We have already seen how even in the early sources there is mention of women practicing the arts of divining the future and clairvoyance, often through the use of specific tools such as knives, axes and especially belts (e.g. Lundius 1905: 8; Thurenius 1910: 396; Solander 1910: 24; Bäckman & Hultkrantz 1978: 59). Thomas von Westen mentions these in a letter from 1723 when he relates how soothsaying was done “belted” (von Westen 1910: 2). Solander also records how Sámi women prayed to Passevare-Ollmaj, the ‘holy men of the mountain’: så hänger hon upp sitt bälte, och därigenom frågar, ‘she hangs up her belt, and asks through it’ (Solander 1910: 24; Lundmark 1987: 167). The priest Henric Forbus seems to be describing something similar in 1727, when he tells how women would sing to the belts så länge at instrumentet blir rörligt, “until the instrument [i.e. the belt] begins to move” (Forbus 1910a: 34) – the belt presumably having been hung up first. This seems to have been particularly a southern phenomenon, but men too used belts for this purpose, as we see in the description of one of Silbo-gåmmoe’s sons who was also a noaidi. This man, Spå-Nila or ‘Nila the Seer’ (1822–99, also known as Stor-Nila, ‘Great-Nila’), inherited his mother’s scarf of squirrel tails, which he used in his own ritual performances. We read that he carried the scarf in his belt, and let one end drag on the floor as “a sign that he intended to practise divination” (ULMA 5585: 64; see Lundmark 1977: 61–2 and 1991 for a full biography of Spå-Nila).

An alternative method of divination was to use aqvavit or snaps, the Scandinavian strong liquor, especially to find out the identity of a thief. During his attempts to convert the Sámi, Henric Forbus drew up a detailed list of 72 questions that he routinely put to the people he encountered in an effort to discover if they held allegiance to the old religion; of these questions, number 45 reads Har tu sedt i Bräntwin hwem som stulit hade?, ‘have you seen in the aqvavit who has stolen?’ (Forbus 1910b: 73) This much-neglected document incidentally forms one of the most depressing witnesses as to the true character of the Lappland missions, as one can clearly perceive behind the questions the progressively increasing mental and corporal pressure being brought to bear on the subject – the list is a testament to the insidious process by which the traditional knowledge so deeply embedded in the Sámi psyche was deliberately undermined and dismantled.

Healing was another ability of female Sámi shamans and also of Thurenius’ gåbeskied, who could furthermore affect the weather (1910: 395), and there are several examples of women who used their skills for this purpose. One such was Lapp-Stina, who cured several cases of sickness in Ångermanland where she lived as a sockenlapp. Her powers were attested to by several priests – one of whom had his sight restored by her – in full knowledge of the conflict that their testimony created with their own religious beliefs (Laestadius 1959: 96). Lapp-Stina’s explanation for her curative skills was that she had learned them from her ‘godparent’, a ‘woman of the underworld’ (Laestadius 1959: 96) who she said had been present at her christening. The same source records that she would mentally converse with the spirit woman before beginning to effect a cure. The tradition of female healers has been among the most persistent into modern times, and continues today in northern Norway where its practitioners, considered to be ‘non-Christian’, are known as Mir’ku-ákku (Bäckman & Hultkrantz 1978: 89).

Women also assisted male noaidi in healing rituals, as in the above-mentioned case of the two described by Leem (1767: 476) who attended a curing ritual dressed in their finest clothes, with linen hoods over their heads but without their belts. These women, called Sjarak, were accompanied by an adolescent girl whose role in the ritual is unclear. The mortal female participants seem to have been reflected in the ‘invisible assembly’ (usynlige forsamling) of spirits and noaaide-gadze who responded to the sorcerer’s summons, a gathering of beings which was presided over by Aarja. Among this assembly were two spirit-women whom Leem describes as being those “som benævnte Aarja havde med sig”, “whom the aforesaid Aarja had with her” (1767: 476). These women were called Rudok, and are discussed in greater depth by Myrhaug (1997: 71ff).

As with other areas of Sámi religious behaviour, the relationship between women and animals – including their spiritual forms – was also full of contradictions. These are exemplified once again by Rijkuo-Maja. According to Brännström’s ethnographical notes made in Arvidsjaur in 1931 (ULMA 4373a: 53) she employed only one shepherd despite the size of the herd, and could pick out individual deer at great distance; there are other traditions recording that “she ‘knew’ her reindeer in a special way” (Lundmark 1987: 158). Several records show that this relationship was widely believed to have continued after her death. When Rijkuo-Maja’s family disobeyed her wishes for a non-Christian burial, within a few years the reindeer herd had either scattered irretrievably or been killed in drift ice – as she had herself prophesied if her instructions were not heeded (ULMA 4373a: 49; NM 573, 638, 641). Interestingly, one informant also mentions that she did not need dogs because the wolves were in her service (Lundmark 1987: 159) – a strange suggestion given the traditional Sámi antipathy to these animals (cf. Larsson 1996 & 1998). She seems also to have adopted an unusual role in relation to the other animals in her home tract, placing both wild creatures and edible birds “under her protection”. If hunters nevertheless killed animals in the area against her wishes, she compelled them to sacrifice their prey before a great pine tree, with a human face carved in its bark (ULMA 4373a: 107).

Other animals are also mentioned in association with female Sámi sorcerers, as in the case of Silbo-gåmmoe who repaid a stranger’s gift of meat by apparently conferring upon her some kind of animal spirit-guide in the form of a white dog, who “will go before you all the time” (NM 1032). We may note that the recipient of the spirit-dog, Brita Maria Nilsson of Grundträsk, had very little idea of what Silbogåmmoe was talking about but nevertheless interpreted it as something positive!

What links all these ideas is the notion of shamanic helping spirits, which often took animal form. Although as we have seen Lundius (1905) rejected the idea that Sámi women could have such helpers due to their ‘debilitating weaknesses of distinct kinds’, there are clear indications that this did not necessarily reflect the reality of Sámi religion; we may also speculate that Lundius’ opinions were influenced more by his own cultural views on women than by information he received from the Sámi. Among the early sources, Leem is perhaps the most specific when he relates how the Trold-Qvinder described above have worked magic “i Svaners, Ravnes, Falkes, Giæsses, Anders, Maagers, Sælhundes, Marsviins, Hvalfiskes, samt andre Fugles, firefodte Dyrs og Fisekes Gestalt”, that is ‘in the form of swans, ravens, falcons, geese, ducks, seagulls, seals, dolphins, whales and other four-footed creatures and fishes’ (Leem 1767: 453–4).

Like the women described by Leem, Rijkuo-Maja seems to have been especially associated with birds, with the raven, eagle and bench-jay being specifically noted as being among the creatures that she ‘protected’ in her reindeer pasture. The bench-jay reappears as part of the name of another guaps from Arvidsjaur, Guoksag-gummuo, and Lundmark considers these birds to represent helping spirits of the theriomorphic kind (1987: 166; her habits are further described in Ruong 1944: 125).

Like Rijkuo-Maja, Guoksag-gummuo also made sacrifices and worshipped pine-trees with anthropomorphic features carved on them (Manker 1957: 225), though this was not a custom specific to female sorcerers. Manker’s survey of cult sites lists several examples of such trees, including pines at Maskaure (ibid: 225), Tomholmen near Luleå’s Gammelstad (ibid: 187, pl. 154–5), a very large example at the Avgudahällan or ‘worship-rock’ by Kaskajaure (ibid: 213, pl. 205), Viktorp in Meselefors and Råseleforsen in southern Vilhelmina (ibid: 271–3, pl. 294– 7) and Offerdal in Jämtland (ibid: 289). Offerings were also made to pines which had not been altered by carving, as for example the sacred trees at Seitejaure (Manker 1957: 224) and the uhriaikki pine tree at Markkina in Enontekiö, Finland (Itkonen 1946: 48; Manker 1957: 99f, pl. 4–5).

