This chapter examines the architectural work of Wenceslaus Hollar (1607–77) in terms of its scale of representation, focusing on the role this opus has maintained in relation to architecture and the cities of the seventeenth century. It concentrates on the significance of small-scale images and argues that the craft that Hollar brought to England was critical for the development of architecture and urban design in London in the aftermath of the Great Fire. The chapter argues how early modern architectural representation brought together rich and nuanced cultural, geometric and empirical understandings of scale. The connection to late seventeenth-century urban design (and the work of Robert Hooke in particular) will be addressed, as it is still a lacuna in the architectural history of London.

After leaving Prague at the age of twenty, etcher and engraver Wenceslaus Hollar lived in Strasbourg, Frankfurt and Cologne. According to the note presented on his best-known self-portrait, drafted by Jan Meyssens, Hollar was ‘initially drawn to miniature painting’ but was dissuaded from studying it by his father, who wanted his son to pursue a career in law. The young man settled for the graphic art of etching instead. As a son of a high-ranking official and a member of the Bohemian nobility, Hollar could have had access to the works of artists assembled by Rudolf II in the collection at Prague Castle. Rudolf, the Holy Roman Emperor (1552–1612), who was patron to Tycho Brahe and Johannes Kepler, had built the northern wing of the palace for his collection. The collection included works by Dürer, the Bruegels, Van Leyden, Paul Bril, Tintoretto, Veronese and the cabinet of curiosities that later became the model for other collections of a similar kind.1 The King of Bohemia was one of the first monarchs to have private collections of art in the sixteenth century. The Kunstkammer (modelled in part on the Italian studiolo) was itself the microcosm of the visible world that was supposed to direct its owner towards a virtuous life.

At the beginning of the seventeenth century, Prague was probably the most exciting European capital. It was the meeting point between people working in the arts and the emerging mathematical sciences. In this context, Wenceslaus Hollar had developed a strong sense of visual culture and an understanding of the specific visual demands of his time. This is evident in his focusing on the medium of prints, which included the portrayal of diverse phenomena, where his love for precision could thrive. The sources upon which Hollar drew included the miniature paintings of Joris Hoefnagel (1542–1600) and his son Jacob (1575–c.1630), Netherlandish artists employed in Prague, the art of Jan van de Velde, and the works of Rembrandt and Jacques Callot. The Prague thirteenth-century school of miniatures was another important stimulus on Hollar, as were the works of Albrecht Dürer, whom Hollar had imitated from an early age.2

Documentary, detailed and lyrical, Hollar's images are seen as containing an aura of empathy. The small scale has probably contributed to this perception. A small drawing or a print becomes an object of intimacy that can be taken everywhere. It is a personal item, unlike big tableaux, which are about places, large rooms, light and display.

Unease in regard to the old, and restlessness in respect of new investigations, were reflected in the seventeenth century's attitude, which had increasingly attached greater value to observation and reflection in contrast to flights of subjective vision. In other words, this was the time of transition of attitudes and mentalities (mentalités).3 In his own manner, Hollar pioneered the emerging change and visual experimentation.

The position of the visual arts was altering across Europe. Eight years senior to Hollar, Spanish painter Diego Velázquez (1599–1660), known for his experimental enquiries into the nature of painting, is a case in point. His painting Las Meninas (1656) has been central in determining attitudes about the nature of pictures, their role in society, in relation to individuals and different social strata (Foucault 1991). In a single gesture of going behind (and around) the canvas, Velázquez has opened up a new territory for the art of painting, taking the ars pictura from the realm of resemblance-making into the domain of reasoning.

