It’s October.

Word comes through that a demonstration in front of the U.S. Consulate’s office in Vancouver attracted 10,000 students! School boards and principals had refused to allow time off from school to attend the demonstration, yet from all over Vancouver and surrounding areas, from as far away as the town of Hope, ninety miles east, the kids came. It was a Children’s Crusade – they skipped classes in droves and converged on downtown Vancouver, filling up the street in front of the Consulate’s office and spilling over into nearby streets and sidewalks and parking lots. It was the largest demonstration in Vancouver’s history. On the boat, we hang around the radio room all afternoon, jammed together around Metcalfe, hanging on to every word being reported by Dorothy. All our wives and girlfriends and kids are downtown with the kids. Several of us break down and weep. I find myself out on the bow, crying as I have not cried for years – with joy, as people cried during the world wars when news came of a major victory. Ten thousand kids!

The old feeling is back, but it has metamorphosed into a different kind of awe, having nothing to do with miraculous coincidences or planet love. This is pure, sweet, flawlessly human awe, a feeling of unaloneness, of being borne along on a great current of history, of being in touch with your people and time and society. The effect of the demonstration is to fire us as we have not been fired before. “How far?” somebody yells, and in a chorus, we scream, “All the way!” We even borrowed the lines from a John Wayne movie. What a satisfying synch that was! A couple of days after our arrival in Sand Point, the local movie house, a metal Quonset hut, showed The Green Berets, and naturally we went down to see it. Into the theatre trooped the Greenhawks to confront the image of the Green Berets. It is possibly the worst film I’ve ever seen. Thurston and I gave up after twenty minutes and stalked out and went down to the bar. “So that’s what they’re like,” Thurston mutters, meaning the whole bundle of assholes from John Wayne to the Atomic Energy Commission, with Dick Nixon and the U.S. Army included. They are madmen! But there were a few good lines in the movie. At one point, one of the “heroes” in the movie says, as they rise in a helicopter to go murder some more Vietnamese, “This trip’ll make LSD look like an aspirin.” The Greenhawks screamed with laughter, although no one in the theatre laughed with us. Yep, our own trip is making LSD look like an aspirin. “How far?” yells John Wayne to a passing phalanx of shaven androids, and, click, C-90 psychotronic tape having been slotted into place, they respond: “All the way!”

“You know the worst part of it all,” said Thurston, slumped at our table in the bar, “John Wayne’s probably real. What does that do to your sense of cosmic justice, Booby? Shoots it all to fucking hell, doesn’t it? Grand pianos, man. Grand pianos. The Green Berets. Barf, upchuck, puke, and all that. Oh Christ, blow the bomb! Let’s get it over with. Let the ants take over, man. Or even the sand fleas. I don’t give a shit any more.”

Old Jock wrapped in all those layers of clothes, bobbing helplessly in the icy kill-a-man-in-one-minute waves, being hurled seventy feet in the air, riding like a cork, absolutely unable to move because he’s got so much clothing on, the towels blinding him, whirled through those fierce rollercoaster plunges, wind coming at him a hundred miles an hour – can he hear the shrieking speed-crazed sea witch taking the final leap into the mind catacombs of total freakout? He knows the sand fleas will come, but he can’t move his arms or legs to claw the life jackets free and sink blissfully into numbness. Now, after eternities inside eternities of waiting to be transported into death, the life spark dulled enough that he does not feel the seething sand flea colonies first mining the pores in his skin and then, in nibbling tearing masses of thousands, stripping away his flesh and organs. No longer can he even twitch, let alone unbuckle the life jackets. He is doomed to a very long dying, and that’s what you get for fighting so hard to live, Old Jock! Oh yes, you’re the jaw muscles writhing within the wads of towel to keep opening the mouth for another breath of air, and not knowing whether it’s going to be air or water that finally penetrates the masks that smother and strangle you. You don’t know which way is up.

Oh, the dreams are getting bad at night. I wake up in the small dark space of the Opium Den, sweat gone putrid hanging in the air, and guys in the galley arguing or babbling away, each guy so familiar by now that I already know what he’s going to say on any given subject. It is maddening to have to pretend to listen – or worse, to say anything myself, because my own act, my own set of pre-programmed responses, my own bullshit, are just as transparent and obvious, and communication has become a treadmill – Christ, I can’t stand it. I awake from the dream of being Old Jock, back in my little coffin-sized bunk, the jerk-off curtain closed, pitch black darkness all around except for a silhouette visible through the porthole – spooky-looking wharf pilings covered with barnacles. All too familiar voices echo from the galley, Cummings, Moore, and Bohlen doing their routines, the same old blather, the same old bullshit, the same goddamn con games and psychological manouevrings, each guy locked into the trap of being himself, no other. And so no real growth takes place, no evolution, no breakthroughs into new lands of understanding. We are trapped in moulds like toy soldiers. None of us, not even the freest wildest craziest soul on board – and surely we are an usually free wild crazy bunch to begin with – can break free and become something beyond himself, something better.

Lying in my bunk, struggling against panic as Old Jock must have struggled, I can feel my mind whirling through the sea witch’s freakout scream – and yeah, I am starting to crack up. The notes in my log book go like this: Sept. 22, Weds. So this is what numbness is all about . . . Sept. 27, Mon. So this is what they mean by heaven . . . Sept. 30, Thurs. So this is frustration . . . Oct. 3, Sun. So now I know what they mean by terror . . . Oct. 5, Tues. Here’s real homesickness. And now, desperately pulling the chain on my naked little light bulb, not the dark any longer! I reach for the log book, shaking, gulping a bit as I write: This is either claustrophobia or insanity. Schizophrenia? Panic? Emotional exhaustion? No, I think I’m just going crazy.

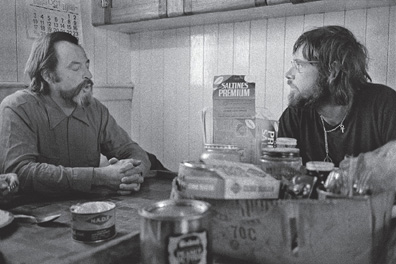

Metcalfe and Thurston.

On the other guy’s faces I see the same wild look that I saw on my own face when I dared to look in the mirror. Lines all over my forehead like a road map and fantastic hollows developing under my cheekbones. The look is subtle, the chin has vanished into a gritty stubble of hair, but a skull-face is emerging, so now I half-close my eyes each time I walk past the mirror. And the other guys are beginning to get that same look. Cummings has a permanent mad light in his eyes. Moore stares out into Old Jock nightmare land. Thurston grows crankier and bitchier and less tolerant of everybody. He shouts at Cormack, at Cummings, at Birmingham. But they are all shouting too. Cormack always shouts – we hardly ever hear him just talk – and he has been like this since the beginning. Maybe we are getting like him. Times when I think I’m just casually rapping away, I suddenly realize from the faces of the other guys that I’ve been shouting again. Oops! Slow down. Wind ‘er down there, baby. Coooool ‘er out.

Some guys are less flappable than others. Metcalfe still speaks in that soft controlled purring voice – the voice of an aristocrat – but now there are breakdowns even in that humming machinery. Now, more and more frequently, a harsh tense uncool tone sneaks through, and Metcalfe’s image in my mind grows a bit fuzzy, then blurred, and then it begins to come apart at the seams and suddenly there is a complete stranger sitting across the table from me, an enemy, a man somehow threatening me. Where has Uncle Ben gone? Where is the guy who kept us in fits of laughter all across the Gulf, who dragged out those ancient Broadway musical tunes?

We have all got into the habit of singing “Would You Like to Swing on a Star?” But we replace the last word in the main lyric with our own weird combinations. “Or would you rather be a horny old man?” “Or would you rather be a chocolate-bar-crazed sea captain?” “Or would you rather be a . . . sand flea-eaten corpse?” Old father image mature war veteran cool hip all together Uncle Ben has gone through some awful transformation. So has everybody else. The social games we played with each other at first have given way. We have begun to slide in and out of our very own self-images, and the images we project on each other have begun to shift. What is going on? Are they really changing, or is my perception getting distorted? Has Moore, the guy I understood to be one of the iron radicals, really changed into a more gentle lovable sensitive character, almost a flower child, or is the pressure getting to me? Maybe I was wildly off the mark when I formed my first impression of him, way way way back (it seems like years ago) when we first got together on the boat. Cormack seemed like such a big tough no-talking bulldozer of a man, and now he reminds me of a beloved old uncle of mine who was always babbling and yakking and rapping away, couldn’t shut him up. Who has changed, Cormack or me? I saw Cummings as strong and rock solid, but now he’s strung out so tight that he’ll crack like an egg if I so much as knock at his head with my knuckle. Or am I projecting my own tension and anxiety on him? What about Birmingham, docile and absurdly subservient, going hard as nails, getting angry more and more often, turning into an argumentative speed-rapping guy? And where has Bohlen gone? In his place a drawn-looking old man, half-slumped over the table, with the occasional flash of the old elf-humour or a twinkle in the eye. On and on it goes.

