Seven

REINVENTING SHAKER HEIGHTS

Despite pledges that Shaker Heights would remain the same forever, change did come. The housing stock, solid though it was, began to age. Proximity to the city raised fears of crime. And a new generation of people who could afford to live in Shaker Heights were African Americans.

In 1925, a black physician and his family moved to Shaker Heights. Shots were fired at the house and the garage torched. Police assigned for protection harassed the family, searching them as they entered and left their home, and the family ultimately left. Residents formed the Shaker Heights Protective Association, which drew upon the country club analogy to claim that neighbors have a right to determine who can join the neighborhood. While race was not mentioned, many have argued that the purpose was to keep out those who did not “fit,” especially African Americans.

In 1954, a bomb exploded at a home under construction for a prominent black attorney. Neighbors rallied again, but this time their purpose was different. Instead of devising plans to keep people out, this group—the Ludlow Community Association—started a process of working together to establish a stable diverse community.

Another challenge to the community appeared in 1964 when the Cuyahoga County Highway Department announced that two freeways would cut through Shaker Heights. Fearing the effects, citizens banded together to oppose the freeways and, surprisingly, they won. The Nature Center at Shaker Lakes was established, insuring that no super highways would ever be built in that area.

In 1970, the Shaker Heights city schools addressed the increasing diversity of its student body by creating the Shaker Schools Plan, a voluntary busing program that promoted integration. In 1987, the school board followed up by reorganizing elementary schools for racial balance. Plans developed in Shaker Heights schools have been followed throughout the nation as a model for providing excellent education while serving a diverse student body.

The result is a reinvented Shaker Heights. It is still a planned community, but the goals have changed, and today the city has been able to realize an elusive dream: a stable diverse community.

WHITE SHAKER HEIGHTS. A 1938 book produced by the board of education displays 126 pages of photographs depicting life in the Shaker Heights schools. The students are shown benefiting from an innovative approach to education in which substantial resources were available to them. No people of color appear on those pages. (SHCS.)

MALVERN SCHOOL, 1930S. Shaker Heights sought to establish continuity with the North Union Shakers, but in this regard there was a difference: the Shakers featured more diversity than Shaker Heights. Among North Union residents were Native Americans, an ex-slave, a German Jew, and a Swiss ex-priest. The Shakers welcomed all seekers of truth; Shaker Heights would have to work on that one. (SHCS.)

PROGRAM PROMOTING INTEGRATION. Restrictions on Shaker Heights deeds had put controls on who could buy property in the city, but such covenants throughout the nation were ended by decision of the United States Supreme Court in 1948. Already, though, Shaker Heights was changing. African American families had purchased houses in western sections of Shaker Heights, and new apartment buildings increased the economic and racial diversity of residents. White flight threatened. (SHPL.)

KINSMAN BECOMES CHAGRIN. This hand-lettered sign announces a name change from Kinsman Road to Chagrin Boulevard. Kinsman was an early route in the area running from Cleveland to Kinsman, Ohio. A series of violent incidents on Kinsman in Cleveland inspired Shaker Heights, in 1959, to change the name of its section to Chagrin Boulevard as Shaker Heights sought to distance itself from Cleveland’s problems. (SHPL.)

SHAKER HEIGHTS PROTECTIVE ASSOCIATION. In 1925, 400 prominent residents formed the Shaker Heights Protective Association after a black family attempted to make a home in Shaker Heights. This association warned that “undesirable” neighbors could move into the city if “restrictions” were not put into place. While race was not explicitly mentioned, such restrictive covenants were used nationwide to keep minorities out of communities. (SHPL.)

LUDLOW COMMUNITY ASSOCIATION. The response to a bombing directed against an African American family in the 1950s was different. Neighbors came together first to help the family clean up the damage, and then blacks and whites began a dialogue. These conversations coalesced into a desire to maintain the Ludlow neighborhood as an environment where white and black families could live together in a shared community. (SHPL.)

LUDLOW NEIGHBORHOOD. The Ludlow Community Association—formed as a result of these conversations—embarked upon an innovative plan to maintain the quality and diversity of the Ludlow neighborhood. One program encouraged white buyers to move into Ludlow and offered loans for that purpose while also encouraging black families to move into areas of Shaker Heights in which mostly white families lived. (SHPL.)