These trees may have had a connection to helping spirits in addition to being worshipped in their own right, or as expressions of the mystical power of certain forms of topography – an example being the pine at Markkina mentioned above, which was situated on a promontory at the confluence of two watercourses, a so-called skaite place (Johansson 1941: 61; Manker 1957: 100). This particular site is a good illustration of the special relationship that some Sámi sorcerers – though perhaps not all – seem to have had with individual trees as the residence of their helping spirits. Markkina was the scene of the resolution of a famous spirit duel between the two male noaidi Kielahis-Niilu and Nahkul, related by Johansson (1941: 61ff), Manker (1957: 100) and Lundmark (1977: 59). A long-running feud between the two men resulted in Nahkul attacking his enemy with the assistance of his helping spirits, while Niilu was on his way to the market at Markkina. Witnesses related that Niilu came driving his sled at full speed into the settlement, dripping with sweat and swinging his arms as if warding off invisible things flying about him in the air, and then ran as fast as he could to the pine tree on the hill. The tree was at that time very young, and Niilu is reported as shouting during his run to the tree, “Bara jag hinner till min lilla tall, så klarar jag mig nog”, ‘if I can just make it to my little pine, I’ll be alright’. Upon embracing the tree he relaxed and the attack upon him ceased. Manker (1957: 100) records how on other occasions Niilu himself was seen with his own helping spirits who seem to have resided in the tree, once pulling his sled in the form of a wolf and a second time as an invisible force making the sled appear to move by itself. His good fortune was attributed to a positive relationship with the dead lying in the churchyard which was situated on the hill below the sacred pine.

Such trees appear in other shamanic cultures, sometimes as the place of birth of the shaman and often as the tree from which the drum is carved, thus forming the personal link between the shaman and his or her vehicle for spirit journeys. In Sámi culture, the ‘drum tree’ was often one that had been struck by lightning (cf. Lundmark 1977: 59, and the story of Ol Sjulsson’s cutting of drum-wood related by Pettersson 1979: 77f). In the specific context of women and Sámi religion, both Lundmark (1987: 167) and Eliade (1989: 69) have noted the similarities that the combination of birds and sacred trees – as in the case of Rijkuo-Maja – bears to Buryat myths of the origins of female shamanism. The tradition of such carved faces may also have a parallel in a similar custom in the Eastern Woodlands of North America, in the same area as some of the most complex concepts of the Owner of the Animals mentioned above. Here Fenton (1987: 206–9) has noted the Iroquois tradition of carving a False Face on living trees, within the context of the Society of Faces (McElwain 1987 discusses further parallels between Iroquois and Sámi belief; cf. Brown 1997).

The nature of Rijkuo-Maja’s relationship to the animals of her territory also raises other intriguing possibilities for the interpretation of female sorcery among the Sámi – and by extension its links with the Scandinavian volur – as her actions have parallels with the functions of the Rulers discussed above.

Two main approaches have been adopted to the female noaidi and similar figures in the later sources. Bäckman suggests that people such as Rijkuo-Maja cannot be considered true ‘shamans’ as they operated on an individual basis outside the context of a community. Such ‘shamanism’, she argues, had no religious basis, attracted no believers, and functioned purely for divination (Bäckman & Hultkrantz 1978: 84–5). In such circumstances, which resemble Rydving’s definition of a ‘postshamanistic’ phase, women may have found it possible to “perform in new roles which were previously taboo to them” (Lundmark 1987: 167). However, this does not take into account the wide range of functions that these women performed. We have seen above examples of not only divination but also healing and drum rituals – magical violence is considered below – together with the same kinds of sacrificial behaviour and possession of spirit helpers as characterise the male noaidi. The second of the two approaches would therefore seem the most likely interpretation, in Lundmark’s words that “they are possibly latter-day exponents of an even earlier, extant shamanism with female characteristics in the Saami area” (1987: 167f).

Interestingly, Lundmark draws the ultimate support for his argument on the existence of female Sámi ‘shamans’ from the volur of the Viking-Age Scandinavians, whose existence he accepts without question (Lundmark 1987: 168; see also Lundmark 1977: 62 for a more developed appraisal).

Enough evidence has been presented here – at deliberate length in view of the fact that the Sámis were the Viking-Age Scandinavians’ co-habitants of the peninsula – to suggest that female sorcery was a major element of Sámi religion in the post-medieval period, and that a good case can be made for this situation being a continuation of a long-standing tradition. We have also seen how specialists in Sámi religion consider the existence of the volur as female practitioners of shamanistic rituals to be so secure among the Scandinavian societies as to be a valuable support for discussions of such figures in the Sámi area.

Perhaps the most important aspect to note about the Sámi complex of sorcery, this noaidevuohta, was the deep division of all its rituals along lines of gender. As we have seen, there were specific gods for men and women, and different spirits too. The same is true of the rituals of the noaidi, and it is not going too far to talk of a ‘double religion’, a dual scheme reflecting a kind of submerged conflict between the sexes.

This is not the place for an extensive discussion of the Sámi shamanic rituals, which have attracted a considerable literature. In addition to the general works listed above, the reader is directed to Clive Tolley’s 1994 analysis of the first known description of a noaidi’s performance in the Historia Norvegiae, Hans Mebius’ work on sacrificial rituals (1968, 1972) and the very useful overview in Bäckman & Hultkrantz (1978: 62–90). Here we shall instead draw out key themes and functional arenas.

Håkan Rydving has isolated four aspects of Sámi rituals, all inter-related and interdependent, as being of primary importance when interpreting their meaning:

•the spatial location of the ritual

•the time when it is performed

•the constructions of sex or gender with which the ritual and/or its performer(s) are encoded

•the economic context of the ritual, i.e. what it relates to in the wider social sphere

Their purpose could vary, with different ceremonies for different kinds of objectives. Again, most of our data comes from the South Sámi area. Some of these rituals were rites de passage, such as the important process of name-giving, though we know few details of the ceremonies performed for other life-stages such as puberty and, not least, the burial of the dead.

Other rituals were linked to calendrical or seasonal observations, such as the bear ceremonies in May, the offerings of lichen and porridge to the sun at midsummer, and the great autumn sacrifices to the highest god. In the holy month approximating to November, called bassemánnu in SaN, major offerings were made to all the gods and especially to the moon. These sacrifices set the pattern for the year, divided into 13 months and eight seasons, and formed around the interaction between the natural environment, nutritional sources and the movements of the reindeer. The whole system also moved on a spatial axis, according to the terrain through which the herds travelled and the relative position of the treeline.

One of the main ritual territories of the noaidi concerned situations of crisis. These could include times of difficult weather such as storms, or a failed hunt, but also more domestic circumstances such as outbreaks of severe illness or the necessity to change a person’s name. The rites of hunting and divination were also constants of the noaidi’s calling.

The drums were used for divination and clairvoyance, to predict the outcome of hunting expeditions, to cure the sick and as a first step in negotiations with the spirits. The exact function of the drum is unclear, and it is possible that different types were used in different ways, in different places, at different times. Lousie Bäckman has recently speculated in oral presentations, though not so far in print, that for the most powerful sorcery the drum was not beaten at all, but waved in the air. This puzzling behaviour accords with several early ethnographies, and it may be that the drum served as a symbol of transport more than an aid to attaining an altered state of consciousness. It is interesting that the Historia Norvegiae’s account of a Sámi séance clearly mentions a drum, but it is merely carried by the noaidi as he leaps about. It is decorated with images of transportation (an oared ship, bridled deer, snow-shoes) and these are expressly described as being the means whereby the spirits travel on the noaidi’s errands (cf. Tolley 1994: 136f).

These spirits were crucial, functioning both as ritual tutors, guardians and assistants. Each noaidi had his own relationship with the individual spirits, and the two were bound together in various forms of symbiosis.

Following Bäckman and Hultkrantz, Tolley (1994: 139f) has isolated the main elements in the Sámi shamanic séance based on a composite of all the early descriptions. Having prepared for his rituals by fasting, the noaidi takes various forms of intoxicating drink. The drum is brought into the kåta through the sacred rear door, and sometimes warmed by the fire to prepare its skin. The noaidi’s dress is considered below, but having arranged his attire the noaidi begins to beat on the drum or wave it around. As we have seen, he is accompanied by female singers, and occasionally men seem to have added a lower tone to the jojk. Sometimes the singers narrate the path that the noaidi will follow through the spirit realms. The noaidi often runs about the kåta, sometimes picking up hot coals or cutting himself without effect. His body has become ‘hard’ and sometimes his skin noticeably darkens, presumably with diffused blood.