The trouble is, the voyage did not just get underway – how long ago? God, almost a month! No, it got underway two years ago, just before the 1969 test at Amchitka. Six thousand university students rushed down to the U.S.–Canada border south of Vancouver and sealed it for the first time since the War of 1812. Some 10,000 Canadians across the country did the same in protest against testing at Amchitka. In the days that followed, several newly formed environmental groups, including the Sierra Club and the Don’t Make a Wave Committee, got together to dream up an even more effective demonstration against the next test. Bohlen worked with both groups from the beginning, Moore was in on it, Darnell coined the word “Greenpeace” to name the various alliances under one umbrella, and Bohlen’s wife Marie came up with the idea of sending out a boat to establish a floating picket line. One by one over the next two years, the rest of us joined in, as volunteers. Fineberg was the only one who didn’t get involved until shortly before the boat departed. Captain John Cormack knew what he was in for a year ahead of time, when he agreed to charter his boat for the trip, and Birmingham joined up several months ago, when Cormack phoned him up and asked him. So we pushed and strained for a long time to get the trip underway, and we have lived under the shadow of Cannikin for at least a year on average, and we have put in thousands of man-hours of organizing, planning, political wrangling, and the rest. In a way we were exhausted even before we set foot on the boat. Now, with everything going wrong that can possibly go wrong – the test being delayed further every day, a ruling overturned in a lower court, a new suit launched from one place, another from somewhere else, more and more politicians speaking out against the test, demonstrations building in pitch, pressure mounting steadily – the worst part of it is that we can’t just get our confrontation over with. We can only hang on and try to hold our position until the issue is resolved one way or another. Then we will either have our face-to-face encounter with Cannikin or we will not, and for the first time in history, an H-bomb test will have been cancelled. It is all so goddamn important, and yet here I am in my bunk, gasping for air, being driven to the edge by such petty matters as Cummings’ habit of using my typewriter, Fineberg’s butt-picky way of quibbling endlessly about minor strategic points, the sound of Thurston’s laughter which stings me like an electric shock, and Cormack’s inability to talk rather than yelling all the time. And everybody’s getting just like him, shouting about nothing.

No, no, stop. Got to get a perspective on this thing. All this trivial bickering – surely to God we’re above that. Ten thousand kids. Presidential candidates and B.C. Natives and Coast Guard guys expressing support. Border blockades, the Prime Minister, tens of thousands of people signing petitions and marching in the streets. Zoe has started an all-night vigil in front of the U.S. Consulate’s office in Vancouver, out there with our kids and the other guys’ wives and lovers, and they will stay there until the Greenpeace comes home – if it comes home. It must be real! It must matter! But each day we proceed farther down into the valley. Each day our arguments are powered less by reason and more by emotion. We try to cling to the reason – the reason we are out here, the reason to keep struggling, the reason for being. “Reason is a season,” says Thurston. “Then there’s a new season, and reason means something else. One man’s magic is another man’s routine. One man’s truth is another man’s lie. Philosophy is so fucking easy, man. It’s cheap as shit.” Pages torn from notebooks and scribbled with aphorisms are starting to appear on the walls of the galley.

MASTURBATION IS THE PREROGATIVE OF THE ESTABLISHMENT PRES

IN VIOLENCE IS THE PRESERVATION OF SOCIAL ORDER

FROM TERROR ONE ESCAPES SCREAMING

BUT FEAR HAS A STRANGE SEDUCTION

REALITY: A FEDERAL OR PROVINCIAL RESPONSIBILITY?

TODAY IS EITHER THE FIRST AND/OR LAST DAY OF THE REST OF YOUR LIFE

NO! PUT IT BACK IN!

DEEP INSIDE EVERY NEWSPAPERMAN THERE IS A WHORE STRUGGLING TO BE LET OUT

A CRAB IS YOUR CAPTAIN

A FLOWER IS YOUR MIND

A SAND FLEA IS YOUR BROTHER

GOD IS ZENO’S PARADOX

ZENO’S PARADOX IS YOUR BROTHER

THIS TRIP’LL MAKE ZENO’S PARADOX LOOK LIKE AN ASPIRIN

Zeno’s Paradox goes like this: Take the distance between two points and cut it in half. Then take the distance between the two new points and cut that in half. Take those two points and cut that distance in half. According to Zeno, if you have instruments precise enough to do it, you can keep on halving the distance and never at any moment will the two points come together. That is exactly the feeling we have – the two points are Vancouver and Amchitka, and we will never get there.

The arguments around the galley table are getting jagged at the edges, like broken beer bottles. Old hassles, such as whether Dick Fineberg was a CIA agent, seem long ago, far away, and downright quaint. Such a trifling issue, and safe in a clearly defined frame – objective: Amchitka. There was a game-like quality to the bickering in those days. Somewhere in the back of my mind I was constantly, frantically taking notes – got to remember that line! Uh oh, look what’s going on over here! And laughing at the whole show, which was a gas. Grand pianos, man – how did you ever get yourself into this scene?

But all that has changed. All of us are being flushed out into the open. The cracks that we make about each other are like razors now. Before, when we were all united in our objective – getting to Amchitka – we pulled our punches. Our meetings on the way up the Inside Passage had the quality of boys gathering in the pub after a day’s work. Out on the Gulf of Alaska, the meetings were less chummy, more formal. They became forums, but there were rules, and the mood was almost pure board room. By Akutan, our meetings were veering in the direction of encounter sessions, with the board-room lid holding, but shaky.

The Sand Point meetings are something else. They have the stamp of psychodrama. The objective has gone out of focus. Initially it was Amchitka or bust, but now we have been busted, so what is the point of the exercise? Do we want simply to sail up to Amchitka as tourists, coincidentally arriving on the day of Cannikin’s awakening? Was Amchitka our goal, or Cannikin? The two used to mean exactly the same thing, but now, although Amchitka is still within reach – we can start out tomorrow and head straight for the place – Cannikin has taken wing from its nest. It is no longer a specific time or place. It has started to leap nimbly about – it seems to want to play tag.

Money was a problem. Thurston is losing about a hundred bucks a day maintaining his practice while he is away, Moore, Keziere, and Bohlen all stand to lose their jobs if they are not back within six weeks, Metcalfe’s freelance work is going all to hell, and Birmingham is feeling the pinch. And a new division has opened within the ranks. Some of us are getting paid for this work and some aren’t. Fineberg turned down his grant to be part of the crew, but that has freed him from deadlines and work schedules. Moore gave up his teaching job at Simon Fraser University, so he has no deadline either. Cummings is on assignment for The Georgia Straight and can stay out here as long as the story lasts. Darnell is still getting his pittance as a volunteer for the Company of Young Canadians, and I am still getting paid for writing my column for The Vancouver Sun. What has all that to do with the good fight, the battle to stop the bomb, the crusade to head off environmental ruin? There were different sets of needs, different demands, different personal situations. In an army, everybody is more or less in the same boat, but on the Greenpeace, we are not in the same boat. Resentment against me, the paid Sun writer, for instance, was kept nicely under control. Nobody was in it for the money, and my column was helping the cause, so it could be forgiven.

At the outset, the fact that the protest was middle class seemed to have its advantages. We have jobs and families, so we cannot be dismissed as crackpots. But now our middle-class status is starting to take its toll. For us it was not “you have nothing to lose but your chains,” but: “you have lots to lose.” Still, other questions are more critical. Has our purpose been to focus public attention on the insanity of nuclear testing, with special reference to the extravagant hazards at Amchitka? Or has our purpose been to put our bodies across the tracks of the oncoming nuclear troop train? Which is it, a picket line protest, or a life-or-death fight to the finish? A trap door has opened neatly beneath us, and we have to define our goals more precisely, adjust to the new situation, reappraise all our goals, re-examine all our assumptions. Split hairs, nit-pick, cross-examine, review, re-evaluate, re-examine, regurgitate. Are we revolutionaries or reformers? If you look at anything too closely it becomes something else. Magnify a smooth surface just five times and it becomes a scabby shoal. Magnify it ten times and it’s a ruin of craters and pots and wounds. Magnify it a hundred times and the surface becomes another universe completely. A thousand times and it’s another dimension.