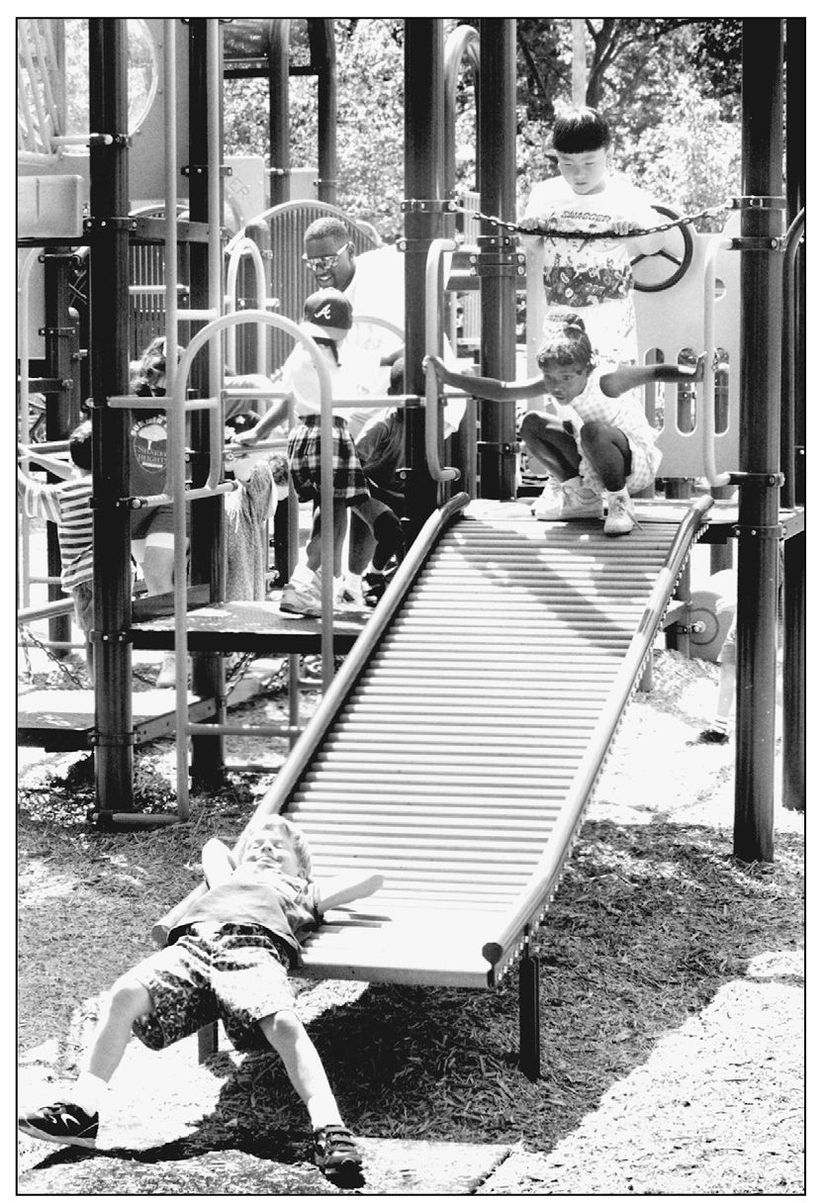

NEIGHBORHOOD PLAYGROUND. Building upon a long-standing Shaker Heights value, residents realized that an integrated city does not just happen; it takes planning. In 1967, the Shaker Housing Office was formed and began a loan program—as well as a national advertising campaign—aimed at promoting diversity throughout the city. (SHPL.)

