórhallur Þráinsson).

Fig. 3.96 The staff from the inhumation at Veka, Vangen sogn, Hordaland (after Shetelig 1912: 210).

Sweden

•Female burial (note: sex determination has been claimed by the excavator solely through artefactual association, and is thus to be regarded as highly provisional)

○Aska – Hagebyhöga sn, Östergötland (Fig. 3.97)

▪The iron staff measured 0.72 m in length, its ‘handle’ being effectively an extension of the shaft, though somewhat thicker and delineated by two polyhedral iron knobs at the top and bottom. The end of the staff above the ‘handle’ terminates in a flattened iron plate, with a single perforation. The burial can be dated to the ninth–tenth century, and has been discussed in detail above (Arne 1932b: 67–82; Bøgh-Andersen 1999: 80f; Larsson 2010: 115f; Gardeła 2012: 64ff, 2016: 322f; Andersson 2018: 168–73).

•Male burial (note: sex determination has been claimed by the excavator solely through artefactual association, and is thus to be regarded as highly provisional)

○Tuna – Hjelsta sn, Uppland

▪An assemblage recorded in 1823 as coming from a disturbed burial in Tuna, “Giresta sn.”, Uppland. There is no place of that name in the parish, but it is in fact located in neighbouring Hjelsta, on a spit of land extending into Giresta parish, hence the confusion. The Tuna site includes two distinct Viking-Age mound cemeteries, and it is unsure from which of them the finds derive. The iron staff is in two fragments, one 0.18 m long, the other only 0.04 m; both appear to be fragments of the shaft (nothing remains of any ‘handle’), and each fragment includes a rounded mount of bronze very similar to those on the Fyrkat staff. Other finds in the assemblage include a sword and spear, a richly decorated pennanular brooch of high quality, a key, a single weight, a ceramic pot, and various buckles and harness. Of close interest is the presence of a decorated bronze vessel of Eastern type, similar to those from Aska and Klinta – thus the third such combination of a staff and a container of this kind. The assemblage can be dated to the tenth century (Odencrants 1934: 148f).

Fig. 3.97 The staff from Aska in Hagebyhöga, Östergötland, as found and reconstructed (after Bøgh-Andersen 1999: 81; drawing by Håkan Dahl).

Fig. 3.98 Two views of the fragmentary staff from Álaugarey in Austur-Skafteafellssysla, Iceland, showing the object when found and as preserved today; the projections on the shaft seem to be corrosion products (after Bøgh-Andersen 1999: 55; drawing by Håkan Dahl, used by kind permission).

Denmark

•Male burial (note: sex determination has been claimed by the excavator solely through artefactual association, and is thus to be regarded as highly provisional)

○Ladby – Fyn

▪Found amidships in one of Scandinavia’s most famous ship burials, this is a fragmentary object of iron rods plated with silver and gold, together with a shaft mount and an object resembling a berlock, decorated in the Borre style. As early as 1957 parallels were drawn with what were then considered to be meat spits or whips, and – tentatively – it is possible that this object may have been part of a staff, not least in view of contextual parallels with Oseberg. The ship grave is from the tenth century, though the object itself may be older (Thorvildsen 1957: 74–7; Sørensen 2001: 93f; Gardeła 2012: 126f, 2016: 276f).

Iceland

Two staffs are also known from Iceland, both from burials of the ninth to tenth centuries, one female and one probably male. Gardeła (2016: 56f) is sceptical to both examples, but I am not convinced by his objections to their identification as staffs; however, I agree that they do not have clear ‘handle’ constructions:

•Female burial

○Álaugarey – Nesjahreppur, Austur-Skaftafellssysla (Fig. 3.98)

▪A richly-furnished grave under a low mound, with a female skeleton accompanied by two oval brooches, an armring, comb, knife, shears and a box. No information was recorded about the disposition of the grave-goods. The staff was 0.78 m long, though it is now much corroded and fragmented into six pieces; to judge from drawings of the object when first excavated it was probably no more than 0.8 m long originally, and was thus complete when found. One terminus is curved round in a loop, a unique feature, while what appear to be knob-mounts on the shaft are actually build-ups of corrosion (no X-rays were made before the staff disintegrated into six pieces). Ninth to tenth century (Shetelig 1937: 210; Eldjárn 1956: 185f; Bøgh-Andersen 1999: 55f; Eldjárn & Adolf Friðriksson 2016: 240f, 617; Gardeła 2012: 132f, 2016: 280f).

