The process of becoming a shaman often involved a process of initiation, either voluntary or involuntary. This could take a long time – even years in some cases – and might involve long-term sickness and temporary madness, or more short-term trials such as fasting or various forms of ordeal and tests of endurance. In several of the Siberian cultures, while dreaming or in a state of trance the shaman’s spirit form is dismembered by other spirits and reduced to a skeleton, before being re-assembled using new body-parts specially adapted to perform the shaman’s duties (such as ‘new’ eyes to do what normal people cannot, and see into the other realities which surround our own). The shaman also needed to learn the sacrificial rituals necessary to appease the spirits – a detailed accumulation of knowledge taught by one generation of shamans to the next. The literature on shamanic initiations is very great, but useful overviews may be found in Vitebsky (1995: 59–63), Czaplicka (1914: 178– 90) and Shirokogorov (1935: 344–58).

We know little of the process by which Norse sorcerers gained their powers, though as we have seen in chapter 3 the written sources give us tantalising hints. While we shall not dwell on this aspect of shamanism here due to the relative lack of Scandinavian data, it is worth noting that what we have fits well with the circumpolar complex. In the Viking Age too we seem to have sorcerers passing on their skills to a younger generation, people going to be taught by specialists (often among the Sámi), knowledge passing in families, and magical skills revealed or conferred in dreams, trances and ecstatic experiences.

Equally important is the concept of different types of shamans, each with their own roles and functions, and the operation of these people alongside other forms of ritual specialist in the same communities. In Siberia, the different categories of shaman in the main cultural groups have been reviewed by Czaplicka (1914: 191–202). It is here we find the differing concepts such as ‘family’ and ‘professional’ shamans (among the Koryak), ecstatic shamans, shaman-prophets and incantation shamans (among the Chukchi), and the ‘white’ and ‘black’ shamans found among many of Siberian peoples. By way of example, we can focus on a few of the Siberian peoples and the tribes of the Canadian Northwest Coast.

Collectively, shamans among the Chukchi were known as enenilit, ‘those with spirits’. They could be both male and female, though the powers of women shamans were considered inferior. Up to one third or one quarter of the community were belived to possess some measure of shamanic abilities (Bogoraz 1904–9: 413–16). In other areas of Siberia the pattern was the opposite, and when Krasheninnikov visited Kamchatka in the eighteenth century he recorded that female shamans were the most common and also the most powerful (1764: 85).

The Siberian cultures in general afforded women a remarkably low status, even by the standards of historical inequality (Bogoraz’ descriptions of Chukchi women emphasise this especially, recording the frequency of female suicides due to the sheer hardship of their lives; 1904–9: ch. 18). In this context it is important to consider the fact of female shamans, which in many cases were considered more powerful and worthy of respect than their male equivalents. The shamanic calling clearly provided women with what Hutton has called “exceptional opportunities to undertake public roles” (2001: 109).

Chukchi shamans were of three primary types, each with a precise sphere of activity and summarised with a specific terminology:

•kalatkourgin, one who ‘communicates with spirits’

•hetolatirgin, one who is ‘looking into’ (i.e. clairvoyance, divination, seeking the hidden)

•ewganva-tirgin, one who ‘produces incantations’ (i.e. operative sorcery)

The shamans were paid, but unlike other Siberian peoples the ritual specialists of the Chukchi did not have their own, secret language (Bogoraz 1904–9: 417).

Just as we have seen in some of the Sámi sources, the practice of every household owning a drum was also found among the Chukchi, Koryak and Yukaghir (Czaplicka 1914: 170). The fact that one or more members of every family was capable of communication with the spirits, often through personal songs and drum rhythms, did not work against the presence of full shamans in the same communities. Some tasks could only be undertaken by those with this greater level of power, and in this way the entire community was bound together by the same relationship to the supernatural.

Their rituals were most often performed in darkness. In the light of the Norse and Sámi traditions it is interesting to note that assistants played a major role, sitting in a circle and helping the shaman achieve contact with other realities. As trance was achieved, the Chukchi described the shaman as ‘sinking back’ (Bogoraz 1904–9: 413, 441, 448). This is exactly the same term used of the volur in Voluspá and other Eddic poems.

The most common material items used were ‘charms’, a very broad group of objects that could take almost any form, united by their conceptualisation as the guardians of the shaman and the community. They often took the form of carved or cast figures, either in animal shape, anthropomorphic, or therianthropic. The Chukchi also used drums, and had a rich tradition of shamanic songs. Masks were also used, though not in the actual process of ‘shamanising’, for which dolls representing helping spirits were employed instead (ibid: 341–8, 356ff, 361f, 366f; a range of rituals is described in Bogoraz’ ch. 14).

The notion of sorcerous dualism was also a common feature of Siberian shamanism, the division of its rituals into ‘black’ and ‘white’ strands corresponding very broadly to positive and negative social functions. It is now often hard to tell to what degree the binary oppositions found in the early ethnographies genuinely reflected the practices of Siberian spirituality – the emphasis on good and evil, night and daytime, and so on – but this terminology of ritual is still in common anthropological use (e.g. Vitebksy 1995).

Fig. 5.7 Front and back view of a Yakut shaman’s costume (after Birket-Smith 1933: 30).

Among the Yakut, the male (aïy-oïuna) and female (aïyudagana) white shamans would undertake rituals to improve human fertility, to cleanse the waters of fishing grounds and generally to provide services to the community (Czaplicka 1914: 195; Fig. 5.7). Several observers recorded that the black shamans (abassy-oïuna) were only ‘professionally’ bad, and that this affiliation reflected no more than the fact that they gained their power from negotiations with the forces of evil and darkness, unlike the white shamans who did the opposite. Troshchanski (1902: iii), for example, noted that the black shamans helped people just as much as their white counterparts. In his division of seiðr into ‘black’ and ‘white’ forms, Strömbäck (1935: ch. 3) makes the same point that although the objectives of the former are almost exclusively concerned with the projection of misfortune, the rituals by which this was acheived seem little different from non-violent sorcery.

It was also clear that the among the Yakut the black sorcerers were regarded as far more powerful than the white. Both kinds of shamans were also graded as to the skills they could master, with three levels of competence (Sieroszewski 1896: 628). Among the Buryat were found shamans who had inherited their powers and those of the first generation, also ‘real’ and ‘false’ shamans, and white and black sorcerers. The Votyak had ‘permanent’ and ‘temporary’ shamans, while the Samoyeds seem to have made no distinctions at all among their ritual specialists. In some places the balance between the different kinds of shamans shifted, and Czaplicka noted that by the early years of the twentieth century the Yakut had almost no white sorcerers left, while among the Votyak the pattern was the reverse (1914: 194f).

Alongside all these types of shamans, there were also other types of ritual specialist. The Yakut, for example, had individuals called aptah-kisi, whose role was tell special kinds of stories, relating the spiritual relationships of the community and its shamans. The Altai people had four kinds of specialists beyond the kam shamans (Czaplicka 1914: 200):

•rynchi, ‘who, during attacks accompanied by pain, could foretell the future’

•telgochi, ‘guessers’

•yarinchi, ‘those who can divine by means of shoulder-blade bones’

•yadachi, ‘those who can control the weather by means of a stone’

The work of Caroline Humphrey in this field has already been mentioned above, but we can also take up the example of Nepalese spiritual practitioners, dominated by two different types who have been termed shamans and lineage mediums, each with their respective spheres of influence, which are in turn linked to spatial perceptions (Walter 2001).