Richard Pennington, the author of the most recent and complete catalogue of Hollar's work, argued that Hollar had been involved in exploring his interest in space, three-dimensionality and depth throughout his professional engagement (Pennington 1982). The liveliness and the depth of his images come from the fact that even when working at large scale, such as complex constructions of panoramic city views, Hollar completes his work with closely observed and clearly defined detail (Brothers 1998: 4). This move is not a grand gesture as in Velázquez's Las Meninas, but it makes a vital link to the viewer. Hollar seems to be guided by the desire to transmit his view most directly to the observer.4 In a century notable for the establishment of art collections, botanical gardens and scientific collections of animals and plants, the demand for systematically drawn and engraved images became pervasive. The images reproduced in folios and books became essential in spreading emerging connoisseurship and knowledge. Having been part of medieval illuminated manuscripts as hand-drawn meditative images, miniatures became prominent again – as prints.5

The epistemological role of these miniatures needs to be acknowledged, as they were linked to the category of microcosm that was essential in controlling the exuberant proliferation of similitudes that governed knowledge in the sixteenth century and first half of the seventeenth century. It is likely that Hollar had understood his images as this kind of microcosm – a claim that can be supported by the nature of his framing, his precision and by his Prague background. For Hollar, it was essential that the relation of this microcosm to the macrocosm of the world (including architecture) should be preserved accurately, as it was a guarantee of the otherwise unstable limitless knowledge. As such, the quality of the miniature drawings and prints by Hollar marked the limit of knowledge and pushed the confines of its possible expansions.6

Hollar's landscape series began with Prague and its environs. These views were compact: the surrounding scenery acted as a frame, a curtain enclosing the small-scale representation of the urban form in the distance. The views of Strasbourg followed, becoming more developed and expressive, conveying Hollar's softness of articulation in unfolding the length of the view.7 The small landscape drawings that precede the prints are the intimate expressions of Hollar's personality, as drawing was his first medium and the creative mode in which he attained perfection.

Hollar's compositional counterpoint between the city in small dimensions and the overall portion of landscape is characteristic. He had adopted the technique employed by the painters (‘painter's algorithm’), where distant parts of a scene were drawn before the parts that were nearer – repoussoir – a technique that produces a feeling of depth.8

Commentators agree that the nine years spent in Germany were important for Hollar's personal development, and in particular the period spent at the Merian studio.9 Comparing the quality of Hollar's work before and after his stay there, it is evident that this employment greatly contributed to the enrichment of Hollar's technique. The practice required fast, accurate work of high quality, and not individuality or artistic inclination (Pav 1973: 104). By taking part in this enterprise, Hollar acquired the topographical techniques for panoramic city prospects and bird's eye views.

Hollar incorporated these techniques into his own style of representation. It gradually became highly original and new, combining topographical knowledge with an artistically driven manner of representation comprising curiosities, softness and compassionate interpretation.

Hollar had travelled up the Rhine to Mainz, Delft and Rotterdam. The Düren drawings that followed are considered among the best examples of Hollar's work. They evoke emotional harmony with a landscape based on realistic study. The large view of Cologne (1636) represents in many respects the peak of Hollar's achievement in topographical drawings.10

The emergence of small-scale detailed representations should be considered beyond their artistic context. They need to be viewed within a broader field of vision, including the discipline of optics and related experiments that characterised seventeenth-century scientific developments. One such milestone, which increased the possibilities for magnification, was Kepler's advancement of Galileo's telescope in 1611.11 Although single-lens magnifiers had been in use in the mid-fifteenth century, it was the invention of the microscope that had revealed previously hidden miniature worlds. The seventeenth-century developments of the telescope on the one hand and the microscope on the other had extended scientific knowledge and inspired the scrupulous illustrations of the structure of plants, animals, birds and insects as produced by artists such as Hollar. In this respect, it could be argued that the seventeenth century decisively addressed the question of scale (Edgerton 2009: 155–68).

Travels (including Hollar's own) and the increased movement of people contributed to the circulation of new ideas and to the ‘sharpening of vision’. The educational ‘touring’ around Europe was not only about gaining knowledge and acquiring crafts, it was also about training the eye. Hollar had learned how to observe the differences between states and principalities, and how to adjust the manner according to the dominant mores.

Hollar's involvement in England began in 1635 when he met the Earl of Arundel, who was on a diplomatic mission in Europe. The English diplomat was an aspiring art collector, who, after seeing Hollar's work, made him an employment offer. The earl planned an etched catalogue of his collection and needed a skilled engraver, as the art of etching had not been fully developed in England (Brothers 1998: 4).12

Hollar arrived in London in 1636 and was soon to acquire many commissions.13 His English patrons included the Earl of Arundel (a member of the Privy Council), Charles II and the Duke of York, later King James II. Hollar had benefited professionally from these connections, leading him to secure royal favour around 1641, following the death of Van Dyck, who had been the court painter.

