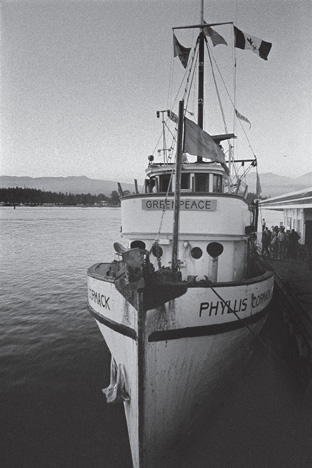

The Phyllis Cormack/Greenpeace departs Vancouver on September 15, 1971.

Greenpeace was a product of the Vietnam War, as much as anything. The precursor to Greenpeace, the Don’t Make a Wave Committee, was founded in 1970, at a time when no issue could stir up a crowd in Vancouver like ‘Nam. The city was sheltering the largest American expatriate crowd in the world, resolutely anti-war to the last love child among them. This was a generation ago, back when TV showed the boys coming home from Southeast Asia in body bags, the after-image of Woodstock was still burned into the public’s retina, the last of the Black Panthers were being gunned down, the Eagle had just landed on the moon, some 56,000 nuclear warheads were ready to be fired, a senility case ruled the Kremlin, and Richard Nixon was on speed in the White House. If you weren’t paranoid, you were crazy.

In fact, the protest against the War was the counterculture’s big-crowd ticket to media glory, having surpassed even Civil Rights as a cause célèbre, although the gunshots that took the lives of Martin Luther King Jr. and Bobby Kennedy were still echoing in our ears. The ecology movement, then known as conservationism, was a weak cousin of The Movement, as the hundreds of anti-establishment groups collectively were called, but the conservationists had also kept themselves apart deliberately. More than a few of them looked upon the American action in Vietnam with favour, and historically, such wonders as national parks had been a Republican cause. The organizers of the Don’t Make a Wave Committee were Jim Bohlen and Irving Stowe, two expat Americans who had fled to Canada so their sons wouldn’t be drafted, and Paul Cote, a Canadian law student. They tried to interest the U.S.-dominated Sierra Club in a protest against American nuclear testing in the Aleutian Islands, but the head office in San Francisco said no.

Thus, by default, the new group started off Canadian, incorporated under the British Columbia Societies Act – a move that turned out to be brilliant. If the committee hadn’t started off in this particular country, it would never have evolved into Greenpeace, a powerful organization of international stature. If the Americans had owned it, they’d never have let it go. Ditto for the Brits, French, and Germans, who now dominate Greenpeace. Only Canucks were liberated enough from nationalism to give it away – but that story unfolded long after the first voyage to Amchitka, which none of us imagined would have a sequel, let alone lead to the formation of an eco-navy, complete with a bureaucracy and a political arm, capable (sometimes) of stopping whole megaprojects, fighting such post-space-age nightmares as ozone depletion, genetically modified food, and climate change.

Ninety percent of history is being there, and Vancouver was the only place in the world where a political entity such as Greenpeace could have been born. We had a critical mass of Americans who were really angry with their government. We had the right legal stuff, with sovereignty and anti-piracy rules on our side. We had the biggest concentration of tree-huggers, radicalized students, garbage-dump stoppers, shit-disturbing unionists, freeway fighters, pot smokers and growers, aging Trotskyites, condo killers, farmland savers, fish preservationists, animal rights activists, back-to-the-landers, vegetarians, nudists, Buddhists, and anti-spraying, anti-pollution marchers and picketers in the country, per capita, in the world. If they could be mobilized en masse alongside The Movement’s long-haired peacenik hordes – ah, well, we would be talking about a revolution, wouldn’t we? John Lennon’s Imagine played mightily in the background, but Bob Dylan warned: don’t follow leaders and watch the parking meters. What was sorely needed was a coherent vision, a philosophy that could embrace them all. From the moment the word “Greenpeace” was first uttered in public, we had it – or we thought we did. Ban the bomb and save the redwoods! Nukes harm trees! At least it was a good start.

Vancouver was the nearest major city to the test zone at Amchitka Island, Alaska, which made it part of the “front line,” even if it was protected by Vancouver Island from any tidal waves that might be triggered by the blast. Earthquakes were also a possibility – the fault line leading to San Andreas passed within miles of Amchitka. These dangers spoke to people’s very sense of territory. Nowhere else did the general population feel as threatened, and so nowhere else was the story as big. There was a high level of awareness among British Columbians that could be drawn upon like an aquifer, and that sustained Greenpeace through its formative years.

On September 15, 1971, the Don’t Make a Wave Committee sent the eighty-foot halibut seiner Phyllis Cormack, temporarily renamed the Greenpeace, to Amchitka. Twelve men were aboard – John Cormack, the captain; Dave Birmingham, the engineer; and ten eco-freaks ranging in age from twenty-four to fifty-two – and along the way we picked up one more crew member. I have heard our trip described as an odyssey, and so it was, in the modern sense. But in the Homeric sense, it wasn’t. The Odyssey came later, on the way back from Troy. The story I chronicle here was Greenpeace’s Iliad.