After a period of drumming the noaidi may begin to foam at the mouth, fall to his knees and begin a high-pitched jojk. He collapses and apparently cease to breathe. The assistants watch over his prone body and do not cease their chanting. The trance seems to have lasted between thirty and sixty minutes, after which the noaidi’s breathing slowly returns to normal and he regains consciousness (see Bäckman & Hultkrantz 1978: 92–106 for a full review of Sámi trance states). The jojk singing increases in tempo as the noaidi comes back, guiding him home. His awakening may be at the call of a single girl.

The noaidi raises himself and begins to softly beat his drum. At this point he sits in reflection for some time, recovering his strength, before narrating the course of his journey and experiences to the onlookers. In some of the accounts, the noaidi also makes sexual allusions to the young woman who brought him back from trance, making copulating gestures to her and displaying his genitals.

A major part of Sámi ritual, intimately connected to the ‘soul’, was the concept of the jojk (pronounced ‘yoik’). This unique form of semi-ritualised singing was central to the world of noaidevuohta and today still forms a fundamental part of Sámi life (Arnberg et al. 1997).

The concept of performance was crucial to the meaning of jojk, which often functioned as a mnemonic to recall things considered to be important in a non-literate society. There were jojks to bring to mind places, people, animals and objects, and also events that brought these things together. Partly ad hoc compositions in a ‘poetry of the moment’, jojk also worked within a constant tradition of basic form. There was a broad terminology of jojk which included both worded and wordless forms. In some senses it is possible to speak of a philosophy of jojk in Sámi culture, embracing its importance for religion and its key role in understanding the world-view of these people.

The jojk and a variant of special songs called luohti were also constant features in the rituals of the noaidi, and provided the background to all the practices of noaidevuohta. They were the means of communication with the other world, the language of trance and in some ways a rhythm of life itself. One of the things that characterised the emptiness of the world of the dead was the absence of jojk there. This was one of the contexts in which the jojk was important, in terms of remembrance of the dead and the maintenance of contact with them through the medium of the song.

Every person also had their own jojk, conferred by their relatives during childhood, and this individual melody could be used in conversation in place of a name. These name-jojks also found their way into the larger jojk compositions with a semi-narrative function. In this sense jojk was a means of communicating between people who knew one another well, and who would understand the references in the sounds (Kuoljok & Westman 1998).

Unlike most of the circumpolar traditions, we know little of the noaidi’s dress. Few early authors make any mention of special clothes, and in fact where the preparations are referred to the descriptions differ widely.

Thurenius (1910: 396) says that the noaidi dressed in his best clothes and was carefully turned out, having combed his hair and taken a bath. Leem (1767: 477) records that the noaidi removed his hat and loosened his belt and shoes. Olsen (1910: 43ff) mentions two different actions of the noaidi, both highly specific. On one occasion he turns his clothes inside out and wears them backwards, while on another he performs his rituals naked.

It is possible that colour symbolism may have played a part in the noaidi’s clothing. Red was often associated with magic and sacrifice, while white represented the sun and black stood for the dead.

Among the most fundamental items of equipment in the shamanic repertoire – particularly in the popular imagination – are drums. They are found in most parts of the circumpolar region, especially in Siberia, though they are by no means universal even there. In the Sámi noaidevuohta there is no doubt that the drum was vital.

The primary requisite of the noaidi, there were once many hundreds, if not thousands, of these drums. Today less than eighty examples from the post-medieval period survive, scattered throughout Scandinavia and the anthropological collections of the world. Catalogued and described by Ernst Manker (1938, 1950), the drums occur in several different forms with discrete distributions. The drums were constructed in two basic types – frame-drums (SaL gievrie; Fig. 4.3) in the south, and bowl-drums (SaL goabdes, SaN meavrresgárri; Fig. 4.4) in the north. A full guide to these objects, their design and iconography may be found in the four synthetic publications to have appeared since Manker’s great work (Kjellström & Rydving 1988; Ahlbäck & Bergman 1991; Westman & Utsi 1999; Westman 2000).

Fig. 4.3 A Sámi shamanic drum of the frame-type, with its painted skin full of images used in the noaidi’s performance; a drum hammer rests on the surface (photo by Åge Hojem, courtesy of NTNU Vitenskapsmuseet).

Within the images painted on the surfaces of the drum-skin are eight patterns of compositional variation, hinting at changing traditions and functions within Sámi ritual practice. The design scheme of the drums is too complex for a full discussion here and has been treated extensively by Manker and others, but we can note that the Sámi themselves tended when questioned to emphasise hunting themes in interpreting the images, whereas scholars have preferred to concentrate on mythological explanations; the truth probably lies somewhere in between (Fig. 4.5).

Both Niurenius and Steuchius (Bäckman & Hultkrantz 1978: 73f) noted that different kinds of drums were used for different purposes. One, which was called by the Swedish name of wåntrumma, ‘hope- or expectation-drum’, was used for divination and prediction, and for the provision of good fortune. Importantly, there seem to have been few restrictions as to who could use this kind of instrument. The second form of drum was reserved for the noaidi, and called a spåtrumma, ‘prediction-drum’, by the Swedes. Oddly considering its name (which we should remember was the missionaries’ coinage, not the Sámis’), this type was perceived as a weapon, a skadetrumma or ‘damage-drum’ with which the noaidi could cause injury and harm. Both types of drum were decorated, but differently according to the missionaries. We do not know how these recorded drum types and design schemes relate to the examples that survive.

Fig. 4.4 A Sámi shamanic drum of the bowl-type, probably from Lule Lappmark (photo courtesy of Nordic Museum, Stockholm).

Fig. 4.5 The design scheme of the drum shown in Fig. 4.4. (photo courtesy of Nordic Museum, Stockholm).

Some accounts suggest that the drums were thought to speak, their booming rhythms reflecting the voices of the spirits (Kildal 1945: 137). These beings were first summoned and then sent into the drums, where the noaidi would converse with them.

The drum was held horizontal in the left hand, and beaten in a lateral motion with a hammer, often of bone or antler with a double head (SaN ballem or viæzer, SaS ståwro or viedtjere). Several examples of these hammers have been found, primarily in Norway, and others are known from excavated medieval contexts far older than the earliest surviving drums. One of these, from Nordset in Øvre Rendal, Opland, is dated by its carved decoration to the period 1000–1200 (Gjessing 1945; Manker 1950: 442; Zachrisson 1991b: 86ff), and has fragments of Ringerike stryle ornament that may indicate some degree of hybridity – including of use? – with the Norse inhabitants of the region (Bergstøl 2008a: 98ff; cf. Pareli 1991; Hansen & Olsen 2004: 107; Fig. 4.6).