•Male (?) burial

○Stærri-Árskógur – Árskógshreppur

▪A probable man’s grave on the west bank of Eyjafjörður, the corpse buried in a sitting position. The grave also contained a knife, with the burial of a horse 5 m away to the north. Only 0.2 m of the staff is preserved, but it does not seem to have had the ‘basket’ construction; on close inspection, the object could not have been used for roasting as the shaft has a rounded end that would not permit the threading of meat. Ninth–tenth century (Eldjárn 1956: 131f; Bøgh-Andersen 1999: 56; Eldjárn & Adolf Friðriksson 2000: 171, 605; Gardeła 2012: 134f, 2016: 282f).

In addition to the staffs from Scandinavia and the North described above, four (possibly five) others have been found in Viking-Age Scandinavian contexts in other countries.

One of these has been described above, in conjunction with the female inhumation at Peel Castle, St. Patrick’s Isle, in the Isle of Man. A second example can also be tentatively identified from the British Isles, from the site of Pierowall on Westray, Orkney (Thorsteinsson 1968; Graham-Campbell & Batey 1998: 129–34; I am indebted to Steven Harrison for bringing this to my attention). In the course of the nineteenth century at least 17 Viking-Age burials were revealed by coastal erosion at the site, but only sketchily recorded; the first systematic analysis of what remained was undertaken as late as the 1960s. One of the burials, Grave 2, was found in 1839 and is remarkable in that it is (as far as I am aware) the only furnished insular Scandinavian interment in which the body was placed face-down. The corpse was wearing two oval brooches, and a ringed pin was also found, suggesting that the person was female. Along the right side of the body lay a long iron implement, which Graham-Campbell & Batey (1998: 131) suggest may have been a knife or a weaving sword. The object is unfortunately now lost, but the description and unusual practice of prone burial suggest to me a serious possibility that this may have been a staff. We can do little more with this find, but the presence of a sorceress in the Northern Isles would in no way be divergent from the wider pattern that we have seen in the distribution of such burials.

Fig. 3.99 The fragmentary iron staff from the Kilmainham cemetery outside Dublin, Ireland, probably from a woman’s grave of the mid-ninth century (after Bøe 1940: 97).

Another grave of this kind outside Scandinavia is from Ireland, where a fragmentary iron staff has been found outside Dublin (Bøe 1940: 97; Fig. 3.99). Long thought to be of unknown provenance, a confident attribution to the Kilmainham cemetery has now been made (Harrison 2001: 68; Harrison & Ó Floinn 2014: 206f). The staff can probably be dated to the mid-ninth century on the basis of the other finds from this cemetery, which seems to have been exclusively associated with the longphort established there in 841. The object is now 0.38 m long, but was once much longer (Gardeła 2016: 284–7). It is of the ‘basket’ type, though all but the ends of the rods have corroded away. A single knob survives, which appears to have been shaped as a flattened sphere with rows of linear ornament; this too is a common form among Viking-Age weights. Only the beginning of the main shaft is present, and this seems to taper in a manner reminiscent of the Fyrkat staff, and it also bears comparison with the example from Jägarbacken. Little further can be added on this piece, except to note that these objects – and presumably their bearers – also found their way to the Scandinavian ventures in Ireland at a very early date. This would provide an interesting link with the description of a possible seiðr performance in the Cogadh Gaedhel re Gallaibh, discussed in chapter 2. If this is the staff of a volva or similar, then this has implications for the nature of these early Viking expeditions to Ireland.

The third and fourth staffs are both spectacular finds from Russia which fall into the same category as those from Birka, Klinta and Fyrkat in that they also have knob-mounts on the shaft, and are thus among the objects that can most securely be interpreted as staffs of sorcery.