Hollar's work had been gaining ground, as global trade was shifting towards the Atlantic nations. London became the place of exciting encounters, exotic goods and coffee shops.14 The critical enquiries and debates that were previously taking place throughout Europe were now to be found in London. They had prompted the establishment of scientific assemblies such as the Royal Society (1662), dedicated to the promotion of science and knowledge. Hollar had famously etched the Royal Society history book front page designed by John Evelyn.15

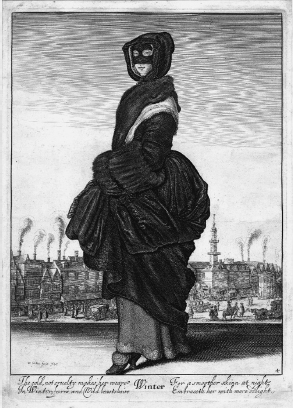

Hollar's interests were wide and included the representation of animals and plants, as well as ladies’ fashion and significant events of the time. This made Hollar quite original and unique. His The Several Habits of English Women from the Nobility to the Country Woman, 1638–40, is an exceptional visual study into female costumes that resulted in the production of rendered masterpieces of this genre. Hollar's Theatrum Mulienarum (1643) is equally attractive. Women were portrayed in their local costumes as they came from across Europe: England, the Netherlands, France, the German principalities, Bohemia, Italian cities as well as Greece, the Balkans, Turkey and Persia. Notable are The Four Seasons, representing women in the clothes designed for each season. Here the women were situated in a specific spatial/urban context: Winter famously stood on a pedestal with the London Royal Exchange in the background (Figure 1).

Figure 1 Winter, by Hollar, from The Four Seasons, 1643, with the Royal Exchange, London in the background. (Pennington. 609, 253 x 180 mm)

This kind of artistic representation stands in contrast to the more ‘masculine’ aspect of Hollar's work on maps, as in the well-known 1644 map entitled The Kingdom of England and the Principality of Wales. This map was reputedly used by Cromwell during the Civil War as he regarded it the best and the most detailed of all maps of Great Britain. One of the clues for this variety of interests is the relentless eye of the miniaturist. It seems as if Hollar's eye cannot stop absorbing while it penetrates into the entirety of the fabric of seventeenth-century life, people, places, animals and plants.

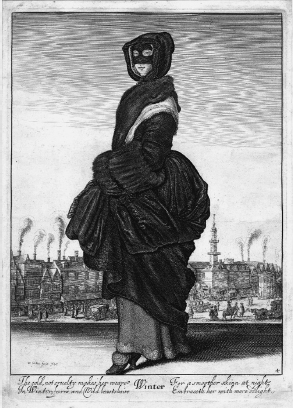

Hollar was fascinated by London, its topography, its prospects on the Thames, as well as by its surroundings, such as Islington, Lambeth, Surrey and Greenwich. Several of the smaller London views show the quality of Hollar's delicate line, notably the six Islington Views and the View of London from the Top of Arundel House, while the long view of Greenwich rendered in 1637 became paradigmatic for its choice of viewing point, which remains relevant for subsequent architectural schemes up until today (Figure 2).16 The Richmond view depicts the royal party in miniature scale. Views along the Thames from Whitehall and Lambeth Palaces are precise and revealing of the historical edifices along the Westminster and Strand area.

Figure 2 View of London from Greenwich by Hollar, 1637. (P. 997 145 x 831 mm)

Figure 3 Long View of London from the Top of Southwark Cathedral at Bankside by Hollar, 1647.(P. 1014, 6 plates each print 462 x 392 mm)

Hollar's best known view is that of seventeenth-century London drawn before the Great Fire, originally published by Cornelius Danckerts in Amsterdam in 1647, while Hollar was in exile. This view is a construct made of a number of smaller views that Hollar had kept as drawings, assembling them together into an outstanding composite presentation observed at a 180° viewing angle from the top of St Mary Overy, presently Southwark Cathedral (Figure 3).17 This iconic view of London is probably Hollar's most copied and disseminated work.