There are obvious points of comparison between the Siberian ritual specialists and the long terminologies of sorcerers that we have encountered among the Norse and Sámi. Scandinavian sorcery is seen in a new light, and the patterns observed there appear typical of the circumpolar region, rather than as curious Viking-Age anomalies. Strömbäck was especially interested in the notion of black and white shamanism, and its applicability to the interpretation of seiðr (1935: ch. 3). Here he interpreted ‘divinatory seiðr’ as the counterpart to Siberian white sorcery, and most other forms as typifying ‘black seiðr’ – the latter with special reference to the abilities of Óðinn.

As we have seen, the Norse and Sámi sources also contain several references to special physical qualities possessed by sorcerers, especially curious aspects of their appearance. The same pattern is found in Siberia, and was recorded by a number of ethnographers independently of each other. A typical example is found in Sieroszewski’s description of a sixty-year-old Yakut shaman called Tiuspiut (‘Fallen From The Sky’), who had gained his powers in his early thirties and even in his advanced years was said to be thin, muscular and with immense stamina that enabled him to dance his rituals for an entire night:

During the shamanistic ceremonies his eyes had a strange expression of madness, and a pertinacious stare, which provoked to anger and excitement those on whom his look rested. This is the second shaman with such strange eyes whom I have met in the district of Yakut. Generally in the features of a shaman there is something peculiar which enabled me, after a short experience, to distinguish them from the other folk present.

Sieroszewski 1896: 396

Almost exactly the same was recorded by Bogoraz during his work with the Chukchi for the Jesup expedition, but he also noted what the people themselves thought about it:

The eyes of a shaman have a look different from that of other people, and they explain it by the assertion that the eyes of the shaman are very bright (nikeraqen), which, by the way, gives them the ability to see ‘spirits’ even in the dark. It is certainly a fact that the expression of a shaman is peculiar … and it is often possible to pick him out from among many others.

Bogoraz 1904–9: 116

Other writers referred to these qualities again and again, often commenting on the generally unsettling nature of the shamans right across Siberia – that they were people in whose presence it was difficult to be comfortable, whose glance was best avoided, even that they possessed a strangely disturbing beauty. It is easy, of course, to suspect a degree of suppressed homoeroticism in the responses of some of the male Europeans who came to Siberia from a very different world, but this cannot account for more than a small proportion of the descriptions. We should think here of the sharp teeth of the Sámi shamans, and there is also a parallel in the sagas.

In chapter 3 we have already mentioned Gunnarr Hámundarson being seen sitting happily in his barrow, in Njáls saga 78. Several people have nocturnal visions of the mound opening, while Gunnarr sits inside and turns towards the moon. This may be an important element of the scene, as the effect of moonlight on the faces of the undead is a curious and unexplained theme in several of the sagas with supernatural elements. A good example is the unsettling episode in Grettis saga (35), when at the moment of death the revenant killer Glamr stares up at the moon with an expression that is declared by Grettir to be ‘the only sight he ever saw which frightened him’. These episodes may be purely for dramatic effect, but the focus on their eyes is remarkable nonetheless.

Just as elsewhere in the circumpolar belt, on the Northwest Coast the various nations also possessed different types of ritual specialist, including several forms of shaman, adapted to the needs of the community and specific environmental contingencies. With slight variation from people to people, three main categories of shaman can be distinguished, each with appropriate functions:

•Curing shamans

○ helped the sick and fought for the recovery of lost or stolen souls

○ often fought the effects of evil shamans and ‘witches’

○ could make a diagnosis, and then decide whether to proceed based upon the risk involved to the shaman

○ characterised by extensive material culture for use in the rituals, especially rattles

• Fishing shamans

○ ensure continued cycle of spawning and migration for the fish in the coastal rivers

○ special function of welcoming the ‘First Salmon’, to encourage the fish to return each year

○ characterised by extensive material culture for use in the rituals

○ surrounded by a great many myths and ancestral narratives

• War shamans

○ forecast the outcome of battle, and determined favourable circumstances for its prosecution

○ made predictions about violent events through divination rituals

○ could control the weather

In addition to the specific functions listed above, the shamans could also generally attract game, see events happening far away, and predict the future. We may also add a fourth category of Witches, specialising in destructive sorcery and the infliction of harm (for a Tsimshian example, see the ‘Witchcraft narrative’ recorded at Giludzao, in Cove & MacDonald 1987: 153ff). In their relationship both to the shamans proper and to society in general, the ‘witches’ of the Northwest Coast have many parallels with the ilisitsut of the Inuit (Merkur 1987) and the yenaldloshi, the so-called Navajo Wolves or ‘skinwalkers’ of the American Southwest (Kluckhohn 1994). Similar points of comparison may be made with the aggressive sorcery of the Chukchi (see below, and Bogoraz 1904–9). We should remember in this context the category of specific and derogatory ‘witch’ terms in the Old Norse sources.

Northwest Coast shamans could be male or female, though the former tended to predominate. We see again the familiar pattern of spiritual power received, often involuntarily, either in dreams or through encounters with supernatural beings (Figs 5.8 & 5.9). Among the Haida, long-dead shamans could choose their successors, speaking to them from the spirit world, and preparing them by ‘making a hole in their minds’ (Swanton 1905: 311, in ‘Story of the shaman, G.a’ndox’s father’). Shamans served apprenticeships, and were in part elected by their communities. Unlike many of the Siberian cultures, on the Northwest Coast the role of shaman could be seen as actively attractive – there are even stories of small children playing at being shamans, ‘curing’ each other and so on (Cove & MacDonald 1987: 113, ‘Shaman’s narrative’; see also the Haida tales of shamans collected in Bringhurst 1999, 2000, 2001).