Desperately we try to keep the smooth surface in focus, but it is useless. We are faced with a different situation. Should we approach it in the same way we approached the original situation? Or do we have to change our line of attack? We have managed to bring the full weight of Canada to bear against the test, and what more can we do? Except for the brief flurry of press about the near-mutiny of the Confidence crew, the American media have ignored us, so there is not much we can do to apply the kind of pressure in the U.S. that we have in Canada – short of being gored by Cannikin. But was our goal to cause political embarrassment? Or was it to raise awareness of the dangers of nuclear testing, which awareness will grow enough to transform the political apparatus itself? On and on and on. We have begun to split apart under the weight of such questions.

Hunter.

Perhaps the divisions are inevitable. As Metcalfe noted back on the Gulf, we are a “disparate group,” with different backgrounds and different minds and vastly different ways of looking and seeing and understanding things. With a great psychic rrrrrrrriiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiip, the Greenpeace is torn in half. The hope of achieving “consensus” is no longer even a hallucination – it has become a fairy tale. I cannot quite pinpoint the moment it happened, and I do not know whether it has been happening all along, but the moment came when we were no longer the Greenhawks. Suddenly we are twelve men looking at reality from twelve different angles with twelve different sets of viewing equipment. Fights are starting to erupt. I go to bed one night after a six-or seven-hour hassling session feeling so disgusted about everything that I pin a note on my curtain saying FUCK OFF. In the morning there is yelling in the galley, and Darnell is shaking me and saying, “This one is getting out of hand – you’d better get up.” Stagger into the galley with the FUCK OFF sign pinned on my T-shirt. Every day there seems to be some new data-point that has just been picked up by phone or radio, and every new nugget of information seems to have the power to transform the situation entirely. We hassle endlessly about its meaning, throw out ideas about its value, substance, importance, reliability, how it will affect this if that were to happen, how if that got changed, what do we do about those and these? The galley table is the battleground. Like generals we gather around it and fight over strategy, and we are odd generals, for we are the soldiers in the troop ship that is moving about on the map (pray for the day all wars are fought that way!). And now the terrible question comes up: why are we arguing like this? What are our motives? Egoism? Idealism? Obsession? Or cool calculated practical politics? Ahab or Ishmael? Who is the prime ego? Or is there a prime ego? We are a little band of guerrillas, Captain Cormack’s Lonely Hearts Club Band waiting for a Che to emerge.

Simmons enraged. Reflected in the mirror is Metcalfe.

From the beginning, Bohlen has insisted that he would not be the leader, yet in the early stages we allowed Bohlen and Metcalfe to make the decisions, if only because they seemed like natural leaders. But under their leadership we blundered into the customs hassle at Akutan, and now we are all awakening to the responsibility of assuming our own leadership.

Bohlen is as complex as mirrors mounted opposite each other, each reflecting a reflection of the reflection of the reflection, like an endless series of doors opening into other doors, down down down with no end. America is his nemesis – he hates it like a man who would be a saint hates his own impulse to be a demon. There are fine ironies in this situation for Bohlen. At one point in his career, he solved the intricate materials problem that allowed the Monsanto Company to build its all-plastic House of the Future at Disneyland in 1957. Now he wants to smash America. He also worked for a time for the Hercules Company in Princeton, New Jersey, fabricating the materials for the rocket engines of the Polaris and Minutemen ICBMS, and he worked on the motors of a system – then secret – to be known as the Sprint. By 1971 the Sprint was famous as part of the Anti-Ballistic Missile System, and the test at Amchitka was as closely related to the ABMS as the Sprint had once been. At the very least, Bohlen is a man capable of changes. His psyche is a bio-electronic I Ching. To have come from the middle of the machinery of the military-industrial complex to this funky old boat in an attack on his former masters is no minor fluctuation. And though he seemed determined to let the decision be thrashed out by the group, he has had the final say, for he is the only member of the Don’t Make a Wave Committee actually on board the boat, and as such he controls the purse strings. If he says “Turn around,” Captain John will turn around, otherwise he might forfeit his charter fee. Yet Bohlen seems to be straining to keep the options open, so that the main task is to convince him. To this end, Simmons, Fineberg, and I come down solidly on one side, Metcalfe comes down on the other, Bohlen stays in the middle, and the others seem uncertain. In one of his last dispatches from Sand Point, Metcalfe said:

[The crew of the Greenpeace] know that soon, very soon, they’ll have to decide whether they should try to wait out bureaucratic delays of the Amchitka test and take the risk of being plowed under the sands of time. . . . If they do decide to go home, they will have failed only on one point. They will have failed to persuade Prime Minister Trudeau to make a personal appeal to President Nixon in Washington. This will be a rather bitter failure for them, because, while they never dreamed that they could stop the Amchitka test themselves, they did believe that Mr Trudeau would eventually come through with his own personal protest. . . . [But] he has not grasped his nettle. If anything, Mr Trudeau has become an accomplice to the bureaucratic delay in Washington. So now the Greenpeace must contemplate its own nettle. Whether they grasp it will depend to some extent on whether their voyage was planned as a practical protest to help raise public opinion in Canada or whether it was a hero-trip for the gratification of a few egos. I think I can report confidently now that it was rarely, if ever, a hero-trip, and is in little danger of lapsing into one on the frontier of frustration.

Which few egos was Metcalfe referring to? Well, there is Simmons’ ego, and Fineberg’s ego, and Hunter’s ego. We are a strange alliance: the two American academics and a Canadian who dropped out in high school to write books, falling by accident into the position of Establishment press columnist. Simmons and Fineberg are brilliant at their trade – virtually every argument they put forward is valid – but neither is built for speed. Both move their idea pieces out one by one, starting with the pawns and building toward the play when they pounce with their Queens of Logic. Everything has to go step by step. Nothing can be rushed. And in the end, it is all they can do not to unleash a long howl of I Told You So. Both of them live in the agonizing world of being right, but nobody can stand to listen to the unfolding of their cases.

By contrast, my mind seldom trudges – it bounds and skips through star-beds of ideas. I am more like Moore, a metaphysician of high ecology. When I’m up, I’m very very up, and when I’m down, I’m demolished. “You know,” Metcalfe growled at me one afternoon, “the trouble with you is, I can never tell what space your head’s in. It keeps moving all over the place.” Ego. No doubt about it: Hunter has ego. Maybe I’m not so different from John Cormack – I can say the word “defeat,” but can I tolerate it? To the others it must seem that I have abandoned my observer role entirely and have become the spokesman for the three-man rebel faction that wants to plunge on to Amchitka come hell or high water. What do they see as my motive? For years I have been strangling in my own torrents of written rhetoric, and I am sick to death of writing propaganda against industrial growth, arms races, racism, and environmental ruin. Now, finally, a rare and welcome opportunity has arisen to confront the Megamachine head-on. Am I an iron radical, or am I more like Don Quixote? Out on the Gulf one afternoon, with the wind screeching and the boat flip-flopping around wildly, somebody noticed that the Canadian flag was being torn to ribbons, but it was stuck – no one could pull it down. When no one was looking, I sneaked out and climbed to the top of the rigging. One moment I was looking down at the decks, and the next moment I swung far out over the streaming waves. The ladder on the rigging was broken in several places, the rope itself old and frayed, and at the top, I had to stretch my arm to the limit to untangle the flag and rip it free. When I finally made it down, Bohlen looked at me, shook his head, and said: “Now we know what kind of a guy you are. You’re a crazy bastard who’ll do anything.” Yeah. I once wrecked my spine taking a parachute jump without any training, and I have risked my life a hundred times for no good reason. I am either a wild man or driven, and I have been operating on shithouse karma for as long as the Phyllis Cormack has. But I am still alive and, apart from a permanently fucked-up back, still in one piece.

Darnell.