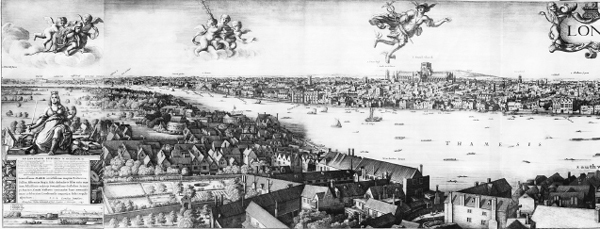

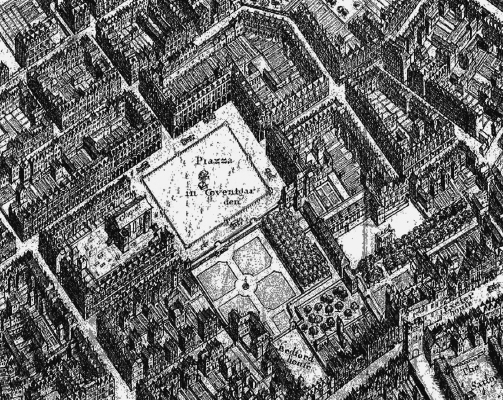

Although Hollar drew on small sheets of paper (depending on genre they ranged in size between approx. 50 x 70 mm and approx 250 x 500 mm), his printed city plans and views also appeared on a grand scale. Hollar's (c.1658) West Central District of London (only known from two copies, one held in the British Museum, the other in the Folger Collection, Amherst) is a good example of the ambitious combination of the practical aims of a map and an attractive delineation depicting the houses and gardens of the city (Figures 4 and 4a). London squares such as Covent Garden (Figure 4) and Lincoln's Inn Fields are rendered from above, thus complementing the separate terrestrial views of the same squares (Figure 5). The view is full of details (Figure 4a) etched in Hollar's style, combining a well-structured bird's-eye view with architectural features (Hind 1972: 15). This view is wide, with vanishing points beyond the scope of the print, thus giving the appearance of an axonometric. The composition could thus be seen as a precursor of axonometric representation.

Richard Godfrey has argued that West Central District of London could have been a sample piece for a larger view of London that Hollar was planning to do in the 1660s, when he had issued a flysheet of Propositions Concerning the Map of London and Westminster. This map was supposed to be of a significantly bigger scale (10 ft x 5 ft) and was to express ‘not only the Streets, Lanes, Alleys, etc: proportionally measured; but also the Buildings (especially of the principal Houses, Churches, Courts, Halls; etc) as much resembling the likeness of them, as the Convenience of the room will permit’ (Godfrey 1995: 25). The ambition, the quality of the rendering and the available evidence would suggest that Godfrey could have been right, implying that West Central District of London is an unfinished masterpiece. Overall, Hollar produced 2,733 pieces, including numerous representations of English churches, monuments and cities published for the folios of William Dugdale and John Ogilvy (Pennington 1982).

Figure 4 West Central District of London, bird's-eye view.(P. 1002, 338 x 451 mm)

Figure 4a Detail of the Covent Garden area, c.1658.

Figure 5 Lincoln's Inn Fields perspectival view by Hollar, 1660s.(P. 998A, 85 x 389 mm)

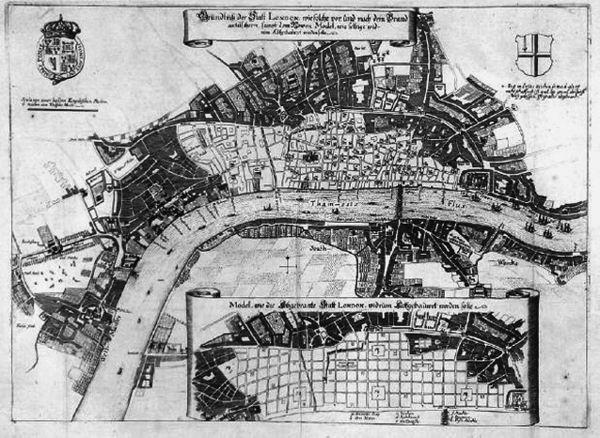

The lifelike renderings of London before and after the fire made Hollar an invaluable source of information for the City of London authorities as they responded to the claims in the aftermath of the disaster. City officials instructed Hollar to make an exact survey of the city as it stood after the fire. Hollar's maps were thus the definitive record of the Great Fire, representing the burned-out districts as white spaces (Figure 6).