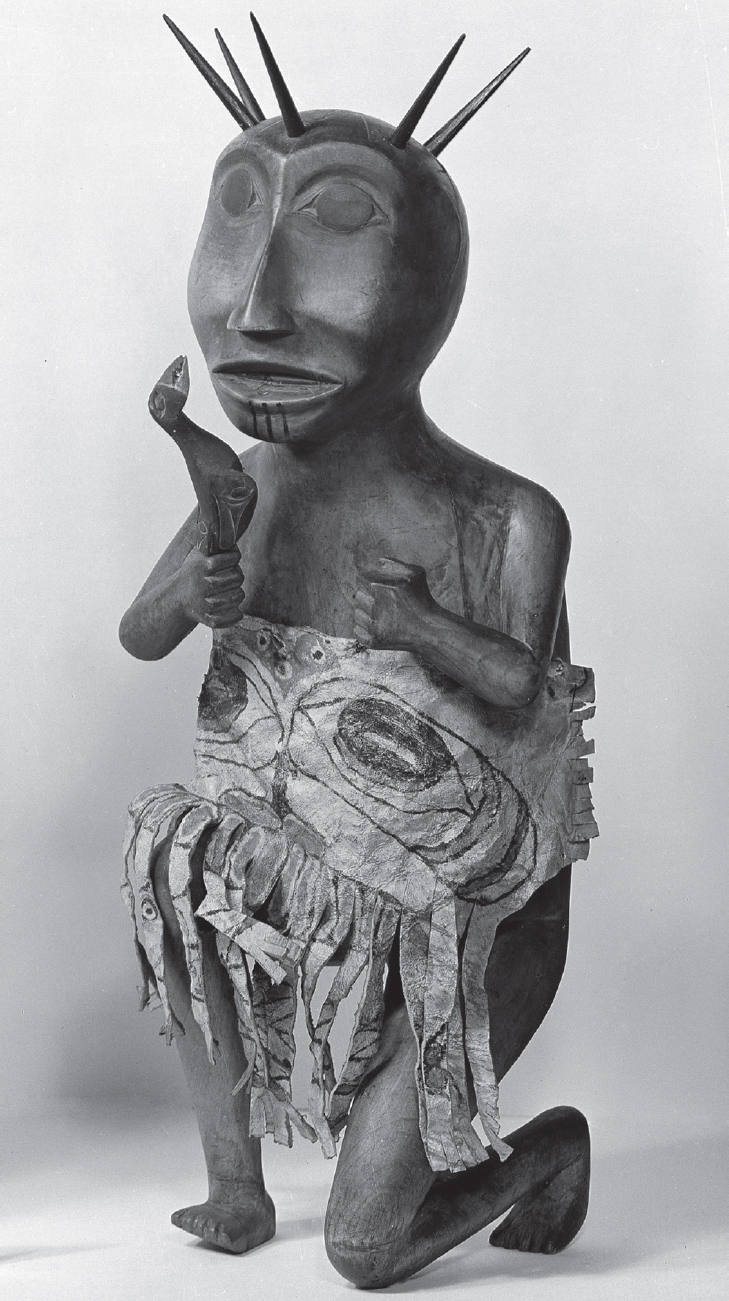

Fig. 5.8 Carved figure of a shaman from Haida Gwaai (photo Wellcome Trust, Creative Commons).

Their special equipment took various forms, but most often centred on bearskin robes, aprons of leather and blankets decorated with totem animals, and ‘crowns’ of grizzly bear claws; some female shamans used labrets (lip ornaments). We also find very elaborate necklaces of claws and deer horns, the penis bones of bears (a striking parallel to the Sámi drum amulets here) and various charms made of animal bone, fur and skin (Fig. 5.10). Animal body parts, such as deer hooves used to form a hanging fringe on a robe, were employed to gain the strength or agility of the animal in question. Painted designs on clothing were oriented so as to be seen best by the wearer rather than an observer, serving as sources of power and inspiration for the shaman, a link with his or her totem animals (Rockwell 1991; Wardwell 1996: 164–216, 282–98; Ruddell 1995: 46).

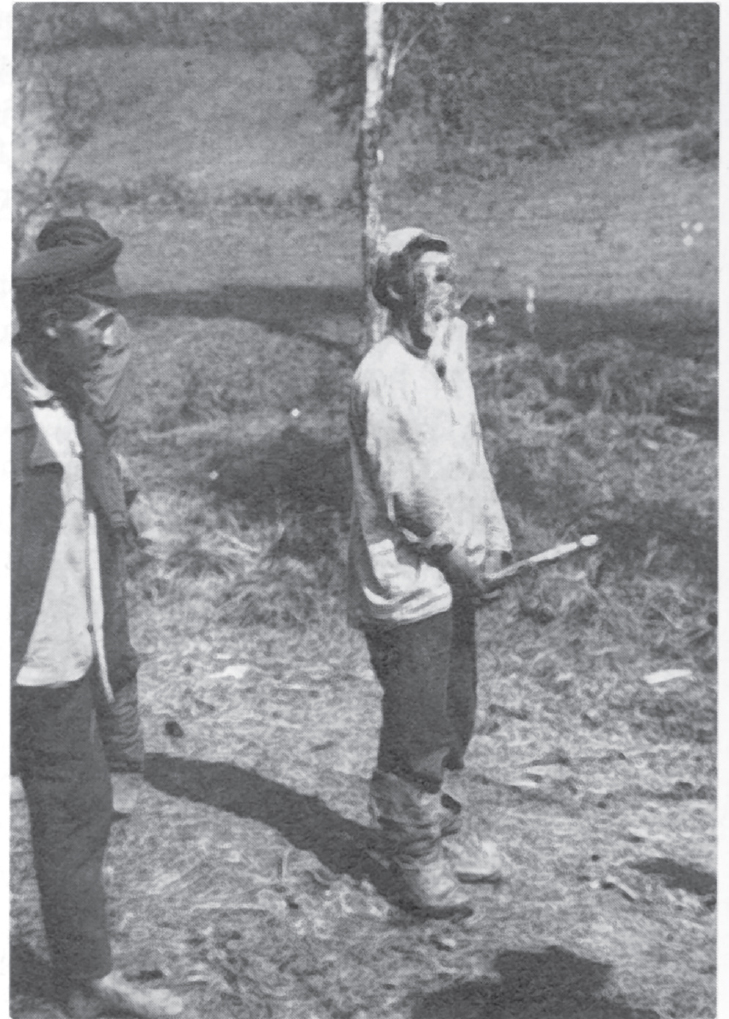

Fig. 5.9 A female shaman from Kispiox village, Haida Gwaai (after Cove & MacDonald 1987: 108; photo G. T. Emmons).

Fig. 5.10 Ritual paraphernalia collected from a Sheena River shaman (after Cove & MacDonald 1987: 125; photo Field Museum, Chicago).

Northwest Coast shamans used drums, rattles, dolls, sucking tubes to draw out or inject sickness and evil, and a large array of charms. Cutting instruments were also common, as were miniature means of transport such as small wooden canoes, which would help the shaman travel to other worlds. They also wore masks, though not usually while performing shamanic ritual (this especially applies to the Tsimshian and Haida). Many shamans also carried a staff, of special interest in the light of the Nordic staffs (Fig. 5.11). Made of wood and varying in size from about a metre to approximately shoulder-high, the staffs were made of wood and served as symbols of authority. Usually very slim, most of those that survive today are either undecorated or very simply ornamented with carvings of spirit helpers. The primary symbolic dimension of the staff was as a metaphor for the world axis, the Cane-Of-The-Sky that as we have seen also appears on totem poles (Wardwell 1996: 218–80).

As we have seen among the Norse, the staff could also have other, more directly human overtones. This sexual symbolism was also an integral part of circumpolar ritual as it was among the Sámi and the Viking-Age Scandinavians, and similarly embedded within a complex network of gender constructions. We can now consider these, and their correspondences with the practitioners of seiðr.

To a Western public, the most startling aspect of the Jesup expedition’s reports concerned the clear evidence for what even then was described as a ‘third or neutral sex’ among the Siberians, in particular connected with shamanism. As part of the process of becoming a shaman, this recreation of the self that we have seen above, the individual often crossed the normally acceptable gender boundaries of his or her society, frequently taking on the dress or lifestyle of the opposite sex. This could be either temporary or permanent, and with varying degrees of impact on the sexual orientation of the shaman. The experience was often exceedingly traumatic, and responsible for a great many suicides.