One was excavated in 1987 from mound Lb-1, a tenth-century burial from the Lesnaja cemetery at Gnezdovo, the precursor to Smolensk at the start of the Dniepr passage (Fig. 3.100). On the basis of an equal-armed brooch from the same grave, it has been artefactually sexed as female, though of course this is uncertain (Egorov 1996: 59, 64; Duczko 2004: 173; Gardeła 2016: 345ff). The staff was 0.43 m long when found, but the point is missing and the object was presumably once longer. Apart from the missing point, the staff is in excellent condition and particularly interesting in that it clearly lacks the ‘basket handle’ construction – unlike all the others with shaft mounts. The staff is of square section, made of iron and at one end a hand’s length of shaft is bounded by two cast bronze polyhedral mounts, apparently decorated with small notched markings in diamond patterns. A short way down the shaft below the ‘grip’ is a third bronze mount of the same kind. Above the ‘grip’ the shaft continues for a short distance and then splays out to a flat plate that forms the terminal of the staff. Interestingly, and apparently without knowledge of the Scandinavian parallels, the excavators interpreted this object as a shezl, ‘staff’.

The other Russian example comes from a grave excavated in 1961 on the north shore of Lake Zelikovje in the Tver oblast. Little information is available but the burial contains a single silver oval brooch (Petersen type P-52) of the tenth century and thus could arguably be female. The square-section staff is preserved in two fragments, one of which has two polyhedral bronze mounts decorated with symbols and dot-punched ornament (Eremeev 2007: 252f; Gardeła 2016: 346f).

Fig. 3.100 The iron staff from Gnezdovo, near Smolensk in northwest Russia (after Egorov 1996: 64).

In addition to the staffs of iron and bronze, there are also a small number of wooden staffs that have been discovered in Viking-Age Scandinavian contexts, mostly from funerary deposits (see also Jonsson 2007 for numerous other examples continuing into Christian times).

One of these, the long staff in grave 4 at Fyrkat, has been mentioned above. Its length was uncertain as it survived only as a cavity in the corrosion products on the iron meat spit, next to which it had been lying (Roesdahl 1977a: 91). The staff was about the thickness of a finger, and thus unlikely to have been a walking stick. We can say little more about it except to note the emphasis on thin flexibility among some of the staffs described in the written sources, such as the gambanteinn. If the object did have some magical connotations, then the Fyrkat grave is the only one so far known to contain two possible staffs of sorcery – the other being the metal rod with shaft mounts discussed above.

Fig. 3.101 The wooden staff from the Oseberg ship burial (after Ingstad 1992b: 240).

The most spectacular of the wooden staffs from Scandinavian graves is that from the Oseberg ship burial (Brøgger & Shetelig 1928: 270f; Ingstad 1992b: 240; Gardeła 2012: 120ff, 2016: 66–73, 104f, 308f; Fig. 3.101). Its deposition is interesting as it was found in the lower oak chest in the grave chamber, a 1.09 m-long iron-studded box with animal-head clasps that is paralleled only by the chest in Birka grave Bj. 845, which is discussed above as another possible volva burial. In view of the nature of these graves, the placement of the Oseberg staff in such a chest is unlikely to be coincidental. Another curious feature is that the chest also contained the two ornately-wrought iron chains mentioned above, the links of which closely resemble the ‘basket’ constructions on the metal staffs (Brøgger & Shetelig 1928: 136).

Unfortunately, due to the plundering of the grave chamber in antiquity, more details of its exact disposition are unknown. In the context of the deliberate disturbance of the grave, it is interesting that those who broke into the chamber chose not to open the chest containing the possible equipment of sorcery. The chest is discussed by Brøgger & Shetelig (1928: 118–21) while its opening in situ and the layout of the contents is described by Brøgger, Falk & Shetelig (1917: 38–41). The relation of this box’s contents to the scenes on the tapestries from the Oseberg grave has been reviewed above.