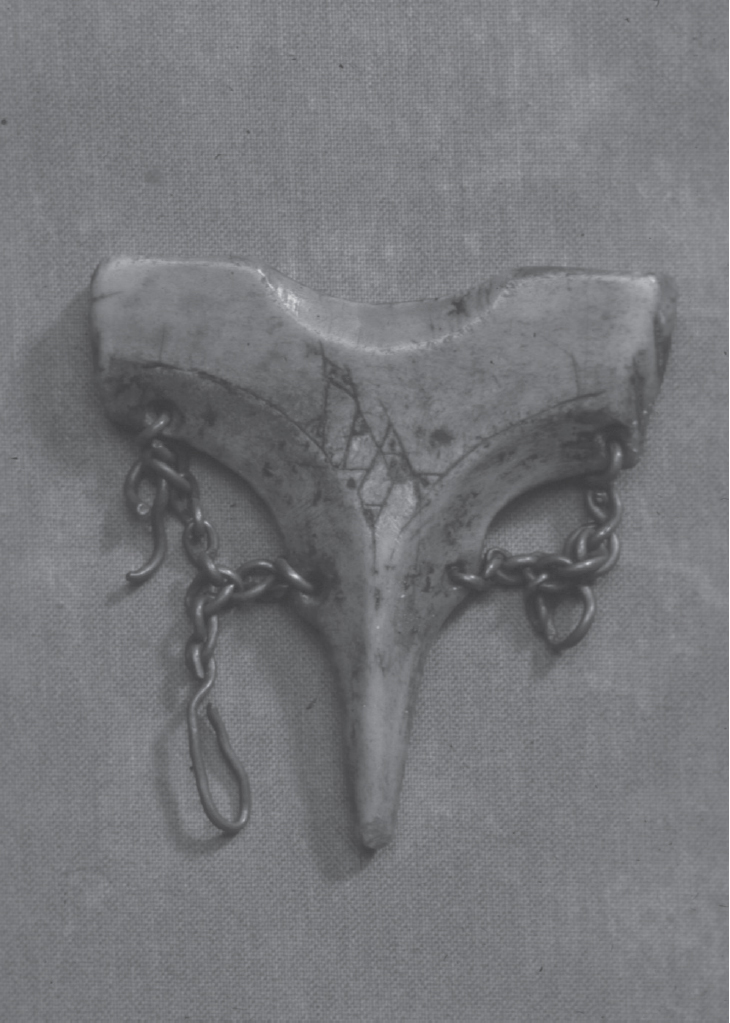

A small pointer called an árpa, SaN for ‘frog’ (SaS veike; Fig. 4.7), was placed on the drum-skin, the vibrations of which would make it jump about across the design of painted images, hence its name. Investigations of the nodal patterns of the drums indicate the árpa would have moved strangely, sometimes stopping suddenly, sometimes jumping quite high above the drum. The sequential movement of the pointer would trace out a path from one image to another, the meaning of which would be interpreted by the noaidi. Again, several examples of these pointers are known, often of brass, horn or bone, sometimes made of reused jewellery, pieces of metal and so on. Some of these pointers had metal chains and silver or brass ‘jingles’ hanging from them (SaS baja).

Fig. 4.6 A Sámi drum hammer from Nordset in Rendalen, Norway, dated 1000–1200 with decoration that mixes Sámi styles with Norse Ringerike ornament (photo by Thorguds, Creative Commons).

The rear of the drum was also festooned with objects, serving various kinds of amuletic and protective functions (Fig. 4.8). As we have seen, silver and iron nails could be attached for each bear-hunt that the drum had effected, and the penis bones of bears are also found hanging on the drum handles as especially powerful charms. Other objects found on the reverse of drums include coils of tin thread, brass rings, bear claws, the teeth of bears and beavers, and an array of coloured cloths.

The extent to which use of the drum was confined to the noaidi is problematic, as there are numerous documents relating that drums were found in at least half of Sámi households or even more (cf. Pettersson 1979: 77), especially in the southern area of Sápmi. They may have been used differently in different areas, and their use may also have changed over time. Leem (1767: 467), amongst others, also notes that the Sámi sometimes employed other objects to maintain a beat, such as barrel-lids and painted bowls – we can think here of the previous chapter’s discussion concerning the nature of the mysterious vétt in Norse sorcery.

Fig. 4.7 An árpa, the pointer used with a Sámi shamanic drum to interpret the images on its surface (photo by Jan Gustavsson, courtesy of Ájtte Svenskt Fjäll- och Samemuseum).

Other equipment The drum was not the only item of equipment used by the noaidi and their female counterparts. In an account written in 1774, Thurenius mentioned that for sorcery the noaidi would employ the drum, the belt, axes and knives (1910: 395). As we have seen in the discussion on Sámi sorceresses, belts are mentioned several times, either hung up and used for divination or worn as a signal that rituals were to begin.

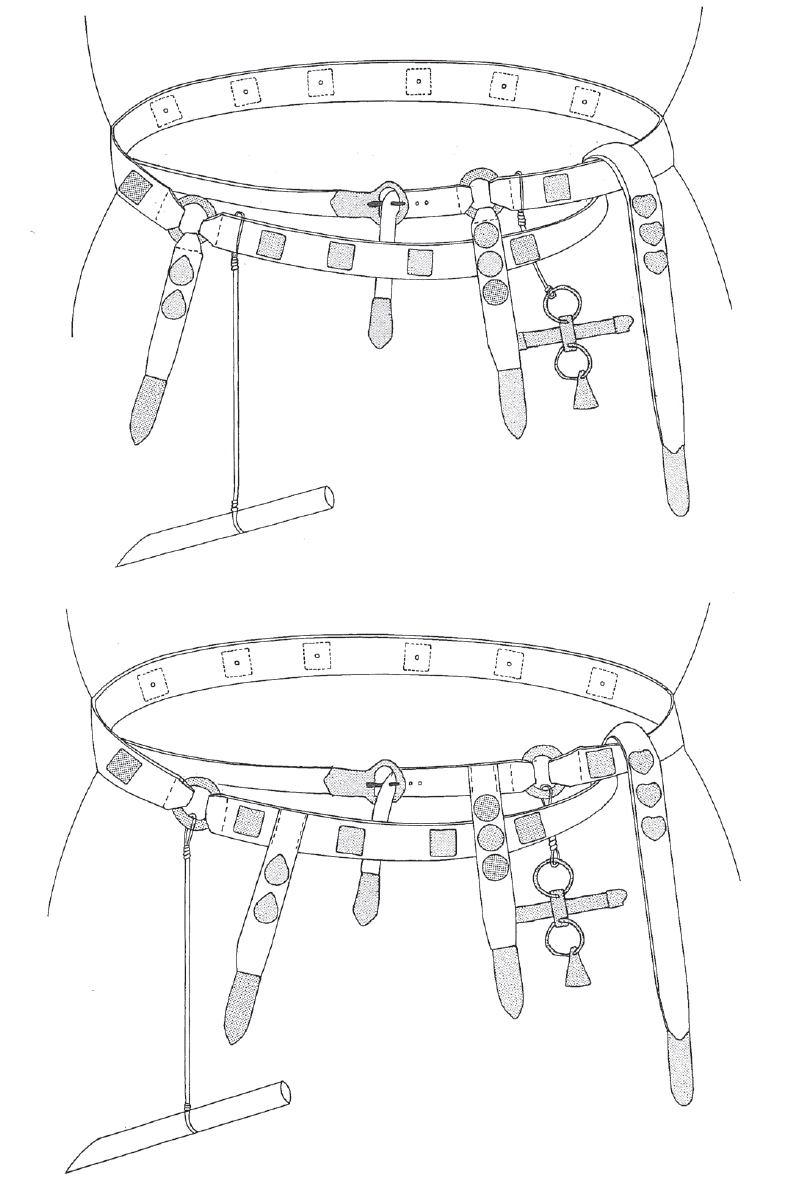

Two such belts have been preserved in the collections of the Nordic museum in Stockholm, of which one is now on loan to the Ájtte museum in Jokkmokk. Belonging at one time to the ‘spålapp’ gamm’ Nila – ‘Old-Nila’, who one should note is not the same person as Spå-Nila mentioned above – the belt had been in the same family for generations in Vilhelmina parish in Västerbotten, and was finally collected in 1895. Made of leather and fur, and decorated with cloth and metal mounts, the entire belt is hung with objects. These include a needle-case, knife, brass rings, bird claws, the penis bones of bears, and sealed leather bags whose contents is unknown.

Fig. 4.8 The reverse side of a Sámi shamanic drum of the frame-type, probably collected from Åsele. The tin-thread amulets can be clearly seen along with the penis-bone of a bear (photo by Jan Gustavsson, courtesy of Ájtte Svenskt Fjäll- och Samemuseum).

The belt is probably one of the few genuine items of a noadi’s dress that now survive. Very close parallels for it can be found in the belts of Netsilik shamans from central arctic Canada, of which a number of examples were collected by Knud Rasmussen on the 5th Danish Thule Expedition in 1923–24 and held at the National Museum in Copenhagen (Rasmussen 1931). These objects have a very similar array of pendant artefacts, including knives, animals parts, fur and bone. They are among the holiest aspects of a Netsilik shaman’s costume, and were the first priority items to be be requested for repatriation (most of the collection has now been returned to the Netsilik).