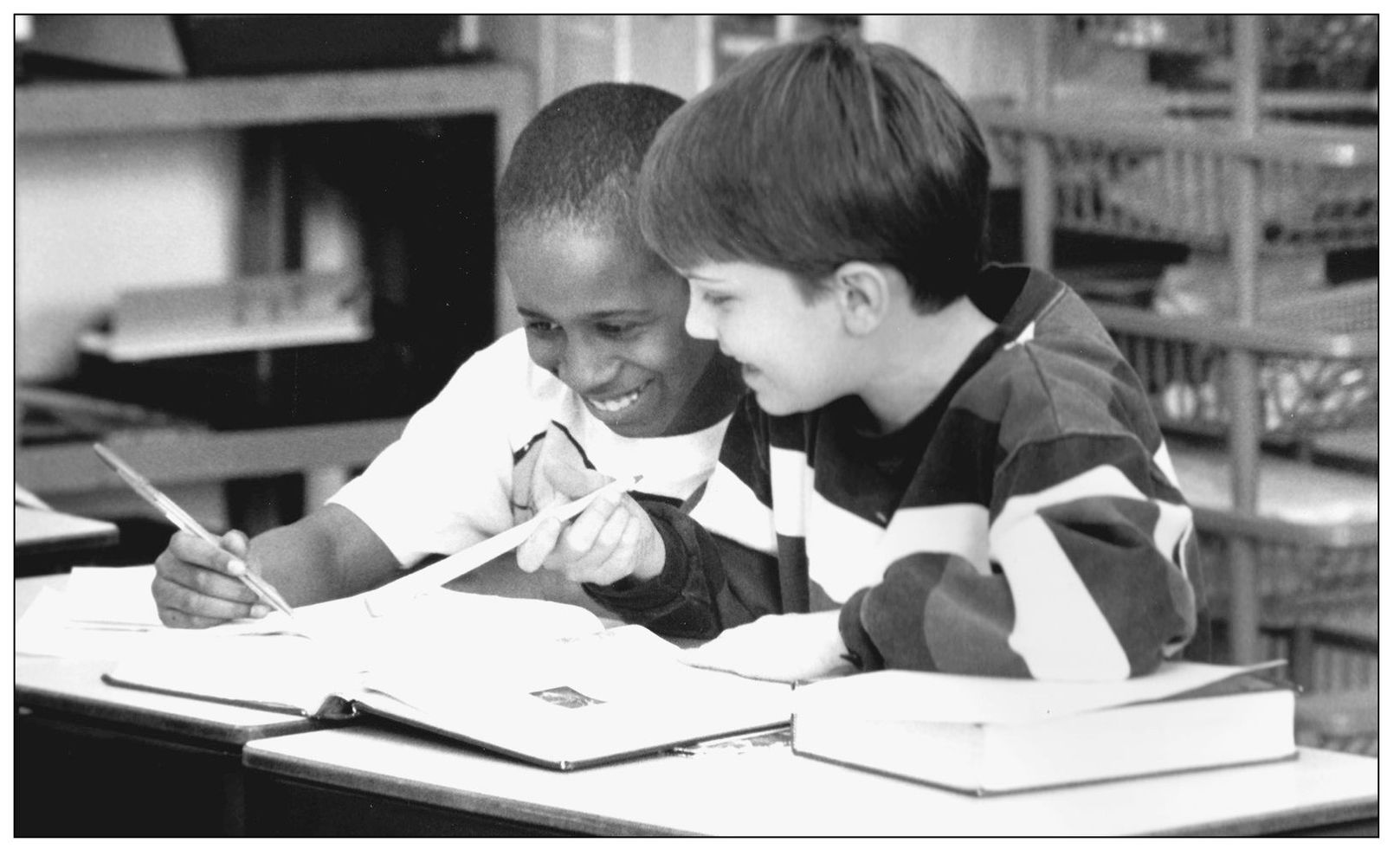

STUDENTS READING. The schools faced similar challenges. As minority families moved into areas served by Shaker Heights city schools, elementary schools were becoming segregated. In 1970, the board of education adopted the Shaker Schools Plan, a voluntary busing program that promoted integration. In 1987, the board of education reorganized the elementary schools for racial balance. Both plans have been models for school districts nationwide. (SHPL.)