Cormack was the only skipper on the west coast that the committee could find who was willing to risk his vessel and his life. He brought Birmingham aboard as engineer. The rest of the crew, selected by the committee, were all men – in spite of much talk about New Age-style liberation and equality. This was a sore point, in view of the months of effort that various women had put into raising funds and preparing for the voyage. In fact, the very idea of the trip had been Marie Bohlen’s. The first Greenpeace journey was destined to be every bit as machismo-oriented as the military system it was opposing.

My role on the voyage to Amchitka was that of official chronicler. Not only would I write my regular daily column for The Vancouver Sun and transmit each dispatch from the boat by reading it aloud over the radio, I was also expected to write a book about the experience afterwards – if we survived. Another crew member, a young chemistry student named Bob Keziere, was designated the official photographer. Jack McClelland, Canada’s most famous publisher, was standing by for the manuscript.

How long ago was 1971? I was still taking notes in longhand, not yet having got around to using a tape recorder. Bob was shooting in black and white. Ben Metcalfe, our senior communications ace, had been provided with a National Film Board 35mm movie camera, but he could barely figure out how to turn it on, let alone deploy it in heavy seas or in the thick of the in-fighting. The bit of fuzzy footage that survives shows us staggering about on a water-slicked deck as the Aleutian Islands and their fang-like rocks heave into view. No sound. At a time when television was taking down American foreign policy in Vietnam, we were fighting with ancient weapons – pencils, notebooks, typewriters, black-and-white photos, and a marine side-band radio that worked mainly at night and only when there was no Aurora borealis.

As the ultimate modern theatre of political action, television might as well not have existed. It was like David going into battle with a pea-shooter. I was sensitive to our weakness as a media battleship, having just written a book, The Storming of the Mind (McClelland & Stewart, 1971), calling on ecologists to heed Marshall McLuhan’s advice: take over the control towers of the mass communications system and deliver new images that will liberate people from their primitive tribal mindsets, creating a new global consciousness. I’d even invented a term: “mind-bombing.” My dispatches from the Greenpeace were to be a test of my oh-so-hip media theories.

In reality, just getting the columns out was a nightmare. Sometimes I had to shout out the words one letter at a time over the radio to the rewrite guy in the newsroom, and at a crucial juncture, when we got busted, there was no radio contact at all and I had to send my stuff back on a floatplane that flew out only once a week. I fell so far behind in my reportage that the story of the advance of the Greenpeace was still running in the papers when we were retreating.

The ultimate literary ignominy lay ahead. When I sat down to write about what had happened, I was in terrible shape. I was chain-smoking and guzzling beer. A back injury I’d suffered in a parachute jump years before was driving me crazy, as it always did when I was stressed, so I was gulping down painkillers and I had to sit with half a dozen pillows strapped around and under me so that my lower spine wouldn’t explode as I worked. I couldn’t write at home – kids, marital tensions – and forget the office. I’d have to relate to my journalism colleagues at a time when I doubted my own sanity and was completely befuddled by the experience of forty-three days on a boat with eleven other crazies.

In desperation, I retreated to the Phyllis Cormack, which was tied up for the winter at the harbour in Steveston, south of Vancouver. Nobody else was aboard, so I could pound my head against the wooden fridge door in the galley and torture myself into telling the story, even though I didn’t know yet what had happened to me, or us. History and personal stuff were still mixed up together, and I wasn’t documenting so much as groping for the truth. The trip had become a recurring hallucination. Now I had to shake it out of my head word by word, without breaking the train of barely conscious thought, or risk never being able to write it. You either capture it or you don’t, and you know. I knew, for instance, that everything I was writing through dozens of false starts was shit, even when I had got a dozen pages into it, until the sound of the gulls out on the river flashed me back to the Gulf of Alaska and triggered the flow. Once it was moving, I didn’t dare stop. A voice I’d never heard before emerged and truly spoke for me.

Perversely – almost immediately – I developed a duodenal ulcer. My doctor slapped me on a diet of milk and mashed potatoes and said, “Quit writing the book.” But he was wrong. I needed to write the book. It was pure therapy. Days after the last page passed through my portable Underwood, following a three-week writing binge, the ulcer subsided. I’d written out the story in a single-spaced, one-paragraph, 200-and-some-odd-page stream of consciousness. That was the only way it would come. It was the most sustained, agonizing, ecstatic creative act of my life.

Jack McClelland took one look and shook his Toronto publisher’s head. He ordered Keziere and me to reconstitute the project as a photo book with a simple, spare text. We were pros and we dutifully produced it, even though I was smarting to my artistic core, and it made a beautiful, subversive photo book, thanks to Bob’s artistry (Greenpeace, McClelland and Stewart, 1972). But my poor original angst-ridden prose outburst was axe-dead.

Over the years, as I moved about and worked on other writings, the manuscript got torn apart into segments, some of which got mixed in with other scripts, unfinished novels, essays, word-salad sandwiches, declarations, notes, letters – some archivist may have fun reconstructing it, but my raw reportage effectively disappeared for a generation. I kept meaning to put the story back together but never got around to it. I forgot entirely about the lone photocopy of it that I had laid on Keziere when we worked on the photo book and which, for thirty-two years, remained stuffed in a file among his scrapbooks. Then one fine day in another century, his partner Karen Love came across the copy, like some contemporary Dead Sea scroll, and took it to the editors at Arsenal Pulp Press.

Thus we present a long-forgotten tale from the dawn-time of the New Age. . . .