In his eighteenth-century treatise on the art of cabinet-making, Thomas Chippendale included several practical offerings on the derivation of the column orders and the good use of perspective drawing in what was a surprising slippage between architecture and the decorative arts. Architecture, he wrote, was ‘the very Soul and Basis of the Art [of cabinet-making]’, and, although architecture was still clearly distinguished from the craft of domestic furnishings, architectural theory was beginning to be captured and applied in new ways (Chippendale 1754: preface, 1). A generation later, in a handbook by Thomas Sheraton, knowledge of architecture had become fully integrated into the theory of furniture-making, and drawings of chairs, buildings and architectural mouldings were commonly juxtaposed within a single didactic engraving (Sheraton 1802: 309, 321; Figure 1).

By the time that Walter Gropius issued the Bauhaus manifesto of 1919, this affinity between art and craft had been solidified. Furniture-making and architecture were no longer separate disciplines, as they were now subsumed together under the guidance of the ‘architectonic spirit’ (Bergdoll and Dickermann 2009: 64). Now, as architects concerned themselves increasingly with smaller works as well as buildings, the ability to design among various sizes of construction became embedded within the very notion of architectural knowledge. An interesting point of departure, then, in addressing the scale of works in architecture might be demised from the favoured pastime of Chippendale, Sheraton and, now, countless architects: the design of furniture. Unlike a building, which promises only peripheral contact between the body and the architecture, furniture often joins with the body directly, placing architects intimately in contact with their own architecture. A sometimes painful test of the Gesamtkunstwerk, whereby the entirety of architecture, as ‘total design’, would encompass a paradigm for modern life, furniture is often an anatomical challenge to the spiritual ascendance of the body through reason alone. Frank Lloyd Wright problematised the matter quite succinctly when he lectured to Princeton undergraduates in the autumn of 1938. In discussing the integrity of organic architecture, certain complications nevertheless emerged:

I soon found it difficult, anyway, to make some of the furniture in the ‘abstract’; that is, to design it as architecture and make it ‘human’ at the same time – fit for human use. I have been black and blue in some spot somewhere almost all my life from too intimate contacts with my own furniture.

(Wright 1987: 45)

Figure 1 Drawing by Thomas Sheraton, from Thomas Sheraton, Cabinet-Maker and Upholsterer's Drawing-Book, London (1793).

Here, the transference between the various sizes of Wright's constructions is taken as an ethical problem, where architecture is a direct challenge to that which is ‘human’. In complaining about the incommodious nature of his own furniture, Wright reveals one of the fundamental difficulties embedded in thinking of large works in the same way as small ones. When furniture is considered as a kind of miniature architecture, unable to be revealed as a world in itself, there is a problem of scale. For Wright, the scaling between various objects of practice is reduced to a static system of measure, where both small and large works are judged in the ‘abstract’: that is, in their specific adherence to the principles of the organic. However, in the argument proposed herein, scale is not a static relationship of proportional measures, relying on universal principles. Played out in the realm of human situations, rather, scale relies on the ability to interpret and transfer certain modes of thinking between various sizes of works. In this way, scale may be thought of as a realm of practice where the character embodied in the design of large and small works may be transferred between each other. As in the practice of architecture every situation is unique, scale emerges as a key mode of thinking in the transference of ethical thinking between projects of various sizes and scopes.

It would not be possible to revisit such a notion of scale without the erasure of the traditional disciplinary distinctions between architecture and cabinet-making that played out during the style debates of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. The rise of historicism opened the door for small objects of cultural production (such as furniture) to lose their previous grounding in craft tradition and gain increasing intrigue as objects of speculative knowledge. The treatises on cabinet-making by Chippendale and Sheraton highlight this trend from the point of view of the crafts, where the science of perspective, from architectural theory, becomes an integral supplement to traditional craft knowledge. The amalgamation of furniture and buildings under ‘architecture’ parallels this larger push toward general theorisation within the field of cultural production. Here, the writings of Gottfried Semper provide a poignant point of departure for architecture, as his nineteenth-century tome, Der Stil, is still regarded as one of the most comprehensive attempts at the theorisation of cultural production under a universal system of practical aesthetics.