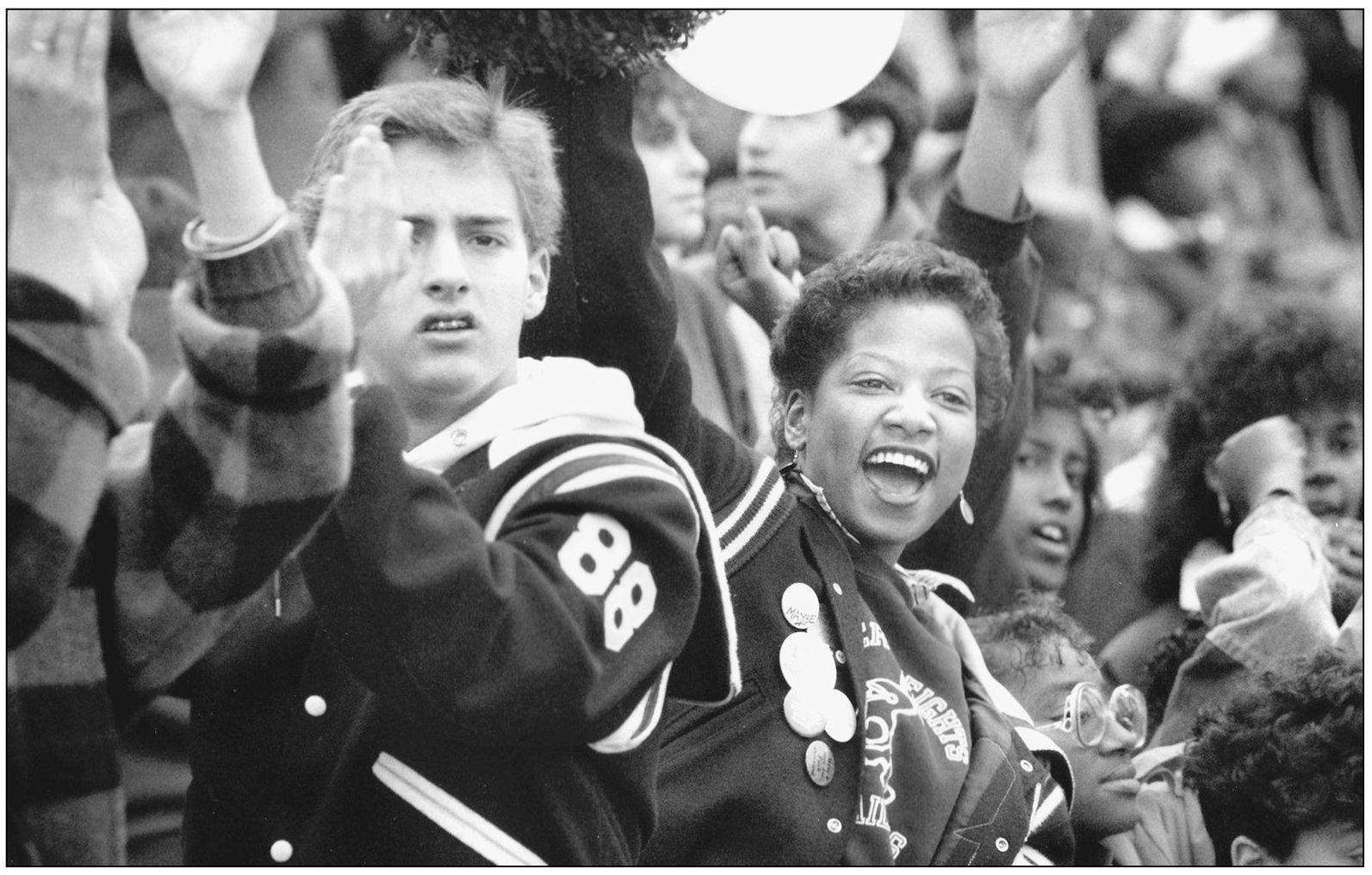

PLAYING TOGETHER. The result has been another benefit for students in Shaker Heights schools. Not only do they receive a high-quality education based on innovative approaches to learning, they also share this experience in a diverse student body. Shaker Heights schools offer an environment in which young people become familiar with life in a multiracial and multicultural community. (SHPL.)

WORKING TOGETHER. Friendships among students in elementary school that crossed the color lines often did not survive into middle school and high school. In response, students formed an organization to help maintain healthy relationships within a diverse student body. Called the Student Group on Race Relations, about 250 volunteers present programs to fourth and sixth graders each year that help create and sustain healthy relationships among people of different races. (SHPL.)

