A toast as the Greenpeace leaves Vancouver. Clockwise from left: Thurston, Metcalfe, Darnell, Cummings, Hunter, Bohlen, Moore, Simmons.

Gulls yowking, diving, plunging like burst white fragments of a single wing, our wake heaving out behind us gurgling and bubbling, one moment falling down from the stern as though we just soared over a hill, next moment our stomachs being dragged up into a pulpy collision with our lungs and the cold grey boil of the wake wagging over our heads. The boat is rolling like a drum and the horizon is only yards away, coming up like a belch, then dropping out from under, and yet somehow instead of falling we are being pushed into slow, agonizing liftoff, and gravity hauls our stomachs back down like lard into slippery squids of intestine – and then whack thunk, as though a boulder had been thrown against the hull, whoosh, down we surf in slow-mo into another canyon, and up rears the bow like the head of a dying mastodon, each upward heave a last gasp. Whack. Thunk.

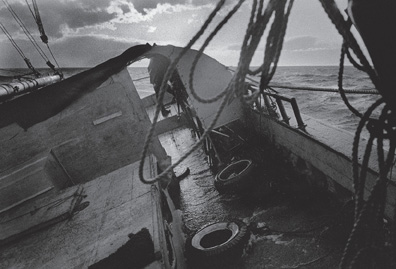

We wallow in water suddenly gone still, disengaged from gravity and tides and current, and then we are swing-heaving and lurch-falling again, fumbling through the troughs and clambering to the tops of roaring ocean hills that collapse beneath us. Hiss of water across the old wooden decks, whose brass hatchways to the hold – built for hauls of halibut – are the exact shape of the ecology symbol, the symbol we have on our sail, along with the peace symbol. And the word GREENPEACE, painted in yellow but now almost impossible to see because the black smoke from the chimney behind the wheelhouse has sooted it out. We poor eco-freaks cringe at the pollution. The engine makes its chugging clunking snik snik snik snik, the smoke ghosting out across the sky, white light flaring along the horizon.

Northbound.

Bob Keziere is down in his bunk, face like a squashed grape, long hair sticky with salt, hardly able to talk and certainly not daring to eat. Not that there is much to eat anyway – the cook, Bill Darnell, is collapsed in the bunk above Keziere, face blank, as if involved in some desperate yoga exercise to remove his consciousness from the long yawns and swoop-plunge-lurch-chop takeoffs of the boat and his guts wildly trying to follow. Pat Moore is wedged in between the galley table and the wall, his shoulders pressed back against the wood, feet jammed against the legs of the table, looking like a spaced-out rock star with his frizz of kinky hair and the poster of Richard Nixon above him, Nixon’s face blurry and the words: LET ME MAKE MYSELF PERFECTLY CLEAR. Our language has come down to grunts and mutterings, everyone tight-jawed, stiff, sore, bruised from being tossed against walls and bunks. The only way to move is to grab something and haul yourself along hand over hand.

To sleep, I curl up in a fetal ball on my bunk, ass wedged against the guard rail, knees jammed into the wall, both hands gripping the cold pipe that runs through the bunk, expecting any minute to be flipped right out over the edge of it. The dreams are fantastic: my kids on a grassy hill on a windswept plain, my little girl running up and down the slope in utter silence, the grass flattened by a giant invisible foot stalking across the world, my little boy sitting quietly in the arms of a monkey who has long silky hair and a glint of supreme intelligence in her eyes. She is brooding over the boy and watching the girl as she runs. It is a dream of evolution – the children are all alone but for the Wise One from out of the past, an ancestral mother. The world as I know it is gone. The world is lost . . . my children! Ah, but it’s a dream, not a vision. It can be explained. Swinging from the rafter over my head is the brown monkey doll my daughter gave me, and the hill and the wind are like the storm and the surging falling sea, and this feeling I have – an urge to sob wildly because my children are out of reach, off in some other world and time, and they will never hear me even if I cry out to them – that can be explained too. I miss them.

But there is more. A painful awe opens up inside me. It has been building for days. The sea is the colour of a basilica – granite, limestone, with foam traces of fossil, a hint of archways built of marble – like an immense wrecked cathedral. Standing out on the deck, I have a stoned-out feeling that leaves me tingling and goosebumped, not just from the icy witch-breaths of wind or the terror that this old halibut boat might roll right over and sink. The peace pennants flapping from the rigging, the red and white Canadian flag and the green and gold Greenpeace flag, and above them all, nailed to the top of the mast, the blue and white United Nations flag, all snapping and crackling in the wind. And this old boat – a kind of funky temple, or at least an art object, floundering through the swells. It is incredible that we eco-freaks should be moving out in an assault on the power that put men on the moon, that could blow up the world, in this boat, the Greenpeace, in her other life the Phyllis Cormack.

She is thirty years old, glossy white with lime trim, with strokes of glistening black along the bumpers of her hull, Rorschach strains of rust running down the enamel like dried blood, and rubber tires dangling from her sides like hippie beads. Her railings, ladders, metal instruments, and huge anchors have been gnawed and sculpted by rust, which is turning green from years of salt water breaking over her decks. The varnish on the wooden walls in the wheelhouse and the john have peeled like films of green skin. She seems a solid piece of wood, this longliner, seiner, fish packer, general anything of a boat, 80 feet long, 102 gross tons, powered by a 17-ton Atlas engine with six cylinders, 230 heavy-duty horsepower and an oil-slicked green mass of machinery, a Disney-animated robot city of pumps and spires and pipes and screaming whirring parts. The noise that blows through the bunks when the hatch to the engine room opens is like an elevated train crashing by. Pipes and fittings and hoses run over the decks, geometric arteries and veins, and the life raft mounted beside the battenclaim is like the one that Captain Ahab rode out in to face down the great white whale. The wheelhouse, which the captain calls the Penthouse, is like the conductor’s booth in an old wooden tram. Six wood-frame windows. A night light over the compass bowl with a thick cloth-wrapped wire running down from it like the tube on a hookah. The barometer hangs there, corroded, utterly useless. You have to hammer the depth sounder with your fist to make it work. The mood on the boat is an atmosphere of communion, an aura of High Mass, and far down the long aisle between the rolling sloshing pews stands the skipper, John C. Cormack, a sorcerer alert to invisible presences and forces. The peace and ecology symbols flap on the big green sail above us like hieroglyphs of some weird religion, a whole new Zen-like view of the universe.

Not one of the Don’t Make a Wave Committee members on board the Greenpeace has set foot in church since he was a kid. Jim Bohlen is a composite materials researcher, space technician, builder of geodesic domes and rocket motors made of filament-wound glass-epoxy resin composites; Pat Moore is a forest biological and interdisciplinary computer simulator man; Terry Simmons is a cultural geographer; Bob Keziere is a chemist and photographer; Bob Cummings writes for the psychedelic mind-blown godless Underground Press; Bill Darnell is a full-time organizer for minority causes; Ben Metcalfe is a theatre critic, journalist, former public relations man; Lyle Thurston is a doctor, about as far into existentialism and phenomenology as you can get without being locked up; Dick Fineberg is an associate professor of political science at the University of Alaska. As for myself, I hate churches with a passion, though I will throw the I Ching and admire it as a psychological toy, and generally I agree with Carl Jung’s notion of synchronicity.

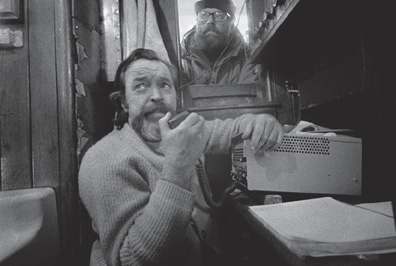

Darnell (left) and Cummings in the wheelhouse.

Yet this protest is somehow connected to the nerve centre where religion dwells, the experience we know as awe. The feeling of awe fills the boat, fills our heads and stays there, throbbing gently. Dave Birmingham, the ship’s engineer, came into the galley one night shortly after we left Vancouver as we were polishing off the last of the wine someone had donated. We were as raunchy and boozy as guys in a troop train, swearing and singing, and Birmingham said, “I must say I’m disappointed. I’d expected the crew of the Greenpeace to be men of religion.” Hoots of laughter and catcalls. But now, more than a week later, out in the Gulf of Alaska, with the ocean thrashing around us, a giant across whose flanks we skitter like insects, holding our breath lest the giant roll over in his slumber and crush us, some crust has cracked, some veneer of sophistication has begun to flake away. The first time Moore opened a can of butter upside down, the captain flew into a rage. “Don’t you thirty-three-pounders know anything? That’s bad luck!” And then Darnell hung a coffee cup on a hook facing inward instead of outward, and the captain flipped out again. “That’s worse luck! Now you’ve done it! We’re in for it now. . . .” Behind his back, we laughed and shook our heads. Did the old goat really believe that shit? Imagine, a superstitious captain! And yet . . . and yet. . . . Maybe, over the years, sunken boats had been found to have cans in them that were opened upside down, or china cups that faced inward. Maybe it was a pattern – inexplicable, probably coincidental, no doubt meaningless – but. . . .