Since the publishing of his Die vier Elemente der Baukunst in 1850, Semper had worked to upend the prevailing theories of architecture as originating in the imagined primitive hut, favouring instead a mode of understanding based on human action or making. In Der Stil, the meticulous study of furniture provided a valid method for exploring ‘primitive’ or ‘natural’ architecture, as was demonstrated in his famous musings over style in Assyrian stools (Hvattum 2001: 537–46). In establishing an evolutionary connection between the origin of architecture in craft motifs and monumental architecture as exemplified in Greek temples, Semper relied on the separation of the tectonic realm into movable and immovable. Here he offered a new characterisation of furniture as a kind of portable tectonic that pre-dated architecture:

tectonic root forms are much older than architecture and had already in premonumental times … achieved their fullest and most marked development in movable domestic furnishings. From this it follows, according to the general laws of human creation, that the monumental framework as art-form was necessarily a modification of what tectonics had developed on its own in its earlier objective.

(Semper 2004: 623, emphasis in original)

This division between architecture and furniture is a potent example of how the traditional authority of craft knowledge was being replaced by architectonic theory. Now, furniture could be removed from its cultural situation and theorised within a larger notion of architectural production. Because large and small were no longer differentiated by their disciplinary relationship, such as architecture or cabinet-making, the distinction between movability and immovability allowed Semper to subjugate cultural objects of all sizes under a more general aesthetic theory. No longer taken as products intrinsic to cultural production, the study of these objects thus became a valid field of inquiry for architects. Unlike traditional cabinet-making, where the craftsman and the client entered into a situational dialogue surrounding the work's particular needs, circumstances and concerns, the making of furniture was now appropriately ‘designed’ (possibly by an architect) before it entered the hands of the craftsman.

Semper's work was part of an intellectual tradition that participated in the unification of the arts under various theories of universal knowledge. In the German tradition, one of most striking was certainly the well-espoused theory of the Gesamtkunstwerk, if only for its encompassing every aspect of spiritual, intellectual, and productive life. Popularised by Richard Wagner in the Art of the Future, the ideal of the Gesamtkunstwerk sought to unify the various domains of art as a bastion against the nihilism of the modern, fragmented, industrialised existence. Here, Wagner formalised the principles of ‘the great Gesamtkunstwerk that comprises all artistic forms, in order to use all individual forms as a means, to annihilate them in order to arrive at the Gesamtpurpose, that is, the absolute, immediate representation of the perfect human nature’ (Bryant 2004: 156–72). Architecture would lead this transformation, as led by early German Modernists such as Peter Behrens (Bryant 2004: 156–57). Taken in the context of the Gesamtkunstwerk, scale is a mode of transference whereby the total, Hegelian Idea finds itself manifest in small and large works, with the expectation that spiritual transcendence will accompany the life of a totally controlled, harmonious environment. In design strategies that embrace abstract, non-situational unity, scale is a mode of transferring between small and large works, whereby the synthetic idea is manifest in different measures as related to a unified continuum of experiences. A building, chair or object is thus ‘small-scale’ or ‘large-scale’ depending on its measured relationship to a formal concept, often relegating the primacy of human accommodation to a secondary role.