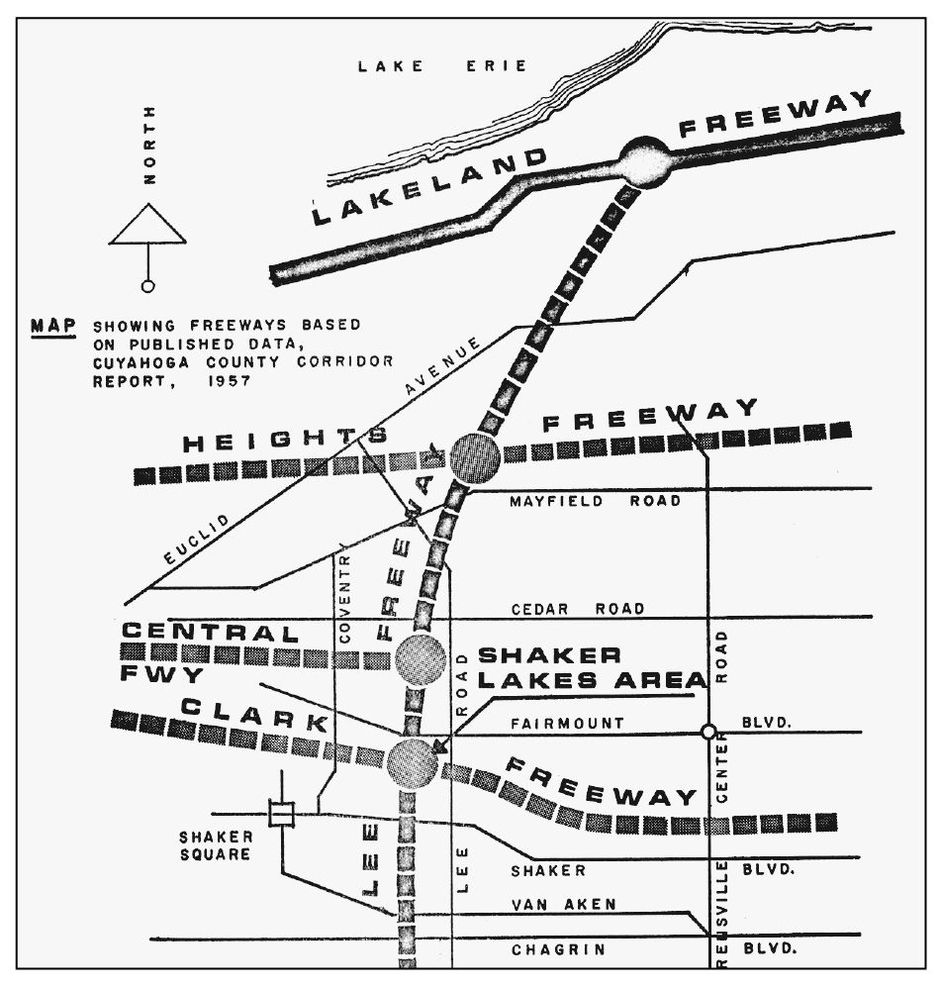

CLARK AND LEE FREEWAY ROUTES. Another potentially convulsive change for Shaker Heights was initiated by the Cuyahoga County Highway Department in 1964 when it announced plans to build two eight-lane freeways through the city. An estimated 100,000 vehicles would use these roads daily. At the time, highways were an easy sell with most communities eager to get them. Not Shaker Heights. (NCSL.)