These concepts were soon taken up in Western literature, especially works on homosexuality (eg. Westermarck 1909: 368f, 378f). One of the first subsequent studies of these gender constructions was in Czaplicka’s monograph on Aboriginal Siberia (1914: ch. 7), and the devotion of a whole chapter to the sexual aspects of shamanism placed the work far ahead of its time.

Among the classic examples of this from the early literature are the so-called ‘soft men’ of the Chukchi, described by Bogoraz (1904–9: 449–55, including his famous depiction of Tilu’wgi, a shaman of this kind). This term, which was the ethnographer’s translation from the Chukchi yirka-lául, was until relatively recently applied beyond Siberia as a category similar to the ‘berdaches’ of North America; these wider meanings have been much contested, and the use of ‘berdache’ in particular is now generally avoided as a perjorative (see Lang 1998: xi–xvii).

Fig. 5.11 Shamans’ staffs collected on the Skeena River in 1892 (after Cove & MacDonald 1987: 265; photo Field Museum, Chicago).

Among the Chukchi the process of ‘soft man being’, by which a shaman was transformed into a yirka-lául, was usually dreaded; some men preferred death to obeying the command of their spirits (Bogoraz 1904–9: 450). The transformation could take several forms, and a shaman did not always progress through all of them. The first was a change of hairstyle, from male to female fashion. This was adopted by shamans, but also occasionally by the sick, with the intention of confusing the spirits of illness who would mistake them for someone else. The second phase was the adoption of female dress, though male patterns of social behaviour were retained. The third phase involved the complete adoption of female habits, including sexual congress, cohabitation and marriage with men. All three types of yirka-lául retained their male names, but they acquired special spirits appropriate to their new gender identity (ibid: 450–2).

The ‘soft men’ were regarded as the most powerful of all, and Bogoraz observed that, “the people are extremely afraid of the transformed, much more so than of ordinary shamans” (1904–9: 451, 453). At the same time, they were hated and the objects of scorn, though this was never expressed to their faces for fear of the consequences. Hutton (2001: 109) has speculated that Bogoraz may here have been projecting his own homophobia onto Chukchi attitudes, but this combination of fear, repellence and respect is found in other shamanic cultures too and should not be lightly dismissed as a product of twentieth-century prejudice.

This notion of social extremity bringing with it an increase in shamanic power may also help to explain another aspect of the Old Norse descriptions of sorcery. As we have seen, there are numerous written accounts of Nordic peoples turning (or being forbidden to turn) to the Sámi for ritual help, and we should ask why they should need to if they had their own ‘shamans’. Here again we can find circumpolar parallels, as with Bogoraz’ observation (1904–9: 459) that the Chukchi regarded shamans from outside their own culture as being especially powerful, and that they were by preference consulted for particularly difficult tasks.

The shamans of transformed gender could also take a different guise. In very rare cases, a female equivalent to the ‘soft men’ was encountered among the Chukchi, though their existence has only been recorded secondhand. These women seem to have adopted only the third form of transformation, taking on male dress and behaviour, using spears and other weapons, and cohabiting sexually with women in the social role of a man. Bogoraz was told that they used sexual aids to simulate the male genitalia, emphasising how far the change of gender extended within this construction of shamanic identity (1904–9: 455f).

The same phenomenon of ‘soft men’ was found further south in Kamchatka. Steller wrote that almost every man among the Kamchadal (Itelmen) and the Koryak had a wife and a koyekchuch, a man who dressed and acted as a woman (1774: 289, 350). Another visitor to the region, Krashennikov (1819: 158), recorded the same term and behaviour, while nearly a century later Jochelson collected stories of them but found none still alive (1908: 52–3). Similar patterns were reported from the Kadyak islands by Saritchev (1811: 33), who had visited them as part of the Billings expedition. Unfortunately, with the exception of Jochelson all these writers focused their attention on the ‘shocking’ fact of the same-sex relationships rather than any spiritual dimension to them, so it is uncertain to what extent they were reflections of shamanic power.

In his work with the Yukaghirs, Jochelson found nothing resembling a category of transformed shamans, but he did encounter male shamans who dressed in female attire (1926: 193ff). A similar phenomenon was recorded by Sieroszewski among the Yakut (Sakha), where he interpreted it in the light of the great respect afforded to female shamans (1896: 631). Jochelson thought that both examples could be seen as an inland echo of the Chukchi’s ‘soft men’ in the east, something resembling the second phase of ‘soft man being’. It may be significant however that the Yukaghir and Sakha did not regard these ‘cross-dressing’ shamans as in any way different, unlike the Chukchi for whom the yirkalául was something very specific. Later traces of the same phenomenon have been found in central Asia by Basilov (1978), with distant echoes among the Khanty (Balzer 1981).

Several overviews have appeared on this subject (e.g. Balzer 1996, Ripinsky-Naxon 1997), and the history of research into an engendered understanding of shamanism has been surveyed by Sandra Hollimon (2001: 124– 7). In addition to the ecstatic states of consciousness and the mastery of spirits focused upon by Eliade and Hultkrantz, Hollimon adds a new element to the definitions of circumpolar rituals by proposing that a key aspect of shamanism is “the experience of manipulating the supernatural power, especially that perceived to be housed in sexual energy” (ibid: 124).

In arriving at this conclusion, Hollimon’s primary point of comparison with the Siberian material is with the multiple genders associated with the indigenous North American religions. The standard work in this field is Sabine Lang’s 1998 study Men as women, women as men, which gathers all the main research. The study of the so-called ‘berdaches’ of the Native Americans is a vast topic which cannot be discussed at any length here, but both Lang and Hollimon review a very large spectrum of tribal examples of third and fourth gender shamanic figures to which the reader is referred (see also Roscoe 1987 and 1999; these concepts have important continuities to modern Native American sexual perceptions of ‘changing ones’ and ‘two-spirit people’, which go beyond the Western conventions of hetero- and homosexuality).

In the present context we can merely note the ubiquity of such liminal concepts in North American spiritual practices, with the same affinities to the Siberian ethnographic record as we find in the cosmology. We also find a range of transformation myths, and common mediating spirits of bears and ravens – again, as in Siberia and Scandinavia.

The concept of the shamanic gender reaches its probably most developed form among the Inuit, where it has also been amongst the most extensively studied. The leading scholar in this field is Bernard Saladin d’Anglure, who has explored the sexual aspects of Inuit spirituality in a number of crucial papers (e.g. 1986, 1988, 1989, 1992a–c, 2001; see also Taylor 1989 for a case study of sexual shamanism among the Labrador Inuit). As this work has shown, not only is sexuality the defining theme in Inuit ritual, but the role of the shaman is such that it constitutes a third gender in itself, alongside that of ‘woman’ and ‘man’. This echoes the earlier conclusions of Czaplicka for Siberian religion, that “socially, the shaman does not belong to either the class of males or to that of females, but to a third class, that of shamans” (1914: 253). As with the Sámi, much of Inuit sexuality and spiritual power is connected with the unborn soul, and the complex rituals whereby names and identities are conferred in the specific temporal, geographical, seasonal and cosmological circumstances of birth. Building on many years of his own fieldwork and that of others, especially Knud Rasmussen, Saladin d’Anglure has focused on the notion of sexual relations between shamans and the spirit world, a subject to which we shall return in other contexts below.

