Four

CREATING SHAKER HEIGHTS

The Van Sweringens spent years on the design for Shaker Heights before offering properties for general sale. From the beginning, this was not just a housing development. It was a planned community creating a quality of life that set Shaker Heights apart.

The design of Shaker Heights was guided by ideals of the garden city movement that originated in England and advocated communities with extensive parks and both public and private gardens. In a garden city, population density was controlled so that residents had a sense of open space throughout their community. Streets were lined with trees, schools were placed on large plots surrounded by green space, and houses were set back to create substantial front lawns.

The architecture of homes and public buildings in Shaker Heights was also controlled. Homes were to be designed by an approved architect and conform to styles and standards established by the Van Sweringen Company. The acceptable designs for Shaker Heights houses were profoundly traditional. At a time when artists and architects were experimenting with the modern, Shaker Heights looked firmly backward to styles of the previous century. These homes offered a sense of comfort, reliability, and permanence. Buyers were assured that their investment in Shaker Heights was secure, not just because of the quality of the housing but also due to 99-year deed restrictions that promised to keep things as they are, always.

Included within the planning were municipal services and amenities that buyers expected. The Van Sweringens provided for a public school system and also several private schools. Retail stores were initially not allowed in Shaker Heights; it was to be strictly a city of homes. The need for a shopping area was addressed by developing Shaker Square in a section originally part of Shaker Heights but then ceded to Cleveland. Land was also set aside for churches and country clubs.

Advertising for Shaker Heights related back to the Shakers who had once lived on this land. As theirs was a refuge from the outside world and its harshness, so was Shaker Heights.

THE HERITAGE OF THE SHAKERS. Judging by its cover, this booklet appears to promise a historical view of the Shakers in a centennial year of 1923. In fact it is a brochure published by the Van Sweringen Company advertising houses for sale in Shaker Heights. Promotional materials often drew upon the “heritage of the Shakers” to emphasize that this community was, like the Shakers, set apart from the world. (SHPL.)

SHAKER HEIGHTS BORDERS. The initial boundaries of the village of Shaker Heights were fluid, sometimes expanding, sometimes shrinking. When a portion of Shaker Heights was returned to Cleveland for Shaker Square, the odd extension on the northwest corner was retained because Mayor William Van Aken’s property was located there. This map shows present-day borders of Shaker Heights in relationship to North Union Shaker land. (SHS.)

MARSHALL LAKE. Developers retained the two lakes the Shakers had created when they dammed Doan Brook. They added two more: Marshall Lake and Green Lake. This photograph is a view of Marshall Lake with two adjoining homes built for the owner of a drugstore chain, W. A. Marshall, and his son. It was included in the sales brochure “The Heritage of the Shakers.” (SHPL.)

NEWTON D. BAKER HOME. This house on South Woodland Road was home to Newton D. Baker, Woodrow Wilson’s secretary of war, Cleveland’s law director, and a contender for the Democratic nomination for president that went to Franklin Delano Roosevelt. Plans for Shaker Heights included mansions like this for high-profile residents as well as housing for families of more modest means. (SHPL.)

A GARDEN CITY. The Van Sweringens were influenced by the English concept of a garden city with ample green space throughout. Homes were set back from the street to create large front yards; thus, private property contributed to the public experience of the community. A garden city offered a sense of peace and serenity where residents benefited from the best of city and country living. (SHS.)

PUBLIC BUILDINGS IN A GARDEN CITY. Public buildings contributed to the experience of open space by their placement on large plots of landscaped property. Houses were also set back from the roads, conveying an expansiveness that carried throughout the community on both public and private property. Pictured here is the original Shaker Heights High School (now Woodbury Elementary School) and its sweeping front lawn. (CSU.)