By the time Bohlen calls a meeting for October 12, which turns out to be the Last Meeting, positions have hardened, consensus is hopeless, the crew have polarized, the magic seems dead. There are no miracles in the air, no synchs. The Merry Men in their green uniforms have been reduced to the dreary old gambits of lobbying and hassling, just like a political convention – the party racked by internal divisions, everyone struggling to keep up the appearance of a united front. The last few meetings have deteriorated into shouting matches and new forms of parliamentary style have evolved. Some workers down at the cannery gave us a paper hat with WAKEFIELD’S ALASKA KING CRAB printed on it, and to keep some order in the debate, we agreed that whoever was wearing the KING CRAB hat, and whoever had got hold of the microphone connected to Metcalfe’s ever-present tape recorder, had the floor. Back and forth KING CRAB has been passed. Eloquent speeches have been made beneath it. If you could remove yourself from last night’s meeting for a moment and look in from outside, you’d find a delightfully surreal scene – grown men lunging for the microphone and the hat, each new speaker slamming KING CRAB on his head as he opened his mouth. By the Last Meeting, the KING CRAB hat is torn to tatters and we are using a Wakefield’s hair net as the speaker’s cap. On the table in the middle of everything sits Williwaw, a cat that some local freaks donated and that has no tail, the tiny paper-and-toothpick geodesic dome perched like a sailor’s cap on his head. Who are these hairy bleary characters passing a hair net back and forth and shouting at each other? Battered typewriters lie on the floor under the table, clipboards and notes are spread out among the coffee cans and ketchup and sugar cubes and jam and honey cans – all opened the right side up.

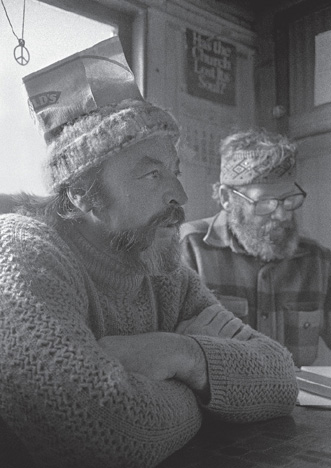

Metcalfe’s turn to speak, as wearer of the WAKEFIELD’S KING CRAB hat. Bohlen listens.

The dozen wetsuits have come and gone. The people back home finally found a diving supply house in Vancouver that would lend us the wetsuits for free, and made complicated arrangements to ship them to Sand Point. When they arrived, it turned out there was a customs hangup – we would have to pay $400 duty on them. We didn’t have the money, so the whole pack of a dozen wetsuits got shipped back.

And now we are into the final hassle, which revolves around the question of the “executive decision” – that is, Who’s the real boss around here? It is Bohlen. Metcalfe says that the executive committee is ultimately responsible to make the decision, “in case the consensus is not a viable and practical consensus. . . . For instance, if the boat was entirely filled with . . . ah . . . ah . . . ah . . . psychedelic kamikaze nuts, you know, who would sail on regardless of the money, regardless of the ability of the ship to do it, regardless of the practical factors.” Simmons agrees that we are not going to get a consensus. He asks a theoretical question: if the executive decides to take the boat back to Vancouver, “What is the potential for a mutiny – quote, unquote – and charging on anyway?” Metcalfe says that the executive will preserve “the Greenpeace idea, ship, concept, funds, charter, etc., etc., . . . as a major tool to awaken the interest and opinion of Canada, and possibly of the United States and the rest of the world, against the Amchitka bomb.” Simmons says that the Amchitka voyage is more of a protest voyage than a propaganda voyage, and that it has failed – the proof being the fact that we are talking about whether or not to go home. “If we were really protestors,” he says, “we would have no question in our minds which direction to go, strictly on a moral and honest point of view.”

Hunter.

I say that if an order was given to go to point X, and suddenly in mid-course the captain said no, and the crew decided to go on to point X, I wouldn’t call it a mutiny. I would say that the mutiny had happened on the bridge.

“The Greenpeace going to meet the Cannikin of October 2 is different from the Greenpeace going to meet the Cannikin of November 2,” says Bohlen. “And other differences have been introduced into our situation. For instance, an astounding success in relation to publicity. . . . And the added factor of weather, and added knowledge of this particular ship from a maintenance and operating and mechanical point of view. We’re talking about two different trips.”

Moore says that a protest in a vacuum is stupid and meaningless, that the purpose of the voyage is to raise awareness. Fineberg points out that we are bound to “peak out” in the day-to-day headlines, and then what? “When you talk about propaganda, you’re talking about a complex thing, and it’s not each headline in the morning newspaper, it’s the people you reach by the example of what you’re doing – that they may be reached by our dedication to the mission and they may not be reached by the headline. When it comes down to whether a person will bomb a dam or lobby for a park or a forest. . . . This is a long-term and a subtle thing, not the same as a front-page headline for a week or two.”

Keziere brings the discussion back to specifics. He says that if we find out the test is absolutely not going to happen in October, we should go back to Vancouver.

Birmingham.

“Beyond that,” he says, “I think that we have definitely fulfilled our obligation and we would be superfluous in staying out here.”

I weigh in as spokesman for the psychedelic kamikaze lunatic fringe, saying that to turn this boat around and go home is certainly to piss away our potential for further success, to stop and say: we’ve done this much, it’s enough, no further, let’s go back. None of us could predict the support that has developed as we continued, things like the 10,000 children, so how can we say that we’ve actualized our potential?

Bohlen says that when we left, a lot of people thought we were loonies, and we proved we weren’t loonies, and now we stand a chance of becoming loonies if we go from Sand Point to Amchitka and back to Sand Point in late October and early November in this particular boat. Moore says we would be foolhardy to venture out in this particular weather. Keziere thinks it would be a mistake to turn around because of the possibility of bad weather.

“What happened to the idea of going back to Kodiak?” Birmingham asks. “Some people need to get off this boat at the end of October, regardless.” He proposes that we go to Kodiak and thin out the crew to five or six men, then proceed. Then he says flatly: “I think there’s several members of this crew’ve definitely made up their minds they’re not going to Amchitka come hell, high water, or anything else. Furthermore, the boat is much safer with six men than it is with twelve.”

When Birmingham drops his gosh-darn-blankety-blank-old-geezer act and gets around to saying his piece, he is almost always right on. Some guys have made up their minds not to go to Amchitka, so do we split the crew and let those who want to keep on going go, and the rest head home? That is the real question.