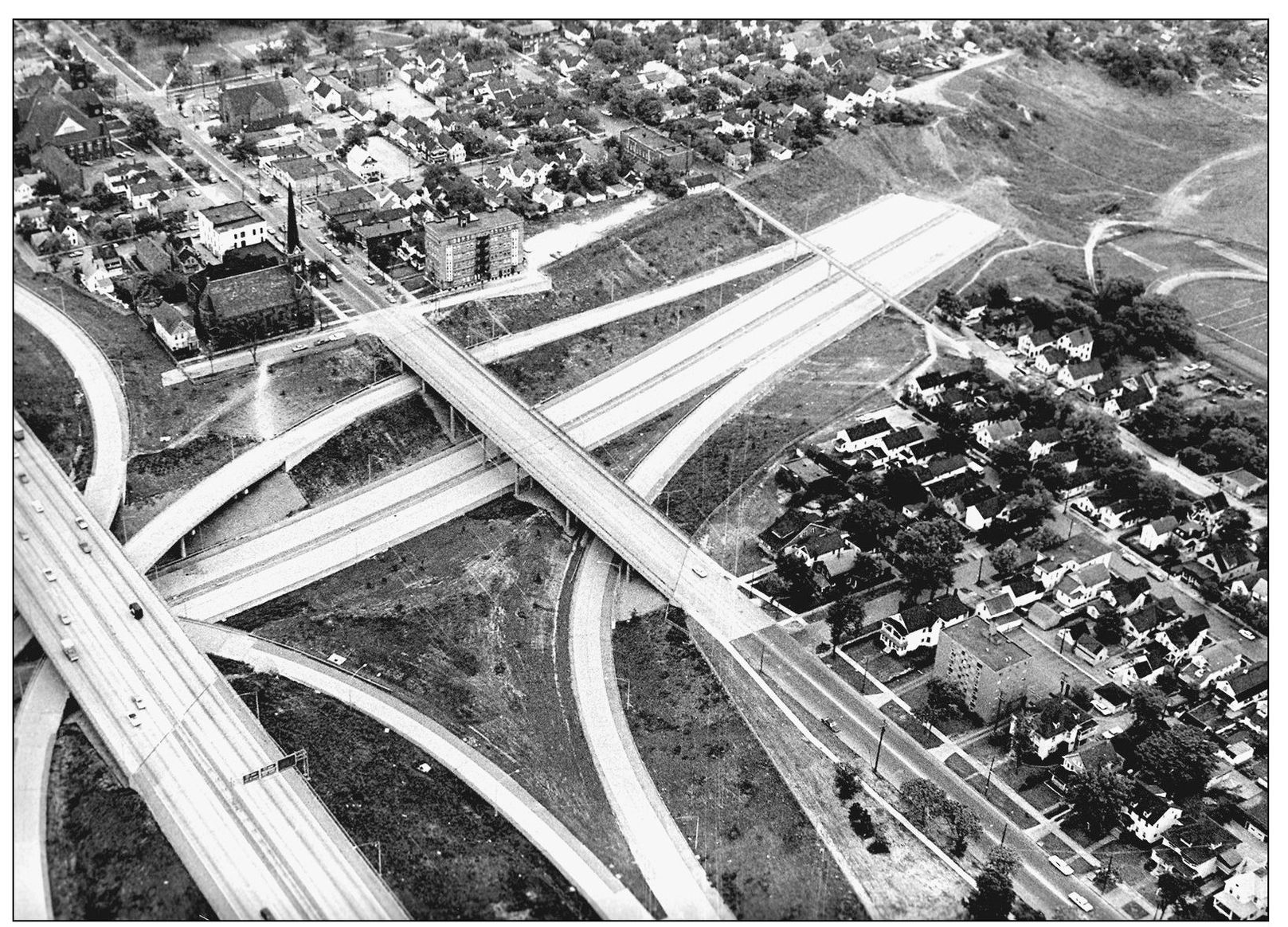

START OF CONSTRUCTION, CLARK FREEWAY. The freeways seemed inevitable. Money had been allocated, construction had begun, and, besides, freeways represented progress. The highway department sought to mollify residents with assertions that freeways increased the value of adjacent properties, had no appreciable effect upon noise or pollution levels, and made life easier for everybody. The start of the Clark Freeway at Interstate 71 is pictured here. (CSU.)

CITIZEN ACTION AGAINST THE FREEWAYS. Community groups united to fight the freeways, including the Shaker Historical Society, the Audubon Society, and a coalition of 33 garden clubs. They mounted a campaign of intense pressure on elected officials to stop the freeways. During a snowstorm in January 1970, opponents came out in force to state their case. The following month, the governor announced that the freeways would not be built. (SHS.)

NATURE CENTER TRUMPS A FREEWAY. Ironically, the early Shakers played a role in deciding this controversy. Over a century earlier, they had created two lakes by damming Doan Brook. Developers retained the lakes and donated them to the Cleveland Park Commission. In 1968, a new federal law prohibited building freeways in public parks. The Nature Center at Shaker Lakes was established as a resource for conservation and education. (NCSL.)

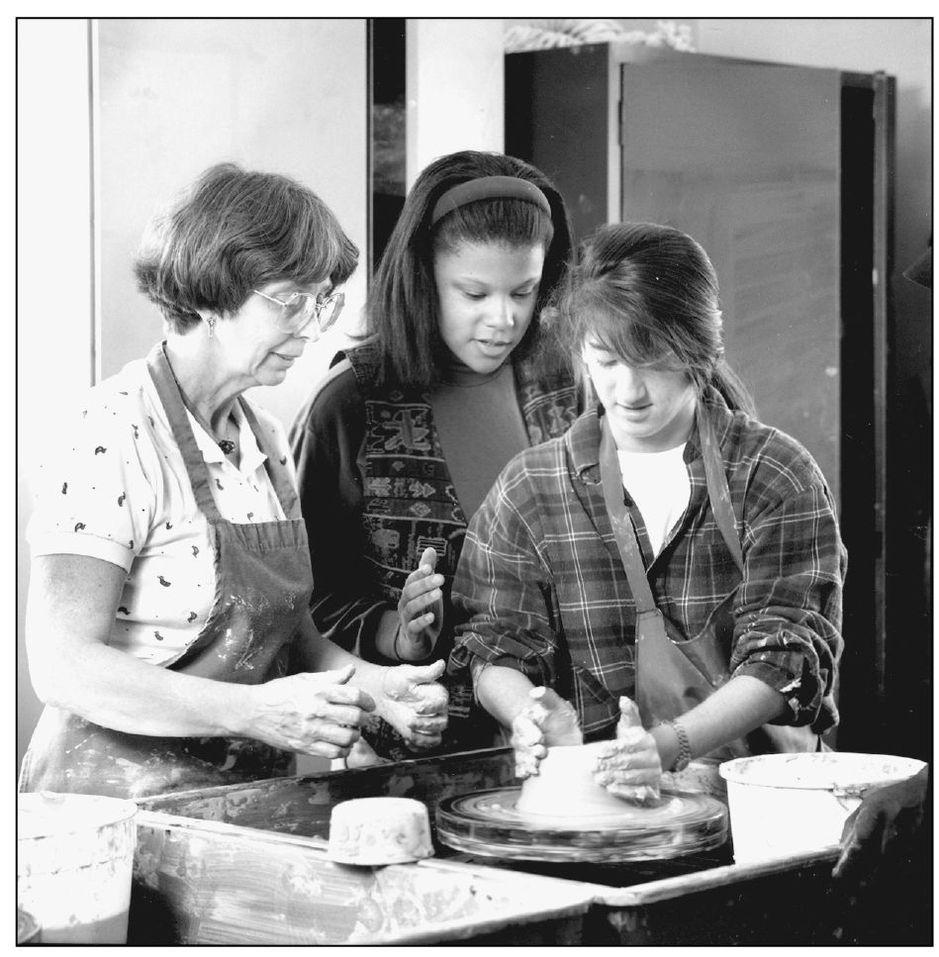

MAKING POTTERY. Beginning with the North Union settlement, residents of this community have sought to build an ideal society. The Shakers created a way of living they believed God had established for those of the most developed spirituality. The Van Sweringens’ Shaker Heights continued utopian themes offering residents a life of harmony and serenity, not in a cooperative community but in a city of exclusive homes and gardens. (SHPL.)