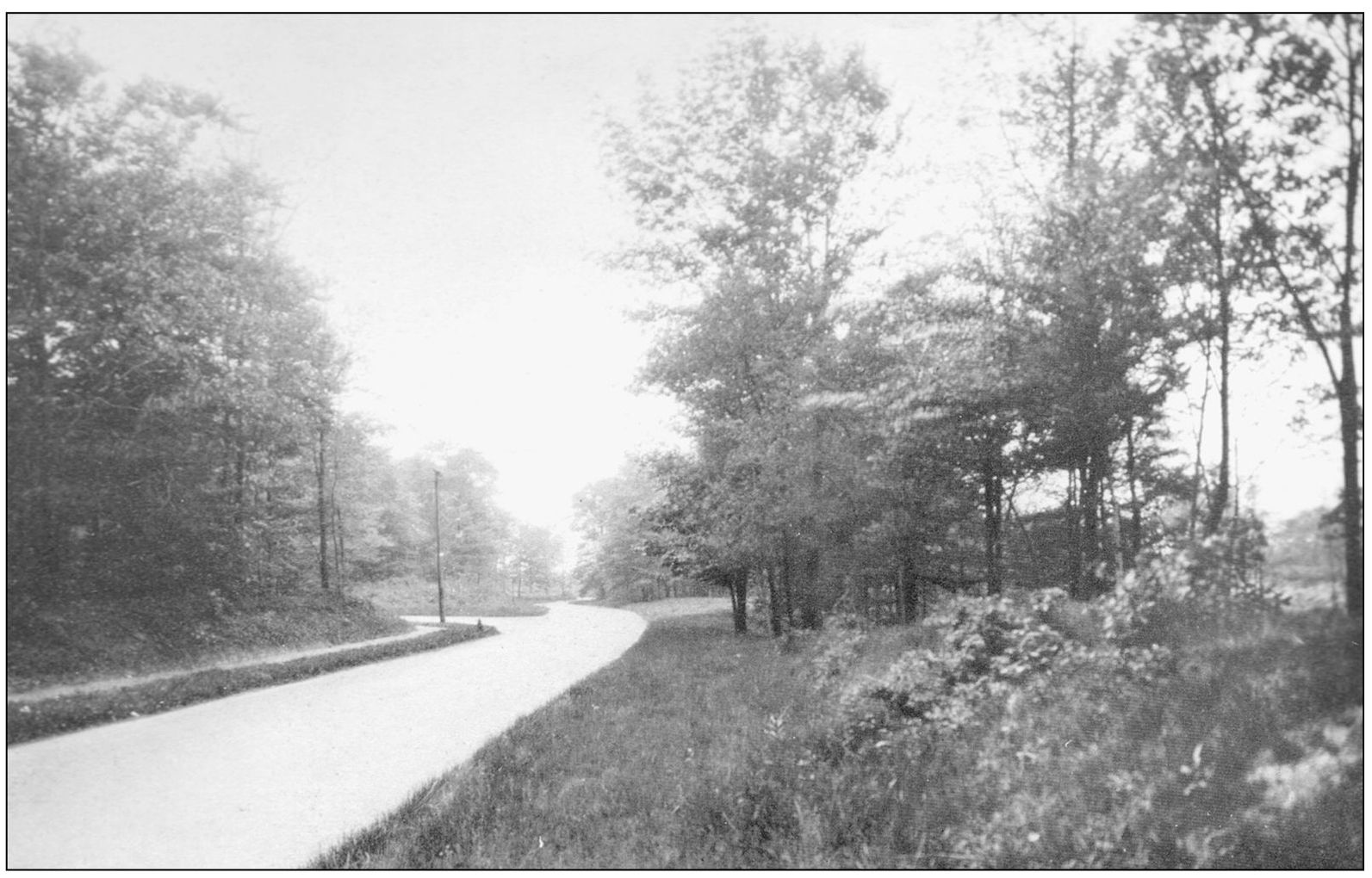

PARKLAND DRIVE. The Van Sweringens engaged the F. A. Pease Engineering Company to create the layout for Shaker Heights. Placement of roads through the city was an important factor in creating the desired atmosphere: main arteries were straight and wide to promote their use, residential streets curved making them aesthetically more pleasing as well as inconvenient to cut through, thus diminishing the traffic. (SHS.)

BROXTON ROAD HOMES. The F. A. Pease Engineering Company sent one of its partners, H. C. Gallimore, to England to study garden cities and bring back ideas to apply to Shaker Heights. Gallimore was a student of English literature, and he drew from that knowledge—as well as from an English postal directory—to name roads in Shaker Heights. (SHPL.)

MAY M. CHAPMAN. A recent graduate of Columbia University, May M. Chapman came to Shaker Heights in 1912 to serve as the school system’s first principal. She expressed her enthusiasm for helping develop schools “where individual progress would be the first consideration.” During the four years of her tenure, enrollment in the Shaker Heights schools grew from 26 pupils to 169. (SHCS.)