This morning, the morning after, as we stand on the dock in the rain and prepare to head home, I say to myself: you lost because Bohlen didn’t trust you. Intellectually you’re as powerful as him, but you’re too much of a freak. He feels he has responsibility for everybody’s lives and he will only pass on control to someone whose judgement and maturity he trusts completely. You were doing a lot of crazy things, I point out to myself. Like going around ordaining everybody as a minister in the Greenpeace Church just because you had accidentally become a minister of the Universal Life Church down in some psychedelic place in San Francisco where madmen like Leary hang out. Like the rest of us, Bohlen could see that it was fun, but you did it with the crew of the Confidence and with everybody up on Akutan Mountain, man. And then there was that night when those liberal teachers up at the Sand Point School invited the whole crew over for wine, and you and Thurston came staggering in late from the bar, and you took one look at the bookshelf, saw some innocuous children’s books of prayers and stuff, and you said, “Who’s the Jesus freak around here?” Then you started arguing with them that what the world needed was a religion that took the logical step beyond Christianity into a kind of Eco-Catholicism. Remember when you got back to the boat, and Metcalfe said he’d been waiting for you to show them your stigmata? You jabbering away about Teilhard de Chardin and Marshall McLuhan – it was hard to tell whether you were kidding or serious, man. A flower is your brother. A crab is your brother. A whale is your brother. I am the Earth, we are the Earth, always with a capital E, the way other people say “God.” Then you disappear into the fog after that trip up Akutan Mountain and we have to go look for you and there you are, clutching your notebook, writing “PARANOID GRANDIOSITY IS THE HUMAN SOUL,” and – what was that other beauty? – “I’VE BEEN SANE AND I’VE BEEN INSANE AND BELIEVE ME, INSANE IS BETTER.” And you wonder why Bohlen has doubts about your fucking head? When you wanted to be, you were completely sane in the way that Bohlen recognizes sanity. But the rest of the time you must have seemed pretty weird indeed. Like your legalize suicide idea. “It’s not enough to lower the birth rate, you’ve got to raise the death rate. Why not take over from nature? Introduce death control as well as birth control.” By taking the stigma out of dying, you said. Encourage people to choose their own time and place of dying. Make it a celebration like birth is a celebration, all the friends gathering around and maybe stoned, whatever they want, go up to the top of a beautiful mountain – “Death is just another trip.” Then there was the Greenpeace Church business. The only force that ever threw over empires without arms was religion, you said, and now it would be a scientifically valid religion, based squarely on principles derived from the science of ecology. Make terracide a crime, you said. Some of this made sense and Bohlen even joined in, but you’ve got to admit that the Hash Cookie Pact was too much. Really, man – that when we die, we get cremated and instead of throwing the ashes to the winds, you bake them into a batch of hash cookies, and your friends have a hash cookie wake and get stoned on the essence of you. Bohlen didn’t trust Fineberg and he didn’t trust Simmons, so that left you and Metcalfe. If Metcalfe had wanted to go on, Bohlen would have trusted him to take on the leadership. But Metcalfe was pushing harder than any of us to bring the thing to a head, and he was the guy presenting all the arguments for going back. Metcalfe approached the situation at a practical political level. He’s been involved in public relations and election campaigns, and those things are real to him. He lived mostly among liberals, and they ran for public office and they controlled the show. From his experience of how power actually operates in a democracy, his practical experience, he fought the Amchitka fight the way you would sell toothpaste. He and Bohlen didn’t chicken out. They’ve both been through heavier trips than you, man. Who wanted to go ahead? Thurston thought the boat should go on and everybody who had to leave could split, which included him. Cummings said his vote was to go home, then he bugged out down into the engine room to write a story or something. Cormack didn’t have a vote, but remember that exquisite moment when we had fought it down to the last quivering arm-wrestle, and everybody was wiped out, and Cormack came in and – right, that was your fatal manoeuvre. His opinion was bloody critical, and you knew that he couldn’t admit defeat, that he’d come out balls-on, say, “We can make it. There’s not a damn thing wrong with this boat. This’s the finest sea boat on the whole coast. She’ll take you anywhere. Ain’t no kind of weather this boat can’t handle!” You had it all figured out – Cormack’s confidence would turn the tide. But what you didn’t count on was that after he’d finished his little speech – which came out exactly as you’d guessed – he’d add, in a desperate tone of voice if there ever was one, “But you’d be crazy to try it!” So we wound up with Darnell, Simmons, Fineberg, and you willing to keep on going. That’s all. You lost. I had the feeling that there was a part of you that wanted to lose, a feeling of My God, I can’t get my arm up to swing again. I’m running out of punches. Maybe you even knew that Cormack’s act wouldn’t hold up, that he’d betray himself. In fact, I think you threw the fight. Very clever – you do the balls-on trip all the way, and then when the whole thing balances on a pin, you cleverly allow yourself to be beaten. And wow! At the end you come out the hero in that damn book you knew all along you were going to write, and the other guys are the heavies. But wait. Let me take all that shit back. That night after the vote was over, you said, “Well, all I have to say . . . is. . . .” And then you made this animal noise and literally flew up from the table and went through the galley door so hard you broke the hinge off, and you went out to the stern and cried. If that was an act, it was damn convincing. Then everybody went down to the bar and drank till God knows when. And that weird synch! At midnight, when you looked up and said, “Well, congratulate me. It’s October 13. As of now, I’m thirty years old.” Talk about turning into a pumpkin, man! That was delicious. But by that time you’d lost your sense of humour. Was it ever easy to tell who was the winner and who was the loser, that night in the bar. You were coming apart at the seams.

What is it Metcalfe said? “Never let anyone tell you this is an ego trip – it’s an ego trap.” Every minute of this experience has been so fucking intense – to be so alive is to realize how dead we are normally. Is that a justification for wars and fighting? When people are struggling like that, when they’re out of their snug little boxes – which are traps, they really are – and into some life-or-death action, there’s a payoff. They do come alive. They experience everything much more intensely and at many more levels. If people could wake up from those stale little situations they’re in, and stay awake, there really would be a revolution. You get a taste of it, of being alive, being in a struggle, being a part of a vast and positive fight for survival – that’s what it’s about. Survival on a bigger-than-me scale.

The God is dead business. Yeah, He is dead. And we miss Him, we really do. Because when God is dead, it’s a tricky thing to keep meaning alive. That’s what’s happening in the West. God died and the people were afraid. God took the beautiful dream of immortality away with Him and left us nothing but the void. Timidly people began to feel their way into the void. At about that time, the East and the West began to move into a new stage of harmony. And through the science of ecology, the techniques of systems analysis, the media of mass communications, and existential and phenomenological philosophies, a consciousness has begun rapidly to evolve that can think in terms of wholes instead of parts, that can see the world as a single life system vibrant in the vastness of the cosmos. The Princess Immortality was not taken away by God in his dying. The people were simply blinded and so could not perceive Her in the Earth, in every drop of rain. In the fear of dying was the invention of God, and in the dying of God was the chance to shake off the fear of going back into the Earth to nourish Her and to go on being, in however transmuted a form. God is dead. Long live the Earth!

Hunter on his thirtieth birthday at the bar in Sand Point, Alaska.

Out past the Sand Point wharf, past the grocery store and the little white wooden liquor store, around the peninsula whose tip is the cannery, there is a small hidden bay. Winds come steadily over the far slope and beat at the tall grass, ribbons grey on one side and rinsed-out autumn yellow on the other, rust-hued goldenrod, tumbleweeds caught like giant gangly insects in barbed wire, knocked-down fence posts riddled with termite holes – a scene right out of the rolling hills of old Montana or a lagoon valley on the Saskatchewan prairie in late fall. Old shacks half-hidden in the hushing and shooshing grass, as high as your chest in places, and up on the slope a cluster of rusting Quonset huts. Garbage piled up, old grey nets, a few weathered wooden swings moving in the wind, as though invisible children were pensively swinging on them. Cold – the wind has winter cold in it. Huskies yap from the ends of their ropes, but the sound is carried away on the wind. No sound except for the rare splap tssssshhh of waves being beaten into the bay, a few ancient rowboats clacking together along the gravel beach, and the skrik skrik of tires rubbing the ribs of boats at the little wharf, like an overturned box. In hushes, in breaths that envelop sound, the wind streams down into the cove around the bay. An object very much like a totem pole pushes up clear of the tall waving grass at the top of the rise against the sky – another Russian Orthodox Church. Its windows are all broken and the bottom bar of the double cross has tilted, creating a new religious sign, a whole new denomination. This old heap on the edge of the ghost town ghetto represents perhaps the farthest reaches of the Russian Orthodox Church (in town, all the metaphysical action is down at the Baptist Hall), and now it is a chess piece, a bishop, abandoned in enemy territory. The place is some kind of historic site, though nobody has put a plaque there yet. In the cemetery around the church, small saplings grow between the gravestones. The decks of the empty boats in the bay squeak as the ghosts of old fishermen still walk them, the huskies bark silently, unseen children brood on the swings. . . .

I have wandered down into the cove a dozen times, but almost never have I glimpsed any figure moving among the Quonset huts and the hunkered-down windblown shacks, and no one at all climbing over the old hulks around the dock. Every day the sky is a soiled sheet laid over too many corpses. One small gillnetter is beached on the dirty gravel, a splintering bone of a boat, windows smashed, hull like the wrappings of a mummy – the funkiest old place in the world you could imagine for kids to have their secret clubhouse, a place to duck out of the wind and listen to it hissing through the old rust-scabby engine like a primitive Moog synthesizer left there by an ancient forgotten race. That old boat is a cold spooky sad place to take shelter in, but Thurston and Keziere and I fell in love with it as soon as we saw it, not long after we got to Sand Point. Years ago, somebody painted the word LOU on the hull, in green. Lou is also the name of the girl Keziere is living with, and Thurston and I have gotten to know Lou just well enough that we love her too. That boat is mysteriously cool and together, and it possesses the Secret Wisdom, like the wisdom of mature beautiful women, which has no real counterpart in the world of men. Lovingly, we crowded into the Lou and Keziere warmed himself on the invoked presence of his Lou. Best of all, with the same green paint someone had sloshed a crude peace symbol and the word PEACE on the hull. Here was another Greenpeace, here was the wreck of the Greenpeace, here finally was the past and the future spirit of the Greenpeace – a deep-sinking feeling, for the end is so certain, death can be beautiful, don’t be afraid to go back into the vibrant voids out of which all “things” come into brief focus or brief out-of-focus. In its wise graceful ancestral way, the Lou seemed a finer totem pole-like return to the beginning than even the old chess piece of a Russian Orthodox church up on the hill.