But now we’re out on the Gulf and the swells are coming in 200-foot strides, like a canyon getting up and walking, and, well, when in Rome . . . so we have decided to play it the captain’s way. He has been out on these waters for forty years, he tells us, and “There’s many a brave heart’s gone down to the bottom of the sea.” He loves to spoon out sea talk, calling us thirty-three-pounders or mattress-lovers, talking about waves “high as treetops,” dismissing the heaving sea as “fuck all” because so far nothing has happened, even though we are already at the point where nobody opens a can upside down and in the morning we all run our eyes nervously over the cups on the hooks. But the awe. That’s real – we all feel it.

In less than a week, if everything goes well, we will be within three miles of Amchitka Island, where the Americans will blast off an underground hydrogen bomb 250 times as powerful as the artificial sun that burned over Hiroshima. It might leak radiation. It might trigger an earthquake. It might set a tidal wave in motion. We will be at the gates of hell, it is as simple as that. Maybe we will wave our microphones and cameras and notebooks like crucifixes at the gate, but our tape recorder and marine side-band radio and cameras and other electronic wands, and the hieroglyphs on our sail and the peace pennants flapping from the rigging, are finally not much protection against radiation and shock waves. Moore brought along a Geiger counter, so at least we will know if the decks are being swept by Strontium-90 or Cesium-136 and we can try to make a run for it. The guys who have already had kids – Metcalfe, Bohlen, Birmingham, and I – will go out on deck in slicks and gumboots and try to wash down the walls, while the other guys hole up in the engine room, trying to keep their genes out of reach of the invisible poisons.

The Bomb itself is awesome. When it is triggered, pressure in the firing chamber will rise to more than a hundred million pounds per square inch in about one-millionth of a second, and the temperature will leap to about a hundred million degrees Fahrenheit, instantly vapourizing hundreds of thousands of tons of solid rock, creating a spherical gas-filled chamber in the earth like a giant glazed light bulb. We will be sitting at the edge of the three-mile territorial limit of Amchitka, and the bomb will go off about a mile inland. All ships within fifty miles of the island will have been warned away. The only other human beings in that area will be a group of U.S. Atomic Energy Commission technicians locked up in a concrete bunker mounted on steel springs twenty miles from the test site at the other end of the island, behind a mountain range. The risk? Out of eighty-three underground tests in Nevada, triggered at depths greater than 300 feet, seven tests leaked, so the chances are at least eight out of a hundred. But Nevada is a relatively stable geological area. By contrast, the Aleutian Islands have been described by one geographer as “the scene of some of the freakiest geological happenings on the planet,” where earthquakes strike several times a week and volcanoes are still active. No one knows how much greater that makes the chance of radiation leakage

Two previous tests have been done at Amchitka: a “small” eighty-kiloton blast in 1964 – conducted in secret – and a one-megaton blast in 1969. The first explosion, code-named Longshot, leaked. The second, Milrow, did not. It is a small sample, but the leakage record for tests on the island is one hit, one miss. This third blast will be five times as large as Milrow. It will be called Cannikin, which sounds like something out of the worst early 1950s science fiction pulp magazines – a beast name, like a monster in Lord of the Rings, an atomic fire-breathing dragon. This is the mythical overtone. We are like Bilbo Baggins and the dwarves attempting to get to the lair of Smaug. No – more like the Fellowship of the Ring – the Ring of Power, which for us is the closed-circle ecology symbol – and we are on our way to the dread dark land of Mordor, and Amchitka is Mount Doom, and Cannikin is the very Crack of Doom. Somehow we have to hurl the Ring of Power into the fire and bring down the whole kingdom of the Dark Lord, whose blurred face looks out from the poster in the galley. We are the Fellowship of the Piston Rings. And if there is a sorcerer aboard, a Gandalf the Grey, it is Captain John Cormack, for he is the only one with the magic knowledge that will get us across the ocean and through whatever perilous passes and storms we will run into along the way.

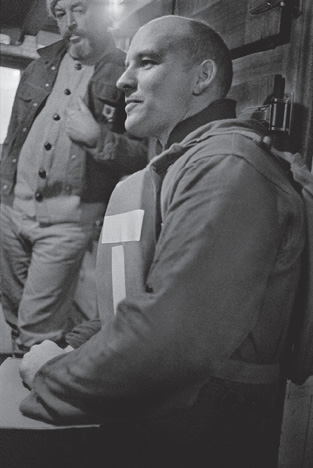

Thurston on deck.

To the rest of us, who have almost no practical experience with the sea, the ocean itself is mythical territory. Moore opens another can upside down and we all pounce and throw the cursed thing overboard. Then fall into giggling fits, we space technicians and hard-nosed journalists, academics, and political radicals, floundering in confusion as we try to grasp new responses appropriate to this weird scene. We should have brought the I Ching. We should have brought a lot of things. But it’s too late now. The awe. . . .

Not just the wonder and vastness of the open sea, but the screwy things that have been happening all the way. Like the synchs Tom Wolfe talks about in The Electric Kool-Aid Acid Test. The synchs happen with mysterious regularity, pieces falling together naturally, forces slipping into play, combinations of events and people so perfect, so beautiful, so weird and unlikely that it rocks our heads, it loosens the old logic, it drives us deeper into the growing sense of awe and magic, the sense that we are part of a vast unfolding pattern of events.

When the journalists among us – Metcalfe, Keziere, and I – attacked the Amchitka plan in print, we had freely used the phrase “nuclear John Wayneism.” One of my pieces, which was read into the Congressional Record in the U.S.A., said that Amchitka might be the Custer’s Last Stand of the weapons-makers. And then, on the very day we pulled out of Vancouver – September 15, 1971 – who pulled in at Victoria, just across the Strait of Georgia, in his converted minesweeper? John Wayne, the reincarnation of mad George Custer himself. Asked about our protest voyage to Amchitka, the arch-cowboy growled, “They’re a bunch of Commies.” It was perfect. Canadians should “mind their own business,” he said With B.C. right in the path of any radiation leaking from Amchitka, right in the path of any tidal wave that might sweep across the Pacific, Wayne’s statement wiped out any remaining public opposition to our protest. Even local ultra-conservatives were suddenly yelling, “Yankee go home!” and cheering us on.

And then, two days out of Vancouver, heading up through Johnstone Strait around the northeast tip of Vancouver Island, we got a radio message from the town of Alert Bay, asking us to stop in. A group of people came down to the dock and gave us a couple of fresh coho salmon. Two Kwak’waka’wakw women, Lucy and Daisy Sewid, came aboard to give us the support of all the aboriginal people on the west coast. They invited us to stop in on the way back and carve our names on a totem pole they were carving, which would be the tallest one in the world. The arch-cowboy was against us and the Indians were on our side.

I had brought along a book called Warriors of the Rainbow, a collection of Native legends and prophecies. In it was a core legend that predicted a time when the Natives would be almost completely wiped out by the white man, and the forests would be chopped down and the water and the skies poisoned. At that time the Natives would rediscover their spirits and teach the white man how to live in the world without wrecking it. They would become Warriors of the Rainbow. Thus baptized by the Kwak’waka’wakw, we headed on up the coast, shaking our heads and laughing at the perfect coincidence. Some time later, Chief Dan George, the only Native North American ever to come within arm’s reach of an Oscar, spoke out publicly against the test. Chief Dan was one of Lyle Thurston’s patients, and when Thurston heard the news, he lay back in his bunk and chuckled and chortled, muttering over and over again, “Unreal! Unreal! Absolutely unreal, man!” John Wayne and the U.S. Atomic Energy Commission vs. Chief Dan George and the Warriors of the Rainbow.

Down in the bunkroom – which we renamed the Opium Den because the ten bunks are stacked in twos in a space the size of a bathroom – someone has tacked up posters of a magnificent ancient blue frigate, ornate as a gingerbread house. Its name is Friendship Frigate, and the sunset into which it sails is pure psychedelic – golden flows of lava and a giant popcorn cloud white as the gulls spilling down around its sails. Down through a cosmos of the blown mind the frigate rides into new eras and new depths of being, a flagship of the Aquarian Age. On its sail, delicate as the pattern on a butterfly wing, is the peace symbol. With that and the ecology symbol, we are one step farther out than Friendship Frigate.