GREGORY PENNINGTON PAINTS THE BEATLES. Today’s Shaker Heights has again reinterpreted the utopian model. Now the ideal community includes people of different races and cultures living with mutual respect and affirmation. In such a community, each has opportunities to develop his or her own talents, such as in this photograph of a participant in an arts enrichment program sponsored by the Shaker Heights city schools. (SHPL.)

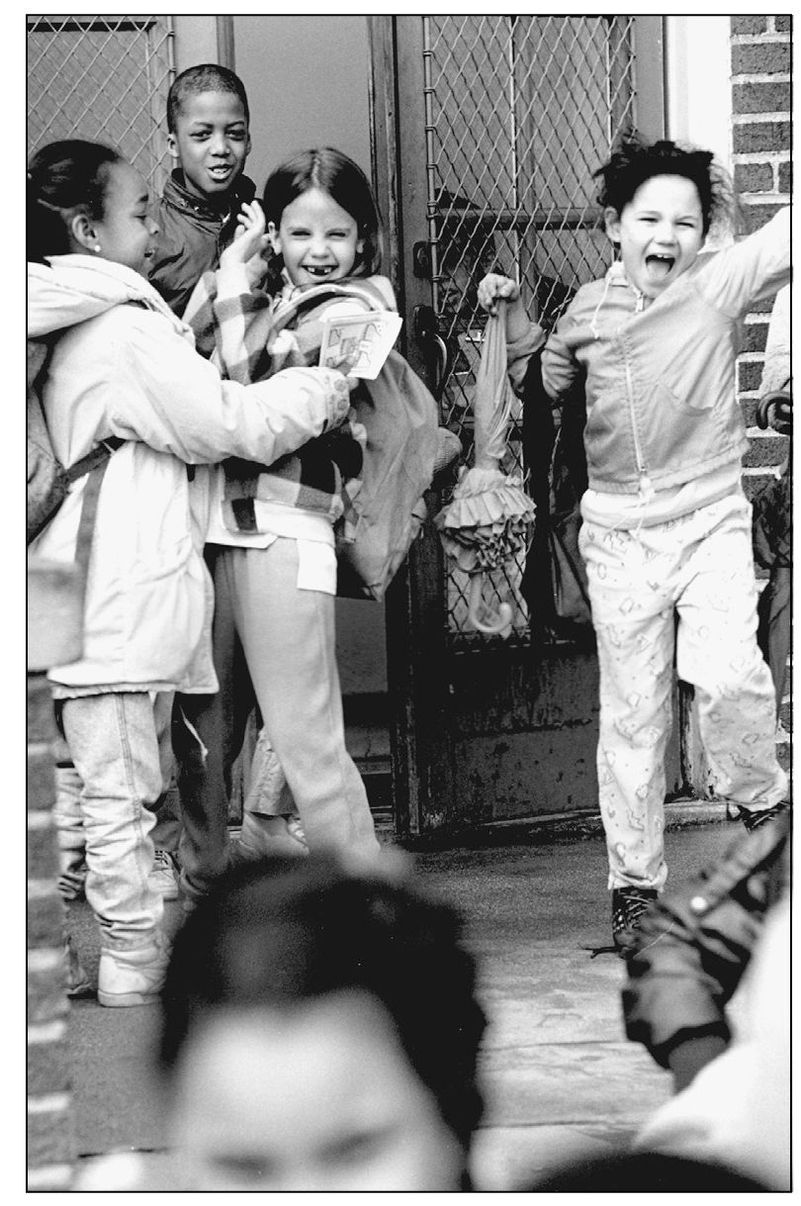

SHAKER HEIGHTS CHILDREN. The vision of what an ideal community should be has changed from generation to generation, but the methods of achieving it are similar. Central to the Shaker and the Shaker Heights method is intense planning aimed at creating an environment that will bring out the best in its residents. As the Van Sweringen Company put it, “Most communities just happen; the best are planned.” (SHPL.)