Once again, there are obvious parallels between all these gender identities and the complex of sexual restrictions that surrounded Norse sorcery in the Viking Age. Along with the network of ergi-related practices and the men who took on such associations, we can also think of the various elements of the human soul, and their importance for the performance of seiðr. As a contemporary coda to this, it is worth also looking to pagan Anglo-Saxon England, and the evidence for similar gender constructions as postulated from graves (Knüsel & Ripley 2000, with an excellent discussion and analysis of grave-goods that expands considerably on the data presented in Wilson 1992).

Thus far we have considered the sexual identity of shamans in the circumpolar area, but not the explicitly sexual aspects of the rituals themselves, of the kind that we have observed in connection with seiðr.

We can focus here on two forms – sexual components of the rituals, and sexual dimensions of shamanhood itself, expressed particularly in an erotic bond between shamans and their attendant spirits or other supernatural entities.

In many parts of the circumpolar region, as for the Norse, it is clear that almost every aspect of the shamanic ritual could be infused with more or less explicit sexuality. In some instances, these sexual overtones were fundamental to the nature of the performance. Pentikäinen has also stressed this point, with reference to what he calls the ‘bodylore’ of shamanism (1998: 53). He gives an example of such a sexual performance from a Selkup shamanka named Salda, in which he translates Anutshin’s 1914 account of the chant sung in the Kaljagino district of Siberia, west of the Yenisei river. The shamaness is dancing (‘…’ in the text below indicates physical movement in between the spoken words) inside a firelit ring of onlookers, of mixed sex and age:

Men and women, have a look at what old Salda is doing … Boys and girls, have a look …

Am I a stranger to you? …

No, I’m your mother …

I’ve been living a long time …

I’ve been feeding many people: some are alive, some are dead …

Give something to the old Salda, she will be dancing well … She has always been dancing well …

Hey, men, give me some vodka …

Hey, women, throw some logs into the fire …

[The audience give her vodka and build up the fire. When the shamanka drinks the vodka, she screams and begins to jump wildly about, holding her breasts]

Burn brightly, fire …

The fire is hot, the smoke is bitter …

The coitus is sweet, but giving birth is bitter …

The front is hot from the fire, the back is cold from the wind …

The front is hot from the man, the back is cold\ from the ground …

The bird’s got a lot of brain, the bear’s got a lot of brain … Why am I not a bird, why am I not a bear? …

Every night the sun goes into the earth and comes out … My old man was a good worker, my old man was like the sun …

Don’t you remember him, aren’t you his children? …

My old man was hot on top to make Salda hot …

He was doing like this and I was doing like that …

[She mimes sexual actions]

Now the old man has gone, and I have become like a frozen ground …

Hey you, still having sex, why are you sitting? …

Come here, let’s dance together …

[She repeats her appeals and some of the older women begin to dance. The younger members of the audience remain sitting, and discuss the behaviour of the old shamanka. Salda continues to more frenziedly mime sexual acts]

If my vulva had teeth, it would bite off the penis so that it could remain there forever.

[The dance and sexually suggestive activities continue until sunrise]

Pentikäinen 1998: 53–6 after Anutshin 1914; parenthesised explanations added

Among the Chukchi there was also a special category of sorcery with sexual objectives, usually performed by women against a female rival for a man’s affections. Some of these involved projected transformations into animal form, for example in a charm to change the rival into carrion and the man into a bear, which would then eat the carrion and vomit it up, utterly destroying the victim. Men could also perform such rituals to attract women; the sources emphasise the role of saliva as the medium of the charm, which was effected by spitting it onto the target (Bogoraz 1904–9: 478, 507f).

Similar tales are told on the Canadian Northwest Coast, of shamans using their powers to obtain sexual favours. Sometimes this is in the form of more straightforward courtship, while at other times deception is involved, as for example in the Tsimshian story of the Trickster figure Txamsem, who poses as a shaman whose penis will ‘cure’ a sick girl. Another common pattern is for a shaman to inflict illness in his chosen partner, and then demand her sexual compliance as the price of curing her (see the stories ‘Txamsem seduces a young woman’, ‘Shaman’s narrative, ‘The narrative of Tsak’ – Cove & MacDonald 1987: 31f, 113–7, 126–31).

These associations could also be reflected on the shaman’s equipment. Some Siberian shamanic costumes included depictions of the wearer’s sexual organs, as a sign of his or her power; sometimes the genitals of both sexes were shown, which is thought to have symbolised the change of gender (Nioradze 1925: 70). The paraphernalia of Northwest Coast shamanism also included a great many phallic and vulvic images (see Duff 1975: 48f, 84, 92f, 98, 114–22, 127).

An association is also seen between shamanic skill and sexual prowess, for example among the Teleut of southern Siberia. As the shaman climbs a pole representing the tree connecting the worlds, at a certain stage he begins to sing a sexually-explicit chant referring to his genital organs, intended to strengthen the potency of the community’s men (Zelenin 1928: 91). In a similar context in the Tomsk region of Siberia, the shamanic horse sacrifices of the Kumandin included a performance by three masked men who ‘galloped’ around carrying large wooden phalli between their legs, with which they touched spectators; all the while erotic songs were sung (Zelenin 1928). A similar ritual was observed by N. P. Dyrenkova in 1927, among the Shoor people whose territory borders on that of the Teleut (Fig. 5.12).

The work of Saladin d’Anglure among the Inuit has been mentioned above, and the complex system of erotic dreams and sexual relations between shamans and their spirit assistants. Many Siberian shamans also had a sexual relationship with one or more of their helping spirits, and sometimes chose a ‘wife’ or ‘husband’ from among them (see Eliade 1989: 71–81). An example of this is recorded by Sternberg (1925: 475–8), in a detailed description given by a shaman of the Goldi people from the Amur region. By his account, the ajami (tutelary spirit) of his ancestors forced herself upon him sexually, thereby entering into a kind of marriage with him. Over the many years that this continued, the spirit granted him gradually increasing powers of shamanship and the services of a number of syvén helping spirits. Sternberg also noted that the trance in which the shaman communicated with his ayami was itself highly erotic in its nature, with suggestive movements and sounds. Similar associations were noted by Shirokogorov when he participated in a prolonged election ceremony for a female shaman of the Manchu people (1935: 351–8), and he relates how the young woman experienced feelings of sexual arousal during her possession by the spirits who had come to decide whether she should proceed as a shaman. Despite this, Shirokogorov was sceptical to Sternberg’s location of sexuality as one of the roots of Siberian shamanism, and instead argued that it was but one component among several (1935: 366–8).

Fig. 5.12 A masked man holds a wooden phallus during a shamanic ritual offered to the deity Kotshagan by the Shoor people of southern Siberia (after Pentikäinen 1998: 54; photographed in 1927 by N. P. Dyrenkova).