BOULEVARD SCHOOL. The first classes of Shaker Heights schools were held in the village hall. Shaker Boulevard School, now known as Boulevard School, was completed in 1914 and hosted classes for 1st through 12th grades. From the beginning, the schools offered innovative approaches to education such as “a special teacher for those needing extra attention.” In 1917, the board of education added a requirement, unusual for its time, that teachers be college graduates. (SHPL.)

NORTH FROM BOULEVARD SCHOOL, 1917. The roads are in place in this photograph—Southington and Drexmore Roads come together at Shaker Boulevard, and rapid transit tracks have been laid. Only a few houses are visible, but in the distance is construction on another home. Newly planted trees line the streets, and the roads are brick. On the triangle in front of Boulevard School, students in military uniform raise the flag. (SHS.)

BOULEVARD SCHOOL NEIGHBORHOOD, 1920. An aerial view shows houses beginning to fill the landscape, but there is still significant open space, such as in the oval where the school is located and the two triangular areas on either side of the oval. These were to be left undeveloped—open and green—as houses were built in the surrounding area. To the north is Lower Shaker Lake. (SHPL.)

MILITARY TRAINING UNIT, 1918. As American forces became involved in the war in Europe, German-language instruction was removed from the curriculum and military training made compulsory for boys sixth grade and up. The boys in this military training unit are posed next to Boulevard School. Some are holding bugles, others have rifles. After the war, German returned to the curriculum, and military training was dropped. (SHS.)

SHAKER HEIGHTS HIGH SCHOOL. Boulevard School served all grades until 1919 when the high school was completed. Here the new building can be seen from the intersection of South Woodland and Woodbury Roads, then brick streets. The trees that line Woodbury Road have not yet been placed, and no landscaping has been done on the school grounds. (SHS.)

HIGH SCHOOL VIEWED FROM EAST. The first levy to support Shaker Heights schools was placed before voters in 1912. It passed with 20 of the 25 votes cast in favor. A 1938 publication of the board of education noted that Shaker Heights schools spent more per pupil than any district in the area. Shaker schools became known as “private schools with public funding.” (SHS.)

HIGH SCHOOL BASEBALL TEAM. Athletics played an “important but sane” role in the Shaker Heights schools, according to a board of education brochure. The board furnished basketballs and baskets to students before the first school building was constructed, and an athletic coach was hired when Boulevard School opened in 1914. Here the baseball team in 1919 poses in front of the new high school building. (SHS.)

ONAWAY SCHOOL. The Shaker Heights school system built 10 school buildings in 17 years. This included the complex that comprised the old high school (now Woodbury School), Onaway School in 1923, and the current high school in 1931. These facilities were laid out on abundant lawns with tennis courts, fields for hosting sports events, and the community rose garden. (SHPL.)

LUDLOW SCHOOL PUPILS, 1931. The school board encouraged teacher freedom and creativity by eliminating administrative tasks and rigid schedules. Instead, teachers were encouraged to bring their best skills to the classroom—and in the process encourage a comparable freedom and creativity in their students. Teachers who developed successful innovative approaches shared these with others on the staff, working together to create a dynamic environment for learning. (SHPL.)

VISITING THE MUSEUM OF ART. From their inception, Shaker Heights schools taught students more than the fundamentals of reading, writing, and arithmetic. They also called for “development of appreciations and understanding of things of beauty and social significance.” Enrichment experiences such as art classes, music instruction, and field trips were included as part of the curriculum. In this photograph, students visit the Cleveland Museum of Art. (SHCS.)

DISCOVERING COAL GAS. Education in the Shaker Heights system featured a hands-on style of learning that encouraged participation and direct experience. The students learned by doing. Here a junior high school science class experiments with coal gas. The enrollment in Shaker Heights schools had grown to 4,200 when this photograph was taken in 1938. (SHCS.)

UNIVERSITY SCHOOL RENDERING, 1928. The Van Sweringen Company reserved land for three private preparatory schools in Shaker Heights. University School, a school for boys founded in 1890, established its campus in Shaker Heights. Hathaway Brown School and Laurel School, both girls’ schools dating back to the late 1800s, also built facilities in Shaker Heights during the mid-1920s. (CSU.)

LAUREL SCHOOL. The institutions serving the community—schools and churches—were often established in advance of other settlement in the area. Here the Laurel School campus is seen with most of the surrounding area still vacant. In the years following, housing filled in the open space shown here. (CSU.)