Headbands decorated in a similar fashion are also known from the Netsilik, and one comparable piece from a Sámi context is in the collections of the Nordic Museum in Stockholm – we can only speculate as to whether headbands were also part of the noaidi’s equipment. The clothes of Netsilik shamans and other ritual specialists were not different in themselves from conventional dress – again like the Sámi – but they could be hung with organic amulets of a kind that would not have been preserved from an early period. As an example, the Copenhagen collections include a jacket worn by a seven-year-old boy called Tertaq, onto which an entire raven corpse had been sewn; the child was thought to be the most spiritually powerful individual in the community, and its protection resided in his person.

At least one more Sámi sorcery-belt is known from northern Norway, though this is formed very differently from the Vilhelmina example. Collected from Kautokeino, this consists of linked plates of zinc and copper, fixed together with a piece of felt between them (Kuropjatnik 1997: 43 who also describes Russian Sámi parallels).

Later ethnographic sources also mention the belts of healing women, Dálkudiddje in LaL, which were made of tinder-wood (Sw. fnöske; for a reconstruction see Tunón 2001: 385; cf. Scott 1998). This would seem to be the exact same substance used in the belt of the volva Þorbiorg in Eiríks saga rauða 4. Among the Sámi healers, the belt had curative functions, sometimes combined with the use of snakeskin and venom. The noaidi also made use of fnöske smoke “för att utforska en hemlighet”, “to discover a secret” (Grundström 1943–44: 95; Almqvist 2000: 244).

There is also a small amount of evidence for the use of narcotics such as fly agaric (Itkonen 1946: 149), but this is a late tradition from the Inari area of Finland. In the early sources only alcohol is mentioned, often akvavit (Bäckman & Hultkrantz 1978: 93).

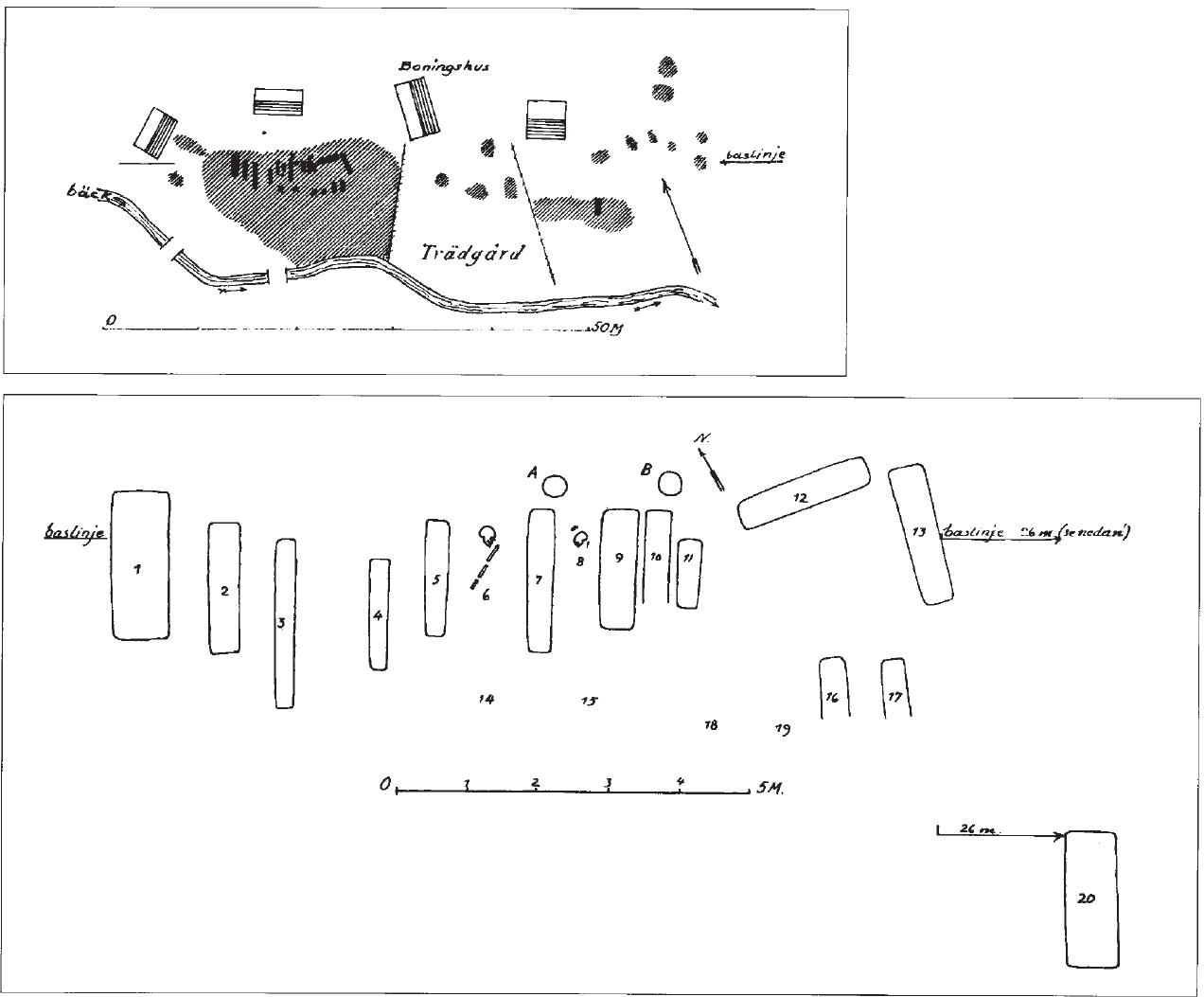

A special example of the material culture of noaidevuohta comes from an archaeological context, one of the most comprehensively excavated and studied Sámi localities in Sweden. The site of Vivallen, in the province of Härjedalen, lies in an area that was fully settled by Nordic communities. In 1913, Gustaf Hallström excavated 20 Viking-Age and early medieval inhumation burials here, all with grave goods characteristic of artefactual assemblages in Sámi cemeteries and sacrificial sites in northern Scandinavia (Fig. 4.9). The grave constructions, the mortuary behaviour in the form of birch bark shrouds, the disposition of the bodies, and even the physical anthropology, again all strongly indicate that the dead can be identified as Sámi (the Vivallen graves are treated at length in Zachrisson 1997, the main publication of the site building on earlier work by the South Sámi Project team members, with references therein). Further work in the 1980s located an additional burial, and also the remains of an associated settlement of kåta tent sites. Although I will not discuss this aspect of Vivallen here, we may note in passing that this is a particularly important example of a long-established Sámi community living south of the traditional cultural border (the Vivallen settlement is also published in Zachrisson 1997: 117–43).

Fig. 4.9 Orientation map and plan of the excavated Sámi cemetery at Vivallen in Härjedalen; grave 9 is that of the possible noadi (after Zachrisson 1997: 57; plans by Gustaf Hallström).

Fig. 4.10 Plan and photo of grave 9 at Vivallen, Härjedalen, during its excavation in 1913; note the body pressed against the side of the grave (after Zachrisson 1997: 58; drawing and photo by Gustaf Hallström).

In the present context we can focus on a single burial, grave 9, which contained the body of a well-built man in his fifties (Fig. 4.10). What marks the grave as unusual is that the dead man was buried not only with the kinds of objects most often found in male inhumations, but also with a number of artefacts which are conventionally associated with women (Fig. 4.11). Furthermore, in terms of their manufacture and the context in which they are almost always found, the ‘female’ artefacts originated within the Nordic culture.