Moreover, sexual congress with a spirit did not always confer shamanic powers on a human being. Among the Yakut, human-spirit marriages occur both in folklore (Eliade 1989: 73), and in the documented ethnographic past, with descriptions of abassy spirits seducing similarly unwilling young people of either sex in their sleep (Sternberg 1925: 482). In most cases these encounters resulted in a general feeling of well-being, occasionally in life-long celibacy or a disruption to the individual’s sexual life, and only in a minority of cases led to an acceptance of shamanhood.

Among the Teleut by contrast, human-spirit marriages were far more closely associated with the activities of the shaman (Sternberg 1925: 487). The Chukchi elevated this to a very public level, and Bogoraz describes how some shamans would arrange an annual or bi-annual ceremony during which they would appear naked, speak incantations over their genitals and address them to their helping spirits, thereby cementing the sexual bond between for a further period (1904–9: 449). These spirits were sometimes thought of as ‘wives’ and sometimes simply as sexual partners, though the distinction was somewhat blurred in Chukchi society which as we have seen afforded women a status scarcely better than slaves. At the same time as the Chukchi shaman could have one or more spirit wives, he could also take a human partner. Bogoraz was told how the faces of the spirit wives would watch the shaman from the walls and shadows of his dwelling, never giving his mortal wife peace. The Chukchi ‘soft men’ could take spirit husbands in the same way (ibid: 452ff).

We can isolate a number of common factors in the sexual elements of circumpolar shamanism:

•sexual relations between a shaman and his or her tutelary spirit(s) may be of various kinds, most often against the will of the shaman, and may include a form of marriage between the two

•such relations may result in the acquisition of additional powers, but are not fundamental to operation as a shaman; many shamans do not experience them

•such sexual relations may also occur between spirits and individuals who are not shamans

•sexual elements in shamanic rituals do not relate solely to the relationship between the shaman and his or her spirits, but also concern the broader fertility and sexual health of the community

Without venturing beyond the scope of the present work, we can merely note here that similar erotic components to those found in circumpolar ritual are also encountered in comparable shamanic belief systems in other parts of the world (e.g. Lewis 1989: 51, 57, 131; Vitebsky 1995: 56, 80).

From this sexual complex we can move to the other pole of sorcery as we have observed it in the Norse and Sámi worlds – that of magic used for violent or aggressive ends. This too has a wide range of circumpolar parallels.

Rituals for aggressive purposes were also a frequent feature of circumpolar practices (Fig. 5.13). Just as in Sámi society, the same categories of ‘good’ and ‘evil’ shamanic specialists were found in Siberia, though less detailed records have survived. Bogoraz noted two types among the Chukchi:

•kurg-ene’nilit ‘mocking’ shamans, with negative connotations

•ten-čimnulm ‘well-minded’ shamans, with positive connotations

They were also conceptualised in terms of colour symbolism, with the classic black and white shamans of the early Soviet ethnographies here rendered as respectively black and red. Their behaviour was also similar to that of the noaidi: for example, Bogoraz describes the eating of souls by Chukchi shamans in the same manner as we have seen among the borå-noaidi of the Sámi (1904–9: 430ff, 465).

Warfare among the Chukchi was conducted with an advanced array of equipment – complex bows, special lances and fighting knives, and suits of armour made from overlapping iron plates and strips (Bogoraz 1904–9: 151– 68). It mostly took place at the level of low-scale combat or individual duels, and often involved ambushes or night attacks on sleeping camps (ibid: 639–42, 645). Chukchi war ‘sagas’ are also recorded, detailing larger-scale conflicts with the Cossacks, Eskimo, Tungus and Yukaghir peoples. In all of this, great emphasis was placed on individual combat and agility, through a complex network of associations between violence, strength and masculinity.

The role played by shamans in fighting was very prominent, and also a matter of honour. It was considered important to avenge attacks by enemy shamans as soon as possible (Bogoraz 1904–9: 483). The violent context of Chukchi shamanism can be seen in some of the alternative words for shamans, as they were described as being ‘resistant to death’ and ‘difficult to kill’ (ibid: 417).

One principle above all runs as a constant in Chukchi war sorcery, “the artificial creations, which are materialised, and then sent to destroy the enemy” (Bogoraz 1904–9: 481). This same idea of the projection of destruction is also found among the Inuit of Baffin Island (Boas 1901: 153, 363). Aggressive sorcery formed a category in its own right, called ui’wel. There were two types:

•oiwa’chirg-ê’wgan ‘spell incantations’

•a’n^nêna-ê’wgan ‘anger incantations’

Women specialised in these war charms, and in the now-familiar pattern there were also women whose sorcery worked as a protection against them. These took a physical form, as something summoned (or sometimes actually created) and then unleashed against the victim, who was said to be ‘doomed to anger’.

Fig. 5.13 Shamanism as aggression: a Mongolian shaman in trance, photographed in 1934. Note the locked facial muscles, and the eyes rolled back; the orignal was captioned by the photographer, “raving shaman” (after Forbáth & Geleta 1936).

The charms took the form of one or more spirit-animals, monsters, spirit-men or -women, or inanimate objects such as a stone or a tree. Sometimes just parts of an animal would be summoned: the upper half of a seal, the head of a fox. Some victims would go insane at the sight of such horrors; others were deceived into thinking that the spirit animals were real, and in trying to hunt them would be lured by the spirits out onto thin ice, or would otherwise die in an attempt to kill them. All of the animal spirits of this kind were associated with the ability to cause intense pain, and their purpose was primarily to torment their targets (Bogoraz 1904–9: 482f)

The summoned, or ‘materialised’ in the translation of the Chukchi term, creatures would attack the victim, and if successful, then either return to their sender or disintegrate having fulfilled their mission. It was very important that once summoned, the spirit be unleashed immediately for fear of harming the summoner. A powerful shaman could ‘catch’ such creatures and restrain them; ashamed of their failure, the spirits would then insist on being sent against their sender, to revenge themselves on the shaman who had sent them into a trap.

The charms necessary to send such creatures were mostly performed by shamans, but could also be taught to others, called hiule’t-re’mkin, ‘knowing people’, another of these additional categories of ritual specialist. The charms could also be inherited at the death of their ‘owner’, or bought (Bogoraz 1904–9: 471f).

These spirits could also serve other purposes than simple attack. For example, a special class of them were known as chi’chin, ‘looking ones’, and employed as scouts to spy out terrain and enemy troops before a physical assault. There is an obvious parallel with the gandir and fylgjur that, as we have seen, in certain circumstances went ahead of an attack in Viking sorcery.

Animal transformation also played a prominent part in the imagery of Siberian aggressive sorcery. Spirit attacks might begin, for example, with the ‘Raven Incantation’, which a shaman would use to gain the power to hurt his enemies. The shaman’s knife would become the beak of the raven, ready to peck his foes (Bogoraz 1904–9: 508). Bogoraz collected several very detailed stories of spirit attacks on shamans, and it is interesting that among the Chukchi the dead themselves were considered to be enemy spirits (ibid: 417, 517ff).