Up the Inside Passage along the west coast we have chugged, flagship of the new consciousness, the Warriors of the Rainbow attacking a nuclear Little Big Horn, with the prayers of the Indians behind us, plowing smoothly through a great technicolor eruption of Beautiful British Columbia postcards, the sweetest Indian summer on the coast in years, the sun sending three-dimensional spots of pure light down on the beer commercial blue waters, mountain slopes rising like perfect Zen states above walls of forest surrounding the boat, rocks drifting by with seams like ancient faces – and down through the narrow passages blew thousands and millions of seeds, each large enough to be an angel insect dancing above the water, glinting like snowflakes against the purple shadows. North through the Strait of Georgia, into Discovery Passage, over the hump of Vancouver Island, through a maze of channels and inlets and sounds and bays and passes and rivers and creeks, up along Johnstone Strait into the wide island-littered mouth of Queen Charlotte Sound, and immediately the motion of the boat changed from slow caboose to long glides of flow and rise, ripples transformed into great booms of rolling water. Then, as suddenly as they had come, the swells were gone, and we were in the shelter of Calvert Island and moving up Fitz Hugh Sound, turning west at Denny Island, through the tight narrow channel of Lamas Passage, winding northward again past Bella Coola, then west out to Milbanke Sound, north into Finlayson Channel, up the long bow of Princess Royal Channel into Wright Sound – a nexus of disintegrating jigsaw puzzle pieces of island, and up the avenue of Grenville Channel, out into Dixon Entrance. Now the faint silver veins of the mountains are engulfed by the swells, and our last glimpse of the continent is a line of rubble, early winter dusk rising like smoke, cold breaths of sea witches fogging the portholes and chilling the decks, sunset a flare of white in the puddles and foam on the poop deck, billows of cloud with traces of dark brass.

The crew of the Greenpeace, photographed by crew-member Keziere. Clockwise from top left: Hunter, Moore, Cummings, Metcalfe, Birmingham, Cormack, Darnell, Simmons, Bohlen, Thurston, Fineberg.

It was never our intention to go to Amchitka and park there through Zero Hour to protest against war. We are eco-freaks, arguing that the world itself was being destroyed. Even without war, we are doomed. Even if the nuclear button is never pressed, within fifty or sixty years we will pass the point of no return and planet Earth will no longer be fit for human life. Cannikin is as much a monster of pollution as of war machinery, and it is the spectre of a dead world that haunts us, that drove us out against the Cold Warriors in this funky old boat.

As it turns out, the northern B.C. coast cannot have been a more perfect place to pass through on our way to Amchitka. It is already the graveyard for a civilization that was devastated by disease, and another that is in the process of decay. Abandoned canneries stand along the shores – patchworks of warehouses made of rusting corrugated sheet metal, broken windows, sheds perched on barnacled pilings, wood collapsed as though burned and swathed in gauze, bull kelp floating among the sagging wharves, jellyfish drifting in the silence. Streams leak down into tiny deltas that gurgle across moon-beds of tideflats, past the wrecks of old fishing boats. Under the impact of technology, the herring population has been dying off. Now the halibut are dwindling and whales are rare. One by one the canneries have been closing down, and as the fish died off, the government stopped issuing fishing licences and cut down on the number of fishermen. The white men devastated the land and then retreated, leaving the Natives to live among the derelict canneries and boats along the beaches. In the Greenpeace we chugged up past stretches of coastline whose deathly silence was like a forewarning of what was to come – the West has already begun its great fall.

Set back in the lush, cool forest, where we couldn’t see them, stood hundreds of petrified creatures, symbols of an earlier devastation, the attack on the magnificent civilizations of the Coast Salish, the Nuuchah-nulth, Kwak’waka’wakw, Bella Coola, Haida, and Tsimshian. No new totem poles or housefronts had joined the aging ones standing like death masks, the skulls splintered and the huge eyes staring out as though hypnotized, tall gods thrown down in a slow green explosion. Some vibration lay tingling on the water, a mood of awe. Another synch – on our way to try to prevent a blow to our own civilization, we pass through the land of one that barely survived its own terrible blow. Destruction happens. Whole civilizations die. There is almost a buzz in the air.

On Sunday, four days out of Vancouver, we were up in the Penthouse and Thurston reverently stacked two stereo cassettes in the wooden tray in front of the wheel – Beethoven’s Fifth and a Moody Blues album, On the Threshold of a Dream. We were all bruised and numb from the batterings of the last few days, groggy from anti-seasickness pills, and the music of the Moody Blues rises from the tape recorder like a flock of birds.

Tell us what you’ve seen

In faraway forgotten lands

Where empires have turned back to sand.

Well, we had seen abandoned canneries and old wrecked fishing boats, and we had picked up a mysterious psychic buzz emanating from the staggered totem poles, and we had seen that fish and whales were dying off and that immense tracts of forest along the coast had been stripped bare. The steering wheel was a torture rack at first, like trying to guide a herd of elephants with one thin rein, and the boat zigzagged slowly for the first few days, swinging one way, then the other, each of us grunting and grappling furiously with the wheel, trying to keep her on course. But the wheel evolved into a mandala, and the chain that clattered and rattled through the first few nights as we swung her wildly this way and that was clinking now like the bracelets of a Tibetan princess.

Sweeps of clouds and light. Triumphs of music moving through the Penthouse as solemnly as the sea. Now not only were we being borne along like a tram, we were being swept by electric swells, rocked in long pendulum-swings of sound. The sunset was the colour of a cataract, but now the light moved up the spectrum only to the lower hues of brass, which matched exactly the mood of the music. Lyrics came through between plunges and wallowings of the boat.

It all unfolds before your eyes.

The music was full of the crashing of cymbals and deeps of a piano. It plunged, it rose, harpsichord passages trailed out like thin wires, organ swells advanced from out in the silence, drumbeats were lured into its orbit, concertos were mustered like storms. It trickled, rained, flowed down through our heads, pianos surfacing like whales, racing toward us with twitching keyboards.

Now you know how nice it feels.

Thurston swayed in the movement of the boat, eyes closed, music crashing down through his mind, toppling him into realms beyond the reach of words. He was humming and conducting the orchestra, which was like calling forth the waves and pulling the clouds across the sky and making the boat surge and pause as it groped through the swells. Everything was in motion, inside Thurston’s head and out. The boundaries had all dissolved. He was back in oceanic consciousness. Thurston, born in Saskatchewan, was perfect material for a sailor – no fear of wide open spaces. No fear, period, as far as I could see, although he did mention that being the ship’s doctor was the best job on a boat until something went wrong, and then it was the worst. The music soared through the Penthouse and echoed down into the Opium Den, luring the other crew members. Moore climbed up through the hatchway. Fineberg wedged himself between the radar and the door. Darnell shed enough seasickness to join us, wearing an engineer’s cap, a string of beads, and flaming yellow suspenders. Keziere groped his way up out of his bunk, still sick and weak, but grooving on the meshings of music and sea motion. Thurston went on conducting the orchestra while I took my turn at the wheel, Cummings puffed on a pipe, and Simmons slouched under the depth sounder, chin bursting with the first prickles of red beard, hands disappearing into the pockets of his blue nylon jacket as though amputated. We all swayed with the Greenpeace and the Moody Blues, jammed together like commuters on a train, saying nothing, just humming along, riding up and up and up to white sky and grey sea and dark varnish-peeling wood and pale wasted faces, down down down toward the bottom of a wide sea valley with a canyon of water marching toward us.

Then the radio room door opened and Bohlen hauled himself into the packed Penthouse, coughing from all the cigarette smoke. “Well,” he said, “the Fabulous Furry Freak Brothers.” He was right – that’s exactly what we looked like, only shaggier and shabbier and more wasted.

He pointed at the tape recorder right beside the compass. “Hey, isn’t that going to throw the magnet off?”

“Nah,” somebody reassured him.

“Are you sure?”

“Sure.”

Actually we weren’t sure, but the scene was so delightful, nobody wanted to mess it up.

In fact, the tape recorder did affect the compass. While we were grooving on the Moody Blues, the Greenpeace wandered ninety miles off course. It was no sweat off our noses – we were well ahead of schedule, at least eleven days to go before Cannikin was expected to go off. But our accidental side trip cost the American taxpayers something like $22,000.