Today, the day after the vote to give up the assault on Amchitka, I walk to town to buy an airline ticket that will get me out of here, moving blindly in a fog of pain and self-loathing, thinking Greenpeace is dead, Greenpeace is dead, I am dead, we are all dead, we are all dying. But Thurston and Keziere head me off and march me down to the Lou. We sit there smoking for a long while and we seem to be on-board the real Greenpeace, the death ship of the vision and the dream. After a while, one by one we begin to laugh . . . and laugh . . . and cry . . . and laugh. This is the real Greenpeace trip, sailing in a bone-boat sarcophagus across waving prairie badlands of grass, winter light pressing down through the ragged hole torn in the roof, the boat listing as though frozen in a moment when it took a wave over the bow. All we can see through the empty sockets of the windows is winter light and the soiled shroud coming down once again over sea and Earth and men with their crazy ambitions. Heaving upward in a moment of eternal sea riding, we are beached and peeling and broken, we are sitting in pews in a haunted church of our own, the wind playing the rusting engine like an organ. It is a fine long staring into the grave of our hope, it is a fine deep hurt, it is a fine dark voyage we take, Thurston, Keziere, and I, the broken wrecked old boat, broken wrecked old dream, broken wrecked old heads of ours.

When we pull away from Sand Point in the afternoon, the only people to see us off are three local freaks who stand on the dock waving at us, moments after having sadly handed down to us a sign they had painted on a plank: GREENPEACE IS A BUMER [sic]. I sit on the Picasso-like winch, riding it like a supermarket camel, wielding a cigarette holder made of a crab claw. I am stupefied and dazed – we are all dazed – and the only thing I can hear myself saying is: “Responsibility is absolute.”

The Gulf of Alaska, October.

The long blank numb retreat from Sand Point. The boat is like a museum in the late afternoon. All the energy has been spent, has blown through the rooms of the boat like the wind leaving a ruin. A museum. An air of decay. Up until the moment we finally splintered, broke, and turned around, a thrumming tension had passed through us all, a constant state of bracing oneself for the confrontations that always lay ahead. It was like bracing oneself to lift a great rock, only to step back from it and walk away. The body whines. The mind bursts loose with tracers of stored-up pumped-up ready-to-fire energy, all dissipating uselessly into thin air. The flames we stoked to hold us at the gate now come flickering like sparks that we dash in each other’s faces as we wound one another with our remarks. Humour, which has always been the truest language, now cuts like snakebites. Fineberg left the boat at Sand Point and flew back to Anchorage, saying he could do more there. Simmons decided against leaving and I was talked out of it. But it was right for Fineberg to go. “I believe I got scapegoated for raising the questions I raised,” he said. “I got kicked in the teeth for trying as best I knew how to do what we all said we were trying to do – protest Cannikin. It’s a heavy trip to work through.”

Chugging south from Sand Point, we have nothing to do but work it through. Down down down we sink, the weather rough all the way, barbs shooting back and forth, psychological wrestling matches going on at every level. Thurston is Doc Doom, making insane babbling speeches like a maniac raving in a mirror. He glides, he squirms, he plays along the jagged edges of the void wherein the mind can lose itself forever. He speaks like a phony schoolteacher, a petty official, Lucy in “Peanuts,” your most boring uncle, a suburban lady at a cocktail party, on and on through legions of stereotypes. He has them down pat because he sees through them like wraiths. He knows their every number, their every act, their every routine, and routinely he turns those blazing X-ray eyes of his on the rest of us and cuts through our acts and games with surgical precision. On the wooden fridge door is pinned a radiogram, dated October 12, 1971:

MASTER AND CREW GREEN PEACE

PHYLLIS CORMACK (AT HARBOR SAND POINT ALASKA)

THE VANCOUVER MEETING OF THE RELIGIOUS SOCIETY OF

FRIENDS SENDS LOVING WISHES FOR A SUCCESSFUL AND

SAFE MISSION. WE SUPPORT YOU IN YOUR COURAGEOUS

EFFORT TO STOP THE AMCHITKA BLAST AND TO HELP TURN

THE WORLD TOWARD HUMAN GOALS.

MARGARET LORENZE CLER.

Across it, in ballpoint, somebody has scribbled: COWARDLINESS IS NEXT TO GODLINESS.

Moore slumps at the table, gurgling with silent wiped-out laughter. This laughter is pain. I have never seen so clearly the connection between laughter and the moans and gasps of agony – even ordinary laughter, come to think of it, people moaning and crying out in front of one another, everybody hypnotized into believing that those squeaks and huk huk huks are fun noises and everything is okay. We are into another movie, one without season or weather, without colour or shape, without aim or purpose. Do you think your vision is perfect? No. Then it must be distorted. I guess you’re right. So everything you see and believe to be true is false. It can’t be helped. Down down down like bubbles we sink.

Then, as we approach Kodiak, a motorboat comes out to guide us in and a crowd stands on the dock with a big sign saying THANK YOU GREENPEACE, and people are waving and cheering, and there, perched at the very of the dock, grinning up at us through his ragged dog-hair beard, is Rod Marining, the non-leader of the northern lunatic fringe of the Youth International Party, better known as the Yippies, shaking his head, wearing an old weather-beaten leather jacket, tape recorder slung over his shoulder, headphones around his neck. “Boy, I don’t know about you guys!” he yells. “You look weird – you look like spooks, man! You really do!” All along, it has been one of the finer fantasies of the voyage that Marining will suddenly show up, riding a whale or sitting on the deck of a passing fishing boat. For Marining, the year has been an endless spiral of busts, demonstrations, border blockades, near-riots, and hassles with the cops. That is the regular routine of a Yippie – one day liberating land about to be grabbed by real estate sharks and setting up a people’s park, a few days later protesting French nuclear testing, the day after that constructing a twelve-foot joint of marijuana to be passed around to the crowd at a mass smoke-in – but in spite of that busy summer, Rod has managed to show up for almost every meeting of the Don’t Make a Wave Committee. At one point he even tried to buy his own little boat in which to sail to Amchitka. His plan was to levitate the island, cast voodoo spells on the bomb, broadcast an appeal for help to Namor, Prince of Atlantis, call in Aquaman, and pull a host of other mad Yippie media tricks. He had painted the big peace and ecology symbols on our sail and had worked furiously at various joe jobs in the hope that he might come with us. But some members of the Committee had opposed it. Right to the moment when the boat pulled away from the dock at Vancouver, Marining was there, yelling to us as we chugged away, “Wait! You’ll see! I’ll be on the boat! I just know it, man. See you later!” I, for one, have not doubted for a minute that somehow, sometime, against all odds, Marining would end up on the boat.

And here he is at Kodiak, grinning away, and now there is a spare bunk, and at least one vision is not yet smashed – Marining’s mystical vision that he will board the Greenpeace. We are heading in the wrong direction, but he’ll be on-board. It turns out he flew to Prince Rupert after we left, betting that somebody would get too seasick to continue and leave the boat at that point, whereupon he’d come aboard. When we didn’t stop at Prince Rupert, he flew back to Vancouver and took part in border blockades. Then he hitchhiked to Seattle, took a plane to Anchorage and hitchhiked from there to Kodiak, arriving just in time to stir up publicity and organize a welcoming committee. It took a certain amount of guts to hitchhike across Alaska, where only a year ago a hippie was beaten up so badly he lost both eyes. Naturally we take Marining aboard.

We spend three days in Kodiak, attending public meetings and giving speeches against Cannikin. Coast Guard types lay little presents on us, and the police chief sends us an Alaska flag to fly alongside the Greenpeace flag. A local Greenpeace Committee gets set up, local liberal press people come down to cover the event, anti-Cannikin feeling is everywhere, the police chief raises a toast to us at a dinner being held in our honour (our honour? What’s going on?), and Marining sits there in his calm serene spaced-out fashion, nodding and smiling at the Chief of Police. Alaskan congressmen and congresswomen and a woman senator show up at the public meetings, and we descend from the pure crystalline heights of an international life-or-death protest to a troupe of party politicians making speeches. Again and again Bohlen gets up in front of a room packed with Alaskans and, as tirelessly as an actor on Sesame Street, explains the dangers with every letter of the alphabet, starting with A for arms race, B for bombs in general, C for Cannikin in particular, D as in Doomsday, E for environment. . . . Right about here, sick to death of listening to Bohlen go through the whole song and dance of educating people about the obvious, I am forcing myself not to jump up and yell, “F for fuck the bastards!” I settle for heckling him with in-jokes that can only be understood by the crew. The Alaskans don’t get the jokes. They just frown and look uncomfortable that one of these good guys is such a weirdo.