The Viennese architect Josef Frank protested against the difficulty of foregoing the fundamental differences between large and small, however, writing in 1923 that he was ‘of the opinion that anyone who has the desire to rest his posterior on a rectangle is in the depth of his soul filled with totalitarian tendencies’ (Frank 1981: 215). The rectangle, belonging to buildings, is contrasted with the human body in repose, conjuring an image of utter contempt towards human accommodation. By invoking the straightness of the rectangle, Frank highlights the danger of abstract, speculative thinking as acted out in the practice of small objects made for human accommodation. In this context, architects, seduced by rational theories and methodologies, could easily lose touch with the original notion of furniture: to accommodate the body. This would be tersely satirised by another Viennese, Adolf Loos, in his short essay ‘Poor Little Rich Man’, where we learn of the disastrous consequences of the complete and totally designed existence (Loos 2003: 18–22). As with Wright's musings over the difficulty of making furniture fit for human use, Loos exposed the fundamental opposition of total design approaches to the pragmatic affairs of daily life. Ultimately, for our purposes, Loos's essay magnifies the question of scale as an ethical concern. If large and small are unified at the expense of human accommodation, then there is an ethical problem. It is not difficult to uncover disturbing instances of architects putting total design into practice: Wright designed dresses for the women who dwelled in his houses, a natural extension of the total transfer of domestic life under the premises of the organic, for example; and Behrens, in an effort to release workers from the hegemony of industrial production, dictated that they should be exposed to the salvation theme from Wagner's Parsifal once every hour (Bryant 2004: 162).

As the control of furniture design was increasingly distanced from those who actually made it, the creep of speculative thinking into the production of furniture became a fundamental ethical consideration. Total design strategies, as pointed out by Loos and Frank, tended to neglect the situational nature of practice and the necessary consideration of size in understanding the relationship of the work to human use. Scale, at this point, had lost its potential to act as an imaginative space between large and small works, and had been reduced instead to a system of measures based on a universal design concept. Such a tension between the abstraction of design and the design of abstraction seems present still today, and perhaps an overly formal understanding of scale is embedded in this hostility. In returning briefly to older notions of practice, however, perhaps we may discover alternative modes of conceptualising scale as a unifying principle between the design of various sizes of works.

One common bond between the production of various sizes of works in architecture might be what Aristotle called phronesis: the principal intellectual virtue of adapting universal principles to concrete situations. Often translated as ‘prudence’ or ‘practical philosophy’, phronesis denotes how the architect is able to deliberate properly upon particular situations encountered in daily practice. It is a sphere of non-formalised, yet coherent, knowledge that prepares and guides the architect along the shifting circumstances of practice (Aristotle, Nicomachean Ethics: VI.viii.9). As an intellectual virtue, rather than a capability or aptitude, such as judgement, phronesis governs one's actions toward ‘the good life in general’, and includes not only practical shrewdness but also that which is proper and improper, which Cicero and Vitruvius would later call decorum (Garver 1994: 41–3).1 Phronesis relies on a keen knowledge of practical affairs, but is not wholly pragmatic.2 It is rational, yet cannot be justified through logical or universalising propositions; it exemplifies the problem of mastering practice without being mastered by it (Hariman 1991: 26–35; Garver 1987: 14–15).

The rubric of phronesis was espoused in classical theories of rhetoric, most of which find their origin in Aristotle's Rhetoric. Here, Aristotle provided a concrete programme of how one may act prudently within the shifting and circumstantial realm of oratory, and it would not be difficult to imagine how such an approach could serve as a possible model for a broader interpretation of practice. In Book I, he elucidates what would be one of the most lingering guides in all of classical rhetorical theory: the three ‘proofs’ of good oratory – ethos, pathos, logos. Taken together, the three edicts could be envisioned as a kind of rhetorical programme, as a guide for judgement within the realm of various scales of practised activities. Briefly stated, ethos originates in the character of the speaker, in his or her virtue, one might say. Aristotle claims that one possesses ethos when the ‘speech is delivered in such a manner as to render [the speaker] worthy of confidence’. Pathos is that element of a speech that persuades through the arousal of the emotions, ‘for the judgments we deliver are not the same when we are influenced by joy or sorrow, love or hate’. And finally, according to Aristotle, a persuasive speech depends on logos, or logical argument, which is the interpretation of the speech through one's faculties of reason (Aristotle, Rhetoric: I.ii.4–6). Ethos, then, acquires primary importance for Aristotle, with the pathos and the logos taking on a subordinate role to the larger question of how the work of oratory projects the ethical character of the author.3 This is why phronesis is Aristotle's chief intellectual virtue – because, in its ability to determine one's actions within contingent and shifting circumstances, it governs the ethical life in general (Aristotle, Nicomachean Ethics: II.vi.15). Aristotle's rhetorical programme is a demonstration of how architecture as a practised activity might be subsumed under the general principles of phronesis.4 As ethos/pathos/logos is a guide for situational judgement rather than universal principles, the three proofs offer a concrete example of how non-formalised thinking may be transferred between works of various sizes. Such a transference occurs through a keen awareness of how the object is situated within its context of large and small. Scale is a mode of thinking that relies on prudent thinking and facilitates the transference between large and small without the kind of abstraction present in formal design strategies. In the same way that a scaled drawing facilitates an imaginative inhabitation of the unseen work, scale enables an embodied connection between small and large objects of practice.