We made no effort to cover our tracks. Metcalfe regularly radioed our position and course to his wife Dorothy. And Dorothy got a request from the Coast Guard commander in Juneau to keep them “posted” – just in case we got in trouble. Wouldn’t want the boys to run into bad weather and not be able to find them. Sure, sure. So on Monday, the day after the Moody Blues sent us off course, a notice went up on the flight schedule board at Kodiak: SEARCH CAN VES GREEN PEACE, and the 17th District of the U.S. Coast Guard, armed with specific data about our speed, position, and course, dispatched a Navy plane, a Hercules HC-130 from Kodiak, Alaska, to run out over the Gulf and get some pictures of us for identification purposes later on. The tab on one hour of flying time for a Hercules was $1,100, and they spent ten hours tracking us because the CAN VES GREEN PEACE wasn’t where it was supposed to be.

Late Monday night the Hercules swung back into Kodiak, not having found a trace of its prey. At the headquarters of the 17th District, the only conclusion to draw was that we had deliberately deceived the Coast Guard, that we were sneaky bastards, and that if we could elude them on the open seas in our thirty-year-old fishing boat that does no more than nine knots at full throttle, what tricks must we have up our sleeves for later, when we got close to Amchitka?

Aircraft surveillance by a U.S. Navy plane dispatched from Kodiak, Alaska.

Yesterday morning the notice went back up on the flight board: SEARCH CAN VES GREEN PEACE. And the Hercules came gliding across the waves at us like a silver steel albatross on the hunt, four long fingers of smoke trailing from its wings, sound mounting from a hiss to a whine to a mutter, a moan, a howl, huuuuuuuuuuuu, down to a wail, a rumble, a faraway wind. Then out and out it headed in the opposite direction. It banked and took another run, like a strafing run, except that the side door was open and they were shooting us with their cameras. Keziere fired back with his Leica, and Metcalfe trundled out the sleek Japanese 15mm movie camera loaned to us by the National Film Board. They took pictures of us for the record and we took pictures of them for the record, and it was a war between two motion picture studios making two completely different movies with completely different bad guys. It was a McLuhan-type war, a war of the icons, a public relations struggle.

In addition to the $22,000 we estimate the Coast Guard spent finding us and photographing us, the Atomic Energy Commission is going to have to spend plenty on public relations to patch up the damage. We have planned for a high level of exposure in the mass media. The only way we can make any impact is to keep ourselves in the spotlight the whole time. That’s why we emphasized media when we selected the crew. Metcalfe would handle public relations. He’d send reports every night to Dorothy, who would immediately dispatch them to radio, TV, newspapers, and wire services. Cummings would file his stuff with Vancouver’s underground paper, The Georgia Straight, which would pass it on to all the underground papers in Canada, the U.S., and Europe via the Liberation News Service. I would pump out a daily column to The Vancouver Sun. Fineberg would get stories out to papers in Alaska and to a small radical wire service called Dispatch International, based in Washington, D.C.

With the delivery of this information to the media as our sling, we will hurl our stone – the Greenpeace – against the American Goliath. Our boat is to be a tiny domino that we will push so that it falls against the larger domino of public opinion in Vancouver. That larger domino will topple the giant domino of public opinion right across Canada, and that giant piece might fall hard enough to knock down the super-pyramid of public opinion in the United States. The last decade of turmoil in the U.S. fused the Civil Rights movement with the anti-war movement, which had its roots in Ban the Bomb, a worldwide campaign that started in Great Britain in the 1950s. Civil Rights demonstrations and peace marches made the walls tremble. Now, virtually overnight, a vast environmental movement has come into being, born out of a sudden awareness that the planet itself is being destroyed. We need to pull this trinity of changes together, fusing the clenched fist and the broken cross and the closed circle of unity. Here, with the notion of Greenpeace, is an alliance that might finally wrest the Cold Warriors out of the control tower. In these times, what larger ambition can be dreamed? It is as monumental a quest as for the Ring of Power.

But power corrupts. Each of us runs the risk of being corroded, like the Bearer of the Ring. Just when Frodo the Hobbit finally reaches the Crack of Doom and is ready to hurl the Ring into the fire to bring down the kingdom of the Dark Lord, the poor guy finds that he can’t let go of the Ring. Its power has corrupted him, taking over his soul.

Metcalfe sensed early in the voyage that we might be in for some heavy shocks and trials, and he gave us two warnings. First, “Fear success.” Second, “Beware of paranoid grandiosity.” Here’s the Encyclopaedia Britannica definition: “Paranoid grandiosity tends to be well organized, relatively stable and persistent. The complexity of delusional conviction varies from rather simple beliefs in one’s alleged talent, attractiveness or inspiration to highly complex, systematized beliefs that one is a great prophet, author, poet, inventor or scientist. The latter extreme belongs to classical paranoia.” Well, the Greenpeace, suffused with our grand ambition to cripple the Megamachine of the nuclear weapons makers, is a floating paranoid grandiosity trap. The ambition gets into our heads, tricking us into thinking we are a hundred or ten thousand times as important as we are, and this can warp our perception of reality. Careful, careful. Tread gingerly along the wire, boys! We have to keep talking each other down from bad paranoid grandiosity trips. Remember, we’re just a dozen middle-class cats out here on an old boat, away from our warm, comfortable Canadian Hobbit holes. All we can hope to do is concentrate public attention on the test at Amchitka, to provide a focal point for opposition – which is growing all the time. All we’ll be doing is what millions of other people have already done – establish a picket line, a floating picket line.

But the trap is slippery with quicksilver. Just before we reached the open sea, the Prime Minister of Canada tried to raise us on the radiophone. He couldn’t get through, but he did issue a statement opposing the test. It was a major political victory – and the beginning of a transformation. In its final edition on Monday, the day the Hercules went out looking for us, The Vancouver Sun ran a full eight-column headline: TRUDEAU CONDEMNS TEST AT AMCHITKA, followed by an article that Dorothy Metcalfe read to us triumphantly over the radio:

Prime Minister Pierre Elliott Trudeau issued a statement Sunday condemning the proposed Amchitka nuclear test – but he failed to get the message to the crew members of the Greenpeace protest vessel. A spokesman for Greenpeace said in Vancouver that Trudeau tried to contact the crew via radio, but the ship was in the Grenville Channel near Prince Rupert and out of radio contact. She is sailing towards Amchitka Island off Alaska in an attempt to halt the nuclear test schedule by the United States government for sometime during the next few weeks. Trudeau’s statement notes his “great concern for an issue which is causing anxiety to Canadians generally and so very much more so to the citizens of B.C.” The statement continues: “The proposed underground nuclear testing at Amchitka has been the subject of numerous consultations between the Canadians and U.S. governments. The Canadian government has informed the United States administration that it cannot agree with the proposed testing and that we believe all such tests should be halted. . . .” Meanwhile, a protest telegram containing 6,000 names was sent to U.S. President Richard Nixon Sunday night by the Canadian Coalition To Stop The Amchitka Bomb.

Well, hurray hurray! It had been a long time since a protest got the backing of a head of state. We cheered – a bit. It was a wishy-washy statement, and when you boiled it down and examined the remains, it was pure cabbage talk. Trudeau merely acknowledged that there was a lot of public feeling against the test. Norman Mailer observed: “In a modern state, the forces of propaganda control leaders as well as citizens, because the forces of propaganda are more complex than the leaders.” But hold on. Nobody thinks for a moment that we can do a single thing to halt the test, unless the Atomic Energy Commission is far more worried about radiation leakage than they admit. If so, they will have to find some way to bust us or kick us out of the area, because if it does leak, and that Geiger counter of Moore’s starts clicking away, we’ll be on the radio getting the news back as fast as we can. And if we get sprayed with radiation, the Atomic Energy Commission will be stuck with a dozen martyrs on its hands, and maybe they don’t like that idea. But halt the test? Careful, now! Fear success, boys! It’s true that right from the day Bohlen announced to the press that a ship would be going to Amchitka, the word “blockade” had been bandied about. Some serious arguments were even put forward to the effect that the Greenpeace may be the straw that breaks the Megamachine’s back. If enough political pressure can be brought to bear, if the issue fires up enough people, if we draw enough attention to the island, then our presence offshore might be enough to tip the scales.

At the same time, there is a weird absence of ego in the protest. The United States can blow up the world if it wants. Can we really pretend to ourselves that we can throw the Cold Warriors to the floor? Maybe we are too modest, too rational. Maybe we need more ego, not less. Enough ego to imagine that we can throw down the empire. The energy that motivates us, that built up the venture and sustained it through amazing transformations, is generated by the urge to stop the bastards. Yet here we are, at the very speartip of the attack, trying to stay cool, to keep our perspective. The call from Trudeau had the effect of making us the unofficial official Canadian Navy, and now the media are watching us like hawks. If the paranoia level twitched upward at the U.S. Coast Guard when their Hercules failed to find us, it was nothing compared to the convulsion of paranoid grandiosity that shuddered through the Greenpeace when we found out that the Prime Minister picked up the phone. Now we had all of Canada behind us.