As many as 436 acres of the medieval city had gone, but the fire also created an opportunity to make a new grand, planned city with better amenities. Charles II was determined to create a city that would reflect London's status. Within days of the fire, five proposals appeared, including the well-known scheme by Christopher Wren, the less known by Robert Hooke, the proposal by Richard Newcourt to rebuild each parish as a single block, Valentine Knight's city plan ringed with canals, and the courtier and diarist John Evelyn's scheme comprising a series of elegant boulevards.

Figure 6 Hollar's plan of London showing burned areas of the City in white, 1666. (P. 1004, 268 x 345 mm)

The scientist, polymath and architect Robert Hooke proposed a modern grid layout with gently meandering streets.18 The organic layout of Hooke's scheme looked as if it had been inspired by the microscopic images as presented in his 1665 book Micrographia – a beautifully produced edition, seminal in its use of drawings as an integral element of scientific rhetoric.19

The king favoured the scheme by Christopher Wren, whose scheme was closest to Charles's vision of a European-style grand capital with piazzas, long straight avenues and magnificent views. Despite the king's wishes, all the grand plans were abandoned as there were no funds to compensate the owners of the city plots. Instead, individual owners had to be allowed to rebuild their own houses, and the old medieval street plan was kept in its outline. This approach favoured Hooke's flexible and meandering cellular grid, which was able to negotiate new buildings with the old plan. This was also one of the reasons why Charles II had asked Wren and Hooke to jointly oversee the rebuilding of the city (Cooper 2003).

A closer examination of Wren's and Hooke's work shows how they used Hollar's prints and drawings to further their own designs. Wren's drawings, such as the amalgamated depiction of St Paul's Cathedral kept at the British Museum, comprises the rendering of St Paul's as executed by Hollar, while his positioning of the Greenwich Observatory and the Royal Naval Hospital seem to have been derived in relation to and along the axis of symmetry of Hollar's Greenwich view, respectively.

Hooke is known for his engineering and scientific skills; the fact that he was an architect with a good visual and aesthetic sense is often forgotten. Hooke had an artistic education with Peter Lely, and is the author of drawings that have recently been traced back to Hans Sloane's eighteenth-century collection. Hooke was neglected for a long time due to his dispute with Isaac Newton (Hunter 2010: 251–60). Architectural scholarship on Hooke is scarce, but it is certain that Hooke was Wren's main collaborator on the Monument, the Greenwich Observatory and St Paul's Cathedral.20 Hooke's precise structural considerations and understanding of materials were applied in the building of the dome.

Even if Hooke's and Wren's grand original projects were not carried through as conceived, their planning, surveying and the overall vision were incorporated in the principles of urban design as negotiated with the City of London. Jointly, they contributed to the emergence of a temperate but significant redesigning of the city after the disaster. The rules for this subtle transformation to the urban fabric that were established by Hooke and Wren have carried on until the present day. These regulations enabled London to transform itself several times, without having to endure major ravaging such as had happened in Paris in the nineteenth century, or in Vienna when the Ring was built. The interventions to the urban fabric negotiated by Hooke are not to be underestimated because they built upon the existing plan. The post-1666 system of regulations in urban design may not have suggested a monumental scheme, but the new design emerged in its own right. The novel buildings had to be different, made of more sturdy materials, fire-resistant and structurally sound. The medieval wooden structures of limited height and span were replaced. In doing so the buildings were morphologically altered as the lengths, heights and other ratios were subjected to the required structural changes. The urban design components were kept in terms of their overall character and disposition – the ‘neighbourliness’ of their elements, indicating the transformation of a topological kind.21 The new topology was based on Hooke's interpretation of the old city plan that was superimposed and correlated with the newly required safe distances between the buildings. The documentation that was used in this process was provided by Hollar. In his diaries, Hooke (1935) refers to Hollar on several occasions, stating that he had appreciated his ‘scientific method’ and the scale of ‘100 to an inch’, which had reportedly been favoured by Hooke himself.22 The selection of the ‘right’ scale was therefore an important criterion and an indication of a particular approach.