The attack charms themselves were even more complex. Thus a victim’s spirit might be transformed into a seal-skin, which would then be consumed by spirit-shrimps summoned from the sea by the shaman. Alternatively, a victim might be symbolically wrung through a net into a pot, in the same manner as one strained half-digested moss from a reindeer stomach. The pot would be buried and covered with a bird’s wing, after which its contents would be transformed into a dog, which would wander lost from camp to camp. The same spell could create a dog of destruction, unleashed by the shaman on his enemies. A particularly terrible set of charms involved acts of cannibalism, in which the shaman in raven form pecked at a fresh corpse, representing his enemy. The nocturnal activities of this kind that shamans performed in burial grounds contributed to the terrified awe in which they were held. Other spells, called ei’ut, were used to hinder an enemy or slow him down; they could also slow the dead, and thus bring them back to the world of the living (Bogoraz 1904–9: 480).

Variants of all these forms of aggressive sorcery were also found among the shamans of the Aleut, as was observed on the Billings expedition of the late eighteenth century (Saritchev 1802: 142).

As with the Chukchi raven-charm, it was also possible for a shaman to transform himself into a wolf to attack his enemies, having first smeared his mouth with fresh blood to symbolise the coming kill (Bogoraz 1904–9: 481). Similar imagery is found in Palaeo-Eskimo shamanism in the Canadian High Arctic, with excavated material from the period AD 500–1000 including human-wolf transformation figures. Especially striking are sets of wolf’s teeth carved out of ivory, designed to be held under the upper lip to provide the wearer with lupine fangs (Sutherland 2001: 138f).

A crucial element in eastern Siberian war sorcery was first identified among the Koryak, in the form of objects that had been imbued with power through special rituals; the Koryak word for them meant simply ‘things enchanted’ (Jochelson 1908: 32). The charms were believed to be a form of interaction between the shaman and the vital principle contained within the object, essentially the ‘soul’ of the weapon or whatever else was to be made an instrument of shamanic aggression. Bogoraz (1904–9: 469f) noted the same phenomenon among the Chukchi, where one could go to a shaman to ‘purchase’ a charm to say over one’s weapons. These charms could wear out, and after a time it was necessary to buy new ones to replace them. The act of fastening the charm to the object required great skill, and was fixed by the application of a shaman’s saliva.

Clearly, the shamans were thought to wield potentially immense powers of destruction. If a Chukchi shaman became known for causing too much harm in a district, his neighbours or the community sometimes acted collectively to kill him, employing special means which have not been recorded (Gondatti 1898).

Outside the sphere of warfare, there were variants of the charms that could be applied to bring luck in hunting or fishing, in the sense of these activities as an ‘attack’ on the animals concerned. Men performed the charms for hunting game, while women performed those for marine creatures. These latter rituals were performed at home, as the women charmed the seals, walrus and fish close to the shore where the men could catch them (Bogoraz 1904–9: 470). Some of the charms were very specific, for example for trapping wild reindeer as they crossed a river, whereas others were for general-purpose hunting. Of a related kind were charms for controlling the weather during the hunt, by subduing snowstorms or ‘tying up’ the wind (ibid: 496ff).

In the circumpolar shamanic cultures, it is not unusual to encounter actual defensive structures built in the ‘other world’ and intended to play a part in the spiritual combat that formed another dimension of ‘real’ fighting. For example, among the Evenki we find special breastworks of wooden stakes, marylya, set up around the boundaries of the spiritual space occupied by the clan, and guarded by shamanic beings (Anisimov 1963: 110; cf. Tolley 1995a: 66); the fences, which ‘exist’ only in the spirit world, are visible only to shamans. This concept of bounded space, including an aspect related to aggression and the defence of boundaries, is also found among the Khanty (Jordan 2001a and b) amongst other Siberian peoples.

We see similar patterns of violent sorcery on the Canadian Northwest Coast, where the ability to inflict harm must be seen as one of the most central aspects of shamanism. For example, a Tsimshian narrative about the great shaman Sqenu describes the moment when as a young boy he gains his first powers; wanting to see whether he really is becoming a shaman, the boy immediately tries to inflict various forms of damage – killing a seagull, crippling a man, and causing illness. It says much that his reputation as one of the most famous of shamans was built up by first making people sick, and then using his powers to cure them, in the process extorting vast sums of wealth as payment for the healing ritual. This is judged to be praiseworthy behaviour (Cove & MacDonald 1987: 113–7, ‘Shaman’s narrative’).

On the Canadian Northwest coast, a common form of spiritual attack was to use witchcraft to steal a person’s soul, and to then fill the empty body with evil spirits summoned for the purpose. To counter this, shamans used special soul-catchers to retrieve the errant soul and restore it to the body. Often made from the hollowed leg-bones of bears, these objects were highly prized and were sometimes carved in the form of a double-headed animal (Kirby et al. 1995; Wardwell 1996: 196–204). The soul was thought to be very fragile, and there are tales of shamans who had retrieved them being carried very carefully because to walk by themselves would damage the soul (Swanton 1905: 311, in the ‘Story of the shaman, G.a’ndox’s father’). Along with other objects of power, the soul catchers were stored in special cedar boxes – a kind of shamanic ‘tool box’ – to conserve their energy and to prevent others from being harmed by it.

Combat between shamans, the classic duelling described in preceding chapters, was also common on the Northwest Coast. Using special weapons, usually ‘different’ in some way – perhaps broken, or daggers made of wood, or miniature carvings of blades – shamans would fight in spirit-form in their dreams (Kirby et al. 1995). In considering these special weapons we should perhaps remember the broken-pointed knife owned by the volva in Eiríks saga rauða.

Other tools used for shamanic duelling included bone head-scratchers, which could inflict projected injury on an opponent through their absorption of the potency contained in the hair. Shamans habitually kept the scratchers tucked into their hair, recharging their power to be available when required. Some of the greatest shamans, such as the Haida Kudé, grew their hair in waist-length dreadlocks as a symbol of their terrible power (Lillard 1981: 169; MacDonald 1996: 188f).

These conflicts could be epic in scope. The Tsimshian story of the Squirrel Shaman of Gitwansilk involves the deaths of two entire villages as two rival shamans fight in different guises, a battle that continues even beyond their deaths (Cove & MacDonald 1987: 132ff); the episode was commemorated in the totem pole of the victorious shaman’s home village, now on display at the CMC in Gatineau. Duels could take place at famous landmarks, at man-made structures like bridges, and could continue underground or in the undersea worlds (for more stories of Tsimshian shamanic duels, see Cove & MacDonald 1987: 135–9).

Warfare was a major feature of life on the Northwest Coast – a significant difference by comparison with the Sámi but interesting in relation to the Norse. It was conducted over territorial disputes or conflicts over access to hunting and fishing resources, but also for specifically religious purposes. Sometimes quite large military expeditions were mounted to obtain ritual prerogatives, such as the right to wear certain masks in the important potlatch ceremonies. Important collections of war stories have been recorded among the Haida (Swanton 1905: 364–448), the Tsimshian (MacDonald & Cove 1987) and the other coastal peoples. Shamans played a prominent role in this kind of fighting, and preserved wooden weapons from the last two centuries or so are often decorated with painted spiritual designs. A Tlingit myth about a war between the Kā’gwantān and the Łuqā’xadî provides a good example of shamanic combat:

At that time there were two canoe loads of Island [Łuqā’xadî] people going along, and there was a shaman among them named Wolf-Weasel, who had eight tongues. The Kā’gwantān shaman tore his canoe apart by pretending to split the water of its wake. Before they got far out it began to split. The Kā’gwantān warriors had already landed at Xuq! creek where this shaman also went ashore, and they came out behind him. His spirits’ apparel was in a box in the bow.