The ‘male’ artefacts focus on a complex belt made in imitation of oriental warrior harness from the steppe region of the Volga basin, of a type found in both Viking and Sámi contexts (Fig. 4.12). The ‘female’, ‘Nordic’ artefacts include a necklace of glass and rock crystal beads of types found throughout the Viking world, a silver brooch that is probably Danish, a silver finger-ring, and a needle-case of a kind known from the Viking town of Birka in Lake Mälaren, and from Gotland. The most dramatic item of female apparel was a dress of linen, of a type found again in richly appointed women’s graves from Birka (the grave 9 assemblage and its parallels are discussed in detail in Zachrisson 1997: ch. 4).

Given the linen especially, it is not going too far to say that the man in grave 9 was buried clothed as a woman from the Nordic society, with appropriate dress and jewellery, but with the addition of a few accoutrements from the conventional wardrobe of the Sámi man. What does this mean? One of the most interesting explanations that has been put forward is that the dead man may have been a noaidi (Zachrisson 1997: 62). The elements of sexual transgression, cross-dressing and gender ambiguity that are found in connection with shamanism all across the circumpolar area in one form or another have been discussed in chapter 3 and will be explored again in chapter 5, and it seems clear that the combination of male and female dress in Vivallen grave 9 can fit well with a shamanic interpretation, though other readings are of course possible. We can also note that the grave itself was unusual, in that the dead man was buried pushed up against one wall of the grave. The excavators could find no indication of what, if anything, had lain in the empty part of the pit. Perhaps a noaidi was followed into the grave by the invisible presences that were part of his life?

This grave will be considered again towards the end of this chapter, but it can stand here as the only reasonable candidate that we have from the archaeological record for the burial of a Sámi ritual specialist. His appearance would have been striking indeed, and the man from grave 9 makes an interesting point of comparison with the possible vǫlva-graves that we have seen in chapter 3.

Fig. 4.11 The grave-goods of the man in grave 9 at Vivallen, Härjedalen (after Zachrisson 1997: 62; photo by Gunnel Jansson).

The sexual aspects of noaidevuohta are not anywhere near as evident as in the seiðr complex, but they are nevertheless present. For the Sámi, the fact that almost all our sources were recorded by churchmen rather than ethnographers is surely of significance here. Knowing the missionaries’ prudery and general antipathy, the noaidi would have been less likely to divulge these aspects of their rituals, and if they had done so the priests may not have recorded it.

Fig. 4.12 Alternative reconstructions of the oriental-style belt from grave 9 at Vivallen, Härjedalen (after Zachrisson 1997: 73; drawings by Martin Gollwitzer).

What little we have primarily concerns the rituals themselves rather than their purpose, though a certain sexual tension between the noaidi and the spirits can also be discerned (intercourse with the saajvh has already been mentioned above). All of our main data in this respect comes from the accounts of Isaac Olsen (1910: 46f), who as we have seen in the early 1700s noted how the noaidi would strip naked before commencing his rituals, an action that of course need not necessarily have sexual connotations. However, we should note the noaidi’s behaviour when awakening from trance, having been summoned back from his soul-journey by the jojk of his female assistant. It may not be irrelevant in this context that, according to Olsen, the woman should if possible be an unmarried virgin. Firstly the man sings to her, praising her skills at leading him back from his trance. The text continues:

… hand self bør nu at kyse hende baade for og bag, for hendis store velgiæringer som hun nu har giort imod hannem, og for hendis stor konst og visdom, og hun skal nu have og bruge mands lem effter sin villie og som hun behager, og hun skal nu bruge den til kiøre vid siger hand, og til drage baand, og drage den over sine axeler og skuldre som en prydelse, og hun skal have den til hammel baand og Jocka baand, og om sin hals som En kiæde, og over sine skuldre som en smycke og prydelse, og binde den om kring sit lif som Et bilte …

… he himself begins to kiss her now both in front and behind, because of her great good deeds which she has done for him, and for her great skills and wisdom, and she shall now possess and use his male member as she will and as it gives her pleasure, and she shall now make use of it with a sure hand, and as a draught-rope, and to drape around her shoulders as an ornament, and she shall have it as wagon-tackle and as sled-tackle, and around her neck like a chain, and over her shoulders as an ornament and decoration, and tie it around her waist like a belt …

Olsen 1910: 46f; my translation

The first part of this account is often repeated as an instance of sexual overtones in noaidevuohta, but the strange continuation of the statement makes it clear that this is not entirely the case. There are strong sexual elements, certainly, but the exaggerated uses to which the noaidi’s penis may be put surely take this into a different context (in these qualities the noadi resembles the Trickster figures of circumpolar shamanism, who often have enormous phalli which they roll up, carry on their backs or around their necks, and so on; see the stories in Radin 1956).

This sexual bond between the shaman and his assistants is a consistent feature of circumpolar belief, for example among the Chukchi (Bogoraz 1904–9: 448f). Similar elements are also found in Chinese religion (Malmquist 1974: 242). These will be examined in the next chapter.

We have seen many examples above of violent Sámi sorcery, most of all in the categories of noaidi such as the ‘eaters’. It says much that the most fundamental type-division of ritual specialists ranks three noaidi of aggressive and violent character against one further type whose task was to deflect the attacks of the others. These patterns are repeated throughout the corpus of noaidevuohta ceremonies.

The shamanic duel is a common theme, as is fighting through the medium of the spirits. We see the noaidi as the objects of fear, wielding their drums as weapons, and filling the air with magical projectiles. Like their Nordic counterparts, they were respected and held in awe at the same time, simultaneously terrifying but vital members of their communities.

Interestingly, there is evidence that some forms of violent magic in Sámi society were performed collectively by gatherings of noaidi, of the kind described by Skanke amongst others. One such was the very large meeting or ‘noyde-kionka’ which was called in an attempt to kill the priest Thomas von Westen, who as we have seen was one of the most zealous of the early missionaries and passionate in his hatred of the traditional Sámi religion. The ritual involved the sacrifice of no less than 14 reindeer bulls – an astonishing commitment in economic terms – but was unsuccessful (Kildal 1945: 138; Lundmark 1977: 57).

Another, rather strange, category of violence associated with Sámi belief comes with legends and stories surrounding the Northern Lights, known as Guovsahas in northern Sápmi (see Lundmark 1976a and b for a full discussion). The Sámi seem to have regarded them as some kind of vaguely undefined supernatural beings, associated both with extreme speed and fire, and many believed that they were clearly audible. It was thought dangerous to make a noise or otherwise attract attention to oneself when the lights were moving, in case they would become angry and kill the onlooker by burning, in a fashion somewhat akin to a lightning strike. In general there were clear associations between the lights and the idea of violent conflict. There are several stories describing how the lights are arguing or fighting amongst themselves or against others, and in many narratives they are associated with weapons, specifically of iron. These included swords, lances, and ‘flaming’ spears. The nature of the beings in the lights may be illuminated by Sámi beliefs from the Kola peninsula, where it was thought that they represented the souls of those killed in battle, continuing their war in astral form (Lundmark 1976a: 89). The Skolt Sámi refer to these spirits as ruutisjammij, ‘those who died by iron’, and again the link with armed conflict is striking. A similar connotation appears in the Norwegian dialect name blodlyse, ‘blood-lights’, and we can also note that they were associated with one of the few predatory animals of the far north, the arctic fox (Lundmark 1976a: 88).

These stories raise several intriguing possibilities, particularly because the association with battle is so uncharacteristic for Sámi society, which lacked organised warfare. We should especially note that none of the weapons mentioned were common among the Sámi – with the possible exception of the notion of the ‘flaming’ spear, which sometimes appears as a synonym for bear- and wolf-hunting spears – and it has been suggested that the weapon stories about the Northern Lights may be a Nordic loan (Lundmark 1976a: 89). This is especially interesting in the context of Nordic battle magic, the subject of later chapters, as it suggests a dim reference to some kind of armed supernatural beings, perhaps the souls of dead warriors, engaged in combat in the sky. Given the possible Nordic associations, the fact of the lights killing ‘like lightning’ is also striking in view of the complex relationship between the Sámi thunder-god and the comparable Nordic god, Þórr. On such meagre evidence this theme can be pursued no further, but it is suggestive as background support for the ideas presented more detail below.