A piece of graffiti on the wall of the Kodiak meeting hall is so appropriate that I want to shout it aloud to the audience, mainly local politicians, teachers, concerned citizens, concerned parents, idealistic youth, journalists, and members of the Alaska Mothers’ Campaign Against Cannikin: SOME PEOPLE I KNOW ACT SO FUCKED UP, THEY NEED TO BE SHOT. Then a round of receptions and another meeting. The Greenhawks find themselves in the home of a Gestalt therapist whose wife is throwing the I Ching for Thurston as Cormack sits in a plush chair, sipping wine, surrounded by incredibly beautiful young women, mostly teachers, social workers, and psychiatrists. There on the wall, our host has tacked up a truth:

Whatever has been, has been

Whatever must be, shall be

Whatever can be, may be

Whatever I was, I was

Whatever I must be, I will be

But whatever I am – I am

We find out that shortly after the incident with the Confidence, both the Coast Guard and the Navy issued orders forbidding any of their men to fraternize with us. The brass imposed fines on the entire crew of the Confidence, and three junior officers – the three who had been on the launch? – were demoted. But nobody would take their jobs, so they had to be reinstated. Oh, the American military machine is in a state of disarray.

Now we are out on the Gulf of Alaska, swinging more than 200 miles out from land, toward Juneau, where the Governor of Alaska is reported to be waiting to greet us as a gesture of solidarity with the anti-Amchitka forces. Potentially this is an important political move, as it may put more pressure on Nixon to cancel the test. The waves are coming up high and the grey pastes of cloud that flew away from us along the horizon yesterday are backing up now and bearing down on us like dark bruises, their sails rimmed with throbbing flares. “See them clouds up ahead?” Cormack said when they were still running away. “That’s the storm that’s just passed. It’s moving away about seventy, maybe eighty miles an hour, and we’re just poking along about nine knots behind ‘er. Wal, long as she keeps moving that way, we’re okay. Nuttin’ coming up behind us so far as we know. Only thing we have to worry about is if them clouds up ahead turn around and start headin’ for us. We’re pretty far out. Cape St Elias is about, wal, pretty near 250 miles over that way. . . .” Marining just stood there smiling serenely, seeming to hear what Cormack is saying even though the headphones are still fixed firmly over his ears and we knew he was listening to the Joe Cocker version of “With a Little Help From My Friends” recorded at Woodstock.

Marining bugs the skipper something awful. When he first came aboard and sat down in the galley with the headphones on, Cormack took one look at him and snorted, “What’s that? A spaceman?” Absolutely right on, John! Marining is a spaceman. A very spaceman. After only two nights at sea, Cormack ordered him out of the radio room. “Goddamn goony bird! Sleeps there on the floor ‘stead of the bunk. A man can’t goddamn move without tripping all over that goddamn goony bird lying there like a big stupid bug with goddamn space things on his head.” If some of the rest of us are a bit hard for Cormack to take, we are solid citizens in comparison to Marining. To top it all off, he has one startlingly dark brown eye and one seashell-glittering grey eye. You can go quietly mad talking to him, for if you look him in the brown eye, he is one person, but if you shift your gaze slightly to look into his grey eye, he is another person. He knows perfectly well what an advantage that gives him over other people. Just by staring back at you he can break your grip on certainty and even sanity, depending on how strong your grip was to begin with. Marining is weird, all right – too weird for Cormack. He has taken to defending himself in the most devastating manner – by looking back at Cormack, not saying a thing, just letting his two different eye-personas have their effect. Now he says, “Getting a little rough, ain’t she, skipper?” Cormack ignores him and keeps his eye fixed on the sky. He’s jittery. Keeps rubbing his china and muttering to himself. I am tempted to ask him, “Is this fuck-all, John?” But the old boy doesn’t look like he’s in much of a mood for wisecracks. Down in the galley, Moore is saying, “Cormack’s really uptight. We must be in for it. Oh Jesus.”

Bohlen has recovered his vital impish quality. Metcalfe has stirred from his bunk and is looking out through the open door over the poop deck, lime green water washing like a flood from a broken dam across the open space between the forecastle and the battenclaim. “That figures,” Thurston mutters. “If there was any time when we’d get killed, for sure it would happen on the way home. Fuck around. We won’t even get to be heroes.” There is such perverse logic in that comment that I start to think, yeah, this is probably it. Once we were actually retreating, we were all in such a rush to get back home that we had pressured Cormack like hell to speed it up. Maybe he was tired and fed up too. Whatever the reason, he decided to take a little chance. Now that the Gulf is being swept by winter storms, he should have avoided going out into its deeps. We could have followed the Inside Passage all the way back, skipping from the lee of one island to the lee of the next, always within sight of coves where we could take shelter.

We took that approach once between Sand Point and Kodiak. Cormack pulled into a cove beside a little island to duck out of a squall, and four other Canadian fishing boats had holed up there as well. All the skippers knew each other and they yakked over their radios and exchanged gossip and rumours. A few crewmen from one of the other boats came over in a punt and gave us some skin books in return for a bottle of wine. The wind cried like a giant gull, and gusts smacked the waters of the cove, making the sail go whap and the whole boat lurch. The anchor was down and some of the other boats had even let down their stabilizers. Like wet animals we cowered together, five bobbing chained boats in the crying wind. Late in the afternoon, a voice crackled through the radio. One of the boys hadn’t found his way out of the open water yet. There was a held-back thrill of horror in the man’s voice: “Nuttin’ on the radar yet. Maybe she ain’t workin’.” Then one of the other captains here in the safety of the cove would call out through the skrawks and ssssssssts of static: “Wind changed yet?” Sssssssst . . . oooooweeeeeeeee. “Not much. Still nor’west.” Urp whurp whurp ooooooweeeeeeeeeeee. “Took a green one over the stern there. . . .” Sounds come through the radio like saw blades in slow motion, notes so high they hurt. Half a dozen of us crowd up in the radio room, Metcalfe taping the whole thing. Birmingham explains that that’s really bad news, taking a green one over the stern, because the ass end’s not built to handle the impact of that many tons of water hitting right on her. Oyn oyn oyneeeeeeiiiiiii whirn whirn whirn.

“Any change in that wind yet, Hank? You should be picking up Cape Seal any minute.” Eeek eeeeekk ssssssst.

“Ask him if there’s any change in depth yet.” Sssst.

“Hank? Hank? Y’hear me?”

Eeeeeiiiiiiii eeeeiiiiii yi yi yi orrrrrrrrrrrrrr. . . . “Loud and clear. Over.”

“John says what’s your depth? If you’re where he figures, it should start getting shallow fast.”

Urp whurp whurp sssssssssssssttttttt. “Still ‘bout seventy fathoms. No, wait, she’s changin’. Round fifty now.”

“Okay, that’s good. Cape Seal should be just about dead ahead in a couple of minutes.”

It took hours to guide in that lost boat, the Sleep Robber, tension spitting through the storms of static, the bird-cries of the wind, the whap of the sail. By morning, the storm had let up enough that Cormack could up anchor and make a break for Kodiak.

And now we are out in the open ourselves, 250 miles south of Cape St Elias, in about 3,000 fathoms of water, midway between Kodiak Island and Juneau, no sheltered little coves to duck into, and the storm that swept the Gulf is rolling right back over us. We are starting to take green ones ourselves, and the water is beginning to smoke. Up in the Penthouse we have to hang on with both hands, and so much water has splashed in through the port doorway, which keeps banging open, that even the guy at the wheel goes slipping and sliding around. Sometimes when you cling to the wheel with all your strength, you find your feet on the port wall – the boat is tipping over that far. Nobody can hold the wheel for more than half an hour at a time. There is nothing languid about the Phyllis Cormack now. We plunge down the sides of waves like a hundred-ton surfboard, and no longer are we lifted magically on the back of the next wave. The bow smashes the onrushing wall like a battering ram. With each crash, the whole boat shudders. “We’re starting to torpedo,” Bohlen announces, his voice shivering with that alive feeling that blooms in the face of death. Cormack isn’t making any more jokes. We are finally in actual trouble, the wind coming across the hunched shoulders of legions of grey waves in eighty-mile-an-hour blasts. One moment the windows in front of the wheel are translucent ectoplasm, the next they are grey nothingness as we tunnel through a forty-foot mountain of solid water.