It is in the situational nature of practice that scale emerges as the crucial link between size, ethics and meaningful building. An object taken out of situation is an ethical problem, which is why Frank and Loos satirised the tendency of total design strategies to remove works from the realm of human situations. However, with the notion of scale offered herein, one may subvert the hegemony of the synthetic idea and recapture the malleable, situational theorisation that leaves open the deliberative reality of human affairs, desires and reason. With a model such as Aristotle's ethos/pathos/logos, we may speak of scale as a metaphorical procedure that makes use of certain commonalities between small and large works hidden beneath their apparent visual or formal properties.

In the context of total design strategies, the allure is in the possibility of the embodiment of a singular design principle or principles within the intimacy of a work of furniture. With Wright, for example, furniture lies along a continuum from object to building, and eventually to the city, the totality of which ought to demonstrate the principles of organic architecture (Wright 1987: 73–5). In the rhetorical context, however, the possibilities are in the transference of ethos/pathos/logos, a model of invention through practice, which frees the architect from hegemonic formal principles. Furniture, from this perspective, allows the architect to perform at a small scale. As the multiplicity of decisions present in a building project are reduced significantly in a work of furniture, the architect has the ability to control all levels of design and production, should he or she choose to do so. As studies for architecture, then, they are highly productive, as one may demonstrate the principles of practice without actually producing a complex building project. It thus is a revelation of the entirety of one's character, or ethos, within a single, intensely tangible work.

As a discipline that is practised, the ethical principles exemplified in a work of architecture may be studied no matter what its size. In this way, one embodies phronesis by acting prudently through a work of architecture of any size, from silverware to buildings. The possibility of ethos/logos/pathos as a scaling procedure may be demonstrated quite well in the case of Carlo Mollino, a mid-twentieth-century Italian architect who practised within a wide range of scales. In a recollection of Aristotle's ethos, Mollino often emphasised the direct connection between the work and character of the maker, stating in one text that ‘every work of art reveals its creator; an exact image and likeness of the person who made it’ (Mollino 2007b; Brino 2005: 10). For him, each work is a synthetic response to a wide range of circumstances that often lead to unpredictable results (Mollino 2007a: 212).5 The possibility of phronesis, then, emerges as a guide for practice, allowing him to unify a wide range of works through contextual, rather than strictly formal, undertakings. In this way, a recent publication on Mollino shied away from a traditional typological organisation of his oeuvre, preferring instead to present his work by categories of ‘obsessions’: flying, skiing, photography, cars and architecture (Brino 2005). Certain formal preoccupations are no doubt detectable throughout his work, but they do not reveal themselves with clarity; rather they are veiled in metaphor. They remain mysterious to definition and open to interpretation. Even while working at many scales, he is able to subvert the total design strategies, and one clearly detects a consistency of inquiry into the virtues of phronesis through the ethical dimensions of the human accommodation. We therefore understand the work through a revealing of the synthesising context, which is the basis of phronesis and of Aristotle's ethos/logos/pathos.