HATHAWAY BROWN MAY QUEEN COURT. Hathaway Brown School traces its history to 1876 when “afternoon classes for young ladies” were initiated in Cleveland. The private day school opened its facilities in Shaker Heights in 1927. In this 1931 photograph, the Hathaway Brown May Queen and her court appear on the school’s outdoor stage. (CSU.)

SHAKER HEIGHTS COUNTRY CLUB, 1928. The Van Sweringens provided amenities in Shaker Heights to attract those they hoped would buy homes in this community. The Shaker Heights Country Club opened in 1915 on land donated for that purpose. Property was also made available for the Canterbury Country Club. (CSU.)

RIDING CLUB. Four women ride horses through Shaker Heights in 1931. The Van Sweringens established a riding club, and bridal paths crossed through the community. The availability of horses not only provided another service to residents but also underscored the message that this was a rural area, far from the pressures of the big city. A move to Shaker Heights was a move to the country, and early residents reported that their friends thought they were crazy to move so far away. (SHPL.)

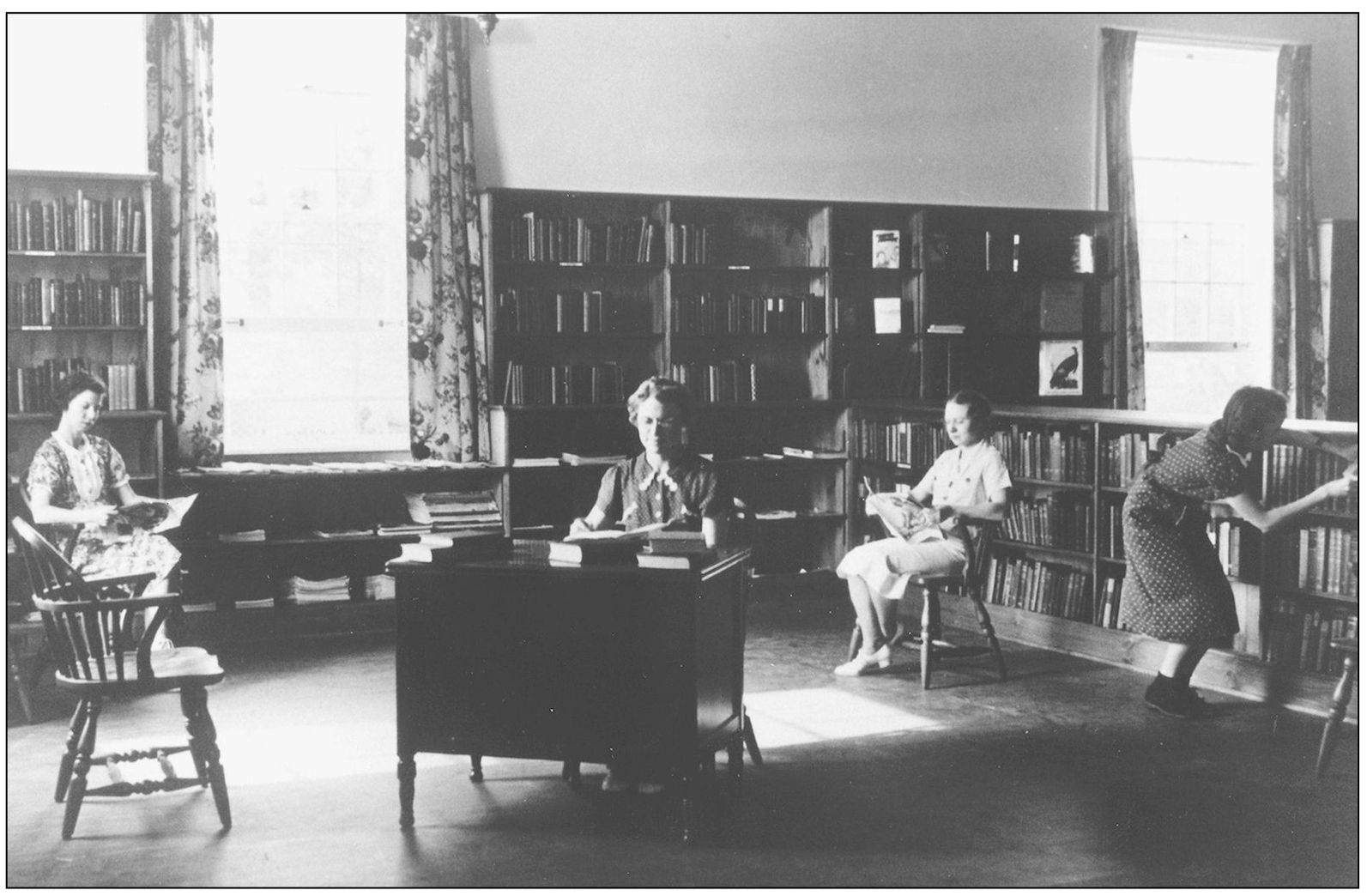

SHAKER HEIGHTS PUBLIC LIBRARY. The library had its beginnings in 1922 when a room in Boulevard School was set aside for that purpose. In 1937, the board of education created a school district library that moved into newly constructed quarters on Lee Road. This photograph shows the library staff and patrons soon after moving into the new facilities, which were designed to feel comfortable, like a living room. (SHPL.)

LEE ROAD LIBRARY. In 1951, a new building was completed that served for over 40 years until the library moved to the former Moreland School building. This building then became the Shaker Heights Community Center. The Bertram Woods branch was named after a railroad engineer whose will left assets to whatever library served his home farm, which had been located near Warrensville Center Road and Fairmount Boulevard. (SHPL.)