The pictures that the Yanks took from the Hercules would have shown them clearly that in addition to the life raft near the stern and the two inflatable rafts up behind the Penthouse, there is an aluminum skiff and an outboard motor lying out on the poop deck. In fact, we have seriously discussed the possibility of three or four of us leaping into the skiff at the last minute and making a run for the island. We know that Captain John will not enter the three-mile territorial limit. If he does, his vessel can be confiscated, and each of us is subject to a $10,000 fine and ten years in jail. He will be powerless to stop us from jumping into the skiff in the last hours before the bomb goes off and racing across the water to make a landing on the island. That is, if anybody is willing to do it. The question is open. Each of us will have to make his own decision. At first I guessed that Bohlen and Moore might try it. They strike me as the most radical of the bunch. Will I join them? Well, goddamn, it is going to be an exquisite moment of torture. The mirror will flare to unbearable intensity and there, stark naked and absolutely visible, will be the revelation of each of our essential inner selves, too vivid for any of us ever again to pretend to strength, passion, or conviction that we do not have.

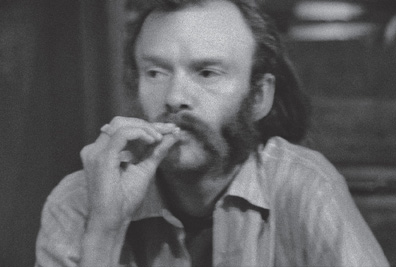

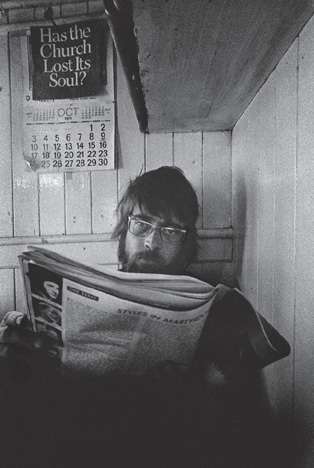

Thurston in his bunk, writing.

It is not the thought of certain death that hangs me up, it is the thought of rotting in jail for ten years. It is hard enough to go through the agony of deciding to go on the damn boat in the first place. Life is sweet in these years on the west coast of Canada, and though the Golden Age is near its end, storms of environmental ruin lie ahead, the oceans will die, the whales and fish will disappear, the land will be poisoned, and the cities will become rat traps of rape and murder and mayhem as they are already becoming in America, and though soon enough radiation will begin to leak from all those places where it is trapped underground or in lead-lined tanks, and though the world will be a gas chamber and a sink hole and millions of people will be killed by famines and plagues – though all of this comes down on our heads like an avalanche, life is still sweet on the west coast. Canada is like the Shire where the peace-loving Hobbits live, sucking on their pipes and eating six times a day, and I don’t want to leave it, leave my wife and kids and good friends and cozy Establishment job. Shit, no.

The other guys on the boat, including Bob Cummings, who is supposed to be our ambassador from the Land of Counterculture, live lives no less sweet. Doc Thurston is, well, a doctor, Moore and Keziere and Simmons work for Establishment universities, Metcalfe for the Establishment Canadian Broadcasting Corporation, Bohlen for the Establishment Government of Canada. Birmingham owns a hunk of land on Vancouver Island and the skipper belongs to the Shipowners Association, the capitalists of the fishing industry, even if he is very much a working-class hero who worked his way up from a deckhand job. Even Darnell, an organizer of minority and environment causes, works for the Company of Young Canadians, a government-funded make-work program that is about as revolutionary as the Boy Scouts. We all live sweet lives, we are part of an aristocracy, so it is doubly hard for us to get our asses moving. We decided that something had to be done, that it wasn’t enough just to write and talk about it, that we needed a real life-or-death engagement. To have gone through all of that and to arrive at a point where we are actually floundering across the Gulf of Alaska, with storms lying up ahead and dangerous passes to manoeuvre in a boat that a number of fishermen told us is too broken-down to get us through, on our way toward the very gates of twentieth-century hell – well, it changed us. It was a tremendous relief finally to be in motion, finally to have joined the army, to be on our way to a battlefield in a war that has to be waged if the tailspin of pollution and war is ever to be halted. A revolution is in the works – nothing less will turn the tide – and once you have joined the Revolution, brothers and sisters, you are smack at the doorway leading into the Temple of Paranoid Grandiosity.

And meanwhile, our tender asses are smarting. Life has become distinctly uncomfortable. Thurston’s porthole leaks and icy water keeps splashing over his feet, while his head is wedged against the wall containing the chimney that runs up from the engine room, which is usually about 120 degrees Fahrenheit, and the thunder of the great Atlas blasts continually from below, and a transom in the floor of the radio room directly above the Opium Den lets through all the LSD shrieks and whistles coming out of the radio at night when Metcalfe or Cummings or I try to get our reports through storms of static to Vancouver (the radio doesn’t work during the day because of all the electromagnetic convulsions lying between us and the shore). What sounds! From the radio comes the noise of a torture chamber, or a lizard being hatched at the dawn of time, screeches and squawks and wild whimpering gurgles. All of this as we try to sleep, while the sound from the engine below – well, a power lawn mower would be a hum in comparison. Explosions of gasoline and air rubbing, clanking, vibrating, spent gases detonating, the fan belt screaming for help, explosions within explosions, cylinders and pistons pounding. Then there’s the clattering and crashing of pots and pans all night long, china dishes smashing on the galley floor, and the weird noises of the sea. What was that? Sounds like . . . like . . . would you believe two giant squids copulating? An enormous underwater bat rubbing its leathery wings against the hull? A human skeleton rattling around in a big tin box? A huge wet kiss being planted on the porthole from outside? Easy to understand where myths and legends about sea monsters come from. You could freak out at night, lying in your bunk, sure that you heard the slap flap flop of a monster from the Black Lagoon walking around on the decks. No chance of sleeping, not with all those noises and the boat still doing its drum-roll acrobatics, great sudden thumps as though – I swear – a boulder has just hit the hull.

And then there’s the problem of having amateurs at the wheel. One night Metcalfe is half asleep on duty in the Penthouse – a sensory deprivation chamber at night, since Cormack insists on no light except for the tiny bulb over the compass, “otherwise you can’t see a damn thing outside.” (But John, I can’t see a damn thing anyway. “Goddamn weak-eyed landlubbers can’t even see at night!”) – and he gets caught unawares by an enormous wave. A sudden lurch, sudden kamikaze leaps of chinaware from the shelves in the galley, exploding like grenades, clatter whang ching of frying pans and kettles and tin cups, and the boat takes a sickening sideways plunge like a buffalo that’s been shot. Metcalfe is thrown down but hangs onto the wheel, whirling the whole boat around, and by the time he can get to his feet and stop the mad spin of the wheel, the boat, which was going due west, is suddenly going due east, and four or five of us have been thrown out of our bunks. Up in the radio room, above the skipper, the wooden guard rail on Fineberg’s bunk breaks when his body is hurled against it, and he sails through the air and lands with a horrible thud. To the rest of us down below, it sounds like the whole Penthouse is splitting and breaking off. Splash and whack of waves snapping against my porthole like wet towels. God, we’re going down! “Oh, fuck around,” yells Thurston. “Shape up, Metcalfe, or you’re fired! Goddamn, what’m I doing here!” Moore: “Isn’t it awful?” Darnell: “Bhleeeee.” Keziere: “Yuks.” He has barely begun to get over his seasickness, and now his stomach is collapsing back into the stew pots. Moving like a man half paralyzed, he gets up and gropes his way to the galley and out the door to puke. No sooner has he pushed open the door than a vast screaming silver and black amoeba of water hits the deck like a thousand sheets of plate glass, soaking him and almost washing him away. “Fuck’s sake,” he mutters, “a guy can’t even have a decent puke around here.”

Somebody starts whistling “We Love You, Greenpeace” – our theme song. We picked it up at Klemtu, the Kitasoo fishing village in Finlayson Channel, 355 miles up the coast from Vancouver. We’d put in there so Cormack could do some welding on a boiler plate, way back in the days when we were chugging up the Inside Passage. My, doesn’t that seem a long time ago, even though we have only been out on the open sea for three or four days – or is it five? The Kitasoo kids had converged on the old rotting wharf where we were moored (symbolic abandoned cannery looming behind them), excited because Keziere and Moore and Thurston and I looked like real hippies, and white society has never produced a figure so loved by Native children as the hippie. “Wow, they look just like us!” It could even be argued that the appearance of the hippie signalled the beginning of the great reversal in white Western society, what with the grandchildren of the cowboys turning out to be more like Indians than spacemen. The only link these kids have with the weird futuristic supercivilization a couple of hundred miles down the coast – as far out of reach as the moon for most of them – is television, and on television they had watched the Greenpeace depart from Vancouver. And here we were, the first television image that had ever come to life in front of them. They swarmed over the decks and hung around for the whole five or six hours we were there.