Cormack takes the wheel himself and refuses to give it up. He slaps his great belly against the wheel to hold it steady while he grapples for a single spoke with his tree-roots of arms. Then, with a lurch like a man swinging a sledgehammer, he yanks the wheel this way, and that way, and harder that way. Grunt. Wham. Heave. “Gotta watch fer the freak ones,” he says between grunts. “They’re the ones that come up like a pyramid. Like that over there – all green. One of them comes up under the bow a certain way and she can flip ya right over. Hup! Uhhh!” The impact of the waves is like being hit by boulders being hurled from below and massive boot-kicks to the hull. “It’s cat and mouse now,” says Cormack, his eyes scanning the sea for freak ones. He kicks the port door open and sticks his head out into the whistling whining crying keening wind to see whether she’s changed direction. He tries plowing straight into the waves, but we are torpedoing. Then he hauls her over to the left and tries taking them at an angle, but we nearly get caught in a couple of those green pyramids that lunge up with no warning. One of them explodes into the sky just off the bow, rattling the boat like a tin can full of dimes. For just a few seconds it feels as though we have left the water and are skidding crazily on ice, then we tumble off, and back into the water. The ocean has transformed itself into a tangle of vast twisting sinews, crushing everything in its path.

Out on deck it is another planet. The air is a baying moaning thing that comes slapping at our faces and smacking our bodies. Metcalfe has become Ernest Hemingway, sitting quietly and sipping his coffee while shells from Krupp cannons crash around him. Bohlen breathes like a man in an icy shower, gasping with the terrible ecstasy of it. Simmons has dug in like a bulldog. When Cormack has to check the engine, pump out the bilge tanks, eat, or crap, Simmons takes his turns at the wheel even though he is being thrown around like a rag doll. Thurston plays Beethoven and Tchaikovsky at full blast on Marining’s tape recorder as waves smash against the plexiglass galley windows. Down in the engine room, Cummings rides on a canvas camping chair in front of the typewriter, furiously tapping out descriptions of the storm:

As the sea built up around us, perceptive Cormack watchers began to sense a subtle change not in his habits, but in his attitude. He still dozed for an hour, had a cup of tea, walked the bridge, looking, sniffing, sensing. But now there was an alertness about him that belied his years and his weight. He seemed to be tuning himself in to the elements more finely than a radar beam on a foggy night. One after another, the crew took their turns at the wheel and tried to follow John’s instructions to “keep ‘er lined up with the wind.” Gradually the sway became a lurch, and then an intricate trapeze of down-right-left-up that turned ship and crew into absurd pantomimes of themselves. Clothes on their hangers swung out like a rubber chorus line, frozen for one, two, three seconds in a horizontal kick before snapping back against the bulkheads. Bodies were lifted half out of bunks then thrown back as if in contempt. Dishes clattered in the galley, turned into a sauna by a suddenly sloshed teapot. On the bridge, the watch hung onto the wheel, trying to keep it and him from being thrown by the tilt. Still, John mostly looked, sniffed, sensed. The hills of water turned into jagged mountains that would suddenly froth. Then, green water over the bow . . . the sign that the situation was getting worthy of concern. The ship had developed a tendency to reverse itself, to turn around and go broadside into the waves. At that point, Cormack took over the wheel. . . . The man and his ship have become compatible to a degree seldom seen in conventional marriages. His circumference is almost exactly that of the hatches to the engine room and the bridge, his eyes are attuned to every squeak and murmur that should be there and every click that shouldn’t, his feet innately know every board and ridge from wheelhouse to rope locker. . . .

Moore, Darnell, and Keziere have pretty well retreated to their bunks. Birmingham hurries back and forth between the engine room and the Penthouse, having incomprehensible conversations with John about the bilge tanks and the state of things down in the hold. Marining puts on his nylon flight jumpsuit, slaps his headphones over his ears, and climbs out into the wind and waves to groove on the storm. Out on the bow, he and I get hold of a thick rusty chain, then ride down like birds, down, down, gargantuan surfboard ride through green flinging-up mountains and streams of smoky foam, the whole boat crashing down like a truck dropping from a cliff, and just at the moment when the bow torpedos into the wave, we pull ourselves up in the air and swing from the chain, while a whole ocean of water smashes over the bow, whipping our faces and hands in stinging bites. If we are going to die, it is going to be a wild ride of a dying. Marining passes me the headphones between waves, and through the wind and thundering drum rolls of rising water I am listening to Ten Years After doing their super-adrenaline-fired Woodstock version of “I’m Going Home.”

And now a dolphin breaks the water like a grey knife, leaping out just ahead of the bow, flipping itself into the air and looking at us along its dark duck-like mouth. Didn’t I read somewhere that dolphins sometimes rescue shipwrecked men floundering in the water? That they swim alongside ships in distress to give sailors moral support? “Hey, dolphin!” yells Marining. “Wanna borrow the headphones?” The dolphin flips into the air again, as if to say, so it’s an eighty-mile-an-hour wind and fifty-foot waves – so what? It’s heaven. Don’t let the fear of death get in your way! We whoop and holler like kids playing on the most incredible carnival ride ever invented, and Cormack watches us from up in the Penthouse, where he is still fighting the wheel. “Pin it with his stomach, spin it back, pin it,” writes Cummings. Moore hangs on to the edge of his bunk with one hand and tries to concentrate on Lord of the Rings and all of us think about the damn two-by-four down in the engine room, wedged between the big Atlas engine and the hull, possibly the only thing that is keeping the engine from toppling over.

Now the bilge tank pump breaks down and the engine room starts to flood. Cormack is down there cursing and working furiously to fix it. The engine splutters and farts and coughs, making the same noises it made just before it conked out completely a month ago as we crossed the Gulf of Alaska. It was flat calm then, so when the engine went, we just bobbed around like an apple in the swells until Cormack got it fixed. But now. . . . Darnell wants to know if everybody has said their morning prayer to the engine god.

“How do we watch out for the freak ones when its gets dark, John?”

He shrugs. “It’s a checker game now.”

There he is, agile as a cat, a grey-green toque jammed down on his head, torn purple and grey plaid shirt with shredded sleeves, big leather boots, white whiskers prickling out all over his jowls, concentrating like a concert pianist, poised like a surfer, legs bent and braced, steak-sized hands wrapped around the spokes of the wheel, and the years fall away. The flapping old man is gone, and there is a muscular barrel-chested Hell’s Angel of a sea captain, brawling his way across the screaming barroom. It is a sight that makes me want to cry out, “Come on, John!” cheering on the Lone Ranger or the guy leaping into the sky from the phone booth.

But as the hours wear on, even Cormack’s cast-iron body begins to tire. He knows that he can’t solo this one – sooner or later he’s going to have to trust one of these damn amateurs with the wheel. Near the end of the third day out here, after thirty-five hours of the boat chopping away at the waves like an axe, wind like a moan from the void, everybody battered and bruised from being thrown against walls and cupboards and ladders and bunks, enough of us have pumped Cormack for information that we can imagine getting through the storm alive if our skipper passes out or collapses from exhaustion.

That night, the ocean kicks the shit out of us. Cormack rests fitfully in his bunk, getting up again and again to give Bohlen and Simmons fresh instructions. “Feels like she’s running stronger this way now, take her over a little more to the left. . . . Keep her there steady ‘less you can’t keep the wheel up, then let her fall a bit the way she wants to go and try to ease to the right for a while. Sometimes you can kind of zigzag your way through.”

By morning, only five of us can still get out of our bunks. Cormack gives the order to swing her around, and Bohlen and I tackle the wheel together, using all of our combined remaining strength to hang on as the boat cracks like a whip and bucks and throws herself over so far that the water looks to be running directly below the port door. If that damn door bangs open now, we’ll drop right into the ocean. Incredible long seconds of being shaken like dolls by the convulsing of the wheel as the old boat bounces like a stand-up punching bag with a weight at the bottom. The boat almost – almost – goes over, but doesn’t, and once we have steadied the wheel again, we are running with the water and an entirely new motion has taken us over. Now we have a following sea, a sea that lifts you like a leaf and wafts you this way and that, raising you lazily, then settling you down as if it were lowering an infant into a bathtub – except that the bathtub is riding around like a horse galloping in slow motion. Ahead of us a path appears like an abandoned trail, and all we have to do is keep the nose of the boat pointed into the trail, while the wind sweeps past in jet streams as low and fierce as a winter blizzard. We can just barely detect a slight absence of streamers directly ahead, like a windprint of the boat – our wake lies ahead of us and we are driving back into it.

“Gotta watch this kind of thing,” says Cormack, looking no less uptight than when we were plowing head-on.

“What’s the danger now, John?”

“Wal, you get a following sea like this and you don’t have to work so hard, if you know what I mean. But you can get caught nappin’. Them waves are still out there, even if you can’t feel ‘em so much on account of we’re not joggin’ into ‘em any more. But the stern ain’t built like the bow, and you don’t have to take too many of ‘em over the stern before she starts to break up.”