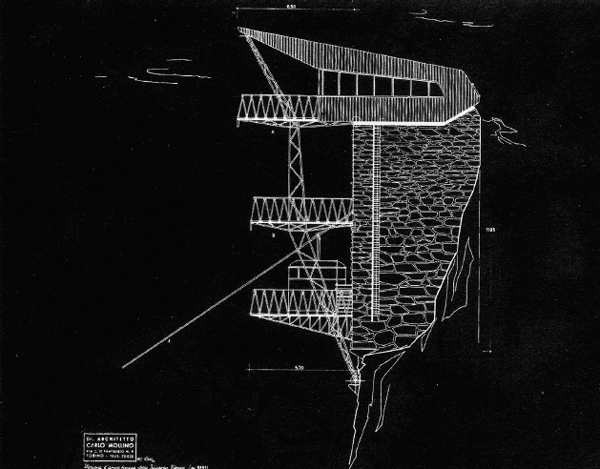

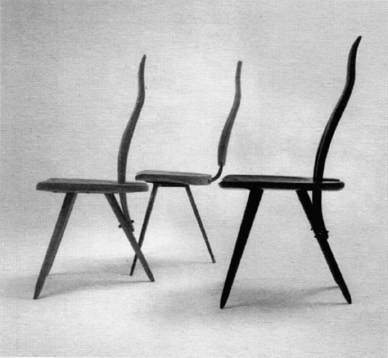

His studies of the grace and balance of the alpine skier provide a fruitful rhetorical metaphor, for example, which guided his hand among several sizes of works (Figure 2). Here one can observe how an architectural analysis of the skier's body in motion is expressed in the subtlety of the Fürggen cableway station, where the stability of the stone structure, embedded in the mountain face, is juxtaposed with the reach of a delicate steel structure. In contrasting the dynamism of the skier's body with the architectonic/vertical dashed line and centre dot, Mollino suggests a rhetorical procedure for dealing with an alpine architecture: eloquence of both skier and building resides in-between motion and stability (Figure 3). A similar practice may be observed in a work of a different size: his three-legged chair, inspired by the motion and rest of the human body while sitting. Here one imagines how a detailed attention to the balance of the body might easily have derived from his sensibilities developed in skiing, racing cars, and flying acrobatics. The combination of a narrow back along with three legs provides utmost stability among many floor surfaces; yet the careful attention to the curve of the chair back, as belonging to the body, suggests that the chair is an invitation for the sitter to presence the balance of the body within the act of sitting (Figure 4). This stands in contrast to Wright's three-legged chairs, long a matter of derision among his clients, which were viewed by the architect as an extension of organic simplicity. For Wright, the active balancing by the sitter was seen as a gentle encouragement of good bodily and spiritual posture.6 In Mollino's case, however, the chair was primarily a device of human accommodation rather than a tool for moral rectitude. Unlike chairs that are placed within the spectrum of an abstract ‘idea’, the chair for Mollino cannot be separated from its primacy as an anthropometric device. It is in this way that scale, as a rhetorical procedure rather than a formal one, facilitates the fluidity between the skier, building and chair.

Figure 2 Carlo Mollino's studies of a skier.

Figure 3 Carlo Mollino's design for a cable station.