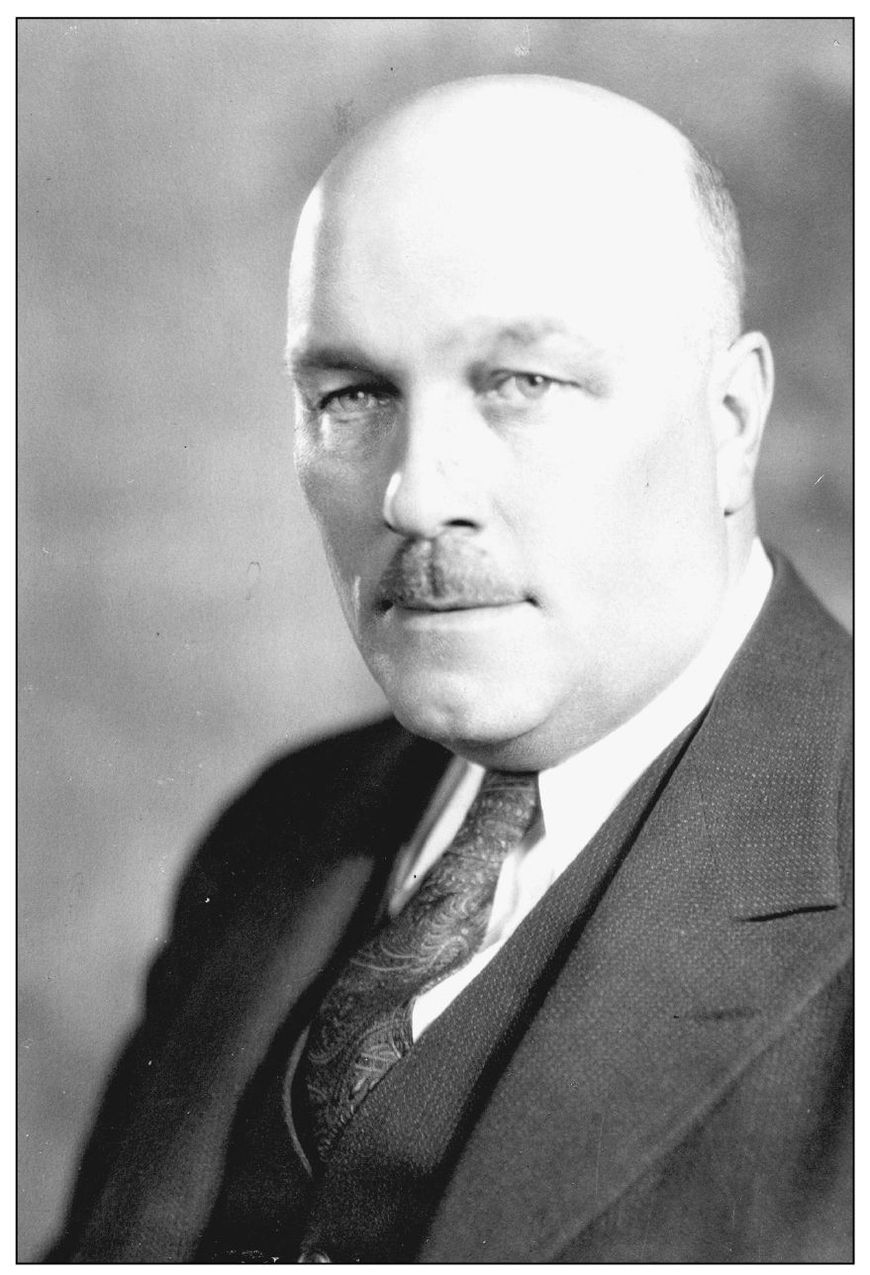

MAYOR WILLIAM J. VAN AKEN. As boys, William Van Aken and the Van Sweringen brothers were newspaper carriers together, delivering the Cleveland Leader. Later the three were close associates in developing Shaker Heights. William Van Aken became mayor in 1915, an office he held until his death in 1950. (SHPL.)

CITY HALL UNDER CONSTRUCTION, 1930. The design of public buildings—government offices, schools, and churches—was consistent with the architecture of the houses. As houses in a neighborhood were to fit together, the public buildings were to be suitable for the neighborhoods where they were located. The architect for city hall was Charles S. Schneider, who also designed Plymouth United Church of Christ and the rose garden. (SHPL.)

CITY HALL FRONT ENTRANCE. Shaker Heights was still officially a village when the new structure to house local government offices was built. But village officials were confident of continued growth, inscribing the term “city” in stone over the front entrance before it was actually true. Fortunately, the subsequent census showed that the village of Shaker Heights had reached a sufficient population to be designated a city. (SHPL.)

VAN AKEN BOULEVARD. After Mayor Van Aken died, Moreland Boulevard was renamed in his honor. Displaying the sign announcing the new name in this 1951 photograph is Julie Krausslich, secretary to the mayor. Van Aken and Shaker Boulevards are the two main thoroughfares planned by the Van Sweringens to parallel the rapid transit tracks. (SHPL.)