When the warriors rushed down upon them they soon destroyed his canoe men, but the shaman himself flew away by means of his spirits. Even now people say that a shaman can fly about. After he had flown about a certain town for some time the people told a menstruant woman to look at him. She did so, and he fell into a small lake. Then he swam under a rock, sticking up by it, leaving his buttocks protruding. To the present time this lake is red. It is his blood.

The sister and aunt of this shaman were enslaved, and the warriors also carried away his spirit box. Before they had gotten very far off, however, they stopped, untied the box, and began to handle the things in it. They took out all of the spirits [i.e. masks, whistles, etc], and asked his sister regarding one of them, “What is its name?”. This was the chief spirit, and had a long switch of hair. Then the warrior in the bow put it on saying, “Let me be named Hanging-Down Spirit”. Immediately he fell down as if he had been knocked over. He ceased to breathe. Another put it on. “Let me be named Hanging-Down Spirit”, he said. All of those who put this on were destroyed. One, however, stood up, made a noise, and ran off. To this day his [i.e. the shaman’s] spirit has not ceased killing.

From ‘Story of the Kā’gwantān’; original text (not quoted here) and translation from Swanton 1909: 337ff

Many of these elements will be familiar from both Norse and Sámi contexts: sorcerers fighting each other as part of larger military parties; the decisive importance of sexual elements (the menstruating woman, and the shaman’s exposure of his buttocks in defeat); the hazards of non-shamans handling shamanic equipment; the idea of confusion and mental control (the warriors’ strange compulsion to wear the fatal object in the box); the power of the spirits, inducing death and madness.

The war shamans of the Tsimshian and Tlingit made extensive use of polished slate mirrors, which they employed as a meditation device in order to make their predictions about the course of a coming battle (Kirby et al. 1995). The idea of the reflected and distorted image seems to have been the key to this, as we see in the similar use made of pieces of natural quartz – shamans would stare into the fractured and opaque crystals ‘to see things in another perspective’ (ibid). They could also be used as magical projectiles, being sent out to kill or injure and then return to their owners (e.g. Cove & MacDonald 1987: 113f, ‘Shaman’s narrative’).

The same war shamans also employed wooden images of their anthropomorphic helping spirits, from whom they could ask for assistance in battle. Among the Haida, a similar function (amongst others) is performed by flat humanoid images made of copper, which have remarkably close parallels in both form and function in the bronze charm-figures of the Ural region (cf. Fedorova 2001; Belocherkovskaja & Tuchmina n.d.). In relation to figures like these, which are common in the circumpolar region in various forms, we can yet again question the interpretation of three-dimensional human forms in Viking material culture: figures like the ithyphallic male from Rällinge, or the various representations of ‘Óðinn’, may represent gods, but there is no reason at all why they should not depict spirits instead.

In his studies of the Chukchi, Bogoraz noted how a large number of the rituals with a malignant or aggressive purpose required some sexual element in their performance (1904–9: 448f), providing the same link between these two themes that we have seen with seiðr, and which we shall expand upon in chapter 6.

Bogoraz describes how a shaman would strip naked and walk outdoors at night, revealing his genitals to the moon and praying that in return the moon would grant him the power to send a hostile spell against his enemies. The receipt of this power was accompanied by motions which, again, remind us of the Sámi ‘eating of souls’. As Bogoraz puts it (1904–9: 449):

He also makes peculiar movements with his mouth, as if catching something, and drawing it inward. This symbolises his desire to catch and eat up the victim.

In the same reference he gives further examples of naked shamans ‘using’ their genitals to project disease onto another person, and to ensnare reindeer. Chukchi folk-tales include a great many stories in which kurg-ene’nilit, ‘mocking’ shamans, use their powers to sexually humiliate men and to rape women, always with the same emphasis on the nudity of the shaman (ibid: 573). A strong theme of sexual violence was found in secular Chukchi society generally, linked to the low status of women, and this applied also to the spirit world as reflected in stories of supernatural beings committing rape (ibid: 588–90).

A similar practice is seen among the East Greenlandic peoples, in a context reminiscent of the Chukchi spirit attacks described above. Here, Inuit shamans would use their own sexual energy to empower evil spirits in the form of tupilaks, the grotesque supernatural creatures often depicted in carvings. Immediately prior to being unleashed to attack an enemy, the tupilak would fellate the shaman and in the resulting ejaculation absorb a portion of his power (Martin Appelt, pers. comm.).

An extension of these patterns on a larger scale were the ‘spell wars’ of the Chukchi, in which feuding families would duel with the aid of sorcery (Bogoraz records several examples, 1904–9: 482f). Occasionally these took the form of sexual magic, as in one case where a shaman constructed a dog of snow, transformed it into a handsome man, and sent it to the enemy camp. The man there made love to a beautiful woman, but in the act transformed back into a dog and ripped her to pieces, bringing her pelvis back to the shaman as a trophy. A similar idea of a dog-man committing acts of sexual destruction – though in the form of a spirit, not a material spell – is found among the Inuit of Baffin Island (Boas 1901: 166).

Such overtones to physical combat are seen in other areas with shamanic traditions. For example, in the Northwest Coast warfare mentioned above, the earliest-known war clubs sometimes have clearly phallic motifs – occasionally the entire club is effectively designed as an erect penis in stone (such as those from the Hagwilget cache on the Skeena river, and others from Hazelton and the surrounding region; Duff 1975: 114–27, 183ff). They include double-ended bi-phallic examples, others decorated with red pigment, and with the head of the penis (i.e. the killing surface of the club) transforming into a snarling animal. Some of the objects resemble clubs, and are clearly related to them, but include other elements such as a curving handle that would enable them to be put to different uses.

It is surely significant that the stone sculpture of the Northwest Coast deals overwhelmingly with the themes of sex and death, often intertwined in a perplexing ambiguity of meaning (see the sensitive essay on these objects in Duff 1975: 12–22; an interesting, if rather strained, queer re-reading of them has also been published in Marshall 2000). The clubs have attributes in common with several other ‘sexual’ objects from the Northwest Coast, such as a sculpture from Sechelt of a masturbating human with both male and female sexual organs, whose phallus is itself anthropomorphic. Duff (1975: 57f) has suggested that all these objects may have been owned by shamans, perhaps for the enacting of instructive ritual dramas, and draws support from a number of myths from the Northwest Coast and further inland. The notion of the shaman as a sexual mediator is central here (see Calkowski 1974), but in this instance linked to the additional domain of physical combat. The clubs clearly contain several layers of symbolic meaning. Spread over a date range that covers the last 2000 years, despite the difficulties of interpretation these weapons suggest that sexual elements clearly played some part in fighting between rival tribes even at this early period.

Having now reviewed the components of the shamanic world-view, in a Norse comparative context, we can now examine the archaeological interpretation of shamanism. Against a general background of work in this field we can focus on Scandinavia, looking briefly at the earlier prehistoric periods. From this we can move on through the Iron Age, to conclude with a consideration of shamanic interpretation in the material culture of the Vikings.