The Oseberg staff is 1.07 m long and formed as a hollow tube, made in two half-sections of birch originally fastened together with twine or some other organic substance that has now decayed. Six 1 cm-wide indentations encircle the shaft of the staff at regular intervals along its length, and the binding material was probably wound around it at these points. The object is finely polished and planed to give a somewhat faceted appearance, but is otherwise undecorated. Ingstad (1995: 142f) argues that the staff represents a variety of symbols, including the reed of fertility and a kind of state sceptre which has resonances with later medieval examples, and also the staffs of the volur. The first two of these associations are very difficult to support, I feel, but the idea of the Oseberg cane as a symbol of sorcery fits well with the rest of the grave. Again, this may represent one of the staff forms mentioned in the written sources, and given the status of the Oseberg grave, presumably one of the most powerful of these. It also has some parallels with a wooden object bound with metal ribbon and found in Becan Bog, Co. Mayo, Ireland. This has been interpreted as a reed instrument, and dated by radiocarbon to the eighth century (O’Dwyer 2002).

Another wooden object in a female inhumation grave, from Os in western Norway, has also been claimed as the staff of a volva (Hjørungdal 1989: 102f; 1990). The burial dates from the late Migration period, which Hjørungdal takes as an indication that such sorceresses can be traced far back into the Scandinavian Iron Age. This is a problematic assertion, however, as is the identification of the grave as that of a volva. Firstly, the ‘staff’ is actually more like a small post rather than a portable object. Shetelig (1912: 134) writes that it was square in section, 2 m long and 9 cm in diameter. While it may have been a tool of sorcery, there is nothing to actually suggest this. Its extraordinary breadth is also problematic, as a staff 9 cm thick could hardly have been held comfortably in the hand (this is slightly more than the diameter of an average wine bottle), and at 2 m long would have been very heavy indeed. Secondly, the other grave-goods are in no way unusual, consisting of jewellery, a knife, a pottery vessel and so on, the only exception being a flat stone at the foot of the grave which Hjørungdal sees as a symbolic boundary between different worlds or states of being (1989: 103). This is certainly a puzzling grave, but in my opinion its early date and lack of additional distinguishing features make a link to sorcery very questionable.

As Anna Lihammer has noted (2012: 198), it is possible that wooden staffs once far outnumbered those of iron, but the majority have naturally perished. In some cases they do not seem to have been recorded even when found. An example here is the cemetery from Tuna i Badelunda, in Swedish Västmanland, where several very rich female burials were excavated in the 1950s. Organic preservation was unusually good, as can be seen in the photographs of the fieldwork, and in the ninth-century boat grave 75 a long wooden staff can be clearly discerned although it is not mentioned in the report other than among “interdeterminable wooden pieces” (Nylén & Schönbäck 1994: vol. 1, 51–3, vol.2: 114, 120; Lihammer 2012: 198).

One further wooden staff is not from a burial context, but was found in a Danish bog at Hemdrup, Næsborg sogn, in Jylland in 1949 (Skautrup 1951; Andersen 1971: 18–21; Gardeła 2012: 130f, 2016: 105f, 274f; Fig. 3.102). When discovered, the staff stood almost vertical in the bog, thrust down into the mud and water. Measuring 0.5 m in length and made of yew, the staff is carefully polished and faceted in a manner similar to the piece from Oseberg. It tapers gently from 3.4 cm in thickness at the end which was nethermost in the bog to 2.1 cm at the other end, which is marked by fire. The thicker end has a bevelled cut resembling the mouth-piece of a flute. Along the broader half of the staff, lines have been deeply cut in the wood to make a series of rhomboid shapes, within which are several more shallowly incised figures and two runic inscriptions (Fig. 3.103). The form of the runes and the presence of a triquetra knot date the staff to the tenth century, perhaps as late as the first half of the eleventh (Andersen 1971: 20).

The interpretation of the images and the runes is difficult, both in terms of understanding their visual scheme, identifying what they are meant to signify, and in decoding their meaning. Four of the figures appear to be animals with short legs, tails and long, elongated bodies. One is drawn in a rhomboid by itself, two appear together in another rhomboid, and the fourth is drawn in the ‘central’ rhomboid alongside one of the runic inscriptions, on the opposite side of which is a human figure. The second runic inscription appears in a field by itself, as does the triquetra and two more abstract designs that are very hard to decipher.