FIRE DEPARTMENT. As the village developed, municipal services were added. The first police department consisted of a single village marshal hired in 1912. A fire department was added in 1917 with eight paid firemen and a truck. In 1922, members of the Shaker Heights Fire Department pose for this photograph. (SHPL.)

THE CITY’S MOST DANGEROUS INTERSECTION. A 1935 newspaper photograph identified this as the most dangerous intersection in Shaker Heights where Kinsman (now Chagrin Boulevard), Warrensville Center, and Northfield Roads come together. The photograph shows one traffic light regulating the flow of traffic. Today it takes 20 sets of lights to do what this one did in 1935. (CSU.)

MORELAND COURTS. In 1922, a local entrepreneur, Josiah Kirby, planned a luxury apartment complex around Moreland Circle, a rapid transit junction. The idea was to include offices and shopping in addition to upscale apartments designed with an Old English theme. The plan received approval from the Van Sweringen brothers, and construction began on the first apartment unit located on Shaker Boulevard, west of Moreland Circle. (CSU.)

WIDENING NORTH MORELAND BOULEVARD. The luxury apartment project came to an abrupt halt when Josiah Kirby went bankrupt. The project was dormant for five years until the Van Sweringens took it over, resuming construction on the apartment buildings—Moreland Courts—planning a new shopping area around Moreland Circle, and reconfiguring its roads. (CSU.)