MEMBERS OF THE BAND. Another quality that extends throughout the generations is a sense of distinctiveness, that something unique and important happens here. “We had been part of a unique experiment in integration,” said one person who grew up in the Ludlow neighborhood. The tradition of “unique experiments” is long-standing in this community. (SHPL.)

PLEDGE OF ALLEGIANCE. Perhaps what Shaker Heights offers—in addition to its housing and green space and schools—is something to believe in. It is the dream of a vital community that extends back to the Shakers, a dream that is never fully realized but that does occur in moments of everyday life when human connections are made. (SHPL.)

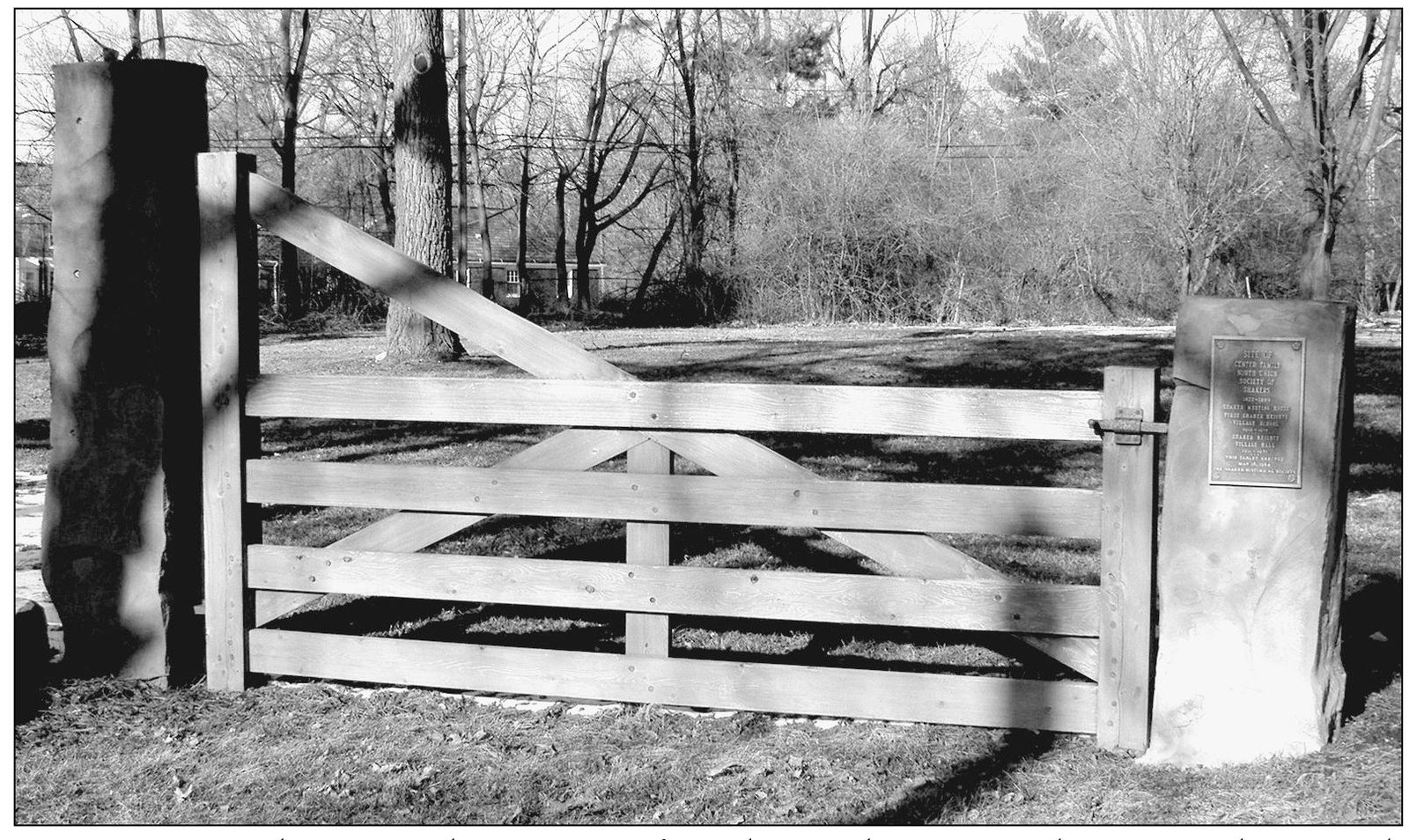

SHAKER GATE. This gate with stone posts from the North Union settlement stands in a park at the northeast corner of Lee Road and Shaker Boulevard. The Shaker meetinghouse once occupied this site, then the Van Sweringen Company’s offices, which they shared with the village offices and schools. Today this Shaker gate stands as a reminder of the generations who have contributed to the community of Shaker Heights.