We walked through the village and rapped with anyone who could talk to us, then slunk back to the boat, guilty and depressed because of the bum deal the Indians were getting, how badly they’d been ripped off by us white people. Now the kids wanted us to come out on deck and perform whatever magic tricks we had done to get ourselves on television. As a matter of fact, we put on a not-bad show. They sang songs and Metcalfe swung out on the upper deck with his tape recorder. The rest of us straggled out on the deck, one by one, in a much better mood, having finished off a couple of bottles of wine and the last of the salmon we’d been given at Alert Bay. The kids went through a bunch of nursery rhymes and the national anthem, to which Keziere responded, “Can’t you do better than that, you kids?” and then they struck up a catchy tune, “We Love You, Conrad,” from the Broadway musical Bye Bye Birdie. After a couple of rounds, the kids started yelling at us to tell them our names. One by one Metcalfe shouted out our names, and one by one the kids sang:

We love you, Uncle Ben,

Oh yes we do,

We love you, Uncle Ben (or Bob or Bill or Dave or Pat or Lyle),

And we’ll be true,

When you’re not near to us, we’re blue,

Oh Uncle Ben, we love you.

The vibes were terrific. Then Darnell shouted, “What do you think of Greenpeace?” And the kids, with us singing along as loud as we could, burst into a beautiful full-throated passionate rendition:

We love you, Greenpeace,

Oh yes we do,

We love you, Greenpeace,

And we’ll be true. . . .

And as the boat chugged away into the darkness, the kids were still singing, “Oh Greenpeace, we love you,” and tearing off their headbands and plastic peace symbols and rings made of beads and throwing them at us and cheering and yelling and whooping, and we were all gathered out on the stern, singing back at them, “We love you, Klemtu!” Damn if Bohlen and I weren’t almost crying by the time it was over.

Since then, whenever things get rough, somebody starts singing or humming “We Love You, Greenpeace” as an anthem, a gentle reminder that it’s a good cause, and let’s not blow our cool. Like now, the boat having swung around 180 degrees while Metcalfe crashed to the floor of the Penthouse, Fineberg crashed to the floor of the radio room, pots and pans and china dishes crash everywhere, and the squid-ink darkness envelops us, waves breaking across the decks, most of us convinced in our half-asleep stupor that the old boat has finally given up the ghost and we are on our way down to Davy Jones’ locker – now we all start singing “We Love You, Greenpeace” between fits of swearing and complaining. Only a couple more weeks, guys, then it’ll all be over and – touchy touchy wood – we’ll all be safe and sound back in our little Hobbit holes and puffing on our pipes and telling fantastic stories about the fire-breathing dragon and the dread land of Mordor and how Captain Cormack’s Lonely Hearts Club Band went out to save the world by. . . .

“Did you say a couple of weeks?” moans Cummings from directly below me. “Aaaaarrrghhh!” Poor Cummings. A year ago – no, longer than that, two years ago – he was described in The Rolling Stone as being “close to the breaking point.” As managing editor of The Georgia Straight, he had been busted repeatedly. The Straight – acknowledged as the most harassed and hassled underground paper in North America – faced so many charges at one point that the editor stood to go to jail for a total of seventeen years. The strain had got to Cummings. He had finally resigned as managing editor and spent the summer recuperating in Mexico. But now he is getting that harassed look again.

Then the blow lands. Moore and Darnell and I are down in the galley when the skipper comes tromping in from the poop deck and says, “Test’s been delayed.” Wham. We let out three simultaneous groans. We are eight days out of Vancouver and within one day’s sailing of the Aleutians, and from there it is only a matter of 400 miles to Amchitka. The delay, according to the newspapers, will set the test back until at least early November. The effect on us is something like what an astronaut might feel if he was descending in his module toward the surface of the moon, and the moon suddenly leapt fifty billion miles away.

We convene a meeting in the galley, which at this moment becomes the boardroom of Greenpeace Inc. There are several questions with no answers attached. Is the report accurate? Is it a trick cooked up by the Atomic Energy Commission to throw us off the track? Or is that pure paranoid grandiosity? The thing is, we don’t have the faintest idea whether the Greenpeace matters or not. It may be that by parking so close to the blast, we are creating a bad political situation for the weapons freaks. Canadian-American relations are at a low point because of a number of otherwise unrelated factors, like trade issues and the Vietnam war and dealings with China. Inevitably, the opposition building up against the test back home is taking on anti-American overtones. Even U.S. congressmen and senators are mumbling about how awful it will be if America’s critical alliances with Canada get too badly strained, Canada having become America’s last great stash of natural resources after they trashed their own. It will not do to have a Canadian boat and crew wiped out at Amchitka, especially a boat with such broad public support that the Prime Minister himself had to endorse the protest. But it isn’t likely that the test has been delayed just to shake us off. Premier Kosygin of Russia is due to arrive in Canada soon for a cross-country tour, and it will be bad diplomacy to blow the bomb while he is on tour. Emperor Hirohito will arrive in Alaska not long after that, and Nixon will be coming up to shake his hand, and it will be even worse diplomacy to blow the bomb virtually under the Emperor’s ass, especially since America’s alliance with Japan is strained as badly as their alliance with Canada. There have been several king-sized demonstrations against the test in Tokyo, the nearest major city to Amchitka. Politics, politics, politics.

Captain Cormack (right) and engineer Birmingham.

The real question is: can we hack it for another whole month? After only eight days, we are smarting. We started out with enough fuel and supplies to last us six weeks, but Darnell says we’ve already gobbled up two weeks’ worth of food. If the bomb does go off in early November – even the first of November – we will find ourselves at the tail end of the Aleutians, only a few hundred miles from the Soviet mainland, with a good two weeks between us and Vancouver. We’ll have nothing to eat or drink and possibly not enough fuel to get there, what with the winter storms blowing down on us from the Bering Sea, and the Gulf of Alaska a convulsion of screeching winds. Bohlen figures we have three choices at this stage. One: we can turn around, go back to Vancouver, and wait until a new date for the test is announced. But they probably won’t announce the date, or at least not until they have to, and Nixon only has to give something like seven days’ warning. We can’t possibly make it back up here in that time. Two: we can head in to Kodiak, park the boat, fly home, wait, then fly back up and carry on. But Cormack says you can’t count on the weather at this time of year. It could take us as long as seventeen days to get from Kodiak to Amchitka, and if we pull into an American port, they may be able to pin us down in red tape. Three: we can keep going, try to find someplace in the Aleutians where we can get supplies, and kill time until we find out when the damn thing is going to go off.

Birmingham (left) and Cormack in the galley.

We quibble and fret for hours. Somebody points out that at least the test has been delayed, which may be a victory of some kind. When was the last time a nuclear test was put off? Maybe we have the bastards on the run. If so, we have no choice but to keep up the pressure. And then up speaks one madman – me – who wants to press on straight to Amchitka, to go into orbit, as it were, around the island, and to go on a hunger strike until the test is cancelled. This idea doesn’t exactly catch fire. “Are you kidding? Who’ll run the boat?” Now our skipper comes down and announces that he thinks the hunger strike idea is great. “If you fellas aren’t gobbling up all the food in sight, like you’re doing now, there’ll be more for me. And I can keep cooking up pancakes and chicken and fried eggs and bacon and porridge and ham and keep myself going for months. Then, as you fellas die off one by one, I’ll throw your carcasses overboard and that’ll cut down on the amount of bickering that’s going on, puh puh puh puh puh puh.” He has the oddest laugh. We can never be certain that he isn’t putting us on. In the end, after a long meeting while the boat flops this way and that, we decide to head for Kodiak.

Some of us climbed into our bunks last night thinking that in the morning we would wake up near the Alaska mainland. But the boat is back on course for the Aleutians. Bohlen and Metcalfe picked up some new information during the night and told Cormack to forget Kodiak. First, there is a military base there, and we might get trapped in red tape. Second, several reports have come in suggesting that the test will not be delayed. Third, the Don’t Make a Wave Committee is running low on funds and isn’t sure it can afford to wait out the delay.