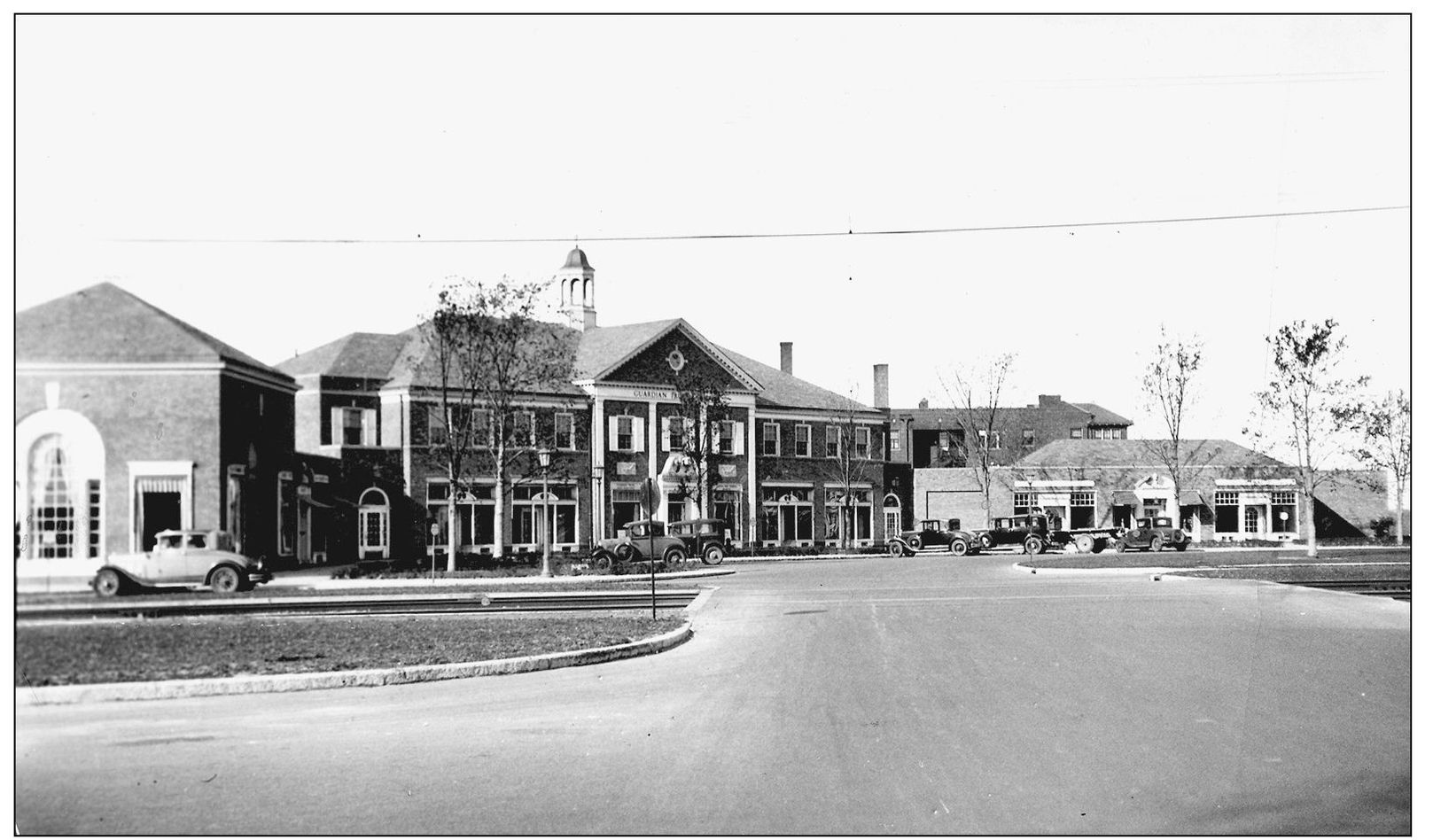

SHAKER SQUARE. Most of this development was within the boundaries of Shaker Heights, then restricted to residential use. The Van Sweringens returned a section of Shaker Heights to the City of Cleveland and created Shaker Square as a commercial district, one of the first shopping centers in the nation. (SHPL.)

SHAKER SQUARE, 1929. To create this shopping district, Moreland Circle was “squared,” becoming a New England–style town green with four quadrants of shops designed with Georgian-style architecture. The Shaker Heights Rapid Transit ran through it, providing a link both to downtown Cleveland and the eastern suburbs. O. P. Van Sweringen took particular interest in this project, turning to it for a break from the demands of his other businesses. (CSU.)