Hooke's contribution to the rebuilding of London deserves reappraisal within the history and theory of architecture. The subtle topological transformation that was implemented in the City of London depended upon the precision of mathematical, artistic, practical and experimental knowledge that Hooke possessed. While Wren had an overall vision for the metropolis, acquired while travelling in France, Hooke's proficiencies included expertise in drawing, measuring, handling experiments and understanding materials. Wren depended on Hooke in respect of these skills.23 Hooke was thus not an ordinary assistant: he was intellectually equal to Wren and an architect in his own right.24 Hooke negotiated the design with the owners of the plots while complying with Wren's (and his own) future vision of the new city. The subtle geometry of Hooke's originally proposed plan with its organic cellular structures most probably continued to guide his vision and his negotiations.25 The author of Micrographia, who used to sit behind the microscope and observe microorganisms and cells, was now designing urban structures on a scaled-up macro level (Figure 7).

The present configuration of the City of London is therefore a product of this complex vision, negotiation and scaling-up. This skilful leap contributed to the shaping of an organic urban morphology based on Hollar's unassuming but detailed depictions, and brought to life by Hooke's interpretation, understanding and foresight.

It is possible to conclude that Hollar's 1637 long view of Greenwich had introduced a new aspect of vision to London. This was followed by the other views produced by Hollar that gave London its iconic set of aspects anchored largely along the Thames. Hollar's etchings won this acclaim because they were, according to Evelyn, ‘copied from life and hence more deserving of appreciation than those which rather depict chimerical curiosities and things non-existent in Nature’ (Evelyn 1995). Evelyn, like Hooke, Wren and other connoisseurs and scientists of the time, collected Hollar's prints. Moreover, Hollar and Hooke shared a profound curiosity on the level at which they approached the world. They both observed phenomena in minute detail with a curious, sensitive and insightful eye. Hollar explored, loved and celebrated the miniature scale format in his images (Hunter 2010: 251–60). Their most powerful legacy is the versatility and resourcefulness that, among other things, stimulated the production of architecture and urban planning.

The miniature's ability to communicate to different people, disciplines and discourses sheds new light on the nature of architectural design, knowledge and debates in the late seventeenth century. By virtue of their compactness, empathy and adaptability, drawings and prints by Hollar circulated widely. They increasingly populated the emerging scientific texts, thus becoming intimate with the realm of the new sciences. They grew to be part of the world of learning, underpinned by the same epistemological ground as the scientific writings of the time. In turn, they began to mould, change and determine the basis of scientific texts. In this way, illustrations by Hollar acquired and affirmed their position of consequence in relation to knowledge, architecture and urban planning of London and beyond.

Figure 7 The image inserted into Merian's plan is Hooke's plan for London, c. 1670.

1 During the Thirty Years War, works of art were looted by the Swedes in 1648. The last rebuilding of the castle was by Queen Maria Theresa in the eighteenth century.

2 The works addressed here are Hollar's Christ, Madonna, self-portraits and landscapes.

3 This is in the Annales sense of the term.

4 John Aubrey, one of Hollar's three biographers (with Evelyn and Vertue), had traced Hollar's love for drawing to his early age, when Hollar was a ‘precise delineator of the scenes’ (Aubrey 1898). Detached and disciplined, he was an excellent illustrator despite the fact that he had never had a systematic training.

5 The term miniature comes from the Latin minium, red lead, used in a picture in medieval illuminated manuscripts; the early codices have been miniated. The generally small scale of the medieval pictures has led to an etymological confusion of the term with minuteness and to its application to small renderings. Source: www.enotes.com/oxford-art-encyclopedia/miniature (accessed November 2010).