These are all good reasons to stay on course for Amchitka, but they don’t get aired. A new kind of paranoia begins to develop, especially among the younger members of the crew. There are mutterings and grumblings about “unilateral decisions” having been made, but little of this comes out in the open. Officially Bohlen is our “leader.” He is the only representative of the Don’t Make a Wave Committee, the people who raised the money for the protest, got hold of the boat, chose the crew, and generally organized everything. As such, he has the right to make those kinds of decisions, although he keeps insisting that they are to be made by consensus. To adopt that method is to go walking barefoot on all the glowing coals of id and ideology. At the very least, we have set ourselves up for long hours of arguing and debating, finally to be driven back to lobbying and caucus meetings and strategy sessions and – yeah – it is a journey into politics, into all the boring familiar wrangling and power struggling. Bohlen has authority in this action, and he and Metcalfe – the two old vets from the Second World War – are on each other’s wavelength, see themselves as the more mature men on board, and tend to make decisions on their own.

Another month on that boat! This trip is going to be at least a hundred times as heavy as I thought. I look down at Cummings, snoring in his bunk, and think, “Which one of us is going to crack first?” Some conflicts and lines of tension are already showing. Metcalfe can’t stand Fineberg or Simmons, and neither of them can relate to Metcalfe. Cummings and I share an identity problem. For years I have wrestled with the question of whether to quit the Establishment press and go work for the underground press. People tell me, Don’t be silly, you’re much more effective working within the system, you reach more people with your ideas – legalization of dope, support for the Black Panthers and various Red Power groups, environmental revolution, and so on and so forth, up to and including the destruction of mental institutions and schools. The argument has substance. Why write to the converted? Still, it gnaws at me. Cummings, who works for the underground press, would be happier with my job – I think. The mirror image of yourself is the one you hate most, and we have already become the Alter Ego Kids. Cummings also seems to have caught some of the paranoia that infests the underground press, and that can be contagious.

Then there is the question of Fineberg and Simmons, both academics, versus Metcalfe, born during the Depression, when “If you didn’t wake up with a hard-on on Christmas day, you didn’t have anything to play with.” He is the classic School of Hard Knocks grad, who scrambled his way up through the ranks in the bad old days of Canadian journalism, and he is a tough and competitive son of a bitch. One can imagine that way down in the bottomless existential depths of his mind there smoulders a special hatred of authority figures. My guess is that he was a demon at school, that above all he hated teachers, with their dreary logic and their tiresome power that derived solely from their mastery of blackboard psycho-gymnastics. Well, Fineberg and Simmons are teachers, all right. Both have come quickly, thoroughly to hate Metcalfe, and he in turn has got into the habit of shitting all over their logical rational analytical arguments the moment they open their mouths.

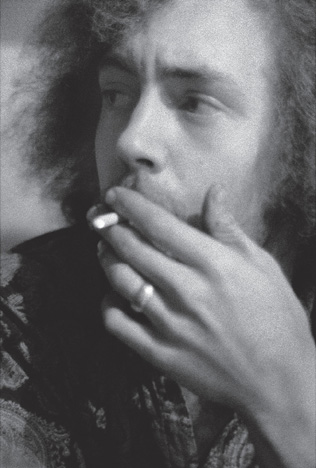

Scene: The Penthouse. Time: Four days out of Vancouver, coming up Grenville Channel, the afternoon that the Prime Minister is trying to reach us. I am at the wheel, quite stoned out by the miraculous natural beauty all around. Cummings wanders in from the upper deck and, like an actor stepping onstage, enters through the right doorway. (By this time we have already given up on “port” and “starboard.” The first night out, Cummings asked the skipper which was which. “That’s the left,” Cormack snorted, “and that’s the right. And that’s straight ahead. Mostly we go straight ahead. Do you think you couple of thirty-three-pounders can remember that?”) Cummings seems nervous. Or is he just acting nervous? I don’t know – to me it seems that he is acting all the time. He is a columnist now, but he had worked as a detective for a while and now he is the president of the Georgia Straight Publishing Company because the editor is expecting an obscenity bust and thinks a good place for the president to be at a time like this is out at sea. He lights a cigarette and leans against the radar, staring straight ahead up the channel. Finally he says, “What’s your opinion of Dick Fineberg?”

Fineberg.

“He’s beautiful,” I reply, trying to avoid whatever’s coming.

“No, seriously,” says Cummings. “Hear me out.” He wags his cigarette in the air to let me know he isn’t kidding. “Nobody really knows him very well. We didn’t check him out, you know. Have you noticed all the notes he’s been taking?”

“You know what? I don’t give a shit.”

But Cummings is determined. “I’m beginning to think he’s an agent for the CIA.”

“That’s ridiculous, man. Absolute crap. You have to be putting me on.” He is talking about the guy who wrote The Dragon Goes North, which exposes U.S. Army germ warfare testing techniques in Alaska, the guy who was invited aboard the Greenpeace in the first place because of another exposé he wrote, about the thousands of tons of poison gas canisters that were dumped into the water not far from Amchitka – canisters that might be smashed by the blast, releasing all sorts of deadly shit into the air.

“No, I’m not. I’ve been watching him.”

“Crap, man,” I say. “Utter crap. Underground press paranoia.”

Cummings gives up. “The trouble with you,” he says, a parting shot, “is that you’ve never been busted. I have.”

I go back to grooving in the slow passage of seamed rock faces and ballets of seeds sweeping down the channel. Moore had pointed to them earlier and said, “Just think, each one of those contains the complete genetic blueprint for a dandelion.”

Thurston wanders in from stage left, camera slung over his shoulder like a tourist. He stands around for a while, fingers tugging at the point of his beard as always. Good old Doc. He’s so cool and together – pure Consciousness III. I am just about to tell him the amusing story of Cummings’ paranoia about Fineberg when he drops his voice, leans toward me, and says, “Listen, Booby, maybe I’m losing my mind, but there’s a rumour going around that Fineberg is working for the CIA.”

“Oh Christ, not you too, Doc!”

“Well, why not? Anything’s possible, man. Put it this way: Do you believe a grand piano could come flying into the wheelhouse? Right now? Think about it.”

“Well, sure. I mean, well, I guess an airplane or something could be passing over . . . the door could pop open . . . and a grand piano could . . . Sure. If you mean anything’s possible, well, yeah, I’d have to be crazy to say it couldn’t happen. Okay.”

“Right on, Booby. There you are. I don’t think Dick’s a CIA agent, but what the hell? Grand pianos, man. That’s where it’s at. This boat’s a grand piano when you think about it. A goddamn theatre critic and a saltchuck sea captain and a geodesic dome builder and, well, you can dig it. Why not a CIA agent thrown in just for the sheer cosmic beauty of it? The States is a crazy place, man. They do things like that, you know.”

A few minutes after Thurston wanders off, enter Simmons from stage right. He’s tied his glasses to his head with string to keep them from falling off in the high seas to come. “Have you been getting wind of the rumours about Fineberg?” he asks.

“Well, they’re a bunch of crap, you know. Somebody’s trying to discredit him. I have my suspicions about who it is, but I’m not saying – yet. The fact is, Fineberg’s been raising some very good questions lately, and certain people don’t want to deal with them.”

“What good questions are those, Terry?”

“Well, for example, there is the very good question about our legal status when we get to Amchitka. Nobody knows. And nobody seems to want to know. Fineberg has been saying that we at least ought to get some lawyers working on it. He knows some good marine lawyers in Alaska who are willing to look into it for us. . . .” Simmons departs.

A while later, here comes Metcalfe, a copy of The Strange Last Voyage of Donald Crowhurst in his hand. “This is a hell of a book to be reading on a trip like this,” he says. “You know, I don’t know what it is, but I can’t quite get it out of my head. There’s something about Fineberg that bothers me. Have you noticed it? It’s more of gut feeling than anything else. But . . . something.”

Just as my turn at the wheel is ending, Bohlen saunters in, looking elfishly happy. “Great day, eh?”

“Sure. Listen, Jim. Have you been picking up on all these rumours about Fineberg?”

“What rumours?”

“About him being a CIA agent and all that shit.”

“Uh-oh. Don’t go spreading rumours like that.” Christ, now I’m caught in it too. “Listen, man,” says Bohlen, “I lived in the States too long not to be able to spot a CIA. Believe me, our boy Dick isn’t the type.”

“Well, you’d better do something to calm everybody down.”

“Me? You do something. I want to look at the scenery. Come on, quit hogging the wheel. Isn’t this something else?”

Climbing down the ladder to the bunkroom, I can hear Metcalfe, Simmons, and Fineberg arguing in the galley. To avoid the whole mess, I duck out the side door. Moore is out on deck, leaning against the forecastle wall, staring at the incredible mountains and forests flowing by. “Jesus,” he says, “have you been picking up on all the bad vibes floating around about Dick Fineberg? Whew. He wouldn’t be a CIA agent, would he? That would be awful.”

Metcalfe at the radio. Bohlen looks on.