Three main interpretations have been proposed. Skautrup (1951) suggests that the staff was a throwing stick belonging to a shepherd, and that the carvings are idle graffiti depicting the owner and their dogs. One of the runic inscriptions, which mentions a woman’s name, is seen as an ownership mark. Andersen (1971) views the staff as a message of impending war, carried from place to place as an acknowledged signal for mobilisation; he supports this interpretation with reference to other staffs that were used in this way in post-medieval times. More recently, Back Danielsson (2001, 2007: 233–9) has interpreted the staff as a tool of seiðr, depicting a shaman with helping spirits, and with inscriptions carved to drive away a being of sickness. The rhomboid forms are held to resemble the scales of a snakeskin, and the flute-like incision is used to argue that the staff was an instrument played to achieve an ecstatic state.

Fig. 3.102 The wooden rune-staff from Hemdrup in Jylland, Denmark, (after Andersen 1971).

The two earlier interpretations, especially that of Skautrup, are hard to credit today. The carvings are clearly very much more than casual doodling, and the idea of the staff as a ‘War Arrow’ has no support in any source relating to the later Iron Age (Andersen does, however, offer a nuanced and undogmatic reading of the object). Back Danielsson’s suggestions are plausible and clearly of relevance to the present discussion.

The runes are crucial, but there is scholarly disagreement as to how they should be read, and how the variant readings should be understood (Moltke 1976: 289f; Nielsen 1984).

Fig. 3.103 An expanded view of the carvings on the Hemdrup rune-staff, showing the lozenge pattern, runic panels and a number of figures (after Andersen 1971).

The different versions on offer from the runologists translate approximately to:

•‘The flying (fever-devil?) never got you, Åse [undecipherable]’ (Moltke)

•‘The flying one never conquered you. Åse is lucky in battle.’ (Nielsen)

Nielsen (1984: 220) sees the inscription as a charm of protection, carved on the staff as a love-token to the woman Åse, who is the figure depicted on the object together with her dogs. Like Skautrup’s view of the shepherd, this interpretation goes far beyond what we can actually read from the staff, and the inference of relationships, gifts of affection and so on really cannot be supported from the evidence. Back Danielsson (2001: 74) is right in also stressing the marked androcentricism of these earlier interpretations.

It is clear that the runes concern a flying being of some kind, and a form of spirit sending or charm against illness is a reasonable interpretation (cf. Röstberg 2009). Back Danielsson’s reading of the staff is in no way anachronistic in terms of what we know of the later Iron Age, and indeed fits perfectly with the picture that I have argued for here. Like the previous interpreters, however, the problem is the level of detail to which she takes this, and the process of inference from the material to her conclusions. Pursuing the theme of flight, she sees the small markings on the body of the human figure as a ‘feather-like garment’, indicative of shape-shifting (Back Danielsson 2001: 74). Perhaps the markings are indeed feathers, but they may equally represent fur, or chain-mail, or ‘wounds’ made by repeatedly stabbing the figure to inflict injury, or any one of several other possibilities. Certainly the animals may be spirits themselves – as we shall see below, there are written sources which speak of causing such creatures to ‘run far into the night’, and this is perhaps what we see on the Hemdrup staff (cf. Fóstbrœðra saga 9). However, they may have other, quite different meanings. The rhomboid ‘snake-scales’ are subjective impression alone, and the flute-like incision similarly does not mean that the object can be ‘played’ (though we might think here of the Irish instrument from Becan, noted above, and of course this does not preclude metaphorical associations). The analogies cited by Back Danielson derive from Eliade, and are not further specified.

The Hemdrup staff is clearly a very special object, both in its form, decoration and the context of its deposition. Given the runic inscriptions, the triquetra knot and the sheer specificity of the design scheme (it is not a random creation), I agree with Back Danielsson that it was an object connected with the supernatural. Further details are out of reach, though we may speculate that it might represent one of the more oblique kinds of staffs mentioned in the written sources.