6 On this matter, see more in Foucault (1991: 32).

7 This kind of print dates back to Dürer and his followers, the so-called German ‘little masters’ (Brothers 1998: 3).

8 Repoussoir (French, ‘to set off’): a figure or object in the foreground is ‘set off’ from the principal scene, thereby increasing the sense of depth. Source: www.enotes.com/oxford-art-encyclopedia (accessed November 2010).

9 This period in Hollar's life remained unclear. Pav has corrected some errors. He has clarified Hollar's movements inside Germany (1627–36) and has traced Hollar's development from the early drawings of the Stuttgart period to the more mature works of Cologne in 1636 (Pav 1973: 96).

10 Hollar's representations are mainly executed as etchings, although the difference between the etched and the engraved is imprecise in seventeenth-century sources. Hollar himself was inconsistent, according to Van Erde (Van Erde 1971: 4). Vertue states that all Hollar's works were executed by etching, adding that he has well adapted that manner of engraving to them (Van Erde 1971: 142).

11 The important events at the time included the invention of Galileo's telescope in Venice. This was an improvement of the systems developed in the Netherlands (see Steadman 2001). Galileo published the work, including his observation on the sun and the moon, provoking anger within the Catholic Church, followed by the 1633 trial. His Dialogue was outlawed for centuries.

12 For more on Arundel, see Springell, who corrects Aubrey's and Vertue's report. Springell maintained that Hollar went to Merian's studio directly after Prague (Springell 1963: 136–7). However, the argument made by Pav about Hollar being with Merian in 1630–31 is more convincing.

13 Hollar's role in respect to Arundel is not entirely clear. He was a member of Arundel's household and as a nobleman maintained his independence. Arundel's life circumstances were exceptional. Both his grandfather and his father had come to disastrous ends. Arundel travelled to Italy in 1614 with Inigo Jones as a companion. In 1616, he publicly repudiated Roman Catholicism by embracing the Church of England and in 1621 he was appointed Earl Marshal of England. See Griffiths and Kesnerova (1983: 29).

14 The seventeenth century saw an increase in the scale of international travel and commerce, opening up of colonial markets, establishing enterprises such as the East India and South Sea Companies.

15 In 1662, a group of scholars from Oxford (Christopher Wren, Robert Boyle, John Wilkins, Robert Moray and William Brouncker) proposed a society ‘for the promotion of Physico-Mathematicall Experimental Learning’. This body received its Royal Charter from Charles II, and The Royal Society of London for the Promotion of Natural Knowledge was formed.

16 Even today, the views from this point are considered when granting permission to the tall buildings in the City of London. Source: Tavernor, Robert. Scale Conference, Canterbury, November 2010.

17 The original prints can be found at the British Museum, British Library and the Museum of London; the composition was subsequently reprinted and copied by various artists.

18 The diversity of Hooke's activities and knowledge that gave him the nickname ‘Leonardo of London’ has presented a problem in attempts to assess his life and work. He was a Curator of Experiments to the Royal Society.

19 This scheme was mentioned by Marsh and Steadman (1971).

20 Recent scholarship includes the works by Lisa Jardine, Alan Chapman, Paul Kent, Michael Hunter, Michael Cooper.

21 On topology, see Marsh and Steadman (1971).

22 Already in the seventeenth century, Hooke had a vision of the decimal scale.

23 This was the reason why the king was in favour of Hooke. Another reason was that, politically, the king needed a good relationship with the City of London.

24 Hooke designed the Bethlem Royal Hospital (Bedlam) in Moorfields in 1675, and Ragley Hall, Warwickshire. Hooke was the Gresham Professor of Geometry. The City, having appointed Hooke as Gresham Professor and having preferred his plan for rebuilding to that of their usual surveyor, sought from him a vital contribution during the years 1667–74 (Cooper 2003).

25 This was intuited by Marsh and Steadman. In regard to Hooke's own scheme, the authors stated that Hooke had ‘mapped his ideas of the city into the cell of the sponge’. They thus credited him with designing the first cellular city. Hooke had recognised the ‘cell’ as the smallest unit of life, thus introducing the term into its usage in biology (Marsh and Steadman 1971: 33).