Later, Fineberg comes out to the battenclaim and complains to Keziere and me that he’s being shat all over every time he opens his mouth to make a logical point.

Still seasick, Keziere lifts his pale waste of a face and says, “Dick. This may not be the most logic-oriented crew you could ask for. But it just so happens that it’s the only crew in a boat on its way to Amchitka right now, man. Either you can dig it or you can’t.”

“I see. Just keep my place, hmm?”

“No, that’s not what I meant, man.”

End of first paranoia scene.

Now we are nearing the Aleutians, faced with the likelihood that we will have to live one on top of another for at least another month, with the pressure getting heavier every day, Simmons and Fineberg permanently uptight about Metcalfe, Cummings and I glaring at each other like Dorian Grey and his portrait, and Metcalfe. . . . Well, the whole thing started when Fineberg posted a letter to his lawyer from Klemtu without showing it to any of us first. On Sunday Bohlen called a meeting and Metcalfe suggested that Fineberg might be an agent of the CIA or the Atomic Energy Commission. The meeting decided that he should stop working as a journalist aboard, and just serve as crew or cook. In Metcalfe’s view, Fineberg created a bad feeling in the group by going his own way and lobbying Simmons and Keziere. Metcalfe and Bohlen made Fineberg send a telegram to his lawyer in Fairbanks, saying that the Greenpeace dissociated itself from Fineberg’s letter and ordering him not to contact anyone aboard the Greenpeace, including Fineberg. At that meeting, which got dubbed the Langara Episode for Langara Island, which we were passing at the time, Fineberg angrily denied being interested in the voyage as an exercise in journalism. But who among us could say what was really going on, deep in his own head? Could Metcalfe or Cummings or I deny all of our instincts as newsmen?

By that time, some fine levels of suppressed fury were at work. Simmons was outraged by Metcalfe – with justification, for he had been in on the planning of the voyage right from the beginning. He had had to hassle directly with the Sierra Club in the U.S. about it, because the Americans were slightly uptight about allowing the club’s good name to be involved in such a reckless venture. During the two years from the time the scheme was hatched to the night the boat pulled away, Simmons had worked like a fanatic, on everything from high-level executive meetings to shifts on the forklift, loading fuel drums. He had put in hundreds of hours, often when other people were just wandering about dramatically, uttering profound thoughts. Metcalfe, on the other hand, had been involved in little of the manual toil that went into the preparation. So now it was all Simmons could do to stop himself from busting Metcalfe’s teeth all over the deck.

Then there is the larger, more critical problem of the skipper and his feelings toward the whole lot of us – a trip in itself. Cormack is fifty-eight, the oldest guy on board. Next comes Birmingham, who is fifty-six. Then Metcalfe, fifty-two. Bohlen, forty-five. And then a decade drop to Thurston and Keziere, both thirty-four. Fineberg and Cummings, thirty-one. Me, twenty-nine (soon to traumatically turn thirty). Darnell and Simmons, twenty-five. Moore, twenty-four. Cormack went to sea in 1928 as a deckhand on the Union Steamship Catala and has been looking into the moods and rages of the ocean for longer than most of us have been alive. He is short, weighs 240 pounds, and is bald except for a wisp of white hair. His left hand is next to useless – “Only good for eating cookies.” One finger ends just below where the fingernail should start. His right hand is a mess of seams and stitches. One day years ago, when he was out fishing, a nylon rope strong enough to bear twenty tons of tension had snapped, and the chain it was attached to exploded in Cormack’s hands. He was thrown onto the deck, and even as he crashed down, he was thrusting both hands toward the sky. “Call a fuckin’ airplane!” he roared, blood spurting from his smashed hands. Some crewmen threw up just at the sight of the bubbling squirting blood and bits of yellow bone sticking out of purple and black boils of skin. But Cormack was on his feet, bouncing from the deck like a rubber ball, hands flung heavenward, tromping into the galley, yelling at the cook to wrap his hands in towels. He sat there cursing steadily until a seaplane arrived, then clambered out into a skiff, hands still up in the air, and out to the plane. He rode all the way into the nearest port, then out of the plane and into a taxi, arms up like the branches of a tree with bloodstained nests at the top, and down to the hospital. Most men would have fled into unconsciousness or at least collapsed, but John Cormack – well, he has the survival reflexes of an old wild bull. If his head sometimes seems like a steel ball that has been ricocheting between iron walls for a century or two, it is only to be expected after the shit he must have gone through, hammering his way up from deckhand to shipowner in one of the most competitive hard-rock professions on earth. The few old skippers who have survived as long as Cormack are tough, that’s all there is to it. Even at fifty-eight years of age he is strong enough to take on any of us and several combinations of us, and scatter us over the decks like children.

Cormack has a habit of being the last guy to come into the galley at suppertime. Three or four of us usually jam ourselves into the bench between the table and the back wall, and Cormack loves to carve out space for his huge bulk by freely chopping away at the nearest guy with his elbow, driving the lot of us down toward the other end of the table. One morning, in a particularly bad mood, I made the mistake of thinking piss on this, you old bastard, I’m tired of being your punching bag, and when he started chopping at me with his elbow, I dipped into my own bag of tricks (a Purple Belt in Butokan Karate) and let him have a fairly solid side-handed chop in the ribs. There was a pause of about one-twentieth of a second while the skipper’s eyes came level with mine – just enough time for me to realize that he had not made it to where he was by allowing himself to be beaten at anything, and wham – his elbow crunched back into my shoulder damn near hard enough to dislocate it. It would be a fight to the death or nothing. “Right, ah ha ha ha,” I said. “You want me to move over? I’ll move over.”

Hunter at the bow.

Cormack is naturally suspicious of pro-fessors (Fineberg, Keziere, Simmons, Bohlen, Moore, and Darnell, who have degrees of one kind or another). He is also wary of re-porters (Metcalfe, Cummings, and me) – mainly because we were too eager, as we headed up the Inside Passage, to file stories about the engine suddenly conking out one morning. Any reference to his boat breaking down is like a slap on the face. He was so furious about one of Metcalfe’s broadcasts that he threatened to throw us all off at Prince Rupert. But now we have been together long enough for him to sort us out according to our personalities, rather than our social roles, and he has become pretty comfortable with us. Except Thurston and Darnell. Darnell he can’t stand. The rest of us think Darnell is doing a damn fine job of cooking, and he is a calm and stoic presence in the crew, but the skipper keeps muttering, “Now that Darnell fella – if this was a regular trip, I’d have fired him and kicked him off back at Alert Bay. Goddamn mattress lover, that’s what he is. Calls that goop he serves us food. A cook like him wouldn’t last two days on a regular fish run. . . .” As for Thurston, he’s a doctor, and doctors are about as close to a priest class or a shaman or a wizard as you can get in Western society, so Cormack remains convinced that even if the rest of us are loonies, surely the doctor is a respectable gentleman. Yet here is this bearded shaggy-haired freak. Cormack keeps shaking his head. Can’t figure it out, how a weirdo like that Lyle Thurston fella ever got to be a doctor.

Meanwhile, up in his bunk over the skipper, Fineberg is writing another letter to his lawyer in Fairbanks, complaining that we are shooting ourselves in the foot by not allowing the letter of the law to guide our strategy. Nobody is accusing him of being a CIA agent any more, but he is still an outsider. So is Cormack, which may be why the two of them hit it off so well, once Cormack stopped thinking of him as Dr Fineberg of the University of Alaska.

Or maybe it’s simply because they are both candy freaks. Fineberg came aboard in Vancouver with boxes of chocolate and bags of candy, not knowing that the captain had a sweet tooth too – or, more precisely, four sweet teeth, the only teeth left in his mouth. We noticed early in the voyage that whenever anybody left a chocolate bar lying around, it disappeared. “Who’s the chocolate bar thief?” we began to ask. It was one of the deeper mysteries of the voyage. “It’s a CIA plot,” said Fineberg, drily. Much later we learned that there was not just one chocolate bar thief on board, but two. I can just see them up in the radio room in the dark of night, whispering. “Pssssst, how many bars did ya cop today? I got three. Picked one from Hunter’s pocket.” “Good work. I got one from Moore while he was out taking a piss.”

Poor Fineberg. As the only official American on board, he is a Big People (as in Lord of the Rings) and the rest of us, including the expatriate Bohlen, think of ourselves as Hobbits. It is totally unfair, ethnocentric, racist – the whole sorry bundle. Fineberg bears up quite gracefully, all things considered.

Thus divided, hung up, the seeds of mutiny already sown, late on a Friday afternoon, while far away some five thousand Canadians are blockading the U.S.–Canada border right across the continent from Vancouver to Fredericton in a protest against the test at Amchitka, we come within view of the Dread Mountains of Mordor.