Similar behaviour applied to the Sámi sorceresses. From post-medieval sources we begin to read of Sámi women performing spells to work magical violence, perceived as being directed for a malicious purpose. Thurenius, for example, mentions that the ability to harm or kill another person was a specific function of the gåbeskied (1910: 395), and Lundius says the same of the kwepckas (1905: 39). Leem wrote much of interest on female magic-users, whom he called Trold-Qvinder, ‘witch-women’, and amongst other harmful actions recorded that they could take animal shape to sink ships (Leem 1767: 453f).

One of the most dramatic early accounts is that concerning Kirsten Klemitsdotter, who died in the summer of 1714. The missionary Isaac Olsen writes that “she was an evil old noaidie woman who everybody feared and had performed much evil with her magic and caused the death of many people. And many praised God that she died and she was fetched by the noide-gadzerna at death’s door, while she was still alive” (Olsen 1910: 76). In at least one instance Silbogåmmoe, the classic ‘female noaidi’ discussed above, was also alleged to have performed violent magic. Together with her son, Spå-Nila, she was charged by one Sven Sjulsson of having killed the latter’s wife by witchcraft. The case appears unresolved, but took on a further dimension when Sjulsson himself died and Nila was successfully prosecuted for murder (Lundmark 1987: 162). Similar offensive spells were used by Spå-Ella – indeed, this seems to have been virtually the only kind of magic she performed. On two separate occasions when people annoyed her, she is recorded as having used her powers to nearly blind an old woman (the case noted above) and to have induced magical hallucinations of reindeer in a non-Sámi settler (Lundmark 1987:, 163f; ULMA 7017).

There are also tenuous linguistic sources which may suggest a connection between female rituals and violence – the SaN verb gievvot, noted above as one of the terms describing religious ecstasy, had a specific connotation in Jokkmokk where it referred to wrath in general and of women in particular (Rydving 1987: 195).

Having reviewed the practitioners, practices, world-views and sacred landscape of Sámi belief, we can conclude this section by summarising the various functions that noaidevuohta seems to have performed.

These included:

•finding game and performing hunting-related rituals

•foretelling the future (divination)

•uncovering secrets

•healing

•bestowing good or bad fortune (blessing and cursing)

•working illusions

•manipulating the weather

•causing injury to people, animals or property

•instilling fear or confusion in an enemy

•killing people

•providing protection from a hostile noaidi

•fighting/killing a hostile noaidi

•communicating/mediating with the dead

•communicating/mediating with the spirits of nature

•communicating/mediating with the unseen world(s)

•communicating/mediating with the gods

We have seen above that Sámi ‘shamanism’ was not a static, orthodox entity, but instead exhibited considerable regional variation in the form of its expression, which even in the same areas also changed over time. Secondly, the ‘Sámi shaman’ was in fact a large number of specialised types of shamans, and other practitioners, concentrating on one or more specific forms of work. Thirdly, both sexes seem to have played an important role in noaidevuohta, again with specific and precise differences in the social functions and abilities of men and women.

We can see that noaidevuohta was used for broadly the same range of purposes as the seiðr complex, including the prosecution of a specifically violent magic, both offensive and defensive. Used for killing and shamanic combat, a crucial difference from the Norse situation comes here with the surrounding social context: as far as we know the Sámi did not make war. We shall explore this in chapter 6.

To the extent that we may trust the sagas, there are several indications that the Norse identified the operative magical practices of the Sámi as something quite distinct from their own, while nevertheless retaining essential similarities.

This can be seen not least in a number of terms in Old Norse, such as finnvitka, meaning ‘to practise magic in a Finn way’ (Mundal 1996: 112). We also find the concept of fara til finna at spyria spá, ‘travelling to the Finns to receive a prediction’ and even euphemisms like gera finnfarar, ‘to pay a visit to the Finns’ (DuBois 1999: 129).

Another common pattern is that of magical instruction, when the Norse turn to the Sámi for help in these matters (Hermann Pálsson 1997: ch. 9). The classic example is that of Gunnhildr, later to be the wife of Eiríkr blóðøx, who in Haralds saga ins hárfagra (33) is sent to the Sámi by her father in order to be taught the skills of sorcery. She also seduces the men who teach her, and thereby persuades them to pass on additional magical knowledge. In another source, the fragmentary thirteenth-century Lífssaga Ólafs helga by Styrmir Kárason, we read of a sorcerer named Þórir who spends the winter of 1029–30 with a Sámi chieftain in order to learn magic from him. A much earlier text, Sigvatr Þórðarson’s Erfi drápa Ólafs helga from c.1040, seems to confirm this when noting that Þórir survived an otherwise fatal sword-thrust at the Battle of Stiklastaðir in 1030 due to the sorcery he learnt from the Finns.

Similarly, there are often sorcerous overtones to another common pattern in the sources, involving Nordic kings marrying, or simply sleeping with, Sámi women. The latter are often described as the daughters of Sámi rulers, as in the case of Snæfríðr in Haralds saga hárfagra discussed above, and in the epigraph to this chapter (the Drífa who hires a seiðkona to bring her husband back to Lappland is one such Sámi ‘princess’).

As we have seen, several sagas include passages in which Scandinavians hire Sámi to perform sorcery on their behalf. A useful example comes from Vatnsdæla saga 10. Near the beginning of the saga, the Norwegian Ingimundr Þórsteinsson receives a prophecy that will ultimately send him to Iceland, where he will become the long-lived patriarch of the people of Vatnsdal. The circumstances under which this prophecy is given, its consequences, and the material objects to which it incidentally refers are of great interest in the present context:

Ingjaldr fór heim ok bauð morgum monnum með sér. Síðan fór hverr sem boðit var. Þeir Ingjaldr efna þar seið eptir fornum sið, til þess at menn leitaði eptir forlogum sínum. Þar var komin Finna ein fjolkunnig. Ingimundr ok Grímr kómu til veizlunnar með miklu fjolmenni. Finnan var sett hátt ok búit um hana vegliga; þangat gengu menn til frétta, hverr ór sínu rúmi, ok spurðu at ørlogum sínum. Hon spáði hverjum eptir því sem gekk, en þat var nokkut misjafnt, hversu hverjum líkaði. … Finnan svarar: ”Þetta mun fram koma, sem ek segi, ok þat til marks, at hlutr er horfinn ór pússi þínum, sá er Haraldr konungr gaf þér í Hafrsfirði, ok er hann nú kominn í holt þat, er þú munt byggja, ok er á hlutnum markaðr Freyr af silfri; ok þá er þú reisir bœ þinn, mun saga mín sannask”.

Ingjaldr returned home and invited many people to the feast. All those invited duly attended. Ingjaldr and his men prepared a seiðr performance in the old manner, so that men could examine what the fates had in store for them. A Finn sorceress was among those present. Ingimundr and Grímr arrived at the feast with a large retinue. The Finn woman sat on a high seat, and was splendidly attired; men left their benches and went forward to ask about their destinies. She predicted for each of them that which eventually came to pass, but each took the news in a different way. [Ingimundr says that he does not want to hear his fortune told, but the woman tells it anyway, and predicts that he will settle in Iceland. Ingimundr scoffs at the idea, and says he has no such intention] The Finn woman answered: “What I am saying will come to pass and, as a sign of this, an amulet is missing from your purse – the gift which King Haraldr gave you at Havsfjorðr – and it now lies in the wood where you will settle, and on this silver amulet the figure of Freyr is carved and when you establish your homestead there, then my prophecy will be fulfilled.”