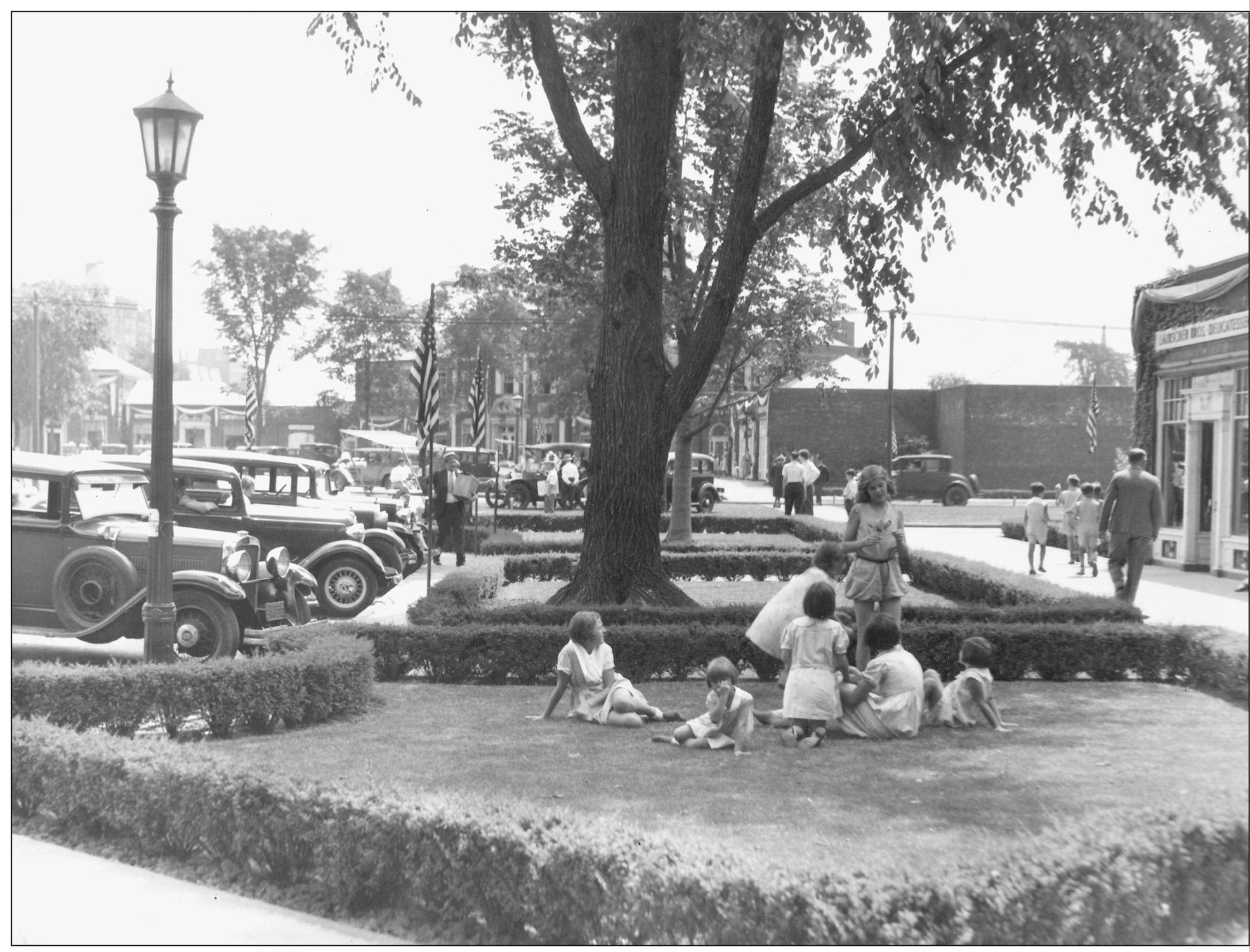

LOUNGING AT SHAKER SQUARE. The ideals of the garden city movement also found their way into the design of Shaker Square, which features considerably more green space than modern shopping centers. It was laid out not just for selling merchandise but for providing a place of relaxation and renewal. Here a group of children stretch out over the carefully manicured lawn in 1933. (CSU.)

SEDGEWICK ROAD, 1923. Deep front yards, extensive landscaping, traditional styles, detailing, a feeling of comfort and hospitality—these characterized the Shaker Heights home. Each was required to be two stories, placed at a uniform distance from the street, and set apart from others to allow light to enter from all sides. A house should not stand out from its neighbors and call attention to itself; each should fit within the context of its neighborhood. There was diversity in Shaker Heights housing, but this was carefully planned diversity. Uniform lot sizes for each street helped insure a consistent appearance with smaller lots in some sections of the city to provide housing for those of different income levels. These houses on Sedgewick Road have frontages of 100 feet each. Less expensive homes could be found on streets featuring frontages of 75, 60, 50, or 40 feet. Yet throughout Shaker Heights, the architectural and building standards were maintained. A cheaper house did not mean shoddy construction, and architectural standards were the same throughout the community. (SHPL.)