Figure 4 Chairs designed by Carlo Mollino

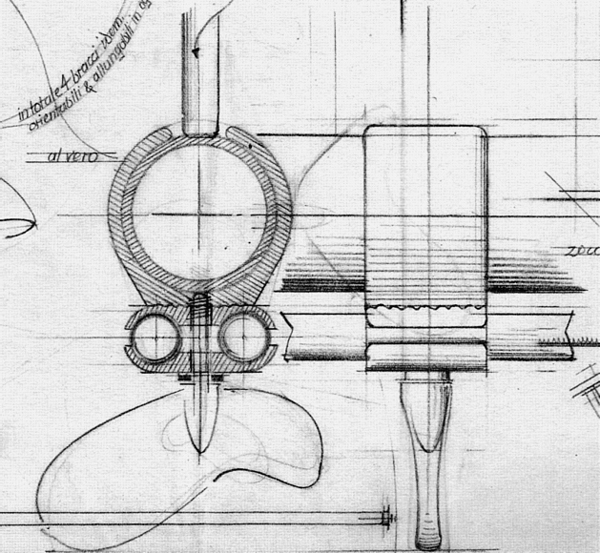

The transference of prudence between various sizes of works is activated through the metaphorical procedure of scale, as is demonstrated through the work of Mollino. Large and small are means of metaphorical inquiry into a prudent practice. All of this discussion, however, raises the question – why do architects design furniture anyway? Perhaps it is in the benefit of smallness that a work of furniture holds the potential to be an embodiment of the entire process of the construction of a building. Unlike a model of a building, which requires that one imagines a future building of a larger size, a chair is already fully sized, present and available for integration into the sphere of human activity. While the multiplicity of decisions present in a building project are reduced significantly in a work of furniture, one may still present the entirety of the poetic and tectonic realm within a single, small work (Figure 5). Mollino's thumbscrew for a brass lamp recognises formal sensitivity as well as the use of the human hand, two principles of architecture that would be transferrable to all sizes of works. As a mode of practice, then, the design of small objects is highly productive, as one can live out the principles of prudent practice without actually producing a complex building. Because one must practise in order to be better at practice, the chair or other small object is often undertaken – it shows its didactic and demonstrative purpose within the discipline of architecture.

But this does not tell the whole story. In terms of total effort, a chair appears to be a relatively simple matter compared to the construction of a building, but perhaps it is not as straightforward as it appears. Architects have often commented on the great difficulty of designing chairs, for example, since in the experiencing of a chair, one confronts the tangibility of the architecture immediately and directly.7 A chair may be touched in its entirety, providing a dialectic between that which is at hand and the demonstrability of phronesis. The chair as a small object is often thought of as more difficult quite simply because it more openly and tangibly displays its virtues. One can easily imagine Mollino confronting such a difficulty in his three-legged chairs, and, like a building project, would address these questions through drawings, prototypes and models. In confronting the complexity of chair design, we understand the transparency of phronesis, which accompanies something sized to be inhabited by the human body. A building hides many secrets among the millions of joints; yet the chair willingly offers itself to any person eager to sit in it and perform an examination of its materials and construction.

Figure 5 Carlo Mollino's thumbscrew for a brass lamp.

Compared to a building, which is immovable and large, the entirety of a work of furniture is tangible, within reach and at hand. The work itself, through a prudent practice, displays its qualitative principles no matter what the size. Scale provides a method of theorising this metaphorical transference, which occurs between large and small without becoming trapped in the formal modes of total design. Scale, as a virtuous enterprise, will continue to be a powerful aid to the imagination as long as it is not reduced to mathematical relationships of measurement, where size and scale are used more or less interchangeably. Although the process of furniture production might be a mirror of building, as remote and industrialised, the work is nonetheless ‘closer’, as one imagines that the architect had control over every word, every detail, and how they were pronounced. The confrontation of furniture design by architects seeking meaningful, ethical constructions will remain a potent and fruitful undertaking.

Notes

1 See in particular Cicero, De officiis 1.96 and Vitruvius, De architecture I.2.5–7. On the classical reciprocity between decorum and prudence, see Kahn (1985: 12–22).

2 Aristotle claims that one may excel in techne, but not in prudence. One may be either good or bad at rhetoric, taken as a techne. Prudence, however, denotes excellence within itself, indicating its status as a virtue (cf. Nicomachean Ethics, Vi.v.7).

3 The relationship of the three proofs has never been a settled matter. See, for example, Garver (1994: 109–10).

4 Ernesto Grassi offers a compelling challenge to the supremacy of philosophy over rhetoric. See Grassi (2001: 18–34).

5 ‘Le più robuste e sistematiche estetiche, e perciò insieme la critica, sono nate dal “compartimento” della poesia’ (Mollino 2007a: 212).

6 The three-legged chair was intended to encourage good posture, a moral proposition based in ‘uprightness’, both in the body and in the spirit. See Ehrlich (2003: 63).

7 The most famous anecdote is from Ludwig Mies van der Rohe, who was quoted as saying ‘A chair is a very difficult object. A skyscraper is almost easier. That is why Chippendale is famous’ (Mies van der Rohe 1957). On the difficulty of furniture in another Modernist icon, see Le Corbusier (1990: 105–21).