Vatnsdæla saga 10; translation after Wawn 1997: 204–5 with my amendments

Ingimundr is uneasy about the prediction, especially as the king suggests that maybe Freyr has it in mind that he should go to Iceland after all. Not wanting to leave Norway, Ingimundr nevertheless decides to make enquiries. He declares his intention of sending for certain Sámi, er mér sýni heraðs voxt ok lands skipun, þar sem ek skal vera, ok ætla ek at senda þá til Íslands (‘who can show me the extent of the region and the lie of the land where I will be living; and I intend to send them to Iceland’; Vatnsdæla saga 12). The saga continues:

Hann sendir eptir Finnum, ok kómu norðan þrír. Ingimundr segir, at hann vill kaupa at þeim, – “ok vil ek gefa yðr smjor ok tin, en þér farið sendiferð mína til Íslands at leita eptir hlut mínum ok segja mér frá landslegi.” Þeir svara: “Semsveinum er þat forsending at fara, en fyrir þína áskorun vilju vér prófa. Nú skal oss byrgja eina saman í húsi, ok nefni oss engi maðr,” – ok svá var gort. Ok er liðnar váru þrjár nætr, kom Ingimundr til þeira. Þeir risu þá upp ok vorpuðu fast ondini ok mæltu: “Semsveinum er erfitt, ok mikit starf hofu vér haft, en þó munu vér með þeim jarteinum fara, at þú munt kenna land, ef þú kemr, af várri frásogn, en torvelt varð oss eptir at leita hlutinum, okmega mikit atkvæði Finnunnar, því at vér hofu lagt ossí mikla ánauð. Þar kómu vér á land, sem þrír firðir gengu af landnorðri ok votn váru mikil fyrir innan einnfjorðin. Síðan kómu vér í dal einn djúpan, ok í dalnum undir fjalli einu váru holt nokkur; þar var byggiligr hvammr, ok þar í holtinu oðru var hlutinn, ok er vér ætluðum at taka hann, þá skauzk hann í annantholtit, ok svá sem vér sóttum eptir, hljóp hann æ undan, ok nokkur hulða lá ávallt yfir, svá at vér náðum eigi, ok muntu sjálfr fara verða.”

He sent for the Finns, and three of them came from the north. Ingimundr said that he wanted to make a bargain with them – “I will give you butter and tin, and you are to undertake an errand for me in Iceland and search for my amulet and report back to me about the lie of the land.” They answered, “This is a hazardous mission for Semsveinar to undertake, but in response to your request we want to make an attempt. You must now shut us up together in a house, and do not give our names to any man.” This was duly done. And when three nights had passed, Ingimundr went to them. They stood up and sighed deeply and said, “It has been hard for us Semsveinar, and we have had much toil and trouble, but nevertheless we have returned with these tokens so that you may recognise the land from our account, if you go there; but it was very difficult for us to search for the amulet, and the spell of the Finn woman was a powerful one, because we placed ourselves in great jeopardy. We arrived at a spot where three fjords open up to the north-east and in one fjord there were big lakes to be seen. We later entered a long valley and there at the foot of a mountain were some wooded areas. It was a habitable hillside, and there in one of the woods was the amulet, but when we tried to pick it up, it flew off into another wood, and as we pursued it, it always flew away, and some sort of cover always lay over it, so that we could not get hold of it; and so it is that you yourself must go there.”

Vatnsdæla saga 12; translation after Wawn 1997: 207–8 with my amendments

The same episodes are also referred to in Landnámabók, where the Sámi volva is given the name Heiðr, and we then read how: sendi hann [Ingimundr] þá finna tvá í hamforum til Íslands eptir hlut sínum, ‘he sent two Finns to Iceland in assumed shapes to recover his talisman’. While we clearly cannot take this as direct evidence for a Viking-Age reality, given the relatively low source value of saga prose, it nonetheless shows that this level of religious interaction was anything but unthinkable in the twelfth–thirteenth centuries. More importantly, it is worth considering just how many of the same functions that we have seen in this chapter and the preceding one are combined in this episode, and others like it. In view of the material previously reviewed, then this combination alone is a powerful argument that we should take these kinds of descriptions seriously in our attempts to reconstruct the context of Old Norse sorcery.

As Tolley notes (1995a: 62), there is another account of a similar mission in Óláfs saga Tryggvasonar (33) when Haraldr Gormsson sends a kunnugr maðr to ascertain details of Iceland – he too travels in beast shape, as a whale. Like the Sámi employed by Ingimundr, this man also encounters problems from spirits he meets on the way (see chapter 6 below, where the example is treated in more detail). It is not specified that this ‘knowledgeable man’ was a Sámi, but either this was the case – we know from Historia Norvegiae and other sources that Sámi sorcerers travelled in whale form – or else it implies that Norse sorcerers behaved exactly like their Sámi counterparts. Both of these conclusions are suggestive.

We can conclude this chapter with an archaeological example, and return to the possible noaidi grave from Vivallen. This provides us with an extraordinary chance to examine Sámi-Norse relations in a spiritual context. The cross-cultural grave-goods here can be considered in terms of the cultural biography of objects – essentially the ‘life story’ of artefacts from their manufacture to their entry into the archaeological record (cf. Marshall & Gosden 1999). Some of the items buried with the man in grave 9 are without doubt of non-Sámi manufacture (the dress, the beads, the jewellery and equipment). They were made in a permanent settlement – perhaps a village or even a town – by people who ethnically belonged to the Nordic cultural tradition. It is possible that they were made for trade with the Sámi, but more likely that they were produced as items for use by Nordic women. At some point, these objects moved across a cultural and ethnic border, and were acquired by the Sámi at Vivallen. This was probably a peaceful process, a matter of trade and exchange, as we have no evidence whatsoever for violent relations between the two cultures here. At this point the objects moved from the context of a settled, agrarian society to a mobile, nomadic one.

They also moved across a border of gender, and were transformed from items of women’s clothing and adornment to the possessions of a man, but in a special way which seems to refer to their former life as ‘female objects’. There is another transition too, of social context: in the Nordic society these were objects for everyday wear, but in the Sámi community they may have been the property of the most important individual in the group. The objects were thus altered from a conception of ‘dress’ and ‘jewellery’ to an understanding of them as items of ritual apparel and equipment: symbolic changes and functional ones.

The identity constructions involved here are worth considering. These are not just the bald ethnic statements of ‘Norse’ and ‘Sámi’, but also of settlers and nomads; agriculturalists and pastoralists; men and women, and a possible third gender; individuals of high and middling status; religious specialists and secular people; those who could travel between the worlds, and those who could not.

We should also understand that this was not a case of objects travelling completely away from one place to another, out of sight and out of mind. The Nordic population of the Vivallen area would have been quite familiar with the man in grave 9, and his community – after all, they lived practically side by side. We can only speculate as to whether this individual went about in life dressed as he was in death. Did his Nordic neighbours know how these objects were being used?

The similarities between seiðr and the practices of the Sámi have long been obvious, but I feel that a mistake has been made by most of the scholars who have previously looked at these phenomena, in that they have engaged themselves from the beginning with questions of ‘influence’ and ‘loans’ from one culture to another. In this chapter and the one preceding I have instead tried to analyse both seiðr and noaidevuohta as independent traditions in their own right, examining them side by side before comparing them directly. In one of her studies of religion in the high arctic, Pat Sutherland has perfectly expressed this situation; for her Palaeo-Eskimos and Inuit I have here substituted terms relevant to the present context:

Rather than viewing evidence for similarities between [Norse] and [Sámi] cosmological or religious beliefs as indicative of a ‘common symbolic reservoir’ … we might more aptly visualise parallel symbolic streams flowing from an ancient past and contributing in unique ways to the reservoir of beliefs among the northern peoples

Sutherland 2001: 143

In taking such a pan-Scandinavian perspective we have still taken a step closer to the circumpolar sphere to which others have run immediately, but with the necessary awareness of distance. We have seen how Sámi religion can without doubt be interpreted against the background of the circumpolar culture of which the Sámi are a part, but we cannot simply compare Scandinavia with allegedly parallel traditions further and further away across Siberia and the far north. If we are to move eastwards (and, to some extent, westwards to arctic Greenland and North America), then we must do so cautiously, critically, and specifically. We must also continue to pursue the unique traits that served to distinguish seiðr and noaidevuohta from each other, while bearing in mind the strands of interdependence that bound them together at a cultural frontier between the Germanic and circumpolar worlds. As far as possible, up to this point I have deliberately kept the discussion of Norse religion relatively independent of the labels used to characterise the belief systems of the arctic and sub-arctic. However, it is now time to enter another interpretive context, and to address the question of Old Norse shamanism.